Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Zibi Braniecki: Multilingual Gecko – 2017-2018 – Rearchitecture |

Between 2017 and 2018 we refactored a major component of the Gecko Platform – the intl/locale module. The main motivator was the vision of Multilingual Gecko which I documented in a blog post.

Firefox 65 brought the first major user-facing change that results from that refactor in form of Locale Selection. It’s a good time to look back at the scale of changes. This post is about the refactor of the whole module which enabled many of the changes that we were able to land in 2019 to Firefox.

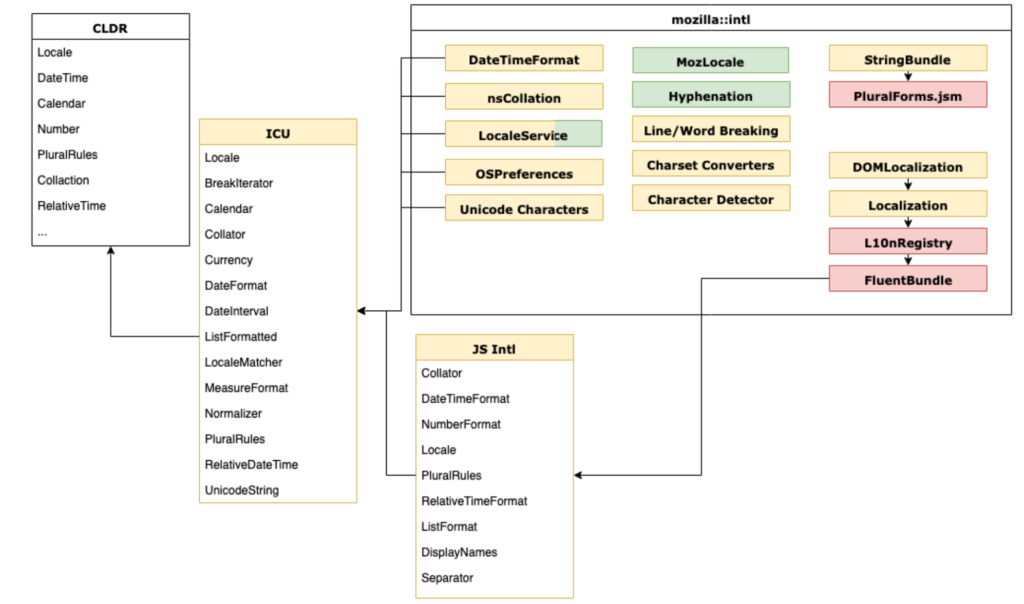

All of that work led to the following architecture:

Yellow – C++, Red – JavaScript, Green – Rust

Evolution vs Revolution

It’s very rare in software engineering that projects of scale (a Gecko module with close to 500 000 lines of code) go through such a major transition. We’ve done it a couple times, with Stylo, WebRender etc., but each case is profound, unique and rare.

There are good reasons not to touch an old code, and there are good reasons against rewriting such a large pile of code.

There’s not a lot of accrued organizational knowledge about how to handle such transitions, what common pitfalls await, and how to handle them.

That makes it even more unique to realize how smooth this change was. We started 2017 with a vision of putting a modern localization system into Firefox, and a platform that required a substantial refactor to get there.

We spent 2017 moving thousands of lines of 20 years old code around, and replacing them with a modern external library – ICU. We designed a new unified locale management and regional preferences modules, together with new internationalization wrappers finishing the year by landing Fluent into Gecko.

To give you a rough idea on the scope of changes – only 10% of ./intl/locale directory remained the same between Firefox 51 and 65!

In 2018, we started building on top of it, witnessing a reduced amount of complex work on the lower level, and much higher velocity of higher level changes with three overarching themes:

- Migrate Firefox to Fluent

- Improve Firefox locale management and multilingual use cases

- Upstream all of what we can to be part of the Web Platform

We then ended up Q1 2019 with a Fluent 1.0 release, close to 50% of DTD strings migrated to Fluent, with all major new JavaScript ECMA402 APIs based on our Gecko work and what’s even more important, with proven runtime ability to select locales from the Preferences UI.

What’s amazing to me, is that we avoided any major architectural regression in this transition. We didn’t have to revisit, remodel, revert or otherwise rethink in any substantial way any of the new APIs! All of the work, as you can see above, was put into incremental updates, deprecation of old code, standardization and integration of the new. Everything we designed to handle Firefox UI that has been proposed for standardization has been accepted, in roughly that form, by our partners from ECMA TC39 committee, and no major assumption ended up being wrong.

I believe that the reason for that success is the slow pace we took (a year of time to refactor, a year to stabilize), support from the whole organization, good test coverage and some luck.

On December 26th 2016 I filed a bug titled “Unify locale selection across components and languages“. Inside it, you can find a long list of user scenarios which we dared to tackle and which, at the time, felt completely impossible to provide.

Two years later, we had the technical means to address the majority of the scenarios listed in that bug.

Three new centralized components played a crucial role in enabling that:

LocaleService

LocaleService was the first new API. At the time, Firefox locale management was decentralized. Multiple components would try to negotiate languages for their own needs – UI chrome API, character detection, layout etc.

They would sometimes consult nsILocaleService / nsILocale which were shaped after the POSIX model and allowed to retrieve the locale based on environmental, per-OS, variables.

There was also a set of user preferences such as general.useragent.locale and intl.locale.matchOS which some of the components took into account, and others ignored.

Finally, when a locale was selected, the UI would use OS specific calls to perform internationalization operations which depended on what locale data and what intl APIs were available in the platform.

The result was that our UI could easily become inconsistent, jumping between POSIX variables, user settings, and OS settings, leading to platform-specific bugs and users stuck in a weird mid-air state with their UI being half in one locale, and half in the other.

The role of the new LocaleService was to unify that selection, provide a singleton service which will manage locale selection, negotiation and interaction with platform-specific settings.

LocaleService was written in C++ (I didn’t know Rust at the time), and quickly started replacing all hooks around the platform. It brought four major concepts:

- All APIs accepted and returned fallback lists, rather than a single locale

- All APIs manage their state through runtime negotiation

- Unify all language tags around Unicode Locale Identifier standard

- Events were fired to notify users on locale changes

The result, combined with the introduction of IPC for LocaleService, led us in the direction of cleaner system that maintains its state and can be reasoned about.

In the process, we kept extending LocaleService to provide the lists of locales that we should have in Gecko, both getters and setters, while maintaining the single source of truth and event driven model for reacting to runtime locale changes.

That allowed us to make our codebase ready for, first locale selection, and then runtime locale switching, that Fluent was about to make possible.

Today LocaleService is very stable, with just 8 bugs open, no feature changes since September 2018, up-to-date documentation and a ~93% test coverage.

OSPreferences

With the centralization of internationalization API around our custom ICU/CLDR instance, we needed a new layer to handle interactions with the host environment. This layer has been carved out of the old nsILocaleService to facilitate learning user preferences set in Windows, MacOS, Gnome and Android.

It has been a fun ride with incremental improvements to handle OS-specific customizations and feed them into LocaleService and mozIntl, but we were able to accomplish the vast majority of the goals with minimum friction and now have a sane model to reason about and extend as we need.

Today OSPreferences is very stable, with just 3 bugs open, no feature changes since September 2018, up-to-date documentation and a ~93% test coverage.

mozIntl

With LocaleService and OSPreferences in place we had all the foundation we needed to negotiate a different set of locales and customize many of the intl formatters, but we didn’t have a way to separate what we expose to the Web from what we use internally.

We needed a wrapper that would allow us to use the JS Intl API, but with some customizations and extensions that are either not yet part of the web standard, or, due to fingerprinting, cannot be exposed to the Web.

We developed `mozIntl` to close that gap. It exposes some bits that are internal only, or too early for external adoption, but ready for the internal one.

mozIntl is pretty stable now, with a few open bugs, 96% test coverage and a lot of its functionality is now in the pipeline to become part of ECMA402. In the future we hope this will make mozIntl thinner.

2019

In 2019, we were able to focus on the migration of Firefox to Fluent. That required us to resolve a couple more roadblocks, like startup performance and caching, and allowed us to start looking into the flexibility that Fluent gives to revisit our distribution channels, build system models and enable Gecko based applications to handle multilingual input.

Gecko is, as of today, a powerful software platform with a great internationalization component leading the way in advancing Web Standards and fulfilling the Mozilla mission by making the Web more accessible and multilingual. It’s a great moment to celebrate this achievement and commit to maintain that status.

https://diary.braniecki.net/2019/12/04/multilingual-gecko-2017-2018-rearchitecture/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Using WebAssembly from .NET with Wasmtime |

Wasmtime, the WebAssembly runtime from the Bytecode Alliance, recently added an early preview of an API for .NET Core, Microsoft’s free, open-source, and cross-platform application runtime. This API enables developers to programmatically load and execute WebAssembly code directly from their .NET programs.

.NET Core is already a cross-platform runtime, so why should .NET developers pay any attention to WebAssembly?

There are several reasons to be excited about WebAssembly if you’re a .NET developer, such as sharing the same executable code across platforms, being able to securely isolate untrusted code, and having a seamless interop experience with the upcoming WebAssembly interface types proposal.

Share more code across platforms

.NET assemblies can already be built for cross-platform use, but using a native library (for example, a library written in C or Rust) can be difficult because it requires native interop and distributing a platform-specific build of the library for each supported platform.

However, if the native library were compiled to WebAssembly, the same WebAssembly module could be used across many different platforms and programming environments, including .NET; this would simplify the distribution of the library and the applications that depend on it.

