Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Daniel Stenberg: HTTP Workshop 2015, day -1 |

I’ve traveled to a rainy and gray M"unster, Germany, today and checked in to my hotel for the coming week and the HTTP Workshop. Tomorrow is the first day and I’m looking forward to it probably a little too much.

I’ve traveled to a rainy and gray M"unster, Germany, today and checked in to my hotel for the coming week and the HTTP Workshop. Tomorrow is the first day and I’m looking forward to it probably a little too much.

There is a whole bunch of attendees coming. Simply put, most of the world’s best brains and the most eager implementers of the HTTP stacks that are in use today and will be in use tomorrow (with a bunch of notable absentees of course but you know you’ll be missed). I’m happy and thrilled to be able to take part during this coming week.

http://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2015/07/26/http-workshop-2015-day-1/

|

|

Julien Vehent: Using Mozilla Investigator (MIG) to detect unknown hosts |

MIG is a distributed forensics framework we built at Mozilla to keep an eye on our infrastructure. MIG can run investigations on thousands of servers very quickly, and focuses on providing low-level access to remote systems, without giving the investigator access to raw data.

As I was recently presenting MIG at the DFIR Summit in Austin, someone in the audience asked if it could be used to detect unknown or rogue systems inside a network. The best way to perform that kind of detection is to watch the network, particularly for outbound connections rogue hosts or malware would establish to a C&C server. But MIG can also help the detection by inspecting ARP tables of remote systems and cross-referencing the results with local mac addresses on known systems. Any MAC address not configured on a known system is potentially a rogue agent.

First, we want to retrieve all the MAC addresses from the ARP tables of known systems. The netstat module can perform this task by looking for neighbor MACs that match regex "^[0-9a-f]", which will match anything hexadecimal.

$ mig netstat -nm "^[0-9a-f]" > /tmp/seenmacs

We store the results in /tmp/seenmacs and pull a list of unique MACs using some bash.

$ awk '{print tolower($5)}' /tmp/seenmacs | sort | uniq

00:08:00:85:0b:c2

00:0a:9c:50:b4:36

00:0a:9c:50:bc:61

00:0c:29:41:90:fb

00:0c:29:a7:41:f7

00:10:db:ff:10:00

00:10:db:ff:30:00

00:10:db:ff:f0:00

00:21:53:12:42:c1

We now want to check that every single one of the seen MAC addresses is configured on a known agent. Again, the netstat module can be used for this task, this time by querying local mac addresses with the -lm flag.

Now the list of MACs may be quite long, so instead of running one MIG query per MAC, we group them 50 by 50 using the following script:

#! /usr/bin/env bash

i=50

input=$1

output=$2

while true

do

echo -n "mig netstat " >> $output

for mac in $(awk '{print tolower($5)}' $1|sort|uniq|head -$i|tail -50)

do

echo -n "-lm $mac " >> $output

done

echo >> $output

i=$((i+50))

if [ $i -gt $(awk '{print tolower($5)}' $1|sort|uniq|wc -l) ]

then

exit 0

fi

done

The script will build MIG netstat command with 50 arguments max. Invoke it with /tmp/seenmacs as argument 1, and an output file as argument 2.

$ bash /tmp/makemigmac.sh /tmp/seenmacs /tmp/migsearchmacs

/tmp/migsearchmacs now contains a number of MIG netstat commands that will search seen MAC addresses across the configured interfaces of known hosts. Run the commands and pipe the output to a results file.

$ for migcmd $(cat /tmp/migsearchmacs); do $migcmd >> /tmp/migfoundmacs; done

We now have a file with seen MAC addresses, and another one with MAC addresses configured on known systems. Doing the delta of the two is fairly easy in bash:

$ for seenmac in $(awk '{print tolower($5)}' /tmp/seenmacs|sort|uniq); do

hasseen=""; hasseen=$(grep $seenmac /tmp/migfoundmacs)

if [ "$hasseen" == "" ]; then

echo "$seenmac is not accounted for"

fi

done

00:21:59:96:75:7f is not accounted for

00:21:59:98:d5:bf is not accounted for

00:21:59:9c:c0:bf is not accounted for

00:21:59:9e:3c:3f is not accounted for

00:22:64:0e:72:71 is not accounted for

00:23:47:ca:f7:40 is not accounted for

00:25:61:d2:1b:c0 is not accounted for

00:25:b4:1c:c8:1d is not accounted forAutomating the detection

It's probably a good idea to run this procedure on a regular basis. The script below will automate the steps and produce a report you can easily email to your favorite security team.

#!/usr/bin/env bash

SEENMACS=$(mktemp)

SEARCHMACS=$(mktemp)

FOUNDMACS=$(mktemp)

echo "seen mac addresses are in $SEENMACS"

echo "search commands are in $SEARCHMACS"

echo "found mac addresses are in $FOUNDMACS"

echo "step 1: obtain all seen MAC addresses"

$(which mig) netstat -nm "^[0-9a-f]" 2>/dev/null | grep 'found neighbor mac' | awk '{print tolower($5)}' | sort | uniq > $SEENMACS

MACCOUNT=$(wc -l $SEENMACS | awk '{print $1}')

echo "$MACCOUNT MAC addresses found"

echo "step 2: build MIG commands to search for seen MAC addresses"

i=50

while true;

do

echo -n "$i.."

echo -n "$(which mig) netstat -e 50s " >> $SEARCHMACS

for mac in $(cat $SEENMACS | head -$i | tail -50)

do

echo -n "-lm $mac " >> $SEARCHMACS

done

echo -n " >> $FOUNDMACS" >> $SEARCHMACS

if [ $i -gt $MACCOUNT ]

then

break

fi

echo " 2>/dev/null &" >> $SEARCHMACS

i=$((i+50))

done

echo

echo "step 3: search for MAC addresses configured on local interfaces"

bash $SEARCHMACS

sleep 60

echo "step 4: list unknown MAC addresses"

for seenmac in $(cat $SEENMACS)

do

hasseen=$(grep "found local mac $seenmac" $FOUNDMACS)

if [ "$hasseen" == "" ]; then

echo "$seenmac is not accounted for"

fi

done

The list of unknown MACs can then be used to investigate the endpoints. They could be switches, routers or other network devices that don't run the MIG agent. Or they could be rogue endpoints that you should keep an eye on.

