Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Nick Desaulniers: Speeding up Linux kernel builds with ccache |

ccache, the compiler cache, is a fantastic way to speed up build times for C and C++ code that I previously recommended. Recently, I was playing around with trying to get it to speed up my Linux kernel builds, but wasn’t seeing any benefit. Usually when this happens with ccache, there’s something non-deterministic about the builds that prevents cache hits.

Turns out someone asked this exact question on the ccache mailing list back in 2014, and a teammate from my Android days supposed a timestamp was the culprit. That, and this LKML post from the KBUILD maintainer in 2011 about determinism helped me find commit 87c94bfb8ad35 (“kbuild: override build timestamp & version”) that introduced manually overriding part of the version string that contains the build timestamp that can be seen from:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

With ccache, we can check the cache hit/miss stats with -s, clear the cache

with -C, and clear the stats with -z. We can tell ccache explicitly which

compiler to fall back to as its first argument (not strictly necessary). For

KBUILD, we can swap our compiler by using CC= arg.

Let’s see what happens to our build time for subsequent builds with a hot cache:

No Cache

1 2 3 4 | |

Cold Cache

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 | |

Hot Cache

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | |

The initial cold cache build will be slower than not using ccache at all, but it’s a one time cost that’s not significant relative to the savings. No caching took 647.07s, initial cold cache build took 735.22s (13.62% slower), and subsequent hot cache builds took 98.9s (6.54x faster). YMMV based on CPU and disk performance. Also, it’s not the most common workflow to do clean builds, but we do this for Linux kernel builds for Android/Pixel at work, and this helps me significantly for local development.

Now, if you really need that date string in there, you theoretically could put some garbage value in there (for the cache) long enough to save enough space for a date string, then patch your vmlinux binary after the fact. I don’t recommend that, but I would imagine that might look something like:

1 2 3 | |

Deterministic builds make build caching easier, but I’m not sure that build timestamp strings and build determinism are reconcileable.

http://nickdesaulniers.github.io/blog/2018/06/02/speeding-up-linux-kernel-builds-with-ccache/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Baby’s First Rust+WebAssembly module: Say hi to JSConf EU! |

A secret project has been brewing for JSConf EU, and this weekend is the big reveal…

The Arch is a larger-than-life experience that uses 30,000 colored LEDs to create a canvas for light animations.

And you can take charge of this space. Using modules, you can create a light animation.

But even though this is JSConf, these animations aren’t just powered by JavaScript modules. In fact, we hope you will try something new… Rust + WebAssembly.

Why this project?

One of the hardest problems when you’re learning a new programming language is finding a project that can teach you the basics, but that’s still fun enough to keep you learning more. And “Hello World” is only fun your first few times… it has no real world impact.

But what if your Hello World could have an impact on the real world? What if it could control a structure like this one?

So let’s get started on baby’s first Rust to WebAssembly module.

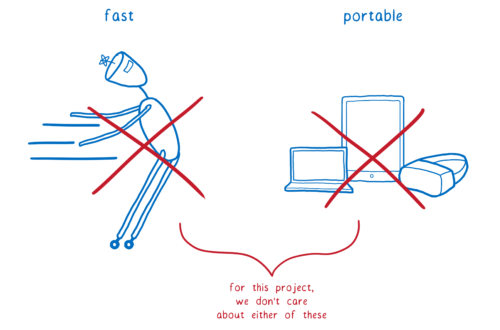

And in a way, this the perfect project for your first WebAssembly project… but not because this is the kind of project that you’d use WebAssembly for.

People usually use WebAssembly because they want to supercharge their application and make it run faster. Or because they want to use the same code across both the web and different devices, with their different operating systems.

This project doesn’t do either of those.

The reason this is a good project for getting started with WebAssembly is not because this is what you would use WebAssembly for.

Instead, it’s useful because it gives you a mental model of how JavaScript and WebAssembly work together. So let’s look at what we need to do to take control of this space with WebAssembly. And then I’ll explain why this makes it a good mental model for how WebAssembly and JavaScript work together.

The space/time continuum as bytes

What we have here is a 3D space. Or really, if you think about it, it’s more like a four dimensional space, because we’re going through time as well.

The computer can’t think in these four dimensions, though. So how do we make these four dimensions make sense to the computer? Let’s start with the fourth dimension and collapse down from there.

You’re probably familiar with the way that we make time the fourth dimension make sense to computers. That’s by using these things called frames.

The screen is kind of like a flipbook. And each frame is like a page in that flip book.

On the web, we talk about having 60 frames per second. That’s what you need to have smooth animations across the screen. What that really means is that you have 60 different snapshots of the screen… of what the animation should look like at each of those 60 points during the second.

In our case, the snapshot is a snapshot of what the lights on the space should look like.

So that brings us down to a sequence of snapshots of the space. A sequence of 3D representations of the space.

Now we want to go from 3D to 2D. And in this case, it is pretty easy. All we need to do is take the space and flatten it out into basically a big sheet of graph paper.

So now we’re down to 2D. We just need to collapse this one more time.

We can do that by taking all the rows and putting them next to each other.

Now we’re down to this line of pixels. And this we can put in memory. Because memory is basically just a line of boxes.

This means we’ve gotten it down to a one-dimensional structure. We still have all of the data that we had in a two-, three- or four-dimensional representation. It’s just being represented in a different way. It’s being represented as a line.

Why is this a good model for learning WebAssembly? Linear memory.

The reason that this is a good mental model for how WebAssembly and JavaScript work together is because one of the main ways to communicate between WebAssembly and JavaScript is through something called linear memory. It’s basically a line of memory that you use to represent things.

The WebAssembly module and the JavaScript that’s running it both have access to this object.

It’s a JavaScript object called an ArrayBuffer. An array buffer is just an array of bytes, and bytes are just numbers. So to make this animation happen, JavaScript tells the WebAssembly module, “Okay, fill in the animation now.”

It will do this by calling a method on the WebAssembly module.

WebAssembly will go and fill in all of the colors for each pixel in the linear memory.

Then the JavaScript code can pull those colors out and turn them into a JSON array that will get sent to the space.

Let’s look at how you use this data from JS.

Linear memory, the hard way

If you’re doing everything yourself and not using any libraries, then you’ll be working directly with the linear memory.

This linear memory is just one big line of 1s and 0s. When you want to create meaning from these 1s and 0s, you have to figure out how to split them up. What you do is create a typed array view on the ArrayBuffer.

Basically this just tells JavaScript how to break up the the bits in this ArrayBuffer. It’s basically like drawing boxes around the bits to say which bits belong to which number.

For example, if you were using hexadecimal values, then your numbers would be 24 bits wide. So you’d need a box that can fit 24 bits. And each box would contain a pixel.

The smallest box that would fit is 32 bits. So we would create an Int32 view on the buffer. And that would wrap the bits up into boxes. In this case we’d have to add a little padding to fill it out (I’m not showing that, but there would be extra zeros).

In contrast, if we used RGB values, the boxes would only be 8 bits wide. To get one RGB value, you would take every three boxes and use those as your R — G — and B values. This means you would iterate over the boxes and pull out the numbers.

Since we’re doing things the hard way here, you need to write the code to do this. The code will iterate over the linear memory and move the data around into more sensible data structures.

For a project like this, that’s not too bad. Colors map well to numbers, so they are easy to represent in linear memory. And the data structures we’re using (RGB values) aren’t too complex. But when you start getting more complex data structures, having to deal directly with memory can be a big pain.

It would be a lot easier if you could pass a JS object into WebAssembly and just have the WebAssembly manipulate that. And this will be possible in the future with specification work currently happening in the WebAssembly community group.

But that doesn’t mean that you have to wait until it’s in the spec before you can start working with objects. You can pass objects into your WebAssembly and return them to JS today. All you need to do is add one tiny library.

Linear memory, the easy way

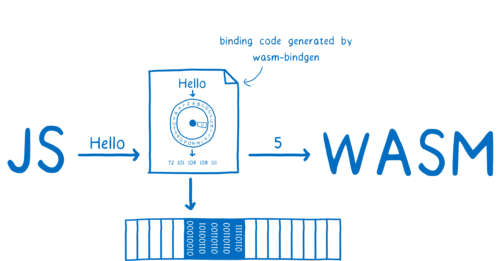

This library is called wasm-bindgen. It wraps the WebAssembly module in a JavaScript wrapper.