Securely isolate untrusted code

The .NET Framework attempted to sandbox untrusted code with technologies such as Code Access Security and Application Domains, but ultimately these failed to properly isolate untrusted code. As a result, Microsoft deprecated their use for sandboxing and ultimately removed them from .NET Core.

Have you ever wanted to load untrusted plugins in your application but couldn’t figure out a way to prevent the plugin from invoking arbitrary system calls or from directly reading your process’ memory? You can do this with WebAssembly because it was designed for the web, an environment where untrusted code executes every time you visit a website.

A WebAssembly module can only call the external functions it explicitly imports from a host environment, and may only access a region of memory given to it by the host. We can leverage this design to sandbox code in a .NET program too!

Improved interoperability with interface types

The WebAssembly interface types proposal introduces a way for WebAssembly to better integrate with programming languages by reducing the amount of glue code that is necessary to pass more complex types back and forth between the hosting application and a WebAssembly module.

When support for interface types is eventually implemented by the Wasmtime for .NET API, it will enable a seamless experience for exchanging complex types between WebAssembly and .NET.

Diving into using WebAssembly from .NET

In this article we’ll dive into using a Rust library compiled to WebAssembly from .NET with the Wasmtime for .NET API, so it will help to be a little familiar with the C# programming language to follow along.

The API described here is fairly low-level. That means that there is quite a bit of glue code required for conceptually simple operations, such as passing or receiving a string value.

In the future we’ll also provide a higher-level API based on WebAssembly interface types which will significantly reduce the code required for the same operations. Using that API will enable interacting with a WebAssembly module from .NET as easily as you would a .NET assembly.

Note also that the API is still under active development and will change in backwards-incompatible ways. We’re aiming to stabilize it as we stabilize Wasmtime itself.

If you’re reading this and you aren’t a .NET developer, that’s okay! Check out the Wasmtime Demos repository for corresponding implementations for Python, Node.js, and Rust too!

Creating the WebAssembly module

We’ll start by building a Rust library that can be used to render Markdown to HTML. However, instead of compiling the Rust library for your processor architecture, we’ll be compiling it to WebAssembly so we can use it from .NET.

You don’t need to be familiar with the Rust programming language to follow along, but it will help to have a Rust toolchain installed if you want to build the WebAssembly module. See the homepage for Rustup for an easy way to install a Rust toolchain.

Additionally, we’re going to use cargo-wasi, a command that bootstraps everything we need for Rust to target WebAssembly:

cargo install cargo-wasi

Next, clone the Wasmtime Demos repository:

git clone https://github.com/bytecodealliance/wasmtime-demos.git

cd wasmtime-demos

This repository includes the markdown directory that contains a Rust library. The library wraps a well-known Rust crate that can render Markdown as HTML. (Note for .NET developers: a crate is like a NuGet package, in a way).

Let’s build the markdown WebAssembly module using cargo-wasi:

cd markdown

cargo wasi build --release

There should now be a markdown.wasm file in the target/wasm32-wasi/release directory.

If you’re curious about the Rust implementation, open src/lib.rs; it contains the following:

use pulldown_cmark::{html, Parser};

use wasm_bindgen::prelude::*;

#[wasm_bindgen]

pub fn render(input: &str) -> String {

let parser = Parser::new(input);

let mut html_output = String::new();

html::push_html(&mut html_output, parser);

return html_output;

}

The Rust library is exporting only a single function, render, that takes a string (the Markdown) as input and returns a string (the rendered HTML). All of the code required to parse Markdown and translate it to HTML is provided by the pulldown-cmark crate.

Let’s step back and simply appreciate what is about to happen here. We’re taking a popular Rust crate, wrapping it with a few lines of code that exposes the functionality as a WebAssembly function, and then compiling it to a WebAssembly module that we can load from .NET regardless of the platform we’re running on. How cool is that!?

Peeking under the hood of a WebAssembly module

Now that we have the WebAssembly module we’re going to use, what does it need from a host to function and what functionality does it offer the host?

To figure that out, let’s disassemble the module to a textual representation using the wasm2wat tool from the WebAssembly Binary Toolkit to a file called markdown.wat:

wasm2wat markdown.wasm --enable-multi-value > markdown.wat

Note: the --enable-multi-value option enables support for functions that return multiple values and is required to disassemble the markdown module.

What the module needs from a host

The module’s imports define what the host should provide for the module to work.

Here are the imports for the markdown module:

(import "wasi_unstable" "fd_write" (func $fd_write (param i32 i32 i32 i32) (result i32)))

(import "wasi_unstable" "random_get" (func $random_get (param i32 i32) (result i32)))

This tells us that the module will need two functions from the host: fd_write and random_get. These are actually WebAssembly System Interface (WASI) functions that have well-defined behavior: fd_write is used to write data to a file descriptor and random_get will fill a buffer with random data.

Shortly we’ll implement these functions for a .NET host, but it is important to understand that this module can only call these functions from the host; the host gets to decide how, and even if, the functions are implemented.

What the module offers a host

The module’s exports define what functionality it offers the host.

Here are the exports for the markdown module:

(export "memory" (memory 0))

(export "render" (func $render_multivalue_shim))

(export "__wbindgen_malloc" (func $__wbindgen_malloc))

(export "__wbindgen_realloc" (func $__wbindgen_realloc))

(export "__wbindgen_free" (func $__wbindgen_free))

...

(func $render_multivalue_shim (param i32 i32) (result i32 i32) ...)

(func $__wbindgen_malloc (param i32) (result i32) ...)

(func $__wbindgen_realloc (param i32 i32 i32) (result i32) ...)

(func $__wbindgen_free (param i32 i32) ...)

First, the module is exporting a memory. A WebAssembly memory is the linear address space accessible to the module; it will be the only region of memory the module can read from or write to. As the module cannot access any other region of the host’s address space directly, the exported memory is where the host will exchange data with the WebAssembly module.

Second, the module exports the render function we implemented in Rust. But wait a second, why does it have two parameters and return two values when the Rust implementation only has one parameter and one return value?

In Rust, both a string slice (&str) and an owned string (String) are represented as an address and length (in bytes) pair when compiled to WebAssembly. Thus, the WebAssembly version of the Rust function takes an address-length pair for the markdown input string and returns an address-length pair for the rendered HTML string. Here, addresses are represented as integer offsets into the exported memory.

Note that since the Rust code returns a String, which is an owned type, the caller of render will be responsible for freeing the returned memory containing the rendered string.

During the implementation of the .NET host we’ll discuss the rest of the exports.

Creating the .NET project

We will need a .NET Core SDK to create a .NET Core project, so make sure you have a 3.0 or later SDK installed.

Start by creating a directory for the project:

mkdir WasmtimeDemo

cd WasmtimeDemo

Next, create a new .NET Core console project:

dotnet new console

Finally, add a reference to the Wasmtime NuGet package:

dotnet add package wasmtime --version 0.8.0-preview2

That’s it! Now we’re ready to use the Wasmtime for .NET API to load and execute the markdown WebAssembly module.

Importing .NET code from WebAssembly

Importing .NET functions from WebAssembly is as simple as implementing the IHost interface in .NET. This only requires a public Instance property that will represent the WebAssembly module instance the host is bound to.

The Import attribute is then used to mark functions and fields as imports to a WebAssembly module.

As we discussed earlier, the module requires two imports from the host: fd_write and random_get, so let’s create implementations for those functions.

Create a file named Host.cs in the project directory and add the following content:

using System.Security.Cryptography;

using Wasmtime;

namespace WasmtimeDemo

{

class Host : IHost

{

// These are from the current WASI proposal.

const int WASI_ERRNO_NOTSUP = 58;

const int WASI_ERRNO_SUCCESS = 0;

public Instance Instance { get; set; }

[Import("fd_write", Module = "wasi_unstable")]

public int WriteFile(int fd, int iovs, int iovs_len, int nwritten)

{

return WASI_ERRNO_NOTSUP;

}

[Import("random_get", Module = "wasi_unstable")]

public int GetRandomBytes(int buf, int buf_len)

{

_random.GetBytes(Instance.Externs.Memories[0].Span.Slice(buf, buf_len));

return WASI_ERRNO_SUCCESS;

}

private RNGCryptoServiceProvider _random = new RNGCryptoServiceProvider();

}

}

The fd_write implementation simply returns an error indicating the operation isn’t supported. It is used by the module for writing errors to stderr, which will not happen for this example.

The random_get implementation fills the requested buffer with random bytes. It slices the Span representing the entire exported memory of the module so that the .NET implementation can write directly to the requested buffer without having to perform any intermediate copies. The random_get function is being called by the implementation of HashMap from Rust’s standard library.

That’s all it takes to expose .NET functions to the WebAssembly module with the Wasmtime for .NET API.

However, before we can load the WebAssembly module and use it from .NET, we need to discuss how a string gets passed from the .NET host as a parameter to the render function.

Being a good host

Based on the exports of the module, we know it exports a memory. From the host’s perspective, think of a WebAssembly module’s exported memory as being granted access to the address space of a foreign process, even though the module shares the same process of the host itself.

If you randomly write data to a foreign address space, Bad Things Happen because it’s quite easy to corrupt the state of the other program and cause undefined behavior, such as a crash or the total protonic reversal of the universe. So how can a host pass data to the WebAssembly module in a safe manner?

because it’s quite easy to corrupt the state of the other program and cause undefined behavior, such as a crash or the total protonic reversal of the universe. So how can a host pass data to the WebAssembly module in a safe manner?

