Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Myk Melez: The Once And Future GeckoView |

GeckoView is an Android library for embedding Gecko into an Android app. Mark Finkle introduced it via GeckoView: Embedding Gecko in your Android Application back in 2013, and a variety of Fennec hackers have contributed to it, including Nick Alexander, who described a Maven repository for GeckoView in 2014. It’s also been reused, at least experimentally, by Joe Bowser to implement MozillaView – GeckoView Proof of Concept.

But GeckoView development hasn’t been a priority, and parts of it have bitrotted. It has also remained intertwined with Fennec, which makes it more complicated to reuse for another Android app. And the core WebView class in Android (along with the cross-platform implementation in Crosswalk), already address a variety of web rendering use cases for Android app developers, which complicates its value proposition.

Nevertheless, it may have an advantage for the subset of native Android apps that want to provide a consistent experience across the fragmented Android install base or take advantage of the features Gecko provides, like WebRTC, WebVR, and WebAssembly. More research (and perhaps some experimentation) will be needed to determine to what extent that’s true. But if “there’s gold in them thar hills,” then I want to mine it.

So Nick recently determined what it would take to completely separate GeckoView from Fennec, and he filed a bunch of bugs on the work. I then filed meta-bug 1291362 — standalone Gradle-based GeckoView libary to track those bugs along with the rest of the work required to build and distribute a standalone Gradle-based GeckoView library reusable by other Android apps. Nick, Jim Chen, and Randall Barker have already made some progress on that project.

It’s still early days, and I’m still pursuing the project’s prioritization (say that ten times fast). So I can’t yet predict when we’ll complete that work. But I’m excited to see the work underway, and I look forward to reporting on its progress!

https://mykzilla.org/2016/09/14/the-once-and-future-geckoview/

|

|

Julia Vallera: Share your expertise with Mozilla Clubs around the world! |

Club guides are an important part to the Mozilla Clubs program as they provide direction and assistance for specific challenges that clubs may face during day-to-day operation. We are looking for volunteers to help us author new guides and resources that will be shared globally. By learning more about the process and structure of our guides, we hope that you’ll collaborate on a Mozilla club guide soon!

Background

In early 2015, Mozilla Clubs staff began publishing a series of guides that provide Club leaders with helpful tips and resources they need to maintain their Clubs. Soon after, community members began assisting with, collaborating on and authoring these guides alongside staff.

Guides are created in response to inquiries from Club Captains and Regional Coordinators around challenges they face within their clubs. Some challenges are common across Clubs and others are specific to one Club. In either case, the Mozilla Clubs team tries to create guides that assist in overcoming those challenges. Once a guide is published, it is listed as a resource on the Mozilla Clubs’ website.

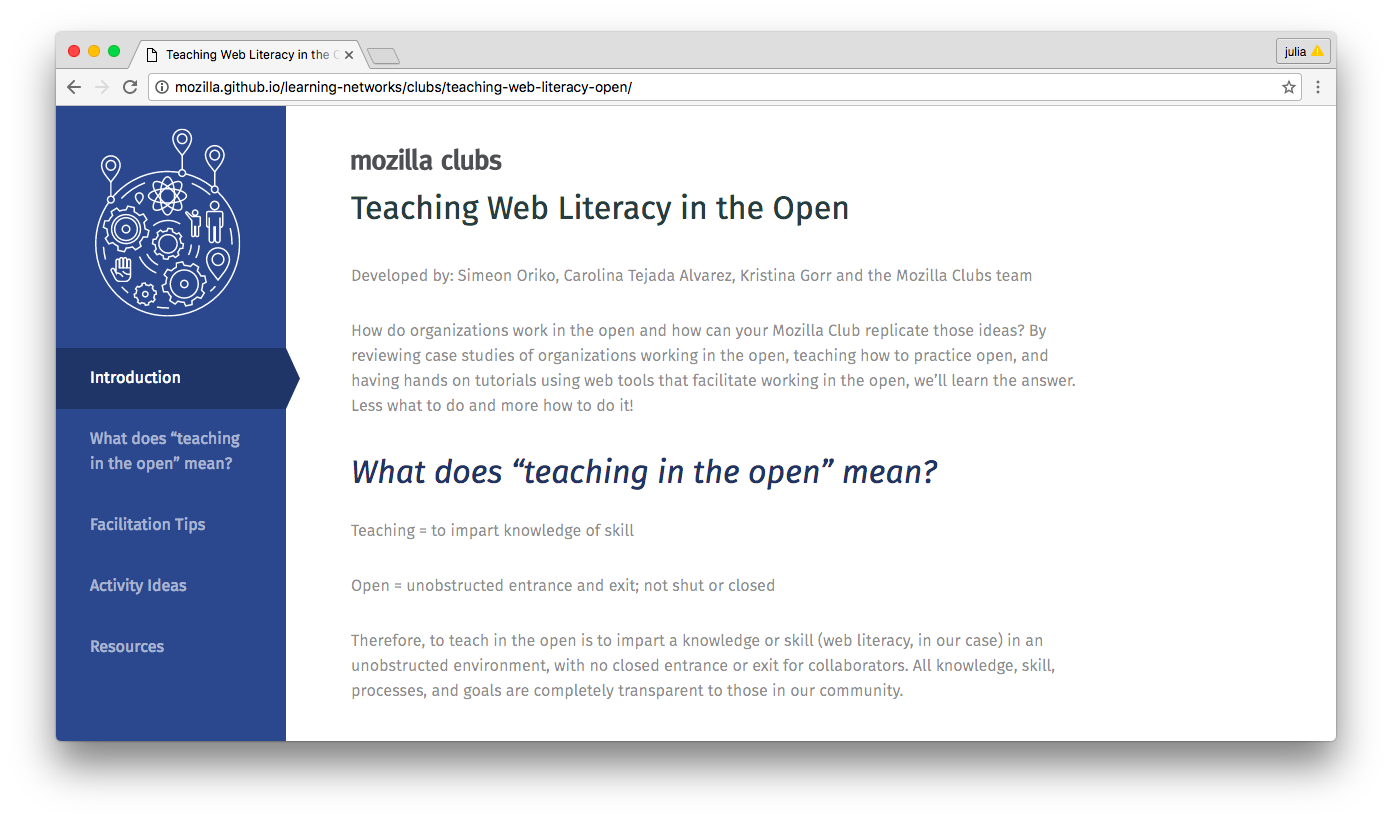

Screenshot of a guide co-authored by Simeon Oriko, Carolina Tejada Alvarez, Kristina Gorr and the Mozilla Clubs team

How are club guides used around the world?

At Mozilla Clubs, there is a growing list of guides and resources that help Club participants maintain Club activity around the world. These guides are in multiple languages and cover topics related to teaching the web, sustaining communities, growing partnerships, fostering collaborations and more.

Guides should be used and adapted as needed. Club leaders are free to choose which guides they use and don’t use. The information included in each guide is drawn from experienced community leaders that are willing to share their expertise. Guides will continue to evolve and we welcome suggestions for how to improve them. The source code, template and content are free and available on Github.

Here are a few examples of how guides have been used:

- A new Club Captain is wondering how to teach their Club learners about open practices so they read the “Teaching Web Literacy in the Open” guide for facilitation tips and activity ideas.