Happy hunting!

|

|

Panos Astithas: Lessons from Startup Weekend |

I had an exhausting but fun weekend at the Athens Startup Weekend a few days ago. Along with Christos I joined Yannis, Panagiotis Christakos and Babis Makrinikolas on the Newspeek project. When Yannis pitched the idea on Friday night, the main concept was to create a mobile phone application that would provide a better way to view news on the go. I don't believe it was very clear in his mind then, what would constitute a "better" experience, but after some chatting about it we all defined a few key aspects, which we refined later with lots of useful feedback and help from George. Surprisingly, for me at least, in only two days we managed to design, build and present a working prototype in front of the judges and the other teams. And even though the demo wasn't exactly on par with our accomplishments, I'm still amazed at what can be created in such a short time frame.

I had an exhausting but fun weekend at the Athens Startup Weekend a few days ago. Along with Christos I joined Yannis, Panagiotis Christakos and Babis Makrinikolas on the Newspeek project. When Yannis pitched the idea on Friday night, the main concept was to create a mobile phone application that would provide a better way to view news on the go. I don't believe it was very clear in his mind then, what would constitute a "better" experience, but after some chatting about it we all defined a few key aspects, which we refined later with lots of useful feedback and help from George. Surprisingly, for me at least, in only two days we managed to design, build and present a working prototype in front of the judges and the other teams. And even though the demo wasn't exactly on par with our accomplishments, I'm still amazed at what can be created in such a short time frame.

- If you plan to win, work on the business aspect, not on the technology. Personally, I didn't go to ASW with plans to create a startup, so I didn't care that much about winning. I mostly considered the event as a hackathon, and tried my best to end up with a working prototype. Other teams focused more on the business side of things, which is understandable, given the prize. Investors fund teams that have a good chance to return a profit, not the ones with cool technology and (mostly) working demos. Still, the small number of actual working prototypes was a disappointment for me. Even though the developers were the majority in the event, you obviously can't have too many of them in a Startup Weekend.

- For quick server-side prototyping and hosting, Google App Engine is your friend. Since everyone in the team had Java experience, we could have gone with a JavaEE solution and set up a dedicated server to host the site. But, since I've always wanted to try App Engine for Java and the service architecture mapped nicely to it, we tried a short experiment to see if it could fly. We built a stub service in just a few minutes, so we decided it was well worth it. Building our RESTful service was really fast, scalability was never a concern and the deployment solution was a godsend, since the hosting service provided for free by the event sponsors was evidently overloaded. We're definitely going to use it again for other projects.

- jQTouch rocks! Since our main deliverable would be an iPhone application, and there were only two of us who had ever built an iPhone application (of the Hello World variety), we knew we had a problem. Fortunately, I had followed the jQTouch development from a reasonable distance and had witnessed the good things people had to say, so I pitched the idea of a web application to the team and it was well received. iPhone applications built with web technologies and jQTouch can be almost indistinguishable from native ones. We all had some experience in building web applications, so the prospect of having a working prototype in only two days seemed within the realm of possibility again. The future option of packaging the application with PhoneGap and selling it in the App Store was also a bonus point for our modest business plan.

- For ad-hoc collaboration, Mercurial wins. Without time to set up central repositories, a DVCS was the obvious choice, and Mercurial has both bundles and a standalone server that make collaborative coding a breeze. If we had zeroconf/bonjour set up in all of our laptops, we would have used the zeroconf extension for dead easy machine lookup, but even without it things worked flawlessly.

- You can write code with a netbook. Since I haven't owned a laptop for the last three years, my only portable computer is an Asus EEE PC 901 running Linux. Its original purpose was to allow me to browse the web from the comfort of my couch. Lately however, I'm finding myself using it to write software more than anything else. During the Startup Weekend it had constantly open Eclipse (for server-side code), Firefox (for JavaScript debugging), Chrome (for webkit rendering), gedit (for client-side code) and a terminal, without breaking a sweat.

- When demoing an iPhone application, whatever you do, don't sweat. Half-way through our presentation, tapping the buttons didn't work reliably all the time, so anxiety ensued. Since we couldn't make a proper presentation due to a missing cable, we opted for a live demo, wherein Yannis held the mic and made the presentation, and I posed as the bimbo that holds the product and clicks around. After a while we ended up both touching the screen, trying to make the bloody buttons click, which ensured the opposite effect. In retrospect, using a cloth occasionally would have made for a smoother demo, plus we could have slipped a joke in there, to keep the spirit up.

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/PastMidnight/~3/oPE_mDZ520U/lessons-from-startup-weekend.html

|

|

Matthew Noorenberghe: Firefox Password Manager Update: 2015-Q1 |

- Telemetry – Probes (with the prefix PWMGR_) were added to gain a better understanding of how users were using the feature and to allow measuring the impact of improvements.

- Ignoring @autocomplete=off in login forms – An autocomplete attribute with a value of "off" no longer disables auto-filling of login fields. This puts users back in control of their login experience and aligns with the direction of other browser vendors. Last year we started ignoring @autocomplete=off when deciding whether to ask the user to save/update their login so this is an evolution of that change. Note that @autocomplete=off is still effective outside login forms e.g. to implement custom search box autocompletion.

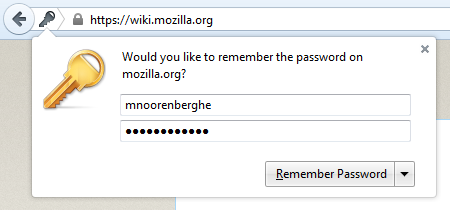

- Capture doorhanger fields – The remember/update password doorhanger notification is now easier to visually scan with fields for the captured username and password. The username field is also editable which helps in cases where the detected username is incorrect or missing.

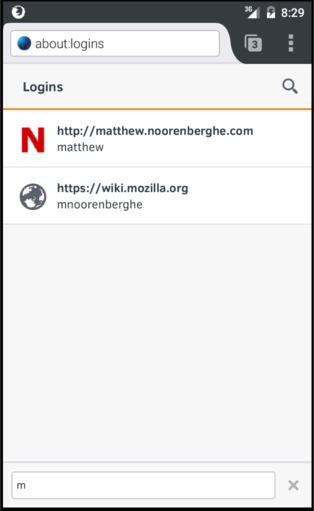

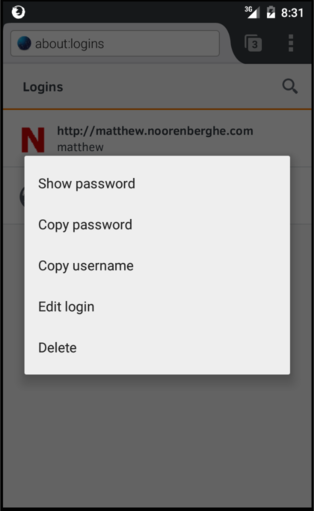

- Viewing and managing logins on Android – A password management interface (about:logins) was added to Firefox for Android and is accessible via the menu under Tools > Logins.