This wrapper knows how to take complex JavaScript objects and write them into linear memory. Then, when the WebAssembly function returns a value, the JS wrapper will take the data from linear memory and turn it back into a JS object.

To do this, it looks at the function signatures in your Rust code and figures out exactly what JavaScript is needed. This works for built-in types like strings. It also works for types that you define in your code. wasm-bidgen will take those Rust structs and turn them into JavaScript classes.

Right now, this tool is specific to Rust. But with the way that it’s architected, we can add support for this kind of higher level interaction for other languages — languages like C/C++.

In conclusion…

Hopefully you now see how to take control of this space… How you can say Hello World, and hello to the world of WebAssembly.

Before I wrap this up, I do want to give credit to the people that made this project possible.

The seeds of the idea for this project came from a dance party in a space like this I attended in Pittsburgh. But this project was only possible because of the amazing group of people that gathered to make it a reality.

- Sandra Persing — I came to her with a vision and she made that vision real

- Dan Brown and Maciej Pluta, who took that vision and turned it into something even more exciting and engaging than I had imagined

- Till Schneidereit, who helped me figure out how all the pieces fit together

- Josh Marinacci, who created the site and made taking control of the space possible

- Dan Callahan, who jumped in with his development and debugging wizardry to ensure all of the pieces worked together

- Trevor F Smith, who created the virtual space so that everyone can experience the Arch, even if they aren’t at the event

- Michael Bebenita and Yury Delendik, whose work on WebAssembly Studio makes it possible to share WebAssembly with a whole new audience

- Rustaceans: Alex Crichton, Ashley Williams, Sarah Meyers, Jan-Erik Rediger, Florian Gilcher, Steve Klabnik, Fabian, Istvan ‘Flaki’ Szmozsanszky, who worked on WebAssembly Studio’s Rust integration and helped new, aspiring Rust developers level up their skills

- The JSConf EU team for all of their hard work making sure that we could get the project off the ground

- Ian Brill, the artist who’s work inspired this project and who’s hard work ensured we could share it with you

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2018/06/babys-first-rustwebassembly-module-say-hi-to-jsconf-eu/

|

|

Mozilla Addons Blog: June’s Featured Extensions |

Pick of the Month: Tabliss

by tabliss.io

Enjoy a gorgeous new tab page with customizable background images and many informational widgets to choose from, like local weather, date/time, bookmarks, and more.

“Wow. Absolutely stunning without the need for advanced user input to make it stunning.”

Featured: View Page Archive & Cache

by Armin Sebastian

Find archived and cached versions of older web pages with the help of multiple search engines, like Wayback Machine, Google Cache, Bing Cache, and others.

“Outstanding! Often have to search multiple sites for cached pages. Very useful time-saver for me. Thank you!”

Featured: Share Backported

by Daniele Mte90 Scasciafratte

Older versions of Firefox included a social media ‘share’ button in the Toolbar. This extension brings it back to its original glory.

“Beautifully implemented!”

If you’d like to nominate an extension for featuring, please send it to amo-featured [at] mozilla [dot] org for the board’s consideration. We welcome you to submit your own add-on!

The post June’s Featured Extensions appeared first on Mozilla Add-ons Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/addons/2018/06/01/junes-featured-extensions/

|

|

Air Mozilla: SUMO Firefox 60 Post Mortem and Social Support |

This is the SUMO weekly call

This is the SUMO weekly call

https://air.mozilla.org/sumo-firefox-60-post-mortem-and-social-support/

|

|

Mozilla VR Blog: This week in Mixed Reality: Issue 8 |

Now that we are back from our Chicago work week, we are heads down adding new features, making improvements and fixing bugs.

Browsers

We are focusing on making general improvements and on the Widgets API across the Android platforms:

-

Improved the widgets API to create all the windows, widgets and placements from Java:

- Create & place all widgets from Java

- Generate ids from Java in order to avoid having to wait the callback with the C++ handler

- Remove the widget creation enumerations

- Consider moving visibility to WidgetPlacement class

- Adapt all widget children to the new API

-

Resolved startup issues in GeckoView fixing, the initial home page experience

Social

This week we spent time prioritizing features and planning for the rest of the year for the Hubs by Mozilla product:

- Added documentation of Hubs A-Frame components in the code and here

- Proof of concept of scrollable list view with react-surface, which will allow full flexbox layout + react enabled UI drawn to webgl canvas in VR

- Concluded planning and requirements doc for environment building kit, editor work kicked off this week

Join our public WebVR Slack #social channel to participate in on the discussion!

Content ecosystem

We are continuing to fix bugs found on the Unity WebVR exporter tool.

Found a critical bug? File it in our public GitHub repo or let us know on the public WebVR Slack #unity channel and as always, join us in our discussion!

Stand by for new features and improvements across our three areas next week!

|

|

Mozilla Open Innovation Team: Applying Open Practices — Sage Bionetworks |

In our series about organisations which are ‘Open by Design,’ this time we explore how Sage Bionetworks is working to enable and speed up breakthroughs in biomedical research by redefining how complex biological data is gathered, shared and used. This means challenging the traditional relationships between academic researchers, biomedical firms and ‘subjects’ to foster an ethos of data sharing. With a business model that’s dependent on shared resources and collaborative innovation, Sage Bionetworks is fundamentally ‘Open by Design.’

Alex Klepel & Gitte Jonsdatter (CIID)

Founded as a spin-out from Merck in 2009, Sage Bionetworks is a non-profit research organization that seeks to develop predictors of disease and accelerate health research by applying a large and impactful set of open practises. These allow for a global research community to share knowledge, interpret large-scale data, crowdsource hypothesis-tests and foster innovation through community challenges.

Sage relies on cloud technology, web services and consulting services to encourage and facilitate data sharing between biotech companies, researchers and research subjects. The organisation has developed three tools to support their work: Synapse, a cloud solution for sharing research data between organisations and researchers; DREAM Challenges, a crowdsourcing platform where partners can post and answer questions in biology and medicine; and Bridge, a set of web services designed to support research studies conducted via smartphone. Bridge is the engine behind Apple’s Research Kit, which made tech headlines in 2015 with the successful initial results of Sage Bionetworks’ MPower — a project to diagnose and treat Parkinson’s disease using a rich dataset gathered from thousands of iOS users.

Biomedical research is a field with a history of high investment in data-gathering studies, and a reluctance to share. In a field where being first with analysis results means everything, access to datasets is seen as a competitive advantage: products that launch before those of competitors enjoy first-mover market advantages, and for individual researchers, having study results published first improves the chances for receiving tenure and grants. This combination of business and personal career incentives has created a guarded and apprehensive culture around data that recognises only risks tied to sharing, and not the potential rewards in innovation.

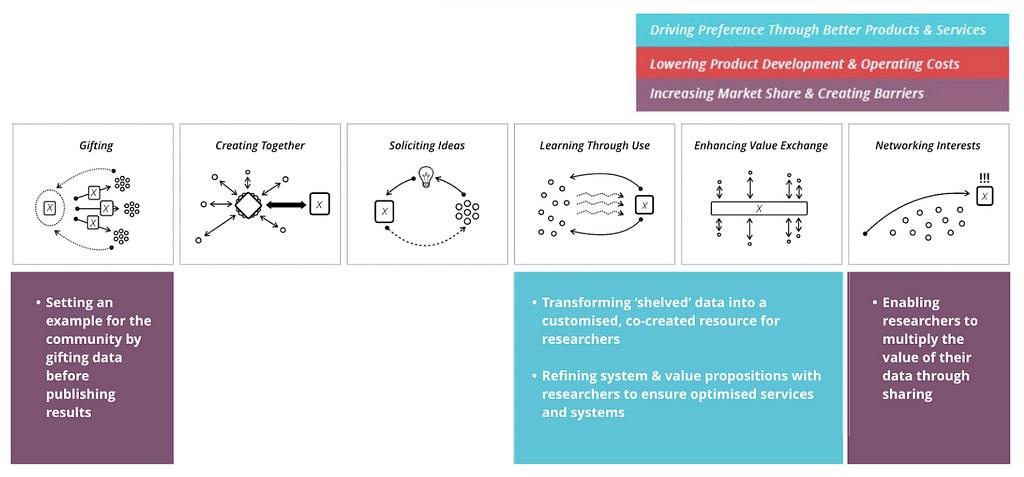

Sage Bionetworks is breaking through these systemic disincentives by identifying and communicating multi-sided opportunities, co-evolving collaboration structures that demonstrate value, and tailoring services that reward commitment to working in ways that are open.

