Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Cameron Kaiser: ICYMI: what's new on Talospace |

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2018/11/icymi-whats-new-on-talospace.html

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: HTTP/3 |

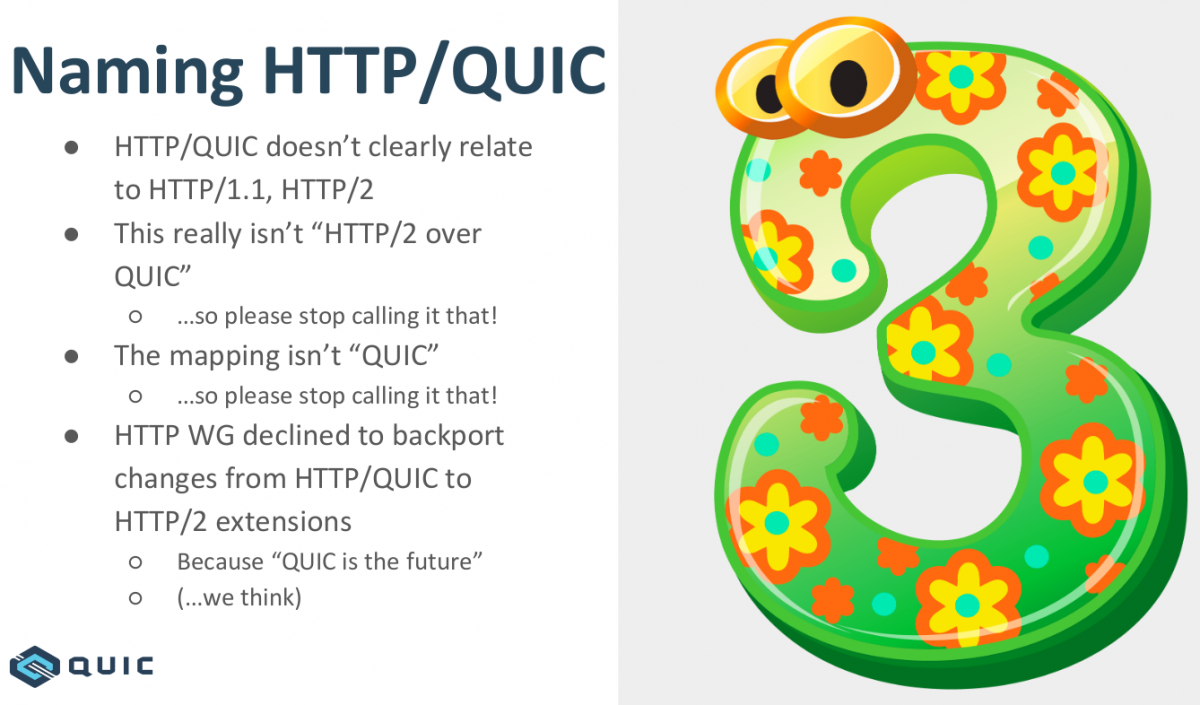

The protocol that's been called HTTP-over-QUIC for quite some time has now changed name and will officially become HTTP/3. This was triggered by this original suggestion by Mark Nottingham.

The QUIC Working Group in the IETF works on creating the QUIC transport protocol. QUIC is a TCP replacement done over UDP. Originally, QUIC was started as an effort by Google and then more of a "HTTP/2-encrypted-over-UDP" protocol.

When the work took off in the IETF to standardize the protocol, it was split up in two layers: the transport and the HTTP parts. The idea being that this transport protocol can be used to transfer other data too and its not just done explicitly for HTTP or HTTP-like protocols. But the name was still QUIC.

People in the community has referred to these different versions of the protocol using informal names such as iQUIC and gQUIC to separate the QUIC protocols from IETF and Google (since they differed quite a lot in the details). The protocol that sends HTTP over "iQUIC" was called "hq" (HTTP-over-QUIC) for a long time.

Mike Bishop scared the room at the QUIC working group meeting in IETF 103 when he presented this slide with what could be thought of almost a logo...

On November 7, 2018 Dmitri of Litespeed announced that they and Facebook had successfully done the first interop ever between two HTTP/3 implementations. Mike Bihop's follow-up presentation in the HTTPbis session on the topic can be seen here. The consensus in the end of that meeting said the new name is HTTP/3!

No more confusion. HTTP/3 is the coming new HTTP version that uses QUIC for transport!

|

|

Niko Matsakis: After NLL: Moving from borrowed data and the sentinel pattern |

|

|

Mike Hoye: The Evolution Of Open |

This started its life as a pair of posts to the Mozilla governance forum, about the mismatch between private communication channels and our principles of open development. It’s a little long-winded, but I think it broadly applies not just to Mozilla but to open source in general. This version of it interleaves those two posts into something I hope is coherent, if kind of rambly. Ultimately the only point I want to make here is that the nature of openness has changed, and while it doesn’t mean we need to abandon the idea as a principle or as a practice, we can’t ignore how much has changed or stay mired in practices born of a world that no longer exists.

If you’re up for the longer argument, well, you can already see the wall of text under this line. Press on, I believe in you.

Even though open source software has essentially declared victory, I think that openness as a practice – not just code you can fork but the transparency and accessibility of the development process – matters more than ever, and is in a pretty precarious position. I worry that if we – the Royal We, I guess – aren’t willing to grow and change our understanding of openness and the practical realities of working in the open, and build tools to help people navigate those realities, that it won’t be long until we’re worse off than we were when this whole free-and-open-source-software idea got started.

To take that a step further: if some of the aspirational goals of openness and open development are the ideas of accessibility and empowerment – that reducing or removing barriers to participation in software development, and granting people more agency over their lives thereby, is self-evidently noble – then I think we need to pull apart the different meanings of the word “open” that we use as if the same word meant all the same things to all the same people. My sense is that a lot of our discussions about openness are anchored in the notion of code as speech, of people’s freedom to move bits around and about the limitations placed on those freedoms, and I don’t think that’s enough.

A lot of us got our start when an internet connection was a novelty, computation was scarce and state was fragile. If you – like me – are a product of this time, “open” as in “open source” is likely to be a core part of your sense of personal safety and agency; you got comfortable digging into code, standing up your own services and managing your own backups pretty early, because that was how you maintained some degree of control over your destiny, how you avoided the indignities of data loss, corporate exploitation and community collapse.

