-ћетки

-–убрики

- ј–“»Ќџ –ќ——≈““» (16)

- ѕ–ќ«≈–ѕ»Ќј PROSERPINA (3)

- BEATA BEATRIX (2)

- LADY LILITH@SYBILLA (2)

- ѕи€ де “оломеи (1)

- BOCCA BACIATA (1)

- «≈Ћ®Ќџ≈ –” ј¬ј (1)

- REGINA CORDIUM QUEENG of HEARTS (1)

- THE BLESSED DAMOSEL Ѕлагословенна€. (1)

- ASPECTA MEDUSA (1)

- ƒама в окне. The Lady of the Window. (1)

- ¬идение ‘иаметты. Vision of Fiammetta. (1)

- ƒневна€ мечта. The Day Dream и The Bower Meadow (1)

- „ј—“» “≈Ћј. THE BODY PARTS. (13)

- Ќј√ќ“ј ¬ »— ”——“¬≈ (5)

- ќЋЋ≈ ÷»я ‘≈“»Ў»—“ј (4)

- —“ќѕџ » »—“» скованные одной цепью. (3)

- ќЌ –≈“Ќџ≈ Ќќ∆ ». (1)

- ћќƒ≈Ћ» –ќ——≈““» (11)

- ƒ∆≈…Ќ ћќ––»— Ѕ®–ƒ≈Ќ JANE MORRIS BURDEN (4)

- ‘анни орнфорт (2)

- јЌЌ» ћ»ЋЋ≈– ANNIE MILLER (1)

- јЋ≈ —ј ¬ј…Ћƒ»Ќ√ ALEXA WILDING (1)

- ЅјЋ≈“ — “–≈“№≈√ќ я–”—ј. (9)

- HANNIBAL LECTER (5)

- ристина –оссетти (5)

- ристина –оссетти Christina Rossetti поэзи€ poems (3)

- ART DECO (4)

- √јЋ≈–≈я Ћ≈ћѕ»÷ ќ… (1)

- “јћј–ј Ћ≈ћѕ»÷ ј (1)

- „“ќ ¬ »ћ≈Ќ» “≈Ѕ≈ ћќ®ћ? (4)

- Ёлизабет —иддал (4)

- ∆»«Ќ№ ј–“»Ќ. (3)

- мо€ живопись. My paintings. (3)

- ѕќЁ«»я (1)

- јльфред “еннисон (1)

- —ѕ»—ќ ’”ƒќ∆Ќ» ќ¬ (1)

- ‘–»Ќј —≈ћ»–јƒ— ќ√ќ (1)

- Ќ»√ј ќ –ќ——≈““» (1)

- ћјЌ№≈–»«ћ (1)

- —писок работ –оссетти. The full list of Rossetti's (1)

- DOUBLE WORKS (1)

- јЌќЌ—џ –”Ѕ–» (2)

- ѕ–≈–ј‘јЁЋ»“џ (38)

- ¬—≈ ѕ–≈–ј‘јЁЋ»“џ (11)

- —ѕ–ј¬ » по ѕ–≈–ј‘јЁЋ»“јћ (4)

- ѕ–≈ƒ“≈„» (3)

- ѕ–≈–ј‘јЁЋ»“џ ¬ –ќ——»» (1)

- –ќ——≈““». ROSSETTI. (50)

- –ќ——≈““» ∆»«Ќ№ ROSSETTI LIFE (43)

- ƒжон ”иль€м ѕолидори и его ¬ампир (1)

- –ќ——≈““» —ќ —“ќ–ќЌџ (1)

- пќЁ«»я –ќ——≈““» (1)

- ћ”«≈» —ј…“џ. MUSEUMS. SITES. (15)

- ћ≈“–ќѕќЋ»“≈Ќ (3)

- ’”ƒќ∆≈—“¬≈ЌЌџ… ћ”«≈… ƒ≈Ћј¬ј–ј. (3)

- ћќ… Ё–ћ»“ј∆ (3)

- Ћ»¬Ћ≈Ќƒ— »… ћ”«≈… (1)

- ћќ» –ќћјЌџ (58)

- »— ј“≈Ћ№ 2 (41)

- роман "”читель" (9)

- ј« ≈—ћ№ (3)

- Ё «»—“≈Ќ÷»я (1)

- Novels, English versions. (1)

- мои стихи (1)

- ј—‘јЋ№“ (1)

-ћузыка

- гуд бай дарлинг

- —лушали: 169 омментарии: 0

- полный закат

- —лушали: 188 омментарии: 1

-ѕоиск по дневнику

-ѕодписка по e-mail

-»нтересы

-—ообщества

-—татистика

«аписи с меткой данте габриэль россетти

(и еще 185 запис€м на сайте сопоставлена така€ метка)

ƒругие метки пользовател€ ↓

an english autumn afternoon annie miller aspecta medusa beata beatrix burne-jones carlisle wall christina georgina rossetti christina rossetti dante gabriel rossetti eleanor fortescue-brickdale eugene onegin fanny co feet fetish frank cadogan cowper gabriel charls dante rossetti gg augustus leopold girls goblin market hannibal lecter john everett millais kelmscort manor la girlandata la pia de' tolomei lady lawrence lempica madox brown mariana mary magdalene at the door of simon the pharisee may morris naked nude regent street rossetti sancta lilias simeon solomon sing song a nursery rhyme book stacy marks the damsel of the sanct grael the music master vampyre william holman hunt william michael rossetti willian allinham working men's college артур хьюз балет бесплатно блаженна€ беатриче бойс галере€ тейт гамлет и офели€ генри треффри дун голубь грант вуд данте данте габриэль россетти джейн моррис джейн моррис бЄрден живопись животные искатель искусство кларк кристина россетти лемпицка€ мариинский мари€ магдалина у дверей симона-фарисе€ менады нагота новый роман ножки поэзи€. christina rossetti poems прерафаэлиты прозерпина рисующий ангела роман россетти сиддал символизм скачать сомова соцреализм то́мас карле́йль уотерхауз фанни корнфорт хант хьюз чаадаев эпиграф

–ќ——≈““» 1871 - 74 |

ƒневник |

–ќ——≈““» 1873

«–ождественска€ песнь» — картина , созданна€ в 1874 году.