There are several layers to this strategy:

Nudging with Tiered Pricing Models: Sage Bionetworks offers platforms to clients to conduct closed or open data projects, but data sharing has associated financial rewards. Consulting services also have varied pricing levels to encourage partners to share datasets.

Setting an Example: With the DREAM Challenges on Synapse they provide a good example and begin to shift traditional mindsets in research by gifting data to the community. The platform also provides an opportunity to reach new researchers by offering a potential reward.

Building Community in Phases: The business development team has been strategic in approaching the community in stages, starting with a few leading thinkers who share the philosophy of the value in open data. At the same time Sage is working at the structural level with the organisations that determine incentives for individual researchers.

These open networks appear to form in waves. First are the people who believe in open, then the scientists and labs that are required to participate by their funders, and then you get the most powerful incentive — fear of missing out.

John Wilbanks, Chief Commons Officer — Sage Bionetworks

A valuable lesson that Sage learned early on was that “open” is not the same as “useful”: for data to be shared, it needed to be made accessible and understandable. (Sage annotated and made available $150 million of Merck research as their first open data set. But over the course of seven years only 15–20 people asked for it.) Thus, supporting consulting services that align research needs with appropriate, discernable data has been essential in realizing the benefits of making the data accessible in the first place.

The Benefits of Participation and Collaboration

Applying a combination of communications technology, new software power, and services, Sage Bionetworks plays the role of a catalyst in a powerful research community, creating the conditions in which breakthrough discoveries can occur — by unlocking the power of combined data sources which can reveal new patterns. One stellar example of what can be achieved through collaboration is what Brian Bot, Principal Scientist and Community Manager at Sage Bionetworks, described in an interview as the “Colorectal Cancer Subtyping Consortium”. By bringing together competing research teams, building trust and commonly curating their respective molecular data sets, Sage Bionetworks enabled the unusual consortium to reinterpret contradictory research results and to see more than any each team had previously seen: a consistent signal for molecular subtypes in colorectal cancer.

We are trying to change the mental models of science. The vast majority of science is focused on the tip of iceberg — the results. But not so many people think about the mental models, values processes — and if you can combine those models and processes with the emerging technical environment, it’s possible to do science better, by doing it together, even using traditional science metrics.

John Wilbanks, Chief Commons Officer — Sage Bionetworks

Applying Open Practices — Sage Bionetworks was originally published in Mozilla Open Innovation on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

Firefox Nightly: Improving DNS Privacy in Firefox |

Domain Name Service (DNS) is one of the oldest parts of internet architecture, and remains one that has largely been untouched by efforts to make the web safer and more private. On the Firefox network and security teams, we’re working to change that by encrypting DNS queries and by testing a service that keeps DNS providers from collecting and sharing your browsing history.

For more than 30 years, DNS has served as a key mechanism for accessing sites and services on the web. Browsers (including Firefox) use DNS to access a distributed database that turns URLs into TCP/IP addressing information. Firefox cannot do much without the service. DNS hails from the days of a kinder, more gentle Internet where it was normal to make this kind of query using unencrypted protocols and send them to any nearby server who claimed to be able to answer it.

This approach is no longer a fit for the modern Internet. Because there is no encryption, other devices along the way might collect (or even block or change) this data too. DNS lookups are sent to servers that can spy on your website browsing history without either informing you or publishing a policy about what they do with that information.

While sophisticated users can turn to cloud-based “open resolvers” that offer better privacy controls than what is available by default from most internet service providers (ISPs), these resolvers rely on the same old unencrypted protocols so ISPs can often intercept data anyway.

Our first effort to upgrade the privacy of DNS is to implement the DNS over HTTPS (DoH) protocol, which encrypts DNS requests and responses. See Lin Clark’s terrific explainer about how DNS over HTTPS can really improve the state of the art.

DoH support has been added to Firefox 62 to improve the way Firefox interacts with DNS. DoH uses encrypted networking to obtain DNS information from a server that is configured within Firefox. This means that DNS requests sent to the DoH cloud server are encrypted while old style DNS requests are not protected. DoH standardization is currently a work in progress and we hope that soon many DNS servers will secure their communications with it.

Firefox does not yet use DoH by default. See the end of this post for instructions on how you can configure Nightly to use (or not use) any DoH server.

Our second effort focuses on building a default configuration for DoH servers that puts privacy first.

We are running a shield study where some Nightly users will participate in one or more experiments to help us build out a secure, cloud-based service that handles DoH requests. All Nightly users will receive an in-product notification about these studies.

Cloudflare is our partner for these experiments. When a shield study is active, Nightly Firefox will automatically use Cloudflare’s secure DNS over HTTPS service (though we aren’t using the famous 1.1.1.1 address). The first study will test whether DoH’s performance is up to the task.

We’ve chosen Cloudflare because they agreed to a very strong privacy agreement that protects your data. TCP/IP requires sharing the name of a website with a third party in order to connect, regardless of whether you’re using DoH or traditional DNS. We want to be confident your DNS operates with strong privacy preserving terms like those we have established with Cloudflare.

We believe that negotiating a privacy first operating agreement is something that Firefox can do for people that is just impractical to ask them to do for themselves. Imagine calling up your residential ISP and asking them to agree to an audit that demonstrates they do not log your IP address on their DNS server. And then repeating the process for your favorite coffee shop, library, friend’s house — anywhere you and your browser go to connect.

Firefox improves user privacy by default by finding good partners, establishing legal agreements that put privacy first, and eventually shipping a default configuration we believe is best.

Shield studies will come and go. If you would like to see what studies you are currently enrolled in simply load about:studies in the location bar. You can also opt out of studies on that page.

How-To Manually Configure DoH

Do you want to use (or not use) DoH all the time? Use the configuration editor to configure DoH if you want to test DoH outside of a shield study. DoH support works best in Firefox 62 or newer. Shield studies will not override your manual configuration.

1] Type about:config in the location bar

2] Search for network.trr (TRR stands for Trusted Recursive Resolver – it is the DoH Endpoint used by Firefox.)

3] Change network.trr.mode to 2 to enable DoH. This will try and use DoH but will fallback to insecure DNS under some circumstances like captive portals. (Use mode 5 to disable DoH under all circumstances.)

4] Set network.trr.uri to your DoH server. Cloudflare’s is https://mozilla.cloudflare-dns.com/dns-query but you can use any DoH compliant endpoint.

The DNS tab on the about:networking page indicates which names were resolved using the Trusted Recursive Resolver (TRR) via DoH.

https://blog.nightly.mozilla.org/2018/06/01/improving-dns-privacy-in-firefox/

|

|

Mozilla Localization (L10N): The importance of reviewing suggestions |

While at Mozilla we want to ensure consistent and high-quality translations, we also want to make sure that contributing is a rewarding and pleasant experience for everyone. Translating in a timely manner is important, however there are other essential things to take into consideration. For example, leaving non-urgent projects with missing strings so that new localizers can get involved is one of them. Reviewing pending suggestions regularly is another – and the main topic of this post.

In the last few months, the l10n-drivers Project Management group (Delphine, Peiying, Flod, Jeff, and Th'eo) has taken a good look at the state of pending suggestions across teams and projects in Pontoon, and has decided to take more direct action in order to ensure that localizers (newcomers and old timers alike) get timely and constructive reviews. In fact, a lack of timely replies – or worst, a total lack of replies – creates an unwelcoming environment and risks losing contributors.

We started reaching out to some teams individually – but given the amount of locales concerned, it seems a broader “call to action” at this moment is a better way to kick things out.

As a first step, we’d like communities that have more than 300 pending suggestions to go through these and take some time to bring that number down. In fact, our goal this year is not only to get a better picture of the health of the localization communities, but also to take action in order to ensure our localization communities are thriving and healthy. This is just one of many steps to get there.