“Open” in this context inextricably ties source control to individual agency. The checks and balances of openness in this context are about standards, data formats, and the ability to export or migrate your data away from sites or services that threaten to go bad or go dark. This view has very little to say – and is often hostile to the idea of – granular access restrictions and the ability to impose them, those being the tools of this worldview’s bad actors.

The blind spots of this worldview are the products of a time where someone on the inside could comfortably pretend that all the other systems that had granted them the freedom to modify this software simply didn’t exist. Those access controls were handled, invisibly, elsewhere; university admission, corporate hiring practices or geography being just a few examples of the many, many barriers between the network and the average person.

And when we’re talking about blind spots and invisible social access controls, of course, what we’re really talking about is privilege. “Working in the open”, in a world where computation was scarce and expensive, meant working in front of an audience that was lucky enough to go to university or college, whose parents could afford a computer at home, who lived somewhere with broadband or had one of the few jobs whose company opened low-numbered ports to the outside world; what it didn’t mean was doxxing, cyberstalking, botnets, gamergaters, weaponized social media tooling, carrier-grade targeted-harassment-as-a-service and state-actor psy-op/disinformation campaigns rolling by like bad weather. The relentless, grinding day-to-day malfeasance that’s the background noise of this grudgefuck of a zeitgeist we’re all stewing in just didn’t inform that worldview, because it didn’t exist.

In contrast, a more recent turn on the notion of openness is one of organizational or community openness; that is, openness viewed through the lens of the accessibility and the experience of participation in the organization itself, rather than unrestricted access to the underlying mechanisms. Put another way, it puts the safety and transparency of the organization and the people in it first, and considers the openness of work products and data retention as secondary; sometimes (though not always) the open-source nature of the products emerges as a consequence of the nature of the organization, but the details of how that happens are community-first, code-second (and sometimes code-sort-of, code-last or code-never). “Openness” in this context is about accessibility and physical and emotional safety, about the ability to participate without fear. The checks and balances are principally about inclusivity, accessibility and community norms; codes of conduct and their enforcement.

It won’t surprise you, I suspect, to learn that environments that champion this brand of openness are much more accessible to women, minorities and otherwise marginalized members of society that make up a vanishingly small fraction of old-school open source culture. The Rust and Python communities are doing good work here, and the team at Glitch have done amazing things by putting community and collaboration ahead of everything else. But a surprising number of tool-and-platform companies, often in “pink-collar” fields, have taken the practices of open community building and turned themselves into something that, code or no, looks an awful lot like the best of what modern open source has to offer. If you can bring yourself to look past the fact that you can’t fork their code, Salesforce – Salesforce, of all the damn things – has one of the friendliest, most vibrant and supportive communities in all of software right now.

These two views aren’t going to be easy to reconcile, because the ideas of what “accountability” looks like in both contexts – and more importantly, the mechanisms of accountability built in to the systems born from both contexts – are worse than just incompatible. They’re not even addressing something the other worldview is equipped to recognize as a problem. Both are in some sense of the word open, both are to a different view effectively closed and, I think much more importantly, a lot of things that look like quotidian routine to one perspective look insanely, unacceptably dangerous to the other.

I think that’s the critical schism the dialogue, the wildly mismatched understandings of the nature of risk and freedom. Seen in that light the recent surge of attention being paid to federated systems feels like a weirdly reactionary appeal to how things were better in the old days.

I’ve mentioned before that I think it’s a mistake to think of federation as a feature of distributed systems, rather than as consequence of computational scarcity. But more importantly, I believe that federated infrastructure – that is, a focus on distributed and resilient services – is a poor substitute for an accountable infrastructure that prioritizes a distributed and healthy community. The reason Twitter is a sewer isn’t that Twitter is centralized, it’s that Jack Dorsey doesn’t give a damn about policing his platform and Twitter’s board of directors doesn’t give a damn about changing his mind. Likewise, a big reason Mastodon is popular with the worst dregs of the otaku crowd is that if they’re on the right instance they’re free to recirculate shit that’s so reprehensible even Twitter’s boneless, soporific safety team can’t bring themselves to let it slide.

That’s the other part of federated systems we don’t talk about much – how much the burden of safety shifts to the individual. The cost of evolving federated systems that require consensus to interoperate is so high that structural flaws are likely to be there for a long time, maybe forever, and the burden of working around them falls on every endpoint to manage for themselves. IRC’s (Remember IRC?) ongoing borderline-unusability is a direct product of a notion of openness that leaves admins few better tools than endless spammer whack-a-mole. Email is (sort of…) decentralized, but can you imagine using it with your junkmail filters off?

I suppose I should tip my hand at this point, and say that as much as I value the source part of open source, I also believe that people participating in open source communities deserve to be free not only to change the code and build the future, but to be free from the brand of arbitrary, mechanized harassment that thrives on unaccountable infrastructure, federated or not. We’d be deluding ourselves if we called systems that are just too dangerous for some people to participate in at all “open” just because you can clone the source and stand up your own copy. And I am absolutely certain that if this free software revolution of ours ends up in a place where asking somebody to participate in open development is indistinguishable from asking them to walk home at night alone, then we’re done. People cannot be equal participants in environments where they are subject to wildly unequal risk. People cannot be equal participants in environments where they are unequally threatened. And I’d have a hard time asking a friend to participate in an exercise that had no way to ablate or even mitigate the worst actions of the internet’s worst people, and still think of myself as a friend.

I’ve written about this before:

I’d like you to consider the possibility that that’s not enough.

What if we agreed to expand what freedom could mean, and what it could be. Not just “freedom to” but a positive defense of opportunities to; not just “freedom from”, but freedom from the possibility of.

In the long term, I see that as the future of Mozilla’s responsibility to the Web; not here merely to protect the Web, not merely to defend your freedom to participate in the Web, but to mount a positive defense of people’s opportunities to participate. And on the other side of that coin, to build accountable tools, systems and communities that promise not only freedom from arbitrary harassment, but even freedom from the possibility of that harassment.

More generally, I still believe we should work in the open as much as we can – that “default to open”, as we say, is still the right thing – but I also think we and everyone else making software need to be really, really honest with ourselves about what open means, and what we’re asking of people when we use that word. We’re probably going to find that there’s not one right answer. We’re definitely going to have to build a bunch of new tools. But we’re definitely not going to find any answers that matter to the present day, much less to the future, if the only place we’re looking is backwards.

