Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Mike Conley: DocShell in a Nutshell – Part 1: Original Intents |

I think in order to truly understand what the DocShell currently is, we have to find out where the idea of creating it came from. That means going way, way back to its inception, and figuring out what its original purpose was.

So I’ve gone back, peered through various archived wiki pages, newsgroup and mailing list posts, and I think I’ve figured out that original purpose.1

The original purpose can be, I believe, summed up in a single word: embedding.

Embedding

Back in the late 90's, sometime after the Mozilla codebase was open-sourced, it became clear to some folks that the web was “going places”. It was the “bees knees”. It was the “cat’s pajamas”. As such, it was likely that more and more desktop applications were going to need to be able to access and render web content.

The thing is, accessing and rendering web content is hard. Really hard. One does not simply write web browsing capabilities into their application from scratch hoping for the best. Heartbreak is in that direction.

Instead, the idea was that pre-existing web engines could be embedded into other applications. For example, Steam, Valve’s game distribution platform, displays a ton of web content in its user interface. All of those Steam store pages? Those are web pages! They’re using an embedded web engine in order to display that stuff.2

So making Gecko easily embeddable was, at the time, a real goal, and a real project.

nsWebShell

The problem was that embedding Gecko was painful. The top-level component that embedders needed to instantiate and communicate with was called “nsWebShell”, and it was a pretty unwieldy. Lots of internal knowledge about the internal workings of Gecko was leaked through the nsWebShell component, and it’s interface changed far too often.

It was also inefficient – the nsWebShell didn’t just represent the top-level “thing that loads web content”. Instances of nsWebShell were also used recursively for subdocuments within those documents – for example, (i)frames within a webpage. These nested nsWebShell’s formed a tree. That’s all well and good, except for the fact that there were things that the nsWebShell loaded or did that only the top-level nsWebShell really needed to load or do. So there was definitely room for some performance improvement.

In order to correct all of these issues, a plan was concocted to retire nsWebShell in favour of several new components and a slew of new interfaces. Two of those new components were nsDocShell and nsWebBrowser.

nsWebBrowser

nsWebBrowser would be the thing that embedders would drop into the applications – it would be the browser, and would do all of the loading / doing of things that only the top-level web browser needed to do.

The interface for nsWebBrowser would be minimal, just exposing enough so that an embedder could drop one into their application with little fuss, point it at a URL, set up some listeners, and watch it dance.

nsDocShell

nsDocShell would be… well, everything else that nsWebBrowser wasn’t. So that dumping ground that was nsWebShell would get dumped into nsDocShell instead. However, a number of new, logically separated interfaces would be created for nsDocShell.

Examples of those interfaces were:

- nsIDocShell

- nsIDocShellTreeItem

- nsIDocShellTreeNode

- nsIWebNavigation

- nsIWebProgress

- nsIBaseWindow

- nsIScrollable

- nsITextScroll

- nsIContentViewerContainer

- nsIInterfaceRequestor

- nsIScriptGlobalObjectOwner

- nsIRefreshURI

So instead of a gigantic, ever changing interface, you had lots of smaller interfaces, many of which could eventually be frozen over time (which is good for embedders).

These interfaces also made it possible to shield embedders from various internals of the nsDocShell component that embedders shouldn’t have to worry about.

Ok, but… what was it?

But I still haven’t answered the question – what was the DocShell at this point? What was it supposed to do now that it was created.

This ancient wiki page spells it out nicely:

This class is responsible for initiating the loading and viewing of a document.

This document also does a good job of describing what a DocShell is and does.

Basically, any time a document is to be viewed, a DocShell needs to be created to view it. We create the DocShell, and then we point that DocShell at the URL, and it does the job of kicking off communications via the network layer, and dealing with the content once it comes back.

So it’s no wonder that it was (and still is!) a dumping ground – when it comes to loading and displaying content, nsDocShell is the central nexus point of communications for all components that make that stuff happen.

I believe that was the original purpose of nsDocShell, anyhow.

And why “shell”?

This is a simple question that has been on my mind since I started this. What does the “shell” mean in nsDocShell?

Y’know, I think it’s actually a fragment left over from the embedding work, and that it really has no meaning anymore. Originally, nsWebShell was the separation point between an embedder and the Gecko web engine – so I think I can understand what “shell” means in that context – it’s the touch-point between the embedder, and the embedee.

I think nsDocShell was given the “shell” monicker because it did the job of taking over most of nsWebShell’s duties. However, since nsWebBrowser was now the touch-point between the embedder and embedee… maybe shell makes less sense. I wonder if we missed an opportunity to name nsDocShell something better.

In some ways, “shell” might make some sense because it is the separation between various documents (the root document, any sibling documents, and child documents)… but I think that’s a bit of a stretch.

But now I’m racking my brain for a better name (even though a rename is certainly not worth it at this point), and I can’t think of one.

What would you rename it, if you had the chance?

What is nsDocShell doing now?

I’m not sure what’s happened to nsDocShell over the years, and that’s the point of the next few posts in this series. I’m going to be going through the commits hitting nsDocShell from 1999 until the present day to see how nsDocShell has changed and evolved.

Hold on to your butts.

Further reading

The above was gleaned from the following sources:

- http://www-archive.mozilla.org/projects/blackwood/webclient/extra/03-02-00-travis.txt

- http://www-archive.mozilla.org/projects/embedding/webbrowser.html

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Gecko/Embedding_Mozilla/

- http://www-archive.mozilla.org/projects/webshell/

- http://www-archive.mozilla.org/projects/embedding/embedapiref/embedapiIX.html

- http://www-archive.mozilla.org/projects/embedding/embedshell/design.html

- http://www-archive.mozilla.org/projects/webshell/design.html

- http://www-archive.mozilla.org/projects/embedding/docshell.html

- http://www-archive.mozilla.org/newlayout/doc/webwidget.html

- http://mxr.mozilla.org/mozilla-central/source/docshell/base/nsIDocShell.idl

I’m very much prepared to be wrong about any / all of this. I’m making assertions and drawing conclusions by reading and interpreting things that other people have written about DocShell – and if the telephone game is any indication, this indirect analysis can be lossy. If I have misinterpreted, misunderstood, or completely missed the point in any of the above, please don’t hesitate to comment, and I will correct it forthwith.

http://mikeconley.ca/blog/2014/07/07/docshell-in-a-nutshell-part-1-original-intents/

|

|

Mark Surman: MoFo Update (and Board Slides) |

A big priority for Mozilla in 2014 is growing our community: getting more people engaged in everything from bringing the web to mobile and teaching web literacy to millions of people around the world. At our June Mozilla Foundation board meeting, I provided an update on the MoFo teams contribution to this effort during Q2 and on our plans for the next quarter. Here is a brief screen cast that summarizes the material fromt that meeting.

In addition to the screencast, I have posted the full board deck (40 slides) here. Much of the deck focuses on our progress towards the goal of 10k Webmaker contributors in 2014. If you want a quick overview of that piece of what we’re working on, here are some notes I wrote up to explain the Webmaker slides:

- Our overall annual goal: grow Webmaker community to include 10k active contributors teaching web literacy by end of 2014.

- The main focus of Q2 was to respin Webmaker as a platform for people who want to teach web literacy with Mozilla. Main things we achieved:

- Over 250 partners secured and 100s of events created in advance for 2014 Maker Party (Q2 goal: Pre-launch Maker Party 2014 for partners and contributors)

- A new version of Webmaker.org released in June oriented towards the needs of instructors who want to contribute to Mozilla (Q2 goal: re-launch webmaker.org with new UX)

- Related result: over 3000 people signed up to teach w/ Mozilla this summer as Party of Maker Party.

- Developed and released comprehensive web literacy curriculum — as well as new platform of Webmaker.org for people to publish and remix curriculum themselves (Q2 goal: Release web literacy ‘texbook’ at webmaker.org/explore)

- In addition, we spun up a new joint MoCo / MoFo program in Q2 called the Mobile Opportunity Initiative.

- This initiative will focus on local app and content creation in markets where FirefoxOS is launching, and will include development of easy app authoring tools as well as Webmaker training to go along with this. (Q2 goal: pilot Webmaker Mobile + local content program (includes FFos))

- For Q3: the main goals are to a) run a successful Maker Party and b) grow the number of people we have contributing to Mozilla by teaching web literacy. Specific goal: Maker Party reach and impact builds on 2013.KPIs: 2400 events + 6500 contributors

- We also want to use Q3 to grow Maker Party from a yearly campaign into a year round program — or network of ‘clubs’ — for people teaching with Mozilla.New features added to support year round ‘teach the web’ program. Specific goal: Add new features added to support year round ‘teach the web’ program

- Finally, Q3 will include a getting meat on the bones for the Mobile Opportunity Initiative, including prototypes of what Appmaker could offer to users. Specific goal: Announce digital inclusion initiative w/ partners from mobile industry. KPIs: 3 carrier partners and 3 philanthropic partners aligned *and* three ‘appmaker’ user value concepts tested in field w/ at least 300 content creators

The slides also talk about our joint efforts with MoCo to grow the number of Mozilla contributors overall to 20,000 people in 2014. In addition to Webmaker, Mozilla’s Open News, Science Lab, Open Internet Policy and MozFest initiatives are all a part of growing our contributor community. There is also a financial summary. We are currently $12M towards our $17M revenue goal for the year.

For back ground and context, see Mozilla’s overall 2014 goals here and the quarterly goal tracker here. If you have questions or comments on any of this, please reach out to me directly or leave comments below.