- Per-site recipes – A new mechanism was added to allow per-site overrides to the password manager capture and fill heuristics since it's not feasible/scalable to have general ones which work for every website. Initial recipe support allows overriding the username and password field detection via CSS selectors. There are only a handful of recipes currently in use as there hasn't been much focus/communication on gathering these yet but you're encouraged to file bugs about sites that don't work with the password manager (and if you're ambitious you can even submit patches to the JSON file).

- Android Capture Doorhanger Polish – Capture doorhanger visuals were polished in preparation for later improvements.

- General bug fixes – As usual, there were bug fixes for functionality that simply didn't work as expected. For example, Bug 1121040 regarding forms submitting via the Enter key during username autocompletion before a password had time to be filled in the password field.

http://matthew.noorenberghe.com/blog/2015/07/firefox-password-manager-update-2015-Q1

|

|

Tantek Celik: Dark Forest Run |

Yesterday morning I ran through a forest in pitch darkness for the first time. I had a headlamp, a general sense of direction (uphill), and the knowledge that friends were just out of sight up ahead.

When I left my house it was dark as night in the city, which really means never darker than the dim glow from diffuse streetlamps and other light polluters. I ran nearly a kilometer before meeting my fellow #nopasoparungang members at the intersection of Frederick & Stanyan streets.

From there we ran half a mile up Stanyan’s steepest segments (240 feet elevation) to Belgrave Ave and the eastern edge of the Mt Sutro Open Space Preserve. Undaunted by poison oak warning signs, we leapt onto the narrow dirt forest trail. In mere seconds we disappeared into the dense woods, the city glow faded, and our headlamps barely lit the trail ahead. Anything beyond 10 meters was nothing but gray shapes blending into darkness.

Our gang of four split into lead and tail pairs, and we soon lost sight of the lead headlamps. We didn’t bother navigating by mobile, even the dimmest of backlighting would have been blinding. Whenever the trail split, we chose the uphill path.

Not only was the forest darkness pierced only by our headlamps, it was silent except for the sounds we made, breathing, pounding the trail, rustling leaves, snapping twigs.

The lead pair rejoined us from behind, having taken a wrong turn and doubled back. We emerged from the south side of the forest onto the street and found the few other @Nov_Project_SF early gang arrivals who took our photo.

Now seven strong, we hiked up Johnstone drive just a bit and ran uphill onto the East Ridge Trail, again leaving civilization behind in just moments. We ran all the way up to the Mt. Sutro summit, to a clearing formerly used for Nike Missile Control Site SF-89C.

Looking back through the dark forest I could see dawn’s light in the East.

From Fredrick & Stanyan we had only run a mile, and yet the second half of it through pitch black woods, and 400 more feet of incline for total of 640 feet of elevation gain.

Tapering for this weekend's race, once I reached the summit I did reps of planking, tricep dips, pushups, all while swatting perhaps nearly 100 mosquitos. Everyone else ran up & down the ridge trail and others nearby. A few more runners found us during the 30 minute hills workout.

Afterwards we ran back down to the meeting point on the street, and hugged the 6:25am arrivals. Then we did it all again, this time in the sunrise lit trails below.

This is November Project San Francisco #hillsforbreakfast. We run through poison-ivy laden mosquito-infested forests from darkness through dawn and into the sunrise.

Why are we shushing with our fingers? We heard from a concerned hiker that "the sound travels really far" out of the forest (which is odd, because the sound from the city doesn’t seem to make it into the forest). For more, see: NPSF: Do you know what it feels like to be 90 years old?

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: Updating you on 38 just-in-time |

- The Faceblech bug with the new IonPower JavaScript JIT compiler is squashed, I think, after repairing some conformance test failures which in turn appear to have repaired Forceblah. In my defence, the two bugs in question were incredibly weird edge cases and these tests are not part of the usual JIT test suite, so I guess we'll have to run them as well in future. This also repairs an issue with Instagrump which is probably the same underlying issue since Faceboink owns them also.

The silver lining after all that was that I was considering disabling inlining in the JIT prior to release, which worked around the "badness," but also cut the engine speed in about half. (Still faster than JaegerMonkey!) To make this a bit less of a hit, I tuned the thresholds for starting the twin JITs and got about 10% improvement without inlining. With inlining back on, it's still faster by about 4% and change -- the G5 now achieves a score of nearly 5800 on V8, up from 5560. I also tweaked our foreground finalization patch for generational GC so that we should be able to get the best of both worlds. Overall you should see even better performance out of this next beta.

- I have a presumptive fix for the webfont "ATSUI puke" on the New York Times, but it's not implemented or well-tested yet. This is a crash on 10.5, so I consider it a showstopper and it will be fixed before the next beta. (It affects 31.8 also but I will not be making another 31 release unless there is a Mozilla ESR chemspill.)

- The modified strip7 tool required for building 38.x has a serious bug in it that causes it to crash trying to strip certain symbols. I have fixed this bug and builders will need to install this new version (remember: do not replace your normal strip with this one; it is intentionally loose with the Mach-O specification). I will be uploading it sometime this week along with an updated gdb7 that has better debugger performance and repairs a bug with too eagerly disabling register display while single-stepping Ion code.

- I can confirm saved passwords do not appear in the preferences panel. They do work, though, and can be saved, so this is more of an issue with managing them; while it's possible to do so manually it requires some inconvenient screwing around with your profile, so I consider this the highest priority of the non-showstopper bugs.

- Checkboxes on the dropdown menus from the Console tabs do not appear. This specific manifestation is purely cosmetic because they work normally otherwise, but this may be an indication there is a similar issue with dropdowns and context menus elsewhere, so I do want to fix this as well.

The localizer elves have French, German, Spanish, Italian, Russian and Finnish installers available. Our Japanese localization appears to have dropped off the web, so if you can help us, o-negai shimasu! Swedish just needs a couple of strings to be finished. We do not yet have Polish or Asturian, which we used to, so if you can help on any of these languages, please visit issue 42 where Chris is coordinating these efforts. A big thank you to all of our localizers!

Once the localizations are all in, the Google Code project will be frozen to prepare for the wiki and issue tracker moving to Github ahead of Google Code going read-only on 24 August. Downloads will remain on SourceForge, but everything else will go to Github, including the source tree when we eventually drop source parity. I was hoping to have an Elcapitanspoof up in time for 38's final release, but we'll see if I have time to do the graphics.

Watch for the next beta to come out by next weekend with any luck, which gives us enough time if there needs to be a third emergency release prior to the final (weekend prior to 11 August).