[Feel free to email me, but I’m not doing comments anymore. Spammers, you know?]

http://exple.tive.org/blarg/2018/11/09/the-evolution-of-open/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Performance Updates and Hosting Moves: MDN Changelog for October 2018 |

|

|

Nicholas Nethercote: How to get the size of Rust types with -Zprint-type-sizes |

When optimizing Rust code it’s sometimes useful to know how big a type is, i.e. how many bytes it takes up in memory. std::mem::size_of can tell you, but often you want to know the exact layout as well. For example, an enum might be surprisingly big, in which case you probably will want to know if, for example, there is one variant that is much bigger than the others.

The -Zprint-type-sizes option does exactly this. Just pass it to a nightly version of rustc — it isn’t enabled on release versions, unfortunately — and it’ll print out details of the size, layout, and alignment of all types in use. For example, for this type:

enum E {

A,

B(i32),

C(u64, u8, u64, u8),

D(Vec),

}

it prints the following, plus info about a few built-in types:

print-type-size type: `E`: 32 bytes, alignment: 8 bytes print-type-size discriminant: 1 bytes print-type-size variant `A`: 0 bytes print-type-size variant `B`: 7 bytes print-type-size padding: 3 bytes print-type-size field `.0`: 4 bytes, alignment: 4 bytes print-type-size variant `C`: 23 bytes print-type-size field `.1`: 1 bytes print-type-size field `.3`: 1 bytes print-type-size padding: 5 bytes print-type-size field `.0`: 8 bytes, alignment: 8 bytes print-type-size field `.2`: 8 bytes print-type-size variant `D`: 31 bytes print-type-size padding: 7 bytes print-type-size field `.0`: 24 bytes, alignment: 8 bytes

It shows:

- the size and alignment of the type;

- for enums, the size of the discriminant;

- for enums, the size of each variant;

- the size, alignment, and ordering of all fields (note that the compiler has reordered variant

C‘s fields to minimize the size ofE); - the size and location of all padding.

Every detail you could possibly want is there. Brilliant!

For rustc developers, there’s an extra-special trick for getting the size of a type within rustc itself. Put code like this into a file a.rs:

#![feature(rustc_private)]

extern crate syntax;

use syntax::ast::Expr;

fn main() {

let _x = std::mem::size_of::();

}

and then compile it like this:

RUSTC_BOOTSTRAP=1 rustc -Zprint-type-sizes a.rs

I won’t pretend to understand how it works, but the use of rustc_private and RUSTC_BOOTSTRAP somehow let you see inside rustc while using it, rather than while compiling it. I have used this trick for PRs such as this one.

|

|

Nicholas Nethercote: How to get the size of Rust types with -Zprint-type-sizes |

When optimizing Rust code it’s sometimes useful to know how big a type is, i.e. how many bytes it takes up in memory. std::mem::size_of can tell you, but often you want to know the exact layout as well. For example, an enum might be surprisingly big, in which case you probably will want to know if, for example, there is one variant that is much bigger than the others.

The -Zprint-type-sizes option does exactly this. Just pass it to a nightly version of rustc — it isn’t enabled on release versions, unfortunately — and it’ll print out details of the size, layout, and alignment of all types in use. For example, for this type:

enum E {

A,

B(i32),

C(u64, u8, u64, u8),

D(Vec),

}

it prints the following, plus info about a few built-in types:

print-type-size type: `E`: 32 bytes, alignment: 8 bytes print-type-size discriminant: 1 bytes print-type-size variant `A`: 0 bytes print-type-size variant `B`: 7 bytes print-type-size padding: 3 bytes print-type-size field `.0`: 4 bytes, alignment: 4 bytes print-type-size variant `C`: 23 bytes print-type-size field `.1`: 1 bytes print-type-size field `.3`: 1 bytes print-type-size padding: 5 bytes print-type-size field `.0`: 8 bytes, alignment: 8 bytes print-type-size field `.2`: 8 bytes print-type-size variant `D`: 31 bytes print-type-size padding: 7 bytes print-type-size field `.0`: 24 bytes, alignment: 8 bytes

It shows:

- the size and alignment of the type;

- for enums, the size of the discriminant;

- for enums, the size of each variant;

- the size, alignment, and ordering of all fields (note that the compiler has reordered variant

C‘s fields to minimize the size ofE); - the size and location of all padding.

Every detail you could possibly want is there. Brilliant!

For rustc developers, there’s an extra-special trick for getting the size of a type within rustc itself. Put code like this into a file a.rs:

#![feature(rustc_private)]

extern crate syntax;

use syntax::ast::Expr;

fn main() {

let _x = std::mem::size_of::();

}

and then compile it like this:

RUSTC_BOOTSTRAP=1 rustc -Zprint-type-sizes a.rs

I won’t pretend to understand how it works, but the use of rustc_private and RUSTC_BOOTSTRAP somehow let you see inside rustc while using it, rather than while compiling it. I have used this trick for PRs such as this one.

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: Happy 8th birthday to us |

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2018/11/happy-8th-birthday-to-us.html

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: Happy 8th birthday to us |

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2018/11/happy-8th-birthday-to-us.html

|

|

David Lawrence: Happy BMO Push Day! |

https://github.com/mozilla-bteam/bmo/tree/release-20181108.1)

the following changes have been pushed to bugzilla.mozilla.org:

discuss these changes on mozilla.tools.bmo.