Filed under: mozilla, statusupdate, webmakers

http://commonspace.wordpress.com/2014/07/07/mofo-update-and-board-slides/

|

|

William Lachance: Measuring frames per second and animation smoothness with Eideticker |

[ For more information on the Eideticker software I'm referring to, see this entry ]

Just wanted to write up a few notes on using Eideticker to measure animation smoothness, since this is a topic that comes up pretty often and I wind up explaining these things repeatedly. ![]()

When rendering web content, we want the screen to update something like 60 times per second (typical refresh rate of an LCD screen) when an animation or other change is occurring. When this isn’t happening, there is often a user perception of jank (a.k.a. things not working as they should). Generally we express how well we measure up to this ideal by counting the number of “frames per second” that we’re producing. If you’re reading this, you’re probably already familiar with the concept in outline. If you want to know more, you can check out the wikipedia article which goes into more detail.

At an internal level, this concept matches up conceptually with what Gecko is doing. The graphics pipeline produces frames inside graphics memory, which is then sent to the LCD display (whether it be connected to a laptop or a mobile phone) to be viewed. By instrumenting the code, we can see how often this is happening, and whether it is occurring at the right frequency to reach 60 fps. My understanding is that we have at least some code which does exactly this, though I’m not 100% up to date on how accurate it is.

But even assuming the best internal system monitoring, Eideticker might still be useful because:

- It is more “objective”. This is valuable not only for our internal purposes to validate other automation (sometimes internal instrumentation can be off due to a bug or whatever), but also to “prove” to partners that our software has the performance characteristics that we claim.

- The visual artifacts it leaves behind can be valuable for inspection and debugging. i.e. you can correlate videos with profiling information.

Unfortunately, deriving this sort of information from a video capture is more complicated than you’d expect.

What does frames per second even mean?

Given a set of N frames captured from the device, the immediate solution when it comes to “frames per second” is to just compare frames against each other (e.g. by comparing the value of individual pixels) and then counting the ones that are different as “unique frames”. Divide the total number of unique frames by the length of the

capture and… voila? Frames per second? Not quite.

First off, there’s the inherent problem that sometimes the expected behaviour of a test is for the screen to be unchanging for a period of time. For example, at the very beginning of a capture (when we are waiting for the input event to be acknowledged) and at the end (when we are waiting for things to settle). Second, it’s also easy to imagine the display remaining static for a period of time in the middle of a capture (say in between gestures in a multi-part capture). In these cases, there will likely be no observable change on the screen and thus the number of frames counted will be artificially low, skewing the frames per second number down.

Measurement problems

Ok, so you might not consider that class of problem that big a deal. Maybe we could just not consider the frames at the beginning or end of the capture. And for pauses in the middle… as long as we get an absolute number at the end, we’re fine right? That’s at least enough to let us know that we’re getting better or worse, assuming

that whatever we’re testing is behaving the same way between runs and we’re just trying to measure how many frames hit the screen.

I might agree with you there, but there’s a further problems that are specific to measuring on-screen performance using a high-speed camera as we are currently with FirefoxOS.

An LCD updates gradually, and not all at once. Remnants of previous frames will remain on screen long past their interval. Take for example these five frames (sampled at 120fps) from a capture of a pan down in the FirefoxOS Contacts application (movie):

Note how if you look closely these 5 frames are actually the intersection of *three* seperate frames. One with “Adam Card” at the top, another with “Barbara Bloomquist” at the top, then another with “Barbara Bloomquist” even further up. Between each frame, artifacts of the previous one are clearly visible.

Plausible sounding solutions:

- Try to resolve the original images by distinguishing “new” content from ghosting artifacts. Sounds possible, but probably hard? I’ve tried a number of simplistic techniques (i.e. trying to find times when change is “peaking”), but nothing has really worked out very well.

- Somehow reverse engineering the interface between the graphics chipset and the LCD panel, and writing some kind of custom hardware to “capture” the framebuffer as it is being sent from one to the other. Also sounds difficult.

- Just forget about this problem altogether and only try to capture periods of time in the capture where the image has stayed static for a sustained period of time (i.e. for say 4-5 frames and up) and we’re pretty sure it’s jank.

Personally the last solution appeals to me the most, although it has the obvious disadvantage of being a “homebrew” metric that no one has ever heard of before, which might make it difficult to use to prove

that performance is adequate — the numbers come with a long-winded explanation instead of being something that people immediately understand.

|

|

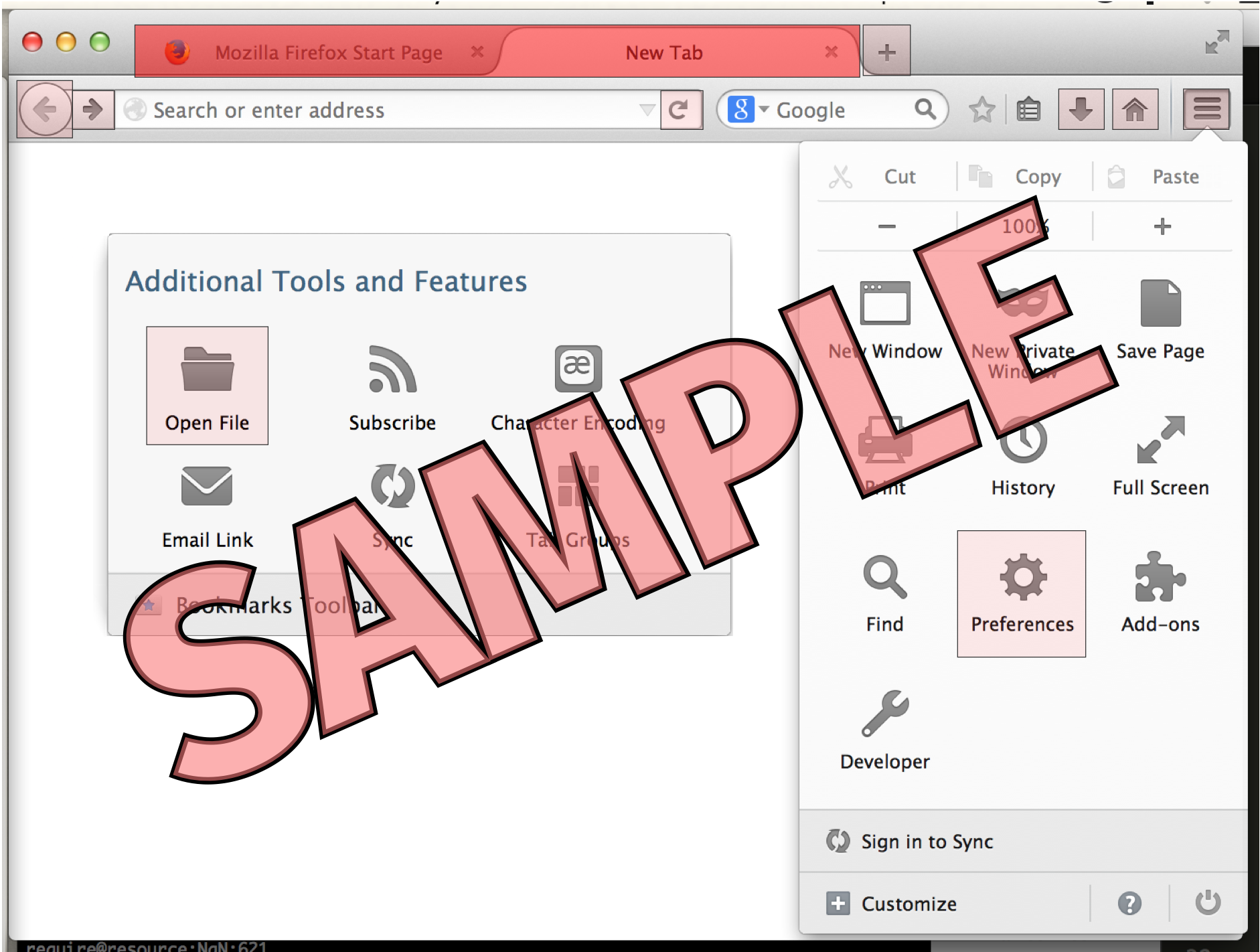

Blake Winton: Figuring out where things are in an image. |

People love heatmaps.

They’re a great way to show how much various UI elements are used in relation to each other, and are much easier to read at a glance than a table of click- counts would be. They can also reveal hidden patterns of usage based on the locations of elements, let us know if we’re focusing our efforts on the correct elements, and tell us how effective our communication about new features is. Because they’re so useful, one of the things I am doing in my new role is setting up the framework to provide our UX team with automatically updating heatmaps for both Desktop and Android Firefox.

Unfortunately, we can’t just wave our wands and have a heatmap magically appear. Creating them takes work, and one of the most tedious processes is figuring out where each element starts and stops. Even worse, we need to repeat the process for each platform we’re planning on displaying. This is one of the primary reasons we haven’t run a heatmap study since 2012.

In order to not spend all my time generating the heatmaps, I had to reduce the effort involved in producing these visualizations.

