Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Mozilla VR Blog: Firefox Reality 10 |

Our team has been hard at work on the latest version of Firefox Reality. In our last two versions, we had a heightened focus on performance and stability. With this release, fans of our browser on standalone VR headsets can enjoy the best of both worlds—a main course of in-demand features, with sides of performance and UI improvements. Firefox Reality 10 is a feature-packed release with something for every VR enthusiast.

But perhaps the most exciting news of this release is we’re releasing in conjunction with our new partner, Pico Interactive! We’re teaming up to bring the latest and greatest in VR browsing to Pico’s headsets, including the Neo 2 – an all-in-one (AIO) device with 6 degrees of freedom (DoF) head and controller tracking. Firefox Reality will be released and shipped with all Pico headsets. Learn more about what this partnership means here. And check out Firefox Reality in the Pico store.

What's New?

But what about all the exciting features we served up in this release, you might ask? Let’s dig in!

You Are Now Entering WebXR

Firefox Reality now supports WebXR! WebXR is the successor to the WebVR spec. It provides a host of improvements in cross-device functionality and tooling for both VR and AR applications. With WebXR, a site can support a wide variety of controller devices without writing support for each one individually. WebXR takes care of choosing the right controls for actions such as selecting and grabbing objects.

You can get started right now using WebXR applications in Firefox Reality 10. If you’re looking for ways to get started building your own WebXR applications, take a look at the MDN Docs for the WebXR API. And if you’re already working with Unity and want to explore developing WebXR applications, check out our Unity WebXR Exporter.

Making the transition from WebVR to WebXR

We understand WebXR support among the most widely used browsers is fairly new and the community has largely been developing for WebVR until very recently. We want to help people to get to WebXR, but the vast majority of web content that is VR-enabled is WebVR content—twenty-five percent (25%) of our users consume WebVR content. Not to worry, we've got you covered.

This release also continues our support for WebVR, making Firefox Reality 10 the only standalone browser that supports both WebVR and WebXR experiences.

This will help our partners and developer community gracefully transition to WebXR without worrying that their audiences will lose functionality immediately. We will eventually deprecate WebVR. We’re currently working on a timeline for removing WebVR support, but we’ll share that timeline with our community well in advance of any action.

Gaze Support

Another useful feature included in this release is gaze navigation support. This allows viewers to navigate within the browser without controllers, using only head movement and headset buttons. This is great for users who may not be able to use controllers, or for use with headsets that don’t include controllers or allow you unbind controllers. See a quick demo of this feature on the Pico Neo 2 below. Here we’re able to scroll, select and type, all without the use of a physical controller.

Dual-controller typing

Many of us know how tedious it can be to type on a virtual keyboard with one controller. Additionally, one-hand typing may be counter-intuitive for those who are used to typing with two hands in most environments. With this version we’re introducing dual-controller typing to create a more natural keyboard experience.

Download Management

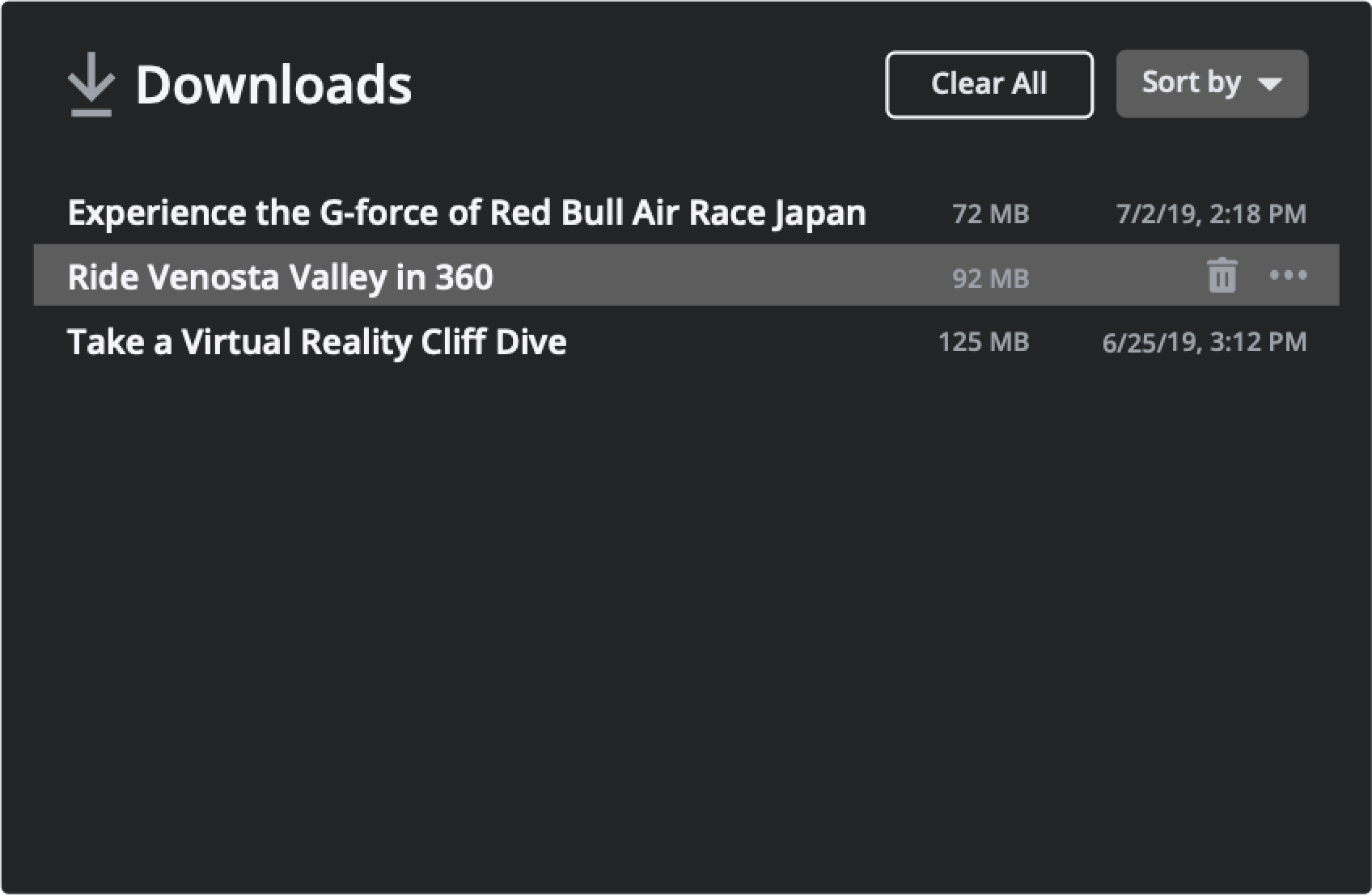

This version allows users to download files and manage previously downloaded files. Users can now view, sort and delete downloads without leaving the browser.