Internally the Rust program uses a memory allocator to manage its memory. So, for .NET to be a good host to the WebAssembly module, it must also use the same memory allocator when allocating and freeing memory accessible to the WebAssembly module.

Thankfully, wasm-bindgen, used by the Rust program to export itself as WebAssembly, also exported two functions for that purpose: __wbindgen_malloc and __wbindgen_free. These two functions are essentially malloc and free from C, except __wbindgen_free needs the size of the previous allocation in addition to the memory address.

With this in mind, let us write a simple wrapper for these exported functions in C# so we can easily allocate and free memory accessible to the WebAssembly module.

Create a file named Allocator.cs in the project directory and add the following content:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using Wasmtime.Externs;

namespace WasmtimeDemo

{

class Allocator

{

public Allocator(ExternMemory memory, IReadOnlyList functions)

{

_memory = memory ??

throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(memory));

_malloc = functions

.Where(f => f.Name == "__wbindgen_malloc")

.SingleOrDefault() ??

throw new ArgumentException("Unable to resolve malloc function.");

_free = functions

.Where(f => f.Name == "__wbindgen_free")

.SingleOrDefault() ??

throw new ArgumentException("Unable to resolve free function.");

}

public int Allocate(int length)

{

return (int)_malloc.Invoke(length);

}

public (int Address, int Length) AllocateString(string str)

{

var length = Encoding.UTF8.GetByteCount(str);

int addr = Allocate(length);

_memory.WriteString(addr, str);

return (addr, length);

}

public void Free(int address, int length)

{

_free.Invoke(address, length);

}

private ExternMemory _memory;

private ExternFunction _malloc;

private ExternFunction _free;

}

}

This code looks complicated, but all it is doing is finding the needed exported functions by name from the module and wrapping them with an easier to use interface.

We’ll use this helper Allocator class to allocate the input string to the exported render function.

Now we’re ready to render some Markdown.

Rendering the Markdown

Open Program.cs in the project directory and replace it with the following content:

using System;

using System.Linq;

using Wasmtime;

namespace WasmtimeDemo

{

class Program

{

const string MarkdownSource =

"# Hello, `.NET`! Welcome to **WebAssembly** with [Wasmtime](https://wasmtime.dev)!";

static void Main()

{

using var engine = new Engine();

using var store = engine.CreateStore();

using var module = store.CreateModule("markdown.wasm");

using var instance = module.Instantiate(new Host());

var memory = instance.Externs.Memories.SingleOrDefault() ??

throw new InvalidOperationException("Module must export a memory.");

var allocator = new Allocator(memory, instance.Externs.Functions);

(var inputAddress, var inputLength) = allocator.AllocateString(MarkdownSource);

try

{

object[] results = (instance as dynamic).render(inputAddress, inputLength);

var outputAddress = (int)results[0];

var outputLength = (int)results[1];

try

{

Console.WriteLine(memory.ReadString(outputAddress, outputLength));

}

finally

{

allocator.Free(outputAddress, outputLength);

}

}

finally

{

allocator.Free(inputAddress, inputLength);

}

}

}

}

Let’s walk through what the code doing. Step-by-step, it:

- Creates an

Engine. The engine represents the Wasmtime runtime itself. The runtime is what enables loading and executing WebAssembly modules from .NET. - Then it creates a

Store. A store is where all WebAssembly objects, such as modules and their instantiations, are kept. There can be multiple stores in an engine, but their associated objects cannot interact with one another. - Next it creates a

Modulefrom themarkdown.wasmfile on disk. AModulerepresents the data of the WebAssembly module itself, such as what it imports and exports. A module can have one or more instantiations. An instantiation is the runtime representation of a WebAssembly module. It compiles the module’s WebAssembly instructions to instructions of the current CPU architecture, allocates the memory accessible to the module, and binds imports from the host. - It instantiates the module using an instance of the

Hostclass we implemented earlier, binding the .NET functions as imports. - Finds the memory exported by the module.

- Creates an allocator and then allocates a string for the Markdown source we want to render.

- Invokes the

renderfunction with the input string by casting the instance todynamic. This is a C# feature that enables dynamic binding of functions at runtime; think of it simply as a shortcut to searching for the exportedrenderfunction and invoking it. - Outputs the rendered HTML by reading the returned string from the exported memory of the WebAssembly module.

- Finally, it frees both the input string it allocated and the returned string that the Rust program gave us to own.

That’s it for the implementation; onwards to actually running the code!

Running the .NET program

Before we can run the program, we need to copy markdown.wasm to the project directory, as this is where we’ll run the program from. You can find the markdown.wasm file in the target/wasm32-wasi/release directory from where you built it.

From the Program.cs source above, we see that the program hard-coded some Markdown to render:

# Hello, `.NET`! Welcome to **WebAssembly** with [Wasmtime](https://wasmtime.dev)!

Run the program to render it as HTML:

dotnet run

If everything went according to plan, this should be the result:

Hello, .NET! Welcome to WebAssembly with Wasmtime!

What’s next for Wasmtime for .NET?

That was a surprisingly large amount of C# code that was necessary to implement this demo, wasn’t it?

There are two major features we have planned that will help simplify this:

- Exposing Wasmtime’s WASI implementation to .NET (and other languages)

In our implementation of

Hostabove, we had to manually implementfd_writeandrandom_get, which are WASI functions.Wasmtime itself has a WASI implementation, but currently it isn’t accessible to the .NET API.

Once the .NET API can access and configure the WASI implementation of Wasmtime, there will no longer be a need for .NET hosts to provide their own implementation of WASI functions.

-

Implementing interface types for .NET

As discussed earlier, WebAssembly interface types enable a more idiomatic integration of WebAssembly with a hosting programming language.

Once the .NET API implements the interface types proposal, there shouldn’t be a need to create an

Allocatorclass like the one we implemented.Instead, functions that use types like

stringshould simply work without having to write any glue code in .NET.

The hope, then, is that this is what it might look like in the future to implement this demo from .NET:

using System;

using Wasmtime;

namespace WasmtimeDemo

{

interface Markdown

{

string Render(string input);

}

class Program

{

const string MarkdownSource =

"# Hello, `.NET`! Welcome to **WebAssembly** with [Wasmtime](https://wasmtime.dev)!";

static void Main()

{

using var markdown = Module.Load("markdown.wasm");

Console.WriteLine(markdown.Render(MarkdownSource));

}

}

}

I think we can all agree that looks so much better!

That’s a wrap!

This is the exciting beginning of using WebAssembly outside of the web browser from many different programming environments, including Microsoft’s .NET platform.

If you’re a .NET developer, we hope you’ll join us on this journey!

The .NET demo code from this article can be found in the Wasmtime Demos repository.

The post Using WebAssembly from .NET with Wasmtime appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/12/using-webassembly-from-dotnet-with-wasmtime/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: Daily web traffic |

By late 2019, there’s an estimated amount of ten billion curl installations in the world. Of course this is a rough estimate and depends on how you count etc.

There are several billion mobile phones and tablets and a large share of those have multiple installations of curl. Then there all the Windows 10 machines, web sites, all macs, hundreds of millions of cars, possibly a billion or so games, maybe half a billion TVs, games consoles and more.

How much data are they transferring?

In the high end of volume users, we have at least two that I know of are doing around one million requests/sec on average (and I’m not even sure they are the top users, they just happen to be users I know do high volumes) but in the low end there will certainly be a huge amount of installations that barely ever do any requests at all.

If there are two users that I know are doing one million requests/sec, chances are there are more and there might be a few doing more than a million and certainly many that do less but still many.

Among many of the named and sometimes high profiled apps and users I know use curl, I very rarely know exactly for what purpose they use curl. Also, some use curl to do very many small requests and some will use it to do a few but very large transfers.

Additionally, and this really complicates the ability to do any good estimates, I suppose a number of curl users are doing transfers that aren’t typically considered to be part of “the Internet”. Like when curl is used for doing HTTP requests for every single subway passenger passing ticket gates in the London underground, I don’t think they can be counted as Internet transfers even though they use internet protocols.

How much data are browsers driving?

According to some data, there is today around 4.388 billion “Internet users” (page 39) and the world wide average time spent “on the Internet” is said to be 6 hours 42 minutes (page 50). I think these numbers seem credible and reasonable.

According to broadbandchoices, an average hour of “web browsing” spends about 25MB. According to databox.com, an average visit to a web site is 2-3 minutes. httparchive.org says the median page needs 74 HTTP requests to render.

So what do users do with their 6 hours and 42 minutes “online time” and how much of it is spent in a browser? I’ve tried to find statistics for this but failed.

@chuttenc (of Mozilla) stepped up and helped me out with getting stats from Firefox users. Based on stats from users that used Firefox on the day of October 1, 2019 and actually used their browser that day, they did 2847 requests per client as median with the median download amount 18808 kilobytes. Of that single day of use.

I don’t have any particular reason to think that other browsers, other days or users of other browsers are very different than Firefox users of that single day. Let’s count with 3,000 requests and 20MB per day. Interestingly, that makes the average data size per request a mere 6.7 kilobytes.

A median desktop web page total size is 1939KB right now according to httparchive.org (and the mobile ones are just slightly smaller so the difference isn’t too important here).

Based on the median weight per site from httparchive, this would imply that a median browser user visits the equivalent of 15 typical sites per day (30MB/1.939MB).

If each user spends 3 minutes per site, that’s still just 45 minutes of browsing per day. Out of the 6 hours 42 minutes. 11% of Internet time is browser time.

