Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Mike Hommey: Using C++ templates to prevent some classes of buffer overflows |

I recently found a small buffer overflow in Firefox’s SOCKS support, and came up with a nice-ish way to make it a C++ compilation error when it may happen with some template magic.

A simplfied form of the problem looks like this:

class nsSOCKSSocketInfo {

public:

nsSOCKSSocketInfo() : mData(new uint8_t[BUFFER_SIZE]) , mDataLength(0) {}

~nsSOCKSSocketInfo() { delete[] mData; }

void WriteUint8(uint8_t aValue) { mData[mDataLength++] = aValue; }

void WriteV5AuthRequest() {

mDataLength = 0;

WriteUint8(0x05);

WriteUint8(0x01);

WriteUint8(0x00);

}

private:

uint8_t* mData;

uint32_t mDataLength;

static const size_t BUFFER_SIZE = 2;

};

Here, the problem is more or less obvious: the third WriteUint8() call in WriteV5AuthRequest() will write beyond the allocated buffer size. (The real buffer size was much larger than that, and it was a different method overflowing, but you get the point)

While growing the buffer size fixes the overflow, that doesn’t do much to prevent a similar overflow from happening again if the code changes. That got me thinking that there has to be a way to do some compile-time checking of this. The resulting solution, at its core, looks like this:

template class Buffer {

public:

Buffer() : mBuf(nullptr) , mLength(0) {}

Buffer(uint8_t* aBuf, size_t aLength=0) : mBuf(aBuf), mLength(aLength) {}

Buffer WriteUint8(uint8_t aValue) {

static_assert(Size >= 1, "Cannot write that much");

*mBuf = aValue;

Buffer result(mBuf + 1, mLength + 1);

mBuf = nullptr;

mLength = 0;

return result;

}

size_t Written() { return mLength; }

private:

uint8_t* mBuf;

size_t mLength;

};

Then replacing WriteV5AuthRequest() with the following:

void WriteV5AuthRequest() {

mDataLength = Buffer(mData)

.WriteUint8(0x05)

.WriteUint8(0x01)

.WriteUint8(0x00)

.Written();

}

So, how does this work? The Buffer class is templated by size. The first thing we do is to create an instance for the complete size of the buffer:

Buffer(mData)

Then call the WriteUint8 method on that instance, to write the first byte:

.WriteUint8(0x05)

The result of that call is a Buffer (in our case, Buffer<1>) instance pointing to &mData[1] and recording that 1 byte has been written.

Then we call the WriteUint8 method on that result, to write the second byte:

.WriteUint8(0x01)

The result of that call is a Buffer (in our case, Buffer<0>) instance pointing to &mData[2] and recording that 2 bytes have been written so far.

Then we call the WriteUint8 method on that new result, to write the third byte:

.WriteUint8(0x00)

But this time, the Size template parameter being 0, it doesn’t match the Size >= 1 static assertion, and the build fails.

If we modify BUFFER_SIZE to 3, then the instance we run that last WriteUint8 call on is a Buffer<1> and we don’t hit the static assertion.

Interestingly, this also makes the compiler emit more efficient code than the original version.

Check the full patch for more about the complete solution.

|

|

Adam Lofting: Fundraising testing update |

I wrote a post over on fundraising.mozilla.org about our latest round of optimization work for our End of Year Fundraising campaign.

We’ve been sprinting on this during the Mozilla all-hands workweek in Portland, which has been a lot of fun working face-to-face with the awesome team making this happen.

You can follow along with the campaign, and see how were doing at fundraising.mozilla.org

And of course, we’d be over the moon if you wanted to make a donation.

These amazing people are working hard to build the web the world needs.

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/adamlofting/blog/~3/l32hZ-xKgeQ/

|

|

Nick Fitzgerald: Naming `Eval` Scripts With The `//# Sourceurl` Directive |

In Firefox 36, SpiderMonkey (Firefox's JavaScript engine) now supports the

//# sourceURL=my-display-url.js directive. This allows developers to give

a name to a script created by eval or new Function, and get better stack

traces.

To demonstrate this, let's use a minimal version of

John Resig's micro templater. The

micro templater compiles template strings into JS source code that it passes to

new Function, thus transforming the template string into a function.

function tmpl(str) {

return new Function("obj",

"var p=[],print=function(){p.push.apply(p,arguments);};" +

// Introduce the data as local variables using with(){}

"with(obj){p.push('" +

// Convert the template into pure JavaScript

str

.replace(/[\r\t\n]/g, " ")

.split(")[^\t]*)'/g, "$1\r")

.replace(/\t=(.*?)%>/g, "',$1,'")

.split("\t").join("');")

.split("%>").join("p.push('")

.split("\r").join("\'")

+ "');}return p.join('');");

};

The details of how the template is converted into JavaScript source code isn't

of import; what is important is that it dynamically creates new scripts via code

evaluated in new Function.

We can define a new templater function:

var hello = tmpl("Hello,

");

And use it like this:

hello({ name: "World!" });

// "Hello, World!

"

When we get an error, SpiderMonkey will generate a name for the evaled (or in

this case, new Functioned) script based on the location where the call to

eval (or new Function) occurred. For our concrete example, this is the

generated name for the hello templater function's frame:

file:///Users/fitzgen/scratch/foo.js line 2 > Function

And here it is in the context of an error with the whole stack trace:

hello({ name: Object.create(null) });

// TypeError: can't convert Object to string

// Stack trace:

// anonymous@file:///Users/fitzgen/scratch/foo.js line 2 > Function:1:107

// @file:///Users/fitzgen/scratch/foo.js:28:3

Despite being a solid improvement over just "eval frame" or something of that

sort, these stack traces can still be difficult to read. If there are many

different templater functions, the value of the eval script's introduction

location is further diminished. It is difficult to determine which of the many

functions created by tmpl contains the thrown error, because they all end up

with the same name, because they were all created at the same location.

We can improve this situation with the //# sourceURL directive.

Consider this version of the tmpl function adapted to use the //# sourceURL

directive:

function tmpl(name, str) {

return new Function("obj",

"var p=[],print=function(){p.push.apply(p,arguments);};" +

// Introduce the data as local variables using with(){}

"with(obj){p.push('" +

// Convert the template into pure JavaScript

str

.replace(/[\r\t\n]/g, " ")

.split(")[^\t]*)'/g, "$1\r")

.replace(/\t=(.*?)%>/g, "',$1,'")

.split("\t").join("');")

.split("%>").join("p.push('")

.split("\r").join("\'")

+ "');}return p.join('');"

+ "//# sourceURL=" + name);

};

Note that the function takes a new parameter called name and appends //#

sourceURL= to the end of the generated JS code passed to new Function.