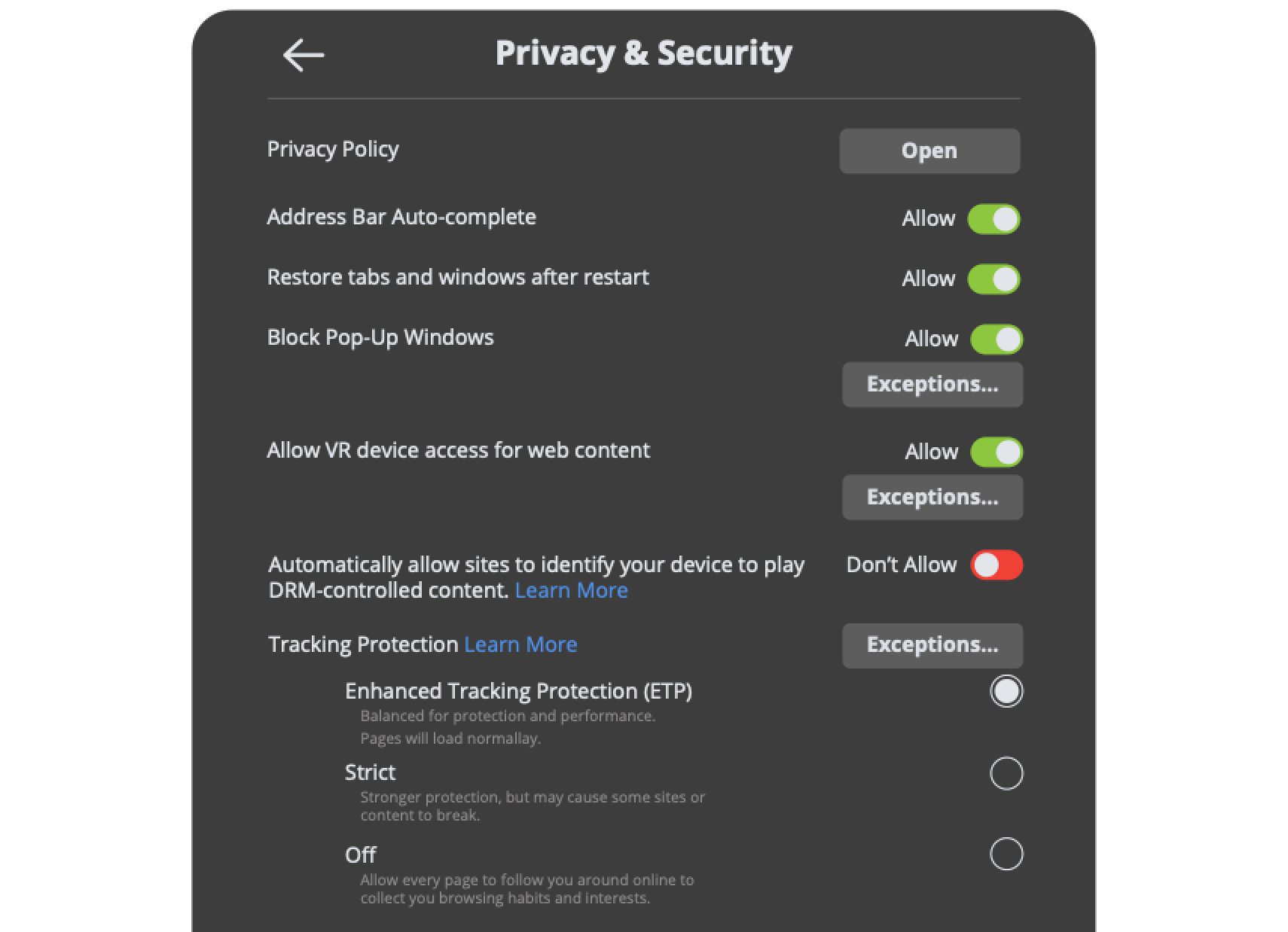

Enhanced Tracking Protection

At Mozilla, we always want to enable our users to take their privacy and security into their own hands. Our enhanced tracking protection makes users aware of potential privacy issues and allows users to fully control their privacy settings--from notifications of user activity tracking to our updated "Privacy and Security" UI.

These highlighted features, along with the many performance, DRM video playback and user experience improvements we’ve included make this a must-try release. Download it today in the Pico, HTC and Oculus app stores.

Contribute to Firefox Reality!

Firefox Reality is an open source project. We love hearing from and collaborating with our developer community. Check out Firefox Reality on GitHub and help build the open immersive web.

|

|

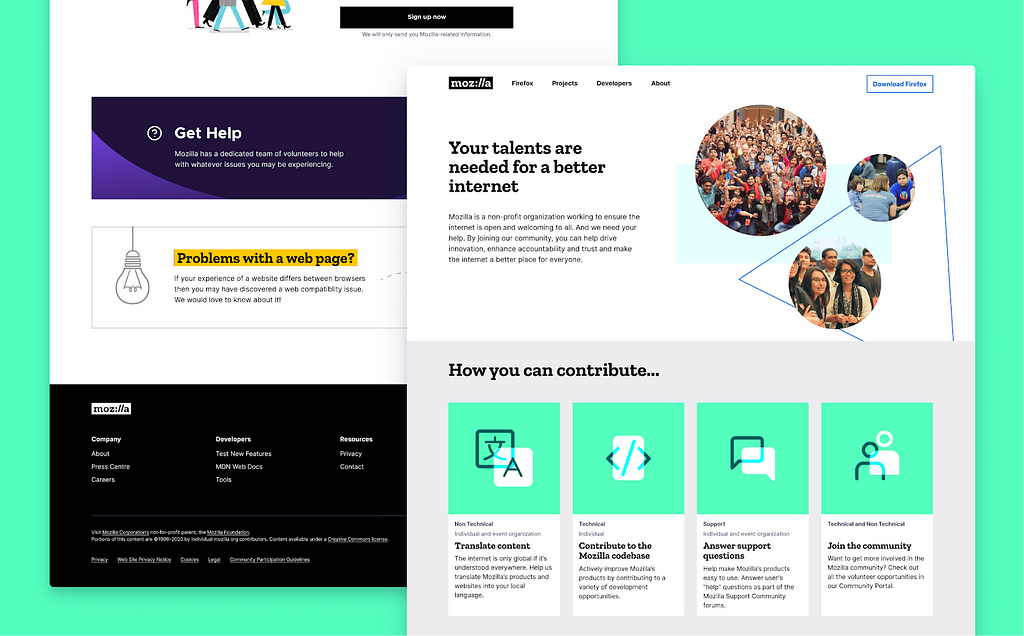

Mozilla Open Innovation Team: Redesigning Mozilla’s Contribute Page: A UX Overview |

The previous Contribute page on Mozilla.org received around 100,000 views a month and had a 70% bounce rate.

For page engagements just over 1% of those viewers clicked on the “Get Involved” button, taking them to the Mozilla Activate page.

We wanted to change that.

We began this redesign project with a discovery phase. As a result of the strict environment the page would live in, all of our assumption testing had to be carried out through upfront discovery research as opposed to evaluative A/B testing post design.

We started to collate previous findings and analysis, drawing conclusions from past efforts like the Contribute Survey Analysis carried out in 2019.

With a broad idea of what visitors are looking for we looked internally with stakeholder interviews. A series of one to one remote meetings with Mozilla community staff were scheduled to uncover their hopes for a redesign and what they felt the current offering lacked. From this, two themes emerged:

- A need to describe what the community and contribution look like.

- Illustrating the breadth of volunteer opportunities.

The next exercise was to address the copy of the page. Using both analytics data and stakeholder feedback a series of “content blocks” were arranged to define what content we needed and the hierarchy it belonged in. A copywriter and marketing team member would review an initial draft however this was sufficient to populate wireframes for testing purposes.