The reality is that when a locale has hundreds or thousands of unreviewed suggestions, and that remain unreviewed for months, it creates an unwelcoming environment for newcomers who could have a high impact on the project with some mentorship. Seeing these high numbers will make new potential localizers think that no one is paying attention, that they will not be able to get involved effectively and that they won’t be able to make an impact. In addition to being unwelcoming, this slowly creates a closed localization community, as the lack of reviews and transparency restrict involvement to only a handful of localizers (or in some cases, one localizer alone).

In the case of teams that have thousands of unreviewed strings, one way that they can start thinking about this is if there are any projects that have become less important, that they are less passionate about, and that they do not want to work on anymore. In this case, they can simply reach out to the Project Manager in charge in order to discuss the situation. The Project Manager can also easily be found on the Pontoon UI under each project page, next to the “Contact Person” field. If still in doubt, simply reach out to the dev-l10n mailing list and we will gladly respond from there.

So, what are our next steps here? Starting in July, we will reach out to teams that still have more than 300 pending suggestions and ask that they bring that number down. In lack of response, or if no action on pending suggestions is taken, we will carefully evaluate which contributors to give more permissions to and assign translator rights to new particularly active localizers. We will also talk with them on how to coordinate the localization activity for the locale.

So this is a call to action for every locale that has pending suggestions: please help us ensure that we all have a great experience in localization at Mozilla, by not only welcoming and onboarding newcomers in your team – but also making sure everyone gets a timely review of their work.

Pontoon documentation explains what a healthy localization workflow can look like, and we invite you to take a look at it here.

https://blog.mozilla.org/l10n/2018/05/31/the-importance-of-reviewing-suggestions/

|

|

Firefox Test Pilot: Welcome Shruti to the Test Pilot team! |

A few weeks ago, Shruti Singh joined the Test Pilot team for the summer as an Outreachy intern. Read on to learn more about her and what she’ll be working on.

How would you describe your role on the Test Pilot team?

I have been selected as an Outreachy intern and would be working to “Improve sharing & contribution features on Firefox Color for Test Pilot” this summer. I started on 14th May 2018 and am very excited about the project. I will be working under the guidance of my mentor — Les Orchard.

What does a typical day at Mozilla look like for you?

It’s been a few weeks since I started working with Mozilla. A typical day at Mozilla consists of a huge amount of learning and fun. Everyone around is very helpful and friendly. I spend my time learning and implementing new things. The most interesting part is vidyo conferencing and meetings where one can meet awesome people out there and can learn/discuss technologies.

Where were you before the Test Pilot team?

I am a recent graduate student. I completed my undergraduate in computer science and engineering on 4th May 2018.

What’s coming up that you’re excited about?

Apart from doing my project, I am excited for Mozilla All-hands meeting in San Francisco, USA. The All-hands meeting is a gathering, where more than 1100 Mozilla employees and contributors of the Mozilla community come to discuss where Mozilla is heading and our future product. I can’t wait to attend the All-hands next month. :-D

Any fun side projects you’re working on (outside of work)?

During college time, I along with other friends were busy helping small kids of nearby village in learning technical subjects like maths and science. I think education and knowledge is a powerful tool to change one’s life and thought process. I am looking forward to volunteering with kids education in my city (Bangalore) too.

What is something most people at Mozilla don’t know about you?

Apart from sticking all day to my laptop, I also do sketching. It gives me a sense of peace and calm. Some of my recent sketches are:

Welcome Shruti to the Test Pilot team! was originally published in Firefox Test Pilot on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

Air Mozilla: Mozilla Science May 2018 Community Call |

Mozilla Science Lab Community Call, May We are planning a community call on May 31 at 11am PST / 2pm EST / 7pm BST /...

Mozilla Science Lab Community Call, May We are planning a community call on May 31 at 11am PST / 2pm EST / 7pm BST /...

https://air.mozilla.org/mozilla-science-lab-may-2018-bi-monthly-community-call/

|

|

Chris H-C: Distributed Teams: On the non-Universality of “Not it!” |

I’ve surprisingly not written a lot over here about working on a distributed team in a distributed organization. Mozilla is about 60% people who work in MoLos (office workers) and 40% people who don’t (remotees). My team is 50/50: I’m remote near Toronto, one works from his home in Italy, and the other two sit in the Berlin office most days.

If I expand to encompass one extra level of organization, I work with people in Toronto, San Francisco, Poland, Iowa, Illinois, more Berlin, Nova Scotia… well, you get the idea. For the past two and a half years I’ve been working with people from all over the world and I have been learning how that’s different from the rather-more-monocultural experience I had working in offices for the previous 8-10.

So today when I shouted “Not it!” into the IRC channel in response to the dawning realization that someone would have to investigate and take ownership of some test bustage, I followed it up within the minute with a cultural note:

09:35(Actually, that's a cultural thing that may need explanation. As kids, usually at summer sleep-away camp, if there is an undesirable thing that needs to be done by one person in the cabin the last person to say "Not it" is "It" and thus, has to do the undesirable thing.)

“Not it” is cultural. I think. I’ve been able to find surprisingly little about its origins in the usual places. It seems to share some heritage with the game of Tag. It seems to be an evolution of the game “Nose Goes,” but it’s hard to tell exactly where any of it started. Wikipedia can’t find an origin earlier than the 1979 Canadian film “Meatballs” where the nose game was already assumed to be a part of camp life.

Regardless of origin, I can’t assume it’s shared amongst my team. Thus my little note. Lucky for me, they seem to enjoy learning things like this. Even luckier, they enjoy sharing back. For instance, :gfritzsche once said his thumbs were pressed that we’d get something done by week’s end… what?

There were at least two things I didn’t understand about that: the first was what he meant, the second was how one pressed one’s thumbs. I mean, do you put them in your fist and squeeze, or do you press them on the outside of your fist and pretend you’re having a Thumb War (yet another cultural artefact)?

First, it means hoping for good luck. Second, it’s with thumbs inside your fist, not outside. I’m very lucky there’s a similar behaviour and expression that I’m already familiar with (“fingers crossed”). This will not always be the case, and it won’t ever be an even exchange…

All four of my team members speak the language I spoke at home while I was growing up. A lot of my culture is exported by the US via Hollywood, embedding it into the brains of the people with whom I work. I have a huge head-start on understanding and being understood, and I need to remain mindful of it.

Hopefully I’ll be able to catch some of my more egregious references before I need to explain camp songs, cringe-worthy 90s slang, or just how many hours I spent in a minivan with my siblings looking for the letter X on a license plate.

Or, then again, maybe those explanations are just part of being a distributed team?

:chutten

https://chuttenblog.wordpress.com/2018/05/31/distributed-teams-on-the-non-universality-of-not-it/

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Working for Good: Accel Lifestyle |

The web should be open to everyone, a place for unbridled innovation, education, and creative expression. That’s why Firefox fights for Net Neutrality, promotes online privacy rights, and supports open-source … Read more

The post Working for Good: Accel Lifestyle appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/working-for-good-accel-lifestyle/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: A cartoon intro to DNS over HTTPS |

Threats to users’ privacy and security are growing. At Mozilla, we closely track these threats. We believe we have a duty to do everything we can to protect Firefox users and their data.

We’re taking on the companies and organizations that want to secretly collect and sell user data. This is why we added tracking protection and created the Facebook container extension. And you’ll be seeing us do more things to protect our users over the coming months.

Two more protections we’re adding to that list are:

- DNS over HTTPS, a new IETF standards effort that we’ve championed

- Trusted Recursive Resolver, a new secure way to resolve DNS that we’ve partnered with Cloudflare to provide

With these two initiatives, we’re closing data leaks that have been part of the domain name system since it was created 35 years ago. And we’d like your help in testing them. So let’s look at how DNS over HTTPS and Trusted Recursive Resolver protect our users.

But first, let’s look at how web pages move around the Internet.

If you already know how DNS and HTTPS work, you can skip to how DNS over HTTPS helps.