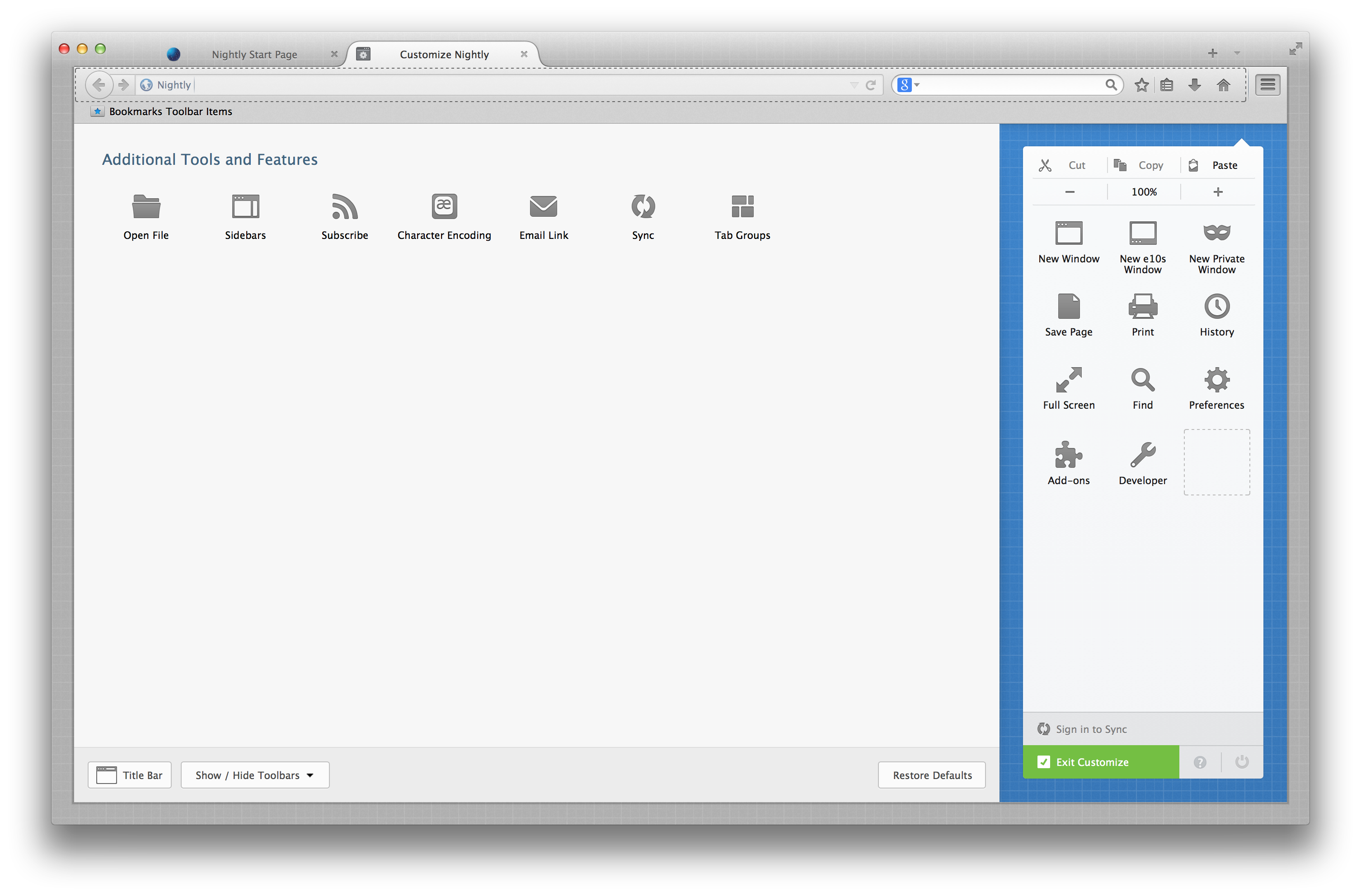

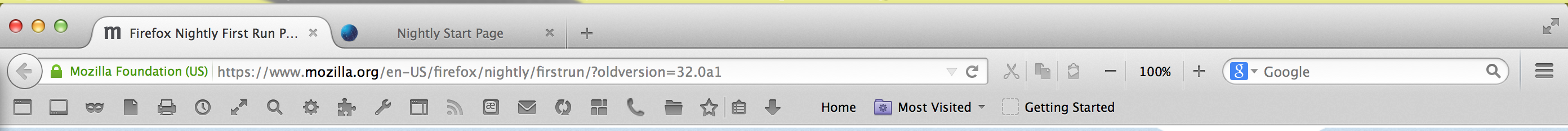

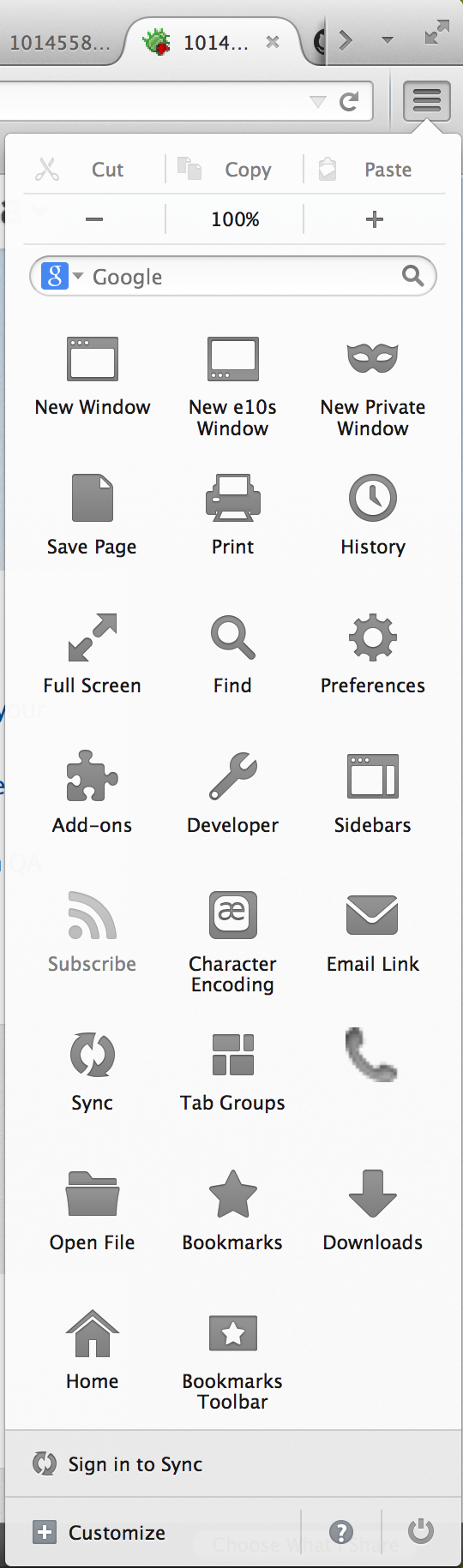

Being a programmer, my first inclination was to write a program to calculate them, and that sort of worked for the first version of the heatmap, but there were some difficulties. To collect locations for all the elements, we had to display all the elements.

Customize mode (as shown above) was an obvious choice since it shows everything you could click on almost by definition, but it led people to think that we weren’t showing which elements were being clicked the most, but instead which elements people customized the most. So that was out.

Next we tried putting everything in the toolbar, or the menu, but those were a little too cluttered even without leaving room for labels, and too wide (or too tall, in the case of the menu).

Similarly, I couldn’t fit everything into the menu panel either. The only solution was to resort to some Photoshop-trickery to fit all the buttons in, but that ended up breaking the script I was using to locate the various elements in the UI.

Since I couldn’t automatically figure out where everything was, I figured we might as well use a nicely-laid out, partially generated image, and calculate the positions (mostly-)manually.

I had foreseen the need for different positions for the widgets when the project started, and so I put the widget locations in their own file from the start. This meant that I could update them without changing the code, which made it a little nicer to see what’s changed between versions, but still required me to reload the whole page every time I changed a position or size, which would just have taken way too long. I needed something that could give me much more immediate feedback.

Fortunately, I had recently finished watching a series of videos from Ian Johnson (@enjalot on twitter) where he used a tool he made called Tributary to do some rapid prototyping of data visualization code. It seemed like a good fit for the quick moving around of elements I was trying to do, and so I copied a bunch of the code and data in, and got to work moving things around.

I did encounter a few problems: Tributary wasn’t functional in Firefox Nightly (but I could use Chrome as a workaround) and occasionally sometimes trying to move the cursor would change the value slider instead. Even with these glitches it only took me an hour or two to get from set-up to having all the numbers for the final result! And the best part is that since it's all open source, you can take a look at the final result, or fork it yourself!

http://weblog.latte.ca/blake/employment/mozilla/firefox/Heatmap1.html

|

|

Christian Heilmann: Yahoo login issue on mobile – don’t fix the line length of your emails |

Yesterday I got a link to an image on Flickr in a tweet. Splendid. I love Flickr. It has played a massive role in the mashup web, I love the people who work in there and it used to be a superb place to store and share photos without pestering people to sign up for something. Twitter has also been a best-of-breed when it comes to “hackable” URLs. I could get different sizes of images and different parts of people’s pages simply by modifying the URL in a meaningful way. All in all, a kick-ass product, I loved, adored, contributed to and gave to people as a present.

Until I started using a mobile device.

Well, I tapped on the link and got redirected to Chrome on my Nexus 5. Instead of seeing an image as I expected I got a message that I should please download the epic Flickr app. No thanks, I just want to see this picture, thank you very much. I refused to download the app and went to the “web version” instead.

This one redirected me to the Yahoo login. I entered my user name and password and was asked “for security reasons” to enter animated captcha. I am not kidding, here it is:

I entered this and was asked to verify once more that I am totally me and would love to see this picture that was actually not private or anything so it would warrant logging in to start with.

I got the option to do an email verification or answer one of my security questions. Fine, let’s do the email verification.

An email arrived and it looked like this:

As you can see (and if not, I am telling you now) the text seems cut off and there is no code in the email. Touching the text of the mail allows me to scroll to the right and see the full stop after “account.” I thought at first the code was embedded as an image and google had filtered it out, but there was no message of that sort.

Well, that didn’t help. So I went back in the verification process and answered one of my questions instead. The photo wasn’t worth it.

What happened?

By mere chance I found the solution. You can double-tap the email in GMail for Android and it extends it to the full text. Then you can scroll around. For some reason the longest line gets displayed and the rest collapsed.

The learning from that: do not fix line widths in emails (in this case it seems 550px as a layout table) if you display important information.

I am not sure if that is a bug or annoyance in GMail, but in any case, this is not a good user experience. I reported this to Yahoo and hopefully they’ll fix this in the login verification mail.

|

|

Bogomil Shopov: Why webcompat.com should do better + a proposal |

I really like the webcompat project‘s idea: to allow all users to be able to report bugs on all websites and in all browsers. Let’s take a step back: What are the 3 main problems with bug-reporting in general?