3000 requests x 4388000000 internet users, makes 13,164,000,000,000 requests per day. That’s 13.1 trillion HTTP requests per day.

The world’s web users make about 152.4 million HTTP requests per second.

(I think this is counting too high because I find it unlikely that all internet users on the globe use their browsers this much every day.)

The equivalent math to figure out today’s daily data amounts transferred by browsers makes it 4388000000 x 30MB = 131,640,000,000 megabytes/day. 1,523,611 megabytes per second. 1.5 TB/sec.

30MB/day equals a little under one GB/month per person. Feels about right.

Back to curl usage

The curl users with the highest request frequencies known to me (*) are racing away at one million requests/second on average, but how many requests do the others actually do? It’s really impossible to say. Let’s play the guessing game!

First, it feels reasonable to assume that these two users that I know of are not alone in doing high frequency transfers with curl. Purely based on probability, it seems reasonable to assume that the top-20 something users together will issue at least 10 million requests/second.

Looking at the users that aren’t in that very top. Is it reasonable to assume that each such installed curl instance makes a request every 10 minutes on average? Maybe it’s one per every 100 minutes? Or is it 10 per minute? There are some extremely high volume and high frequency users but there’s definitely a very long tail of installations basically never doing anything… The grim truth is that we simply cannot know and there’s no way to even get a ballpark figure. We need to guess.

Let’s toy with the idea that every single curl instance on average makes a transfer, a request, every tenth minute. That makes 10 x 10^9 / 600 = 16.7 million transfers per second in addition to the top users’ ten million. Let’s say 26 million requests per second. The browsers of the world do 152 million per second.

If each of those curl requests transfer 50Kb of data (arbitrarily picked out of thin air because again we can’t reasonably find or calculate this number), they make up (26,000,000 x 50 ) 1.3 TB/sec. That’s 85% of the data volume all the browsers in the world transfer.

The world wide browser market share distribution according to statcounter.com is currently: Chrome at 64%, Safari at 16.3% and Firefox at 4.5%.

This simple-minded estimate would imply that maybe, perhaps, possibly, curl transfers more data an average day than any single individual browser flavor does. Combined, the browsers transfer more.

Guesses, really?

Sure, or call them estimates. I’m doing them to the best of my ability. If you have data, reasoning or evidence to back up modifications my numbers or calculations that you can provide, nobody would be happier than me! I will of course update this post if that happens!

(*) = I don’t name these users since I’ve been given glimpses of their usage statistics informally and I’ve been asked to not make their numbers public. I hold my promise by not revealing who they are.

Thanks

Thanks to chuttenc for the Firefox numbers, as mentioned above, and thanks also to Jan Wildeboer for helping me dig up stats links used in this post.

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: How to stop third party tracking on health sites |

Is health data being used by third party trackers to target you when you’re potentially at your most vulnerable? According to an investigation by The Financial Times, a global newspaper … Read more

The post How to stop third party tracking on health sites appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/how-to-stop-third-party-tracking-on-health-sites/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Firefox 71: A year-end arrival |

Another release is upon us: please welcome Firefox 71 to the stage! This time around, we have a plethora of new developer tools features. These include the web socket message inspector, console multi-line editor mode, log on events, and network panel full text search!

And as if that wasn’t good enough, there are important new web platform features available, like CSS subgrid, column-span, Promise.allSettled, and the Media Session API.

Read on for more details of the highlights, and find the full list of additions with the links below:

Developer tools

Let’s start with our new developer tool features! Many of these were first made available in Firefox Developer Edition, and then improved based on feedback from early adopters. We’d like to thank you all for your help!

Continued speed and reliability improvements

Improvements in Firefox 71 continue our promise to provide a rock-solid and fast DevTools experience.

We know it’s important that DevTools load quickly. We have automation in place to help ensure we keep driving this time down. In 71 we got some help from the JavaScript team, when their improvements to caching scripts for startup not only made Firefox start faster, but DevTools too. One Console test got an astonishing 40% improvement while times across every panel were boosted by 8-15%!

Interaction with pretty-printed code has gotten a lot of attention. Over past releases we’ve already improved breakpoint handling and pausing. In 71, links to scripts (like from the event handler tooltip in the Inspector or the stack traces in the Console) reliably get you to the expected line, and debugging sources loaded through eval() now also works as expected.

WebSocket Message Inspector

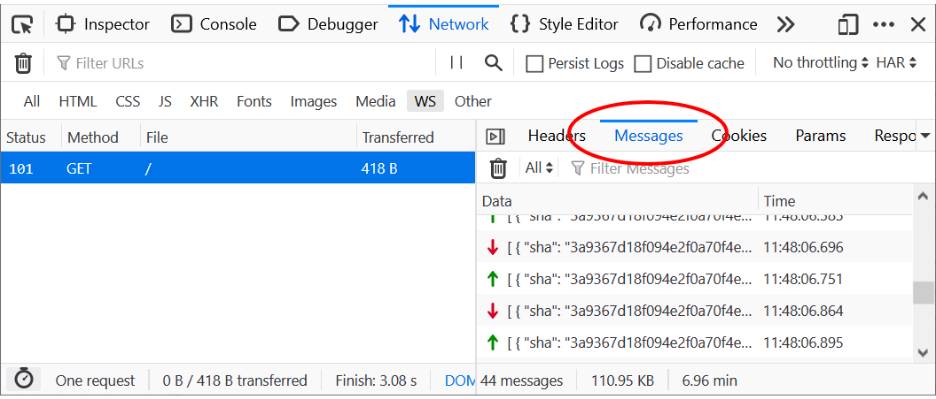

The Network panel has a new Messages tab. You can observe all messages sent and received through a WebSocket connection:

Sent frames have a green up-arrow icon, while received frames have a red down-arrow icon. You can click on an individual frame to view its formatted data.

Find out more about WebSockets and how to use the tool in this post about Firefox’s New WebSocket Inspector. Thanks a lot to Heng Yeow Tan, who worked on this feature as part of his Google Summer of Code (GSoC) internship.

Network full-text search

Sometimes you need to find a CSS file that defines a color, or work out which file generates a button label on a page. Full-text search makes this possible by letting you search through all resources in the Network Monitor. Similar to other DevTools, you can open the new panel by clicking the new “Search” icon in the toolbar or using the shortcut (Windows: Ctrl + Shift + F, Mac: Cmd + Shift + F). The full-text search will highlight matches in request/response bodies, headers, and cookies.

Tip: You can use the Network panel’s existing URL and type filters to limit which requests are being matched in search.

Thanks a lot to lloan Alas, who worked on this feature as part of his Outreachy internship.

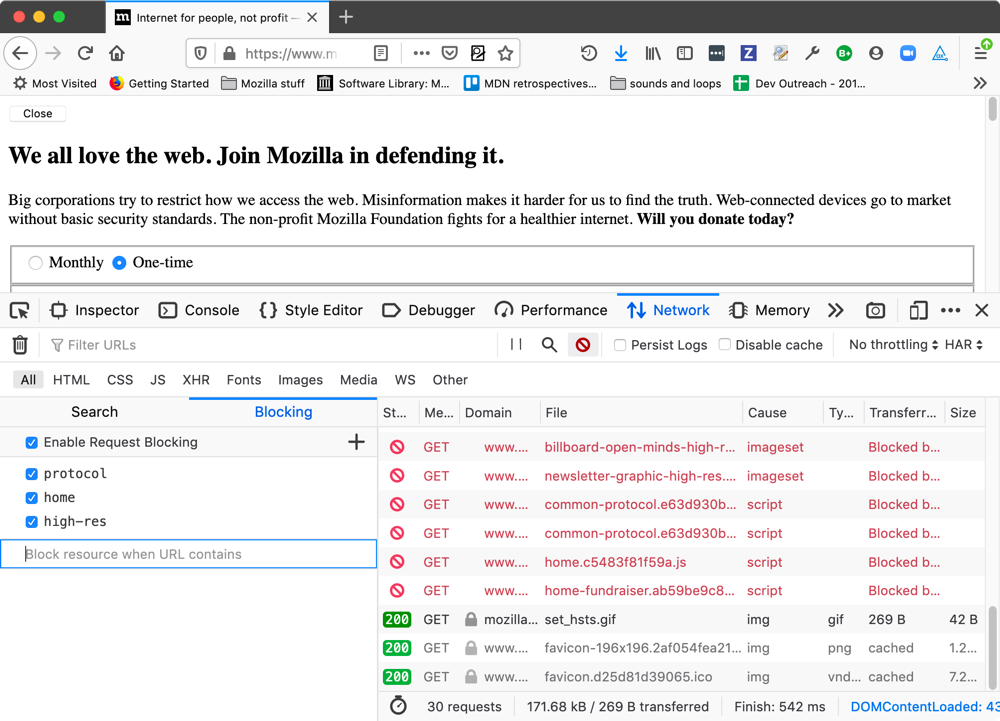

Network request blocking

Simulating blocked requests lets you test how a page loads and functions without specific files, like CSS or JavaScript. The panel is right next to the new full-text search.

You can toggle request blocking as a whole or enter individual patterns to experiment with. To make entering lists easier you can paste in multiple lines of patterns, which will be split into individual rules.

Note how blocked requests are shown in red, with a red “no entry sign” icon next to them.