With this new version of tmpl, we create our templater function like this:

var hello = tmpl("hello.template", "Hello

");

Now SpiderMonkey will use the name given by the //# sourceURL directive,

instead of using a name based on the introduction site of the script:

hello({ name: Object.create(null) });

// TypeError: can't convert Object to string

// Stack trace:

// anonymous@hello.template:1:107

// @file:///Users/fitzgen/scratch/foo.js:25:3

Giving the eval script a name makes it easier for us to debug errors originating from it, and we can give a different name to different scripts created at the same location.

The //# sourceURL directive is also particularly useful for dynamic code- and

module-loaders, which fetch source text over the network and then eval it.

Additionally, in Firefox 37, evaled sources with a //# sourceURL directive will be

debuggable and labeled with the name specified by the directive in the debugger.

|

|

Gregory Szorc: A Crazy Day |

Today was one crazy day.

The build peers all sat down with Release Engineering and Axel Hecht to talk l10n packaging. Mike Hommey has a Q1 goal to fix l10n packaging. There is buy-in from Release Engineering on enabling him in his quest to slay dragons. This will make builds faster and will pay off a massive mountain of technical debt that plagues multiple groups at Mozilla.

The Firefox build system contributors sat down with a bunch of Rust people and we talked about what it would take to integrate Rust into the Firefox build system and the path towards shipping a Rust component in Firefox. It sounds like that is going to happen in 2015 (although we're not yet sure what component will be written in Rust). I consider it an achievement that the gathering of both groups didn't result in infinite rabbit holing about system architectures, toolchains, and the build people telling horror stories to wide-eyed Rust people about the crazy things we have to do to build and ship Firefox. Believe me, the temptation was there.

People interested in the build system all sat down and reflected on the state of the build system and where we want to go. We agreed to create a build mode optimized for non-Gecko developers that downloads pre-built binaries - avoiding ~10 minutes of C/C++ compile time for builds. Mark my words, this will be one of those changes that once deployed will cause people to say "I can't believe we went so long without this."

I joined Mark C^ot'e and others to talk about priorities for MozReview. We'll be making major improvements to the UX and integrating static analysis into reviews. Push a patch for review and have machines do some of the work that humans are currently doing! We're tentatively planning a get-together in Toronto in January to sprint towards awesomeness.

I ended the day by giving a long and rambling presentation about version control, with emphasis on Mercurial. I can't help but feel that I talked way too much. There's just so much knowledge to cover. A few people told me afterwards they learned a lot. I'd appreciate feedback if you attended. Anyway, I got a few nods from people as I was saying some somewhat contentious things. It's always good to have validation that I'm not on an island when I say crazy things.

I hope to spend Friday chasing down loose ends from the week. This includes talking to some security gurus about another crazy idea of mine to integrate PGP into the code review and code landing workflow for Firefox. I'll share more details once I get a professional opinion on the security front.

|

|

Wladimir Palant: A systematic approach to MDN documentation? |

Note: This blog post started as a rant about MDN which is sadly not very useful for add-on authors way too often. I tried to reformulate it in a neutral way. The point definitely isn’t blaming the people working hard on keeping that documentation up to date.

MDN has some great content. However, as far as extension development goes, maybe somewhat less content and more structure/quality would be beneficial. Yes, there are a few well-written overview articles. But quite frankly, I’ve seen them for the first time today — because most of the time I’ll get to MDN via a search engine. And if you take this route, there is a good chance to hit an article that pre-dates Firefox 4.0.

Don’t believe me? Try searching for a guide to write XPCOM components. You are bound to hit this book written more than a decade ago. Not only is it horribly outdated, it explains how one would create such a component in C++ — something that is completely impracticable for extensions in current Firefox versions.

The next search hit is only marginally better. The examples here have been somewhat updated to work in recent Firefox versions. It starts by sending people to an extension which is compatible with Firefox 3.0. It then explains the scary details of defining your own interface — yet most developers simply want to implement an existing interface. And as if the original document wasn’t already crappy enough, somebody also added instructions on integrating the whole thing into the Mozilla build system — all that before the actually relevant stuff of course. You might also end up in this troubleshooting guide which used to be pretty helpful — five years ago.

In fact, XPCOM Changes in Gecko 2.0 seems to be the only piece of documentation with a complete explanation, starting with the code of the component itself and ending with the way it is registered via chrome.manifest. Not that this document is comprehensible, being primarily a list of changes. And of course, that’s a place where nobody will come looking.

Another example: JavaScript Debugger API. The old API (ugly but well-documented) has been removed from Firefox, taking a look at the new one is overdue. There is an easy to find JS Debugger API Guide, linking to a seemingly complete JS Debugger API Reference. Great, right? But it is incomplete and outdated. In particular, the most important piece of information for extensions is missing: how do I find the existing global objects?

And then there is a document called Debugger-API, confusingly placed under Firefox Developer Tools. It took a while for me to realize that it isn’t related to the debugger tool in Firefox, it’s rather an autogenerated documentation of the JavaScript Debugger API. And this one seems to be complete and current! “Autogenerated” here means that somebody from the SpiderMonkey team didn’t want to mess with the wiki syntax (cannot blame them) and put a bunch of Markdown files into the SpiderMonkey source tree instead — these were then imported into MDN.

This isn’t even about the long list of nice functionality that was implemented but never documented. Like the XPCOM iterator helpers introduced four years ago. Or a way to listen to all events. Or a way to apply user stylesheets to individual documents. Yes, the dev-doc-needed queue is very long and there is only so many people who contribute to MDN (besides, they would also need to understand the change).

So, how can this be solved? I see a few options:

- Marking documents as deprecated or obsolete isn’t sufficient, documents that aren’t useful need huge and very visible warnings at the very least. But frankly, why still keep them around?

- Mozilla has great technical writers but they clearly cannot keep up. That’s not really surprising given how much Mozilla has grown. Maybe developers who actually wrote the changes could help beyond setting the

dev-doc-neededflag? Sure, not everybody is a great writer. However, some documentation is already something that can be improved. - Some documents like the ones on XPCOM components and JavaScript modules can be checked automatically — a script can verify that the documented interface matches the current source code. If they don’t they can be flagged as needing an update (maybe even visible to MDN users and editors).

Anything else that can be done?

https://palant.de/2014/12/04/a-systematic-approach-to-mdn-documentation

|

|

Doug Belshaw: [IDEA] Webmaker Clubs: three legs to the stool |

Yesterday, during the Mozilla work week, some comments made by my colleagues made me think about Webmaker Clubs using a new metaphor. I tested it out in a few conversations and it didn’t get shot down, so I’m recording it here to come back to.