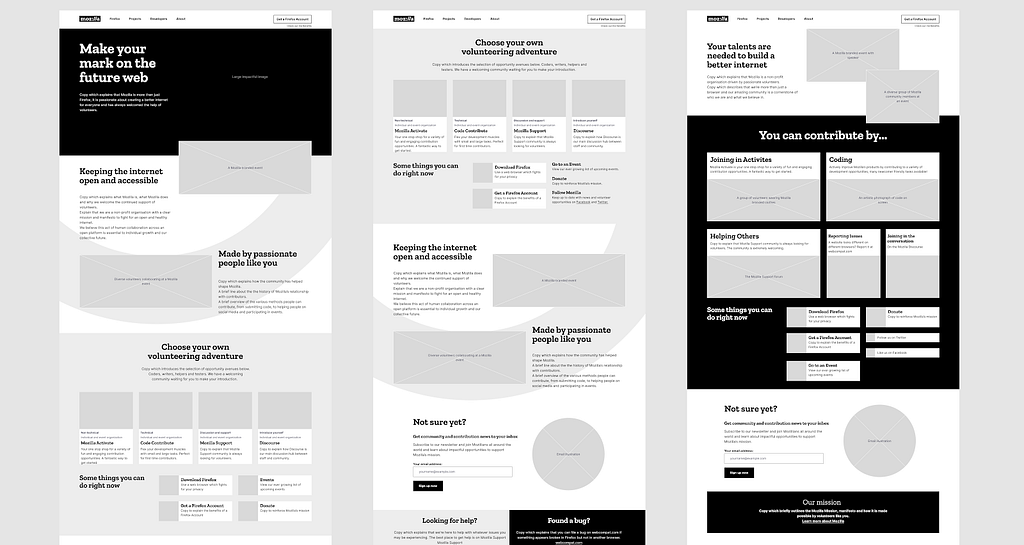

Three wireframe layouts were produced, each putting slightly more emphasis on a different element of the page. One focused on telling a story, another focused on providing the widest volunteer entry points and the final layout was tasked with being direct and minimal.

The Mozilla All Hands Event in Berlin was the perfect opportunity to gather some feedback from existing contributors. Both volunteers and staff were asked upfront questions about their expectations of a volunteer page before being presented with large printouts of each wireframe for review.

The community feedback was overwhelming with an emerging trend. “Story” was appreciated, however it was sufficient to know it was there “somewhere”. Conversely, volunteer opportunities needed to be clear and relatively upfront.

There was one additional research method we could utilise before casting some of our findings into design, remote unmoderated usability testing. With the ability to target participants with existing volunteer experience, we presented three wireframes to separate groups, again asking upfront questions on their expectations before revealing each design.

In three key ways the findings echoed the feedback of the All Hands interviews.

- An appreciation for a little upfront story, but not too much.

- An explicit, straight-talking tone was a clear preference.

- Volunteer opportunities should not be buried within the page.

Some additional findings revealed:

- Participants liked to see the opportunities categorised as either Technical or Non Technical.

- Participants were keen to understand the time and travel investment of each opportunity.

The feedback of the following research methods gave the team a shared vision of the final product before it had been designed:

- Stakeholder interviews

- User interviews

- Guerilla usability testing

- Unmoderated remote usability testing

Merging the copy approved content with Mozilla brand guidelines, a selection of designs were delivered and shared with the team for asynchronous feedback. After a final group call and some final tweaks we had our new Contribute page design ready for development.

The page design pays various tributes to the Mozilla Community Portal, fitting, as both projects wish to serve Mozilla’s new and existing volunteer communities.

We will be monitoring the success of the page over time to determine the impact of the research-lead redesign. You can visit the new Contribute page on the Mozilla website, maybe you’ll discover something new about Mozilla when you get there!

Redesigning Mozilla’s Contribute Page: A UX Overview was originally published in Mozilla Open Innovation on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Building FunctionTrace, a graphical Python profiler |

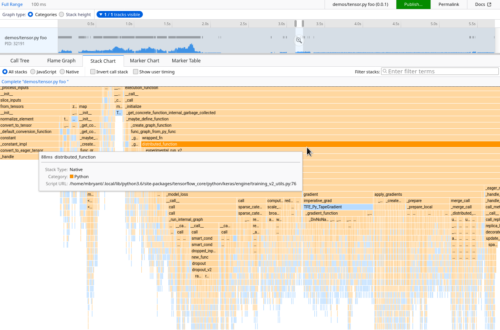

Firefox Profiler for performance analysis

Harald’s Introduction

Firefox Profiler became a cornerstone of Firefox’s performance work in the days of Project Quantum. When you open up an example recording, you first see a powerful web-based performance analysis interface featuring call trees, stack charts, flame graphs, and more. All data filtering, zooming, slicing, transformation actions are preserved in a sharable URL. You can share it in a bug, document your findings, compare it side-by-side with other recordings, or hand it over for further investigation. Firefox DevEdition has a sneak peek of a built-in profiling flow that makes recording and sharing frictionless. Our goal is to empower all developers to collaborate on performance – even beyond Firefox.

Early on, the Firefox Profiler could import other formats, starting with Linux perf and Chrome’s profiles. More formats were added over time by individual developers. Today, the first projects are emerging that adopt Firefox for analysis tools. FunctionTrace is one of these, and here is Matt to tell the story of how he built it.

Meet FunctionTrace, a profiler for Python code

Matt’s Project

I recently built a tool to help developers better understand what their Python code is doing. FunctionTrace is a non-sampled profiler for Python that runs on unmodified Python applications with very low (<5%) overhead. Importantly, it’s integrated with the Firefox Profiler. This allows you to graphically interact with profiles, making it easier to spot patterns and make improvements to your codebase.

In this post, I’ll discuss why we built FunctionTrace, and share some technical details of its implementation. I’ll show how tools like this can target the Firefox Profiler as a powerful open-source visualization tool. To follow along, you can also play with a small demo of it!

Technical debt as motivation

Codebases tend to grow larger over time, especially when working on complex projects with many people. Some languages have great support for dealing with this, such as Java with its IDE capabilities built up over decades, or Rust with its strong type system that makes refactoring a breeze. Codebases in other languages sometimes seem to become increasingly less maintainable as they grow. This is particularly true in older Python codebases (at least we’re all on Python 3 now, right?).

It can be extremely difficult to make broad changes or refactor pieces of code you’re not familiar with. In contrast, I have a much easier time making correct changes when I’m able to see what a program is doing and all its interactions. Often, I even find myself making improvements to pieces of the code that I’d never intended to touch, as inefficiencies become glaringly obvious when presented on my screen.

I wanted to be able to understand what the Python codebases I work in were doing without needing to read through hundreds of files. I was unable to find existing tools for Python that were satisfactory, and I mostly lost interest in building a tool myself due the amount of UI work that would be necessary. However, when I stumbled across the Firefox Profiler, my hopes of quickly understanding a program’s execution were reignited.

The Profiler provided all of the “hard” pieces – an intuitive open-source UI that could display stack charts, time-correlated log markers, a flame graph, and the stability that comes from being tied to a major web browser. Any tool able to emit a properly-formatted JSON profile would be able to reuse all of the previously mentioned graphical analysis features.

Design of FunctionTrace

Luckily, I already had a week of vacation scheduled for a few days after I discovered the Firefox Profiler. I knew another friend who was interested in building it with me and also taking time off that week.

Goals

We had several goals when we started to build FunctionTrace:

- Give the ability to see everything occurring in the program.

- Handle multi-threaded/multi-process applications.

- Be low-overhead enough that we could use it without a performance tradeoff.

The first goal had a significant impact on the design, while the latter two added engineering complexity. From past experience with tools like this, we both knew the frustration of not being able to see function calls that are too short. When you’re sampling at 1ms but have important functions that run faster than that, you miss significant pieces of what’s occurring inside your program!