- A librarian is interested in starting a Club in a library and uses the “Hosting a Mozilla Club in your Library” guide for tips and event ideas.

- A Club wants to a make a website, so they use the “Creating a website” guide to learn how to secure a domain, choose a web host and use a free website builder.

What is the process for creating club guides?

The process for creating guides is evolving and sometimes varies on a case-by-case basis. In general, it goes something like this:

Step 1: Club leaders make suggestions for new guides on our discussion forum.

Step 2: Mozilla Club staff respond to the suggestion and share any existing resources.

Step 3: If there are no existing resources, the suggestion is added to a list of upcoming guides.

Step 4: Staff seek experts from the community to contribute or help author the guide (in some cases this could be the person who made the suggestion).

Step 5: Once we find an expert (internal to Mozilla or a volunteer from the community) who is interested in collaborating, the guide is drafted in as little or as much time as needed.

We currently have 50+ guides and resources available and look forward to seeing that number grow. If you have ideas for guides and/or would like to contribute to them, please let us know here.

http://www.juliavallera.com/blog/share-your-expertise-with-mozilla-clubs-around-the-world/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Commission Proposal to Reform Copyright is Inadequate |

The draft directive released today thoroughly misses the goal to deliver a modern reform that would unlock creativity and innovation in the Single Market.

Today the EU Commission released their proposal for a reformed copyright framework. What has emerged from Brussels is disheartening. The proposal is more of a regression than the reform we need to support European businesses and Internet users.

To date, over 30,000 citizens have signed our petition urging the Commission to update EU copyright law for the 21st century. The Commission’s proposal needs substantial improvement. We collectively call on the EU institutions to address the many deficits in the text released today in subsequent iterations of this political process.

The proposal fails to bring copyright in line with the 21st century

The proposal does little to address much-needed exceptions to copyright law. It provides some exceptions for education and preservation of cultural heritage. Still, a new exception for text and data mining (TDM), which would advance EU competitiveness and research, is limited to public interest research institutions (Article 3). This limitation could ultimately restrict, rather than accelerate, TDM to unlock research and innovation across sectors throughout Europe.

These exceptions are far from sufficient. There are no exceptions for panorama, parody, or remixing. We also regret that provisions which would add needed flexibility to the copyright system — such as a UGC (user-generated content) exception and an flexible user clause like an open norm, fair dealing or fair use — have not been included. Without robust exceptions, and provisions that bring flexibility and a future-proof element, copyright law will continue to chill innovation and experimentation.

Pursuing the ‘snippet tax’ on the EU level will undermine competition, access to knowledge

The proposal calls for ancillary copyright protection, or a ‘snippet tax’. Ancillary copyright would allow online publishers to copyright ‘press publications’, which is broadly defined to cover works that have the purpose of providing “information related to news or other topics and published in any media under the initiative, editorial responsibility and control of a service provider” (Article 2(4)). This content would remain under copyright for 20 years after its publication — an eternity online. This establishment of a new exclusive right would limit the free flow of knowledge, cripple competition, and hinder start-ups and small- and medium-sized businesses. It could, for example, require bloggers linking out to other sites to pay new and unnecessary fees for the right to direct additional traffic to existing sites, even though having the snippet would benefit both sides.

Ancillary copyright has already failed miserably in both Germany and Spain. Including such an expansive exclusive right at the EU level is puzzling.

The proposal establishes barriers to entry for startups, coders, and creators

Finally, the proposal calls for an increase in intermediaries’ liability. Streaming services like YouTube, Spotify, and Vimeo, or any ISPs that “provide to the public access to large amounts of works or other subject-matter uploaded by their users” (Article 13(1)), will be obliged to broker agreements with rightsholders for the use of, and protection of their works. Such measures could include the use of “effective content recognition technologies”, which imply universal monitoring and strict filtering technologies that identify and/or remove copyrighted content. This is technically challenging — and more importantly, would disrupt the very foundations that make many online activities possible in the EU. For example, putting user generated content in the crosshairs of copyright takedowns. Only the largest companies would be able to afford the complex software required to comply if these measures are deemed obligatory, resulting in a further entrenchment of the power of large platforms at the expense of EU startups and free expression online.

These proposals, if adopted as they are, would deal a blow to EU startups, to independent coders, creators, and artists, and to the health of the internet as a driver for economic growth and innovation. The Parliament certainly has its work cut out for it. We reiterate the call from 24 organisations in a joint letter expressing many of these concerns and urge the European Commission to publish the results of the Related rights and Panorama exception public consultation.

We look forward to working toward a copyright reform that takes account of the range of stakeholders who are affected by copyright law. And we will continue to advocate for an EU copyright reform that accelerates innovation and creativity in the Digital Single Market.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2016/09/14/commission-proposal-to-reform-copyright-is-inadequate/

|

|

Luis Villa: Copyleft and data: databases as poor subject |

tl;dr: Open licensing works when you strike a healthy balance between obligations and reuse. Data, and how it is used, is different from software in ways that change that balance, making reasonable compromises in software (like attribution) suddenly become insanely difficult barriers.

In my last post, I wrote about how database law is a poor platform to build a global public copyleft license on top of. Of course, whether you can have copyleft in data only matters if copyleft in data is a good idea. When we compare software (where copyleft has worked reasonably well) to databases, we’ll see that databases are different in ways that make even “minor” obligations like attribution much more onerous.

- Card Puncher from the 1920 US Census.

How works are combined

In software copyleft, the most common scenarios to evaluate are merging two large programs, or copying one small file into a much larger program. In this scenario, understanding how licenses work together is fairly straightforward: you have two licenses. If they can work together, great; if they can’t, then you don’t go forward, or, if it matters enough, you change the license on your own work to make it work.

In contrast, data is often combined in three ways that are significantly different than software:

- Scale: Instead of a handful of projects, data is often combined from hundreds of sources, so doing a license conflicts analysis if any of those sources have conflicting obligations (like copyleft) is impractical. Peter Desmet did a great job of analyzing this in the context of an international bio-science dataset, which has 11,000+ data sources.

- Boundaries: There are some cases where hundreds of pieces of software are combined (like operating systems and modern web services) but they have “natural” places to draw a boundary around the scope of the copyleft. Examples of this include the kernel-userspace boundary (useful when dealing with the GPL and Linux kernel), APIs (useful when dealing with the LGPL), or software-as-a-service (where no software is “distributed” in the classic sense at all). As a result, no one has to do much analysis of how those pieces fit together. In contrast, no natural “lines” have emerged around databases, so either you have copyleft that eats the entire combined dataset, or you have no copyleft. ODbL attempts to manage this with the concept of “independent” databases and produced works, but after this recent case I’m not sure even those tenuous attempts hold as a legal matter anymore.

- Authorship: When you combine a handful of pieces of software, most of the time you also control the licensing of at least one of those pieces of software, and you can adjust the licensing of that piece as needed. (Widely-used exceptions to this rule, like OpenSSL, tend to be rare.) In other words, if you’re writing a Linux kernel driver, or a WordPress theme, you can choose the license to make sure it complies. Not necessarily the case in data combinations: if you’re making use of large public data sets, you’re often combining many other data sources where you aren’t the author. So if some of them have conflicting license obligations, you’re stuck.

How attribution is managed

Attribution in large software projects is painful enough that lawyers have written a lot on it, and open-source operating systems vendors have built somewhat elaborate systems to manage it. This isn’t just a problem for copyleft: it is also a problem for the supposedly easy case of attribution-only licenses.