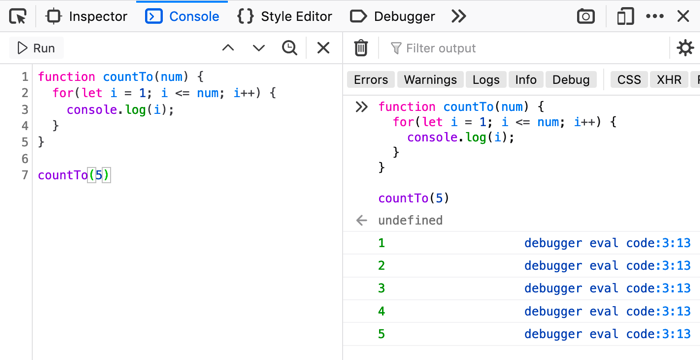

Console multi-line editor mode

Another great developer tools feature in Firefox 71 is the new multi-line console. It combines the benefits of IDEs to authoring code with the workflow of repeatedly executing code in the context of the page.

If you open the regular console, you’ll see a new icon at the end of the prompt row.

Clicking this will switch the console to multi-line mode:

Here you can enter multiple lines of code, pressing enter after each one, and then run the code using Ctrl + Enter. You can also move between statements using the next and previous arrows. The editor includes regular IDE features you’d expect, such as open/close bracket pair highlighting and automatic indentation.

We are starting with a small, simple feature set for now. We will add more based on the feedback we are already collecting.

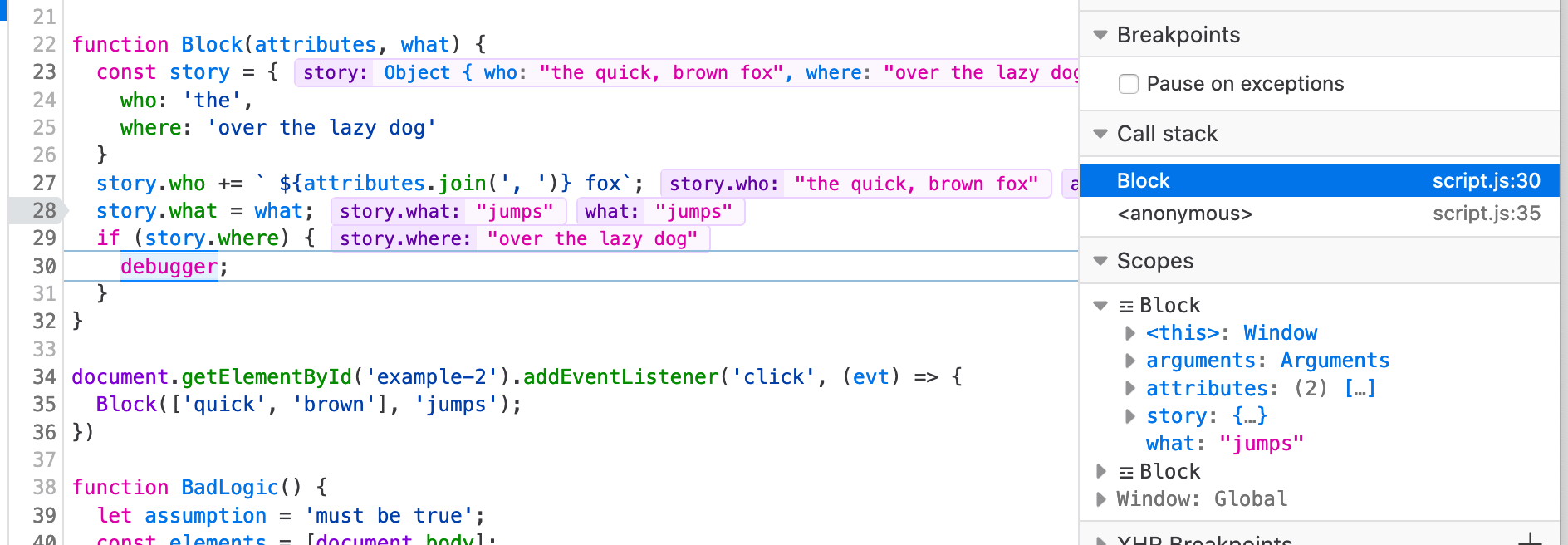

Inline variable preview in Debugger

The JavaScript Debugger now provides inline variable previewing, which is a useful timesaver when stepping through your code. Previously you’d have to scroll through the scope panel to find variable values. Or, you could hover over a variable in the source pane. Now when execution pauses, you can view relevant variable and property values directly in the source.

Using our babel-powered source mapping, preview also works for variables that have been renamed or minified by build steps. Make sure to enable this power-feature by checking Map in the Scopes pane.

If you prefer less output you can toggle preview off in the new context menu option in the source pane.

Thanks a lot to Dhyey Thakore, who worked on this feature as part of his GSoC internship.

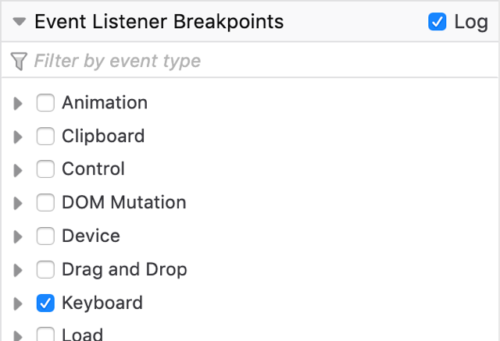

Log on Event Listeners

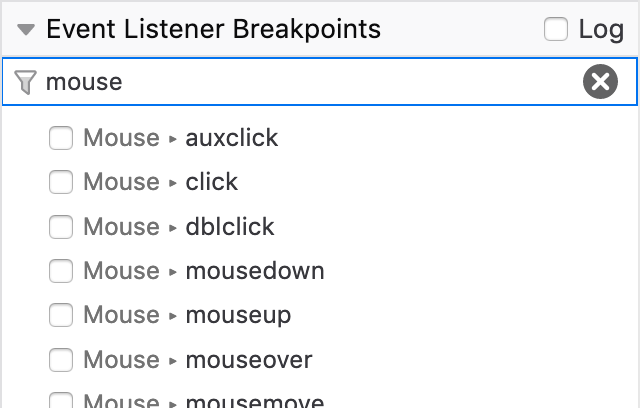

Finally, we’d like to talk a bit about updates to event listener breakpoints in 71. There are a couple of nice improvements available.

Log on events lets you explore which event handlers are being fired in which order without the need for pausing and stepping. This is inspired by Firebug’s Log DOM Event functionality but with more control over which events are monitored thanks to its tie in with Event Breakpoints.

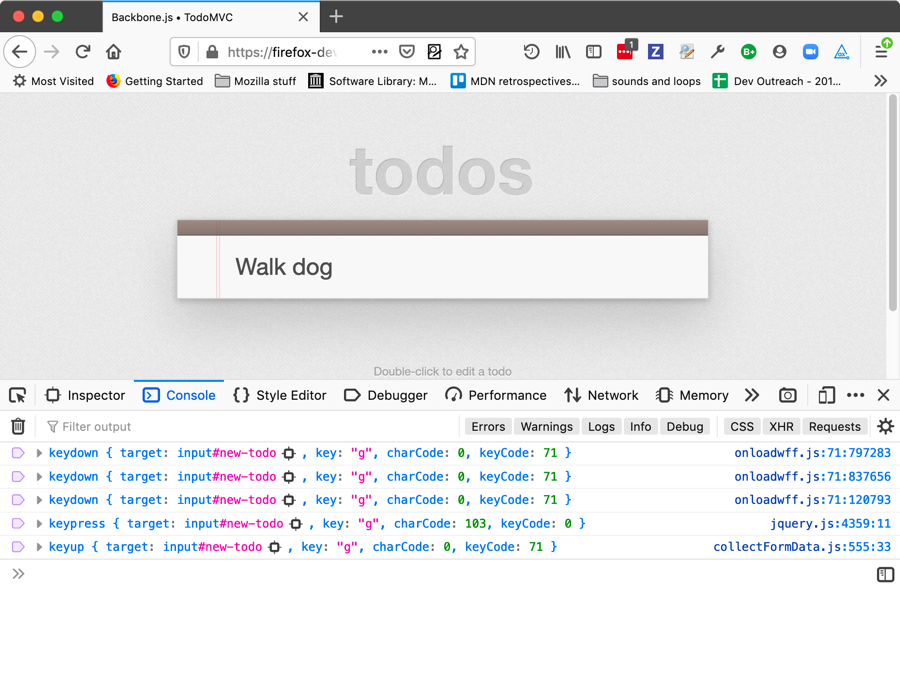

So if we choose to log keyboard events, for example, the code no longer pauses as each event is fired:

Instead, we can then switch to the console, and whenever we press a key we are given a log of where related events were fired.

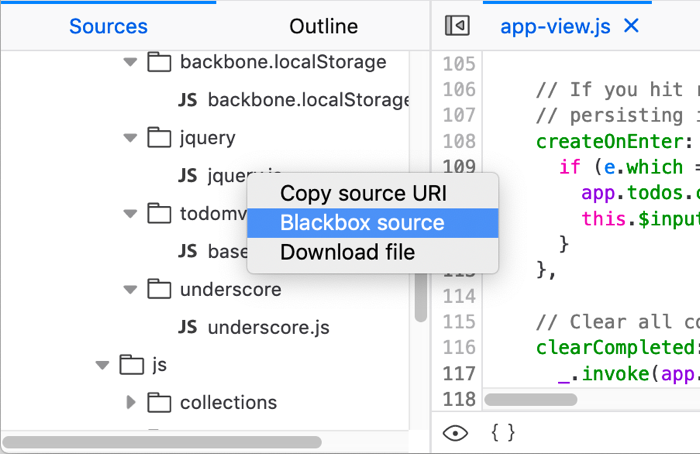

One issue here is that the console is showing that the keypress event is being fired somewhere inside jQuery. Instead, it’d be far more useful if we showed where in our own app code is calling the jQuery that fired the event. This can be done by finding jquery.js in the Sources panel, and choosing the Blackbox source option from its context menu.