–анее (в 1857—58 годах) –оссетти уже создал работу с таким же названием, но в иной технике и композиции. Ќатурщицей дл€ картины стала не столь часто по€вл€вша€с€ на его работах Ёллен —мит. –оссетти увидел —мит на „елси стрит в 1863 году. расота Ёллен отличалась от привычных натурщиц с работ –оссетти, хот€ еЄ округлые черты лица и полные губы имели некоторое сходство с ‘анни орнфорт, красота которой, по мнению –оссетти, к тому времени начала ув€дать. ¬ отличие от ƒжейн ћоррис, јлексы ”айлдинг и –ут √ерберт, обладавшими острыми и характерными чертами лица и позировавших дл€ типажей роковых женщин, Ёллен —мит обладала более м€гкими и чувственными чертами лица.

јссистент –оссетти √енри “реффри ƒанн описывал эту картину как «ƒевушка в блест€щей восточной одежде малинового цвета с узором из золотой нитей, играюща€ на струнном инструменте и поюща€ Hodie Jesu Christus natus est Hallelujah». —трока из песни о рождении ’риста начертана на раме картины. —троки вз€ты из одной из кол€док, которые –оссетти собирал, записывал и переводил со среднеанглийского €зыка.

«–ождественска€ песнь» одна из серии женских портретов с музыкальными инструментами и схожей композицией (женщины изображены по по€с и в объЄмных одеждах); за ней далее последовали музыкальные портреты «La Mandolinata», «La Ghirlandata» «¬ероника ¬еронезе», «ћорские чары» и другие. —в€зь женской красоты, музыки и экзотической одежды и деталей декора была одной из отличительных черт нового художественного стил€ Ѕритании 1860-х и 1870-х годов, в котором сочетались элементы эпохи ¬озрождени€, восточного искусства и классики. ÷ентральным образом на полотнах художников стала женщина-музыкант, отрешЄнна€ задумчивости и своей игре; при этом сама музыка может быть как романтичной, так и трагичной (как на портрете –оссетти «–имска€ вдова»); художник стремилс€ создать своей работой настроение, вызванное неслышимой музыкой. ¬осточна€ мандолина с двум€ струнами принадлежала самому –оссетти; этот инструмент уже по€вл€лс€ на его других произведени€х. ѕлатье Ёллен —мит уже по€вл€лось на ней же на картине –оссетти «¬озлюбленна€».

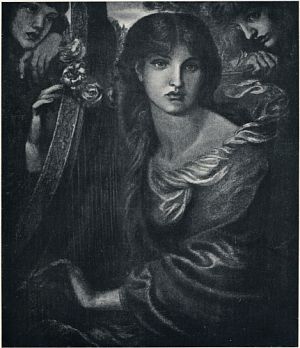

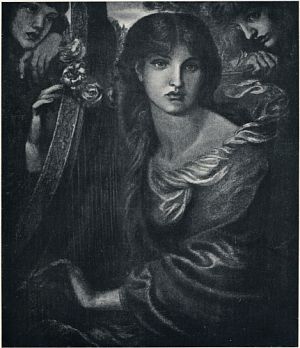

La Girlandata 1873.

WMR's early commentary on the picture is much to the point: “The name La Ghirlandata may be translated ‘The Garlanded Lady,’ or ‘The Lady of the Wreath.’ The personage is represented singing, as she plays on a musical instrument; two youthful angels listen. The flowers which are prominent in the picture were intended by my brother for the poisonous monkshood: I believe he made a mistake, and depicted larkspur instead. I never heard him explain the underlying significance of this picture: I suppose he purposed to indicate, more or less, youth, beauty, and the faculty for art worthy of a celestial audience, all shadowed by mortal doom” ( WMR, DGR: Designer and Writer, 86-87 ). But it seems quite clear that the picture is also a (so to speak) Venetian rendering of Keats's singing and garlanded “Belle Dame Sans Merci”. The picture thus connects back to some of DGR's earliest work, such as the drawing of La Belle Dame Sans Merci as well as to several of the late, ominous pictures, like Ligeia Siren.

DGR was working on the picture in early July 1873, and by the middle of the month it had been paid for by William Graham (£840) and was, DGR told Charles Howell, “well advanced”. On August 23 he wrote to Watts-Dunton that “I have now nearly finished [a picture] I call La Ghirlandata. It contains three heads—a lady playing on a harp and two angels listening—and an infinity of other material—and in brilliancy is more like the Beloved than any other picture of mine you have seen. It belongs to Graham, who wants it in Scotland, but perhaps I may send it for a few days to London to show to a few”. He described the picture to Treffry Dunn in these terms: “The one I am doing for him now is not B[lesse]d Dam[oze]l but that figure playing on the queer old harp which I drew from Miss W[ilding] when you were here with her. The two heads of little May are at the top of the picture. It will really be a successful thing I am sure now, and is getting fast towards completion, but I have not yet got the frame. It ought to put Graham in a good humour and I am glad he is to have it as he is the only buyer I have who is worth a damn.” And to William Bell Scott he wrote even more enthusiastically: “For some six weeks past I have been at work solely on a picture now just finished and called La Ghirlandata—about 4 feet by 3. It is a woman playing on a sort of solid harp I have—an instrument stringed on both sides and very paintable in form. Behind her two angels lean through foliage and listen, and there is an immensity of work in the picture which is quite full of flowers and leaves all most carefully done from nature. It is the greenest picture in the world I believe—the principal figure being dressed in green and completely surrounded with glowing green foliage. I believe it is my very best picture—no inch of it worse than another.”