Now, again, instead of dozens of authors, often employed by the same copyright-owner, imagine hundreds or thousands. And imagine that instead of combining these pieces in basically the same way each time you build the software, imagine that every time you have a different query, you have to provide different attribution data (because the relevant slices of data may have different sources or authors). That’s data!

The least-bad “solution” here is to (1) tag every field (not just data source) with licensing information, and (2) have data-reading software create new, accurate attribution information every time a new view into the data is created. (I actually know of at least one company that does this internally!) This is not impossible, but it is a big burden on data software developers, who must now include a lawyer in their product design team. Most of them will just go ahead and violate the licenses instead, pass the burden on to their users to figure out what the heck is going on, or both.

Who creates data

Most software is either under a very standard and well-understood open source license, or is produced by a single entity (or often even a single person!) that retains copyright and can adjust that license based on their needs. So if you find a piece of software that you’d like to use, you can either (1) just read their standard FOSS license, or (2) call them up and ask them to change it. (They might not change it, but at least they can if they want to.) This helps make copyleft problems manageable: if you find a true incompatibility, you can often ask the source of the problem to fix it, or fix it yourself (by changing the license on your software).

Data sources typically can’t solve problems by relicensing, because many of the most important data sources are not authored by a single company or single author. In particular:

- Governments: Lots of data is produced by governments, where licensing changes can literally require an act of the legislature. So if you do anything that goes against their license, or two different governments release data under conflicting licenses, you can’t just call up their lawyers and ask for a change.

- Community collaborations: The biggest open software relicensing that’s ever been done (Mozilla) required getting permission from a few thousand people. Successful online collaboration projects can have 1-2 orders of magnitude more contributors than that, making relicensing is hard. Wikidata solved this the right way: by going with CC0.

What is the bottom line?

Copyleft (and, to a lesser extent, attribution licenses) works when the obligations placed on a user are in balance with the benefits those users receive. If they aren’t in balance, the materials don’t get used. Ultimately, if the data does not get used, our egos feel good (we released this!) but no one benefits, and regardless of the license, no one gets attributed and no new material is released. Unfortunately, even minor requirements like attribution can throw the balance out of whack. So if we genuinely want to benefit the world with our data, we probably need to let it go.

So what to do?

So if data is legally hard to build a license for, and the nature of data makes copyleft (or even attribution!) hard, what to do? I’ll go into that in my next post.

http://lu.is/blog/2016/09/14/copyleft-and-data-databases-as-poor-subject/

|

|

Tantek Celik: #XOXOFest 2016: Ten Overviews & Personal Perspectives |

I braindumped my rough, incomplete, and barely personal impressions from XOXO 2016 last night: #XOXOfest 2016: Independent Creatives Inspired, Shared, Connected. I encourage you to read the following well-written XOXO overview posts and personal perspectives. In rough order of publication (or when I read them):

(Maybe open Ben Darlow’s XOXO 2016 Flickr Set to provide some visual context while you read these posts.)

- Casey Newton (The Verge): In praise of the internet's best festival, which is going away (posted before mine, but I deliberately didn’t read it til after I wrote my own first XOXO 2016 post).

- Sasha Laundy: xoxo from XOXO

- Nabil “Nadreck” Maynard: XOXO, XOXO

- Matt Haughey: Starving artists / Memories of XOXO 2016

- Courtney Patubo Kranzke: XOXO Festival Thoughts

- Zoe Landon: Hugs and Kisses / A Year of XOXO

- Clint Bush: Andy & Andy: The XOXO legacy

- Erin Mickelson: XOXO

- Dylan Wilbanks: Eight short-ish thoughts about XOXO 2016

- Doug Hanke: Obligatory XOXO retrospective

There’s plenty of common themes across these posts, and lots I can personally relate to. For now I’ll leave you with just the list, no additional commentary. Go read these and see how they make you feel about XOXO. If you had the privilege of participating in XOXO this year, consider posting your thoughts as well.

http://tantek.com/2016/257/b1/xoxofest-overviews-personal-perspectives

|

|

Mozilla Addons Blog: WebExtensions and parity with Chrome |

A core strength of Firefox is its extensibility. You can do more to customize your browsing experience with add-ons than in any other browser. It’s important to us, and our move to WebExtensions doesn’t change that. One of the first goals of implementing WebExtensions, however, is reaching parity with Chrome’s extension APIs.

Parity allows developers to write add-ons that work in browsers that support the same core APIs with minimum fuss. It doesn’t mean the APIs are identical, and I wanted to clarify the reasons why there are implementation differences between browsers.

Different browsers

Firefox and Chrome are different browsers, so some APIs from Chrome do not translate directly.

One example is tab highlight. Chrome has this API because it has the concept of highlighted tabs, which Firefox does not. So instead of browser.tabs.onHighlighted, we fire this event on the active tab as documented on MDN. It’s not the same functionality as Chrome, but that response makes the most sense for Firefox.

Another more complicated example is private browsing mode. The equivalent in Chrome is called incognito mode and extensions can support multiple modes: spanning, split or not_allowed. Currently we throw an error if we see a manifest that is not spanning as that is the mode that Firefox currently supports. We do this to alert extension authors testing out their extension that it won’t operate the way they expect.

Less popular APIs

Some APIs are more popular than others. With limited people and time we’ve had to focus on the APIs that we thought were the most important. At the beginning of this year we downloaded 10,000 publicly available versions of extensions off the Chrome store and examined the APIs called in those extensions. It’s not a perfect sample, but it gave us a good idea.

What we found was that there are some really popular APIs, like tabs, windows, and runtime, and there are some APIs that are less popular. One example is fontSettings.get, which is used in 7 out of the 10,000 (0.07%) add-ons. Compare that to tabs.create, which is used in 4,125 out of 10,000 (41.25%) add-ons.

We haven’t prioritized the development of the least-used APIs, but as always we welcome contributions from our community. To contribute to WebExtensions, check out our contribution page.

Deprecated APIs

There are some really popular APIs in extensions that are deprecated. It doesn’t make sense for us to implement APIs that are already deprecated and are going to be removed. In these cases, developers will need to update their extensions to use the new APIs. When they do, they will work in the supported browsers.

Some examples are in the extension API, which are mostly replaced by the runtime API. For example, use runtime.sendMessage instead of extension.sendMessage; use runtime.onMessage instead of extension.onRequest and so on.

W3C

WebExtensions APIs will never completely mirror Chrome’s extension APIs, for the reasons outlined above. We are, however, already reaching a point where the majority of Chrome extensions work in Firefox.

To make writing extensions for multiple browsers as easy as possible, Mozilla has been participating in a W3C community group for extension compatibility. Also participating in that group are representatives of Opera and Microsoft. We’ll be sending a representative to TPAC this month to take part in discussions about this community group so that we can work towards a common browser standard for browser extensions.

Update: please check the MDN page on incompatibilities.

https://blog.mozilla.org/addons/2016/09/13/webextensions-and-parity-with-chrome/

|

|

Armen Zambrano: Increasing test coverage |

Here's some of what I did:

- Read Python's page about increasing test coverage

- I wanted to learn what core Python recommends

- Tthey recommend is using coverage.py

- Quick start with coverage.py

- "coverage run --source=mozci -m py.test test" to gather data

- "coverage html" to generate an html report

- "/path/to/firefox firefox htmlcov/index.html" to see the report

- NOTE: We have coverage reports from automation in coveralls.io

- If you find code that needs to be ignored, read this.