https://dlawrence.wordpress.com/2018/11/08/happy-bmo-push-day-49/

|

|

Firefox UX: How do people decide whether or not to get a browser extension? |

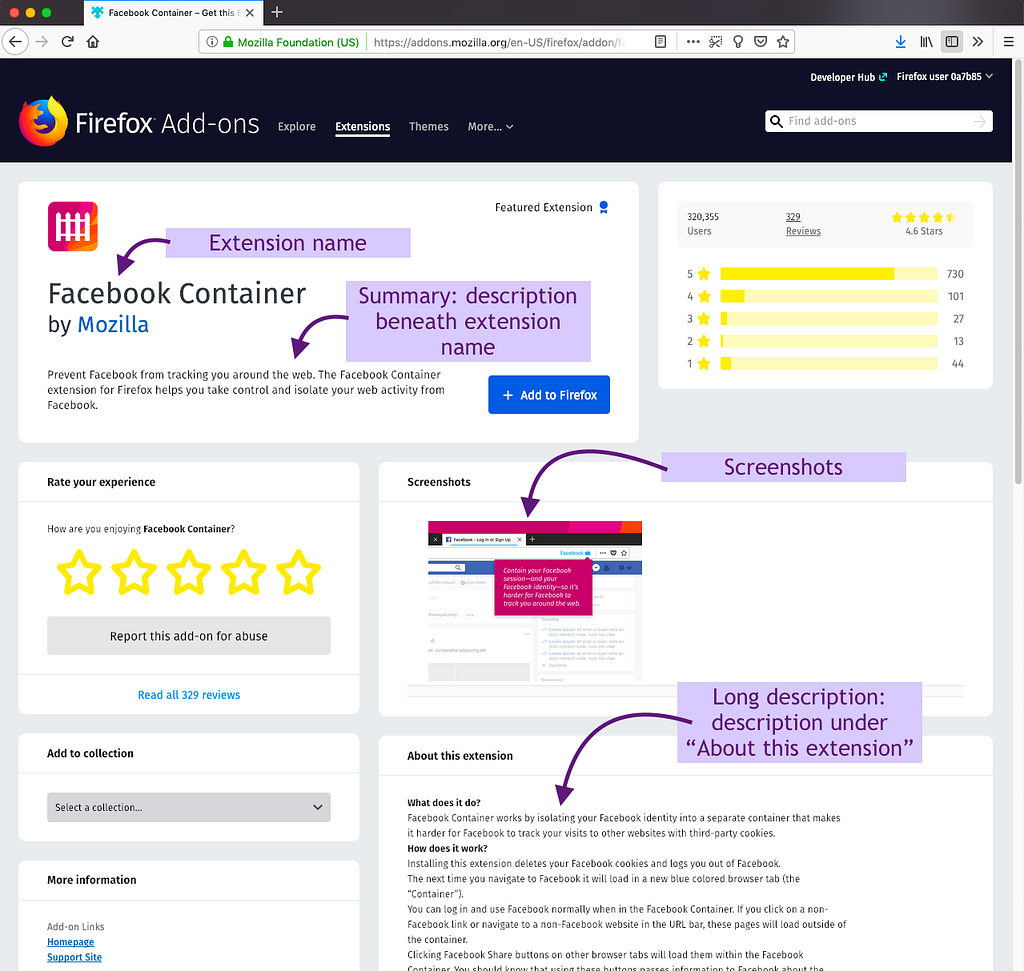

The Firefox Add-ons Team works to make sure people have all of the information they need to decide which browser extensions are right for them. Past research conducted by Bill Selman and the Add-ons Team taught us a lot about how people discover extensions, but there was more to learn. Our primary research question was: “How do people decide whether or not to get a specific browser extension?”

We recently conducted two complementary research studies to help answer that big question:

- An addons.mozilla.org (AMO) survey, with just under 7,500 respondents

- An in-person think-aloud study with nine recruited participants, conducted in Vancouver, BC

The survey ran from July 19, 2018 to July 26, 2018 on addons.mozilla.org (AMO). The survey prompt was displayed when visitors went to the site and was localized into ten languages. The survey asked questions about why people were visiting the site, if they were looking to get a specific extension (and/or theme), and if so what information they used to decide to get it.

The think-aloud study took place at our Mozilla office in Vancouver, BC from July 30, 2018 to August 1, 2018. The study consisted of 45-minute individual sessions with nine participants, in which they answered questions about the browsers they use, and completed tasks on a Windows laptop related to acquiring a theme and an extension. To get a variety of perspectives, participants included three Firefox users and six Chrome users. Five of them were extension users, and four were not.

What we learned about decision-making

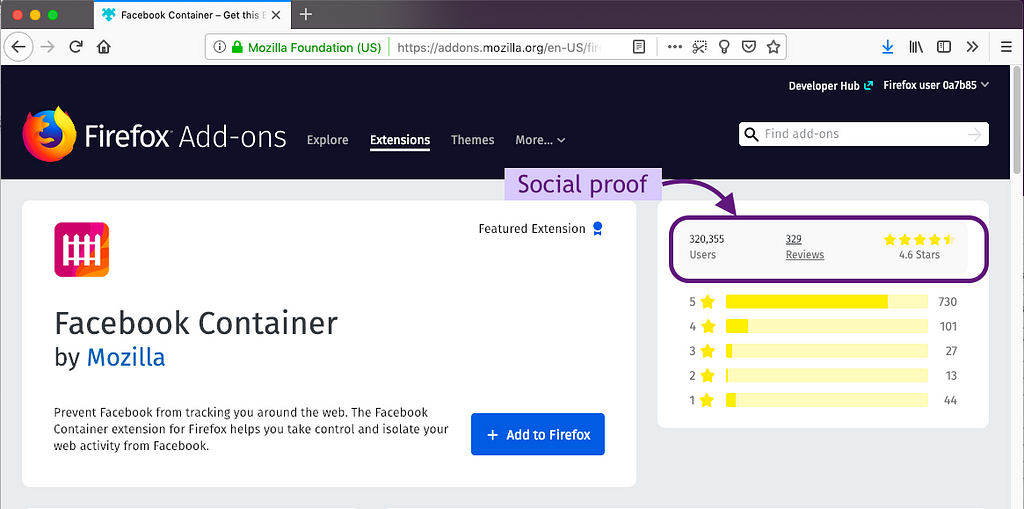

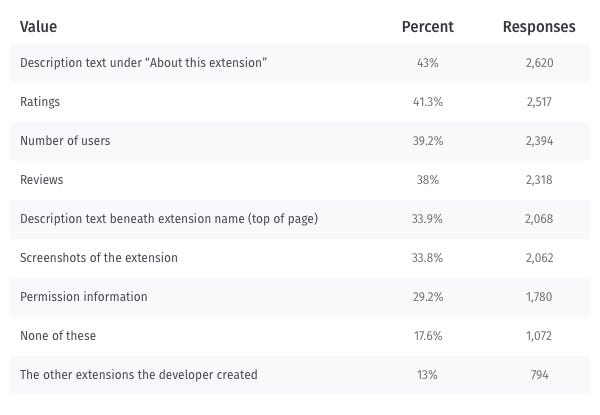

People use social proof on the extension’s product page

Ratings, reviews, and number of users proved important for making a decision to get the extension in both the survey and think-aloud study. Think-aloud participants used these metrics as a signal that an extension was good and safe. All except one think-aloud participant used this “social proof” before installing an extension. The importance of social proof was backed up by the survey responses where ratings, number of users, and reviews were among the top pieces of information used.