I thought about there being ‘three legs to the stool’ for Webmaker Clubs (name TBC):

- Web literacy

- Facilitation

- Pedagogy/ethos

The Web Literacy Map (currently v1.1 but soon v2.0) provides the basis for curriculum and learning pathways. We can build off this in a fairly straightforward way - and in fact Laura Hilliger has begun to do just that.

What I feel we need is some kind of 'map’ for the other two legs of the stool. What what this look like for facilitation skills? What about for pedagogy/ethos?

I was asked for clarity on pedagogy/ethos. It probably needs a better name, but all I mean here are the approaches to teaching and learning that work well in blended learning environments. What works well when you’re mentoring people both online and offline? Also, in terms of ethos, what do we mean by 'working open’?

If we went ahead with this approach we’d need to get the help of the community to help build it – as we do with the Web Literacy Map. The great thing is that if we did it right, we could provide a handbook that works in most situations. It would need to be generic enough to be applicable everywhere, but specific enough to guide new mentors.

Comments? Questions? Email me: doug@mozillafoundation.org

|

|

Pomax: Blogging during MozAllHandWorkWeek |

and I realised that I completely forgot to update gh-blog. Gah

|

|

Yunier Jos'e Sosa V'azquez: Mozilla lanzar'a Firefox para iOS |

Con el lanzamiento de iOS 8 y los primeros pasos para una apertura de Apple a los navegadores que no usan Webkit como motor de renderizado, y despu'es de haber anunciado que no lanzar'ian una versi'on de Firefox para ese sistema, Mozilla ha cambiado su postura y entrar'a en iOS.

La principal causa por la que Mozilla decidi'o no entrar a iOS fue porque Apple impon'ia una serie de restricciones a navegadores de terceros, como por ejemplo: no pod'ian ser el navegador por defecto. Adem'as, imped'ia que los desarrolladores pudieran incluir sus propios motores de Javascript, haciendo que susnavegadores fueran m'as lentos que Safari. Pero con el arribo de Javascript Nitro Engine en iOS 8 la situaci'on ha cambiado para bien de todos y muestra una apertura de Apple con respecto al tema.

El anuncio fue realizado por Jonathan Nightingale VP de Firefox y compartido por Lukas Blakk, Jefe de lanzamientos de Firefox en su cuenta en Twitter mientras realizaban un evento interno. “Necesitamos estar donde nuestros usuarios est'an, por eso vamos a llevar a Firefox a iOS”

Hace poco fue anunciado oficialmente esa postura y han dicho:

En Mozilla, ponemos al usuario de primero y queremos ofrecer una opci'on independiente para ellos en cualquier plataforma. Estamos en las etapas iniciales de experimentaci'on con algo que permita a los usuarios de iOS poder elegir Firefox.

Estamos experimentando con un par de conceptos diferentes y cuando tengamos m'as, lo compartiremos.

Ahora, todas aquellas personas que usen iOS podr'an contar con las caracter'isticas que ofrece Firefox y acabar'an ganando al poder elegir entre varios navegadores dentro del ecosistema.

Fuentes: Mac Rumor, Applesfera, Mozilla Press Center

http://firefoxmania.uci.cu/mozilla-lanzara-firefox-para-ios/

|

|

Naoki Hirata: Question on being Open… |

One of the things I am grateful for in working for Mozilla is the opportunity to learn.

Recently through various channels, I’ve learned about values, trust and integrity. (Side note: I highly recommend the book that I am currently reading : The Speed of Trust)

Values are highly important to people and the company/culture. ( Side note: I also found that for those that throw away the very value that they are trying to protect at all cost will find themselves very miserable. )

Maybe I am dumb; I don’t understand a few things still though and I need help understanding it after even having worked 4 years at the company. These are the top two things that still cause me to wonder:

1) How does one stay open about protecting privacy/IP and how can we protect privacy/IP and still be open? And without being miserable?

2) How do we stay open in a fast moving environment where we’re constantly busy? The context of this is that I had been talking to a few coworkers and when we were talking, I happened to tell them something they weren’t aware of. The expression “oh I wish I knew that sooner” was stated. Blogs and emails can be missed often, and in some people’s cases skipped from being read; miss a meeting and you won’t hear about it. Asking around and trying to get the source of truth sometimes is hard and doesn’t scale, etc. etc. Everyone has a different way of working it seems… how do you get the source of truth and maintain doing the work load of going faster?

Filed under: Planet, QMO Tagged: Planet, QMO

http://shizen008.wordpress.com/2014/12/04/question-on-being-open/

|

|

Gregory Szorc: The Mozlandia Tree Outage and Code Review |

You may have noticed the Firefox trees were closed for the better part of yesterday.

Long story short, a file containing URLs for Firefox installers was updated to reference https://ftp.mozilla.org/ from http://download-installer.cdn.mozilla.net/. The original, latter host is a CDN. The former is not. When thousands of clients started hitting ftp.mozilla.org, it overwhelmed the servers and network, causing timeouts and other badness.

The change in question was accidental. It went through code review. From a code change standpoint, procedures were followed.

It is tempting to point fingers at the people involved. However, I want us to consider placing blame elsewhere: on the code review tool.

The diff being reviewed was to change the Firefox version number from 32.0 to 32.0.3. If you were asked to review this patch, I'm guessing your eyes would have glanced over everything in the URL except the version number part. I'm pretty sure mine would have.

Let's take a look at what the reviewer saw in Bugzilla/Splinter (click to see full size):

And here is what the reviewer would have seen had the review been conducted in MozReview:

Which tool makes the change of hostname more obvious? Bugzilla/Splinter or MozReview?

MozReview's support for intraline diffs more clearly draws attention to the hostname change. I posit that had this patch been reviewed with MozReview, the chances are greater we wouldn't have had a network outage yesterday.

And it isn't just intraline diffs that make Splinter/Bugzilla a sub-optimal code review tool. I recently blogged about the numerous ways that using Bugzilla for code revie results in harder reviews and buggier code. Every day we continue using Bugzilla/Splinter instead of investing in better code review tools is a day severe bugs like this can and will slip through the cracks.

If there is any silver lining to this outage, I hope it is that we need to double down on our investment in developer tools, particularly code review.

http://gregoryszorc.com/blog/2014/12/04/the-mozlandia-tree-outage-and-code-review

|

|

Nigel Babu: A Funny Bug |

Yesterday, we had a 6-hour long tree-closure. From 11:48 am PST to 16:43 pm PST. Philor closed the trees when he noticed the issue. By the time I noticed it, it was much later and luckily, I was in a room with the A-team and Releng. I walked over to catlee and nthomas. They both took a look and we were trying to figure out the problem. Wes and Ryan were helping me later and we just called rail and [mrrrgn][morgan] over to help us sort it out. This is much better than IRC!