- Use "# pragma: no cover" in specific lines

- You can also create rules of exclusion

- Once you get closer to 100% you might want to consider to increase branch coverage instead of line coverage

- Read more in here.

- Once you pick a module to increase coverage

- Keep making changes until you run "coverage run" and "coverage html".

- Reload the html page to see the new results

This work by Zambrano Gasparnian, Armen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/armenzg_mozilla/~3/KVxSo3fD85g/increasing-test-coverage.html

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Cybersecurity is a Shared Responsibility |

There have been far too many “incidents” recently that demonstrate the Internet is not as secure as it needs to be. Just in the past few weeks, we’ve seen countless headlines about online security breaches. From the alleged hack of the National Security Agency’s “cyberweapons” to the hack of the Democratic National Committee emails, and even recent iPhone security vulnerabilities, these stories reinforce how crucial it is to focus on security.

Internet security is like a long chain and each link needs to be tested and re-tested to ensure its strength. When the chain is broken, bad things happen: a website that holds user credentials (e.g., email addresses and passwords) is compromised because of weak security; user credentials are stolen; and, those stolen credentials are then used to attack other websites to gain access to even more valuable information about the user.

One weak link can break the chain of security and put Internet users at risk. The chain only remains strong if technology companies, governments, and users work together to keep the Internet as safe as it can be.

Technology companies must focus on security.

Technology companies need to develop proactive, pro-user cybersecurity technology solutions.

We must invest in creating a secure platform. That means supporting things like adopting and standardizing secure protocols, building features that improve security, and empowering users with education and better tools for their security.

At Mozilla, we have security features like phishing and malware protection built into Firefox. We started one of the first Bug Bounty programs in 2004 because we want to be informed about any vulnerabilities found in our software so we can fix them quickly. We also support the security of the broader open source ecosystem (not just Mozilla developed products). We launched the Secure Open Source (SOS) Fund as part of the Mozilla Open Source Support program to support security audits and the development of patches for widely used open source technologies.

Still, there is always room for improvement. The recent headlines show that the threat to user safety online is real, and it’s increasing. We can all do better, and do more.

Governments must work with technology companies.

Cybersecurity is a shared responsibility and governments need to do their part. Governments need to help by supporting security solutions that no individual company can tackle, instead of advancing policies that just create weak links in the chain.

Encryption, something we rely on to keep people’s information secure online everyday, is under attack by governments because of concerns that it inadvertently protects the bad guys. Some governments have proposed actions that weaken encryption, like in the case between Apple and the FBI earlier this year. But encryption is not optional – and creating backdoors for governments, even for investigations, compromises the security of all Internet users.

The Obama Administration just appointed the first Federal Chief Information Security officer as part of the Cybersecurity National Action Plan. I’m looking forward to seeing how this role and other efforts underway can help government and technology companies work better together, especially in the area of security vulnerabilities. Right now, there’s not a clear process for how governments disclose security vulnerabilities they discover to affected companies.

While lawful hacking by a government might offer a way to catch the bad guys, stockpiling vulnerabilities for long periods of time can further weaken that security chain. For example, the recent alleged attack and auction of the NSA’s “cyberweapons” resulted in the public release of code, files, and “zero day” vulnerabilities that gave companies like Cisco and Fortinet just that- zero days to develop fixes before they were possibly exploited by hackers. There aren’t transparent and accountable policies in place that ensure the government is handling vulnerabilities appropriately and disclosing them to affected companies. We need to make this a priority to protect user security online.

Users can take easy and simple steps to strengthen the security chain.

Governments and companies can’t do this without you. Users should always update their software to benefit from new security features and fixes, create strong passwords to guard your private information, and use available resources to become educated digital citizens. These steps don’t just protect people who care about their own security, they help create a more secure system and go a long way in making it harder to break the chain.

Working together is the only way to protect the security of the Internet for the billions of people online. We’re dedicated to this as part of our mission and we will continue our work to advance these issues.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2016/09/13/cybersecurity-is-a-shared-responsibility/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Meeting OpenData France 2 |

Meeting OpenData France.

Meeting OpenData France.

|

|

Mozilla Release Management Team: Firefox 49 delayed |

The original 2016 Firefox release schedule had the release of Firefox 49 shipping on September 13, 2016. During our release qualification period for Firefox 49, we discovered a bug in the release that causes some desktop and Android users to see a slow script dialog more often than we deem acceptable. In order to allow time to address this issue, we have rescheduled the release of Firefox 49 to September 20, 2016.

In order to accommodate this change, we will shorten the following development cycle by a week. No other scheduled release dates are impacted by this change.

In parallel, Firefox ESR 45.4.0 is also delayed by a week.

http://release.mozilla.org/firefox/49/2016/09/13/49-delayed.html

|

|

Tantek Celik: #XOXOfest 2016: Independent Creatives Inspired, Shared, Connected |

Inspired, once again. This was the fifth XOXO Conference & Festival (my fourth, having missed last year).

There’s too much about XOXO 2016 to fit into one "XOXO 2016" blog post. So much that there’s no way I’d finish if I tried.

4-ish days of:

Independent creatives giving moving, inspiring, vulnerable talks, showing their films with subsequent Q&A, performing live podcast shows (with audience participation!).

Games, board games, video games, VR demos. And then everything person-to-person interactive. All the running into friends from past XOXOs (or dConstructs, or classic SXSWi), meetups putting IRL faces to Slack aliases.

Friends connecting friends, making new friends, instantly bonding over particular creative passions, Slack channel inside jokes, rare future optimists, or morning rooftop yoga under a cloud-spotted blue sky.

The walks between SE Portland venues. The wildly varying daily temperatures, sunny days hotter than predicted highs, cool windy nights colder than predicted lows. The attempts to be kind and minimally intrusive to local homeless.

More conversations about challenging and vulnerable topics than small talk. Relating on shared losses. Tears. Hugs, lots of hugs.

Something different happens when you put that many independent creatives in the same place, and curate & iterate for five years. New connections, between people, between ideas, the energy and exhaustion from both. A sense of a safer place.

I have so many learnings from all the above, and emergent patterns of which swimming in my head that I’m having trouble sifting and untangling. Strengths of creative partners and partnerships. Uncountable struggles. The disconnects between attention, popularity, money. The hope, support, and understanding instead of judgment.

I'm hoping to write at least a few single-ish topic posts just to get something(s) posted before the energies fade and memories start to blur.

http://tantek.com/2016/256/b1/xoxofest-inspired-shared-connected

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: Sierraspoof is here |

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2016/09/sierraspoof-is-here.html

|

|

Mozilla Open Design Blog: The Conversation About Design Has Changed |

Like many of us in the design community, I’ve followed along in recent years as seemingly countless companies have undertaken the exciting and often fraught challenge of redesigning their visual identities. A quick glance at the Before/After section of Brand New, the well-known design blog dedicated to the critique of such things, shows 216 projects chronicled year-to-date.

