Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Mozilla Privacy Blog: Disconnecting the Connected: How Regulatory and Tax Treatment of Over-the-Top-Services in Africa Creates Barriers for Internet Access. |

Mozilla and the African Union Commission (AUC) released a new study examining the misconceptions, challenges and real-life impact of additional taxes on Over the Top Services (OTTs) imposed by governments across the African continent. The Regulatory Treatment of OTTs in Africa study found that these taxation regimes – often imposed without public consultation and impact assessments – have increased barriers to access, pushed people offline, and limited access to information, and access to services. The study conducted the analysis based on the available evidence and a select number of case studies.

These regressive regulatory measures are taking place as governments rush to introduce digital transformation initiatives, and instead of focusing on how to connect more people to the internet, the region is building barriers that keep them off it.

The study examined the 2018 Ugandan government excise duties which included a mobile money tax of 1% on the transaction value of payments, transfers and withdrawals increasing mobile money fees from 10% to 15% and a new levy on more than 60 online platforms, including Facebook, WhatsApp, and Twitter that amounted to 200 Ugandan Shillings ($0.05) per day. The impact was immediate: the estimated number of internet users in Uganda dropped by nearly 30% between March and September 2018. But the impact is far wider than just the number of lost internet users. An initial estimate in August 2018 was that Uganda had forgone 2.8% in economic growth and 400 billion Ugandan shillings in taxes.

These types of sector-specific taxes pose a considerable threat to internet access and affordability for all users, but especially low income and marginalised people. Internet costs in Uganda are already prohibitively high. Uganda’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita per day, is currently at 7,000 Ugandan shillings ($1.90), and many live off less. Paying 1,000 Ugandan shillings per day for internet data of 50 megabytes and an additional 200 shillings tax is a major challenge. 200 Ugandan shillings ($0.05), is a kilogram of maize in Uganda.

The study further dives into the misconceptions that have contributed to the rise of these types of taxes across the region. The fundamental misunderstanding of the impact of social media on the Internet value chain, and the lack of a clear definition of OTTs has made evidence-based discussions about the impact of OTTs difficult. As a result of these misconceptions, regulatory interventions have used unsuitable tools and have been carried out by the wrong organisations.

Moctar Yedaly, Head of Information Society Division of the African Union Commission (AUC) noted that this study is “a good starting point for understanding the nuances of the impact of OTTs on the ICT ecosystem. We hope that it will lead to regional discussions that would consider more progressive and productive digital taxation models, appropriate policies and regulatory frameworks.”

Finally, the study proposes best practices to help governments create an efficient taxation system while balancing the objectives of collecting taxes, and economic growth, job creation and inclusion of the poor into the information society.

Mozilla and the African Union Commission will continue to engage and support regional discussions, including policy and regulatory efforts, in line with the “Specialized Technical Committee on Communications and Information Technologies (STC-CICT) 3, 2019 declaration, which calls on the AUC to “develop guidelines on Privacy and Over The Top Services in collaboration with relevant institutions and submit the guidelines to the STC-CICT 4 in 2021”.

The post Disconnecting the Connected: How Regulatory and Tax Treatment of Over-the-Top-Services in Africa Creates Barriers for Internet Access. appeared first on Open Policy & Advocacy.

|

|

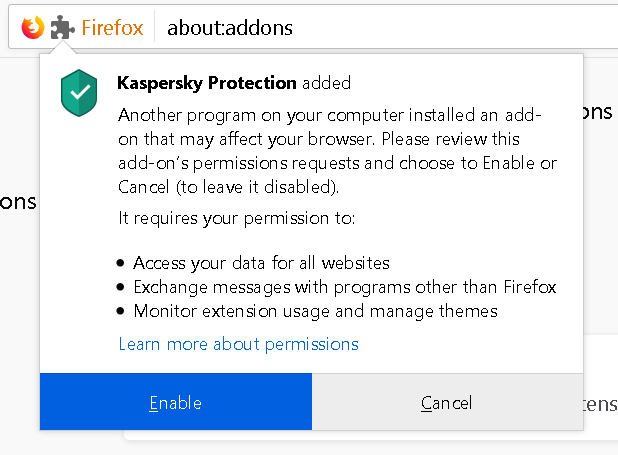

Wladimir Palant: Kaspersky: The art of keeping your keys under the door mat |

Kaspersky’s web protection feature will block ads and trackers, warn you about malicious search results and much more. The complication here: this functionality runs in the browser and needs to communicate with the main application. For this communication to be secure, an important question had to be answered: under which doormat does one put the keys to the kingdom?

Note: Lots of technical details ahead. If you only want a high-level summary, there is one here.

This post sums up five vulnerabilities that I reported to Kaspersky. It is already more than enough ground to cover, so I had to leave unrelated vulnerabilities out. But don’t despair, there is a separate blog post discussing those.

Summary of the findings

In December 2018 I could prove that websites can hijack the communication between Kaspersky browser scripts and their main application in all possible configurations. This allowed websites to manipulate the application in a number of ways, including disabling ad blocking and tracking protection functionality.

Kaspersky reported these issues to be resolved as of July 2019. Yet further investigation revealed that merely the more powerful API calls have been restricted, the bulk of them still being accessible to any website. Worse yet, the new version leaked a considerable amount of data about user’s system, including a unique identifier of the Kaspersky installation. It also introduced an issue which allowed any website to trigger a crash in the application, leaving the user without antivirus protection.

Why is it so complicated?

Antivirus software will usually implement web protection via a browser extension. This makes communication with the main application easy: browser extensions can use native messaging which is trivial to secure. There are built-in security precautions, with the application specifying which browser extensions are allowed to connect to it.

But browser extensions are not the only environment to consider here. If the user declines installing their browser extension, Kaspersky software doesn’t simply give up. Instead, it will inject the necessary scripts into all web pages directly. This works even on HTTPS sites because, as we’ve seen earlier, Kaspersky will break up HTTPS connections in order to manipulate all websites.

In addition, there is the Internet Explorer add-on which is rather special. With Internet Explorer not providing proper extension APIs, that add-on is essentially limited to injecting scripts into web pages. While this doesn’t require manipulating the source code of web pages, the scripts still execute in the context of these pages and without any special privileges.

So it seems that the goal was to provide a uniform way for these three environments to communicate with the Kaspersky application. Yet in two of these environments Kaspersky’s scripts have exactly the same privileges as the web pages that they have been injected into. How does one keep websites from connecting to the application using the same approach? Now you can hopefully see how this task is challenging to say the least.

Kaspersky’s solution

Kaspersky developers obviously came up with a solution, or I wouldn’t be writing this now. They decided to share a secret between application and the scripts (called “signature” in their code). This secret value has to be provided when establishing a connection, and the local server will only respond when receiving the correct value.

How do extensions and scripts know what the secret is? Chrome and Firefox extensions use native messaging to retrieve it. As for the Internet Explorer extension and scripts that are injected directly into web pages, here it becomes part of the script’s source code. And since websites cannot download that source code (forbidden by same-origin policy), they cannot read out the secret. At least in theory.

Extracting the secret

When I looked into Kaspersky Internet Security 2019 in December last year, their web integration code was leaking the secret in all environments (CVE-2019-15685). It didn’t matter which browser you used, it didn’t matter whether you had browser extensions installed or not, every website could extract the secret necessary to communicate with the main Kaspersky application.

From injected scripts

As mentioned earlier, without a browser extension Kaspersky software will inject its scripts directly into web pages. Now JavaScript is a highly dynamic execution environment, it can be manipulated almost arbitrarily. For example, a website could replace the WebSocket object by its own and watch the script establish the connection to the local server. Of course, Kaspersky developers have thought of this scenario, so they made sure their script runs before any of the website scripts do. It will also make a copy of the WebSocket object and only use that copy then.