Ёта картина принадлежит к группе декоративных полотен, изображающих женщин, играющих на музыкальных инструментах. — 1871 по 1874 годы –оссетти создал четыре картины этой тематики, кроме La Girlandata это Veronica Veronese, The Bower Meadow и Roman Widow.

¬иль€м ћайкл –оссетти, комментиру€ картину, утверждал, что название можно перевести как Ћеди, увенчанна€ гирл€ндой или венком. дама играет на музыкальном инструменте и поЄт, а два юных ангела слушают. –оссетти задумал, что цветы на переднем плане картины - €довитый аконит, но ошибс€ и изобразил жимолость.

–оссетти описыва€ картину, как "самую зелЄную картину в мире". ѕриходит на ум "таможенник –уссо" с его джунгл€ми и тридцатью оттенками зелЄного.

ƒанте –оссетти никогда не объ€сн€л смысл картины, но ћайкл –оссетти предполагал, что он просто хотел изобразить молодость, красоту и искусство, достойное внимани€ свыше. » над всем этим тень судьбы всех смертных. —овершенно очевидно, что картина €вл€етс€ "венецианской" переработкой поющей и украшенной гирл€ндой “Belle Dame Sans Merci” итса. артина имеет €вную св€зь с ранними работами –оссети, такими как “La Belle Dame Sans Merci”. и с некоторыми поздними зловещими картинами, такими как Ligeia Siren. –оссетти начал работу над картиной в начале июл€, а в середине мес€ца получил аванс 840 фунтов от William Graham . ѕо поводу чего написал „арльзу Charles Howell "неплохо авансирован". 23 августа он написал Watts-Dunton, что почти закончил картину, которую назвал La Girlandata. " Ќа ней три головы - дама играюща€ на арфе, и два слушающих ангела, а также бесконечное количество других деталей. »з виденных тобой моих картин она по €ркости больше всего похожа на ¬озлюбленную. ќна принадлежит Graham, который хочет получить еЄ в Ўотландии, но, возможно, € пошлю еЄ на несколько дней в Ћондон, показать кое-кому.Treffry Dunn он описывал картину так: та, что € пишу сейчас, это не Blessed Damsel, это дама, играюща€ на странной старомодной арфе, которую € рисовал у Miss W[ilding] ,когда ¬ы также были у неЄ. ¬ верхней части картины две головки юной ћэй. артина быстро двигаетс€ к завершению и € уверен, что она будет успешной. Ќо € ещЄ не получил раму. я считаю, что Graham будет доволен и рад,что именно он получит картину, так как это мой единственный сто€щий покупатель. William Bell Scott он писал с ещЄ большим энтузиазмом: "ќколо шести недель € работаю над картиной, которую почти закончил и назвал La Girlandata - 4 на 3 фута.

»зображающую женщину, играющую на старинной арфе со струнами с обеих сторон и очень живописную по форме. —зади два ангела склон€ютс€ сквозь листву и слушают". Ќад картиной пришлось поработать, так как много цветов и листьев тщательно изображенных с натуры. Ёто сама€ зелЄна€ картина в мире - главна€ фигура одета в зелЄное и полностью окружена €рко зелЄной листвой. я считаю эту картиной моей лучшей, во вс€ком случае ничуть не хуже других. јрфа украшена белыми крыль€ми - символом пролетающего стремительно времени, а гирл€нда, давша€ название картине, состоит из роз и медуницы - символов сексуальности дл€ –оссетти.

јлекса ¬айлдинг позировала дл€ музицирующей женщины, а ћэй ћоррис дл€ ангелов.

May Morris 1872

May Morris 1872

May Morris 1871

Model: May Morris. Younger daughter of William and Jane Morris (b. 1862).

Medium: Probably chalk. Surtees says oil or watercolor, but in a letter DGR describes a chalk drawing of May Morris.

Jenny Morris 1871.

Jenny Morris 1871.

«абавные картинки, не скажешь, что девочкам 9 и 10 лет соответственно. » всЄ –оссетти на мамку сбиваетс€.

Roman Widow

When Frederick Stephens was preparing his article on DGR's new works for The Athenaeum, eventually published on August 14, 1875, DGR supplied him with this commentary: “Dîs Manibus. The title here suggests the subject—that of a Roman widow seated in the funeral vault beside her husband's cinerary urn, the inscription on which is headed with the invariable words as given above; and playing on two harps (as seen in some classical examples) an elegy ‘to the Divine Manes.’ She is robed in white—the mourning of noble ladies in Rome. The antique form of the harps is rendered in tortoiseshell chiefly with fittings of ebony or dark horn embossed in silver. The harp on which her right hand plays is wound with wild roses; and beneath the urn, across the wall of green marble, is a large festoon of garden roses, repeating as it were the festoon to be almost universally found on such urns and which this one displays round its inscription. About the urn is wound the widow's wedding-girdle of silver, dedicated to the dead as to the living husband. The moment chosen must be supposed to belong to those special occasions on which the Romans solemnized mortuary rites, and which recurred at intervals during the year” ( Fredeman, Correspondence, 75.93 ).