Most of the users are not-so-tech savvy.

It’s true. They know something is wrong, because the website is not working for them, but they don’t know why is that or how to report it. Imagine if they could use the tools they are familiar with to report bugs and to give the developers the data they need without even realizing it. Cool huh?

“It’s working for me”

Thanks to different browsers, standards and different developers a website that one user sees can be completely different for another user. Agreed?

You can imagine the questions the user must answer:: “On which page are you?”, “What are you doing exactly?”, “Did you select something wrong?”, “Did you write a number in your street address as requested?”, “Are you logged in?”, etc.

It’s an option too: the developer (or a QA) will say to the user “It’s working for me”, meaning to the end user - you are doing something wrong, John or Jane, it’s not the website. it’s you.

The end user doesn’t know how to fill-in bugs into bug tracking systems

Majority of the people that can find a bug don’t know how to report it or why to report it. Most of the companies or projects have 1-2 page howto’s attached to the bug reporting form, but the result is still questionable.

The WebCompat way: Now

Webcompat will give all users a brand new way to report bugs. It will also provide for a community which will be able to easily find fixes for the bugs or alternatively, contact the website owners and report them.

There is still one problem with that. The users are still missing the tools which they are familiar with to report bugs. The developers (community of fixers) are still missing the vital information about fixing the bug.

The WebCompat way: Upgraded

We can fix that! Being part of Usersnap’s mission to make this process easier, I can propose a solution and being a Mozillian for almost a decade I believe this will help millions of users to report bugs and to make the web a better place – this is why Usersnap has been created for.

The ideal set of information to fix a bug from the developer’s perspective:

- Obviously, a report of what exactly is not working

- Information about the plug-ins installed in the browser

- OS and browser version, at a minimum

- JavaScript error log and the XMLHttpRequest Log in case there are problems (we still don’t know that). The worst thing about client-side JavaScript errors is that they happen on the client side, which is a cruel place far away from the developer trying to fix this error.

- It would also be great to know what the user did BEFORE the error (yes we can do that)

Wouldn’t it be awesome if we could have this information to every bug report, collected automatically.

Push to gitHub

And what is the best part of this? All data goes directly to your bug tracking solutions – in this case gitHub and everybody is happy.

http://talkweb.eu/why-webcompat-com-should-do-better-a-proposal/

|

|

Mozilla WebDev Community: Webdev Extravaganza July 2014 Notes |

Once a month, web developers across the Mozilla Project get together to talk about the things we’ve shipped, discuss the libraries we’re working on, introduce any new faces, and argue about pointless things. We call it the Webdev Extravaganza! It’s open to the public; you should come next month!

There’s a wiki page that’s mostly useful for pre-meeting connection info and agenda-building, a recording of the meeting, and an etherpad which is a mix of semi-useful info and avant-garde commentary. This month, I’m trying out writing a post-meeting blog post that serves as a more serious log of what was shared during the meeting.

Shipping Celebration

The shipping celebration is for sharing anything that we have shipped in the past month, from incremental updates to our sites to brand new sites to library updates.

Mobile Partners

mobilepartners.mozilla.org is a Mezzanine-based site that allows phone manufacturers and operators to learn about Firefox OS and sign up as a partner. This month we shipped an update that, among other things, tightens up the site’s Salesforce integration, replaces HTML-based agreements with PDF-based ones displayed via PDF.js, and moves the site off of old Mozilla Labs hardware.

Input

input.mozilla.org got two major features shipped:

- All non-English feedback for Firefox OS is now being automatically sent to humans for translation. Having the feedback translated allows processes that work on English only, like Input’s sentiment analysis, to run on feedback from non-English users.

- An improved GET API for pulling data from Input, useful primarily for creating interesting dashboards without having to build them into Input itself.

Open Source Citizenship

Peep has an IRC channel

Peep is a wrapper around pip that vets packages downloaded from PyPI via a hash in your requirements file. There’s now an IRC channel for discussing peep development: #peep on irc.mozilla.org.

Spiderflunky

Spiderflunky is a static analysis tool for JavaScript that was modified from a tool for inspecting packaged apps called perfalator. DXR is planning to use it, and there’s interest around the project, so it has it’s own repository now.

New Hires / Interns / Volunteers

This month we have several new interns (including a bunch from the Open Source Lab at OSU):

| Name | IRC Nick | Project |

|---|---|---|

| Trevor Bramwell | bramwelt | crash-stats.mozilla.com |

| Ian Kronquist | muricula | input.mozilla.org |

| Dean Johnson | deanj | support.mozilla.org |

| Marcell VazquezChanlatte | marcell | dxr.mozilla.org |

| Christian Weiss | cweiss | Web Components / Brick |

Bikeshed / Roundtable

In the interests of time and comprehensibility, open discussions will be ignored.

What does Webdev do?

As part of an ongoing effort to improve webdev, there’s an etherpad for listing the things that webdev does, along with who owns them, what goals they contribute to, and how they can be improved. You are encouraged to take a look and add info or opinions by the end of the week.

Interesting Python Stuff

Erik Rose shared a backport of concurrent.futures from Python 3.2 and a feature from setuptools called entry points that is useful for, among other things, supporting a plugin architecture in your library.

Did you find this post useful? Let us know and we might do it again next month!

Until then, STAY INCLUSIVE, KIDS

https://blog.mozilla.org/webdev/2014/07/06/webdev-extravaganza-july-2014-notes/

|

|

Nicholas Nethercote: Measuring memory used by third-party code |

Firefox’s memory reporting infrastructure, which underlies about:memory, is great. And when it lacks coverage — causing the “heap-unclassified” number to get large — we can use DMD to identify where the unreported allocations are coming from. Using this information, we can extend existing memory reporters or write new ones to cover the missing heap blocks.

But there is one exception: third-party code. Well… some libraries support custom allocators, which is great, because it lets us provide a counting allocator. And if we have a copy of the third-party code within Firefox, we can even use some pre-processor hacks to forcibly provide custom counting allocators for code that doesn’t support them.

But some heap allocations are done by code we have no control over, like OpenGL drivers. For example, after opening a simple WebGL demo on my Linux box, I have over 50% “heap-unclassified”.

208.11 MB (100.0%) -- explicit +--107.76 MB (51.78%) -- heap-unclassified

DMD’s output makes it clear that the OpenGL drivers are responsible. The following record is indicative.

Unreported: 1 block in stack trace record 2 of 3,597 15,486,976 bytes (15,482,896 requested / 4,080 slop) 6.92% of the heap (20.75% cumulative); 10.56% of unreported (31.67% cumulative) Allocated at replace_malloc (/home/njn/moz/mi8/co64dmd/memory/replace/dmd/../../../../memory/replace/dmd/DMD.cpp:1245) 0x7bf895f1 _swrast_CreateContext (??:?) 0x3c907f03 ??? (/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/dri/i965_dri.so) 0x3cd84fa8 ??? (/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/dri/i965_dri.so) 0x3cd9fa2c ??? (/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/dri/i965_dri.so) 0x3cd8b996 ??? (/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/dri/i965_dri.so) 0x3ce1f790 ??? (/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/dri/i965_dri.so) 0x3ce1f935 glXGetDriverConfig (??:?) 0x3dce1827 glXDestroyGLXPixmap (??:?) 0x3dcbc213 glXCreateNewContext (??:?) 0x3dcbc48a mozilla::gl::GLContextGLX::CreateGLContext(mozilla::gfx::SurfaceCaps const&, mozilla::gl::GLContextGLX*, bool, _XDisplay*, unsigned long, __GLXFBConfigRec*, bool, gfxXlibSurface*) (/home/njn/moz/mi8/co64dmd/gfx/gl/../../../gfx/gl/GLContextProviderGLX.cpp:783) 0x753c99f4

The bottom-most frame is for a function (CreateGLContext) within Firefox’s codebase, and then control passes to the OpenGL driver, which eventually does a heap allocation, which ends up in DMD’s replace_malloc function.

The following DMD report is a similar case that shows up on Firefox OS.

Unreported: 1 block in stack trace record 1 of 463 1,454,080 bytes (1,454,080 requested / 0 slop) 9.75% of the heap (9.75% cumulative); 21.20% of unreported (21.20% cumulative) Allocated at replace_calloc /Volumes/firefoxos/B2G/gecko/memory/replace/dmd/DMD.cpp:1264 (0xb6f90744 libdmd.so+0x5744) os_calloc (0xb25aba16 libgsl.so+0xda16) (no addr2line) rb_alloc_primitive_lists (0xb1646ebc libGLESv2_adreno.so+0x74ebc) (no addr2line) rb_context_create (0xb16446c6 libGLESv2_adreno.so+0x726c6) (no addr2line) gl2_context_create (0xb16216f6 libGLESv2_adreno.so+0x4f6f6) (no addr2line) eglCreateClientApiContext (0xb25d3048 libEGL_adreno.so+0x1a048) (no addr2line) qeglDrvAPI_eglCreateContext (0xb25c931c libEGL_adreno.so+0x1031c) (no addr2line) eglCreateContext (0xb25bfb58 libEGL_adreno.so+0x6b58) (no addr2line) eglCreateContext /Volumes/firefoxos/B2G/frameworks/native/opengl/libs/EGL/eglApi.cpp:527 (0xb423dda2 libEGL.so+0xeda2) mozilla::gl::GLLibraryEGL::fCreateContext(void*, void*, void*, int const*) /Volumes/firefoxos/B2G/gecko/gfx/gl/GLLibraryEGL.h:180 (discriminator 3) (0xb4e88f4c libxul.so+0x789f4c)

We can’t traverse these allocations in the usual manner to measure them, because we have no idea about the layout of the relevant data structures. And we can’t provide a custom counting allocator to code outside of Firefox’s codebase.