Yet this approach is far from being watertight. For example, the website can simply make sure that the same script executes again, this time in a manipulated environment. It needs to know the script URL for that, but it can download itself and extract the script URL from the response. Here is how I’ve done it:

fetch(location.href).then(response => response.text()).then(text =>

{

let match = /]*src="([^"]+kaspersky[^"]+\/main.js)"/.exec(text);

if (!match)

return;

let origWebSocket = WebSocket;

WebSocket = function(url)

{

let prefix = url.replace(/(-labs\.com\/).*/, "$1");

let signature = /-labs\.com\/([^\/]+)/.exec(url)[1];

alert(`Kaspersky API available under ${prefix}, signature is ${signature}`);

};

WebSocket.prototype = origWebSocket.prototype;

let script = document.createElement("script");

script.src = match[1];

document.body.appendChild(script);

});

From Internet Explorer extension

The Internet Explorer extension puts the bar slightly higher. While the scripts here also run in an environment that can be manipulated by the website, their execution is triggered directly by the extension. So there is no script URL that the website can find and execute again.

On the other hand, the script doesn’t keep a copy of every function it uses. For example, String.prototype.indexOf() will be called without making sure that it hasn’t been manipulated. No, this function doesn’t get to see any secrets. But, as it turns out, the function calling it gets the KasperskyLabs namespace passed as first parameter which is where all the important info is stored.

let origIndexOf = String.prototype.indexOf;

String.prototype.indexOf = function(...args)

{

let ns = arguments.callee.caller.arguments[0];

if (ns && ns.SIGNATURE)

alert(`Kaspersky API available under ${ns.PREFIX}, signature is ${ns.SIGNATURE}`);

return origIndexOf.apply(this, args);

};

From Chrome and Firefox extensions

Finally, there are Chrome and Firefox extensions. Unlike with the other scenarios, the content scripts here execute in an independent environment which cannot be manipulated by websites. So these don’t need to do anything in order to avoid leaking sensitive data, they merely shouldn’t be actively sending it to web pages. And you already know how this turns out: the Chrome and Firefox extensions leak API access as well.

The attack here abuses a flaw in the way content scripts communicate with frames they inject into pages. The URL Advisor frame is easiest to trigger programmatically, so this attack has to be launched from an HTTPS website with a host name like www.google.malicious.com. The host name starting with www.google. makes sure that URL Advisor is enabled and considers the following HTML code a search result:

<h3 class="r"><a href="https://example.com/">safespan>a>span>h3>URL Advisor will add an image next to that link indicating that it is safe. When the mouse is moved over that image a frame will open with additional details.

And that frame will receive some data to initialize itself, including a commandUrl value which is (you guessed it) the way to access Kaspersky API. Rather than using the extension-specific APIs to communicate with the frame, Kaspersky developers took a shortcut:

function SendToFrame(args)

{

m_balloon.contentWindow.postMessage(ns.JSONStringify(args), "*");

}

I’ll refer to what MDN has to say about using window.postMessage in extensions, particularly about using “*” as the second parameter here:

Web or content scripts can use

window.postMessagewith atargetOriginof"*"to broadcast to every listener, but this is discouraged, since an extension cannot be certain the origin of such messages, and other listeners (including those you do not control) can listen in.

And that’s exactly it – even though this frame was created by extension’s content script, there is no guarantee that it still contains a page belonging to the extension. A malicious webpage can detect the frame being created and replace its contents, which allows it to listen in on any messages sent to this frame. And frame creation is trivial to trigger programmatically with a fake mouseover event.

let onMessage = function(event)

{

alert(`Kaspersky API available under ${JSON.parse(event.data).commandUrl}`);

};

let frameSource = `https://palant.de/2019/11/25/kaspersky-the-art-of-keeping-your-keys-under-the-door-mat/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Mozilla and BMZ Announce Cooperation to Open Up Voice Technology for African Languages |

Mozilla and the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) to jointly build new alliance to foster open voice data and technology in Africa and beyond

Berlin – 25 November 2019. Today, Mozilla and the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) have announced to join forces in the collection of open speech data in local languages, as well as the development of local innovation ecosystems for voice-enabled products and technologies. The initiative builds on the pilot project, which our Open Innovation team and the Machine Learning Group started together with the organization “Digital Umuganda” earlier this year. The Rwandan start-up collects language data in Kinyarwanda, an African language spoken by over 12 million people. Further languages in Africa and Asia are going to be added.

Kelly Davis, Head of Mozilla’s Machine Learning Group, explaining the design and technology behind Deep Speech and Common Voice at a Hackathon in Kigali, February 2019.

Mozilla’s projects Common Voice and Deep Speech will be the heart of the joint initiative, which aims at collecting diverse voice data and opening up a common, public database. Mozilla and the BMZ are planning to partner and collaborate with African start-ups, which need respective training data in order to develop locally suitable, voice-enabled products or technologies that are relevant to their Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Mozilla and the BMZ are also inviting like-minded companies and identifying further countries interested in joining their efforts to open up language data.

The German Ministry and Mozilla share a similar vision and work towards the responsible use of automated decision-making and artificial intelligence for sustainable development on scale. Supporting partner countries in reaching the SDGs, today, the BMZ is carrying out more than 470 digitally enhanced projects in over 90 countries around the world. As part of the National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence, the Federal German Government has agreed to support developing countries in building up capacities and knowledge on opportunities and challenges of AI – an area of expertise that the Mozilla Foundation has heavily invested in with their work on trustworthy AI.

“Artificial Intelligence is changing and shaping our societies globally. It is critical that these technologies are both trustworthy and truly serve everyone. And that means they need to be developed with local needs and expertise in mind, diverse, decentralized, and not driven by monopolies,” says Mark Surman, Executive Director of the Mozilla Foundation.

“Innovating in AI poses complex technological, regulatory and ethical challenges. This is why I am very pleased to see multiple teams within Mozilla working together in this promising cooperation with the BMZ, building on our shared visions and objectives for a positive digital future,” adds Katharina Borchert, Chief Open Innovation Officer of the Mozilla Corporation.

The cooperation was announced at Internet Governance Forum (IGF) in Berlin and will be part of the BMZ initiative “Artificial Intelligence for All: FAIR FORWARD”. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed at Mozilla’s headquarters in Mountain View on November 14.

From left to right: Bj"orn Richter, Head of Digital Development Sector Program, GIZ, Dr. Andreas Foerster, Head of Division Digital Technologies in Development Cooperation, BMZ, Katharina Borchert, Chief Open Innovation Officer, Mozilla, Ashley Boyd, VP, Advocacy Mozilla Foundation, and Udbhav Tiwari, Public Policy Advisor, Mozilla

Mozilla believes that the internet is a global public resource that must remain open and accessible for all people, no matter where they are and which language they speak. With projects such as Common Voice and Deep Speech, Mozilla’s Machine Learning Group is working on advancing and democratizing voice recognition technology on the web.

Useful Links:

- Mozilla Medium Blog Post: Sustainable tech development needs local solutions: Voice tech ideation in Kigali

- Mozilla Foundation: Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence

- About Common Voice

- About Deep Speech

- “Demand Better Of The Internet”: Mozilla at Internet Governance Forum Berlin

The post Mozilla and BMZ Announce Cooperation to Open Up Voice Technology for African Languages appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: And now for something completely different: An Outbound Notebook resurrected |

The 68K laptop manufacturers got around Apple's (later well-founded) clone phobia by importing various components from functioning Macs sold at retail or licensing the chips; some required lobotomizing an otherwise functional machine for its ROMs or even its entire logic board, though at these machines' cheaper price point it was probably still worth it. The big three companies in this particular market were Colby, Dynamac and Outbound. Colby made the WalkMac, which was smaller than the Portable but not much lighter, and required either an SE or SE/30 motherboard. Still, it sold well enough for Sony to threaten to sue them over the Walkman trademark and for Chuck Colby to even develop a tablet version based on the Mac Classic. Dynamac's two models used Mac Plus motherboards (which Apple would only sell to them as entire units, requiring Dynamac to pay for and dispose of the screens and cases they never used), but the EL variant was especially noteworthy for its distinctive 9" amber electroluminescent display.