As a result, we knew we’d need to be able to trace all function calls and could not use a sampling profiler. Additionally, I’d recently spent time in a codebase where Python functions would exec other Python code (frequently via an intermediary shell script). From this, we knew we’d want to be able to also trace descendant Python processes.

Initial implementation

To support multiple processes and descendants, we settled on a client-server model. We’d instrument Python clients, which would send trace data to a Rust server. The server would aggregate and compress the data before generating a profile that could be consumed by the Firefox Profiler. We chose Rust for several reasons, including the strong type system, a desire for stable performance and predictable memory usage, and ease of prototyping and refactoring.

We prototyped the client as a Python module, called via python -m functiontrace code.py. This allowed us to easily use Python’s builtin tracing hooks to log what was executed. The initial implementation looked very similar to the following:

def profile_func(frame, event, arg):

if event == "call" or event == "return" or event == "c_call" or event == "c_return":

data = (event, time.time())

server.sendall(json.dumps(data))

sys.setprofile(profile_func)

For the server, we listened on a Unix domain socket for client connections. Then we read data from the client and converted them into Firefox Profiler’s JSON format.

The Firefox Profiler supports various profile types, such as perf logs. However, we decided to emit directly to the Profiler’s internal format. It requires less space and maintenance than adding a new supported format. Importantly, the Firefox Profiler maintains backwards compatibility for profile versions. This means that any profile we emit targeting the current format version will be automatically converted to the latest version when loaded in the future. Additionally, the profiler format references strings by integer IDs. This allows significant space savings via deduplication (while being trivial to implement using indexmap).

A few optimizations

Generally, the initial base worked. On every function call/return Python would call our hook. The hook would then send a JSON message out over a socket for the server to convert into the proper format. However, it was incredibly slow. Even after batching the socket calls, we observed at least 8x overhead on some of our test programs!

At this point, we dropped down to C using Python’s C API instead. We got down to 1.1x overhead on the same programs. After that, we were able to do another key optimization by replacing calls to time.time() with rdtsc operations via clock_gettime(). We reduced the performance overhead for function calls to a few instructions and emitting 64 bits of data. This was much more efficient than having a chain of Python calls and complex arithmetic in the critical path.

I’ve mentioned that we support tracing multiple threads and descendant processes. Since this was one of the more difficult pieces of the client, it’s worth discussing some lower-level details.

Supporting multiple threads

We install a handler on all threads via threading.setprofile(). (Note: we register via a handler like this when we’re setting up our thread state to ensure that Python is running and the GIL is currently held. This allows us to simplify some assumptions.):

// This is installed as the setprofile() handler for new threads by

// threading.setprofile(). On its first execution, it initializes tracing for

// the thread, including creating the thread state, before replacing itself with

// the normal Fprofile_FunctionTrace handler.

static PyObject* Fprofile_ThreadFunctionTrace(..args..) {

Fprofile_CreateThreadState();

// Replace our setprofile() handler with the real one, then manually call

// it to ensure this call is recorded.

PyEval_SetProfile(Fprofile_FunctionTrace);

Fprofile_FunctionTrace(..args..);

Py_RETURN_NONE;

}

When our Fprofile_ThreadFunctionTrace() hook is called, it allocates a struct ThreadState, which contains information the thread will need to log events and communicate to the server. We then send an initial message to the profile server. Here we notify it that a new thread has started and provide some initial information (time, PID, etc). After this initialization, we replace the hook with Fprofile_FunctionTrace(), which does the actual tracing in the future.

Supporting descendant processes

When handling multiple processes, we make the assumption that children are being run via a python interpreter. Unfortunately, the children won’t be called with -m functiontrace, so we won’t know to trace them. To ensure that children processes are traced, on startup we modify the $PATH environment variable. In turn, this ensures python is pointing to an executable that knows to load functiontrace.

# Generate a temp directory to store our wrappers in. We'll temporarily

# add this directory to our path.

tempdir = tempfile.mkdtemp(prefix="py-functiontrace")

os.environ["PATH"] = tempdir + os.pathsep + os.environ["PATH"]

# Generate wrappers for the various Python versions we support to ensure

# they're included in our PATH.

wrap_pythons = ["python", "python3", "python3.6", "python3.7", "python3.8"]

for python in wrap_pythons:

with open(os.path.join(tempdir, python), "w") as f:

f.write(PYTHON_TEMPLATE.format(python=python))

os.chmod(f.name, 0o755)

Inside the wrappers, we simply need to call the real python interpreter with the additional argument of -m functiontrace. To wrap this support up, on startup we add an environment variable. The variable says what socket we’re using to communicate to the profile server. If a client initializes and sees this environment variable already set, it recognizes a descendant process. It then connects to the existing server instance, allowing us to correlate its trace with that of the original client.

Current implementation

The overall implementation of FunctionTrace today shares many similarities with the above descriptions. At a high level, the client is traced via FunctionTrace when invoked as python -m functiontrace code.py. This loads a Python module for some setups, then calls into our C module to install various tracing hooks. These hooks include the sys.setprofile hooks mentioned above, memory allocation hooks, and custom hooks on various “interesting” functions, like builtins.print or builtins.__import__. Additionally, we spawn a functiontrace-server instance, setup a socket for talking to it, and ensure that future threads and descendant processes will be talking to the same server.

On every trace event, the Python client emits a small MessagePack record. The record contains minimal event information and a timestamp to a thread-local memory buffer. When the buffer fills up (every 128KB), it is dumped to the server via a shared socket and the client continues to execute. The server listens asynchronously to each of the clients, quickly consuming their trace logs into a separate buffer to avoid blocking them. A thread corresponding to each client is then able to parse each trace event and convert it into the proper end format. Once all connected clients exit, the per-thread logs are aggregated into a full profile log. Finally, this is emitted to a file, which can then be used with the Firefox Profiler.

Lessons learned

Having a Python C module gives significantly more power and performance, but comes with costs. it requires more code, it’s harder to find good documentation; and few features are easily accessible. While C modules appear to be an under-utilized tool for writing high performance Python modules (based on some FunctionTrace profiles I’ve seen), we’d recommend a balance. Write most of the non-performance critical code in Python and call into inner loops or setup code in C, for the pieces where Python doesn’t shine.

JSON encoding/decoding can be incredibly slow when the human-readable aspect isn’t necessary. We switched to MessagePack for client-server communication and found it just as easy to work with while cutting some of our benchmark times in half!

Multithreading profiling support in Python is pretty hairy, so it’s understandable why it doesn’t seem to have been a key feature in previous mainstream Python profilers. It took several different approaches and many segfaults before we had a good understanding of how to operate around the GIL while maintaining high performance.

Please extend the profiler ecosystem!

This project wouldn’t have existed without the Firefox Profiler. It would’ve simply been too time-consuming to create a complex frontend for an unproven performance tool. We hope to see other projects targeting the Firefox Profiler, either by adding native support for the Profiler format like FunctionTrace did, or by contributing support for their own formats. While FunctionTrace isn’t entirely done yet, I hope sharing it on this blog can make other crafty developers aware of the Firefox Profiler’s potential. The Profiler offers a fantastic opportunity for some key development tooling to move beyond the command line and into a GUI that’s far better suited for quickly extracting relevant information.

The post Building FunctionTrace, a graphical Python profiler appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2020/05/building-functiontrace-a-graphical-python-profiler/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: AI-powered code submissions |

Who knows, maybe May 18 2020 will mark some sort of historic change when we look back on this day in the future.