However, although we pass control to the driver, control eventually comes back to the heap allocator, and that is something that we do have some power to change. So I had an idea to toggle some kind of mode that records all the allocations that occur within a section of code, as the following code snippet demonstrates.

SetHeapBlockTagForThread("webgl-create-new-context");

context = glx.xCreateNewContext(display, cfg, LOCAL_GLX_RGBA_TYPE, glxContext, True);

ClearHeapBlockTagForThread();

The calls on either side of glx.xCreateNewContext tell the allocator that it should tag all allocations done within that call. And later on, the relevant memory reporter can ask the allocator how many of these allocations remain and how big they are. I’ve implemented a draft version of this, and it basically works, as the following about:memory output shows.

216.97 MB (100.0%) -- explicit +---78.50 MB (36.18%) -- webgl-contexts +---32.37 MB (14.92%) -- heap-unclassified

The implementation is fairly simple.

- There’s a global hash table which records which live heap blocks have a tag associated with them. (Most heap blocks don’t have a tag, so this table stays small.)

- When

SetHeapBlockTagForThreadis called, the given tag is stored in thread-local storage. WhenClearHeapBlockTagForThreadis called, the tag is cleared. - When an allocation happens, we (quickly) check if there’s a tag set for the current thread and if so, put a (pointer,tag) pair into the table. Otherwise, we do nothing extra.

- When a deallocation happens, we check if the deallocated block is in the table, and remove it if so.

- To find all the live heap blocks with a particular tag, we simply iterate over the table looking for tag matches. This can be used by a memory reporter.

Unfortunately, the implementation isn’t suitable for landing in Firefox’s code, for several reasons.

- It uses Mike Hommey’s

replace_mallocinfrastructure to wrap the default allocator (jemalloc). This works well — DMD does the same thing — but using it requires doing a special build and then setting some environment variables at start-up. This is ok for an occasional-use tool that’s only used by Firefox developers, but it’s important that about:memory works in vanilla builds without any additional effort. - Alternatively, I could modify jemalloc directly, but we’re hoping to one day move away from our old, heavily-modified version of jemalloc and start using an unmodified jemalloc3.

- It may have a non-trivial performance hit. Although I haven’t measured performance yet — the above points are a bigger show-stopper at the moment — I’m worried about having to do a hash table lookup on every deallocation. Alternative implementations (store a marker in each block, or store tagged blocks in their own zone) are possible but present their own difficulties.

- It can miss some allocations. When adding a tag for a particular section of code, you don’t want to mark every allocation that occurs while that section executes, because there could be multiple threads running and you don’t want to mark allocations from other threads. So it restricts the marking to a single thread, but if the section creates a new thread itself, any allocations done on that new thread will be missed. This might sound unlikely, but my implementation appears to miss some allocations and this is my best theory as to why.

This issue of OpenGL drivers and other kinds of third-party code has been a long-term shortcoming with about:memory. For the first time I have a partial solution, though it still has major problems. I’d love to hear if anyone has additional ideas on how to make it better.

https://blog.mozilla.org/nnethercote/2014/07/07/measuring-memory-used-by-third-party-code/

|

|

Patrick Cloke: New Blog: Serving the Content |

In the first part of this blog post I talked about using Pelican to create a blog, this is a bit more about how I got it up and running.

Getting a Domain

The most exciting part! Getting a domain! I used gandi.net, it was recommended to me by Florian as "awesome, but a bit expensive". I liked that they actually explain exactly what I was getting by registering a domain through them. Nowhere else I looked was this explicit.

Once you get your domain you’ll need to set up your CNAME record to forward to wherever you’re serving your content. I found it pretty interesting that gandi essentially gives you an DNS zone file to modify. I ended up making a few modifications:

- Created a patrick subdomain (patrick.cloke.us)

- Redirected the apex domain (cloke.us) to the patrick subdomain

- Redirected the www subdomain to the patrick subdomain

I also created a few email aliases which forward to the email accounts I already own.

Serving the Content

OK, we have a domain! We have content! How do we actually link them!? I used GitHub Pages, cause I’m cheap and don’t like to pay for things. The quick version:

- Create a repository that is named

name>.github.io - Push whatever HTML content you want into the master branch

- Voila it’s available as

.github.io

Personally, I store my Pelican code in a separate source branch [1] and use ghp-import to actually publish my content. I’ve automated a lot of the tasks by extending the default fabfile.py that is generated with the quickstart. My workflow looks something like:

komodo content/new-article.rst ## serve/regenerate> git add content/ && git commit -m "Add 'New Article!'." fab publish # Which runs "ghp-import -p -b master output" underneath! git push origin source

One other thing you’ll need to do is add a CNAME file that has the domain of your host in it (and only the domain). I found the GitHub documents on this extremely confusing, but it’s pretty simple:

- Create a file called CNAME somewhere you have static files in Pelican (mine is at content/static/CNAME)

- Add a line to your pelicanconf.py to have this file end up in the root:

# Set up static content and output locations. STATIC_PATHS = [ 'images', 'static/CNAME' ] EXTRA_PATH_METADATA = { 'static/CNAME': {'path': 'CNAME'}, }

It took 10 - 20 minutes for this to "kick in" on GitHub, until that time I had a 404 GitHub page.

Redirect Blogger

This is the really fun part. How the hell do we redirect blogger links to actually go to the new location of each blog post? With some hackery, some luck, and some magic.

I found some help in an article about switching to WordPress from Blogger and modified the template they had there. On the Blogger dashboard, choose "Template", scroll to the bottom and click "Revert to Classic Template". Then use something like the following template:

span> href="http://patrick.cloke.us"><$BlogTitle$>

Obviously you’ll need to change the URLs, but the key parts here are that we’re generating a URL based on the date and the full article name. The magic comes in generating the date. The get it in the format I wanted (YYYY/MM/DD) I modified a the "Date Header Format" in "Settings" > "Language and formatting". This matches how I formatted my URLs in my pelicanconf.py. The slug that gets generated needs to match the slug you used in your template so the link will work. (I had some help in figuring out these template tags.)

I’d suggest you check the links to all your articles! A couple of the dates were messed up in mine (the day was off by one, causing the forwarded location to be broken).

The last thing to do is to redirect the Atom/RSS feed (if anyone is using that). Go to "Settings" > "Other" > "Post Feed Redirect URL" and set it to your new Atom feed URL (wherever that might be).

| [1] | Pro-tip: You can change the "default" branch of your repository in the settings page on GitHub. |

http://patrick.cloke.us/posts/2014/07/06/new-blog-serving-the-content/

|

|

Andrew Truong: Why do I even bother? |

Most of you know that I'm a SUMO (support.mozilla.org) contributor. I know that Mozilla is all about being open and certainly open to feedback. However, why should I still bother? It seems that the past few times, I've started a thread in the contributors forum and got a basic response. The suggestions, the feedback provided, seemed to be received but I don't think it's gone anywhere. No actions were made or taken after me suggesting items, all I received was a response that obviously doesn't satisfy or rectify the present issue. It seems to occur often that when something breaks, the "suggestion" from X period of time ago is fixed. Why not, take the feedback into account, see what can be done and then possibly work on it, instead of having X break which then a fix needs to be pushed out which resolves it.

I know by now, that teams are pressured, that there are set goals for each quarter and that they need to reach that goal. There doesn't seem to be any time for volunteers anymore, it's all about Mozilla. Why is is so hard nowadays to get something done?

Sure, I'm young, my feedback doesn't matter, and that's alright ![]()

I'm happy that there have been occasions where I do get awesome responses, but why do I still bother when the response I'm wanting is lacked?

I'll show some examples below:

https://support.mozilla.org/en-US/forums/social-media/710219

https://support.mozilla.org/en-US/forums/contributors/710304

https://support.mozilla.org/en-US/forums/contributors/710305

https://support.mozilla.org/en-US/forums/contributors/709519

The level of care seems to be gone. I know that Mozilla has its priorities, but what can a single person like me do?

|

|

Alex Clark: Pillow 2-5-0 is out! |

Pillow is the "friendly" PIL fork by Alex Clark and Contributors. PIL is the Python Imaging Library by Fredrik Lundh and Contributors

Since Pillow 2.0 the Pillow Team has adopted a quarterly release cycle; as such, Pillow 2.5.0 is out! Here's what's new in this release:

2.5.0 (2014-07-01)

- Imagedraw rewrite [terseus, wiredfool]

- Add support for multithreaded test execution [wiredfool]

- Prevent shell injection #748 [mbrown1413, wiredfool]

- Support for Resolution in BMP files #734 [gcq]

- Fix error in setup.py for Python 3 [matthew-brett]

- Pyroma fix and add Python 3.4 to setup metadata #742 [wirefool]

- Top level flake8 fixes #741 [aclark]

- Remove obsolete Animated Raster Graphics (ARG) support [hugovk]

- Fix test_imagedraw failures #727 [cgohlke]

- Fix AttributeError: class Image has no attribute 'DEBUG' #726 [cgohlke]

- Fix msvc warning: 'inline' : macro redefinition #725 [cgohlke]

- Cleanup #654 [dvska, hugovk, wiredfool]

- 16-bit monochrome support for JPEG2000 [videan42]

- Fixed ImagePalette.save [brightpisces]

- Support JPEG qtables [csinchok]

- Add binary morphology addon [dov, wiredfool]

- Decompression bomb protection [hugovk]

- Put images in a single directory [hugovk]

- Support OpenJpeg 2.1 [al45tair]

- Remove unistd.h #include for all platforms [wiredfool]

- Use unittest for tests [hugovk]

- ImageCms fixes [hugovk]

- Added more ImageDraw tests [hugovk]

- Added tests for Spider files [hugovk]

- Use libtiff to write any compressed tiff files [wiredfool]

- Support for pickling Image objects [hugovk]

- Fixed resolution handling for EPS thumbnails [eliempje]

- Fixed rendering of some binary EPS files (Issue #302) [eliempje]

- Rename variables not to use built-in function names [hugovk]

- Ignore junk JPEG markers [hugovk]

- Change default interpolation for Image.thumbnail to Image.ANTIALIAS [hugovk]

- Add tests and fixes for saving PDFs [hugovk]

- Remove transparency resource after P->RGBA conversion [hugovk]

- Clean up preprocessor cruft for Windows [CounterPillow]

- Adjust Homebrew freetype detection logic [jacknagel]

- Added Image.close, context manager support. [wiredfool]

- Added support for 16 bit PGM files. [wiredfool]

- Updated OleFileIO to version 0.30 from upstream [hugovk]

- Added support for additional TIFF floating point format [Hijackal]

- Have the tempfile use a suffix with a dot [wiredfool]

- Fix variable name used for transparency manipulations [nijel]

Acknowledgements

With every release, there are notable contributions I must acknowledge:

- Thanks to Stephen Johnson for contributing http://pillow.readthedocs.org, we continue to rely on & extend this resource.