Couple of confounding things at that point - It was happening across trees, and it didn’t feel like a code issue. However, Releng are all here and haven’t landed any changes. Morgan and rail identified the problem pretty soon. We were deleting temp files on AWS machines as well instead of only on SCL3 machines. Among the temp files we deleted were pulseaudio files. Deleting these files will break pulseaudio.

Now the funny thing about this bug. We ran into it only now because we had so few commits. Let me say that again, we triggered a bug in the automation because we had so few commits. That is hilarious, probably in a gallows humor kind of way.

|

|

Mic Berman: Using Values as a Foundation to Build your Company to Last |

I recently gave a presentation at MarsDD on how to use your values as a founder or CEO to build your organization to last. I cover what values are and which key processes must incorporate your values to ensure you can build great teams, enable decision making at your organizations edges ie next layers down from founders and leadership teams, retain and engage great talent, and scale to meet your growth.

here it is :)

|

|

Lucas Rocha: New tablet UI for Firefox on Android |

The new tablet UI for Firefox on Android is now available on Nightly and, soon, Aurora! Here’s a quick overview of the design goals, development process, and implementation.

Design & Goals

Our main goal with the new tablet UI was to simplify the interaction with tabs—read Yuan Wang’s blog post for more context on the design process.

In 36, we focused on getting a solid foundation in place with the core UI changes. It features a brand new tab strip that allows you to create, remove and switch tabs with a single tap, just like on Firefox on desktop.

The toolbar got revamped with a cleaner layout and simpler state changes.

Furthermore, the fullscreen tab panel—accessible from the toolbar—gives you a nice visual overview of your tabs and sets the stage for more advanced features around tab management in future releases.

Development process

At Mozilla, we traditionally work on big features in a separate branch to avoid disruptions in our 6-week development cycles. But that means we don’t get feedback until the feature lands in mozilla-central.

We took a slightly different approach in this project. It was a bit like replacing parts of an airplane while it’s flying.

We first worked on the necessary changes to allow the app to have parallel UI implementations in a separate branch. We then merged the new code to mozilla-central and did most of the UI development there.

This approach enabled us to get early feedback in Nightly before the UI was considered feature-complete.

Implementation

In order to develop the new UI directly in mozilla-central, we had to come up with a way to run either the old or the new tablet UIs in the same build.

We broke up our UI code behind interfaces with multiple concrete implementations for each target UI, used view factories to dynamically instantiate parts of the UI, prefixed overlapping resources, and more.

The new tab strip uses the latest stable release of TwoWayView which got a bunch of important bug fixes and couple of new features such as smooth scroll to position.

Besides improving Firefox’s UX on Android tablets, the new UI lays the groundwork for some cool new features. This is not a final release yet and we’ll be landing bug fixes until 36 is out next year. But you can try it now in our Nightly builds. Let us know what you think!

http://lucasr.org/2014/12/03/new-tablet-ui-for-firefox-on-android/

|

|

Kim Moir: Mozilla pushes - November 2014 |

Trends

Not a record breaking month, in fact we are down over 2000 pushes since the last month.

Highlights

10376 pushes

346 pushes/day (average)

Highest number of pushes/day: 539 pushes on November 12

17.7 pushes/hour (average)

General Remarks

Try keeps had around 38% of all the pushes, and gaia-try has about 30%. The three integration repositories (fx-team, mozilla-inbound and b2g-inbound) account around 23% of all the pushes.

Records

August 2014 was the month with most pushes (13,090 pushes)

August 2014 has the highest pushes/day average with 422 pushes/day

July 2014 has the highest average of "pushes-per-hour" with 23.51 pushes/hour

October 8, 2014 had the highest number of pushes in one day with 715 pushes

http://relengofthenerds.blogspot.com/2014/12/mozilla-pushes-november-2014.html

|

|

Jeff Walden: Working on the JS engine, Episode V |

From a stack trace for a crash:

20:12:01 INFO - 2 libxul.so!bool js::DependentAddPtr, js::StackBaseShape, js::SystemAllocPolicy> >::add, js::UnownedBaseShape*>(js::ExclusiveContext const*, js::HashSet, js::StackBaseShape, js::SystemAllocPolicy>&, JS::RootedGeneric const&, js::UnownedBaseShape* const&) [HashTable.h:3ba384952a02 : 372 + 0x4]

If you can figure out where in that mess the actual method name is without staring at this for at least 15 seconds, I salute you. (Note that when I saw this originally, it wasn’t line-wrapped, making it even less readable.)

I’m not sure how this could be presented better, given the depth and breadth of template use in the class, in the template parameters to that class, in the method, and in the method arguments here.

http://whereswalden.com/2014/12/03/working-on-the-js-engine-episode-v/

|

|

Wladimir Palant: Dumbing down HTML content for AMO |

If you are publishing extensions on AMO then you might have the same problem: how do I keep content synchronous between my website and extension descriptions on AMO? It could have been simple: take the HTML code from your website, copy it into the extension description and save. Unfortunately, usually this won’t produce useful results. The biggest issue: AMO doesn’t understand HTML paragraphs and will strip them out (along with most other tags). Instead it will turn each line break in your HTML code into a hard line break.

Luckily, a fairly simple script can do the conversion and make sure your text still looks somewhat okayish. Here is what I’ve come up with for myself:

#!/usr/bin/env python import sys import redata = sys.stdin.read()# Normalize whitespace data = re.sub(r'\s+', ' ', data)# Insert line breaks after block tags data = re.sub(r'<(ul|/ul|ol|/ol|blockquote|/blockquote|/li)\b[^<>]*>\s*', '<\\1>\n', data)# Headers aren't supported, turn them into bold text data = re.sub(r']*>(.*?)\s*', '\\2\n\n', data)# Convert paragraphs into line breaks data = re.sub(r']*>\s*', '', data) data = re.sub(r'\s*', '\n\n', data)# Convert hard line breaks into line breaks data = re.sub(r']*>\s*', '\n', data)# Remove any leading or trailing whitespace data = data.strip()print data

This script expects the original HTML code from standard input and will print the result to standard output. The conversions performed are sufficient for my needs, your mileage may vary — e.g. because you aren’t closing paragraph tags or because relative links are used that need resolving. I’m not intending to design some universal solution, you are free to add more logic to the script as needed.