However, my personal favourite was Outbound. The sprightly kangaroo logo on the case and on the boot screen made people think it was an Australian company (they were actually headquartered in Colorado), including my subsequently disappointed Aussie wife when I landed one for my collection. Outbound distinguished themselves in this market by developing their own logic boards and hardware and only requiring the ROMs from a donor Mac (usually an SE or Plus). Their first was the 1989 Outbound Laptop, which was a briefcase portable not unlike the Compaq Portables of the time, and running at a then-impressive 15MHz. The keyboard connected by infrared, which causes a little PTSD in me because I remember how hideous the IBM PCjr's infrared keyboard was. However, the pointing device was a "trackbar" (trademarked as "Isopoint"), a unique rolling rod that rolled forward and back and side to side. You just put your finger on it and rolled or slid the rod to move the pointer. Besides the obvious space savings, using it was effortless and simple; even at its side extents the pointer would still move if you pushed the bar in the right direction. The Outbound Laptop also let you plug it back into the donor Mac to use that Mac with its ROMs in the Outbound, something they called "hive mode." Best of all, it ran on ordinary VHS camcorder batteries, which you can still find today, and although it was a bit bulky it was about half the weight of the Mac Portable. At a time when the Portable sold for around $6500 it was just $3995.

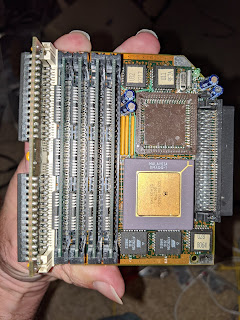

In 1991 Outbound negotiated a deal with Apple to actually get ROMs from them without having to sacrifice another Mac in the process. They used these to construct the Outbound Notebook, which of the two (today rather rare) Outbound machines is easily the more commonly found. The first model 2000 used the same 68000 as the Laptop, boosting it to 20MHz, but the 2030 series moved to the 68030 and ran up to 40MHz. These could even take a 68882 FPU, though they were still limited to 4MB RAM like the Laptop (anything more was turned into a "Silicon" RAM disk supported by an included CDEV). They featured a very nice keyboard and the same innovative trackbar, also took VHS camcorder batteries, and folded to a very trim letter size dimension (about 2" thick) weighing just over six pounds. Thanks to its modular construction it could even be upgraded: the RAM was ordinary 30-pin SIMMs attached to a removable CPU daughtercard where the ROMs, FPU and main CPU connected, and the 2.5" IDE hard drive could also be easily removed, though Outbound put a warranty sticker on it to discourage third-party replacements. For desktop use it had ADB and the $949 Outbound Outrigger monitor plugged into the SCSI port to provide an external display (yes, there were SCSI video devices).

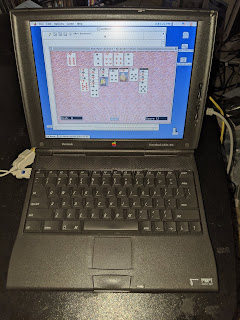

Unlike the other Mac clones, the Outbound Notebook was a serious threat to Apple's portable line at the time. Even though the contemporary PowerBook 100 was rather cheaper ($2300 vs the 40MHz 2030V at $3500) and could take up to 8MB of RAM, it was still the 16MHz 68000 of the Portable era because it was, in fact, simply a miniaturized Mac Portable. Only the simultaneously-introduced PowerBook 170 was anywhere near the same performance ballpark (25MHz '030) as the Notebook, and it was $4600. Apple decided to adopt a contractual solution: while the agreement compelled Apple to still offer SE ROMs to Outbound, they were not similarly obligated to sell ROMs from any later model, and thus they refused and in doing so put an end to the development of a successor. Deprived of subsequent products, Outbound went out of business by the end of 1992, leaving the machines eternally stuck at 7.1.

A couple years ago I picked up a complete 33MHz '030 Outbound Notebook system from a sale, even coming with a small dot matrix printer and the official Outbound car charger (!). Some of you at the Vintage Computer Festival 2017 saw this machine as a terminal for my Apple Network Server 500. It was a bit yellowed and had been clearly heavily used, but worked pretty well right up until it didn't (eventually it went to a garbage screen and wouldn't enter POST). I put it back in the closet for a few months in Odinsleep until an "untested" unit showed up on eBay a couple weeks ago. Now, keep in mind that "untested" is eBay-speak for "it's not working but I'm going to pretend I don't know," so I was pretty sure it was defective, but the case was in nice condition and I figured I could probably pull a few parts off it to try. Indeed, although the kangaroo screen came up, the hard drive started making warbling noises and the machine froze before even getting to the Happy Mac. I put in the hard disk from my dead unit and it didn't do any better, so I swapped the CPU cards as well and ... it booted!

At 33MHz System 7.1 flies, and it has Connectix Compact Virtual (the direct ancestor of RAM Doubler), which at the cost of disabling the Silicon Disk gives me a 16MB addressing space. At some point I'll get around to configuring it for SCSI Ethernet, another fun thing you can do over SCSI that people have forgotten about.

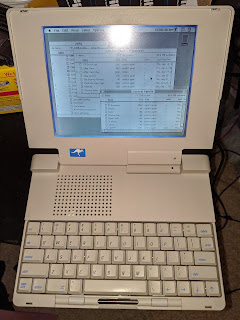

Besides the case, floppy drive and trackbar, the keyboard was also in excellent condition. Let's compare it with what I think is the best keyboard on any Apple laptop past or present, the PowerBook 1400:

This is my personal PowerBook 1400 workhorse which still sees occasional use for classic software. The 1400 was my first Mac laptop, so I'm rather fond of them, and I have a stack of them for spare parts including my original 117cs. This one is almost maximally upgraded, too: it has a Sonnet 466MHz G3, 64MB of RAM, a 4GB IDE drive, Ethernet and modem PCMCIA cards and the Apple 8-bit video card. All it needs is a 16-bit video card and the solar cover (it just has the interchangeable inserts), and it would be the envy of all who behold it.

The 1400 has the keyboard against which all Mac laptops are measured because of its firmness, key travel and pre-scissor construction. It isn't quite as long travel as the IBM ThinkPads of the era, but it easily exceeds any other Apple laptop keyboard then or now, and is highly reliable and easily replaced if necessary (mine has never been necessary). The Outbound's keyboard is a bit stiff by comparison but has decent travel and is less mushy than my other 68K PowerBooks (or for that matter even my iBook G4). While the Portable's keyboard is nice and clicky, it's practically a desktop keyboard, so it's cheating. Score another one for the clone.

For that matter, the 1400 and the Outbound have another thing in common: surprising modularity. Like the Outbound, the 1400's CPU is on a removable daughtercard behind just a couple screws, and the hard disk and RAM can be upgraded easily (though the 1400's wonky stacked RAM system can sometimes be mechanically fraught with peril). It's just a shame it has a custom battery instead of an off-the-shelf one, but that's Apple for you. Neither of them have an easily accessed logic board but that's hardly unusual for laptops. I'm just glad the logic board on this unit was working, because it's nice to have the Outbound revived again for more good times. It's a great historical reminder that sometimes the best Macintoshes didn't come from Cupertino.

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2019/11/and-now-for-something-completely.html

|

|

Chris H-C: This Week in Glean: Glean in Private |

(“This Week in Glean” is a series of blog posts that the Glean Team at Mozilla is using to try to communicate better about our work. They could be release notes, documentation, hopes, dreams, or whatever: so long as it is inspired by Glean.)