- Thanks to Christopher Gohlke for producing Windows Egg, Exe, and Wheel distributions.

- Thanks to Matthew Brett for producing OS X Wheels (for the first time ever!)

- Thanks to Eric Soroos for his contributions and serving as "Pillow Man #2" (2nd in command).

- Welcome to Hugo VK who has joined the Pillow Team & contributed significantly to this release.

- Thanks to all the remaining unnamed contributors! We appreciate every commit.

Enjoy Pillow 2.5.0 & please report issues here: https://github.com/python-imaging/Pillow/issues

|

|

Kim Moir: This week in Mozilla Releng - July 4, 2014 |

Major highlights:

- Armen, although he works on Ateam now, made blobber uploads discoverable and blogged about it. Blobber is a server and client side set of tools that allow Releng's test infrastructure to upload files without requiring to deploy ssh keys on them.

- Callek and Coop, who served on buildduty during the past two weeks worked to address capacity issues with our test and build infrastructure. We hit a record of 88,000 jobs yesterday which led to high pending counts.

- Kim is trying to address the backlog of Android 2.3 test jobs by moving more test jobs to AWS from our inhouse hardware now that Geoff on the Ateam has found a suitable image.

- Rail switched jacuzzi EBS from magnetic to SSD. Jacuzzis are similar pools of build machines and switching their EBS storage from magnetic to SSD in AWS will improve build times.

- Buildduty

- Stale slaverebooter lockfile

- please upload a new tp5n.zip to get a network access fix

- Please upload blessings to internal PyPI

- Please deploy newer version of blobuploader

- upload a new mobile_tp4.zip pageset to the 3 headed remote talos server

- Problem with cannot create debug link section

- B2G hamachi_eng_nightly failing with "Giving up on gecko git revision for 31de1a84b27f."

- increase disk size for AWS buildbot masters

- Please deploy newer version of blobuploader (1.2.1)

- b-2008-sm-0009 is unreachable

- Something wrong with b-2008-ix-002x slaves

- upload a talos pages to the 3 headed remote talos server to revision f9136c4bc616

- B2G bumper bot hasn't made any commits for 6+ hours

- Windows 8 test jobs pending on Try for coming up to 3 hours

- General Automation

- Need automatic hsts preload list updates on any branches based on Gecko 18 and later

- Make blobber uploads discoverable

- Provision enough in-house master capacity

- Disable mochitest-metro on Cedar

- Allow in-tree json for Gaia-Try to specify which Gecko build to use.

- Please do not use http://puppetagain.pub.build.mozilla.org for high-reliability Python installs

- [tracker] run Android 2.3 test jobs on EC2

- Perma-fail on Linux64 slaves - test_hosted.xul,test_packaged.xul,test_packaged_launch.xul | Error during test: [Exception... "Component returned failure code: 0x80520012 (NS_ERROR_FILE_NOT_FOUND) [nsIFileOutputStream.init]" nsresult: "0x80520012

- generate "flatfish" builds for B2G

- Add the build step or else process name to buildbot's generic command timed out failure strings

- [Dolphin] Create Dolphin builds for 1.4

- [Dolphin] Need a way to build Dolphin builds for 1.4

- Require more free space for android builds

- switch tst* EBS from magnetic to SSD

- Tooltool doesn't work on (at least) windows c-c

- Increase Android 2.3 mochitest chunks, for aws

- Monitor aws_stop_idle.py hungs

- Hazard failures with rsync: connection unexpectedly closed (0 bytes received so far) [sender]

- Add more tst-linux64 slaves

- Update Gu job to build Gaia with DESKTOP_SHIMS=0

- Please clobber bld-linux64-spot-015

- Configure elm for linux builds

- Use tooltool for l10n builds

- Please deploy newer version of blobber

- Race condition between builders that push updates to in-tree files

- Unschedule Goop everywhere but cedar

- Add hazards builds to ash branch

- Start doing mulet builds on Fig

- Terminate buildbot-master65 instance

- Decommission the ionmonkey tree

- switch jacuzzi EBS from magnetic to SSD

- create in-tree CA pinning preload list

- Loan Requests

- loan linux64 ec2 slave to jmaher

- Requesting a loaner machine b2g_ubuntu64_vm to diagnose bug 1017490

- loan gbrown a c3.xlarge to test reftests etc again in AWS

- Request Loan Machine for tst-linux64-spot

- Other

- Allow developers to access Android emulator AVDs

- Provide a Mozilla API key for desktop builds

- sign Thunderbird hot-fix testing addon

- No Firefox win32 l10n builds for mozilla-central since June 25th

- Platform Support

- Upload new version of xulrunner to tooltool

- Redirect runner logging output to /var/log/runner.log

- rc3.d/ symlinks should refresh on initscript updates for runner and buildbot

- Segmentation fault on gaia try server with pull request from bug 1017490

- Update version of pip installed on automation machines from 0.8.2 to 1.5.5

- address high pending count in in-house Linux64 test pool

- Release Automation

- Please disable the servo bors cronjob

- Need an update watershed in 29.0bN for beta channel

- Tree closure hooks for esr31

- Releases

- Repos and Hooks

- Allow pushing Instantbird-only changes on a closed c-c- tree

- Create a script to import one Mercurial repository into a subdirectory of another, with linear history

- Add a repository hook to enforce new review requirements for changing .webidl files

- Tools

- update relman scripts based on notes from first usage

- Verify that trychooser's tryload is looking at the right names for pending jobs and adding them up into the correct buckets

- TryChooser conflicts with HTTPS Everywhere

- port b2g branching script to mozharness, with revision locking

- Update SlaveAPI sphynx docs to reflect recent changes

- Update tools/update-packaging/make_incremental_update.sh to allow passing Product Version and Channel ID

- Using slaveapi to reboot a machine on the slave health page results in "list index out of range" under 'output'

- loan jgriffin an AWS linux64 test box, and then bump up the instance cpu/ram til tests pass

- Balrog: Backend

- Buildduty

- loan glandium and mshal a Linux ec2 instance

- Growing pending queues for tegras and time between jobs per tegra > 6 hours

- [tracking] Eliminate buildduty

- Investigate Windows 8 machines that are still out of action

- Reconfigs should be automatic, and scheduled via a cron job

- mountain-lion talos systems using the wrong basedir

- General Automation

- [Tracking] Cleanup And organize mobile (sut) code.

- end_to_end reconfig script should run its python unbuffered

- Provide B2G Emulator builds for Darwin x86

- Figure out the correct path setup and mozconfigs for automation-driven MSVC2013 builds

- Move emulator gaia-ui-tests on cedar from AWS to IX slaves

- [Meta] Some "Android 4.0 debug" tests fail

- Create mozilla-esr31 branch

- Normalize builder names

- [Meta] Fix + unhide broken testsuites or else turn them off to save capacity

- gaia-try: do a merge locally instead of using the pull request reference

- manage_instance_storage.py should consider root volume size

- fx desktop builds in mozharness

- Move Firefox Desktop repacks to use mozharness

- Add signing for firefox and org.mozilla.updater binaries on OSX

- ensure the timezone and time are set properly on tegras (and other devices)

- Partial update generation service

- Run desktop mochitests-browser-chrome on Ubuntu

- Get Mulet builds running on OSX on fig

- port buildapi to relengapi

- Do nightly builds with profiling disabled

- Tracking bug for 21-jul-2014 migration work

- dolphin full image size is incorrect in pvt build

- spidermonkey_build.py looks for gcc in two different places

- Attach a cost figure(in USD) to try reports

- Please add non-unified builds to mozilla-central

- Allow to install additional packages in mock

- Stop rebooting after every job

- Schedule Android 4.0 Debug reftests, crashtests, and robocop tests on all trunk trees and let them ride the trains

- revamp b2g upload configs

- Hazard builds uploading to wrong FTP dir

- Schedule Mnw on cedar on emulator-jb and emulator-kk

- We should stop using setup.sh in tooltool

- Touch CLOBBER on branches being uplifted

- reduce EBS writes by tweaking writeout

- Improve slaveapi logging

- Loan Requests

- loan windows 7 slave to jmaher

- loan linux32 (hardware) slave to jmaher

- Loan t-w732-ix-003, t-w732-ix-004 to Q

- Loan :sfink a linux64 b-linux64-hp-0024

- Need a bld-lion-r5 to test build times with SSD

- Request to borrow an r4 mini

- Other

- Identify next batch of locales which no longer need nightlies on m-c

- Decide and document how many B2G filesystem diffs we keep for updates

- Create a long term archive of opt+debug builds on M-I for Regression Hunting

- mozharness device mixin has various problems

- Locate and identify tegra-122, tegra-123, and tegra-161

- mozharness device_talosrunner has some minor issues

- Set up cron jobs to copy tinderbox-builds content to S3

- [Tracking bug] support git in production on parity with hg

- get a consistent story on graph server data per branch

- [tracking] infrastructure improvements

- Platform Support

- Stop update_shared_repos runner task from pulling Try

- Deploy NSIS 3.0a2 or MozillaBuild 1.9 (includes NSIS 3.0a2) to buildslaves

- [tracker] Stop testing on tegras

- evaluate mac cloud options

- b-2008-sm machines being incorrectly flagged as unreachable

- signing win64 builds is busted

- implement c3.xlarge slave class for Linux64 test spot instances

- Investigate alternative SSH daemon for Windows

- verify script called by mozharness for android devices doesn't reboot via mozpool