On this day, the curl project received the first “AI-powered” submitted issues and pull-requests. They were submitted by MonocleAI, which is described as:

MonocleAI, an AI bug detection and fixing platform where we use AI & ML techniques to learn from previous vulnerabilities to discover and fix future software defects before they cause software failures.

I’m sure these are still early days and we can’t expect this to be perfected yet, but I would still claim that from the submissions we’ve seen so far that this is useful stuff! After I tweeted about this “event”, several people expressed interest in how well the service performs, so let me elaborate on what we’ve learned already in this early phase. I hope I can back in the future with updates.

Disclaimers: I’ve been invited to try this service out as an early (beta?) user. No one is saying that this is complete or that it replaces humans. I have no affiliation with the makers of this service other than as a receiver of their submissions to the project I manage. Also: since this service is run by others, I can’t actually tell how much machine vs humans this actually is or how much human “assistance” the AI required to perform these actions.

I’m looking forward to see if we get more contributions from this AI other than this first batch that we already dealt with, and if so, will the AI get better over time? Will it look at how we adjusted its suggested changes? We know humans adapt like that.

Pull-request quality

Monocle still needs to work on adapting its produced code to follow the existing code style when it submits a PR, as a human would. For example, in curl we always write the assignment that initializes a variable to something at declaration time immediately on the same line as the declaration. Like this:

int name = 0;

… while Monocle, when fixing cases where it thinks there was an assignment missing, adds it in a line below, like this:

int name;

name = 0;

I can only presume that in some projects that will be the preferred style. In curl it is not.

White space

Other things that maybe shouldn’t be that hard for an AI to adapt to, as you’d imagine an AI should be able to figure out, is other code style issues such as where to use white space and where not no. For example, in the curl project we write pointers like char * or void *. That is with the type, a space and then an asterisk. Our code style script will yell if you do this wrong. Monocle did it wrong and used it without space: void*.

C89

We use and stick to the most conservative ANSI C version in curl. C89/C90 (and we have CI jobs failing if we deviate from this). In this version of C you cannot mix variable declarations and code. Yet Monocle did this in one of its PRs. It figured out an assignment was missing and added the assignment in a new line immediately below, which of course is wrong if there are more variables declared below!

int missing; missing = 0; /* this is not C89 friendly */ int fine = 0;

NULL

We use the symbol NULL in curl when we zero a pointer . Monocle for some reason decided it should use (void*)0 instead. Also seems like something virtually no human would do, and especially not after having taken a look at our code…

The first issues

MonocleAI found a few issues in curl without filing PRs for them, and they were basically all of the same kind of inconsistency.

It found function calls for which the return code wasn’t checked, while it was checked in some other places. With the obvious and rightful thinking that if it was worth checking at one place it should be worth checking at other places too.

Those kind of “suspicious” code are also likely much harder fix automatically as it will include decisions on what the correct action should actually be when checks are added, or perhaps the checks aren’t necessary…

Credits

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2020/05/20/ai-powered-code-submissions/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: curl ootw: –range |

--range or -r for short. As the name implies, this option is for doing “range requests”. This flag was available already in the first curl release ever: version 4.0. This option requires an extra argument specifying the specific requested range. Read on the learn how!

What exactly is a range request?

Get a part of the remote resource

Maybe you have downloaded only a part of a remote file, or maybe you’re only interested in getting a fraction of a huge remote resource. Those are two situations in which you might want your internet transfer client to ask the server to only transfer parts of the remote resource back to you.

Let’s say you’ve tried to download a 32GB file (let’s call it a huge file) from a slow server on the other side of the world and when you only had 794 bytes left to transfer, the connection broke and the transfer was aborted. The transfer took a very long time and you prefer not to just restart it from the beginning and yet, with many file formats those final 794 bytes are critical and the content cannot be handled without them.

We need those final 794 bytes! Enter range requests.

With range requests, you can tell curl exactly what byte range to ask for from the server. “Give us bytes 12345-12567” or “give us the last 794 bytes”. Like this:

curl --range 12345-12567 https://example.com/

and:

curl --range -794 https://example.com/

This works with curl with several different protocols: HTTP(S), FTP(S) and SFTP. With HTTP(S), you can even be more fancy and ask for multiple ranges in the same request. Maybe you want the three sections of the resource?

curl --range 0-1000,2000-3000,4000-5000 https://example.com/

Let me again emphasize that this multi-range feature only exists for HTTP(S) with curl and not with the other protocols, and the reason is quite simply that HTTP provides this by itself and we haven’t felt motivated enough to implement it for the other protocols.

Not always that easy

The description above is for when everything is fine and easy. But as you know, life is rarely that easy and straight forward as we want it to be and nether is the --range option. Primarily because of this very important detail:

Range support in HTTP is optional.

It means that when curl asks for a particular byte range to be returned, the server might not obey or care and instead it delivers the whole thing anyway. As a client we can detect this refusal, since a range response has a special HTTP response code (206) which won’t be used if the entire thing is sent back – but that’s often of little use if you really want to get the remaining bytes of a larger resource out of which you already have most downloaded since before.

One reason it is optional for HTTP and why many sites and pages in the wild refuse range requests is that those sites and pages generate contend on demand, dynamically. If we ask for a byte range from a static file on disk in the server offering a byte range is easy. But if the document is instead the result of lots of scripts and dynamic content being generated uniquely in the server-side at the time of each request, it isn’t.

HTTP 416 Range Not Satisfiable

If you ask for a range that is outside of what the server can provide, it will respond with a 416 response code. Let’s say for example you download a complete 200 byte resource and then you ask that server for the range 200-202 – you’ll get a 416 back because 200 bytes are index 0-199 so there’s nothing available at byte index 200 and beyond.

HTTP other ranges

--range for HTTP content implies “byte ranges”. There’s this theoretical support for other units of ranges in HTTP but that’s not supported by curl and in fact is not widely used over the Internet. Byte ranges are complicated enough!

Related command line options

curl also offers the --continue-at (-C) option which is a perhaps more user-friendly way to resume transfers without the user having to specify the exact byte range and handle data concatenation etc.

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: Help curl: the user survey 2020 |

The annual curl user survey is up. If you ever used curl or libcurl during the last year, please consider donating ten minutes of your time and fill in the question on the link below!

https://forms.gle/4L4A2de4WgmJbJkg9

The survey will be up for 14 days. Please share this with your curl-using friends as well and ask them to contribute. This is our only and primary way to find out what users actually do with curl and what you want with it – and don’t want it to do!

The survey is hosted by Google forms. The curl project will not track users and we will not ask who you are (and than some general details to get a picture of curl users in general).

The analysis from the 2019 survey is available.

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2020/05/18/help-curl-the-user-survey-2020/

|

|

Marco Zehe: The focus of this blog is changing |

Recently, Mozilla introduced an official blog about all things accessibility. This blog is transitioning to a pure personal journal.

For years, this blog was a mixed bag between information about my official work at Mozilla and my personal views on accessibility. Now that Mozilla has its own accessibility blog, my personal blog at this space will contain less work-related material and more personal views on the broader subject of accessibility. I am also co-authoring the Mozilla accessibility blog, and will continue to inform the community about our work there. But this blog here will no longer receive such updates unless I find something personally noteworthy.

So, if you continue to follow this blog, I promise no duplicated content. If you are interested about what‘s happening at Mozilla, the new official source is linked above, and it also has an RSS feed to follow along.

https://marcozehe.de/2020/05/17/the-focus-of-this-blog-is-changing/

|

|

Без заголовка |

This week (no pun intended), the IndieWeb community’s “This Week in the IndieWeb” turned 6!