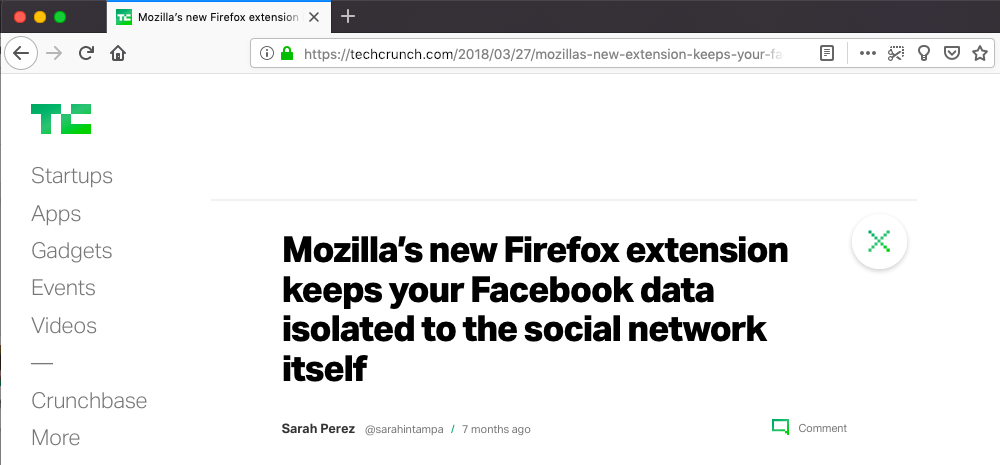

People use social proof outside of AMO

Think-aloud participants mentioned using outside sources to help them decide whether or not to get an extension. Outside sources included forums, advice from “high authority websites,” and recommendations from friends. The same result is seen among the survey respondents, where 40.6% of respondents used an article from the web and 16.2% relied on a recommendation from a friend or colleague. This is consistent with our previous user research, where participants used outside sources to build trust in an extension.

People use the description and extension name

Almost half of the survey respondents use the description to make a decision about the extension. While the description was the top piece of content used, we also see that over one-third of survey respondents evaluate the screenshots and the extension summary (the description text beneath the extension name), which shows their importance as well.

Think-aloud participants also used the extension’s description (both the summary and the longer description) to help them decide whether or not to get it.

While we did not ask about the extension name in the survey, it came up during our think-aloud studies. The name of the extension was cited as important to think-aloud participants. However, they mentioned how some names were vague and therefore didn’t assist them in their decision to get an extension.

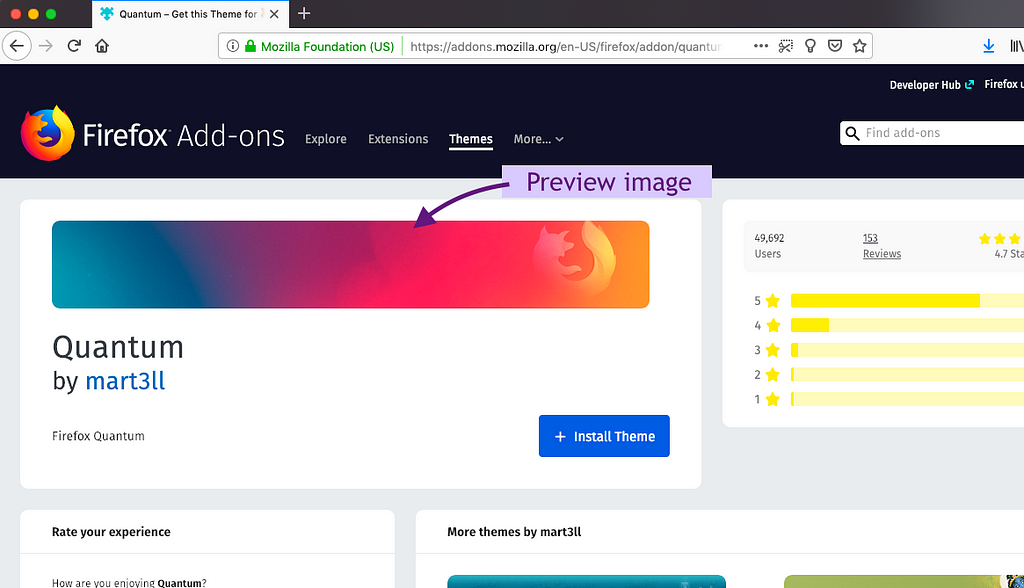

Themes are all about the picture

In addition to extensions, AMO offers themes for Firefox. From the survey responses, the most important part of a theme’s product page is the preview image. It’s clear that the imagery far surpasses any social proof or description based on this survey result.

All in all, we see that while social proof is essential, great content on the extension’s product page and in external sources (such as forums and articles) are also key to people’s decisions about whether or not to get an extension. When we’re designing anything that requires people to make an adoption decision, we need to remember the importance of social proof and great content, within and outside of our products.

In alphabetical order by first name, thanks to Amy Tsay, Ben Miroglio, Caitlin Neiman, Chris Grebs, Emanuela Damiani, Gemma Petrie, Jorge Villalobos, Kev Needham, Kumar McMillan, Meridel Walkington, Mike Conca, Peiying Mo, Philip Walmsley, Raphael Raue, Richard Bloor, Rob Rayborn, Sharon Bautista, Stuart Colville, and Tyler Downer, for their help with the user research studies and/or reviewing this blog post.

How do people decide whether or not to get a browser extension? was originally published in Firefox User Experience on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

Mozilla Addons Blog: Extensions in Firefox 64 |

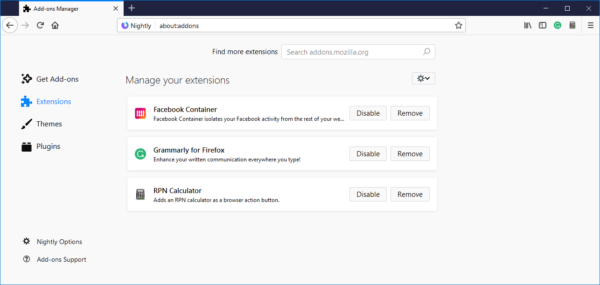

Following the explosion of extension features in Firefox 63, Firefox 64 moved into Beta with a quieter set of capabilities spread across many different areas.

Extension Management

The most visible change to extensions comes on the user-facing side of Firefox where the add-ons management page (about:addons) received an upgrade.

Changes on this page include:

Changes on this page include:

- Each extension is shown as a card that can be clicked.