A brief HTTP crash course

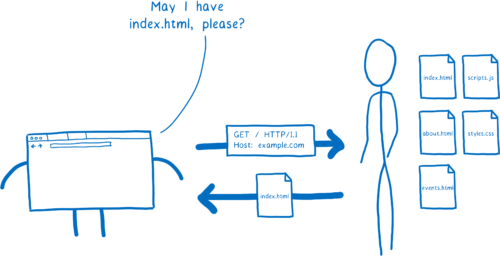

When people explain how a browser downloads a web page, they usually explain it this way:

- Your browser makes a GET request to a server.

- The server sends a response, which is a file containing HTML.

This system is called HTTP.

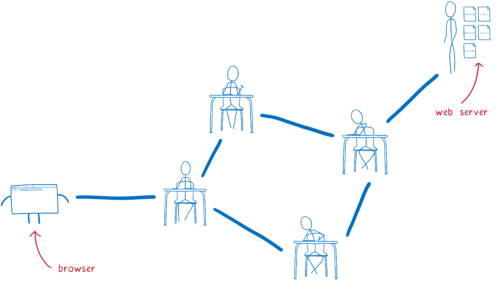

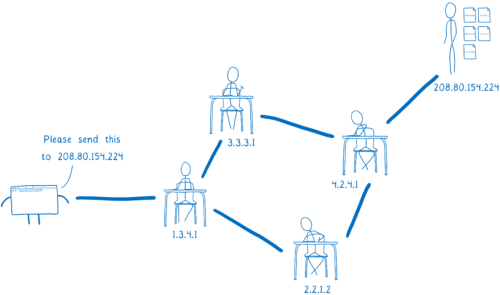

But this diagram is a little oversimplified. Your browser doesn’t talk directly to the server. That’s because they probably aren’t close to each other.

Instead, the server could be thousands of miles away. And there’s likely no direct link between your computer and the server.

So this request needs to get from the browser to that server, and it will go through multiple hands before it gets there. And the same is true for the response coming back from the server.

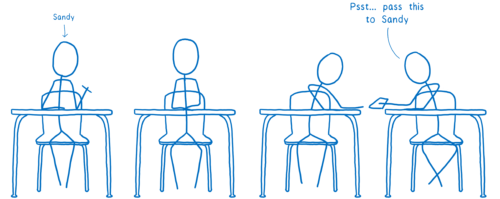

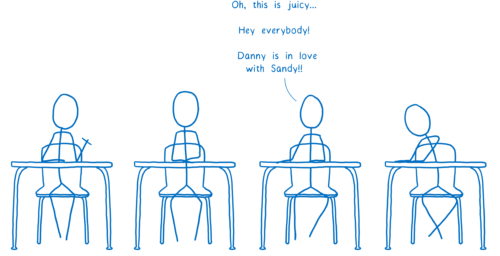

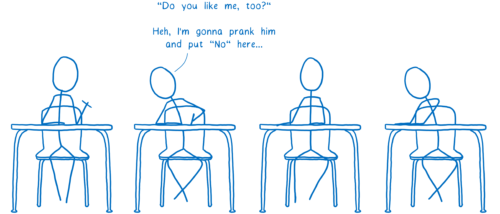

I think of this like kids passing notes to each other in class. On the outside, the note will say who it’s supposed to go to. The kid who wrote the note will pass it to their neighbor. Then that next kid passes it to one of their neighbors — probably not the eventual recipient, but someone who’s in that direction.

The problem with this is that anyone along the path can open up the note and read it. And there’s no way to know in advance which path the note is going to take, so there’s no telling what kind of people will have access to it.

It could end up in the hands of people who do harmful things…

Like sharing the contents of the note with everyone.

Or changing the response.

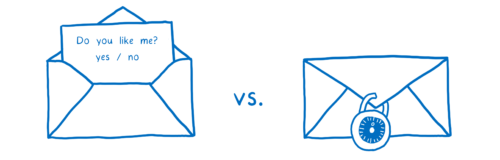

To fix these issues, a new, secure version of HTTP was created. This is called HTTPS. With HTTPS, it’s kind of like each message has a lock on it.

Both the browser and the server know the combination to that lock, but no one in between does.

With this, even if the messages go through multiple routers in between, only you and the web site will actually be able to read the contents.

This solves a lot of the security issues. But there are still some messages going between your browser and the server that aren’t encrypted. This means people along the way can still pry into what you’re doing.

One place where data is still exposed is in setting up the connection to the server. When you send your initial message to the server, you send the server name as well (in a field called “Server Name Indication”). This lets server operators run multiple sites on the same machine while still knowing who you are trying to talk to. This initial request is part of setting up encryption, but the initial request itself isn’t encrypted.

The other place where data is exposed is in DNS. But what is DNS?

DNS: the Domain Name System

In the passing notes metaphor above, I said that the name of the recipient had to be on the outside of the note. This is true for HTTP requests too… they need to say who they are going to.

But you can’t use a name for them. None of the routers would know who you were talking about. Instead, you have to use an IP address. That’s how the routers in between know which server you want to send your request to.

This causes a problem. You don’t want users to have to remember your site’s IP address. Instead, you want to be able to give your site a catchy name… something that users can remember.

This is why we have the domain name system (DNS). Your browser uses DNS to convert the site name to an IP address. This process — converting the domain name to an IP address — is called domain name resolution.

How does the browser know how to do this?

One option would be to have a big list, like a phone book in the browser. But as new web sites came online, or as sites moved to new servers, it would be hard to keep that list up-to-date.

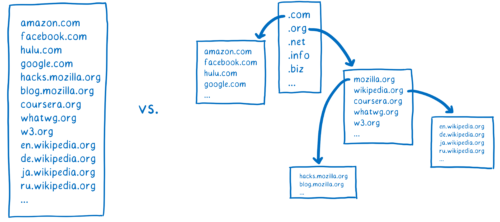

So instead of having one list which keeps track of all of the domain names, there are lots of smaller lists that are linked to each other. This allows them to be managed independently.

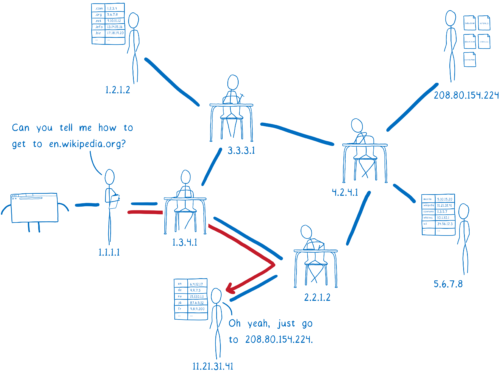

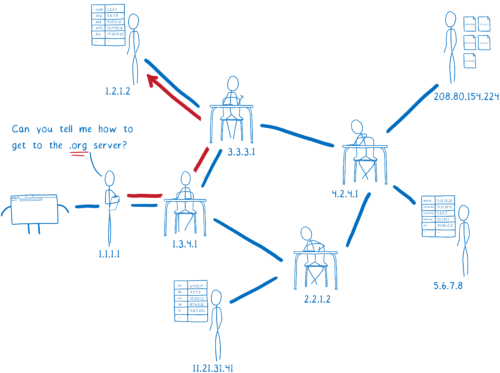

In order to get the IP address that corresponds to a domain name, you have to find the list that contains that domain name. Doing this is kind of like a treasure hunt.

What would this treasure hunt look like for a site like the English version of wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org?

We can split this domain into parts.

With these parts, we can hunt for the list that contains the IP address for the site. We need some help in our quest, though. The tool that will go on this hunt for us and find the IP address is called a resolver.

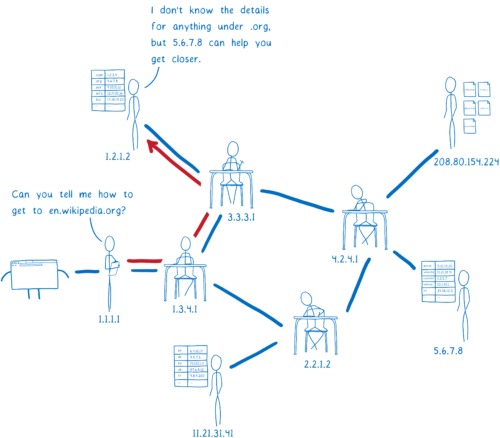

First, the resolver talks to a server called the Root DNS. It knows of a few different Root DNS servers, so it sends the request to one of them. The resolver asks the Root DNS where it can find more info about addresses in the .org top-level domain.