First published on 2014-05-12, the newsletter started as a fully-automatically generated weekly summary of activity on the IndieWeb’s community wiki: a list of edited and new pages, followed by the full content of the new pages, and then the recent edit histories of pages changed that week.

Since then the Newsletter has grown to include photos from recent events, the list of upcoming events, recent posts about the IndieWeb syndicated to the IndieNews aggregator, new community members (and their User pages), and a greatly simplified design of new & changed pages.

You can subscribe to the newsletter via email, RSS, or h-feed in your favorite Reader.

This week we also celebrated:

- 6 years of WithKnown

- 5 years of IndieWebCamps in D"usseldorf

See the Timeline page for more significant events in IndieWeb community history.

|

|

Armen Zambrano: Treeherder developer ergonomics |

In the last few months I’ve worked with contributors who wanted to be selected to work on Treeherder during this year’s Google Summer of Code. The initial proposal was to improve various Treeherder developer ergonomics (read: make Treeherder development easier). I’ve had three very active contributors that have helped to make a big difference (in alphabetical order): Shubham, Shubhank and Suyash.

In this post I would like to thank them publicly for all the work they have accomplished as well as list some of what has been accomplished. There’s also listed some work from Kyle who tackled the initial work of allowing normal Python development outside of Docker (more about this later).

After all, I won’t be participating in GSoC due to burn-out and because this project is mostly completed (thanks to our contributors!). Nevertheless, two of the contributors managed to get selected to help with Treeherder (Suyash) and Firefox Accounts (Shubham) for GSoC. Congratulations!

Some of the developer ergonomics improvements that landed this year are:

- Support running Treeherder & tests outside of Docker. Thanks to Kyle we can now set up a Python virtualenv outside of Docker and interact with all dependent services (mysql, redis and rabbitmq). This is incredibly useful to run tests and the backend code outside of Docker and to help your IDE install all Python packages in order to better analyze and integrate with your code (e.g., add breakpoints from your IDE). See PR here.

- Support manual ingestion of data. Before, you could only ingest data when you would set up the Pulse ingestion. This mean that you could only ingest real-time data (and all of it!) and you could not ingest data from the past. Now, you can ingest pushes, tasks and even Github PRs. See documentation.

- Add pre-commit hooks to catch linting issues. Prior to this, linting issues would require you to remember to run a script with all the linters or Travis to let you know. You can now get the linters to execute automatically on modified files (instead of all files in the repo), shortening the linting-feedback cycle. See hooks in pre-commit file

- Use Poetry to generate the docs. Serving locally the Treeherder docs is now as simple as running “poetry install && poetry run mkdocs serve.” No more spinning up Docker containers or creating and activating virtualenvs. We also get to introduce Poetry as a modern dependency and virtualenv manager. See code in pyproject.toml file

- Automatic syntax formatting. The black pre-commit hook now formats files that the developer touches. No need to fix the syntax after Travis fails with linting issues.

- Ability to run the same tests as Travis locally. In order to reduce differences between what Travis tests remotely and what we test locally, we introduced tox. The Travis code simplifies, the tox code can even automate starting the Docker containers and it removed a bash script that was trying to do what tox does (Windows users cannot execute bash scripts).

- Share Pulse credentials with random queue names. In the past we required users to set up an account with Pulse Guardian and generate their own PULSE_URL in order to ingest data. Last year, Dustin gave me the idea that we can share Pulse credentials; however, each consumer must ingest from dynamically generated queue names. This was initially added to support Heroku Review Apps, however, this works as well for local consumers. This means that a developer ingesting data would not be taking away Pulse messages from the queue of another developer.

- Automatically delete Pulse queues. Since we started using shared credentials with random queue names, every time a developer started ingesting data locally it would leave some queues behind in Pulse. When the local consumers stopped, these queues would overgrow and send my team and I alerts about it. With this change, the queues would automatically be destroyed when the consumers ceased to consume.

- Docker set up to automatically ingest data. This is useful since ingesting data locally required various steps in order to make it work. Now, the Docker set up ingests data without manual intervention.

- Use pip-compile to generate requirement files with hashes. Before, when we needed to update or add a Python package, we also had to add the hashes manually. With pip-compile, we can generate the requirement files with all hashes and subdepencies automatically. You can see the documentation here.

There’s many more changes that got fixed by our contributors, however, I won’t cover all of them. You can see the complete list in here.

Thank you for reading this far and thanks again to our contributors for making development on Treeherder easier!

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Relaxing video series brings serenity to your day |

Sitting in front of a computer all day (and getting caught up in the never-ending bad news cycle) can be draining. And if you happen to be working from home, … Read more

The post Relaxing video series brings serenity to your day appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

|

|

The Rust Programming Language Blog: Five Years of Rust |

With all that's going on in the world you'd be forgiven for forgetting that as of today, it has been five years since we released 1.0! Rust has changed a lot these past five years, so we wanted to reflect back on all of our contributors' work since the stabilization of the language.

Rust is a general purpose programming language empowering everyone to build reliable and efficient software. Rust can be built to run anywhere in the stack, whether as the kernel for your operating system or your next web app. It is built entirely by an open and diverse community of individuals, primarily volunteers who generously donate their time and expertise to help make Rust what it is.

Major Changes since 1.0

2015

1.2 — Parallel Codegen: Compile time improvements are a large theme to every release of Rust, and it's hard to imagine that there was a short time where Rust had no parallel code generation at all.

1.3 — The Rustonomicon: Our first release of the fantastic "Rustonomicon", a book that explores Unsafe Rust and its surrounding topics and has become a great resource for anyone looking to learn and understand one of the hardest aspects of the language.

1.4 — Windows MSVC Tier 1 Support: The first tier 1 platform promotion was bringing native support for 64-bit Windows using the Microsoft Visual C++ toolchain (MSVC). Before 1.4 you needed to also have MinGW (a third party GNU environment) installed in order to use and compile your Rust programs. Rust's Windows support is one of the biggest improvements these past five years. Just recently Microsoft announced a public preview of their official Rust support for the WinRT API! Now it's easier than ever build top quality native and cross platform apps.

1.5 — Cargo Install: The addition of being able to build Rust binaries alongside cargo's pre-existing plugin support has given birth to an entire ecosystem of apps, utilities, and developer tools that the community has come to love and depend on. Quite a few of the commands cargo has today were first plugins that the community built and shared on crates.io!

2016

1.6 — Libcore: libcore is a subset of the standard library that only

contains APIs that don't require allocation or operating system level features.

The stabilization of libcore brought the ability to compile Rust with no allocation

or operating system dependency was one of the first major steps towards Rust's

support for embedded systems development.

1.10 — C ABI Dynamic Libraries: The cdylib crate type allows Rust to be

compiled as a C dynamic library, enabling you to embed your Rust projects in

any system that supports the C ABI. Some of Rust's biggest success stories

among users is being able to write a small critical part of their system in

Rust and seamlessly integrate in the larger codebase, and it's now easier

than ever.

1.12 — Cargo Workspaces: Workspaces allow you to organise multiple rust projects and share the same lockfile. Workspaces have been invaluable in building large multi-crate level projects.

1.13 — The Try Operator: The first major syntax addition was the ? or

the "Try" operator. The operator allows you to easily propagate your error

through your call stack. Previously you had to use the try! macro, which

required you to wrap the entire expression each time you encountered a result,

now you can easily chain methods with ? instead.

try!(try!(expression).method()); // Old

expression?.method()?; // New

1.14 — Rustup 1.0: Rustup is Rust's Toolchain manager, it allows you to seamlessly use any version of Rust or any of its tooling. What started as a humble shell script has become what the maintainers affectionately call a "chimera". Being able to provide first class compiler version management across Linux, macOS, Windows, and the dozens of target platforms would have been a myth just five years ago.