- Deploy hg.m.o/build/buildbot production-0.8 to non-windows buildslaves to pick up bug 961075

- disable tegras on 32 to ride the trains

- slave pre-flight tasks

- Tegra Cleanup should delete some additional files on the sdcard

- Cleanup org.mozilla.f3nn3c.PasswordsProvider in verify.py

- Release Automation

- release automation should update ship it at certain points

- Update channels for single locale Beta and Release builds of Firefox for Android 30 (and beyond)

- use a property other than speed to differentiate between slaves in slavealloc

- Add new table(s) to shipit database

- send e-mail to release-drivers when a build is requested through ship it

- Add a standalone process that listens to pulse for release related buildbot messages

- Add REST API entry point to shipit that allows shipit-agent to enter release data into shipit database

- Stop doing a recursive chmod on directories every time we upload to a candidates dir

- Releases

- Releases: Custom Builds

- Repos and Hooks

- Error when pushing to user repo: Sending messages to pulse.mozilla.org, Hook returned an exception: 'NoneType' object has no attribute 'filerev'

- Change the webidl hook to allow commits authored by a DOM reviewer

- research if we can remove duplicate single head hg.m.o hook

- Tools

- Fix tools/update-packaging/common.sh for consistent behaviour across platforms

- Intermittent time travel in legacy vcs

- AWS Sanity Check lies about how long an instance was shut down for...

- Figure out tools versioning for partial generation

- tooltool upload should set file permissions to world readable

- tegra/panda health checks (verify.py) should not swallow exceptions

- Set up auto publish of doc index per Boston workweek agreement

- aws_create_instance should not be allowed to run forever

- mozharness mozilla-release merge day script

- Create a new landing page for releng

- mozharness mozilla-beta + mozilla-aurora merge day script

- slaveapi's shutdown_buildslave action doesn't cope well with a machine that isn't connected to buildbot

- self-serve agents' error handling needs more care

- Make mozharness use structured logging for marionette tests

- implement 'aws_create_instance' action in slaveapi

- [tracking] Implement a comprehensive slave health tool

- slaveapi should make use of dev staging inventory and mozdns/api/v1_dns

- Transplant tool (Hg to Hg) for sheriffs

http://relengofthenerds.blogspot.com/2014/07/this-week-in-mozilla-releng-july-4-2014.html

|

|

Christie Koehler: It’s the 4th of July and I’m Celebrating Independence from Facebook |

I just requested that Facebook permanently delete my account.

This change is a long time coming. I’ve grown increasingly concerned about the power Facebook exercises to commodify and influence our social interactions. There’s nothing holding Facebook accountable in the exercise of this power. Aside from all of that, I get very little out of time spent on the site. Yes, it’s a way I can connect with some folks for which I’m not in the habit of calling, emailing or writing. There’s nothing stopping me from doing this, however. I have the phone numbers, emails and addresses of the folks I generally care about keeping in touch with. I do wish more folks had their own blogs, though.

Earlier in the week I posted a message on my timeline telling folks that in a few days I’d be deleting my account. I listed a few other ways to get in touch with me including twitter, my blog, and email. The other thing I did was look at the settings for every Facebook page I’m an admin on and ensure I wasn’t the only one (I wasn’t). I also downloaded a copy of my info.

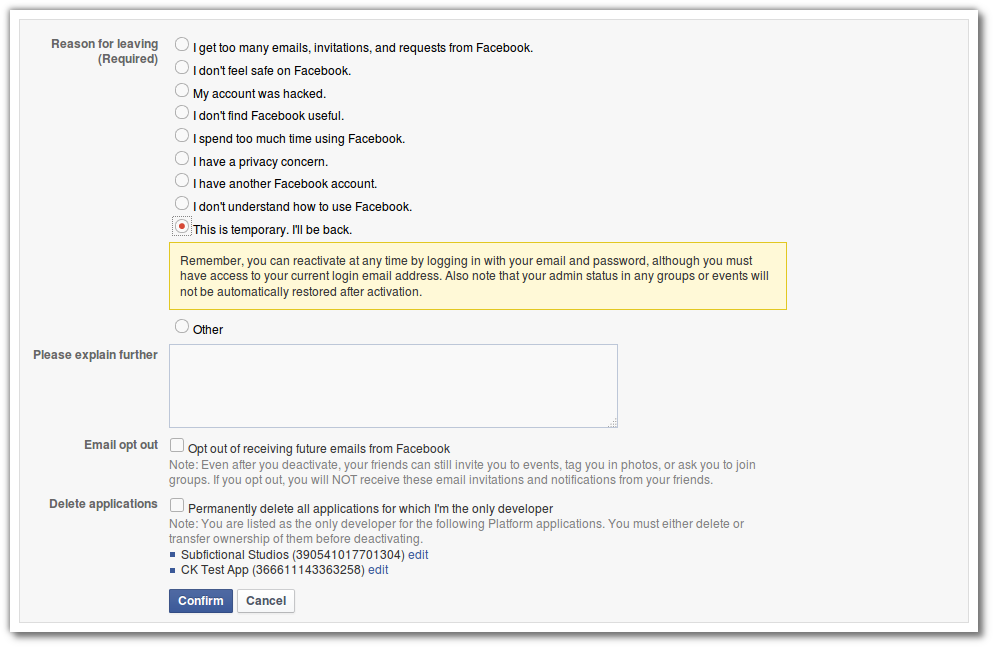

Today I logged in, ready to delete my account. First I couldn’t find a way to do so. I noticed a “deactivate my account” link under security settings. I figured this was the only way, so I tried it first.

When you try to deactivate your account, Facebook presents you with a page that does everything to try and get you to keep your account active. It shows you pictures of your friends, says they will miss you and prompts you to message them. I found it particularly funny that one of the friends it showed me was Creepius the Bear (and identity created to demonstrate how creepy one can be on Facebook):

Creepius will miss me after I’ve left Facebook.

Creepius will miss me after I’ve left Facebook.And then after this you must provide a reason you’re deactivating your account. For any reason you select, you’re given additional information that supposedly resolves the concern:

Facebook wants to know why you’re deactivating your account.

Facebook wants to know why you’re deactivating your account.What caught my attention was the Email opt out option, which states:

Note: Even after you deactivate, your friends can still invite you to events, tag you in photos, or ask you to join groups.

Not what I wanted, so I started figuring out how to work around this. Unfriend everyone first? Sounds tedious. Then someone asks me in IRC, “why don’t you delete instead of deactivate?” I responded saying I didn’t know that was an option. So, I searched Facebook’s help for “deactivate my account” and found this help page: How do I permanently delete my account?

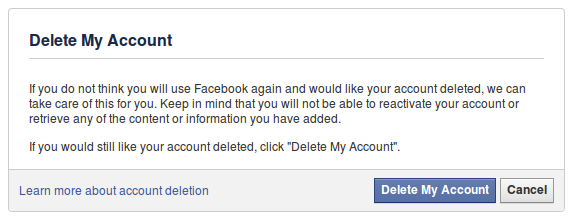

I follow the link in that article, and got this prompt:

Deleting my facebook account.

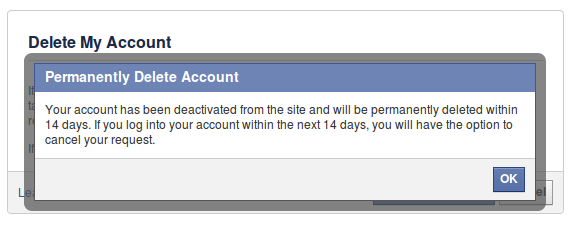

Deleting my facebook account.Much nicer, right? No guilt-trips and attempts to invalidate address my concerns. I clicked “Delete My Account”, filled out my password and captcha and got the following confirmation:

Confirmation that my account has been deactivated and will then be deleted

Confirmation that my account has been deactivated and will then be deletedI also received confirmation via email.

So, that’s it! Assuming I don’t log in to my account during the next 14 days, my account will be deleted. Ah, freedom!

If you like the idea of doing this, but want a more gradual approach, check out de-facing, in which one person talks about their plan to leave Facebook one friend at a time.

|

|

Vaibhav Agrawal: GSoC 2014: Progress Report |

In the last month, a good deal of work has been done on the Mochitest Failure Investigator project. I have described the algorithms implemented for bisecting the tests in my previous post. Since then, I have worked on including “sanity-check” once the cause of failure is found in which the tests are re-run omitting the cause of failure. The advantage of doing this is that if suppose a test is failing due to >1 number of previous tests, then we can find all those tests which are causing the failure. I then worked on refactoring the patch to integrate it seamlessly with the existing code. Andrew and Joel gave me good suggestions to make the code more beautiful and readable, and it has been a challenging and a great learning experience . The patch is now in the final review stages and it is successfully passing for all platforms on tbpl: https://tbpl.mozilla.org/?tree=Try&rev=07bbcb4a3e98. Apart from this, I worked on a small fun bug (925699) which was not cleaning up the unwanted temporary files, eventually occupying a large space on my machine.