Some redesigns have been well received like Google’s, while others have drawn an enormous amount of criticism from both the design community and the general public, such as Uber’s. These are interesting times for design as the critique of our work has moved from something those of us in the trade might discuss with colleagues over dinner, to something that anyone with an @handle and opinion can weigh in publicly over social media. On several occasions, this public discourse has taken such an extreme tone that Andrew Beck has described it as design crit as bloodsport.

Designing in the Open

Earlier this year I began consulting with non-profit Mozilla to tee up a logo redesign initiative. During that time, Mozilla’s Creative Director Tim Murray proposed the idea of designing in the open. His vision was to build off of the open source principles that are bedrock to Mozilla by applying them to the end-to-end process of an identity redesign. The idea was to be as transparent as possible with the process, the initial concepts, the refinement and the outcome, and to have an open, public dialog with many people as possible along the way. He would engage the typical stakeholders one would expect, such as Mozilla’s senior leadership, as well as Mozilla’s 10,000+ strong volunteer community. But Tim also wanted to reach beyond Mozillians. He invited not only the design community into the discussion, but anyone for whom the Mozilla mission – to keep the internet healthy, open and safe for all – resonates.

Initially, his proposal made me slightly uncomfortable. I felt a mix of caution and curiosity and I had to ask myself: why?

A Mix of Caution and Curiosity

I was concerned that opening up earlier stages of the design process to that kind of public commentary (think stakeholders at scale) would negatively affect the work. And my hesitancy was also rooted in a lack of understanding as to what Mozilla was asking from the design community. I questioned how we as designers could meaningfully participate in a public dialog about design work. After all, by submitting a professional opinion on everything from initial thinking, to design exploration through concept and execution, weren’t we engaging in a kind of spec work?

As for my curiosity, it was piqued by the opportunity to re-examine the methodology by which design outcomes are generated. Would a larger and more diverse conversation upfront in fact lead to a better outcome? And as design crit has gone mainstream and instantaneous thanks to social media, how can we show up in public conversations about design deliverables without compromising our point of view against spec work?

Where Things Stand Now

The identity redesign is now well underway. johnson banks was selected as the agency partner and Mozilla has indeed undertaken a fully transparent, moderated, and public design process. The first round creative concepts were shared a week ago and met with hundreds if not thousands of responses and a full news cycle in the design press.

While the end result of this unconventional approach remains uncertain, we do know that Tim and team created a process that is true to Mozilla’s open source beliefs and the manifesto that guides the company’s conduct. And we know they are willing to withstand the outcome even if it rises to the level of bloodsport. For that, they should be commended.

As for the questions raised about spec work and the Mozilla initiative, if you’re aligned with Mozilla’s mission and choose to provide critique then your participation as a practicing professional is an act of volunteerism. In their words…

“What we’re seeking is input on work that’s in process. We welcome your feedback in a form that suits you best, be it words, napkin sketches, or Morse Code. We simply want to incorporate as many perspectives and voices into this open design process as possible. We don’t take any single contribution lightly. We hope you’ll agree that by helping Mozilla communicate its purpose better through design, you’ll be helping improve the future Internet.”

As for the larger questions raised by increasing public dialog about design, it’s up to each of us personally to determine how we participate and when. But all industries experience change, design is no exception. By at least trying to understand Mozilla’s approach to this project and how it fits within a broader narrative, designers can use this as an opportunity to challenge long-held methodologies, and perhaps pave the way for new ones.

Republished with permission from AIGA SF / The Professional Association for Design

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons “And Phoebus’ Tresses Stream Athwart the Glade”

https://blog.mozilla.org/opendesign/the-conversation-about-design-has-changed/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Mozilla Weekly Project Meeting, 12 Sep 2016 |

The Monday Project Meeting

The Monday Project Meeting

https://air.mozilla.org/mozilla-weekly-project-meeting-20160912/

|

|

Luis Villa: Copyleft and data: database law as (poor) platform |

tl;dr: Databases are a very poor fit for any licensing scheme, like copyleft, that (1) is intended to encourage use by the entire world but also (2) wants to place requirements on that use. This is because of broken legal systems and the way data is used. Projects considering copyleft, or even mere attribution, for data, should consider other approaches instead.

- The original database: Hollerith Census Machine Dials, by Marcin Wichary, under CC BY 2.0.

I’ve been a user of copyleft/share-alike licenses for a long time, and even helped draft several of them, but I’ve come around to the point of view that copyleft is a poor fit for data. Unfortunately, I’ve been explaining this a lot lately, so I want to explain why in writing. This first post will focus on how the legal system around databases is broken. Later posts will focus on how databases are hard to license, and what we might do about it.

FOSS licensing, and particularly copyleft, relies on legal features database rights lack

Defenders of copyleft often have to point out that copyleft isn’t necessarily anti-copyright, because copyleft depends on copyright. This is true, of course, but the more I think about databases and open licensing, the more I think “copyleft depends on copyright” almost understates the case – global copyleft depends not just on “copyright”, but on very specific features of the international copyright system which database law lacks.

To put it in software terms, the underlying legal platform lacks the features necessary to reliably implement copyleft.

Consider some differences between the copyright system and database law:

- Maturity: Copyright has had 100 or so years as an international system to work out kinks like “what is a work” or “how do joint authors share rights?” Even software copyright law has existed for about 40 years. In contrast, database law in practice has existed for less than 20 years, pretty much all of that in Europe, and I can count all the high court rulings on it on my fingers and toes. So key terms, like “substantial”, are pretty hard to define-courts and legislatures simply haven’t defined, or refined, the key concepts. This makes it very hard to write a general-purpose public license whose outcomes are predictable.

-

Stability: Related to the previous point, copyright tends to change incrementally, as long-standing concepts are slowly adapted to new circumstances. (The gradual broadening of fair use in the Google era is a good example of this.) In contrast, since there are so few decisions, basically every decision about database law leads to upheaval. Open Source licenses tend to have a shelf-life of about ten years; good luck writing a database license that means the same thing in ten years as it does today!

-

Global nature: Want to share copyrighted works with the entire world? Copyright (through the Berne Convention) has you covered. Want to share a database? Well, you can easily give it away to the whole world (probably!), but want to reliably put any conditions on that sharing? Good luck! You’ve now got to write a single contract that is enforceable in every jurisdiction, plus a license that works in the EU, Japan, South Korea, and Mexico. As an example again, “substantial” – used in both ODbL and CC 4.0 – is a term from the EU’s Database Directive, so good luck figuring out what it means in a contract in the US or within the context of Japan’s database law.

-

Default rights: Eben Moglen has often pointed out that anyone who attacks the GPL is at a disadvantage, because if they somehow show that the license is legally invalid, then they get copyright’s “default”: which is to say, they don’t get anything. So they are forced to fight about the specific terms, rather than the validity of the license as a whole. In contrast, in much of the world (and certainly in the US), if you show that a database license is legally invalid, then you get database’s default: which is to say, you get everything. So someone who doesn’t want to follow the copyleft has very, very strong incentives to demolish your license altogether. (Unless, of course, the entire system shifts from underneath you to create a stronger default – like it may have in the EU with the Ryanair case.)

With all these differences, what starts off as hard (“write a general-purpose, public-facing license that requires sharing”) becomes insanely difficult in the database context. Key goals of a general-purpose, public license – global, predictable, reliable – are very hard to do.