In the Kotlin implementation of the Glean SDK we have a glean.private package. (( Ideally anything that was actually private in the Glean SDK would actually _be_ private and inaccessible, but in order to support our SDK magic (okay, so that the SDK could work properly by generating the Specific Metrics API in subcomponents) we needed something public that we just didn’t want anyone to use. )) For a little while this week it looked like the use of the Java keyword private in the name was going to be problematic. Here are some of the alternatives we came up with:

glean.pvtglean.privatglean.p.r.i.v.a.t.eglean.thisIsntForYouDontUseItglean.turn_off_all_security_so_that_viruses_can_take_over_this_computerglean.chutten.says.noglean.using.this.makes.janerik.weepglean.dont.use.or.md.BOOMglean.corporal– Likeglean.privatebut with a promotion

Fortunately (or unfortunately) :mdboom (whom I might have to start calling Dr. Boom) came up with a way to make it work with the package private intact, so we’ll never know which one we would’ve gone with.

Alas.

I guess I’ll just have to console myself with the knowledge that we’ve deployed this fix to Fenix, Python bindings are becoming a reality, and the first code supporting the FOGotype might be landing in mozilla-central. (More to come on all of that, later)

:chutten

https://chuttenblog.wordpress.com/2019/11/22/this-week-in-glean-glean-in-private/

|

|

Marco Zehe: My extended advent calendar |

This year, I have a special treat for my readers. On Monday, November 25, at 12 PM UTC, I will start a 30 day series about everything and anything. Could be an accessibility tip, an how-to about using a feature in an app I use frequently, some personal opinion on something, a link to something great I came across on the web… I am totally not certain yet. I have ideas about some things I want to blog about, but by far not 30 of them yet.

Are you as excited about where this 30 day journey will take us as I am? Well then feel free to join me! You can like this blog in the section at the bottom, follow the RSS feed, follow my Twitter or Mastodon timelines, or like my shiny new Facebook page for the blog. The new posts will appear every day at 12 PM UTC. For those in Europe and Africa this is great, for the U.S. and other parts of the north, central, and south American content it’s earlier, and for those in Asia and Australia it’s late in the day.

I look forward to your comments about what I’ll be posting! Let’s all have some end of year fun together!

https://marcozehe.de/2019/11/22/my-extended-advent-calendar/

|

|

Karl Dubost: Week notes - 2019 w47 - worklog |

Week Notes?

Week Notes. I'm not sure I will be able to commit to this. But they have a bit of revival around my blogging reading echo chamber. Per revival, I mean I see them again.

The Open Data Institute just started one with a round about them. I subscribed again to the feed of Brian Suda and his own week notes. Alice Bartlett has also a very cool personal, down to earth and simple summary of her week. I love that she calls them weaknotes She's on week 63 by now.

So these will not be personal but more covering a bit of the things I (we?) do, learn, fail about webcompat. The only way to do that is to write down properly things. The possible issues: redundancy in writing things elsewhere, the fatigue associated with the regularity. I did a stretch of worklogs in the past.

Bugs

- Apple is using HLS for their videos. This is only implemented in Safari, but still this is working in Chrome, because of

HLS.js. But this library fails in Firefox because this is using RegExp named groups, which are not yet implemented. - Second bug this week showing serious performance issue when the

blurfilter is applied to a large context in the page. - There was an issue about the image viewer on Wikipedia, so I ran

mozregressionand found this changelog. Gecko 3 months made history navigation asynchronous. Kohei Yoshino had already written about it in his excellent Firefox Site Compatibility notes. wikimedia is aware of it. - Another regression related to Make CSP frame-ancestors work with fission enabled

- An additional

inputevent is fired aftercompositionend. It probably should not and that might create a webcompat issue. - There are still issues and differences in the Quirks mode. In this issue, the top relative positioning is not handled properly in quirks mode, it was closed as a duplicate of this previously reported bug.

- missing images are not rendered the same in Chrome, Safari and Firefox. I created tests and I need to file bugs at the appropriate places.

data:text/html,Update: bugs already exists, see the comment by Emilio. - a code using

Event.path(only in Blink) instead ofEvent.composedPath. I wonder if it's a recurrent issue. So there was an issue to drop it on Blink on July 2017. And it was not because it had 2.19% usage on Chromium. And this is even worse now… it has above 15% of usage. WebKit hadEvent.deepPathin the past, but it was renamed ascomposedPath.

Firefox Usage Counters

I need to better understand how counters are working inside Firefox so the numbers become more meaningful. And probably it would be good to understand how they operate at Chrome too. How the counter works when a property is used inside a condition. For example in JavaScript with a construct like:

var mypath = event.path || event.composedPath()

These are probably questions for Boris Bzarsky. Maybe a presentation at All Hands Berlin would be cool on the topic.

- What is happening if the browser implements both, how are they counted?

- What is happening if the browser implements one of these, how are they counted?

- Is the order matters for the counter?

- What are the induced differences if the counter is tracking only one of the property and not the two?

- Can a counter track something which is in the source code but not implemented in the engine. For instance, tracking

event.pathwhich is undefined.

Python tests

We currently do AB testing for webcompat.com for a new form with the goal to improve the quality of the bugs reported. The development has not been an entirely smooth road, and there are still a lot of things to fix, and particulary the missing tests. Our objective is that if the AB testing experiment is successful. We will be rewriting properly the code, and more specifically the tests. So instead of fixing the code, I was thinking that we could just add the tests, so we have a solid base when it's time for rewriting. We'll see. Then Mike was worried that we would break continuous integration. We use nose for running our unittest tests. There is a plugin in nose for creating groups of tests by setting an attr.

from nose.plugins.attrib import attr @attr(form='wizard') class WizardFormTest: def test_exclusive_wizard(self): pass

So we could probably deactivate these specific tests. So this is something to explore.

Webcompat dev

- Discussions with Kate about DB migrations.

- Trying to understand what GitHub really does with linked images, because it might have consequences for our own images hosting.

- Making a local prototype of image upload with the Bottle framework. So I can think differently about it. Bottle is super nice for quick prototyping/thinking. That looks doable. In the end it will be probably done with Flask. It helped identified some issues and some cool things we do.

Writings

- Wrote a blog post about my talk at Mozilla Dev Roadshow in Asia.

- Some thoughts on separating the images upload on webcompat.com from the rest of the app.

Reading

- I have the feeling I could write a counterpart for this blog post about work commuting. There's probably something about work and the circumstances of your country.

- This blog post was followed by a series of internal discussions on the nature of commuting, the reason to commute or not, etc. As usual, a lot of things need to be unpacked when we talk about commuting.

- Impressive and interesting to look at the differences.

from hackerrank

from hackerrank

System abuse? or goofing

- A user reported two invalid bugs and deleted his accounts. It's always for me a surprise when people try to abuse a system which has no power.

Some notes about the week notes

- Should adding pieces be about a linear timeline of events when they happen OR should it be about categories like I did above?

- Was it too long? Oversharing? All of these are notes taken on the last 5 days. And I'm surprised by the amount.

- My work is not linear on one task, which means updates to many tasks are happening in a couple of hours or days.

Otsukare!

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: TenFourFox FPR17b1 available |

This release fixes the "infinite loop" issue on Github with a trivial "hack" mitigation. This mitigation makes JavaScript slightly faster as a side-effect but it's because it relaxes some syntax constraints in the runtime, so I don't consider this a win really. It also gets rid of some debug-specific functions that are web-observable and clashed on a few pages, an error Firefox corrected some time ago but missed my notice. Additionally, since 68ESR newly adds the ability to generate and click on links without embedding them in the DOM, I backported that patch so that we can do that now too (a 4-year-old bug only recently addressed in Firefox 70). Apparently this functionality is required for certain sites' download features and evidently this was important enough to merit putting in an extended support release, so we will follow suit.