The Root DNS will give the resolver an address for a server that knows about .org addresses.

This next server is called a top-level domain (TLD) name server. The TLD server knows about all of the second-level domains that end with .org.

It doesn’t know anything about the subdomains under wikipedia.org, though, so it doesn’t know the IP address for en.wikipedia.org.

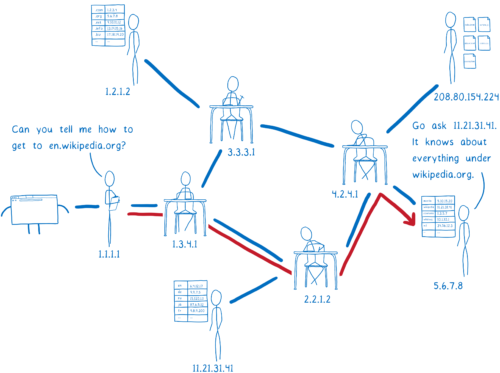

The TLD name server will tell the resolver to ask Wikipedia’s name server.

The resolver is almost done now. Wikipedia’s name server is what’s called the authoritative server. It knows about all of the domains under wikipedia.org. So this server knows about en.wikipedia.org, and other subdomains like the German version, de.wikipedia.org. The authoritative server tells the resolver which IP address has the HTML files for the site.

The resolver will return the IP address for en.wikipedia.org to the operating system.

This process is called recursive resolution, because you have to go back and forth asking different servers what’s basically the same question.

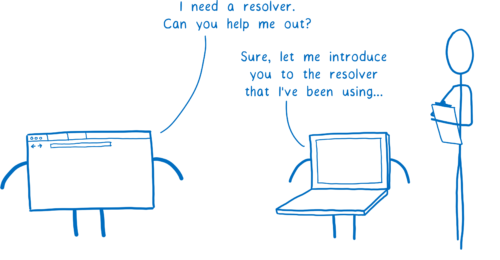

I said we need a resolver to help us in our quest. But how does the browser find this resolver? In general, it asks the computer’s operating system to set it up with a resolver that can help.

How does the operating system know which resolver to use? There are two possible ways.

You can configure your computer to use a resolver you trust. But very few people do this.

Instead, most people just use the default. And by default, the OS will just use whatever resolver the network told it to. When the computer connects to the network and gets its IP address, the network recommends a resolver to use.

This means that the resolver that you’re using can change multiple times per day. If you head to the coffee shop for an afternoon work session, you’re probably using a different resolver than you were in the morning. And this is true even if you have configured your own resolver, because there’s no security in the DNS protocol.

How can DNS be exploited?

So how can this system make users vulnerable?

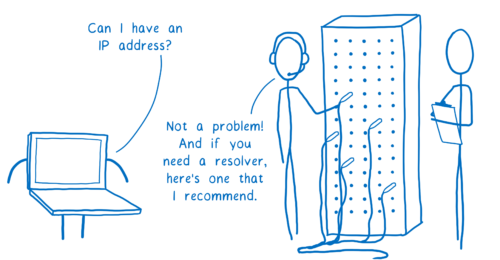

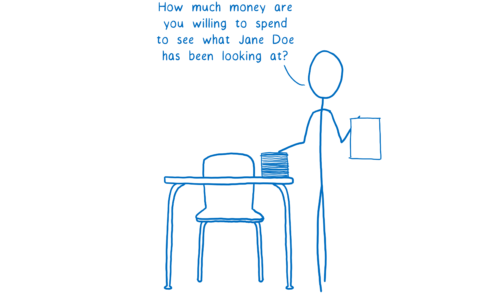

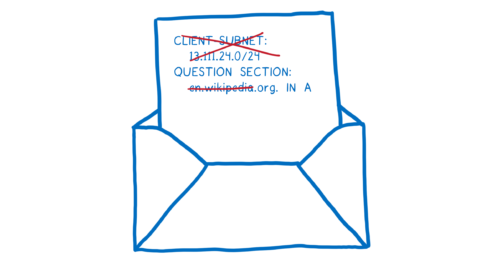

Usually a resolver will tell each DNS server what domain you are looking for. This request sometimes includes your full IP address. Or if not your full IP address, increasingly often the request includes most of your IP address, which can easily be combined with other information to figure out your identity.

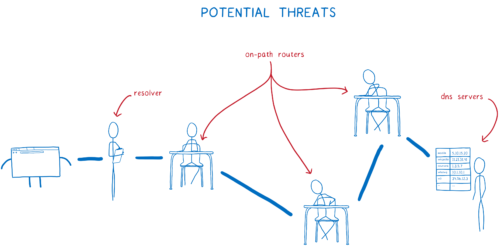

This means that every server that you ask to help with domain name resolution sees what site you’re looking for. But more than that, it also means that anyone on the path to those servers sees your requests, too.

There are a few ways that this system puts users’ data at risk. The two major risks are tracking and spoofing.

Tracking

Like I said above, it’s easy to take the full or partial IP address info and figure out who’s asking for that web site. This means that the DNS server and anyone along the path to that DNS server — called on-path routers — can create a profile of you. They can create a record of all of the web sites that they’ve seen you look up.

And that data is valuable. Many people and companies will pay lots of money to see what you are browsing for.

Even if you didn’t have to worry about the possibly nefarious DNS servers or on-path routers, you still risk having your data harvested and sold. That’s because the resolver itself — the one that the network gives to you — could be untrustworthy.

Even if you trust your network’s recommended resolver, you’re probably only using that resolver when you’re at home. Like I mentioned before, whenever you go to a coffee shop or hotel or use any other network, you’re probably using a different resolver. And who knows what its data collection policies are?

Beyond having your data collected and then sold without your knowledge or consent, there are even more dangerous ways the system can be exploited.

Spoofing

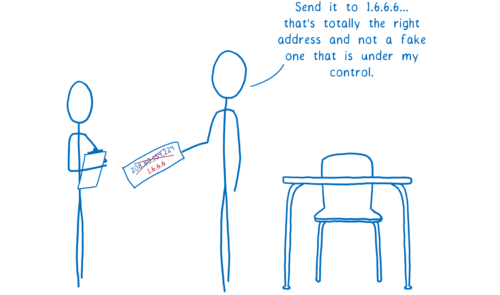

With spoofing, someone on the path between the DNS server and you changes the response. Instead of telling you the real IP address, a spoofer will give you the wrong IP address for a site. This way, they can block you from visiting the real site or send you to a scam one.

Again, this is a case where the resolver itself might act nefariously.

For example, let’s say you’re shopping for something at Megastore. You want to do a price check to see if you can get it cheaper at a competing online store, big-box.com.

But if you’re on Megastore WiFi, you’re probably using their resolver. That resolver could hijack the request to big-box.com and lie to you, saying that the site is unavailable.

How can we fix this with Trusted Recursive Resolver (TRR) and DNS over HTTPS (DoH)?

At Mozilla, we feel strongly that we have a responsibility to protect our users and their data. We’ve been working on fixing these vulnerabilities.

We are introducing two new features to fix this — Trusted Recursive Resolver (TRR) and DNS over HTTPS (DoH). Because really, there are three threats here:

- You could end up using an untrustworthy resolver that tracks your requests, or tampers with responses from DNS servers.

- On-path routers can track or tamper in the same way.

- DNS servers can track your DNS requests.

So how do we fix these?

- Avoid untrustworthy resolvers by using Trusted Recursive Resolver.

- Protect against on-path eavesdropping and tampering using DNS over HTTPS.

- Transmit as little data as possible to protect users from deanonymization.

Avoid untrustworthy resolvers by using Trusted Recursive Resolver

Networks can get away with providing untrustworthy resolvers that steal your data or spoof DNS because very few users know the risks or how to protect themselves.

Even for users who do know the risks, it’s hard for an individual user to negotiate with their ISP or other entity to ensure that their DNS data is handled responsibly.

However, we’ve spent time studying these risks… and we have negotiating power. We worked hard to find a company to work with us to protect users’ DNS data. And we found one: Cloudflare.

Cloudflare is providing a recursive resolution service with a pro-user privacy policy. They have committed to throwing away all personally identifiable data after 24 hours, and to never pass that data along to third-parties. And there will be regular audits to ensure that data is being cleared as expected.