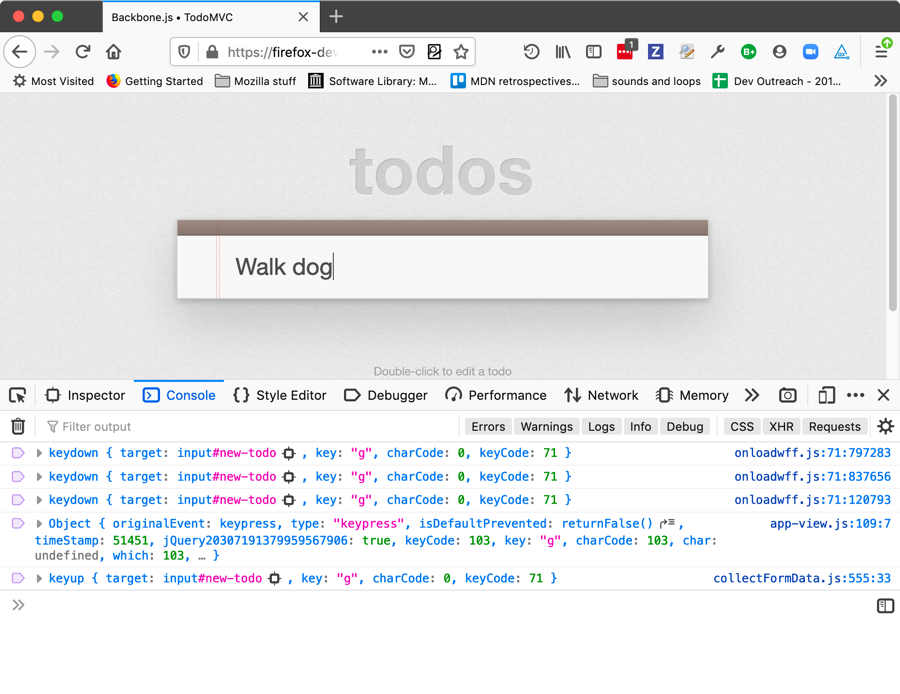

Now the logs will show where in your app jQuery was called, rather than where in jQuery the event was fired:

There is also a new Filter by event type… text input. When you click in this input and type a search term, the list of event listener types will filter by that term, allowing you to find the events you want to break on more easily.

CSS

New in CSS in 71 we have subgrid, multicol, clip-path: path, and aspect ratio mapping.

Subgrid

A feature that has been enabled in 71 after being supported behind a pref for a while, the subgrid value of grid-template-columns and grid-template-rows allows you to create a nested grid inside a grid item that will use the main grid’s tracks. This means that grid items inside the subgrid will line up with the parent’s grid tracks, making various layout techniques much easier.

.grid {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(9, 1fr);

grid-template-rows: repeat(4, minmax(100px, auto));

}

.item {

display: grid;

grid-column: 2 / 7;

grid-row: 2 / 4;

grid-template-columns: subgrid;

grid-template-rows: subgrid;

}

.subitem {

grid-column: 3 / 6;

grid-row: 1 / 3;

}We’ve also updated the developer tools’ Grid Inspector to support subgrid! Specifically, we have:

- allowed highlighting of multiple grids simultaneously.

- added a “subgrid” badge to the HTML pane that appears next to elements which have been designated as a subgrid, in the same way that the “grid” and “flex” badges already work.

- made it so that when a subgrid is highlighted, the parent is also subtly highlighted.

See the MDN Subgrid page for more details.

Multicol — column-span

CSS multicol support has moved forward in a big way with the inclusion of the column-span property in Firefox 71. This allows you to make an element span across all the columns in a multicol container (generated using column-width or column-count).

article {

columns: 3;

}

h2 {

column-span: all;

}You can find a number of useful details about column-span in the article Spanning and balancing columns.

Clip-path: path()

The path() value of the clip-path property is now enabled by default — this allows you to create a custom mask shape using a path() function, as opposed to a predefined shape like a circle or ellipse.

#clipped {

clip-path: path('M 0 200 L 0,110 A 110,90 0,0,1 240,100 L 200 340 z');

}

Aspect ratio mapping

Finally, the height and width HTML attributes on the aspect-ratio property.

This allows the browser to calculate the image’s aspect ratio early on and correct its display size before it has loaded if CSS has been applied that causes problems with the display size.

Read Mapping the width and height attributes of media container elements to their aspect-ratio for the full story.

JavaScript and Web APIs

We’ve had a few minor JavaScript changes in this release as well: Promise.allSettled(), the Media Session API, and WebGL multiview.

Promise.allSettled()

The most significant change comes with the support of the Promise.allSettled() method, which takes an array of promise objects as a parameter just like Promise.all().

However, whereas Promise.all() will fulfill only when all the promises passed to it have been fulfilled, Promise.allSettled() will fulfill when all the promises passed to it have been resolved (fulfilled or rejected).

const promise1 = Promise.resolve(3);

const promise2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => setTimeout(reject, 100, 'foo'));

const promises = [promise1, promise2];

Promise.allSettled(promises).

then((results) => results.forEach((result) => console.log(result.status)));

// expected output:

// "fulfilled"

// "rejected"Media Session API

Over in Web API land, the main new addition is partial support for the Media Session API. This API provides a standard mechanism for your content to share information about the state of media playing with the underlying operating system. It includes metadata such as artist, album, track name, or album artwork, for example.

if ('mediaSession' in navigator) {

navigator.mediaSession.metadata = new MediaMetadata({

title: 'Unforgettable',

artist: 'Nat King Cole',

album: 'The Ultimate Collection (Remastered)',

artwork: [

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/96x96', sizes: '96x96', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/128x128', sizes: '128x128', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/192x192', sizes: '192x192', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/256x256', sizes: '256x256', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/384x384', sizes: '384x384', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/512x512', sizes: '512x512', type: 'image/png' },

]

});

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('play', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('pause', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('seekbackward', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('seekforward', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('previoustrack', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('nexttrack', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

}The aim of this API is to allow users to know what’s playing, and to control it, without opening the specific page that launched it.

WebGL multiview

71 also sees the OVR_multiview2 WebGL extension exposed by default. This is an exciting new addition to the web platform that allows WebGL code to draw on multiple targets with a single draw call, improving performance in the process.

Multiview is especially exciting for WebXR code, in which case you always have to draw everything twice! Read Multiview on WebXR for more information.

User features

You can read about the most interesting user features added to Firefox 71 in the main Firefox 71 Release Notes.

We would however like to highlight Picture-in-picture (PIP). If you start playing a video on a web page, but then want to check out other content, you can activate PIP and keep the video playing in a small overlay while you continue to navigate the rest of the page (or other pages).

The post Firefox 71: A year-end arrival appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/12/firefox-71-a-year-end-arrival/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Firefox 71: A winter arrival |

Another release is upon us: please welcome Firefox 71 to the stage! This time around, we have a plethora of new developer tools features. These include the web socket message inspector, console multi-line editor mode, log on events, and network panel full text search!

And as if that wasn’t good enough, there are important new web platform features available, like CSS subgrid, column-span, Promise.allSettled, and the Media Session API.

Read on for more details of the highlights, and find the full list of additions with the links below:

Developer tools

Let’s start with our new developer tool features! Many of these were first made available in Firefox Developer Edition, and then improved based on feedback from early adopters. We’d like to thank you all for your help!

Continued speed and reliability improvements

Improvements in Firefox 71 continue our promise to provide a rock-solid and fast DevTools experience.

We know it’s important that DevTools load quickly. We have automation in place to help ensure we keep driving this time down. In 71 we got some help from the JavaScript team, when their improvements to caching scripts for startup not only made Firefox start faster, but DevTools too. One Console test got an astonishing 40% improvement while times across every panel were boosted by 8-15%!

Interaction with pretty-printed code has gotten a lot of attention. Over past releases we’ve already improved breakpoint handling and pausing. In 71, links to scripts (like from the event handler tooltip in the Inspector or the stack traces in the Console) reliably get you to the expected line, and debugging sources loaded through eval() now also works as expected.

WebSocket Message Inspector

The Network panel has a new Messages tab. You can observe all messages sent and received through a WebSocket connection:

Sent frames have a green up-arrow icon, while received frames have a red down-arrow icon. You can click on an individual frame to view its formatted data.

Find out more about WebSockets and how to use the tool in this post about Firefox’s New WebSocket Inspector. Thanks a lot to Heng Yeow Tan, who worked on this feature as part of his Google Summer of Code (GSoC) internship.

Network full-text search

Sometimes you need to find a CSS file that defines a color, or work out which file generates a button label on a page. Full-text search makes this possible by letting you search through all resources in the Network Monitor. Similar to other DevTools, you can open the new panel by clicking the new “Search” icon in the toolbar or using the shortcut (Windows: Ctrl + Shift + F, Mac: Cmd + Shift + F). The full-text search will highlight matches in request/response bodies, headers, and cookies.

Tip: You can use the Network panel’s existing URL and type filters to limit which requests are being matched in search.

Thanks a lot to lloan Alas, who worked on this feature as part of his Outreachy internship.