2017

1.15 — Derive Procedural Macros: Derive Macros allow you to create powerful

and extensive strongly typed APIs without all the boilerplate. This was the

first version of Rust you could use libraries like serde or diesel's

derive macros on stable.

1.17 — Rustbuild: One of the biggest improvements for our contributors to

the language was moving our build system from the initial make based system

to using cargo. This has opened up rust-lang/rust to being a lot easier for

members and newcomers alike to build and contribute to the project.

1.20 — Associated Constants: Previously constants could only be associated with a module. In 1.20 we stabilised associating constants on struct, enums, and importantly traits. Making it easier to add rich sets of preset values for types in your API, such as common IP addresses or interesting numbers.

2018

1.24 — Incremental Compilation: Before 1.24 when you made a change in your library rustc would have to re-compile all of the code. Now rustc is a lot smarter about caching as much as possible and only needing to re-generate what's needed.

1.26 — impl Trait: The addition of impl Trait gives you expressive

dynamic APIs with the benefits and performance of static dispatch.

1.28 — Global Allocators: Previously you were restricted to using the

allocator that rust provided. With the global allocator API you can now

customise your allocator to one that suits your needs. This was an important

step in enabling the creation of the alloc library, another subset of the

standard library containing only the parts of std that need an allocator like

Vec or String. Now it's easier than ever to use even more parts of the

standard library on a variety of systems.

1.31 — 2018 edition: The release of the 2018 edition was easily our biggest release since 1.0, adding a collection of syntax changes and improvements to writing Rust written in a completely backwards compatible fashion, allowing libraries built with different editions to seamlessly work together.

- Non-Lexical Lifetimes A huge improvement to Rust's borrow checker, allowing it to accept more verifiable safe code.

- Module System Improvements Large UX improvements to how we define and use modules.

- Const Functions Const functions allow you to run and evaluate Rust code at compile time.

- Rustfmt 1.0 A new code formatting tool built specifically for Rust.

- Clippy 1.0 Rust's linter for catching common mistakes. Clippy makes it a lot easier to make sure that your code is not only safe but correct.

- Rustfix With all the syntax changes, we knew we wanted to provide the

tooling to make the transition as easy as possible. Now when changes are

required to Rust's syntax they're just a

cargo fixaway from being resolved.

2019

1.34 — Alternative Crate Registries: As Rust is used more and more in production, there is a greater need to be able to host and use your projects in non-public spaces, while cargo has always allowed remote git dependencies, with Alternative Registries your organisation can easily build and share your own registry of crates that can be used in your projects like they were on crates.io.

1.39 — Async/Await: The stabilisation of the async/await keywords for handling Futures was one of the major milestones to making async programming in Rust a first class citizen. Even just six months after its release async programming in Rust has blossomed into a diverse and performant ecosystem.

2020

1.42 — Subslice patterns: While not the biggest change, the addition

of the .. (rest) pattern has been a long awaited quality of life

feature that greatly improves the expressivity of pattern matching

with slices.

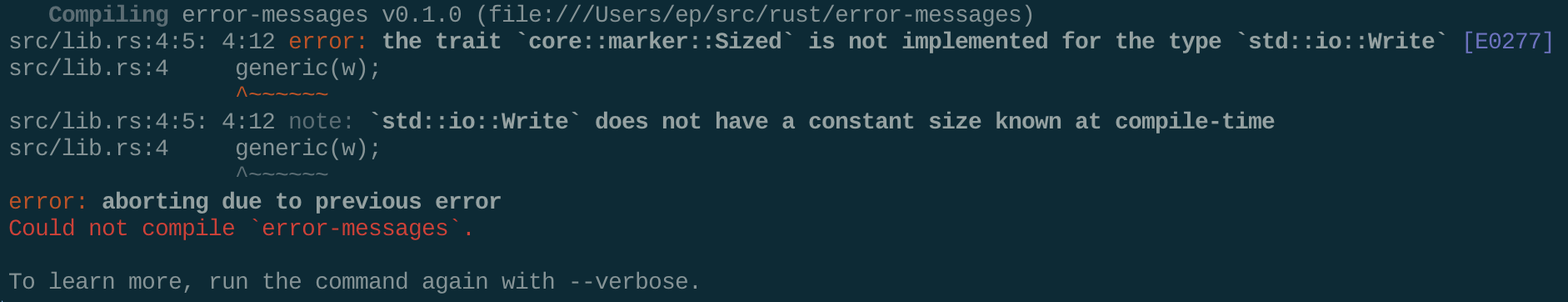

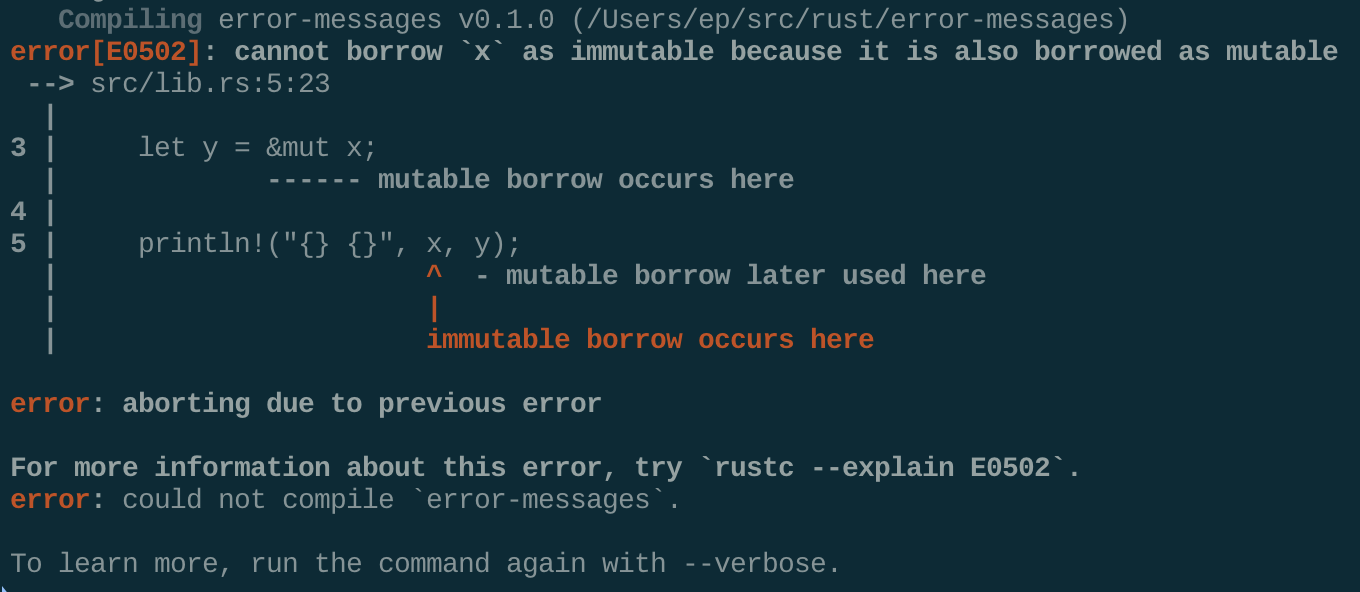

Error Diagnostics

One thing that we haven't mentioned much is how much Rust's error messages and diagnostics have improved since 1.0. Looking at older error messages now feels like looking at a different language.