I also did an update to cookie security, with more to come, and cleared my backlog of some old performance patches I had been meaning to backport. The most important of these substantially reduces the amount of junk strings JavaScript has hanging around, which in turn reduces memory pressure (important on our 32-bit systems) and garbage collection frequency. Another enables a fast path for layout frames with no properties so we don't have to check the hash tables as frequently.

By user request, this version of TenFourFox also restores the old general.useragent.override.* site-specific override pref feature. This was removed in bug 896114 for performance reasons and we certainly don't need anything that makes the browser any slower, so instead of just turning it back on I also took the incomplete patch in that bug as well and fixed and finished it. This means, in the default state with no site-specific overrides, there is no penalty. This is the only officially supported state. I do not have any plans to expose this feature to the UI because I think it will be troublesome to manage and the impact on loading can be up to 9-10%, so if you choose to use this, you do so at your own risk. I've intentionally declined to mention it in the release notes or to explain any further how this works since only the people who already know what it does and how it operates and most importantly why they need it should be using it. For everyone else, the only official support for changing the user agent remains the global selector in the TenFourFox preference pane (which I might add now allows you to select Firefox 68 if needed). Note that if you change the global setting and have site-specific overrides at the same time, the browser's behaviour becomes "officially undefined." Don't file any bug reports on that, please.

Finally, this release also updates the ATSUI font blacklist and basic adblock database, and has the usual security, certificate, pin, HSTS and TLD updates. Assuming no issues, it will go live on December 2nd or thereabouts.

For FPR18, one thing I would like to improve further is the built-in Reader mode to at least get it more consistent with current Firefox releases. Since layout is rapidly approaching its maximum evolution (as determined by the codebase, the level of work required and my rapidly dissipating free time), the Reader mode is probably the best means for dealing with the (fortunately relatively small) number of sites right now that lay out problematically. There are some other backlogged minor changes I would like to consider for that release as well. However, FPR18 will be parallel with the first of the 4-week cadence Firefox releases and as I have mentioned before I need to consider how sustainable that is with my other workloads, especially as most of the low-hanging fruit has long since been picked.

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2019/11/tenfourfox-feature-parity-release-17.html

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Princesses make terrible passwords |

When the Disney+ streaming service rolled out, millions of people flocked to set up accounts. And within a week, thousands of poor unfortunate souls reported that their Disney passwords were … Read more

The post Princesses make terrible passwords appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Two ways Firefox protects your holiday shopping |

We’re entering another holiday shopping season, and while you’re browsing around on the internet looking for thoughtful presents for friends and loved ones, it’s also a good time to give … Read more

The post Two ways Firefox protects your holiday shopping appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

|

|

Mozilla Localization (L10N): L10n Report: November Edition |

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Firefox Extension Spotlight: Image Search Options |

Let’s say you stumble upon an interesting image on the web and you want to learn more about it, like… where did it come from? Who are the people in … Read more

The post Firefox Extension Spotlight: Image Search Options appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/firefox-extension-image-search-options/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Can Your Holiday Gift Spy on You? |

Mozilla is unveiling its annual holiday ranking of the creepiest and safest connected devices. Our researchers reviewed the security and privacy features and flaws of 76 popular gifts for 2019’s *Privacy Not Included guide

Mozilla today launches the third-annual *Privacy Not Included, a report and shopping guide identifying which connected gadgets and toys are secure and trustworthy — and which aren’t. The goal is two-fold: arm shoppers with the information they need to choose gifts that protect the privacy of their friends and family. And, spur the tech industry to do more to safeguard consumers.

Mozilla researchers reviewed 76 popular connected gifts available for purchase in the United States across six categories: Toys & Games; Smart Home; Entertainment; Wearables; Health & Exercise; and Pets. Researchers combed through privacy policies, sifted through product and app specifications, reached out to companies about their encryption and bug bounty programs, and more. As a result, we can answer questions like: How accessible is the privacy policy, if there is one? Does the product require strong passwords? Does it collect biometric data? And, Are there automatic security updates?

The guide also showcases the Creep-O-Meter, an interactive tool allowing shoppers to rate the creepiness of a product using an emoji sliding scale from “Super Creepy” to “Not Creepy.

Says Ashley Boyd, Mozilla’s Vice President of Advocacy: “This year we found that many of the big tech companies like Apple and Google are doing pretty well at securing their products, and you’ll see that most products in the guide meet our Minimum Security Standards. But don’t let that fool you. Even though devices are secure, we found they are collecting more and more personal information on users, who often don’t have a whole lot of control over that data.”

For the first time ever, this year’s guide is launching alongside new longform research from Mozilla’s Internet Health Report. Two companion articles are debuting alongside the guide and provide additional context and insight into the realm of connected devices: what’s working, what’s not, and how consumers can wrestle back control. The articles include “How Smart Homes Could Be Wiser,” an exploration of why trustworthy connected devices are so scarce, and what consumers can do to remedy this. And “5 key decisions for every smart device,” a look at five key areas manufacturers should address when designing private and secure connected devices.

*Privacy Not Included highlights include:

- 62 products were awarded a badge for meeting the Minimum Security Standards created by Mozilla, Internet Society and Consumer International. To receive a badge, products must: use encryption; have automatic security updates; feature strong password mechanics; manage security vulnerabilities; and offer accessible privacy policies. A star rating near the top of each product page shows how well each product does on the Minimum Security Standards. Products meeting Minimum Security Requirements include: Nintendo Switch, Apple Watch 5, Amazon Fire Kids HD, and Disney Frozen 2 Coding Kit

- Eight products did not meet the Minimum Security Standards: the Ring Video Doorbell, Ring Indoor Cam, Ring Security Cams, Wemo Wifi Smart Dimmer, Artie 3000 Coding Robot, Litter Robot 3 Connect, OurPets SmartScoop Intelligent Litter Box and Petsafe Smart Pet Feeder

- Mozilla was not able to make a conclusive determination whether six products met Minimum Security Standards. This was based on factors like a company not responding to researchers’ inquiries; or if a company’s response conflicted with recent independent security audits or reports from penetration testers. These products are Wagz Serve Smart Feeder, Petzi Treat Cam, Star Wars Boost Droid Commander, Link AKC Smart Collar, PetCube Bites 2, and Instant Pot Smart Wifi

Top trends identified by Mozilla researchers include:

- Good on security, questionable on privacy: Many of the big tech companies like Apple and Google are doing pretty well at securing their products. But even when devices are secure, they can still collect a lot of data about users. This year saw an expansion of smart home ecosystems from big tech companies, allowing companies like Amazon to reach deeper into user’s lives. Customer data is also being used in ways users may not have anticipated, even if it’s stated in the privacy policy. For instance, Ring users may not realize their videos are being used in marketing campaigns and that photos of all visitors are stored on servers.

- Small companies are not doing so well on privacy and security: Smaller companies often do not have the resources to prioritize the privacy and security of their products. Many of the products in the pet category, for example, seem weak on privacy and security. Mozilla could only confirm four of the 13 products meet our Minimum Security Standards. The $500 Litter Robot 3 Connect didn’t even have a privacy policy for the device or the app the device uses. Also, it appears to use the default password “neverscoop” to connect the device to WiFi.

- Privacy policy readability is improving: Companies are making strides in how they present privacy information, with a lot more privacy pages — like those by Roomba and Apple — being written in simple, accessible language and housed in one central place.

- Products are becoming more privacy friendly, but sometimes at a cost to consumers: Sonos removed the microphone for the Sonos One SL to make it more privacy-friendly, while Parrot, which made one of the creepiest products in the 2018 guide, launched the Anafi drone, which met the Minimum Security Standards. However, Parrot left the low end consumer market: the Anafi drone costs $700.