Network request blocking

Simulating blocked requests lets you test how a page loads and functions without specific files, like CSS or JavaScript. The panel is right next to the new full-text search.

You can toggle request blocking as a whole or enter individual patterns to experiment with. To make entering lists easier you can paste in multiple lines of patterns, which will be split into individual rules.

Note how blocked requests are shown in red, with a red “no entry sign” icon next to them.

Console multi-line editor mode

Another great developer tools feature in Firefox 71 is the new multi-line console. It combines the benefits of IDEs to authoring code with the workflow of repeatedly executing code in the context of the page.

If you open the regular console, you’ll see a new icon at the end of the prompt row.

Clicking this will switch the console to multi-line mode:

Here you can enter multiple lines of code, pressing enter after each one, and then run the code using Ctrl + Enter. You can also move between statements using the next and previous arrows. The editor includes regular IDE features you’d expect, such as open/close bracket pair highlighting and automatic indentation.

We are starting with a small, simple feature set for now. We will add more based on the feedback we are already collecting.

Inline variable preview in Debugger

The JavaScript Debugger now provides inline variable previewing, which is a useful timesaver when stepping through your code. Previously you’d have to scroll through the scope panel to find variable values. Or, you could hover over a variable in the source pane. Now when execution pauses, you can view relevant variable and property values directly in the source.

Using our babel-powered source mapping, preview also works for variables that have been renamed or minified by build steps. Make sure to enable this power-feature by checking Map in the Scopes pane.

If you prefer less output you can toggle preview off in the new context menu option in the source pane.

Log on Event Listeners

Finally, we’d like to talk a bit about updates to event listener breakpoints in 71. There are a couple of nice improvements available.

Log on events lets you explore which event handlers are being fired in which order without the need for pausing and stepping. This is inspired by Firebug’s Log DOM Event functionality but with more control over which events are monitored thanks to its tie in with Event Breakpoints.

So if we choose to log keyboard events, for example, the code no longer pauses as each event is fired:

Instead, we can then switch to the console, and whenever we press a key we are given a log of where related events were fired.

One issue here is that the console is showing that the keypress event is being fired somewhere inside jQuery. Instead, it’d be far more useful if we showed where in our own app code is calling the jQuery that fired the event. This can be done by finding jquery.js in the Sources panel, and choosing the Blackbox source option from its context menu.

Now the logs will show where in your app jQuery was called, rather than where in jQuery the event was fired:

There is also a new Filter by event type… text input. When you click in this input and type a search term, the list of event listener types will filter by that term, allowing you to find the events you want to break on more easily.

CSS

New in CSS in 71 we have subgrid, multicol, clip-path: path, and aspect ratio mapping.

Subgrid

A feature that has been enabled in 71 after being supported behind a pref for a while, the subgrid value of grid-template-columns and grid-template-rows allows you to create a nested grid inside a grid item that will use the main grid’s tracks. This means that grid items inside the subgrid will line up with the parent’s grid tracks, making various layout techniques much easier.

.grid {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(9, 1fr);

grid-template-rows: repeat(4, minmax(100px, auto));

}

.item {

display: grid;

grid-column: 2 / 7;

grid-row: 2 / 4;

grid-template-columns: subgrid;

grid-template-rows: subgrid;

}

.subitem {

grid-column: 3 / 6;

grid-row: 1 / 3;

}We’ve also updated the developer tools’ Grid Inspector to support subgrid! Specifically, we have:

- allowed highlighting of multiple grids simultaneously.

- added a “subgrid” badge to the HTML pane that appears next to elements which have been designated as a subgrid, in the same way that the “grid” and “flex” badges already work.

- made it so that when a subgrid is highlighted, the parent is also subtly highlighted.

See the MDN Subgrid page for more details.

Multicol — column-span

CSS multicol support has moved forward in a big way with the inclusion of the column-span property in Firefox 71. This allows you to make an element span across all the columns in a multicol container (generated using column-width or column-count).

article {

columns: 3;

}

h2 {

column-span: all;

}You can find a number of useful details about column-span in the article Spanning and balancing columns.

Clip-path: path()

The path() value of the clip-path property is now enabled by default — this allows you to create a custom mask shape using a path() function, as opposed to a predefined shape like a circle or ellipse.

#clipped {

clip-path: path('M 0 200 L 0,110 A 110,90 0,0,1 240,100 L 200 340 z');

}

Aspect ratio mapping

Finally, the height and width HTML attributes on the aspect-ratio property.

This allows the browser to calculate the image’s aspect ratio early on and correct its display size before it has loaded if CSS has been applied that causes problems with the display size.

Read Mapping the width and height attributes of media container elements to their aspect-ratio for the full story.

JavaScript and Web APIs

We’ve had a few minor JavaScript changes in this release as well: Promise.allSettled(), the Media Session API, and WebGL multiview.

Promise.allSettled()

The most significant change comes with the support of the Promise.allSettled() method, which takes an array of promise objects as a parameter just like Promise.all().

However, whereas Promise.all() will fulfill only when all the promises passed to it have been fulfilled, Promise.allSettled() will fulfill when all the promises passed to it have been resolved (fulfilled or rejected).

const promise1 = Promise.resolve(3);

const promise2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => setTimeout(reject, 100, 'foo'));

const promises = [promise1, promise2];

Promise.allSettled(promises).

then((results) => results.forEach((result) => console.log(result.status)));

// expected output:

// "fulfilled"

// "rejected"Media Session API

Over in Web API land, the main new addition is partial support for the Media Session API. This API provides a standard mechanism for your content to share information about the state of media playing with the underlying operating system. It includes metadata such as artist, album, track name, or album artwork, for example.

if ('mediaSession' in navigator) {

navigator.mediaSession.metadata = new MediaMetadata({

title: 'Unforgettable',

artist: 'Nat King Cole',

album: 'The Ultimate Collection (Remastered)',

artwork: [

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/96x96', sizes: '96x96', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/128x128', sizes: '128x128', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/192x192', sizes: '192x192', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/256x256', sizes: '256x256', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/384x384', sizes: '384x384', type: 'image/png' },

{ src: 'https://dummyimage.com/512x512', sizes: '512x512', type: 'image/png' },

]

});

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('play', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('pause', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('seekbackward', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('seekforward', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('previoustrack', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

navigator.mediaSession.setActionHandler('nexttrack', function() { /* Code excerpted. */ });

}The aim of this API is to allow users to know what’s playing, and to control it, without opening the specific page that launched it.

WebGL multiview

71 also sees the OVR_multiview2 WebGL extension exposed by default. This is an exciting new addition to the web platform that allows WebGL code to draw on multiple targets with a single draw call, improving performance in the process.

Multiview is especially exciting for WebXR code, in which case you always have to draw everything twice! Read Multiview on WebXR for more information.

User features

You can read about the most interesting user features added to Firefox 71 in the main Firefox 71 Release Notes.

We would however like to highlight Picture-in-picture (PIP). If you start playing a video on a web page, but then want to check out other content, you can activate PIP and keep the video playing in a small overlay while you continue to navigate the rest of the page (or other pages).

The post Firefox 71: A winter arrival appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/12/firefox-71-a-winter-arrival/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: libcurl video tutorial |

I’ve watched how my thirteen year old son goes about to acquire information about things online. I am astonished how he time and time again deliberately chooses to get it from a video on YouTube rather than trying to find the best written documentation for whatever he’s looking for. I just have to accept that some people, even some descendants in my own family tree, prefer video as a source of information. And I realize he’s not alone.

So therefore, I bring you, the…

libcurl video tutorial

My intent is to record a series of short and fairly independent episodes, each detailing a specific libcurl area. A particular “thing”, feature, option or area of the APIs. Each episode is also thoroughly documented and all the source code seen on the video is available on the site so that viewers can either follow along while viewing, or go back to the code afterward as a reference. Or both!

I’ve done the four first episodes so far, and they range from five minutes to nineteen minutes a piece. I expect that it might take me a while to just complete the list of episodes I could come up with myself. I also hope and expect that readers and viewers will think of other areas that I could cover so the list of video episodes could easily expand over time.

Feedback

If you have comments on the episodes. If you have suggestion of what to improve or subjects to cover, head over to the libcurl-video-tutorials github page and file an issue or two!

Video setup

I use a Debian Linux installation to develop on. I figure it should be similar enough to many other systems.

Video wise, in each episode I show you my text editor for code, a terminal window for building the code, running what we build in the episode and also for looking up man page information etc. And a small image of myself. Behind those three squares, there’s a photo of a forest (taken by me).

I plan to make each episode use the same basic visuals.

In the initial “setup” episode I create a generic Makefile, which we can reuse in several (all?) other episodes to build the example code easily and swiftly. I’ve previously learned that people consider Makefiles difficult, or sometimes even magic, to work with so I wanted to get that out of the way from the start and then focus more directly on actual C code that uses libcurl.

Receive data episode

Here’s the “receive data” episode as an example of how this can look.

The link: https://bagder.github.io/libcurl-video-tutorials/

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2019/12/03/libcurl-video-tutorial/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Questions About .org |

Last month, the Internet Society (ISOC) announced plans to sell the Public Interest Registry (PIR) — the organization that manages all the dot org domain names in the world — to a private equity firm named Ethos. This caught the attention of Mozilla and other public benefit orgs.

Many have called for the deal to be stopped. It’s not clear that this kind of sale is inherently bad. It is possible that with the right safeguards a private company could act as a good steward of the dot org ecosystem. However, it is clear that the stakes are high — and that anyone with the power to do so should urgently step in to slow things down and ask some hard questions.