Edit: Alternatively you can use the equivalent JavaScript code:

var textareas = document.getElementsByTagName("textarea"); for (var i = 0; i < textareas.length; i++) { if (window.getComputedStyle(textareas[i], "").display == "none") continue;data = textareas[i].value;// Normalize whitespace data = data.replace(/\s+/g, " ");// Insert line breaks after block tags data = data.replace(/<(ul|\/ul|ol|\/ol|blockquote|\/blockquote|\/li)\b[^<>]*>\s*/g, "<$1>\n");// Headers aren't supported, turn them into bold text data = data.replace(/]*>(.*?)<\/h\1>\s*/g, "$2\n\n");// Convert paragraphs into line breaks data = data.replace(/]*>\s*/g, ""); data = data.replace(/<\/p>\s*/g, "\n\n");// Convert hard line breaks into line breaks data = data.replace(/]*>\s*/, "\n");// Remove any leading or trailing whitespace data = data.trim();textareas[i].value = data; }

This one will convert the text in all visible text areas. You can either run it on AMO pages via Scratchpad or turn it into a bookmarklet.

https://palant.de/2014/12/03/dumbing-down-html-content-for-amo

|

|

Yunier Jos'e Sosa V'azquez: Privacy Coach para Android |

Firefox para Android te pone m'as f'acil que nunca tener control sobre tu privacidad en el m'ovil. Instala Privacy Coach, el nuevo complemento de Firefox que te ayudar'a a entender las opciones de privacidad para cookies, rastreo, navegaci'on como invitado y mucho m'as.

Privacy Coach te brinda una vista general de todas las caracter'isticas relacionadas con la privacidad y sus beneficios para ti. Tambi'en te permite ir inmediatamente a cada configuraci'on de la funcionalidad y hacerla corresponder a tus experiencias de navegaci'on. Ayud'andote a escoger las opciones que se adecuan mejor a ti, y todo esto desde un conveniente y 'unico lugar en tu Firefox para Android.

Mozilla tiene una larga historia de darte el control de tu privacidad, esto est'a incluido en todos sus productos y en su misi'on para hacer una Web m'as abierta, m'as transparente y segura para todos. Aprende m'as acerca de c'omo Mozilla y Firefox protegen tu privacidad en https://www.mozilla.org/en-US/privacy/you/.

Instalar Privacy Coach (s'olo para Android).

|

|

Tantek Celik: Why An Open Source Comms OS (Like @FirefoxOS) Matters |

This morning I tried to install "Checky" on my iPod 5 Touch and was rejected.

An app that tracks how often you check your mobile device should work regardless of how connected you are or not. From experience I know it is plenty easy to be distracted by apps and such on an iPod touch.

Secondly, I saw this article on GigaOM: Hope you like iOS 8.1.1, because there’s no going back

Apple has made it technically impossible for most people to install an older version of iOS on iPhones, iPads and iPod touch devices

Which links to this article: Apple closes iOS 8.1 signing window, eliminating chance to downgrade

Apple has closed the signing window for iOS 8.1 on compatible iPhone, iPad and iPod touch models, thereby eliminating the ability for users to downgrade to the software version

There's an expectation when you buy a computer, tablet, or mobile device, that if all else goes wrong (or you want to sell it to someone), you can always reinstall the OS it came from and be on your way.

Or if a software update has a bad regression (a bug in something that used to work fine), the user has the ability to revert to the previous version.

However if you're an iOS device user, you're out of luck. Apple now requires iOS 8.1.1 on your iOS device(s).

This is not a theoretical problem. iOS8 broke facetime: URLs. In particular, if you're running iOS8 (any version thru 8.1.1), and you tap on a facetime: URL with a destination to dial, it will prompt you, then open Facetime, and then do nothing.

What worked fine in iOS7: tapping on a facetime: URL prompts you to make sure you want to call that person, and then launches the Facetime application directly into starting a conversation with that person.

That facetime: URL scheme is proprietary to Apple. No one else uses it. And they broke it. It's one of the URLs in the URLs For People Focused Mobile Communication.

I've deliberately refrained from upgrading to iOS8 for this reason alone. If Apple regressed with such a simple and obvious bug, what other less obvious bugs did they ship iOS8 with?

Contrast this with open source alternatives like FirefoxOS.

You as the user should be in control. If you want to (re)install the original software that your device came with, you should be able to.

The hope is that with an open source alternative, users will have that choice, rather than being locked in, and prevented from returning their devices to the factory settings that they came with.

http://tantek.com/2014/336/b1/why-open-source-comms-os-matters

|

|

Mike Hommey: Logging Firefox memory allocations |

A couple years ago, when I was actively working on integrating jemalloc 3 in the Firefox build, and started investigating some memory usage regression compared to our old fork, I came up with a replace-malloc library for Firefox that would log all the allocations, and allow to replay them in a more consistent (and faster) way in a separate program, such that testing different configurations of jemalloc with the same workload can be streamlined.

A couple weeks ago, I refreshed that work, and made it work on all the tier-1 Firefox desktop platforms. That work is now in the tree instead of on my hard drive, and will allow us to test the effects of jemalloc changes in a better way.

The bulk of how to use this feature is the following:

- Start Firefox with the following environment variables:

- on Linux:

LD_PRELOAD=/path/to/memory/replace/logalloc/liblogalloc.so - on Mac OSX:

DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES=/path/to/memory/replace/logalloc/liblogalloc.dylib - on Windows:

MOZ_REPLACE_MALLOC_LIB=/path/to/memory/replace/logalloc/logalloc.dll - on all the above:

MALLOC_LOG=/path/to/log-file

- on Linux:

- Play your workload in Firefox, then close it.

- Run the following command to prepare the log file for replay:

python /source/path/to/memory/replace/logalloc/replay/logalloc_munge.py < /path/to/log-file > /path/to/replay.log - Replay the logged allocations with the following command:

/path/to/memory/replace/logalloc/replay/logalloc-replay < /path/to/replay.log

More information and implementation details can be found in the README accompanying the code for that functionality.

|

|

Mike Hommey: Mozilla Build System: past, present and future |

The Mozilla Build System has, for most of its history, not changed much. But, for a couple years now, we’ve been, slowly and incrementally, modifying it in quite extensive ways. This post summarizes the progress so far, and my personal view on where we’re headed.

Recursive make

The Mozilla Build System has, all along, been implemented as a set of recursively traversed Makefiles. The way it has been working for a very long time looks like the following:

- For each tier (group of source directories) defined at the top-level:

- For each subdirectory in current tier:

- Build the

exporttarget recursively for each subdirectory defined in Makefile. - Build the

libstarget recursively for each subdirectory defined in Makefile.

- Build the

- For each subdirectory in current tier:

The typical limitation due to the above is that some compiled tests from a given directory would require a library that’s not linked until after the given directory is recursed, so another target was later added on top of that (tools).