In upcoming posts, I’ll try to explain why, even if it were possible to write such a license from a legal perspective, it might not be a good idea because of how databases are used.

http://lu.is/blog/2016/09/12/copyleft-and-data-database-law-as-poor-platform/

|

|

Jared Wein: Rethinking themes in Firefox |

A couple of weeks ago Mike de Boer and I started work on a project to rethink themes in Firefox. At present day, Firefox offers two ways for users to theme their browser: XUL themes (also known as “complete themes”) and lightweight themes (also known as “themes”). We want to create something that gives more power than lightweight themes while also being easier to create and maintain than XUL themes.

A couple of weeks ago Mike de Boer and I started work on a project to rethink themes in Firefox. At present day, Firefox offers two ways for users to theme their browser: XUL themes (also known as “complete themes”) and lightweight themes (also known as “themes”). We want to create something that gives more power than lightweight themes while also being easier to create and maintain than XUL themes.

Last week we published a survey asking theme authors and users what they like about themes and what they would change. To date, we have received over 250 detailed responses. We will be keeping the survey open and monitoring it for anybody that has not had a chance to reply yet. Here’s what we’ve learned:

Have you made a lightweight theme before?

21.8% yes

What do you like about lightweight themes?

A strong majority (70%) of lightweight theme authors said that they liked how lightweight themes were simple and easy to make. The next group, at 6%, said that they liked how lightweight themes always remain compatible after Firefox updates. 4% of users also liked that they were easy to install with no restart required. A couple people complained that they were too simple and there was too much spam in the themes section of the Add-ons website.

What do you feel was difficult to do or missing from lightweight themes?

A little less than (42%) half of responses would have liked to do more than just a couple of images with lightweight themes. They would like to apply background images to other parts of the browser, change icons, buttons, and the size-of and location of browser components. The next group of responses (10%) wanted more support for scaling, repetition, animation, and position of background images. Improved documentation (8%) and a lack of a development environment such as an in-browser editor followed (6%). The last two groups of responses wanted the ability for themes to change based on external factors (2%) and separate images for the tabs and tab toolbar (2%).

Have you made a XUL theme before?

23% yes

What do you like about XUL themes?

A strong majority of the respondents agreed firmly with 71.2% that XUL themes are awesome in allowing to touch and customize all the things. The second largest group of respondents seek out XUL themes because they offer more nuts and bolts to tinker with than lightweight themes at 11.5%, while the familiarity with the CSS styling language is the main reason to like them for 7.7% of the respondents. Two other notable groups are people who like dark themes, which are apparently only really available as XUL themes, and ones who feel that XUL themes are the easiest thing to make on this planet, each at 3.9%.

What do you feel was difficult to do or missing from XUL themes?

The largest amount of responses (29.8%) said that it is a real pain to keep these themes up-to-date and working, with the current fast release cycle of Firefox and the fast pace of development. 28.1% of the respondents rightfully complained that they need to use exotic, undocumented technologies and unknown CSS selectors in order to create a working XUL theme. Whilst 15.8% claimed there is nothing wrong with XUL themes and we should keep it as-is, another 12.3% is sad about the lack of documentation or any kind of manual to get started. Packaging and delivery of XUL themes is not considered optimal by 10.5% of respondents and that ultimately very few of these themes can be configured after installation (3.5%).

Why do you install themes?

About half (47%) of the survey responses want to personalize Firefox. These people said that they want to make Firefox “their own” and have fun showing it off. They enjoy having full control over the user interface through XUL themes and like the ability to set arbitrary CSS. The next set of responses (16%) asked for a “dark” Firefox, making it easier on the eyes at night. These responses were generally focused on the toolbars and menus of the browser being dark. At 12% of responses was closer integration with the operating system followed closely by 11% of responses saying that they felt the default theme was boring and bland. The last category of responses that received multiple votes was to allow themes to undo recent changes to the user interface, as an attempt to keep things the same that they’ve been for the past months/years.

What capabilities would you like themes to have?

More than half (56%) of the survey responses want full control over the browser UI. They would like to move and hide items, change tab shapes, replace icons, context menus, scrollbars, and more. Following this large group, we had close to 5% of respondents who wanted to simply change basic colors and another group, also close to 5%, that wanted to make it easy for users to make simple tweaks to their browser or an installed theme through a built-in menu or tool. Native OS integration, such as using platform-specific icons and scrollbars, followed closely at 3%. Also at 3% of responses were requests from users who require larger icons and improved readability of the browser’s user interface for improved accessibility. Not far behind, and ironically next in the order of responses, were requests for a smaller browser UI (2%). These users generally want to maximize the amount of screen space that web pages can use. Both “dark themes” and “themes not breaking with future releases” got 2% of responses. In our last group of responses at or above 1% was themes that could change based on external factors (time of day, season, month, web color, or a very slow animation), restartless and easy to trial, ability to apply multiple themes to create a “mash-up”, and to lighten the tab bar.

What parts of Firefox are most important to you to be able to change the appearance of? Why?

Almost 20% of the respondents can not make a choice between the parts of Firefox and thus want to customize the app in its entirety. Following closely with 16% is the group of respondents that think the tabs area is the most important part for themes, while half that number choose toolbars, (toolbar)button icons and the area above the tabs, including the window decoration and window controls. Interestingly, the wish to be able to theme in-content pages is as strong as that of the Awesomebar and respective navigation controls: 6.8%. Changing the colors, palette and fonts used for the UI are the other most notable choices from the community of respondents at 6.4% and 4%, respectively.

Are there theme-related features from other browser or apps that you would like to see incorporated into Firefox?

An overwhelming majority of the respondents insist that we don’t need to change a thing and that other apps don’t offer grand alternatives at 36.5%, or simply can’t think of any. The Vivaldi browser came up in our preliminary research and also takes a prominent position as device of inspiration for theming features at 11.2%. A dark theme like other apps already offer in their package (5.9%), applying tints of color on SVG icons and background masks (2.9%) on UI elements – most notably the titlebar – and take Opera’s about:newtab theming capabilities (2.4%). A notable response from 2.9% of respondents was to introduce a live theme editor in Firefox with sharing capabilities, so that theme creators can take existing themes to tweak to their own liking and (re-)share with others.

The grouping of the results and more details can be found in our meeting notes. Our full archive of meeting notes is also publicly viewable.

Tagged: firefox, planet-mozilla, themes

https://msujaws.wordpress.com/2016/09/12/rethinking-themes-in-firefox/

|

|

Mozilla Open Innovation Team: Introducing the Open Innovation Toolkit |

Innovation is part of our DNA at Mozilla. It’s not just about making products that support the open web, but how we make those products — with a transparent and participatory approach.

There’s a paradox in open innovation. On one hand, the diversity of an open community demonstrably increases the quality of solutions. On the other hand, using best practices like human-centered design across a distributed team can be hard work. But in order to maintain high quality of experience, solve real user problems and ultimately create great products that people want, it must be done.

To help address this, we’ve been developing the Open Innovation Toolkit.

Open Innovation Toolkit Site

Open Innovation Toolkit SiteIt is a community-sourced set of best practices and methods that incorporate human-centered design into a open source product development process. It consists of a collection of easy-to-use, self-serve techniques that are gathered from industry best practices. They’re not ‘new to the world’ but together they create a knowledge bank of methods that we at Mozilla have found useful and that build on some of best thinking in the industry.