For example: Is this deal a good thing for orgs that use these domains? Is it structured to ensure that dot org will retain its unique character as a home for non-commercial organizations online? What accountability measures will be put in place?

In a letter to ISOC, the EFF and others summarize why the stakes are high. Whoever runs the dot org registry has the power to: set (and raise) prices; define rights protection rules; and suspend or take down domains that are unlawful, a standard that varies widely from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. It is critical that whoever runs the dot org registry is a reliable steward who can be held accountable for exercising these powers fairly and effectively.

ISOC and Ethos put up a site last week called keypointsabout.org which argues that the newly privatized PIR will be just such a steward. Measures outlined on the site include the creation of a stewardship council, price caps, and the incorporation of the new PIR as a B Corp. These sound like good plans at first read, but they need much more scrutiny and detail given what is at stake.

ICANN and the ISOC board are both in a position to slow things down and offer greater scrutiny and public transparency. We urge them to step back and provide public answers to questions of interest to the public and the millions of orgs that have made dot org their home online for the last 15 years. Specific questions should include:

- Are the stewardship measures proposed for the new PIR sufficient to protect the interests of the dot org community? What is missing?

- What level of scope, authority and independence will the proposed Stewardship Council possess? Will dot org stakeholders have opportunities to weigh in on the selection of the Council and development of its bylaws and its relationship to PIR and Ethos?

- What assurances can the dot org community have that Ethos and PIR will keep their promises regarding price increases? Will there be any remedy if these promises are not kept?

- What mechanisms does PIR currently have in place to implement measures to protect free speech and other rights of domain holders under its revised contract, and will those mechanisms change in any way with the transfer of ownership and control? In particular, how will PIR handle requests from government actors?

- When is the planned incorporation of PIR as a B corp? Are there any repercussions for Ethos and/or PIR if this incorporation does not take place?

- What guarantees are in place to retain the unique character of the dot org as a home for non-commercial organizations, one of the important stewardship promises made by PIR when it was granted the registry?

- Did ISOC receive multiple bids for PIR? If yes, what criteria in addition to price were used to review the bids? Were the ICANN criteria originally applied to dot org bidders in 2002 considered? If no, would ISOC consider other bids should the current proposal be rejected?

- How long has Ethos committed to stay invested in PIR? Are there measures in place to ensure continued commitment to the answers above in the event of a resale?

- What changes to ICANN’s agreement with PIR should be made to ensure that dot org is maintained in a manner that serves the public interest, and that ICANN has recourse to act swiftly if it is not?

In terms of process, ICANN needs to approve or reject the transfer of control over the dot org contract. And, presumably, the ISOC board has the power to go back and ask further questions about the deal before it is finalized. We urge these groups to step up to ask questions like the ones above — and not finalize the deal until they and a broad cross section of the dot org community are satisfied with the answers. As they address these questions, we urge them to post their answers publicly.

Also, the state attorneys general of the relevant jurisdictions may be in a position to ask questions about the conversion of PIR into a for profit or about whether ISOCs sale of PIR represents fair market value. If they feel these questions are in their purview, we urge them to share the results of their findings publicly.

One of Mozilla’s principles is the idea that “a balance between commercial profit and public benefit is critical” to maintaining a healthy internet. Yes, much of the internet is and should be commercial — but it is important that significant parts of the internet also remain dedicated to the public interest. The current dot org ecosystem is clearly one of these parts.

The organization that maintains the underpinnings of this ecosystem needs to be a fair and responsible steward. One way to ensure this is to entrust this role to a publicly accountable non-profit, as ICANN did when it picked ISOC as a steward in 2002. While it’s also possible that a for-profit company could effectively play this stewardship role, extra steps would need to be taken to ensure that the company is accountable to dot org stakeholders and not just investors, now and for the long run. It is urgent that we take such steps if the sale of PIR is to go through.

A small postscript: We have sent a letter to ICANN encouraging them to ask the questions above.

The post Questions About .org appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2019/12/03/questions-about-org/

|

|

Support.Mozilla.Org: Updates on Firefox Private Network |

Hi SUMO Community,

Following up on our previous announcement about Firefox Private Network, today marks another milestone for Firefox. We are so excited to expand Firefox Private Network into two different offerings.

Browser-level protection (Extension for any desktop running the Firefox browser)

We are continuing our beta testing of the Firefox Private Network extension that we released earlier this year. The extension hides your Firefox browsing activity and location. This prevents eavesdroppers on public Wi-Fi from spying on the actions you take online by masking your IP address and routing your traffic through our partner’s secure servers. It also protects you from internet service providers collecting or selling data on your browsing activity. And it hides your locations from websites and data collectors that profile you to target ads.

There will be no changes for test pilots who have already started using the extension by logging in with their Firefox account. For those who are not yet using the extension, we invite you to join the Test Pilot program and try it out. When you sign up or log in with a Firefox account and become one of our beta testers, you’ll get 12 hours of protected browsing for free this month. We are continuing to explore the best way to deliver browser-level protection to our users and we welcome your feedback and input each step of the way.

Get extra security by using full-device protection (Windows 10)

If you are looking for unlimited private internet connection that goes beyond the Firefox browser, we are also offering full-device protection with Firefox Private Network. Firefox Private Network full-device protection is a device-level VPN that provides an encrypted tunnel to the web from any software or app on your Windows 10 device.That means your connection is secure and private regardless of which browser or application you are using.

Private Network’s full-device protection is currently available for beta testers in the United States with Windows 10 devices, but it will be available on other platforms soon. You can join the waitlist for the VPN beta here. Selected users will receive an invitation to subscribe for 4.99 USD per month with a U.S. credit card during the beta period.

How can I help as a SUMO contributor?

For the SUMO community, it’s important to understand that we now have two separate products for both services in the Kitsune platform. In addition to that, we also offer another level of support for the paying customers of the Firefox Private Network device-level protection that will be delivered through a ticketing system called Zendesk. As such, both the forums and also Zendesk will be managed by our designated staff member, Brady. However, as with the previous beta phase, we will also welcome any help you may provide for the users in the forum. We are also working on an escalation process from the community to the designated staff member, so expect more updates on that.

We are enthusiastic about this new opportunity and hope that you’ll support us along the way. To get the best out of Firefox experience, sign up for a Firefox Account and join our fight to keep the internet open and accessible to all!

https://blog.mozilla.org/sumo/2019/12/03/updates-on-firefox-private-network/

|

|

Mozilla Future Releases Blog: Firefox Preview Beta reaches another milestone, with Enhanced Tracking Protection and several intuitive features for ease and convenience |

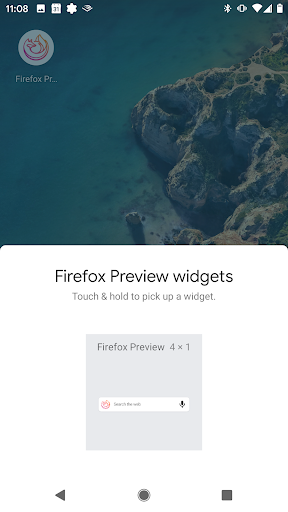

In June we made an announcement, that left us — just like many of our users — particularly excited: we introduced Firefox Preview, a publicly available test version of our upcoming best in class browser for Android that will be fueled by GeckoView. GeckoView is Mozilla’s own high-performance mobile browser engine, which enables us to deliver an even better, faster and more private Firefox to Android device owners. Hundreds of thousands of users have downloaded and tested Firefox Preview since it became available.

Over the past 5 months we’ve been working diligently on improvements to the app. We’ve been listening closely to user feedback and are basing app development on users’ requests and needs; one very recent example is our support for extensions through the WebExtensions API. We will still continue to test Firefox Preview Beta and we’re expecting to launch as a final product in the first half of 2020. Today, we want to provide an update on our progress, and share some of the amazing new features we’ve added to Firefox Preview since the beta release of 1.0.

Please note: The rollout of Firefox Preview Beta 3.0 is currently delayed. The newest features, such as Site Protections, will be made available within the next couple of days. Thanks for your patience.

Browse the web conveniently on mobile with privacy by default

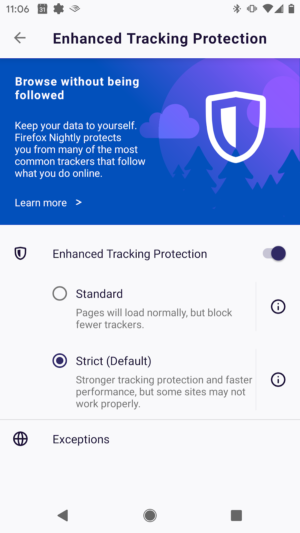

At Firefox, we foster user choice and individual decision making. However, we’ve noticed the massive change the internet economy has undergone over the last couple of years. This transformation has distorted the value exchange between online businesses, the ad industry in particular, and users. It is no longer transparent and consumers are being taken advantage of more and more. We want a better web for people. One that puts users first while still being fast, performant and, above all, private and secure. Still, we can’t expect every user to become an expert on these topics in order to protect themselves. That’s why we’re now making next-level privacy protections the default instead of an option for only the tech-savvy.

This is a guiding principle for the whole Firefox product family and it’s why we’re now taking Firefox Preview to the next level by equipping it with Enhanced Tracking Protection, an innovative technology we first introduced in Firefox for desktop earlier this year, and have been improving ever since. Enhanced Tracking Protection is our approach to put users back in control of their online life by stopping third-party tracking cookies from following them around on the web.