The painting is particularly important because of a set of strange and suggestive relationships that it has with other works by DGR that date from 1872-1877, especially Veronica Veronese, La Ghirlandata, and A Sea Spell. These four pictures share a number of features, motivic and compositional, even as their titles and nominal conceptions are very different. Considered together, they exhibit as it were four facets or aspects of a single iconic figure of highly ambiguous import.

For The Roman Widow in particular, DGR's own title—Dis Manibus—connects it to his trenchant epigram on Flaubert, written in 1880 after DGR had read of Flaubert's death. Titled by DGR “Dis Manibus”, the epigram draws a parallel between the decadence of Nero's Rome and the decadence of the Second Empire. DGR's treatment of all these materials draws his work into the same dark vortex, a fact underscored in the epigram, where the dying words of two Roman emperors, Vitellius and Nero, represent an antithesis of the glorious and the dreadful.

All of these pictures focus on a musical icon that traditionally represents an ideal order aesthetically pursued. Pater's famous pronouncement in “The School of Giorgione”, that “all art aspires to the condition of music”, is certainly being represented here. But in DGR's case the music—and therefore the practice of art—bears as well terrible meanings that Pater's work does not bring forward in this way.DGR began the picture around October 1873, as his letter to Leyland of October 4, describing the plan of the work indicates: “This I have cartooned from nature and am now beginning to paint it. It is called Dis Manibus—the dedicatory inscription to the Manes, the initials of which (D. M.) we find heading the epitaphs in Roman cinerary urns. In the picture, a lady sits in the ‘Columbarium’ beside her husband's urn which stands in a niche in the wall, wreathed about with roses and having her silver marriage-girdle hanging among them. Her dress is white—the mourning of nobles in Rome—and as she sits she plays on two harps (one in her arm and one lying beside her) her elegy addressed ‘Dis Manibus.’ The white marble background and urn, the white drapery and white roses will combine I trust to a lovely effect, and the expression will I believe be as beautiful and elevated as any I have attempted. Do you like me to consider this picture as yours at 800 guineas?” ( Fredeman, Correspondence, 73.293 ). On June 9, 1874 he told Hake “of a picture (now just on completion, having been some time delayed till roses could be got) called Dîs Manibus,” His account of the picture to Hake adds some important details, “representing a Roman widow by the cinerary urn of her husband, playing her elegy on two small harps, a hand to each. I think it is one of my best & indeed shows advance: I should like to have shown you the classical drapery of which it very chiefly consists. I perched your photograph of the Fates before my eyes while I painted it & tried to get a faint reflex of that kind of beauty.

Ligeia Siren 1873

Ligeia Siren 1873

The female model (name unknown) was found for DGR by Mr. Dunn.

—онет –оссетти к картине «ћорские чары» «превращает эту сцену в развернутое

повествование». Ќа полотне изображена девушка, играюща€ на лютне, на

ветв€х – морска€ чайка. ¬ сонете звуки лютни очаровывают девушку и птицу:

она забывает о море. «¬ заключительных строках сонета возникает образ

мор€ка, который околдованный пением разбиваетс€ о скалы. ѕрекрасна€

девушка оказываетс€ русалкой, роковой сиреной, обладающей губительной

силой». —онеты и картины, по замыслу –оссетти, взаимодополн€ют друг друга,

создава€ единый синтетический жанр.

A SEA-SPELL.

(For a Picture)

Her lute hangs shadowed in the apple-tree,

While flashing flashing fingers weave the sweet-strung spell

Between its chords; and as the wild notes swell,

The sea-bird for those branches leaves the sea.

But to what sound her listening ear stoops she?

What netherworld gulf-whispers doth she hear,

In answering echoes from what planisphere,

Along the wind, along the estuary?

She sinks into her spell: and when full soon

Her lips move and she soars into her song,

What creatures of the midmost main shall throng

In furrowed surf-clouds to the summoning rune:

Till he, the fated mariner, hears her cry,

And up her rock, bare-breasted, comes to die?

1869.

"„ј–ќƒ≈… ј"

( картине)

”крыта лютн€, в листь€х утопа€,

ѕокуда пальцы лЄгкие скольз€т,

“ревожа струны и сплета€ лад

„арующий; на зов еЄ морска€

—тремитс€ чайка. не слышна ль ина€,

«ловеща€ в нем музыка, как шепот

»з преисподней, порожда€ ропот,

„то мчитс€ эхом вдоль реки, стена€?

не этой ли мелодией стру€сь,

ќна, как морок, порождает чары

» будит все подводные кошмары,

— чудовищами мор€ един€сь?

“от, кто еЄ услышит, обречен:

—трем€сь к еЄ скале, погибнет он.

1869.

перевод “амары азаковой.

ћетки: Gabriel Charls Dante Rossetti ƒанте √абриэль –оссетти ћари€ ‘ранческа |

–ќ——≈““» 1871-187 |

ƒневник |

–ќ——≈““» 1871 - 1874. ∆≈Ќў»Ќџ, »√–јёў»≈ Ќ—“–”ћ≈Ќ“ј’.