With this, we have a resolver that we can trust to protect users’ privacy. This means Firefox can ignore the resolver that the network provides and just go straight to Cloudflare. With this trusted resolver in place, we don’t have to worry about rogue resolvers selling our users’ data or tricking our users with spoofed DNS.

Why are we picking one resolver? Cloudflare is as excited as we are about building a privacy-first DNS service. They worked with us to build a DoH resolution service that would serve our users well in a transparent way. They’ve been very open to adding user protections to the service, so we’re happy to be able to collaborate with them.

But this doesn’t mean you have to use Cloudflare. Users can configure Firefox to use whichever DoH-supporting recursive resolver they want. As more offerings crop up, we plan to make it easy to discover and switch to them.

Protect against on-path eavesdropping and tampering using DNS over HTTPS

The resolver isn’t the only threat, though. On-path routers can track and spoof DNS because they can see the contents of the DNS requests and responses. But the Internet already has technology for ensuring that on-path routers can’t eavesdrop like this. It’s the encryption that I talked about before.

By using HTTPS to exchange the DNS packets, we ensure that no one can spy on the DNS requests that our users are making.

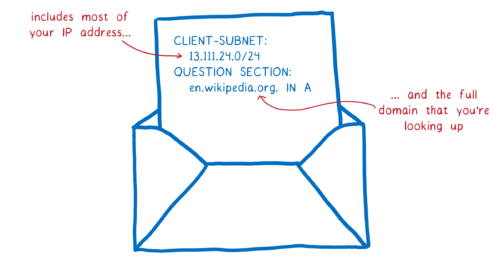

Transmit as little data as possible to protect users from deanonymization

In addition to providing a trusted resolver which communicates using the DoH protocol, Cloudflare is working with us to make this even more secure.

Normally, a resolver would send the whole domain name to each server—to the Root DNS, the TLD name server, the second-level name server, etc. But Cloudflare will be doing something different. It will only send the part that is relevant to the DNS server it’s talking to at the moment. This is called QNAME minimization.

The resolver will also often include the first 24 bits of your IP address in the request. This helps the DNS server know where you are and pick a CDN closer to you. But this information can be used by DNS servers to link different requests together.

Instead of doing this, Cloudflare will make the request from one of their own IP addresses near the user. This provides geolocation without tying it to a particular user. In addition to this, we’re looking into how we can enable even better, very fine-grained load balancing in a privacy-sensitive way.

Doing this — removing the irrelevant parts of the domain name and not including your IP address — means that DNS servers have much less data that they can collect about you.

What isn’t fixed by TRR with DoH?

With these fixes, we’ve reduced the number of people who can see what sites you’re visiting. But this doesn’t eliminate data leaks entirely.

After you do the DNS lookup to find the IP address, you still need to connect to the web server at that address. To do this, you send an initial request. This request includes a server name indication, which says which site on the server you want to connect to. And this request is unencrypted.

That means that your ISP can still figure out which sites you’re visiting, because it’s right there in the server name indication. Plus, the routers that pass that initial request from your browser to the web server can see that info too.

However, once you’ve made that connection to the web server, then everything is encrypted. And the neat thing is that this encrypted connection can be used for any site that is hosted on that server, not just the one that you initially asked for.

This is sometimes called HTTP/2 connection coalescing, or simply connection reuse. When you open a connection to a server that supports it, that server will tell you what other sites it hosts. Then you can visit those other sites using that existing encrypted connection.

Why does this help? You don’t need to start up a new connection to visit these other sites. This means you don’t need to send that unencrypted initial request with its server name indication saying which site you’re visiting. Which means you can visit any of the other sites on the same server without revealing what sites you’re looking at to your ISP and on-path routers.

With the rise of CDNs, more and more independent sites are being served by a single server. And since you can have multiple coalesced connections open, you can be connected to multiple shared servers or CDNs at once, visiting all of the sites across the different servers without leaking data. This means this will be more and more effective as a privacy shield.

What is the status?

You can enable DNS over HTTPS in Firefox today, and we encourage you to.

We’d like to turn this on as the default for all of our users. We believe that every one of our users deserves this privacy and security, no matter if they understand DNS leaks or not.

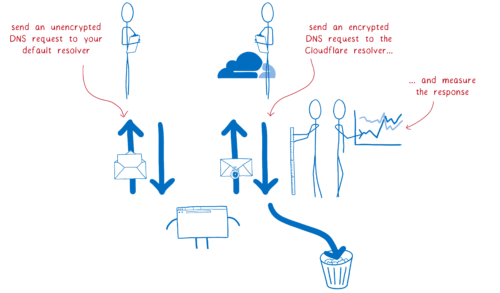

But it’s a big change and we need to test it out first. That’s why we’re conducting a study. We’re asking half of our Firefox Nightly users to help us collect data on performance.

We’ll use the default resolver, as we do now, but we’ll also send the request to Cloudflare’s DoH resolver. Then we’ll compare the two to make sure that everything is working as we expect.

For participants in the study, the Cloudflare DNS response won’t be used yet. We’re simply checking that everything works, and then throwing away the Cloudflare response.

We are thankful to have the support of our Nightly users — the people who help us test Firefox every day — and we hope that you will help us test this, too.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2018/05/a-cartoon-intro-to-dns-over-https/

|

|

Mark C^ot'e: A Vision for Engineering Workflow at Mozilla (part one) |

The OED’s second definition of “vision” is “the ability to think about or plan the future with imagination or wisdom.” Thus I felt more than a little trepidation when I was tasked with creating a vision for my team. What should this look like? How do I scope it? What should it cover? The Internet was of surprisingly little help; it seems that either no one thinks about tooling and engineering processes at this level, or (perhaps more likely) they keep it a secret when they do. The best article I found was from Microsoft Research in which they studied how tools are adopted at Microsoft, and their conclusion was essentially that they had no overarching strategy.

Around six months later, I presented a Vision for Engineering Workflow at our fortnightly managers' meeting. But first, some context: a bit about Mozilla’s Engineering Workflow team, and about the challenges we face.

Engineering Workflow

The Engineering Workflow team was created in the Great Reorg of 2017, when, amongst other large changes, its predecessor, the Automation & Tools team (aka the A-Team) was split into two, with the part focussed more on test automation joining the newly formed Product Integrity org. The other half remained in the Engineering Operations org, along with a related team, managed by coop, that worked on the build and version-control systems. In February, these two teams were consolidated into a single team, with kmoir joining the team as a new manager while coop headed off to manage the Taskcluster team.

We named this new team “Engineering Workflow” to reflect that it is focussed on the first stages of the Firefox engineering pipeline, that is, tools and processes that most developers use on a day-to-day basis. Our mission is as follows:

The engineering workflow team exists to improve the quality, clarity, and efficiency of Firefox development through the integration and development of tools and automation.

More specifically, the major pieces of the engineering pipeline that we work on are

- Tracking issues

- Reviewing code

- Landing code

- Building Firefox

Just as importantly, there are many related systems that we don’t own. These include

- Tests and test frameworks. As mentioned above, these are the responsibility of the Product Integrity org.

- Release and update infrastructure. This is the domain of release engineering and release management.

- Metrics related to product use. Although we are starting to collect our own metrics, data related to Firefox itself is collected and analyzed by the data and product teams.

- Firefox Developer Experience (aka devtools). I mention this only because they have (or at least had) a similar name. This is the team that works on the developer tools that are shipped as part of Firefox.

- Low-level tools. These tools are very product focussed, requiring intimate knowledge of the Firefox codebase and C++ development. This team is managed by Anthony Jones and is part of the Runtime Engineering group.

- Products not built from mozilla-central. To allow us to focus (I seem to really love that word), we prioritize work to help developers working within the mozilla-central codebase. Many of our tools are also used by other teams (including ourselves!) but support requests from them are considered lower priority.

Of course, we can and do work with many of these other teams on joint ventures. Over time I would like to better coordinate our respective road maps to deliver even more impact to engineering at Mozilla.

Challenges

Mozilla is a unique place. Not only are we a nonprofit that works in the open, but we develop a massive application with contributors, both paid and volunteer, located all around the world. This means we also face unique challenges when it comes to figuring out what tools and automation to integrate, build, and/or improve to maximize impact. I’ll touch on a few here.