There was not much room for parallelism, except in individual directories, where multiple sources could be built in parallel, but never would sources from multiple directories be built at the same time. So, for a bunch of directories where it was possible, special rules were added to allow that to happen, which led to interesting recursions:

- For each of

export,libs, andtools:- Build the target in the subdirectories that can be built in parallel.

- Build the target in the current directory.

- Build the target in the remaining subdirectories.

This ensured some extra fun with dependencies between (sub)directories.

Apart from the way things were recursed, all sorts of custom build rules had piled up, some of which relied on things in other directories having happened beforehand, and the build system implementation itself relied on some quite awful things (remember allmakefiles.sh?)

Gradual Overhaul

Around two years ago, we started a gradual overhaul of the build system.

One of the goals was to move away from Makefiles. For various reasons, we decided to go with our own kind-of-declarative (but really, sandboxed python) format (moz.build) instead of using e.g. gyp. The more progress we make on the build system, and the more I think this was the right choice.

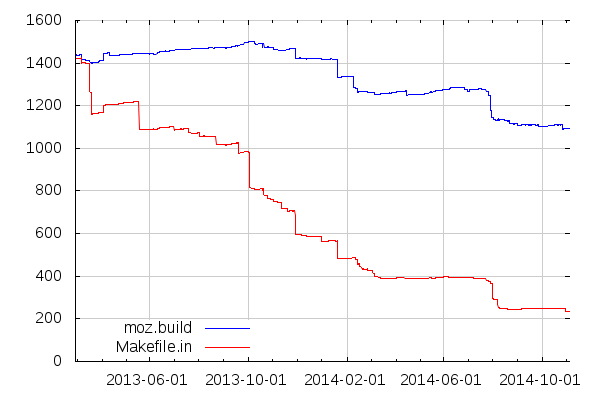

Anyways, while we’ve come a long way and converted a lot of Makefiles to moz.build, we’re not quite there yet:

One interesting thing to note in the above graph is that we’ve also been reducing the overall number of moz.build files we use, by consolidating some declarations. For example, some moz.build files now declare source or test files from their subdirectories directly, instead of having one file per directory declare sources and test files local to their own directory.

Pseudo derecursifying recursive Make

Neologism aside, one of the ideas to help with the process of converting the build system to something that can be parallelized more massively was to reduce the depth of recursion we do with Make. So that instead of a sequence like this:

- Entering directory A

- Entering directory A/B

- Leaving directory A/B

- Entering directory A/C

- Entering directory A/C/D

- Leaving directory A/C/D

- Entering directory A/C/E

- Leaving directory A/C/E

- Entering directory A/C/F

- Leaving directory A/C/F

- Leaving directory A/C

- Entering directory A/G

- Leaving directory A/G

- Leaving directory A

- Entering directory H

- Leaving directory H

We would have a sequence like this:

- Entering directory A

- Leaving directory A

- Entering directory A/B

- Leaving directory A/B

- Entering directory A/C

- Leaving directory A/C

- Entering directory A/C/D

- Leaving directory A/C/D

- Entering directory A/C/E

- Leaving directory A/C/E

- Entering directory A/C/F

- Leaving directory A/C/F

- Entering directory A/G

- Leaving directory A/G

- Entering directory H

- Leaving directory H

For each directory there would be a directory-specific target per top-level target, such as A/B/export, A/B/libs, etc. Essentially those targets are defined as:

%/$(target): $(MAKE) -C $* $(target)

And each top-level target is expressed as a set of dependencies, such as, in the case above:

A/B/libs: A/libs A/C/libs: A/B/libs A/C/D/libs: A/C/libs A/C/E/libs: A/C/D/libs A/C/F/libs: A/C/E/libs A/G/libs: A/C/F/libs H/libs: A/G/libs libs: H/libs

That dependency list, instead of being declared manually, is generated from the “traditional” recursion declaration we had in moz.build, through the various *_DIRS variables. I’ll skip the gory details about how this replicated the weird subdirectory orders I mentioned above when you had both PARALLEL_DIRS and DIRS. They are irrelevant today anyways.

You’ll also note that this also removed the notion of tier, and the entirety of the tree is dealt with for each target, instead of iterating all targets for each group of directories.

[But note that, confusingly, but for practical reasons related to the amount of code changes required, and to how things were incrementally set in place, those targets are now called tiers]

From there, parallelizing parts of the build only involves reorganizing those Make dependencies such that Make can go in several subdirectories at once, the ultimate goal being:

libs: A/libs A/B/libs A/C/libs A/C/D/libs A/C/E/libs A/C/F/libs A/G/libs A/H/libs

But then, things in various directories may need other things built in different directories first, such that additional dependencies can be needed, for example:

A/B/libs A/C/libs: A/libs A/H/libs: A/G/libs

The trick is that those dependencies can in many cases be deduced from the contents of moz.build. That’s where we are today, for example, for everything related to compilation: We added a compile target that deals with everything C/C++ compilation, and we have dependencies between directories building objects and directories building libraries and executables that depend on those objects. You can have a taste yourself:

$ mach clobber $ mach configure $ mach build export $ mach build -C / toolkit/library/target

[Note, the compile target is actually composed of two sub-targets, target and host.]

The third command runs the export target on the whole tree, because that’s a prerequisite that is not expressed as a make dependency yet (it would be too broad of a dependency anyways).

The last command runs the toolkit/library/target target at the top level (as opposed to mach build toolkit/library/target, which runs the target target in the toolkit/library directory). That will build libxul, and everything needed to link it, but nothing else unrelated.

All the other top-level targets have also received this treatment to some extent:

- The

exporttarget was made entirely parallel, although it keeps some cross-directory dependencies derived from the historical traversal data. - The

libstarget is still entirely sequential, because of all the horrible rules in it that may or may not depend on the historical traversal order. - A parallelized

misctarget was recently created to receive all the things that are currently done as part of thelibstarget that are actually safe to be parallelized (another reason for creating this new target is thatlibsis now a misnomer, since everything related to libraries is now part ofcompile). Please feel free to participate in the effort to movelibsrules there. - The

toolstarget is still sequential, but see below.

Although, some interdependencies that can’t be derived yet are currently hardcoded in config/recurse.mk.

And since the mere fact of entering a directory, figuring out if there’s anything to do at all, and leaving a directory takes some time on builds when only a couple things changed, we also skip some directories entirely by making them not have a directory/target target at all:

exportandlibsonly traverse directories where there is aMakefile.infile, or where themoz.buildfile sets variables that do require something to be done in those targets.compileonly traverses directories where there is something to compile or link.misconly traverses directories with an explicitHAS_MISC_RULE = Truewhen they have aMakefile.in, or with amoz.buildsetting variables affecting themisctarget.toolsonly traverses directories that contain a Makefile.in containingtools::(there’s actually a regexp, but in essence, that’s it).