— 1871 по 1874 годы –оссетти создал четыре картины, изображающих женщин, играющих на музыкальных инструментах: La Girlandata, Veronica Veronese, The Bower Meadow и Roman Widow. ѕредполагалось, что их купит E. R. Layland , но он очень требовательно относилс€ к цвету, размеру и форме картины, стрем€сь достичь определЄнного декоративного эффекта (он декорировал свой дом) он предпочЄл картины с единственной женской фигурой и купил лишь Veronica Veronese, и Roman Widow.

Veronica Veronese

Veronica Veronese

The painting is one of the most important among the many Venetian-inspired pictures that dominate DGR's artistic output during the 1860s and 1870s. Elaborately decorative, it is an excellent example of the abstract way DGR handles ostensibly figurative subject matter. As its various commentators have noticed, the picture represents “the artistic soul in the act of creation” (Ainsworth 97). It is a visionary portrait of that soul as it had been incarnated in the practise of Paolo Veronese.

Production History

Begun in January 1872 without any explicit commission, the painting was bought by Frederick Leyland as soon as DGR told him about it, and described his intentions for the work. DGR completed it in March of the same year and sent it to Leyland at that time.

Iconograpic

The French quotation on the picture frame, supposedly from The Letters of Girolamo Ridolfi, was actually written by DGR or possibly Swinburne. It constitutes a kind of explanation of some of the picture's most important iconographical features: “Suddenly leaning forward, the Lady Veronica rapidly wrote the first notes on the virgin page. Then she took the bow of her violin to make her dream reality; but before commencing to play the instrument hanging from her hand, she remained quiet a few moments, listening to the inspiring bird, while her left hand strayed over the strings searching for the supreme melody, still elusive. It was the marriage of the voices of nature and the soul—the dawn of a mystic creation” (this is Rowland Elzea's translation of the French text on the picture frame). The “marriage” noted here is emblematically represented in the figure of the uncaged bird, which stands simultaneously as a figure of nature and of the soul.

Sarah Phelps Smith has explicated the picture's flower symbolism: the bird cage is decorated with camomile, or “energy in adversity”; the primroses symbolize youth and the daffodils (narcissi) stand for reflection or meditation. But David Nolta argues that the camomile is in fact celandine, which in herbal lore was a notable specific for diseases of the eyes. (Nolta's autobiographical reading of the picture is greatly strengthened by this view of the flower symbolism.)

Pictorial

The green velvet dress in the picture was borrowed from Jane Morris, the background drapery is a Renaissance brocade, the jewelry is Indian silver, the violin is from DGR's collection of musical instruments. The fan hanging at her side is the same as that which appears extended in Monna Vanna . The musical manuscript showing the first bars of a composition seems in debt to George Boyce, to whom DGR wrote in March 1872 asking if he “had any old written music & could you lend me such” (quoted in Surtees, A Catalogue Raisonné I. 128).

Literary

The french inscription attributed to Girolamo Ridolfi is almost certainly the work of Swinburne.

Ќачата в €нваре 1872 года без определЄнного заказа

Water Willow

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Provenance

¬ќƒяЌјя »¬ј.

ћасло. 13 на 10 1/2 дюйма.

1871 год

ћодель ƒжейн ћоррис.

артина переписана в 1893 году ‘аерфаксом ћюрреем.

¬ насто€щее врем€ находитс€ в музее ¬илмингтонского общеста из€щных искусств в ƒелаваре.

Beata Beatrix (replica) 1871-1873

ћетки: ƒанте √абриэль –оссетти Gabriel Charls Dante Rossetti ƒжон ”иль€м ѕолидори |

–ќ——≈““» 1871 - 74 |

ƒневник |

–ќ——≈““» 1873

«–ождественска€ песнь» — картина , созданна€ в 1874 году.

–анее (в 1857—58 годах) –оссетти уже создал работу с таким же названием, но в иной технике и композиции. Ќатурщицей дл€ картины стала не столь часто по€вл€вша€с€ на его работах Ёллен —мит. –оссетти увидел —мит на „елси стрит в 1863 году. расота Ёллен отличалась от привычных натурщиц с работ –оссетти, хот€ еЄ округлые черты лица и полные губы имели некоторое сходство с ‘анни орнфорт, красота которой, по мнению –оссетти, к тому времени начала ув€дать. ¬ отличие от ƒжейн ћоррис, јлексы ”айлдинг и –ут √ерберт, обладавшими острыми и характерными чертами лица и позировавших дл€ типажей роковых женщин, Ёллен —мит обладала более м€гкими и чувственными чертами лица.

јссистент –оссетти √енри “реффри ƒанн описывал эту картину как «ƒевушка в блест€щей восточной одежде малинового цвета с узором из золотой нитей, играюща€ на струнном инструменте и поюща€ Hodie Jesu Christus natus est Hallelujah». —трока из песни о рождении ’риста начертана на раме картины. —троки вз€ты из одной из кол€док, которые –оссетти собирал, записывал и переводил со среднеанглийского €зыка.

«–ождественска€ песнь» одна из серии женских портретов с музыкальными инструментами и схожей композицией (женщины изображены по по€с и в объЄмных одеждах); за ней далее последовали музыкальные портреты «La Mandolinata», «La Ghirlandata» «¬ероника ¬еронезе», «ћорские чары» и другие. —в€зь женской красоты, музыки и экзотической одежды и деталей декора была одной из отличительных черт нового художественного стил€ Ѕритании 1860-х и 1870-х годов, в котором сочетались элементы эпохи ¬озрождени€, восточного искусства и классики. ÷ентральным образом на полотнах художников стала женщина-музыкант, отрешЄнна€ задумчивости и своей игре; при этом сама музыка может быть как романтичной, так и трагичной (как на портрете –оссетти «–имска€ вдова»); художник стремилс€ создать своей работой настроение, вызванное неслышимой музыкой. ¬осточна€ мандолина с двум€ струнами принадлежала самому –оссетти; этот инструмент уже по€вл€лс€ на его других произведени€х. ѕлатье Ёллен —мит уже по€вл€лось на ней же на картине –оссетти «¬озлюбленна€».