Diverse workflows and strong preferences

Tales of “religious wars” within software develop stretch back decades, so it is no surprise that many Mozillians have strong opinions about the way they prefer to work. What is less common is that Mozilla has generally shied away from defining official (or even officially supported) tools and processes. I won’t get into the merits of this approach, but it does impact tooling teams, who have to either support multiple workflows in their tools or unilaterally decide to prioritize some over others.

A few examples:

- git versus modern hg versus mq. Not only are developers split across two VCSes, but even within Mercurial users there are differences (though thankfully mq usage seems to be much lower than a few years ago).

- microcommits and commit series. Some developers tend to create a single patch per bug. A good number create a few patches per bug, sometimes as followups but often as one chunk of work. And there are a small number who, at least at times, create long series of commits, sometimes on the order of 20 to 40. Furthermore, despite the growing popularity of the commit-series philosophy, including at Mozilla, proper support in review tools remains rare.

- importance of features in code-review and issue-tracking apps. Unsurprisingly, as developers spend much of their days working with bugs and code changes, they tend to get opinionated as to how the tools could be made better. It’s tricky to know which features to prioritize when both improving and migrating tools.

I am happy to report, however, that there is more and more support for consolidating workflows at Mozilla.

Engineering scale

Firefox is a huge application. A full Mercurial clone currently takes up 3.6 GB of disk space. Without Mercurial metadata the codebase, including build, test, and third-party libs and apps, contains over 245 000 files in more than 17 000 directories totalling almost 20 million lines of code. There aren’t too many projects the size of Firefox, open source or otherwise.

Unsurprisingly, since Firefox remains very active, there are a lot of changes going into the codebase: about 180 per day in April 2018. Contrast this with about 25-30 per day going into the Linux kernel. This also doesn’t count pushes to the try server for testing works in progress. April saw 210 compute years in our CI system.

Finally, we have complicated security requirements. Mozilla is open by design, with many tools and processes exposed to the public (and the public Internet!). Our approach to governance does not restrict positions of authority and responsibility to employees. These complexities and subleties can be seen in BMO’s permission system, which is much more fine-grained than what is built into most issue-tracking and code-review tools.

All these factors create difficult problems when integrating third-party tools into our systems. In addition, although we do this less than we used to, our scale means that there are not always existing solutions out there that meet our needs, requiring us to write custom applications that need to be highly scalable and secure.

Legacy

Related to the scale of Firefox development is its long legacy. The Mozilla Foundation is 20 years old, with the Netscape code dating back even further. Although Mozilla has grown dramatically as an entity, many workflows persist over the years, including the reviewing of patches in Bugzilla and the use of Mercurial queues. Understandably, when developers have used a certain workflow for many years, they are often skeptical of change. Yet newer contributors are more familiar with modern workflows, so modern tooling can help attract and retain both employees and volunteers, in addition to the various other advantages in terms of ergonomics, usability, and efficiency. Contending with these two perspectives can be difficult.

In addition to legacy workflows, we also have a number of legacy systems. Many of these systems continue to serve us well, and we are constantly making improvements to them. However, large-scale changes can be difficult, both because of the age of these systems and codebases, but also because over time they have been integrated with many other applications and used in ways we aren’t aware of and sometimes don’t expect. This makes planning challenging and requires a lot of communication.

Decision-making and responsibility

I’m happy to say that this set of challenges has seen the most improvement of the ones I’ve highlighted. I’ll mention them regardless as we can always be improving, and an understanding of our history helps.

Decision-making at Mozilla has been challenging for a number of reasons, mainly due to its history and rapid growth. In particular, there was a common view that we aimed for consensus on all major decisions, which, while well-intentioned, did not scale, and in fact was contradicted by both our management and module systems. This has led both to stalled decisions and sudden decisions that avoided discussions altogether. I’ve previously written about my perspectives and experiences in making decisions at Mozilla. Thankfully, as I also noted, this culture is changing, and making effective, reasoned decisions is getting easier.

Within my own team, or at least its previous incarnation as the A-Team, we experienced our own difficulties making decisions and prioritizing work. There were no clear lines of authority and responsibility when it came to tooling, which also contributed to our team becoming too service oriented. Again, this is changing for the better with existence of both Engineering Operations and Product Integrity, whose directors are peers of those of the product-focussed departments.

Thus ends my preamble on the context of developing a Vision for Engineering Workflow. In my next post, I’ll delve into the Vision itself.

https://mrcote.info/blog/2018/05/31/a-vision-for-engineering-workflow-at-mozilla-part-one/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: curl, http2 and quic on the Changelog |

Three years ago I talked on a changelog episode about curl just having turned 17 years old and what it has meant for me etc.

Fast forward three years, 146 changelog episodes later and now curl has turned 20 years and I was again invited and joined the lovely hosts of the changelog podcast, Adam and Jerod.

We talked curl of course but we also spent time talking about where HTTP/2 is and how QUIC is coming around and a little about why and how its UDP nature makes things a little different. If you're into either curl or web transport, I hope you'll find it interesting.

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2018/05/31/curl-http2-and-quic-on-the-changelog/

|

|

David Lawrence: Happy BMO Push Day! |

the following changes have been pushed to bugzilla.mozilla.org:

- [1462685] Use Phabricators Draft functionality to allow sending of initial revision email after BMO has updated the policies

- [1464226] quicksearch can’t search for “Resolution:—“

- [1464312] Write script to undo the INACTIVE changes on bugs

- [1465225] New changes for draft revisions can miss setting permissions on revisions without a bug id associated

discuss these changes on mozilla.tools.bmo.

https://dlawrence.wordpress.com/2018/05/30/happy-bmo-push-day-43/

|

|

Air Mozilla: MoFo Staff Call May 2018 |

MoFo Staff Call May 2018

MoFo Staff Call May 2018

|

|

Henrik Skupin: What to do when Firefox crashes under test automation with Selenium |

If you have the task to create automated tests for websites you will most likely make use of Selenium when it comes to testing UI interactions. To execute the tests for the various browsers out there each browser vendor offers a so called driver package which has to be used by Selenium to run each of the commands. In case of Firefox this will be geckodriver.

Within the last months we got a couple of issues reported for geckodriver that Firefox sometimes crashes while the tests are running. This feedback is great, and we always appreciate because it helps us to make Firefox more stable and secure for our users. But to actually being able to fix the crash we would need some more data, which was a bit hard to retrieve in the past.

As first step I worked on the Firefox crash reporter support for geckodriver and we got it enabled in the 0.19.0 release. While this was fine and the crash reporter created minidump files for each of the crashes in the temporarily created user profile for Firefox, this data gets also removed together with the profile once the test has been finished. So copying the data out of the profile was impossible.

As of now I haven’t had the time to improve the user experience here, but I hope to be able to do it soon. The necessary work which already got started will be covered on bug 1433495. Once the patch on that bug has been landed and a new geckodriver version released, the environment variable “MINIDUMP_SAVE_PATH” can be used to specify a target location for the minidump files. Then geckodriver will automatically copy the files to this target folder before the user profile gets removed.

But until that happened a bit of manual work is necessary. Because I had to mention those steps a couple of time and I don’t want to repeat that in the near future again and again, I decided to put up a documentation in how to analyze the crash data, and how to send the data to us. The documentation can be found at:

https://firefox-source-docs.mozilla.org/testing/geckodriver/doc/geckodriver/CrashReports.html

I hope that helps!

|

|

Armen Zambrano: Neutrino: Deploying to Netlify |

Neutrino is my preferred tool to kickstart a React app and Netlify is my preferred SPA deployment service.

Netlify makes it very easy to deploy your static sites, however, it needs some initial configuration.

You won’t find Neutrino as one of the tools listed in their docs, thus, adding some docs in here. We’ll see if my instructions are right and maybe ask them to include them in their docs.

When you create a new site you will connect your repository and you will be asked to fill in the following:

- Branch to deploy: master // Selected by default

- Build command: yarn build

- Publish directory: build // Neutrino’s default

NOTE: I prefer yarn over npm .

In few minutes your site will be up and running. You won’t need to do anything else.

|

|