We want to equip everyone in the Mozilla community — and beyond — with a set of useful and proven tools and a common vocabulary to incorporate human-centered design into their product development process.

We’ve learned and been inspired by other similar efforts, such as the Nesta’s DIY toolkit for social innovation, which has successfully been used by many global organisations from Women in Global Democracy to Kent city planning council. The servicedesigntools.org site (which started out as a masters project) became a great venue for sharing service design projects.

An overview of the current methods gathered from open source industry experts.

An overview of the current methods gathered from open source industry experts.More than anything, this toolkit is an invitation to everyone in open source product development, from developers to advocates, to use it, play with it and to give us feedback on use cases we might add.

Check out our first examples at https://toolkit.mozilla.org and contribute your ideas!

Introducing the Open Innovation Toolkit was originally published in Mozilla Open Innovation on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

QMO: Firefox 50.0 Aurora Testday Results |

Hello Mozillians!

As you may already know, last Friday – September 9th – we held a new Testday event, for Firefox 50.0 Aurora.

Thank you all for helping us making Mozilla a better place – Iryna Thompson, Survesh, Subhrajyoti, Kumaraguru, Karthikeyan, Nilima, gaby2300, Moin Shaikh.

From Bangladesh: Nazir Ahmed Sabbir, Rezaul Huque Nayeem, Samad Talukder, Asif Mahmud Shuvo, Kazi Nuzhat Tasnem, Sajedul Islam, Md.Majedul islam, Mohammad Abidur Rahman Chowdhury, Raihan Ali, Niaz Bhuiyan Asif, Sufi Ahmed Hamim, Saheda Reza Antora, Toki Yasir, Md. Almas Hossain, Nashrif Mahmud, Maruf Rahman.

A big thank you goes out to all our active moderators too!

Results:

- there were 18 verified bugs:

- there was 1 new issue found:

- some failures were mentioned in the etherpad; therefore, please add the requested details in the etherpad or, even better, join us on #qa IRC channel and let’s figure them out

https://quality.mozilla.org/2016/09/firefox-50-0-aurora-testday-results/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Meeting OpenData France 1 |

Meeting OpenData France.

Meeting OpenData France.

https://air.mozilla.org/meeting-opendata-france-Sept-12-2016/

|

|

Niko Matsakis: Thoughts on trusting types and unsafe code |

I’ve been thinking about the unsafe code guidelines a lot in the back

of my mind. In particular, I’ve been trying to think through what it

means to trust types

– if you recall from the

Tootsie Pop Model (TPM) blog post, one of the key examples

that I was wrestling with was the RefCell-Ref example. I want to

revisit a variation on that example now, but from a different

angle. (This by the way is one of those Niko thinks out loud

blog

posts, not one of those Niko writes up a proposal

blog posts.)

Setup

Let’s start with a little safe function:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

The question is, should the compiler ever be able to optimize this function as follows:

1 2 3 4 | |

By moving the load from v after the call to collaborator(), we

avoided the need for a temporary variable. This might reduce stack

size or register pressure. It is also an example of the kind of

optimizations we are considering doing for MIR (you can think of it as

an aggressive form of copy-propagation). In case it’s not clear, I

really want the answer to this question be yes – at least most of the

time. More specifically, I am interested in examining when we can do

this without doing any interprocedural analysis.

Now, the question of is this legal?

is not necessarily a yes or no

question. For example, the Tootsie Pop Model answer was it

depends

. In a safe code context, this transformation was legal. In an

unsafe context, it was not.

What could go wrong?

The concern here is that the function collaborator() might invalidate *v in

some way. There are two ways that this could potentially happen:

- unsafe code could mutate

*v, - unsafe code could invalidate the memory that

vrefers to.

Here is some unsafe code that does the first thing:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Here is some unsafe code that invalidates *v using an option (you

can also write code that makes it get freed, of course). Here, when we

start, data is Some(22), and we take a reference to that 22. But

then collaborator() reassigns data to None, and hence the memory

that we were referring to is now uninitialized.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

So, when we ask whether it is legal to optimize patsy move the *v

load after the call to collaborator(), our answer affects whether

this unsafe code is legal.

The Tootsie Pop Model

Just for fun, let’s look at how this plays out in the Tootsie Pop

model (TPM). As I wrote before, whether this code is legal will

ultimately depend on whether patsy is located in an unsafe

context. The way I described the model, unsafe contexs are tied to

modules, so I’ll stick with that, but there might also be other ways

of defining what an unsafe context is.

First let’s imagine that all three functions are in the same module:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Here, because instigator and collaborator contain unsafe blocks,

the module foo is considered to be an unsafe context, and thus

patsy is also located within the unsafe context. This means that the

unsafe code would be legal and the optimization would not. This is

because the TPM does not allow us to trust types

within an unsafe

context.

However, it’s worth pointing out one other interesting

detail. Just because the TPM model does not authorize the

optimization, that doesn’t mean that it could not be performed. It

just means that to perform the optimization would require detailed

interprocedural alias analysis. That is, a highly optimizing compile

might analyze instigator, patsy, and collaborator and determine

whether or not the writes in collaborator can affect patsy (of

course here they can, but in more reasonable code they likely would

not). Put another way, the TPM basically tells you here are

optimizations you can do without doing anything sophisticated

; it

doesn’t put an upper limit on what you can do given sufficient extra

analysis.

OK, so now here is another recasting where the functions are spread between modules:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

In this case, the module bar does not contain unsafe blocks, and

hence it is not an unsafe context. That means that we can optimize

patsy. It also means that instigator is illegal:

1 2 3 | |

The problem here is that instigator is calling patsy, which is

defined in a safe context (and hence must also be a safe

function). That implies that instigator must fulfill all of Rust’s

basic permissions for the arguments that patsy expects. In this

case, the argument is a &usize, which means that the usize must be

accessible and immutable for the entire lifetime of the reference;

that lifetime encloses the call to patsy. And yet the data in

question can be mutated (by collaborator). So instigator is

failing to live up to its obligations.

TPM has interesting implications for the Rust optimizer. Basically,

whether or not a given statement can trust

the types of its

arguments ultimately depends on where it appeared in the original

source. This means we have to track some info when inlining unsafe

code into safe code (or else ‘taint’ the safe code in some way). This

is not unique to TPM, though: Similar capabilities seem to be required

for handling e.g. the C99 restrict keyword, and we’ll see that they

are also important when trusting types.

What if we fully trusted types everywhere?

Of course, the TPM has the downside that it hinders optimization in

unchecked-get use case. I’ve been pondering various ways to address

that. One thing that I find intuitively appealing is the idea of

trusting Rust types everywhere. For example, the idea might be that

whenever you create a shared reference like &usize, you must

ensure that its associated permissions hold. If we took this approach,

then we could perform the optimization on patsy, and we could say

that instigator is illegal, for the same reasons that it was illegal

under TPM when patsy was in a distinct module.

However, trusting types everywhere – even in unsafe code –

potentially interacts in a rather nasty way with lifetime inference.

Here is another example function to consider, alloc_free:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

What is happening here is that we allocate some memory containing an

integer, create a reference that refers to it, read from that

reference, and then free the original memory. We then use the value

that we read from the reference. The question is: can the compiler

copy-propagate

that read down to the call to use()?