La Girlandata 1873.

WMR's early commentary on the picture is much to the point: “The name La Ghirlandata may be translated ‘The Garlanded Lady,’ or ‘The Lady of the Wreath.’ The personage is represented singing, as she plays on a musical instrument; two youthful angels listen. The flowers which are prominent in the picture were intended by my brother for the poisonous monkshood: I believe he made a mistake, and depicted larkspur instead. I never heard him explain the underlying significance of this picture: I suppose he purposed to indicate, more or less, youth, beauty, and the faculty for art worthy of a celestial audience, all shadowed by mortal doom” ( WMR, DGR: Designer and Writer, 86-87 ). But it seems quite clear that the picture is also a (so to speak) Venetian rendering of Keats's singing and garlanded “Belle Dame Sans Merci”. The picture thus connects back to some of DGR's earliest work, such as the drawing of La Belle Dame Sans Merci as well as to several of the late, ominous pictures, like Ligeia Siren.

DGR was working on the picture in early July 1873, and by the middle of the month it had been paid for by William Graham (£840) and was, DGR told Charles Howell, “well advanced”. On August 23 he wrote to Watts-Dunton that “I have now nearly finished [a picture] I call La Ghirlandata. It contains three heads—a lady playing on a harp and two angels listening—and an infinity of other material—and in brilliancy is more like the Beloved than any other picture of mine you have seen. It belongs to Graham, who wants it in Scotland, but perhaps I may send it for a few days to London to show to a few”. He described the picture to Treffry Dunn in these terms: “The one I am doing for him now is not B[lesse]d Dam[oze]l but that figure playing on the queer old harp which I drew from Miss W[ilding] when you were here with her. The two heads of little May are at the top of the picture. It will really be a successful thing I am sure now, and is getting fast towards completion, but I have not yet got the frame. It ought to put Graham in a good humour and I am glad he is to have it as he is the only buyer I have who is worth a damn.” And to William Bell Scott he wrote even more enthusiastically: “For some six weeks past I have been at work solely on a picture now just finished and called La Ghirlandata—about 4 feet by 3. It is a woman playing on a sort of solid harp I have—an instrument stringed on both sides and very paintable in form. Behind her two angels lean through foliage and listen, and there is an immensity of work in the picture which is quite full of flowers and leaves all most carefully done from nature. It is the greenest picture in the world I believe—the principal figure being dressed in green and completely surrounded with glowing green foliage. I believe it is my very best picture—no inch of it worse than another.”

Ёта картина принадлежит к группе декоративных полотен, изображающих женщин, играющих на музыкальных инструментах. — 1871 по 1874 годы –оссетти создал четыре картины этой тематики, кроме La Girlandata это Veronica Veronese, The Bower Meadow и Roman Widow.

¬иль€м ћайкл –оссетти, комментиру€ картину, утверждал, что название можно перевести как Ћеди, увенчанна€ гирл€ндой или венком. дама играет на музыкальном инструменте и поЄт, а два юных ангела слушают. –оссетти задумал, что цветы на переднем плане картины - €довитый аконит, но ошибс€ и изобразил жимолость.

–оссетти описыва€ картину, как "самую зелЄную картину в мире". ѕриходит на ум "таможенник –уссо" с его джунгл€ми и тридцатью оттенками зелЄного.

ƒанте –оссетти никогда не объ€сн€л смысл картины, но ћайкл –оссетти предполагал, что он просто хотел изобразить молодость, красоту и искусство, достойное внимани€ свыше. » над всем этим тень судьбы всех смертных. —овершенно очевидно, что картина €вл€етс€ "венецианской" переработкой поющей и украшенной гирл€ндой “Belle Dame Sans Merci” итса. артина имеет €вную св€зь с ранними работами –оссети, такими как “La Belle Dame Sans Merci”. и с некоторыми поздними зловещими картинами, такими как Ligeia Siren. –оссетти начал работу над картиной в начале июл€, а в середине мес€ца получил аванс 840 фунтов от William Graham . ѕо поводу чего написал „арльзу Charles Howell "неплохо авансирован". 23 августа он написал Watts-Dunton, что почти закончил картину, которую назвал La Girlandata. " Ќа ней три головы - дама играюща€ на арфе, и два слушающих ангела, а также бесконечное количество других деталей. »з виденных тобой моих картин она по €ркости больше всего похожа на ¬озлюбленную. ќна принадлежит Graham, который хочет получить еЄ в Ўотландии, но, возможно, € пошлю еЄ на несколько дней в Ћондон, показать кое-кому.Treffry Dunn он описывал картину так: та, что € пишу сейчас, это не Blessed Damsel, это дама, играюща€ на странной старомодной арфе, которую € рисовал у Miss W[ilding] ,когда ¬ы также были у неЄ. ¬ верхней части картины две головки юной ћэй. артина быстро двигаетс€ к завершению и € уверен, что она будет успешной. Ќо € ещЄ не получил раму. я считаю, что Graham будет доволен и рад,что именно он получит картину, так как это мой единственный сто€щий покупатель. William Bell Scott он писал с ещЄ большим энтузиазмом: "ќколо шести недель € работаю над картиной, которую почти закончил и назвал La Girlandata - 4 на 3 фута.