- Each card shows the description for the extension along with buttons for Options, Disable and Remove.

- The search area at the top is cleaned up.

- The page links to the Firefox Preferences page (about:preferences) and that page links back to about:addons, making navigation between the two very easy. These links appear in the bottom left corner of each page.

These changes are part of an ongoing redesign of about:addons that will make managing extensions and themes within Firefox simpler and more intuitive. You can expect to see additional changes in 2019.

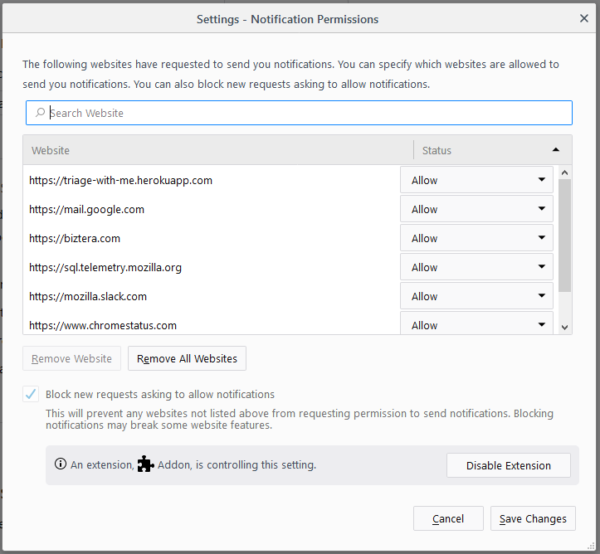

As part of our continuing effort to make sure users are aware of when an extension is controlling some aspect of Firefox, the Notification Permissions window now shows when an extension is controlling the browser’s ability to accept or reject web notification requests.

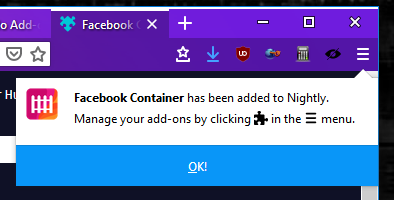

When an extension is installed, the notification popup is now persistently shown off of the main (hamburger) menu. This ensures that the notification is always acknowledged by the user and can’t be accidentally dismissed by switching tabs.

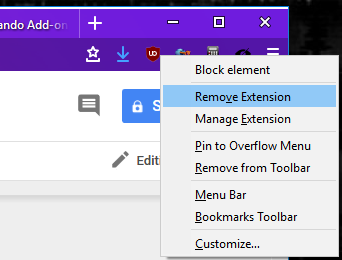

Finally, extensions can now be removed by right-clicking on an extension’s browser action icon and selecting “Remove Extension” from the resulting context menu.

Even More Context Menu Improvements

Firefox 63 saw a large number of improvements for extension context menus and, as promised, there are even more improvements in Firefox 64.

The biggest change is a new API that can be called from the contextmenu DOM event to set a custom context menu in extension pages. This API, browser.menus.overrideContext(), allows extensions to hide all default Firefox menu items in favor of providing a custom context menu UI. This context menu can consist of multiple top-level menu items from the extension, and may optionally include tab or bookmark context menu items from other extensions.

To use the new API, you must declare the menus and the brand new menus.overrideContext permission. Additionally, to include context menus from other extensions in the tab or bookmarks contexts, you must also declare the tabs or bookmarks permissions, respectively.

The API is still being documented on MDN at the time of this writing, but the API takes a contextOptions object as a parameter, which includes the following values:

showDefaults: boolean that indicates whether to include default Firefox menu items in the context menu (defaults to false)context: optional parameter that indicates theContextTypeto override to allow menu items from other extensions in this context menu. Currently, onlybookmarkandtabare supported.showDefaultscannot be used with this option.bookmarkId: required when context isbookmark. Requiresbookmarkspermission.tabId: required when context istab. Requirestabspermission.

While waiting for the MDN documentation to go live, I would highly encourage you to check out the terrific blog post by Yuki “Piro” Hiroshi that covers usage of the new API in great detail.

Other improvements to extension context menus include:

browser.menus.update()now allows extensions to update an icon without having to delete and recreate the menu item.menus.create()andmenus.update()now support a viewTypes property. This is a list of view types that specifies where the menu item will be shown and can includetab,popup(pageAction/browserAction) orsidebar. It defaults to any view, including those without a viewType.- The

menus.onShownandmenus.onClickedevents now include the viewType described above as part of their info object so extensions can determine the type of view where the menu was shown or clicked. - The

menus.onClickedevent also added a button property to indicate which mouse button initiated the click (left, middle, right).

Minor Improvements in Many Areas

In addition to the extension management in Firefox and the context menu work, many smaller improvements were made throughout the WebExtension API.

Page Actions

- A new, optional manifest property for page actions called ‘pinned’ has been added. It specifies whether or not the page action should appear in the location bar by default when the user installs the extension (default is true).

Tabs

- Extensions can now access the attention property on tabs, and can set the highlighted property from browser.tabs.update().

- An option was added to tabs.highlight() to prevent it from populating the returned window. This can have important performance benefits.

Content Scripts

- Content scripts can now read from a

Themes

- Themes can now change the sidebar border color.

Private Browsing

- On Android, fixed an issue where browser action popups opened from private browsing tabs now also open as private windows.

- Along similar lines,

tabs.create()andwindows.create()now open the about:privatebrowsing page instead of about:newtab.

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Keys on the number pad may now be used for extension keyboard shortcuts.

Dev Tools

- Extensions can now create devtools panel sidebars and use the new setPage() API to embed an extension page inside the devtools inspector sidebar.

Misc / Bug Fixes

browser.search.search()API no longer requires user input in order to be called. This makes the API much more useful, especially in asynchronous event listeners. This feature was also uplifted to Firefox 63.- Fixed the

identity.launchWebAuthFlow()API so that the redirect_uri parameter is no longer mandatory. This fixes some OAuth services that require the redirect_uri be configured on the service. - Fixed an issue so that the location bar focus is now handled properly when extensions open new tabs.

- Alarms created with a time that occurs in the past now fire immediately, instead of being ignored.

port.onMessageis now properly fired in content scripts from non-tabs locations (sidebar, extension popup views)- The filename from the download API is now properly decoded.