Finally, I am pleased to note we are now no longer the only PowerPC JavaScript JIT out there, though we are the only one I know of for Mozilla SpiderMonkey. IBM has been working on a port of Google V8 to PowerPC for some time, both AIX and Linux, which recently became an official part of the Google V8 repository (i.e., the PPC port is now officially supported). If you've been looking at nabbing a POWER8 with that money burning a hole in your pocket, it even works with the new Power ISA little endian mode, of which we dare not speak. Since uppsala, Floodgap's main server, is a POWER6 running AIX and should be able to run this, I might give it a spin sometime when I have a few spare cycles. However, before some of the freaks amongst you get excited and think this means Google Chrome on OS X/ppc is just around the corner, there's still an awful lot more work required to get it operational than just the JavaScript engine, and it won't be me that works on it. It does mean, however, that things like node.js will now work on a Power-based server with substantially less fiddling around, and that might be very helpful for those of you who run Power boxes like me.

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2015/07/updating-you-on-38-just-in-time.html

|

|

Hannah Kane: Quick update: engagement on the MLN Site |

Pledge to Teach

In my last post, I mentioned that we had recently launched the Pledge to Teach the Web. Since we launched it three weeks ago, 240 people have taken the pledge.

Of those who’ve taken the pledge, about a quarter of them have also completed a survey that we sent as a follow-up. The survey is helping us gain a better understanding of our audience, their contexts for teaching, and their needs. We’ll share an analysis of the survey results next month.

Of those who’ve taken the pledge, about a quarter of them have also completed a survey that we sent as a follow-up. The survey is helping us gain a better understanding of our audience, their contexts for teaching, and their needs. We’ll share an analysis of the survey results next month.

Site Traffic

Since we launched teach.mozilla.org back in April, we haven’t been particularly focused on driving traffic to the site. That changed recently, as we began our Maker Party promotion efforts in earnest. We started promoting Maker Party on both beta.webmaker.org and on mozilla.org. Those two referrals, along with our email campaign, led to our most highly trafficked week on the site since launch, during the lead-up to Maker Party. Our highest day was July 13th, when we had over 11K sessions. Since the initial bump, traffic has dropped back down again to between 1200 and 2500 sessions per day.

Unsurprisingly, the Maker Party page is the most popular content, after the homepage. The Activities page is the next most popular.

What we’re doing next with regard to user engagement

- Adding analytics tracking to several things so we can better measure conversion rates.

- Experimenting on pledge flow to increase conversion rate. One possibility is to make the pledge the only CTA on the homepage.

- Determining our post-Maker Party strategy for people who take the pledge. We’re discussing ideas here.

- Experimenting with “Community” link to increase Discourse activity. This is a larger-than-the-site effort , though. We can be promoting Discourse across all of our work.

http://hannahgrams.com/2015/07/24/quick-update-engagement-on-the-mln-site/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Webmaker Demos July 24 2015 |

Webmaker Demos July 24 2015

Webmaker Demos July 24 2015

|

|

Support.Mozilla.Org: What’s up with SUMO – 24th July |

A warm “hello” to all our readers across SUMO and Planet Mozilla! Here we go with another round of the good, the bad, and the reminders… ;-)

Say “hello” to the newcomers!

Contributors of the week

Last Monday SUMO Community meeting

Reminder: the next SUMO Community meeting…

- …is going to take place on Monday, 27th of July. Join us!

- If you want to add a discussion topic to upcoming the live meeting agenda:

- Start a thread in the Community Forums, so that everyone in the community can see what will be discussed and voice their opinion here before Monday (this will make it easier to have an efficient meeting).

- Please do so as soon as you can before the meeting, so that people have time to read, think, and reply (and also add it to the agenda).

Help needed – thank you!

- Help us record an awesome SUMO video! More details here.

- Help us make things happen after the #mozwww Whistler meetup – go to this thread and read more about the sessions linked from there – and provide feedback!

- Let us know what you think should be the theme for the upcoming SUMO KB Day (in two weeks)

- Send Firefox 39 and Firefox 40 bugs to Mark.

Let’s work together on the script for the tutorial videos for SUMO l10n

- ! Use the “comments” feature to leave your feedback and ideas in the document.

Developers

- The notes from the most recent Platform meeting can be found here.

- The video is on our YouTube channel as well.

- The next Platform meeting will take place on the 30th of July.

Community

- Reminder: Maker Party 2015 is here! The fourth annual celebration of making and learning on the Web has started and runs until Friday, July 31. Join the rest of the world!

- Happy 10th anniversary, MDN!

Support Forum

- Say “hello” to the awesome, hyperactive forum helpers!

- Reminder: the One and Done SUMO Contributor Support Training is live. Start here!

Knowledge Base

- What do you think about this locale-free screenshot for FxOS? Let us know in the forums.

L10n

- Say “hello” to the amazing, superactive localizers (aka SUMO l10ns)!

Firefox

- The Windows 10 update is coming next week! (July 29th)

- Setting firefox as a default browser there doesn’t seem that straightforward – read about it here.

- We have an article about this in the works – stay tuned!

- Firefox for Win64 will officially release with Firefox 40

- Add-on signing: Firefox 40 will warn users, but not block add-ons

- Built-in Tracking Protection is coming to Firefox!

- Reminder: If you need more information about Adobe Flash and Firefox, visit this thread.

Firefox OS

Thunderbird

- Reminder: as of July 1st, Thunderbird is 100% Community powered and owned! You can still +needinfo Roland in Bugzilla or email him if you need his help as a consultant. He will also hang around in #tb-support-crew.

Don’t forget that we are on Twitter! And don’t forget to cool off in the heat of the cruel summer (if you happen to have one, that is). See you on Monday!

https://blog.mozilla.org/sumo/2015/07/24/whats-up-with-sumo-24th-july/

|

|

Mozilla Reps Community: Reps Weekly Call – July 23th 2015 |

Last Thursday we had our weekly call about the Reps program, where we talk about what’s going on in the program and what Reps have been doing during the last week.

Summary

- Firefox OS Foxfooding.

- Featured events.

- Webmaker app launch in Indonesia.

AirMozilla video

Detailed notes

Shoutouts to Ahmed Nefzaoui and Yofie Setiawan (@yofiesetiawan) as the Reps of the Month!

Firefox OS Foxfooding

The Foxfooding program started as an employee initiative but it will be expanded to mozillians soon.

A good way to contribute now is check the Foxfooding dashboard and help to triage bugs, we also have an app (Triagr) to help with this login with your bugzilla user, you can install or try it. Feel free to follow @foxfooding on Twitter.

Discourse topic about Foxfooding.

There is also the B2gdroid initiative to be able to experience Gaia directly on an Android device.

Future for Firefox OS is very interesting, like NGA (New Gaia Architecture) and new features like stream apps, share apps, hack apps, share modifications (Hackerspace).