Those skipping rules allow to only traverse, taking numbers from a local Linux build, as of a couple weeks ago:

- 186 directories during

libs, - 472 directories during

compile, - 161 directories during

misc, - 382 directories during

libs, - 2 directories during

tools.

instead of 850 for each.

In the near future, we may want to change export and libs to opt-ins, like misc, instead of opt-outs.

Alternative build backends

With more and more declarations in moz.build, files, we’ve been able to build up some alternative build backends for Eclipse and Microsoft Visual Studio. While they still are considered experimental, they seem to work well enough for people to take advantage of them in some useful ways. They however still rely on the “traditional” Make backend to build various things (to the best of my knowledge).

Ultimately, we would like to support entirely different build systems such as ninja or tup, but at the moment, many things still heavily rely on the “traditional” Make backend. We’re getting close to having everything related to compilation available from the moz.build declarations (ignoring third-party code, but see further below), but there is still a long way to go for other things.

In the near future, we may want to implement hybrid build backends where compilation would be driven by ninja or tup, and the rest of the build would be handled by Make. However, my feeling is that the Make backend is fast enough for compilation and ninja doesn’t bring enough other than performance that it’s not worth investing in a ninja backend. Tup is different because it does solve some of the problems with incremental builds.

While on the topic of being close to having everything related to compilation available from moz.build declarations, closing in on this topic would allow, more than such hybrid build systems, to better integrate tools such as code static analyzers.

Unified C/C++ sources

Compiling C code, and even more compiling C++ code, involves reading the same headers an important number of times. In C++, that usually also means instantiating the same templates and compiling the same inline methods numerous times.

So we’ve worked around this by creating “unified sources” that just #include the actual source files, grouping them 16 by 16 (except when specified otherwise).

This reduced build times drastically, and, interestingly, reduced the size of DWARF debugging symbols as well. This does have a couple downsides, though. It allows #include impurity in the code in such a way that e.g. changes in the file groups can lead to subtle build failures. It also makes incremental builds significantly slower in parts of the tree where compiling one file is already somehow slow, so doing 16 at a time can be a drag for people working on that code. This is why we’re considering decreasing the number for the javascript engine in the near future. We should probably investigate where else building one unified source is slow enough to be a concern. I don’t think we can rely on people actively complaining about it, they’ve been too used to slow build times to care to file bugs about it.

Relatedly, our story with #include is suboptimal to say the least, and several have been untangled, but there’s still a long tail. It’s a hard problem to solve, even with tools like IWYU.

Fake libraries

For a very long time, the build system was building intermediate static libraries, and then was linking them together to form shared libraries. This is how the main components were built in the old days before libxul (remember libgklayout?), and was how libxul built when it was created. For various reasons, ranging from disk space waste to linker inefficiencies, this was replaced by building fake libraries, that only reference the objects that would normally be contained in the static library that used to be built. This later was changed to use a more complex system allowing more flexibility.

Fast-forward to today, and with all the knowledge from moz.build, one of the usecases of that more complex system was made moot, and in the future, those fake libraries could be generated as build backend files instead of being created during the build.

Specialized incremental builds

When iterating C/C++ code patches, one usually needs to (re)compile often. With the build system having the overhead it has, and rebuilding with no change taking many seconds (it has been around a minute for a long time on my machine and is now around half of that, although, sadly, I had got it down to 20 seconds but that regressed recently, damn libs rules), we also added a special rule that only handles header changes and rebuilding objects, libraries and executables.

That special rule is invoked as:

$ mach build binaries

And takes about 3.5s on my machine when there are no changes. It used to be faster thanks to clever tricks, but that was regressed on purpose. That’s a trade-off, but linking libxul, which most code changes require, takes much longer than that anyways. If deemed necessary, the same clever tricks could be restored.

While we work to improve the overall build experience, in the near future we should have one or more special rules for non-compilation use-cases. For Firefox frontend developers, the following command may do part of the job:

$ mach build -C / chrome

but we should have some better and more complete commands for them and e.g. Firefox Android developers.

We also currently have a build option allowing to entirely skip everything that is compilation related (--disable-compile-environment), but it is currently broken and is only really useful in few use cases. In the near future, we need build modes that allow to use e.g. nightly builds as if they were the result of compiling C++ source. This would allow some classes of developers to skip compilations altogether, which are an unnecessary overhead for them at the moment, since they need to compile at least once (and with all the auto-clobbers we have, it’s much more than that).

Localization

Related to the above, the experience of building locale packs and repacks for Firefox is dreadful. Even worse than that, it also relies on a big pile of awful Make rules. It probably is, along with the code related to the creation of Firefox tarballs and installers, the most horrifying part of the build system. Its entanglement with release automation also makes improving the situation unnecessarily difficult.

While there are some sorts of tests running on every push, there are many occasions where those tests fail to catch regressions that lead to broken localized builds for nightlies, or worse on beta or release (which, you’ll have to admit, is a sadly late a moment to find such regressions).

Something really needs to be done about localization, and hopefully the discussions we’ll have this week in Portland will lead to improvements in the short to medium term.

Install manifests

The build system copies many files during the build. From the source directory to the “object” directory. Sometimes in $(DIST)/somedir, sometimes elsewhere. Sometimes in both or more. On non-Windows systems, copies are replaced by symbolic links. Sometimes not. There are also files that are preprocessed during the build.

All those used to be handled by Make rules invoking $(NSINSTALL) on every build. Even when the files hadn’t changed. Most of these were replaced by some Makefile magic, but many are now covered with so-called “install manifests”.

Others, defined in jar.mn files, used to be added to jar files during the build. While those jars are not created anymore because of omni.ja, the corresponding content is still copied/symlinked and defined in jar.mn.

In the near future, all those should be switched to install manifests somehow, and that is greatly tied to solving part of the localization problem: currently, localization relies on Make overrides that moz.build can’t know about, preventing install manifests being created and used for the corresponding content.

Faster configure

One of the very first things the build system does when a build starts from scratch is to run configure. That’s a part of the build system that is based on the antiquated autoconf 2.13, with 15+ years of accumulated linear m4 and shell gunk. That’s what detects what kind of compiler you use, how broken it is, how broken its headers are, what options you requested, what application you want to build, etc.

Topping that, it also invokes configure from third-party software that happen to live in the tree, like ICU or jemalloc 3. Those are also based on autoconf, but in more recent versions than 2.13. They are also third-party, so we’re essentially only importing them, as opposed to actively making them bigger for those that are ours.