»зображающую женщину, играющую на старинной арфе со струнами с обеих сторон и очень живописную по форме. —зади два ангела склон€ютс€ сквозь листву и слушают". Ќад картиной пришлось поработать, так как много цветов и листьев тщательно изображенных с натуры. Ёто сама€ зелЄна€ картина в мире - главна€ фигура одета в зелЄное и полностью окружена €рко зелЄной листвой. я считаю эту картиной моей лучшей, во вс€ком случае ничуть не хуже других. јрфа украшена белыми крыль€ми - символом пролетающего стремительно времени, а гирл€нда, давша€ название картине, состоит из роз и медуницы - символов сексуальности дл€ –оссетти.

јлекса ¬айлдинг позировала дл€ музицирующей женщины, а ћэй ћоррис дл€ ангелов.

May Morris 1872

May Morris 1872

May Morris 1871

Model: May Morris. Younger daughter of William and Jane Morris (b. 1862).

Medium: Probably chalk. Surtees says oil or watercolor, but in a letter DGR describes a chalk drawing of May Morris.

Jenny Morris 1871.

Jenny Morris 1871.

«абавные картинки, не скажешь, что девочкам 9 и 10 лет соответственно. » всЄ –оссетти на мамку сбиваетс€.

Roman Widow

When Frederick Stephens was preparing his article on DGR's new works for The Athenaeum, eventually published on August 14, 1875, DGR supplied him with this commentary: “Dîs Manibus. The title here suggests the subject—that of a Roman widow seated in the funeral vault beside her husband's cinerary urn, the inscription on which is headed with the invariable words as given above; and playing on two harps (as seen in some classical examples) an elegy ‘to the Divine Manes.’ She is robed in white—the mourning of noble ladies in Rome. The antique form of the harps is rendered in tortoiseshell chiefly with fittings of ebony or dark horn embossed in silver. The harp on which her right hand plays is wound with wild roses; and beneath the urn, across the wall of green marble, is a large festoon of garden roses, repeating as it were the festoon to be almost universally found on such urns and which this one displays round its inscription. About the urn is wound the widow's wedding-girdle of silver, dedicated to the dead as to the living husband. The moment chosen must be supposed to belong to those special occasions on which the Romans solemnized mortuary rites, and which recurred at intervals during the year” ( Fredeman, Correspondence, 75.93 ).

The painting is particularly important because of a set of strange and suggestive relationships that it has with other works by DGR that date from 1872-1877, especially Veronica Veronese, La Ghirlandata, and A Sea Spell. These four pictures share a number of features, motivic and compositional, even as their titles and nominal conceptions are very different. Considered together, they exhibit as it were four facets or aspects of a single iconic figure of highly ambiguous import.

For The Roman Widow in particular, DGR's own title—Dis Manibus—connects it to his trenchant epigram on Flaubert, written in 1880 after DGR had read of Flaubert's death. Titled by DGR “Dis Manibus”, the epigram draws a parallel between the decadence of Nero's Rome and the decadence of the Second Empire. DGR's treatment of all these materials draws his work into the same dark vortex, a fact underscored in the epigram, where the dying words of two Roman emperors, Vitellius and Nero, represent an antithesis of the glorious and the dreadful.

All of these pictures focus on a musical icon that traditionally represents an ideal order aesthetically pursued. Pater's famous pronouncement in “The School of Giorgione”, that “all art aspires to the condition of music”, is certainly being represented here. But in DGR's case the music—and therefore the practice of art—bears as well terrible meanings that Pater's work does not bring forward in this way.DGR began the picture around October 1873, as his letter to Leyland of October 4, describing the plan of the work indicates: “This I have cartooned from nature and am now beginning to paint it. It is called Dis Manibus—the dedicatory inscription to the Manes, the initials of which (D. M.) we find heading the epitaphs in Roman cinerary urns. In the picture, a lady sits in the ‘Columbarium’ beside her husband's urn which stands in a niche in the wall, wreathed about with roses and having her silver marriage-girdle hanging among them. Her dress is white—the mourning of nobles in Rome—and as she sits she plays on two harps (one in her arm and one lying beside her) her elegy addressed ‘Dis Manibus.’ The white marble background and urn, the white drapery and white roses will combine I trust to a lovely effect, and the expression will I believe be as beautiful and elevated as any I have attempted. Do you like me to consider this picture as yours at 800 guineas?” ( Fredeman, Correspondence, 73.293 ). On June 9, 1874 he told Hake “of a picture (now just on completion, having been some time delayed till roses could be got) called Dîs Manibus,” His account of the picture to Hake adds some important details, “representing a Roman widow by the cinerary urn of her husband, playing her elegy on two small harps, a hand to each. I think it is one of my best & indeed shows advance: I should like to have shown you the classical drapery of which it very chiefly consists. I perched your photograph of the Fates before my eyes while I painted it & tried to get a faint reflex of that kind of beauty.

Ligeia Siren 1873

Ligeia Siren 1873

The female model (name unknown) was found for DGR by Mr. Dunn.

—онет –оссетти к картине «ћорские чары» «превращает эту сцену в развернутое

повествование». Ќа полотне изображена девушка, играюща€ на лютне, на

ветв€х – морска€ чайка. ¬ сонете звуки лютни очаровывают девушку и птицу:

она забывает о море. «¬ заключительных строках сонета возникает образ

мор€ка, который околдованный пением разбиваетс€ о скалы. ѕрекрасна€

девушка оказываетс€ русалкой, роковой сиреной, обладающей губительной

силой». —онеты и картины, по замыслу –оссетти, взаимодополн€ют друг друга,

создава€ единый синтетический жанр.