*Privacy Not Included builds on Mozilla’s work to ensure the internet remains open, safe, and accessible to all people. Mozilla’s initiatives include its annual Internet Health Report; its roster of Fellows who develop research, policies, and products around privacy, security, and other internet health issues; and its advocacy campaigns, such as putting public pressure on apps like Snapchat and Instagram to let users know if they are using facial emotion recognition software.

About Mozilla

Mozilla is a nonprofit that believes the internet must always remain a global public resource, open and accessible to all. Its work is guided by the Mozilla Manifesto. The direct work of the Mozilla Foundation focuses on fueling the movement for an open Internet. Mozilla does this by connecting open Internet leaders with each other and by mobilizing grassroots activists around the world. The Foundation is also the sole shareholder in the Mozilla Corporation, the maker of Firefox and other open source tools. Mozilla Corporation functions as a self-sustaining social enterprise — money earned through its products is reinvested into the organization.

The post Can Your Holiday Gift Spy on You? appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2019/11/20/can-your-holiday-gift-spy-on-you/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Multiple-column Layout and column-span in Firefox 71 |

Firefox 71 is an exciting release for anyone who cares about CSS Layout. While I am very excited to have subgrid available in Firefox, there is another property that I’ve been keeping an eye on. Firefox 71 implements column-span from Multiple-column Layout. In this post I’ll explain what it is and a little about the progress of the Multiple-column Layout specification.

Multiple-column Layout, usually referred to as multicol, is a layout method that does something quite different to layout methods such as flexbox and grid. If you have some content marked up and displaying in Normal Flow, and turn that into a multicol container using the column-width or column-count properties, it will display as a set of columns. Unlike Flexbox or Grid however, the content inside the columns flows just as it did in Normal Flow. The difference is that it now flows into a number of anonymous column boxes, much like content in a newspaper.

See the Pen

Columns with multicol by rachelandrew (@rachelandrew)

on CodePen.

Multicol is described as fragmenting the content when it creates these anonymous column boxes to display content. It does not act on the direct children of the multicol container in a flex or grid-like way. In this way it is most similar to the fragmentation that happens when we print a web document, and the content is split between pages. A column-box is essentially the same thing as a page.

What is column-span?

We can use the column-span property to take an element appearing in a column, and cause it to span across all of the columns. This is a pattern common in print design. In the CodePen below I have two such spanning elements:

- The

h1is inside the article as the first child element and is spanning all of the columns. - The

h2is inside the second section, and also spans all of the columns.

See the Pen

Columns with multicol and column-span by rachelandrew (@rachelandrew)

on CodePen.

This example highlights a few things about column-span. Firstly, it is only possible to span all of the columns, or no columns. The allowable values for column-span are all, or none.

Secondly, when a span interrupts the column boxes, we end up with two lines of columns. The columns are created in the inline direction above the spanning element, then they restart below. Content in the columns does not “jump over” the spanning element and continue.

In addition, the h1 is a direct child of the multicol container, however the h2 is not. The h2 is nested inside a section. This demonstrates the fact that items do not need to be a direct child to have column-span applied to them.

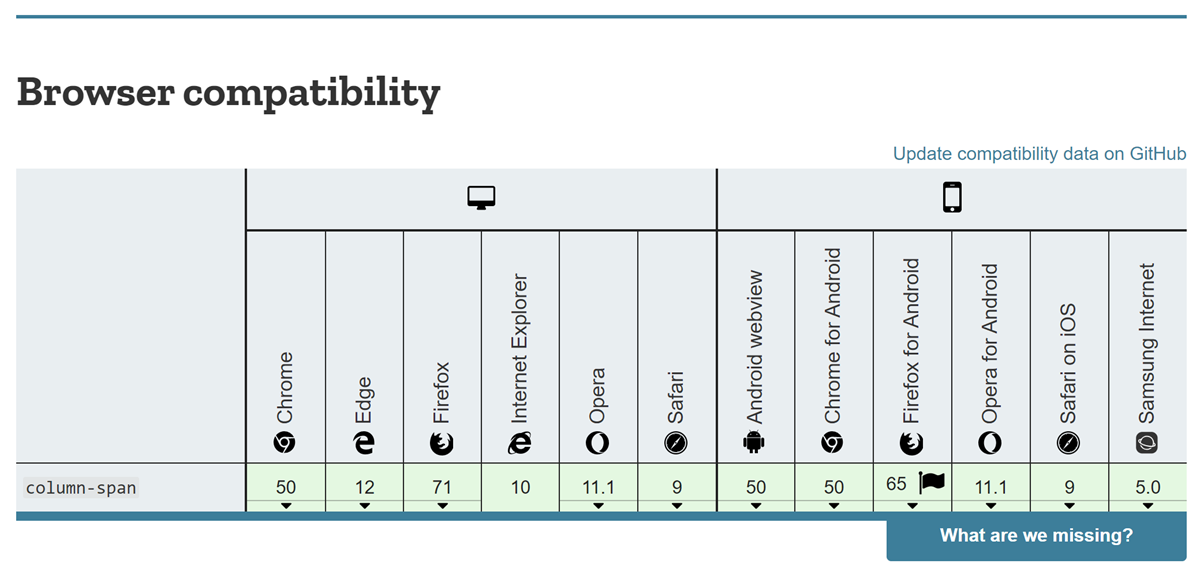

Firefox has now joined other browsers in implementing the column-span property. This means that we have good support for the property across all major browsers, as the Compat data for column-span shows.

The multicol specification

My interest in the implementation of column-span is partly because I am one of the editors of the multicol specification. I volunteered to edit the multicol specification as it had been stalled for some time, with past resolutions by the WG not having been edited into the spec. There were also a number of unresolved issues, many of which were to do with the column-span feature. I started work by digging through the mailing list archives to find these issues and resolutions where we had them. I then began working through them and editing them into the spec.

At the time I started working on the specification it was at Candidate Recommendation (CR) status, which infers that the specification is deemed to be fairly complete. Given the number of issues, the WG decided to return it to Working Draft (WD) status while these issues were resolved.

CSS development needs teamwork between browsers and spec editors

As a spec editor, it’s exciting when features are being implemented, as it helps to progress the spec. CSS is created via an iterative and collaborative process; the CSS WG do not create a complete specification and fling it over the wall at browser engineers. The process involves working on a feature in the WG, which browser engineers try to implement. Questions and problems discovered during that implementation phase are brought back to the working group. The WG then have to decide what to do about such issues, and the spec editor then gets the job of clarifying the spec based on the resolution. The process repeats — each time we tease out issues. Any lack of clarity could cause an interoperability issue if two browsers interpreted the description of the feature in a different way.

Based on the work that Mozilla have been doing to implement column-span, several issues were brought to the CSS WG and discussed in our calls and face-to-face meetings. We’ve been able to make the specification much clearer on a number of issues with column-span and related issues. Therefore, I’m very happy to have a new property implemented across browsers, and also happy to have a more resilient spec! We recently published an updated WD of multicol, which includes many changes made during the time Mozilla were implementing multicol in Firefox.

Other multicol related issues

With the implementation of column-span, multicol will work in much the same way across browsers. We do have an outstanding issue with regards to the column-fill property, which controls how the columns are filled. The default way that multicol fills columns is to try to balance the content, so equal amounts of content end up in each column.

By using the column-fill property, you can change this behavior to fill columns sequentially. This would mean that a multicol container with a height could fill columns to the specified height, potentially leaving empty columns if there was not enough content.

See the Pen

Columns with multicol and column-fill by rachelandrew (@rachelandrew)

on CodePen.

Due to specification ambiguity, Firefox and Chrome do different things if the multicol container does not have a height. Chrome ignores the column-fill property and balances, whereas Firefox fills the first column with all of the content. This is the kind of issue that arises when we have a vague or unclear spec. It’s not a case of a browser “getting things wrong”, or trying to make the lives of web developers hard. It’s what happens when specifications aren’t crystal clear! For anyone interested, the somewhat lengthy issue trying to resolve this is here. Most developers won’t come across this issue in practice. However, if you are seeing differences when using column-fill, it is worth knowing about.