Featured events

- Maker Party Events:

- Kathmandu (Nepal), 25th. Rep: Surit Aryal

- Stockholm (Sweden), 25th. Rep: Ake Nygren

- Kanpur (India), 28th. Rep: Chandan Kumar Baba

- Sertaozinho (Brazil), 29th. Rep: Sergio Oliveira

- And many more events in: https://events.webmaker.org/events

- HackDehli – New Dehli (India). 25th-26th.

- Mozilla Hindi Community Meetup – New Dehli (India). 25th-26th

- Firefox OS Launch week 6 in Mauritius – 25 July 2015 in the South of Mauritius at Mahebourg.

Webmaker app launch in Indonesia

The launch is going to happen in August with the training help of WilliamQ, Bobby, Paul, Kevin.

The preparation is still in progress, including localization, planning for events content.

Don’t forget to comment about this call on Discourse and we hope to see you next week!

https://blog.mozilla.org/mozillareps/2015/07/24/reps-weekly-call-july-23th-2015/

|

|

Alex Vincent: Introducing a WebGL-DOM Visualization Tool |

Repository: https://bitbucket.org/verbosio/webgl-dom

Home page: https://alexvincent.us/webgl-dom/

tl;dr: I have a new way of visualizing DOM trees in WebGL, and I’m looking for volunteers to improve the basic tool, especially on the WebGL side with three.js.

I’ve run into some trouble with an experimental Document Object Model. Specifically, I’m trying to visualize it, but I’m dealing with multiple dimensions:

- The parent-child node relationships

- Sibling nodes

- Attributes of DOM Element nodes

- Atomic change sets

- and at least two models of “shadow content”.

About four to six weeks ago, I realized I needed a tool to not only debug the DOM I’m trying to build, but to simulate new ideas that I haven’t yet implemented. So I started building a WebGL-based visualization tool.

The tool currently has two main tasks:

- Transforming a XML document into a specific JSON format

- Generating a tree diagram in WebGL from JSON documents in the specified format

Most importantly, hand-editing this JSON should allow me to show ideas that currently cannot be done in the standard DOM. The “WebGL Inspector sample” link from the home page shows this: it takes only JSON as input and renders the tree.

It is very primitive right now, a mere starting point. I’m posting this now, hoping to find a volunteer who’s more familiar with WebGL / three.js than I am to improve on the rendering parts. The image is static: there’s no zoom, pan, or rotation support whatsoever. I really would like some help there.

Also, it doesn’t work in Google Chrome, but that’s because I had to specify type=”application/javascript;version=1.8” to make it work in Mozilla Firefox 39+. (I like ECMAScript 6th edition and strict mode, thank you very much. I just wish it worked without versioning. I understand that’s Coming Soon.)

There is some click support: clicking on a sphere should give details about the corresponding DOM Node, including the nodeName and nodeType.

If anyone out there likes the 3-D visualization idea and wants to reimplement it in the Firefox Developer Tools, be my guest. Though the Tilt add-on for Firefox is more practical right now.

|

|

Nick Desaulniers: Additional C/C++ Tooling |

21st Century C by Ben Klemens was a great read. It had a section with an intro to autotools, git, and gdb. There are a few other useful tools that came to mind that I’ve used when working with C and C++ codebases. These tools are a great way to start contributing to Open Source C & C++ codebases; running these tools on the code or adding them to the codebases. A lot of these favor command line, open source utilities. See how many you are familiar with!

Build Tools

CMake

The first tool I’d like to take a look at is CMake. CMake is yet another build tool; I realize how contentious it is to even discuss one of the many. From my experience working with Emscripten, we recommend the use of CMake for people writing portable C/C++ programs. CMake is able to emit Makefiles for unixes, project files for Xcode on OSX, and project files for Visual Studio on Windows. There are also a few other “generators” that you can use.

I’ve been really impressed with CMake’s modules for finding dependencies and another for fetching and building external dependencies. I think C++ needs a package manager badly, and I think CMake would be a solid foundation for one.

The syntax isn’t the greatest, but when I wanted to try to build one of my C++ projects on Windows which I know nothing about developing on, I was able to install CMake and Visual Studio and get my project building. If you can build your code on one platform, it will usually build on the others.

If you’re not worried about writing cross platform C/C++, maybe CMake is not worth the effort, but I find it useful. I wrestle with the syntax sometimes, but documentation is not bad and it’s something you deal with early on in the development of a project and hopefully never have to touch again (how I wish that were true).

Code Formatters

ClangFormat

Another contentious point of concern amongst developers is code style. Big companies with lots of C++ code have documents explaining their stylistic choices. Don’t waste another hour of your life arguing about something that really doesn’t matter. ClangFormat will help you codify your style and format your code for you to match the style. Simply write the code however you want, and run the formatter on it before commiting it.

It can also emit a .clang-format file that you can commit and clang-format will automatically look for that file and use the rules codified there.

Linters

Flint / Flint++

Flint is a C++ linter in use at Facebook. Since it moved from being implemented in C++ to D, I’ve had issues building it. I’ve had better luck with a fork that’s pure C++ without any of the third party dependencies Flint originally had, called Flint++. While not quite full-on static analyzers, both can be used for finding potential issues in your code ahead of time. Linters can look at individual files in isolation; you don’t have to wait for long recompiles like you would with a static analyzer.

Static Analyzers

Scan-build

Scan-build is a static analyzer for C and C++ code. You build your code “through” it, then use the sibling tool scan-view to see the results. Scan-view will emit and open an html file that shows a list of the errors it detected. It will insert hyperlinks into the resulting document that step you through how certain conditions could lead to a null pointer dereference, for example. You can also save and share those html files with others in the project. Static analyzers will help you catch bugs at compile time before you run the code.

Runtime Sanitizers

ASan and UBSan

Clang’s Address (ASan) and Undefined Behavior (UBSan) sanitizers are simply compiler flags that can be used to detect errors at runtime. ASan and UBSan two of the more popular tools, but there are actually a ton and more being implemented. See the list here. These sanitizers will catch bugs at runtime, so you’ll have to run the code to notice any violations, at variable runtime performance costs per sanitizer. ASan and TSan (Thread Sanitizer) made it into gcc4.8 and UBSan is in gcc4.9.

Header Analysis

Include What You Use

Include What You Use

(IWYU) helps you find unused or unnecessary #include preprocessor directives.

It should be obvious how this can help improve compile times. IWYU can also

help cut down on recompiles by recommending forward declarations under certain

conditions.

I look forward to the C++ module proposal being adopted, but until then this

tool can help you spot cruft that can be removed.

Rapid Recompiles

ccache

ccache greatly improves recompile times by caching the results of parts of the compilation process. I use when building Firefox, and it saves a great deal of time.

distcc

distcc is a distributed build system. Some folks at Mozilla speed up their Firefox builds with it.