Now since the proposed project is almost over and I still have a month and a half left, after discussing with my mentor, I am planning to cover up a few extra things:

* support finding the cause of failure in case of a timeout/crash for a chunk

* support for intermittent problems – this case is interesting, as we may be able to support AutoLand by using this.

* validating new tests to reduce intermittent problems caused by their addition.

Until next time!

https://vaibhavag.wordpress.com/2014/07/04/gsoc-2014-progress-report/

|

|

Jennie Rose Halperin: On working open in a closed world |

At Mozilla, we talk a lot about how working in the open can benefit our communities. As Mozillians, we come from a lot of different backgrounds and experience levels in terms of “openness,” and have blogged and blogged and blogged about this subject, trying to fight “community debt” and keep people active and involved using open processes to collaboration. As David Boswell pointed out at a recent talk, a lot of this is the expanding nature of our communities; while he was able to reach out to one or two people when he wanted to get involved fifteen years ago, now there are hundreds of listservs and tools and thousands of people to engage with.

At Ada Camp this weekend, I had a wonderful conversation with other feminists about hospitality and its absence in many communities. Working open is, for me, a form of hospitality. When we use phrases like “Designing for Participation,” we are actually inviting people into our work and then gifting it to them, asking them to share in our creativity, and using the power of the collective “hive” mind in order to create something beautiful, functional, and delightful. We should be continuing to embrace this gift economy, recognizing contributors in ways that they both want, and in perhaps less tangible ways.

There’s a section of the book The Ethical Slut (pardon the title) that I’ve always loved. The authors propose that love and affection in our society is engaged a mythical “starvation economy” and claim that many of us have been conditioned since childhood to “fight for whatever we get, often in cutthroat competition with our brothers and sisters.” They assert that people who believe in starvation economics are often possessive of their work, friends, and things, believing that anything they get has to come from “a small pool of not-enough” and has to be taken from someone else. Further, anything that they have can only be taken from them rather than shared.

I believe that creativity can be conceived of in a similar fashion. If there’s anything that working for Mozilla has taught me, it is that there are always enough (usually too many!) ideas to go around. Embracing creativity as a collaborative process is central to our ethos, and working “default open” should not just be about the final work, it should be also about the journey to get there. Inviting people to provide input into the story as well as the final product will not only make our events, projects, and products better, it will inspire a new kind of work and motivate our communities to find their impact because they have a say in the projects and products they love.

While making project pages public, inviting volunteers to meetings and workweeks, and using public forums rather than personal emails are a start to working in the open, there is still so much more that we can be doing to ensure that a multitude of voices are included in our process. We can learn a lot from other open source communities, but I would posit that we can also be learning from activist communities, non-profits, corporate trainings, and others. We’ve already begun with our speaker series “Learning from other non-profits,” but I look forward to seeing how much more we can do. Breaking down the silos can help us empower and grow our communities in ways we didn’t think possible.

As the community building team asserts,

Mozilla has reached the limits of unplanned, organic community growth.

For many people, one-on-one and personal interaction is the most important part of community, and until we create processes for creating and maintaining these connections as well as systems for mediating the inevitable conflicts that arise within communities working together toward a common goal, we have failed as advocates and community builders.

To that end, I am working with my colleagues to bring process-based solutions into conversation and indeed into the structure of the organization. From Mozilla “guides” who will help contributors find their way in an increasingly confusing contributor landscape to training in non-violent communication and consensus, we want to provide our communities open solutions that make them want to continue contributing and creatively collaborating together. We can do other things as well, like running exciting meetings with innovative structures, providing fun tasks to volunteers, and keeping personal connections vivid and electric with possibility.

On holidays, many Jews traditionally open the door and make a plate for any person who has no place to go. Reinterpreting that for our own creative processes, I would say that we should open the door and leave a place in our work for new people and new ideas because, as we have seen, there is enough. There is always enough.

|

|

Laura Hilliger: Updates from the edge |

My brain was doing this all week. via Giphy[/caption]

I collaborated with Doug to figure out the nuances of Webmaker Training and what it means for counting contribution towards the Mozilla project. I collected loads of data and wrote a couple of wiki pages that fully unpack the training that took place from May 12th June 8th. This debrief page talks about things went right, things went wrong and some ideas for improvement. This page explores how training is different from other types of programs in terms of how it relates to a contribution to the Mozilla project.

Another thing that I accomplish this week was taking a good deep dive into MDN’s new Learning Zone that they're putting together. I'm excited about this work because I think that the MDN community and Webmaker community have a lot of overlap. We can help each other in learning social and technical skills around the web, and we can help each other #TeachTheWeb too. I'd like to create more bridges, and the Learning Zone work is a step in that direction. The MDN is beginning to create articles and Makes that relate to the Web Literacy Map. They’re also starting to think about Thimble, Popcorn and X-ray goggles Makes that support active learning. They’re planning on making tutorials and other fun things for our community to remix or use to #TeachTheWeb.

I've also just been added to an email chain about the new Connected Learning Course that is going to be coming out in September. I’m looking forward to exploring cMOOC challenges and spinning ideas about blended learning along with the team putting together this new experience designed to create better ties between academic classrooms and online learning initiatives.

For more info on what I do every week, you can always check out my Weeknotes, and I'm all over the web, so get in touch!

My brain was doing this all week. via Giphy[/caption]

I collaborated with Doug to figure out the nuances of Webmaker Training and what it means for counting contribution towards the Mozilla project. I collected loads of data and wrote a couple of wiki pages that fully unpack the training that took place from May 12th June 8th. This debrief page talks about things went right, things went wrong and some ideas for improvement. This page explores how training is different from other types of programs in terms of how it relates to a contribution to the Mozilla project.

Another thing that I accomplish this week was taking a good deep dive into MDN’s new Learning Zone that they're putting together. I'm excited about this work because I think that the MDN community and Webmaker community have a lot of overlap. We can help each other in learning social and technical skills around the web, and we can help each other #TeachTheWeb too. I'd like to create more bridges, and the Learning Zone work is a step in that direction. The MDN is beginning to create articles and Makes that relate to the Web Literacy Map. They’re also starting to think about Thimble, Popcorn and X-ray goggles Makes that support active learning. They’re planning on making tutorials and other fun things for our community to remix or use to #TeachTheWeb.

I've also just been added to an email chain about the new Connected Learning Course that is going to be coming out in September. I’m looking forward to exploring cMOOC challenges and spinning ideas about blended learning along with the team putting together this new experience designed to create better ties between academic classrooms and online learning initiatives.

For more info on what I do every week, you can always check out my Weeknotes, and I'm all over the web, so get in touch!

|

|

Byron Jones: bugzilla and performance, 2014 |

bugzilla is a large legacy perl application initially developed at the birth of the world wide web. it has been refactored significantly in the 15 years since its release; however, some design decisions made at the start of the project carry significant technical debt in today’s modern web.

while there have been a large number of micro-optimisations over the course of bugzilla’s life (generally as a result of performance profiling), there are limits to the benefits these sorts of optimisations can provide.

this year has seen a lot of focus on improving bugzilla’s performance within mozilla, centred around the time it takes to display a bug to authenticated users.

tl;dr bugzilla is faster

memcached

the design of a modern large web application is generally centred around caches, between the business logic layer and the data sources, as well as between the users and the user interface. while bugzilla has been refactored to use objects, database abstraction, templates, etc, it had zero caching capabilities. this coupled with completely stateless processing of each request meant that every byte of html returned to the user was regenerated from scratch, starting with a new connection to the database.

towards the end of 2013 i worked on implementing a memcached framework into bugzilla [bug 237498].

retrofitting a caching mechanism into a large extendible framework proved to be a significant challenge. bugzilla provides the ability for developers to extend bugzilla’s functionality via extensions, including but not limited to adding new fields, user interface, or process. the extensions system conflicts with caching as it’s possible for an extension to conditionally alter an object in ways that would render it impossible to cache (eg. add a new field to an object only if the current user is a member of a particular group).

some compromises had to be made. instead of caching fully constructed objects, the cache sits between the object’s constructor and the database. we avoid a trip to the database, but still have to construct objects from that data (which allows extensions to modify the object during construction).

code which updated the database directly instead of using bugzilla’s objects had to be found and rewritten to use the objects or updated to manually clear the cache entries. extra care had to be taken as returning stale data could silently result in data loss. to placate concerns that these errors would be impossible to detect, the caller of an object’s constructor must pass in a parameter to “opt-in” to caching.

in 2014 i built upon the memcached framework to support most of bugzilla’s objects [bug 956233], with the “bugs” object being the only notable exception. memcached also caches bugzilla’s configuration parameters (classifications, products, components, groups, flags, …) [bug 987032]. although caching the “bugs” object would be beneficial given its central role in all things bugzilla, it is highly likely that enabling this by default would break bugzilla extensions and customisations as a high proportion of them update the database directly instead of using bugzilla’s object layer. this would manifest as data which is silently stale, making undetectable dataloss a high probability.

memcached support will be released with bugzilla 5.0, but has been live on bugzilla.mozilla.org (bmo) since february 2014.

instrumentation

while profilling tools such as nytprof have often been pointed at bugzilla, bmo’s high number of concurrent requests and usage patterns time and time again resulted in performance optimisations performing worse than expected once deployed to production.

we took the decision to deploy instrumentation code into bugzilla itself, reporting on each http request, database query, and template execution. as bugzilla is written in perl, support was absent for off-the-shelf instrumentation tools such as new relic, so we had to roll our own data collection and reporting system [bug 956230].

the collector wraps specific Bugzilla::DB, Bugzilla::Memcached and Bugzilla::Template calls via subclassing, then reports data to an elasticsearch cluster. currently all reporting solutions are ad-hoc and involve running of scripts which identify the most costly database queries and templates.