The implementation of column-span is a step towards making multicol robust and useful on the web. To read more about multicol and possible use cases see the Guides to Multicol on MDN, and my article When And How To Use Multiple-column Layout.

The post Multiple-column Layout and column-span in Firefox 71 appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/11/multiple-column-layout-and-column-span-in-firefox-71/

|

|

Karl Dubost: Saving Webcompat images as a microservice |

Update: You may want to fast forward to the latest part… of this blog post. (Head explodes).

Thinking out loud on separating our images into a separate service. The initial goal was to push the images to the cloud, but I think we could probably have a first step. We could keep the images on our server, but instead of the current save, we could send them to another service, let say upload.webcompat.com with a HTTP PUT. And this service would save them locally.

That way it would allow us two things:

- Virtualize the core app on heroku if needed

- Replace when we are ready the microservice by another cloud hosting solution.

All of this is mainly thinking for now.

Anatomy of our environment

config/environment.py defines:

UPLOADS_DEFAULT_DEST = os.environ.get('PROD_UPLOADS_DEFAULT_DEST') UPLOADS_DEFAULT_URL = os.environ.get('PROD_UPLOADS_DEFAULT_URL')

The maximum limit for images is defined in __init__.py

Currently in views.py, there is a route for localhost upload.

# set limit of 5.5MB for file uploads # in practice, this is ~4MB (5.5 / 1.37) # after the data URI is saved to disk app.config['MAX_CONTENT_LENGTH'] = 5.5 * 1024 * 1024

The localhost part would probably not changed much. This is just for reading the images URL.

if app.config['LOCALHOST']: @app.route('/uploads/') def download_file(filename): """Route just for local environments to send uploaded images. In production, nginx handles this without needing to touch the Python app. """ return send_from_directory( app.config['UPLOADS_DEFAULT_DEST'], filename)

then the api for uploads is defined in api/uploads.py

This is where the production route is defined.

@uploads.route('/', methods=['POST']) def upload(): '''Endpoint to upload an image. If the image asset passes validation, it's saved as: UPLOADS_DEFAULT_DEST + /year/month/random-uuid.ext Returns a JSON string that contains the filename and url. ''' … # cut some stuff. try: upload = Upload(imagedata) upload.save() data = { 'filename': upload.get_filename(upload.image_path), 'url': upload.get_url(upload.image_path), 'thumb_url': upload.get_url(upload.thumb_path) } return (json.dumps(data), 201, {'content-type': JSON_MIME}) except (TypeError, IOError): abort(415) except RequestEntityTooLarge: abort(413)

upload.save is basically where we should replace this by an HTTP PUT to a micro service.

What is Amazon S3 doing?

In these musings, I wonder if we could mimick the way Amazon S3 operates at a very high level. No need to replicate everything. We just need to save some bytes into a folder structure.

boto 3 has a documentation for uploading files.

def upload_file(file_name, bucket, object_name=None): """Upload a file to an S3 bucket :param file_name: File to upload :param bucket: Bucket to upload to :param object_name: S3 object name. If not specified then file_name is used :return: True if file was uploaded, else False """ # If S3 object_name was not specified, use file_name if object_name is None: object_name = file_name # Upload the file s3_client = boto3.client('s3') try: response = s3_client.upload_file(file_name, bucket, object_name) except ClientError as e: logging.error(e) return False return True

We could keep the image validation on the size of webcompat.com, but then the naming and checking is done. We can save this to a service the same way aws is doing.

So our priviledged service could accept images and save them locally in the same folder structure a separate flask structure. And later on, we could adjust it to use S3.

Surprise. Surprise.

I just found out that each time you put an image in an issue or a comment. GitHub is making a private copy of this image. Not sure if it's borderline with regards to property.

If you enter:

Then it creates this markup.

<p><a target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer" href="https://camo.githubusercontent.com/a285646de4a7c3b3cdd3e82d599e46607df8d3cc/687474703a2f2f7777772e6c612d6772616e67652e6e65742f323031392f30312f30312f323533352d6d6973657265"><img src="https://camo.githubusercontent.com/a285646de4a7c3b3cdd3e82d599e46607df8d3cc/687474703a2f2f7777772e6c612d6772616e67652e6e65742f323031392f30312f30312f323533352d6d6973657265" alt="I'm root" data-canonical-src="http://www.la-grange.net/2019/01/01/2535-misere" style="max-width:100%;">span>a>span>p>

And we can notice that the img src is pointing to… GitHub?

I checked in my server logs to be sure. And I found…

140.82.115.251 - - [20/Nov/2019:06:44:54 +0000] "GET /2019/01/01/2535-misere HTTP/1.1" 200 62673 "-" "github-camo (876de43e)"

That will seriously challenge the OKR for this quarter.

Update: 2019-11-21 So I tried to decipher what was really happening. It seems GitHub acts as a proxy using camo, but still has a caching system keeping a real copy of the images, instead of just a proxy. And this can become a problem in the context of webcompat.com.

Early on, we had added s3.amazonaws.com to our connect-src since we had uses that were making requests to https://s3.amazonaws.com/github-cloud. However, this effectively opened up our connect-src to any Amazon S3 bucket. We refactored our URL generation and switched all call sites and our connect-src to use https://github-cloud.s3.amazonaws.com to reference our bucket.

GitHub is hosting the images on Amazon S3.

Otsukare!

http://www.otsukare.info/2019/11/20/saving-images-microservices

|

|

Mozilla Security Blog: Updates to the Mozilla Web Security Bounty Program |

Mozilla was one of the first companies to establish a bug bounty program and we continually adjust it so that it stays as relevant now as it always has been. To celebrate the 15 years of the 1.0 release of Firefox, we are making significant enhancements to the web bug bounty program.

Increasing Bounty Payouts

We are doubling all web payouts for critical, core and other Mozilla sites as per the Web and Services Bug Bounty Program page. In addition we are tripling payouts to $15,000 for Remote Code Execution payouts on critical sites!

Adding New Critical Sites to the Program

As we are constantly improving the services behind Firefox, we also need to ensure that sites we consider critical to our mission get the appropriate attention from the security community. Hence we have extended our web bug bounty program by the following sites in the last 6 months:

- Autograph – a cryptographic signature service that signs Mozilla products.

- Lando – Mozilla’s new automatic code-landing service which allows us to easily commit Phabricator revisions to their destination repository.

- Phabricator – a code management tool used for reviewing Firefox code changes.

- Taskcluster the task execution framework that supports Mozilla’s continuous integration and release processes (promoted from core to critical).

Adding New Core Sites to the Program

The sites we consider core to our mission have also been extended to include:

- Firefox Monitor – a site where you can register your email address so that you can be informed if your account details are part of a data breach.

- Localization – a service contributors can use to help localize Mozilla products.

- Payment Subscription – a service that is used as the interface in front of the payment provide (Stripe).

- Firefox Private Network – a site from which you can download a desktop extension that helps secure and protect your connection everywhere you use Firefox.

- Ship It – a system that accepts requests for releases from humans and translates them into information and requests that our Buildbot-based release automation can process.

- Speak To Me – Mozilla’s Speech Recognition API.

The new payouts have already been applied to the most recently reported web bugs.

We hope the new sites and increased payments will encourage you to have another look at our sites and help us keep them safe for everyone who uses the web.

Happy Birthday, Firefox. And happy bug hunting to you all!

The post Updates to the Mozilla Web Security Bounty Program appeared first on Mozilla Security Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/security/2019/11/19/updates-to-the-mozilla-web-security-bounty-program/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Creating UI Extensions for WebThings Gateway |

Version 0.10 of Mozilla’s WebThings Gateway brings support for extension-type add-ons. Released last week, this powerful new capability lets developers modify the user interface (UI) to their liking with JavaScript and CSS.