While it doesn’t necessarily look that bad when running on e.g. Linux, the time it takes to run all this pile of shell scripts is painfully horrible on Windows (like, taking more than 5 minutes on automation). While there’s still a lot to do, various improvements were recently made:

- Some classes of changes (such as modifying

configure.in) make the build system re-runconfigure. It used to trigger everyconfigureto run again, but now only re-runs a relevant subset. - They used to all run sequentially, but apart from the top-level one, which still needs to run before all the others, they now all run in parallel. This cut

configuretimes almost in half on Windows clobber builds on automation.

In the future, we want to get rid of autoconf 2.13 and use smart lazy python code to only run the tests that are relevant to the configure options. How this would all exactly work has, as of writing, not been determined. It’s been on my list of things to investigate for a while, but hasn’t reached the top. In the near future, though, I would like to move all our autoconf code related to the build toolchain (compiler and linker) to some form of python code.

Zaphod beeblebuild

There are essentially two main projects in the mozilla-central repository: Firefox/Gecko and the Javascript engine. They use the same build system in many ways. But for a very long time, they actually relied on different copies of the same build system files, like config/rules.mk or build/autoconf/*.m4. And we had a check-sync-dirs script verifying that both projects were indeed using the same file contents. Countless times, we’ve had landings forgetting to synchronize the files and leading to a check-sync-dirs error during the build. I plead guilty to have landed such things multiple times, and so did many other people.

Those days are now long gone, but we currently rely on dirty tricks that still keep the Firefox/Gecko and Javascript engine build systems half separate. So we kind of replaced a conjoined-twins system with a biheaded system. In the future, and this is tied to the section above, both build systems would be completely merged.

Build system interface

Another goal of the build system changes was to make the build and test experience better. Especially, running tests was not exactly the most pleasant experience.

A single entry point to the build system was created in the form of the mach tool. It simplifies and self-documents many of the workflows that required arcane knowledge.

In the future, we will deprecate the historical build system entry points, or replace their implementation to call mach. This includes client.mk and testing/testsuite-targets.mk.

moz.build

Yet another goal of the build system changes was to improve the experience developers have when adding code to the tree. Again, while there is still a lot to be done on the subject, there have been a lot of changes in the past year that I hope have made developer’s lives easier.

As an example, adding new code to libxul previous required:

- Creating a

Makefile.infile- Defining a

LIBRARY_NAME. - Defining which sources to build with

CPPSRCS,CSRCS,CMMSRCS,SSRCSorASFILES, using the right variable name for the each source type (C++ or C or Obj-C, or assembly. By the way, did you know there was a difference betweenSSRCSandASFILES?).

- Defining a

- Adding something like

SHARED_LIBRARY_LIBS += $(call EXPAND_LIBNAME_PATH,libname,$(DEPTH)/path)totoolkit/library/Makefile.in.

Now, adding new code to libxul requires:

- Creating a

moz.buildfile- Defining which sources to build with

SOURCES, whether they are C, C++ or other. - Defining

FINAL_LIBRARYto'xul'.

- Defining which sources to build with

This is only a simple example, though. There are more things that should have gotten easier, especially since support for templates landed. Templates allowed to hide some details such as dependencies on the right combination of libxul, libnss, libmozalloc and others when building programs or XPCOM components. Combined with syntactic sugar and recent changes to how moz.build data is handled by build backends, we could, in the future, allow to define multiple targets in a single directory. Currently, if you want to build e.g. a library and a program or multiple libraries in the same directory, well, essentially, you can’t.

Relatedly, moz.build currently suffers from how it was grown from simply moving definitions from Makefile.in., and how those definitions in Makefile.in were partly tied to how Make works, and how config.mk and rules.mk work. Consolidating CPPSRCS, CSRCS and other variables into a single SOURCES variable is something that should be done more broadly, and we should bring more consistency to how things are defined (for example NO_PGO vs. no_pgo depending on the context, etc.). Incidentally, I think those changes can be made in a way that simplifies the build backend python code.

Multipass

Some build types, while unusual for developers to do locally on their machine, happen regularly on automation, and are done in awful or inefficient ways.

First, Profile Guided Optimized (PGO) builds. The core idea for those builds is to build once with instrumentation, run the resulting instrumented binary against a profile, and rebuild with the data gathered from that. In our build system, this is what actually happens on Linux:

- Build everything with instrumentation.

- Run instrumented binary against profile.

- Remove half the object directory, including many non-compiled code things that are generated during a normal build.

- Rebuild with optimizations guided by the collected data.

Yes, the last step repeats things from the second that are not necessary to be repeated.

Second, Mac universal builds, which happen in the following manner:

- Build everything for i386.

- Build everything for x86-64.

- Merge the result of both builds.

Yes, “everything” in both “Build everything” includes the same non-compiled files. Then the third step checks that those non-compiled files actually match (and for buildconfig.html, has special treatment) and merges the i386 and x86-64 binaries in Mach-o fat binaries. Not only is this inefficient, but the code behind this is terrible, although it got better with the new packager code. And reproducing universal builds locally is not an easy task.

In the future, the build system would be able to compile binaries for different targets in a way that doesn’t require jumping through hoops like the above. It could even allow to build e.g. a javascript shell for the build machine during a cross-compilation for Android without involving wrapper scripts to handle the situation.

Third party code

Building Firefox involves building several third party libraries. In some cases, they use gyp, and we convert their gyp files to moz.build at import time (angle, for instance). In other cases, they use gyp, and we just use those gyp files through moz.build rules, such that the gyp processing is done during configure instead of at import time (webrtc). In yet other cases, they use autoconf and automake, but we use a moz.build file to build them, while still running their configure script (freetype and jemalloc). In all those cases, the sources are handled as if they had been Mozilla code all along.

But in the case of NSPR, NSS and ICU, we don’t necessarily build them in ways their respective build systems (were meant to) allow and rely on hacks around their build system to do our bidding. This is especially true for NSS (don’t look at config/external/nss/Makefile.in if you care about your sanity). On top of using atrocious hacks, that makes the build dependable on Make for compilation, in inefficient ways, at that.

In the future, we wouldn’t rely on NSPR, NSS and ICU build systems, and would build them as if they were Mozilla code, like the others. We need to find ways to allow that while limiting the cost of updates to new versions. This is especially true for ICU which is entirely third party. For NSPR and NSS, we have some kind of foothold. Although it is highly unlikely we can make them switch to moz.build (and in the current state of moz.build, being very tied to Gecko, not possible without possibly significant changes), we can probably come up with schemes that would allow to e.g. easily generate moz.build files from their Makefiles and/or manifests. I expect this to be somewhat manageable for NSS and NSPR. ICU is an entirely different story, sadly.

And more

There are many other aspects of the build system that I’m not mentioning here, but you’ll excuse me as this post is already long enough (and took much longer to write than it really should).

|

|