If this were C code, the answer would pretty clearly be no (I

presume, anyway). The compiler would see that free(p) may invalidate

q and hence it act as a kind of barrier.

But if we were to go all in

on trusting Rust types, the answer would

be (at least currently) yes. Remember that the purpose of this

model is to let us do optimizations without doing fancy

analysis. Here what happens is that we create a reference q whose

lifetime will stretch from the point of creation until the end of its

scope:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | |

If this seems like a bad idea, it is. The idea that writing unsafe Rust code might be even more subtle than writing C seems like a non-starter to me. =)

Now, you might be tempted to think that this problem is an artifact of

how Rust lifetimes are currently tied to scoping. After all, q is

not used after the let r = *q statement, and if we adopted the

non-lexical lifetimes approach, that would mean the lifetime

would end there. But really this problem could still occur in a

NLL-based system, though you have to work a bit harder:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

Here the problem is that, from the compiler’s point of view, the

reference q is live at the point where we call free. This is

because it looks like we might need it to call use_again. But in

fact the programmer knows that condition1() and condition3() are

mutually exclusive, and so she may reason that the lifetime of q

ends earlier when condition1() holds than when it doesn’t.

So I think it seems clear from these examples that we can’t really fully trust types everywhere.

Trust types, not lifetimes?

I think that whatever guidelines we wind up with, we will not be able to fully trust lifetimes, at least not around unsafe code. We have to assume that memory may be invalidated early. Put another way, the validity of some unsafe code ought not to be determined by the results of lifetime inference, since mere mortals (including its authors) cannot always predict what it will do.

But there is a more subtle reason that we should not trust

lifetimes

. The Rust type system is a conservative analysis that

guarantees safety – but there are many notions of a reference’s

lifetime

that go beyond its capabilities. We saw this in the

previous section: today we have lexical lifetimes. Tomorrow we may

have non-lexical lifetimes. But humans can go beyond that and think

about conditional control-flow and other factors that the compiler is

not aware of. We should not expect humans to limit themselves to what

the Rust type system can express when writing unsafe code!

The idea here is that lifetimes are sometimes significant to the model – in particular, in safe code, the compiler’s lifetimes can be used to aid optimization. But in unsafe code, we are required to assume that the user gets to pick the lifetimes for each reference, but those choices must still be valid choices that would type check. I think that in practice this would roughly amount to “trust lifetimes in safe contexts, but not in unsafe contexts.

Impact of ignoring lifetimes altogether

This implies that the compiler will have to use the loads that the

user wrote to guide it. For example, you might imagine that the the

compiler can move a load from x down in the control-flow graph,

but only if it can see that x was going to be loaded anyway. So

if you consider this variant of alloc_free:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Here we can choose to either eliminate the first load (let r = *q)

or else replace use(*q) with use(r). Either is ok: we have

evidence that the user believes the lifetime of q to enclose

free. (The fact that it doesn’t is their fault.)

But now lets return to our patsy() function. Can we still optimize

that?

1 2 3 4 5 | |

If we are just ignoring the lifetime of v, then we can’t – at least

not on the basis of the type of v. For all we know, the user

considers the lifetime of v to end right after let l = *v. That’s

not so unreasonable as it might sound; after all, the code looks to

have been deliberately written to load *v early. And after all, we

are trying to enable more advanced notions of lifetimes than those

that the Rust type system supports today.

It’s interesting that if we inlined patsy into its caller, we might

learn new information about its arguments that lets us optimize more

aggressively. For example, imagine a (benevolent, this time) caller

like this:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

If we inlined patsy into kindly_fn, we get this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Here we can see that *x must be valid after collaborator(), and so

we can optimize the function as follows (we are moving the load of

*x down, and then applying CSE to eliminate the double load):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

There is a certain appeal to trust types, not lifetimes

, but

ultimately I think it is not living up to Rust’s potential: as you

can see above, we will still be fairly reliant on inlining to recover

needed context for optimizing. Given that the vast majority of Rust is

safe code, where these sorts of operations are harmless, this seems

like a shame.

Trust lifetimes only in safe code?

An alternative to the TPM is the

Asserting-Conflicting Access

model (ACA), which was proposed

by arielb1 and ubsan. I don’t claim to be precisely representing their

model here: I’m trying to (somewhat separately) work through those

rules and apply them formally. So what I write here is more inspired

by

those rules than reflective of it.

That caveat aside, the idea in their model is that lifetimes are

significant to the model, but you can’t trust the compiler’s inference

in unsafe code. There, we have to assume that the unsafe code author

is free to pick any valid lifetime, so long as it would still type

check (not borrow check

– i.e., it only has to ensure that no data

outlives its owning scope). Note the similarities to the Tootsie Pop

Model here – we still need to define what an unsafe context

is, and

when we enter such a context, the compiler will be less aggressive in

optimizing (though more aggressive than in the TPM). (This has

implications for the unchecked-get example.)

Nonetheless, I have concerns about this formulation because it seems

to assume that the logic for unsafe code can be expressed in terms

of Rust’s lifetimes – but as I wrote above Rust’s lifetimes are

really a conservative approximation. As we improve our type system,

they can change and become more precise – and users might have in

mind more precise and flow-dependent lifetimes still. In particular,

it seems like the ACA

would disallow my alloc_free2 example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

Intuitively, the problem is that the lifetime of q must enclose the

points (1), (2), (3), and (4) that are commented above. But the user

knows that condition1() and condition3() are mutually exclusive,

so in their mind, the lifetime ends either when we reach point (2),

since they know that this means that point (4) is unreachable.

In terms of their model, the conflicting access would be (2) and the asserting access would be (1). But I might be misunderstanding how this whole thing works.

Trust lifetimes at safe fn boundaries

Nonetheless, perhaps we can do something similar to the ACA model

and say that: we can trust lifetimes in safe code

but totally

disregard them in unsafe code

(however we define that). If we

adopted these definitions, would that allow us to optimize patsy()?

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Presuming patsy() is considered to be safe code

, then the answer is

yes. This in turn implies that any unsafe callers are obligated to

consider patsy() as a block box

in terms of what it might do with 'a.

This flows quite naturally from a permissions

perspective — giving

a reference to a safe fn implies giving it permission to use that

reference any time during its execution. I have been (separately)

trying to elaborate this notion, but it’ll have to wait for a separate post.

Conclusion

One takeaway from this meandering walk is that, if we want to make it easy to optimize Rust code aggressively, there is something special about the fn boundary. In retrospect, this is really not that surprising: we are trying to enable intraprocedural optimization, and hence the fn boundary is the boundary beyond which we cannot analyze – within the fn body we can see more.

Put another way, if we want to optimize patsy() without doing any

interprocedural analysis, it seems clear that we need the caller to

guarantee that v will be valid for the entire call to patsy:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

I think this is an interesting conclusion, even if I’m not quite sure where it leads yet.

Another takeaway is that we have to be very careful trusting lifetimes around unsafe code. Lifetimes of references are a tool designed for use by the borrow checker: we should not use them to limit the clever things that unsafe code authors can do.

Note on comments

Comments are closed on this post. Please post any questions or comments on the internals thread I’m about to start. =)

Also, I’m collecting unsafe-related posts into the unsafe category.

http://smallcultfollowing.com/babysteps/blog/2016/09/12/thoughts-on-trusting-types-and-unsafe-code/

|

|