Thank You

A total of 73 features and improvements landed as part of Firefox 64. Volunteer contributors were a huge part of this release and a tremendous thank you goes out to our community, including: Oriol Brufau, Tomislav Jovanovic, Shivam Singhal, Tim Nguyen, Arshad Kazmi, Divyansh Sharma, Tom Schuster, Tim B, Tushar Arora, Prathiksha Guruprasad. It is the combined efforts of Mozilla and our amazing community that make Firefox a truly unique product. If you are interested in contributing to the WebExtensions ecosystem, please take a look at our wiki.

The post Extensions in Firefox 64 appeared first on Mozilla Add-ons Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/addons/2018/11/08/extensions-in-firefox-64/

|

|

Christian Legnitto: What is developer efficiency and velocity? |

As I previously mentioned I am currently in the information gathering phase for improvements to desktop Firefox developer efficiency and velocity. While many view developer efficiency and velocity as the same thing–and indeed they are often correlated–it is useful to discuss how they are different.

I like to think of developer velocity as the rate at which a unit of work is completed. Developer efficiency is the amount of effort required to complete a unit of work.

If one were to think of the total development output as revenue, improvements to velocity would improve the top-line and improvements to efficiency would improve the bottom-line.

I like to visualize the differences by imagining a lone developer with the task to write a function to compute the Fibonacci series. If one were to magically increase the developer’s typing speed, that would be an increase to their velocity. If one created a library with an existing fibonacci implementation and the developer leveraged it instead, it would be an increase to their efficiency.

The trick I am here to help Mozilla with is identifying large improvements in both Firefox developer velocity and efficiency without requiring a lot of additional resources. I am focusing on some lower-hanging fruit that the organization has missed, hasn’t deployed for everyone, or needs a trusted outsider to help push through some red tape.

https://christian.legnitto.com/blog/2018/11/08/what-is-developer-efficiency-and-velocity/

|

|

Mike Hoye: A Summer Of Code Question |

This is a lightly edited response to a question we got on IRC about how to best apply to participate in Google’s “Summer Of Code” program. this isn’t company policy, but I’ve been the one turning the crank on our GSOC application process for the last while, so maybe it counts as helpful guidance.

We’re going to apply as an organization to participate in GSOC 2019, but that process hasn’t started yet. This year it kicked off in the first week of January, and I expect about the same in 2019.

You’re welcome to apply to multiple positions, but I strongly recommend that each application be a focused effort; if you send the same generic application to all of them it’s likely they’ll all be disregarded. I recognize that this seems unfair, but we get a tidal wave of redundant applications for any position we open, so we have to filter them aggressively.

Successful GSOC applicants generally come in two varieties – people who put forward a strong application to work on projects that we’ve proposed, and people that have put together their own GSOC proposal in collaboration with one or more of our engineers.

The latter group are relatively rare, comparatively – they generally are people we’ve worked through some bugs and had some useful conversations with, who’ve done the work of identifying the “good GSOC project” bugs and worked out with the responsible engineers if they’d be open to collaboration, what a good proposal would look like, etc.

None of those bugs or conversations are guarantees of anything, perhaps obviously – some engineers just don’t have time to mentor a GSOC student, some of the things you’re interested in doing won’t make good GSOC projects, and so forth.

One of the things I hope to do this year is get better at clarifying what a good GSOC project proposal looks like, but broadly speaking they are:

- Nice-to-have features, but non-blocking and non-critical-path. A struggling GSOC student can’t put a larger project at risk.

- Few (good) or no (better) dependencies, on external factors, whether they’re code, social context or other people’s work. A good GSOC project is well-contained.

- Clearly defined yes-or-no deliverables, both overall and as milestones throughout the summer. We need GSOC participants to be able to show progress consistently.

- Finally, broad alignment with Mozilla’s mission and goals, even if it’s in a supporting role. We’d like to be able to draw a straight line between the project you’re proposing and Mozilla being incrementally more effective or more successful. It doesn’t have to move any particular needle a lot, but it has to move the needle a bit, and it has to be a needle we care about moving.

It’s likely that your initial reaction to this “that is a lot, how do I find all this out, what do I do here, what the hell”, and that’s a reasonable reaction.

The reason that this group of applicants is comparatively rare is that people who choose to go that path have mostly been hanging around the project for a bit, soaking up the culture, priorities and so on, and have figured out how to navigate from “this is my thing that I’m interested in and want to do” to “this is my explanation of how my thing fits into Mozilla, both from product engineering and an organizational mission perspective, and this is who I should be making that pitch to”.

This is not to say that it’s impossible, just that there’s no formula for it. Curiosity and patience are your most important tools, if you’d like to go down that road, but if you do we’d definitely like to hear from you. There’s no better time to get started than now.

http://exple.tive.org/blarg/2018/11/08/summer-of-code-question/

|

|

Chris H-C: Holiday Inbound: Remembrance Day 2018 |

100 years is a lot of time. It is longer than most lifetimes. It is long enough to build and erase cultures. It is long enough for the world to change.

100 years is not a lot of time. It is too short a time to forget. It isn’t long enough to understand our world. It isn’t long enough to understand each other.

This Sunday, November 11th marks the 100th anniversary of the end of hostilities of World War I. In Canada, plastic poppies have been blooming on lapels across the nation to show that we do remember the War to End All Wars. We also remember the wars that came after. And the conflicts we don’t call wars any more.

More importantly we remember those who fought them. They fought for us. They fight for us. They fight for others, too. They fight for good. We remember the fighters and their fights.

This will be the 99th Remembrance Day. This will be the 99th time we lay wreaths on cenotaphs. This will be the 99th day we add names to the list of the remembered. This will be the 99th time we mark the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month with our silence.

Silence so you can hear the rain. Silence so you can hear people nervously scuffing their feet. Silence so that even children know something is happening. Silence so loud you can’t hear a thing.

In Canada we will mark the occasion on Sunday. We will have Monday off. We will return on Tuesday.

It’ll only be a short while. We’ll be back before long.

:chutten

https://chuttenblog.wordpress.com/2018/11/08/holiday-inbound-remembrance-day-2018/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Into the Depths: The Technical Details Behind AV1 |

AV1, the next generation royalty-free video codec from the Alliance for Open Media, is making waves in the broadcasting industry.

Since AOMedia officially cemented the AV1 v1.0.0 specification earlier this year, we’ve seen increasing interest from the broadcasting industry. Starting with the NAB Show (National Association of Broadcasters) in Las Vegas earlier this year, and gaining momentum through IBC (International Broadcasting Convention) in Amsterdam, and more recently the NAB East Show in New York, AV1 keeps picking up steam. Each of these industry events attract over 100,000 media professionals. Mozilla attended these shows to demonstrate AV1 playback in Firefox, and showed that AV1 is well on its way to being broadly adopted in web browsers.