Memory Leak Detectors

Valgrind

Valgrind has a suite of tools, my favorite being memcheck for finding memory leaks. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to work on OSX since 10.10. This page referring to ASan seems to indicate that it can do everything Valgrind’s Memcheck can, at less of a runtime performance cost, but I’m not sure how true this is exactly.

leaks

A much more primitive tool for finding leaks from the command line, BSD’s have

leaks.

1 2 3 | |

Profilers

Perf

Perf, and Brendan Gregg’s tools for emitting SVG flamegraphs from the output are helpful for finding where time is spent in a program. In fact, there are numerous perfomance analysis tools that are Linux specific. My recommendation is spend some time on Brendan Gregg’s blog.

DTrace

OSX doesn’t have the same tooling as Linux, but DTrace was ported to it. I’ve used it to find sampling profiles of my code before. Again, Brendan Gregg’s blog is a good resource; there are some fantastic DTrace one liners.

Debuggers

lldb

lldb is analogous to gdb. I can’t say I have enough experience with LLDB and GDB to note the difference between the two, but LLDB did show the relative statements forward and back from the current statement by default. I’m informed by my friends/mortal enemies using emacs that this is less of an issue when using emacs/gdb in combination.

Fuzzers

American Fuzzy Lop

American Fuzzy Lop (AFL) is a neat program that performs fuzzing on programs that take inputs from files and repeatedly runs the program, modifies the input trying to get full code coverage, and tries to find crashes. It’s been getting lots of attention lately, and while I haven’t used it myself yet, it seems like a very powerful tool. Mozilla employs the use of fuzzers on their JavaScript engine, for instance (not AFL, but one developed in house).

Disassemblers

gobjdump

If you really need to make sure the higher level code you’re writing is getting

translated into the assembly your expecting, gobjdump -S will intermix the

emitted binary’s disassembled assembly and the source code. This was used

extensively while developing my Brainfuck JIT.

Conclusion

Hopefully you learned of some useful tools that you should know about when working with C or C++. What did I miss?

http://nickdesaulniers.github.io/blog/2015/07/23/additional-c-slash-c-plus-plus-tooling/

|

|

Mike Hommey: Firefox nightlies for Linux are now using Gtk+3 |

As of last nightly (2015-07-23), Firefox for Linux is using Gtk+3 instead of Gtk+2.

Thanks to the recent efforts of Andrew Comminos, all remaining test failures are gone and mozilla-central now defaults to Gtk+3 builds. Some jobs on treeherder are still not converted, but this will come soon (bug 1186748).

If you’ve been using elm builds for dogfooding, you should be automatically switched to standard nightlies today or tomorrow. The elm branch will be recycled to do Gtk+2 builds so that they keep working. Those builds won’t be auto-updating, so don’t use them.

|

|

Joel Maher: lost in data – episode 1, tackling a bunch of alerts |

Today I recorded a session of me investigating talos alerts, It is ~35 minutes, sort of long, but doable in the background whilst grabbing breakfast or lunch!

I am looking forward to more sessions and answering questions that come up.

https://elvis314.wordpress.com/2015/07/23/lost-in-data-episode-1-tackling-a-bunch-of-alerts/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Lost in Data with Joel Maher - Episode 1 |

Taking a stab at the incoming alerts

Taking a stab at the incoming alerts

https://air.mozilla.org/lost-in-data-with-joel-maher-episode-1/

|

|

David Burns: Microsoft ship a WebDriver implementation |

Microsoft, the people still claim to be evil (who are actually big proponents of the the The Open Web), have... (wait for it...) SHIPPED. AN. IMPLEMENTATION. OF. WEBDRIVER!

At GTAC in California in 2011, Simon Stewart and I discussed that the Selenium project was at a crossroads (I am pretty sure beer was involved). We could ,and should, move this to the browser vendors. We had seen how in April the Chrome team had shipped their implementation and the Selenium project then deleted its implementation. I am pretty sure Daniel (Wagner-Hall) was glad to see it go.

In that time to now we have seen Mozilla get Marionette into Firefox and into release branches since Firefox 24 while slowly working on it (as well as Firefox OS support). We have seen Blackberry ship a version for the browser on their devices. We have seen mobile implementation with iOS-Driver, Selendroid and Appium.

The Spec is on track to be put forward for Recommendation by the end of the year. All the dreams that we (the Selenium Development team (my BFFs)) had are slowly coming true. This ship might be slow moving but it's mostly because some companies haven't always seen the value.

so...

.@kylealden I raise a drink to the @MSEdgeDev team (esp @thejohnjansen) for helping make this happen @jimevansmusic pic.twitter.com/eBxdpNNqPC

— David Burns (@AutomatedTester) July 23, 2015P.s. There is an open bug on the WebKit tracker for Safari support (and it is getting some internal push so I am hopeful!)

http://www.theautomatedtester.co.uk/blog/2015/microsoft-ship-a-webdriver-implementation.html

|

|

About:Community: Ten years of evolution of MDN |

![]() This week marks the tenth anniversary of Mozilla Developer Network (MDN) as a wiki. This post offers a deep dive into where MDN came from, how it has evolved in various ways, and where it may be going.

This week marks the tenth anniversary of Mozilla Developer Network (MDN) as a wiki. This post offers a deep dive into where MDN came from, how it has evolved in various ways, and where it may be going.

(This post is based in large part on a round table discussion about MDN that was held during the “Hack on MDN” weekend in Berlin in April 2015, and on Florian Scholz’s history of MDN’s JavaScript documentation.)

- What is MDN today?

- Who is MDN for?

- Beginnings of MDN

- Platform evolution

- Community evolution

- Branding evolution

- Content evolution

- MDN today and tomorrow

- MDN in 10 years?

What is MDN today?

For many web developers, MDN is the reference manual for the Web, the place they go to look up or learn about open web technologies. MDN offers much more than that. It is a resource for learning about the Web, and a place for developers to share their skills and knowledge. MDN’s strength lies in its openness, where anybody can help make the resources incrementally better, or substantially better. MDN can also encourage the growth of web technologies into new spaces from where they’ve been in the past.

MDN is a community of programmers, writers, and localizers. A few of these are paid staff of Mozilla, but they are a subset of the larger community of people who make small or large contributions.

One of the coolest things for those who contribute to MDN is that every time we talk to developers, they tell us how much they love MDN. It’s not, “Oh MDN is kind of cool,” or “It’s great.” The response is: “I love MDN. It’s the best resource out there.” It’s tremendously gratifying to feel that you are part of something that people really love.

Who is MDN for?