A SEA-SPELL.

(For a Picture)

Her lute hangs shadowed in the apple-tree,

While flashing flashing fingers weave the sweet-strung spell

Between its chords; and as the wild notes swell,

The sea-bird for those branches leaves the sea.

But to what sound her listening ear stoops she?

What netherworld gulf-whispers doth she hear,

In answering echoes from what planisphere,

Along the wind, along the estuary?

She sinks into her spell: and when full soon

Her lips move and she soars into her song,

What creatures of the midmost main shall throng

In furrowed surf-clouds to the summoning rune:

Till he, the fated mariner, hears her cry,

And up her rock, bare-breasted, comes to die?

1869.

"„ј–ќƒ≈… ј"

( картине)

”крыта лютн€, в листь€х утопа€,

ѕокуда пальцы лЄгкие скольз€т,

“ревожа струны и сплета€ лад

„арующий; на зов еЄ морска€

—тремитс€ чайка. не слышна ль ина€,

«ловеща€ в нем музыка, как шепот

»з преисподней, порожда€ ропот,

„то мчитс€ эхом вдоль реки, стена€?

не этой ли мелодией стру€сь,

ќна, как морок, порождает чары

» будит все подводные кошмары,

— чудовищами мор€ един€сь?

“от, кто еЄ услышит, обречен:

—трем€сь к еЄ скале, погибнет он.

1869.

перевод “амары азаковой.

ћетки: Gabriel Charls Dante Rossetti ƒанте √абриэль –оссетти ћари€ ‘ранческа |

–ќ——≈““» 1871-187 |

ƒневник |

–ќ——≈““» 1871 - 1874. ∆≈Ќў»Ќџ, »√–јёў»≈ Ќ—“–”ћ≈Ќ“ј’.

— 1871 по 1874 годы –оссетти создал четыре картины, изображающих женщин, играющих на музыкальных инструментах: La Girlandata, Veronica Veronese, The Bower Meadow и Roman Widow. ѕредполагалось, что их купит E. R. Layland , но он очень требовательно относилс€ к цвету, размеру и форме картины, стрем€сь достичь определЄнного декоративного эффекта (он декорировал свой дом) он предпочЄл картины с единственной женской фигурой и купил лишь Veronica Veronese, и Roman Widow.

Veronica Veronese

Veronica Veronese

The painting is one of the most important among the many Venetian-inspired pictures that dominate DGR's artistic output during the 1860s and 1870s. Elaborately decorative, it is an excellent example of the abstract way DGR handles ostensibly figurative subject matter. As its various commentators have noticed, the picture represents “the artistic soul in the act of creation” (Ainsworth 97). It is a visionary portrait of that soul as it had been incarnated in the practise of Paolo Veronese.

Production History

Begun in January 1872 without any explicit commission, the painting was bought by Frederick Leyland as soon as DGR told him about it, and described his intentions for the work. DGR completed it in March of the same year and sent it to Leyland at that time.

Iconograpic

The French quotation on the picture frame, supposedly from The Letters of Girolamo Ridolfi, was actually written by DGR or possibly Swinburne. It constitutes a kind of explanation of some of the picture's most important iconographical features: “Suddenly leaning forward, the Lady Veronica rapidly wrote the first notes on the virgin page. Then she took the bow of her violin to make her dream reality; but before commencing to play the instrument hanging from her hand, she remained quiet a few moments, listening to the inspiring bird, while her left hand strayed over the strings searching for the supreme melody, still elusive. It was the marriage of the voices of nature and the soul—the dawn of a mystic creation” (this is Rowland Elzea's translation of the French text on the picture frame). The “marriage” noted here is emblematically represented in the figure of the uncaged bird, which stands simultaneously as a figure of nature and of the soul.

Sarah Phelps Smith has explicated the picture's flower symbolism: the bird cage is decorated with camomile, or “energy in adversity”; the primroses symbolize youth and the daffodils (narcissi) stand for reflection or meditation. But David Nolta argues that the camomile is in fact celandine, which in herbal lore was a notable specific for diseases of the eyes. (Nolta's autobiographical reading of the picture is greatly strengthened by this view of the flower symbolism.)

Pictorial

The green velvet dress in the picture was borrowed from Jane Morris, the background drapery is a Renaissance brocade, the jewelry is Indian silver, the violin is from DGR's collection of musical instruments. The fan hanging at her side is the same as that which appears extended in Monna Vanna . The musical manuscript showing the first bars of a composition seems in debt to George Boyce, to whom DGR wrote in March 1872 asking if he “had any old written music & could you lend me such” (quoted in Surtees, A Catalogue Raisonné I. 128).

Literary

The french inscription attributed to Girolamo Ridolfi is almost certainly the work of Swinburne.

Ќачата в €нваре 1872 года без определЄнного заказа

Water Willow

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Provenance

¬ќƒяЌјя »¬ј.

ћасло. 13 на 10 1/2 дюйма.

1871 год

ћодель ƒжейн ћоррис.

артина переписана в 1893 году ‘аерфаксом ћюрреем.

¬ насто€щее врем€ находитс€ в музее ¬илмингтонского общеста из€щных искусств в ƒелаваре.

Beata Beatrix (replica) 1871-1873

ћетки: ƒанте √абриэль –оссетти Gabriel Charls Dante Rossetti ƒжон ”иль€м ѕолидори |

| —траницы: | [1] |