Although the initial set of extension APIs is fairly minimal, we believe that they will already enable a large amount of functionality. To go along with the UI extensions, developers can also extend the gateway’s REST API with their own handlers, allowing for back-end analytics, for example.

In this post, we’ll walk through a simple example to get you started with building your own extension.

The Basics

If you’re completely new to building add-ons for the WebThings Gateway, there are a couple things you should know.

An add-on is a set of code that runs alongside the gateway. In the case of extensions, the code runs as part of the UI in the browser. Add-ons can provide all sorts of functionality, including support for new devices, the ability to notify users via some outlet, and now, extending the user interface.

Add-ons are packaged up in a specific way and can then be published to the add-on list, so that they can be installed by other users. For best results, developers should abide by these basic guidelines.

Furthermore, add-ons can theoretically be written in any language, as long as they know how to speak to the gateway via IPC (interprocess communication). We provide libraries for Node.js and Python.

The New APIs

There are two new groups of APIs you should know about.

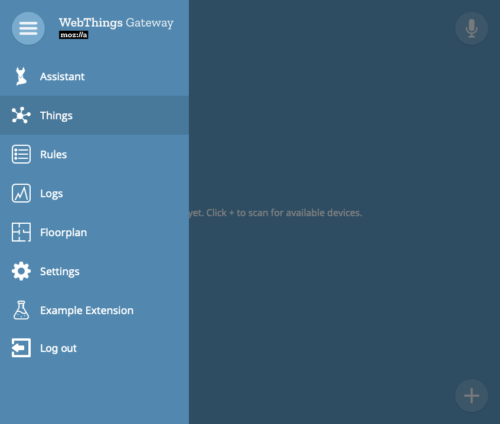

First, the front end APIs. Your extension should extend the Extension class, which is global to the browser window. This gives you access to all of the new APIs. In this 0.10 release, extensions can add new entries to the top-level menu and show and hide top-level buttons. Each extension gets an empty block element that they can draw to as they please, which can be accessed via the menu entry or some other means.

Second, the back end APIs. An add-on can register a new APIHandler. When an authenticated request is made to /extensions//api/*, your API handler will be invoked with request information. It should send back the appropriate response.

Basic Example

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s walk through a simple example. You can find the code for this example on GitHub. Want to see the example in Python, instead of JavaScript? It’s available here.

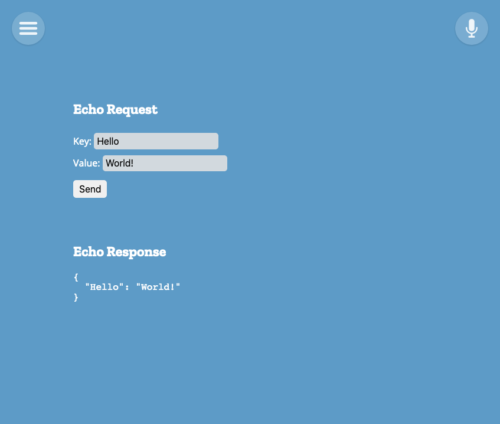

This next example is really basic: create a form, submit the form, and echo the result back as JSON.

Let’s go ahead and create our API handler. For this example, we’ll just echo back what we received.

const {APIHandler, APIResponse} = require('gateway-addon');

const manifest = require('./manifest.json');

/**

* Example API handler.

*/

class ExampleAPIHandler extends APIHandler {

constructor(addonManager) {

super(addonManager, manifest.id);

addonManager.addAPIHandler(this);

}

async handleRequest(request) {

if (request.method !== 'POST' || request.path !== '/example-api') {

return new APIResponse({status: 404});

}

// echo back the body

return new APIResponse({

status: 200,

contentType: 'application/json',

content: JSON.stringify(request.body),

});

}

}

module.exports = ExampleAPIHandler;The gateway-addon library provides nice wrappers for the API requests and responses. You fill in the basics: status code, content type, and content. If there is no content, you can omit those fields.

Now, let’s create a UI that can actually use the new API we’ve just made.

(function() {

class ExampleExtension extends window.Extension {

constructor() {

super('example-extension');

this.addMenuEntry('Example Extension');

this.content = '';

fetch(`/extensions/${this.id}/views/content.html`)

.then((res) => res.text())

.then((text) => {

this.content = text;

})

.catch((e) => console.error('Failed to fetch content:', e));

}

show() {

this.view.innerHTML = this.content;

const key =

document.getElementById('extension-example-extension-form-key');

const value =

document.getElementById('extension-example-extension-form-value');

const submit =

document.getElementById('extension-example-extension-form-submit');

const pre =

document.getElementById('extension-example-extension-response-data');

submit.addEventListener('click', () => {

window.API.postJson(

`/extensions/${this.id}/api/example-api`,

{[key.value]: value.value}

).then((body) => {

pre.innerText = JSON.stringify(body, null, 2);

}).catch((e) => {

pre.innerText = e.toString();

});

});

}

}

new ExampleExtension();

})();The above code does the following things:

- Adds a top-level menu entry for our extension.

- Loads some HTML asynchronously from the server.

- Sets up an event listener for the form to submit it and display the results.

The HTML loaded from the server is not a full document, but rather a snippet, since we’re using it to fill in a tag. You could do all this synchronously within the JavaScript, but it can be nice to keep the view content separate. The manifest for this add-on instructs the gateway which resources to load, and which are allowed to be accessed via the web:

{

"author": "Mozilla IoT",

"content_scripts": [

{

"css": [

"css/extension.css"

],

"js": [

"js/extension.js"

]

}

],

"description": "Example extension add-on for Mozilla WebThings Gateway",

"gateway_specific_settings": {

"webthings": {

"exec": "{nodeLoader} {path}",

"primary_type": "extension",

"strict_max_version": "*",

"strict_min_version": "0.10.0"

}

},

"homepage_url": "https://github.com/mozilla-iot/example-extension",

"id": "example-extension",

"license": "MPL-2.0",

"manifest_version": 1,

"name": "Example Extension",

"short_name": "Example",

"version": "0.0.3",

"web_accessible_resources": [

"css/*.css",

"images/*.svg",

"js/*.js",

"views/*.html"

]

}The content_scripts property of the manifest tells the gateway which CSS and JavaScript files to load into the UI. Meanwhile, the web_accessible_resources tells it which files can be accessed by the extension over HTTP. This format is based on the WebExtension manifest.json format, so if you’ve ever built a browser extension, it may look familiar to you.

As a quick note to developers, this new manifest.json format is required for all add-ons now, as it replaces the old package.json format.

Testing the Add-on

To test, you can do the following on your Raspberry Pi or development machine.

- Clone the repository:

cd ~/.mozilla-iot/addons git clone https://github.com/mozilla-iot/example-extension - Restart the gateway:

sudo systemctl restart mozilla-iot-gateway - Enable the add-on by navigating to Settings -> Add-ons in the UI. Click the Enable button for “Example Extension”. You then need to refresh the page for your extension to show up in the UI, as extensions are loaded when the page first loads.

Wrapping Up

Hopefully this has been helpful. The example itself is not very useful, but it should give you a nice skeleton to start from.

Another possible use case we’ve identified is creating a custom UI for complex devices, where the auto-generated UI is less than ideal. For instance, an adapter add-on could add an alternate UI link which just links to the extension, e.g. /extensions/. When accessed, the UI will bring up the extension’s interface.

If you have more questions, you can always reach out on Discourse, GitHub, or IRC (#iot). We can’t wait to see what you build!

The post Creating UI Extensions for WebThings Gateway appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/11/ui-extensions-webthings-gateway/

|

|

Alessio Placitelli: GeckoView + Glean = Fenix performance metrics |

https://www.a2p.it/wordpress/tech-stuff/mozilla/geckoview-glean-fenix-performance-metrics/

|

|