MDN serves a variety of audiences:

- Web developers, first and foremost

- People who want to teach themselves about web development

- Teachers of web development skills and concepts

- Developers in the ecosystem of Mozilla products, such as Firefox add-ons, and Firefox OS apps

- Developers working on the Mozilla codebase

Beginnings of MDN

The site that became MDN, developer.mozilla.org or “Devmo,” started as a redirect to a developer-oriented page on the main mozilla.org site. Later that content was moved over to Devmo; it contained primarily information for developers contributing to the Mozilla codebase.

Just as the Mozilla project emerged from the remains of Netscape, also MDN as we know it began with documentation originally written at Netscape. The site known as “Netscape DevEdge” documented web technologies, such as JavaScript, and other things that were implemented in Netscape products. After Netscape was acquired by AOL, the DevEdge site eventually was shut down, and that information disappeared from the Web.

Mitchell Baker (Chair of Mozilla) and others from Mozilla worked out an arrangement with AOL to release the DevEdge content, which she announced in February 2005. At the same time, Deb Richardson was hired to migrate and curate the DevEdge content into Devmo.

Mitchell and Deb made the decision to put the content into a wiki, to enable open contributions to maintain and update the content. Previously, the DevEdge content was in a CVS source control system, and published as a static site. Using a wiki for documentation was a novel concept at the time, and it took a while for some core developers within the Mozilla project to warm to this way of working. However, others quickly embraced the idea, and the many of the earliest contributors to the Devmo wiki were developers who were active elsewhere in the Mozilla project.

Deb and some volunteers spent a few months mining and migrating the still-useful content from DevEdge, working on a test server. This effort was still in progress when the content was migrated to the Devmo site, now titled “Mozilla Developer Center” or “MDC” in July 2005. We mark this as the starting point of what we now call Mozilla Developer Network.

Platform evolution

MDN has lived on three different wiki platforms in the course of its history: first MediaWiki, then MindTouch DekiWiki, and now Kuma, a Mozilla-developed platform. Looking at the technical infrastructure is interesting not just from a technical point of view, but also because technology influences social structures like community.

MediaWIki

The wiki platform used for the first iteration of MDC was MediaWiki, the open source software that underlies Wikipedia. It was the most robust and widely-used wiki at the time. The Devmo project began to discover that software designed for writing a general-purpose encyclopedia was not necessarily ideal for writing developer-oriented technical documentation. For example, it did not handle code examples well, reformatting them to be unreadable. Mozilla tried to fix such issues by creating its own fork of MediaWiki, which then ended up being quite difficult to maintain.

On the level of contributions, using MediaWiki was initially an advantage, because many technical people were already familiar with how to use it. However, the project eventually reached a plateau, where it became difficult to keep contributors coming back. This, combined with the technical quirks, led to a search for a more user-friendly platform.

Dekiwiki

After an evaluation process that looked at all the wiki products available on the market (not just open source ones), the choice was made of DekiWiki by MindTouch. One advantage of DekiWiki was that the source format for articles was HTML, rather than wiki markup. It seemed a logical choice for a site targeting web developers, to have the source format be a standard web language. This required migrating all of the content from MediaWiki markup format to HTML, which was a major migration project. The choice of DekiWiki was announced in November 2007, and the site switched to it in August 2008.

While DekiWiki was a quality product, one way that the selection process was flawed was that it did not include a major group of stakeholders: volunteers who contributed to the site. The rate of contribution nose-dived, because the platform was not embraced by the contributor community. In particular, localization communities, who translated the content into various languages other than English, were severely disrupted. They had built tools and processes around working with MediaWiki, and these tools didn’t work with DekiWiki. After a few months, many of these groups simply disbanded and decided not to contribute any more, with the result that translated documentation started to become stale, and became more and more out of date over time.

DekiWiki was also written in C#, and designed to run in a Microsoft .NET environment. This was a mismatch with Mozilla’s technical infrastructure, which is Linux-based. Trying to run DekiWiki on Mono led to a great deal of instability, with the site being down for days and weeks at times.

These issues, after a couple of years, led to looking for another solution. The best candidates on the market were still MediaWiki and DekiWiki. Now that the content was all written in HTML, migrating back to MediaWiki markup syntax was not feasible. No product seemed suited to the specific needs of an open developer documentation site, so Mozilla decided to create its own.

Kuma

The current platform for MDN, known as Kuma, is written in Python with Django. It started as a fork of Kitsune, the platform for the Mozilla support site, and was adapted to the needs of a wiki site for developers rather than end users. (Also, “kitsune” means “fox” in Japanese, and “kuma” means “bear”. Because users : foxes :: developers : bears, right?)

Like DekiWiki, Kuma uses HTML as the source format for the content. The migration effort in this case was converting the scripts and macros used on the site. DekiWiki used “DekiScript,” based on Lua, while Kuma introduced KumaScript, which is based on JavaScript, using Node.js. KumaScript is the brainchild of developer Les Orchard. As with creating content in HTML, KumaScript means that MDN is implemented using the same technologies that it documents, and that its contributors are familiar with. It was possible to migrate about 70% of the existing macros automatically, but the rest had to be manually converted.

The goal when launching the Kuma platform was to achieve feature parity with the DekiWiki implementation of MDN. The content was migrated to the new system, and changes from the production server were periodically updated on the Kuma staging server. Thus, the Kuma instance was kept in sync with the production DekiWiki server. While the months leading up to the launch of Kuma were involved a great deal of migration work, the actual launch was very smooth. A routing switch was flipped, and traffic shifted to the new site seamlessly, without even disrupting login sessions.

Community evolution

From the beginning, the community for the DevMo site grew organically, starting with contributors who were already active in other parts of the Mozilla project. Like other areas of Mozilla, communication happens through a mailing list and IRC chat channel. By mid-2007, contributions were typically 250 per month. As mentioned before, the migration to Dekiwiki led to a dramatic drop-off in localization contribution, and total contribution declined as well.

As part of an effort to engage the community more actively, I (Janet Swisher) was hired as a staff technical writer in mid-2010. I brought experience with open source developer documentation, and in particular, experience with the “book sprints” methodology used by the FLOSS Manuals project to produce manuals for free software in five days or less. The first MDN “doc sprint” took place in October 2010, in the Mozilla Paris office. Doc sprints bring together a number of MDN contributors, either physically or virtually, for focussed, collaborative work, typically over a weekend. These were held about once a quarter for about three years. More recently, they have evolved into less frequent but broader “Hack on MDN” events, whose scope includes hacking on the platform or tools, as well as on content, to make them more attractive to developers.

In addition, the MDN community holds a number of regular online meetings, both for general information, and for tracking specific projects. These community activities, as well as the migration to Kuma in 2012, have led to a significant increase in contributions, now around 1000 per month.