Continuing to advocate for AV1 in the broadcast space, Nathan Egge from Mozilla dives into the depths of AV1 at the Mile High Video Workshop in Denver, sponsored by Comcast.

AV1 leapfrogs the performance of VP9 and HEVC, making it a next-generation codec. The AV1 format is and will always be royalty-free with a permissive FOSS license.

The post Into the Depths: The Technical Details Behind AV1 appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2018/11/into-the-depths-the-technical-details-behind-av1/

|

|

Mozilla GFX: WebRender newsletter #29 |

To introduce this week’s newsletter I’ll write about culling. Culling refers to discarding invisible content and is performed at several stages of the rendering pipeline. During frame building on the CPU we go through all primitives and discard the ones that are off-screen by computing simple rectangle intersections. As a result we avoid transferring a lot of data to the GPU and we can skip processing them as well.

Unfortunately this isn’t enough. Web page are typically built upon layers and layers of elements stacked on top of one another. The traditional way to render web pages is to draw each element in back-to-front order, which means that for a given pixel on the screen we may have rendered many primitives. This is frustrating because there are a lot of opaque primitives that completely cover the work we did on that pixel for element beneath it, so there is a lot of shading work and memory bandwidth that goes to waste, and memory bandwidth is a very common bottleneck, even on high end hardware.

Drawing on the same pixels multiple times is called overdraw, and overdraw is not our friend, so a lot effort goes into reducing it.

In its early days, to mitigate overdraw WebRender divided the screen in tiles and all primitives were assigned to the tiles they covered (primitives that overlap several tiles would be split into a primitive for each tile), and when an opaque primitive covered an entire tile we could simply discard everything that was below it. This tiling approach was good at reducing overdraw with large occluders and also made the batching blended primitives easier (I’ll talk about batching in another episode). It worked quite well for axis-aligned rectangles which is the vast majority of what web pages are made of, but it was hard to split transformed primitives.

Eventually we decided to try a different approach inspired by how video games tackle the same problem. GPUs have a special feature called the z-buffer (or depth-buffer) into which are stored the depth of each pixel during rendering. This allows rendering opaque objects in any order and still correctly have the ones closest to the camera visible.

A common way to render 3d games is to sort objects front-to-back to maximize the chance that front-most pixels are written first and maximize the amount of shading and memory writes that are discarded by the depth test. Transparent objects are then rendered back-to-front in a second pass since they can’t count as occluders.

This is exactly what WebRender does now, and moving from the tiling scheme to using the depth buffer to reduce overdraw brought great performance improvements (certainly more than I expected), and also made a number of other things simpler (I’ll come back to these another day).

This concludes today’s little piece of WebRender history. It is very unusual for 2D rendering engines to use the z-buffer this way so I think this implementation detail is worth the highlight.

Notable WebRender and Gecko changes

- Bobby implemented dynamically growing the shared texture cache, cutting by half the remaining regression compared to Firefox without WebRender on the AWSY test.

- Dan did some profiling of the talos test, and identified large data structures being copied a lot on the stack, which led to some of Glenn’s optimizations for this week.

- Dan fixed a crash with huge box shadows.

- Kats fixed an issue with scrollbar dragging on some sites.

- Matt landed his tiled blob image work yielding nice performance improvements on some of the talos tests (45% on tsvg_static and 31% on tsvgr_opacity).

- Matt investigated the telemetry results.

- Andrew fixed a crash.

- Andrew improved animated image frame recycling (will land soon, improves performance).

- Lee fixed related to missing font descriptors.

- Glenn optimized out segment builder no-ops.

- Glenn stored text run outside primitive instances to work around a recent performance regression.

- Glenn moved opacity from per primitive instance to a per template to reduce the size of primitive instances.

- Glenn moved the resolution of opacity bindings to the shaders in order to simplify primitive interning.

- Glenn used primitive interning for text runs.

- Glenn used primitive interning for clears.

- Glenn refactored render task chaining.

- Nical made opacity, gaussian blur, and drop shadow SVG filters use WebRender’s filter infrastructure under some conditions (instead of running on the CPU fall back).

- Nical followed up with making a subset of SVG color matrix filters (the one that aren’t affected by opacity) use WebRender as well.

- Nical investigated a color conversion issue when WebRender is embedded in an application that uses OpenGL in certain ways.

- Sotaro switched presentation to triple buffering

Ongoing work

- Bobby is further improving memory usage by tweaking cache growth and eviction heuristics.

- Kats continues working on asynchronous zoom for android and on evaluating the remaining work before WebRender can be used on android.

- Kvark is making progress on simplifying the clipping and scrolling APIs.

- Matt keeps investigating performance in general.

- Glenn continues incrementally landing patches towards picture caching.

- Nical is working on blob recoordination.

- Doug is making progress on document splitting.

Enabling WebRender in Firefox Nightly

In about:

- config set “gfx.webrender.all” to true,

- restart Firefox.

https://mozillagfx.wordpress.com/2018/11/08/webrender-newsletter-29/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Mozilla Reaffirms Commitment to Transgender Equality |

As an employer, Mozilla has a long-standing commitment to diversity, inclusion and fostering a supportive work environment. In keeping with that commitment, today we join the growing list of companies publicly opposed to efforts to erase transgender protections through reinterpretation of existing laws and regulations, as well as any policy or regulation that violates the privacy rights of those who identify as transgender, gender non-binary, or intersex.

The rights, identities and humanity of transgender, gender non-binary and intersex people deserve affirmation.

A workplace that is inclusive of a diversity of backgrounds and experiences is also good for business. We’re glad to see companies across the industry joining the Human Rights Campaign’s statement and sharing this perspective.

At Mozilla, we have clear community guidelines dictating our expectations of employees and volunteers and recently rolled out workplace guidelines for transitioning individuals and their managers. These actions are a part of our commitment to ensuring a welcoming, respectful and inclusive culture.

We urge the federal government to end its exploration of policies that would erase transgender protections and erode decades of hard work to create parity, respect, opportunity and understanding for transgender professionals.

The post Mozilla Reaffirms Commitment to Transgender Equality appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2018/11/07/mozilla-reaffirms-commitment-to-transgender-equality/

|

|