Branding evolution

In the beginning, the DevMo site was known as “Mozilla Developer Center.” At first, it simply sported that title, with a simple skin on MediaWiki. With the move to DekiWiki, the word “Mozilla” became the Mozilla wordmark, followed by “

In September 2010, the name of the site was changed from “Mozilla Developer Center” to “Mozilla Developer Network” or MDN. This change was met with some skepticism from the developer audience at the time, though by now they simply accept MDN as MDN. The visual design of the site changed at the same time, to a darker theme, and MDN acquired a logo, the “robot dino,” which it had never had before.

Along with these visual changes, features were added to the site to broaden its scope beyond just documentation. One successful feature is known as “Demo Studio”, an area where developers can upload code demos, share them, and show them off.When MDN migrated from DekiWiki to Kuma, the visual appearance was preserved, so there was very little visual difference between the pre- and post-migration sites. After six to eight months of bug-fixing on Kuma, a project was started to change not only the visual design, but also the content structure. These changes were rolled out using feature flags, to users who chose to be beta testers. Thus, while most users continued to see the old design, while beta testers saw and tested the new visuals and structure. “Launch day” for the redesign consisted of simply flipping a switch in the database to make the new features visible to everybody.

The redesign brought not only a new logo, the dino-head-map that we see today, but also structural features like the navigation sidebar, which varies depending on which content area an article is in. In localized pages, items in the sidebar that are not yet translated link to their English versions, and show an invitation to translate them.

Content evolution

We mark the start of MDN “as we know it” from the acquisition and republication of the Netscape DevEdge content in 2005. But in the early days, the content was very slanted toward Mozilla products and technology. Not only was there documentation of XUL and internal Mozilla APIs (which are still there), but documentation of web technologies tended to be focused on Mozilla and Firefox, for example, with big banners like “works in Firefox 2.0'' or explanations of Gecko’s support of a feature in the middle of an otherwise neutral article.

As Mozilla began engaging more actively with the MDN community in 2010, community members began to express a vision of MDN as a vendor-neutral resource for web developers, whatever browsers they are targeting. Adopting this as a strategy required a lot of clean-up effort to remove Firefox-specific content from articles about web standards, and to create the compatibility tables that exist now, with information about all major browsers. Not coincidentally, as the content on MDN became more browser-agnostic, MDN started seeing contributions from other organizations.

MDN today and tomorrow

Two current projects on MDN are having a major impact on the shape of MDN in the near to medium term: the Learning area, and the compatibility data project.

MDN’s information about web technologies has long been a resource for experienced web developers. But it has poorly supported beginners to web development. The aim of the Learning area is to change that by offering tutorials and other resources to people who want to teach themselves about web development. This effort is happening in response to surveys we’ve done of our audience, who reported basic learning material as a significant gap. The Learning area project has been underway for about a year, and in that time has created a large Glossary about web technology concepts, and a number of new tutorials, corresponding to the Web Literacy Map developed by the Mozilla Foundation. The Learning area is a great opportunity to get started in contributing to MDN, since learners and teachers are as needed as technical experts.

Currently, data on MDN about browsers’ compatibility with web technology features is maintained in tables on the relevant pages. The data is pretty good, thanks to many, many crowd-sourced contributions. But this approach is not very sustainable or maintainable; for example, every table must be replicated on all localized versions of the page. The compatibility data project aims to improve the quality of the data, make data contribution easier, make access to the data easier, and allow reuse of the data, through a centralized data store. This project is action-driven rather than time-bound; contributions and involvement are welcome.

MDN in 10 years?

MDN as it exists today is quite different from its beginnings ten years ago. The Web has evolved, Mozilla has evolved, and MDN has evolved. We can expect even greater changes in the next ten years. Perhaps the vision of a direct brain interface to virtual reality “cyberspace” will finally come to pass. We know for sure there will be many more web developers, many more types of devices, and many standards that are not yet written.

Some things won’t change: Mozilla’s mission will continue to be to work towards an Internet that is a global public resource, open and accessible for all. MDN will continue to be a means towards that mission, by providing resources to enable anyone to become a creator of the Web, and to develop on the Web as a primary platform. MDN’s content, no matter how it’s delivered, will continue to be contributed by a global community of people who are passionate about learning and sharing knowledge about the Web.

http://blog.mozilla.org/community/2015/07/23/ten-years-of-evolution-of-mdn/

|

|

Air Mozilla: July Brantina on Prototyping with Tom Chi |

At this month's July 23 Brantina Tom Chi (one of the founders of GoogleX) will share some best practices as well as things to avoid...

At this month's July 23 Brantina Tom Chi (one of the founders of GoogleX) will share some best practices as well as things to avoid...

https://air.mozilla.org/july-brantina-on-prototyping-with-tom-chi/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: MDN celebrates 10 years of documenting YOUR Web |

Today, Mozilla proudly celebrates the 10th anniversary of the Mozilla Developer Network, one of the richest and also one of the few multilingual resources on the Web for documentation. It started in February 2005, when a small team dedicated to the open Web took DevEdge (Netscape’s developer materials) and set out to create an open, free, community-built online resource for all Web developers. Just a couple of months later, on 23 July, 2005 the original MDN wiki site launched and has evolved steadily ever since for the convenience and the benefit of its users.

Today, ten years later, not only has the amount of documentation grown – 34,500 documents and climbing – but also MDN’s global volunteer community is bigger than ever. Currently, MDN has more than 4 million users and over 1000 volunteer editors per month creating and translating documentation, sample code, tutorials and other learning resources for all open Web technologies, including CSS, HTML, JavaScript and everything that makes the open Web as rich and versatile as it is.

For a wide range of Web developers, from learners to hobbyists to full-time professionals, MDN provides useful explanations for coding practice. It aims to inspire ideas, encourage collaboration, innovation and ultimately, foster the growth of the open Web. Moreover, as the digital industry flourishes and the demand for coding skills at young age rises, the importance of well-organized resources like MDN grows exponentially. That is why in 2014 MDN started to feed and expand all its learning pages into a “Learn the Web” area for beginning web developers, including a web terminology glossary, which MDN’s technical writers and volunteers will continue to develop over the next years.

All these efforts, which would not be possible without the active MDN volunteer base, are being greatly acknowledged by developers from all over the world who would not be doing what they do without MDN – or at least not as good.

Let’s hear it for MDN!

For more information:

Web: https://developer.mozilla.org/

MDN at 10: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/MDN_at_ten

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MozDevNet

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2015/07/23/mdn-celebrates-10-years-of-documenting-your-web/

|

|

Weekly Mozilla Reps call

Weekly Mozilla Reps call