We’ve highlighted a couple of examples that best showcase just how much we’ve improved showing users where they made mistakes and importantly help them understand why it doesn’t work and teach them how they can fix it.

First Example (Traits)

use std::io::Write;

fn trait_obj(w: &Write) {

generic(w);

}

fn generic(_w: &W) {}

Compiling error-messages v0.1.0 (file:///Users/usr/src/rust/error-messages)

src/lib.rs:6:5: 6:12 error: the trait `core::marker::Sized` is not implemented for the type `std::io::Write` [E0277]

src/lib.rs:6 generic(w);

^~~~~~~

src/lib.rs:6:5: 6:12 note: `std::io::Write` does not have a constant size known at compile-time

src/lib.rs:6 generic(w);

^~~~~~~

error: aborting due to previous error

Could not compile `error-messages`.

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

Compiling error-messages v0.1.0 (/Users/ep/src/rust/error-messages)

error[E0277]: the size for values of type `dyn std::io::Write` cannot be known at compilation time

--> src/lib.rs:6:13

|

6 | generic(w);

| ^ doesn't have a size known at compile-time

...

9 | fn generic(_w: &W) {}

| ------- - - help: consider relaxing the implicit `Sized` restriction: `+ ?Sized`

| |

| required by this bound in `generic`

|

= help: the trait `std::marker::Sized` is not implemented for `dyn std::io::Write`

= note: to learn more, visit /doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch19-04-advanced-types.html#dynamically-sized-types-and-the-sized-trait>

error: aborting due to previous error

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0277`.

error: could not compile `error-messages`.

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

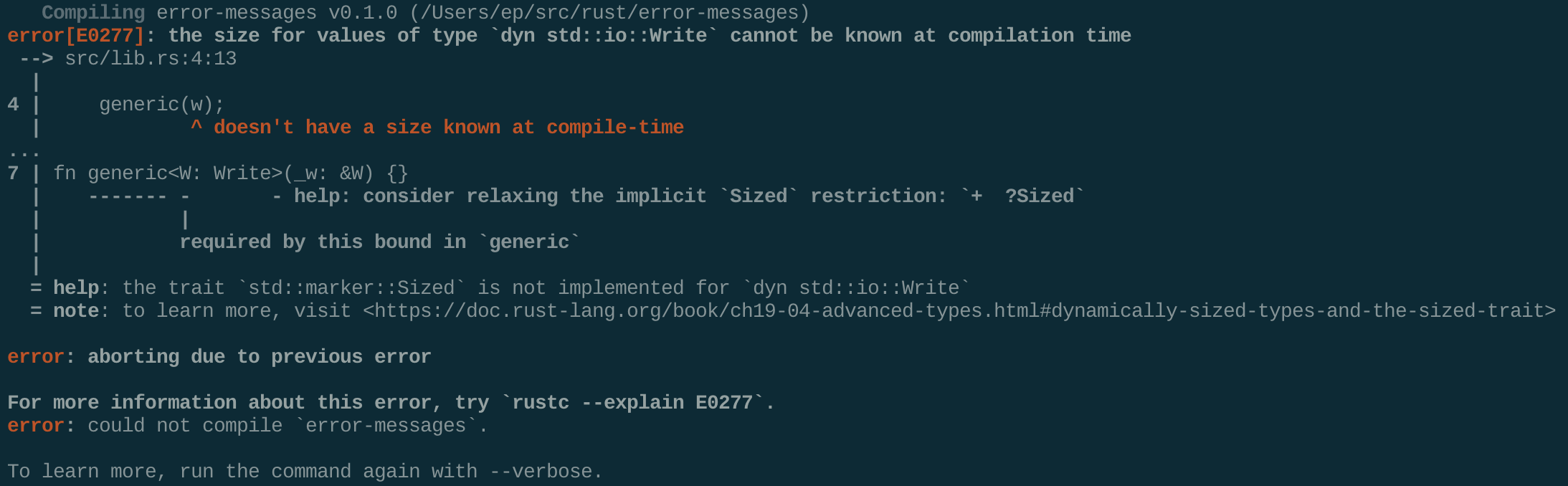

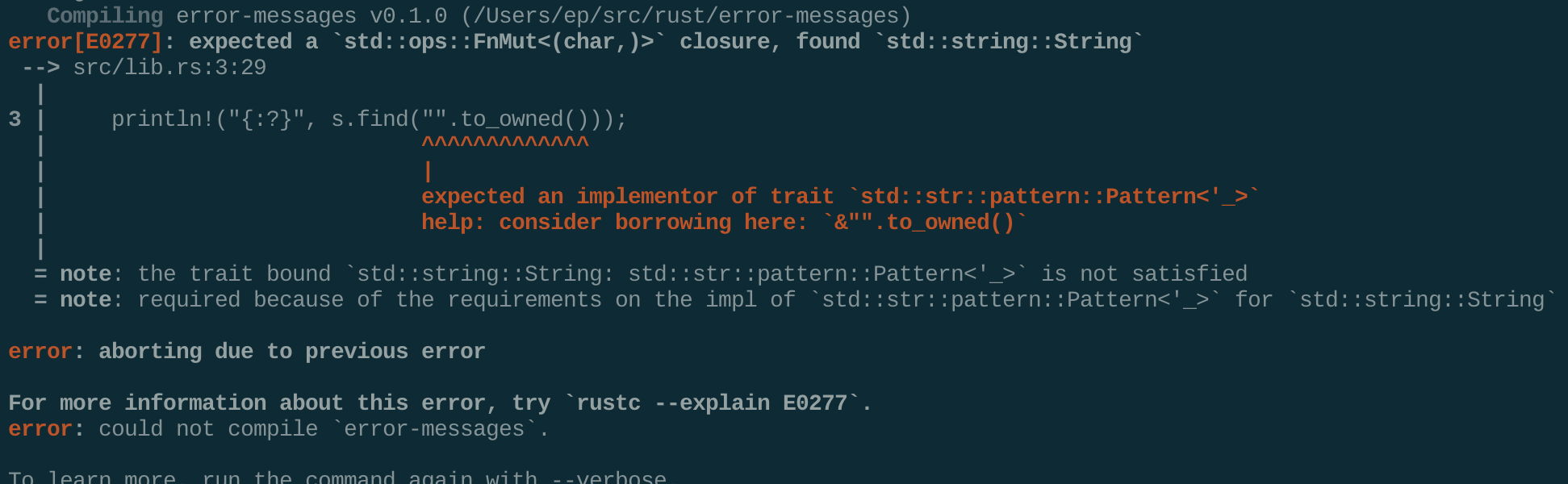

Second Example (help)

fn main() {

let s = "".to_owned();

println!("{:?}", s.find("".to_owned()));

}

Compiling error-messages v0.1.0 (file:///Users/ep/src/rust/error-messages)

src/lib.rs:3:24: 3:43 error: the trait `core::ops::FnMut<(char,)>` is not implemented for the type `collections::string::String` [E0277]

src/lib.rs:3 println!("{:?}", s.find("".to_owned()));

^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

note: in expansion of format_args!

:2:25: 2:56 note: expansion site

:1:1: 2:62 note: in expansion of print!

:3:1: 3:54 note: expansion site

:1:1: 3:58 note: in expansion of println!

src/lib.rs:3:5: 3:45 note: expansion site

src/lib.rs:3:24: 3:43 error: the trait `core::ops::FnOnce<(char,)>` is not implemented for the type `collections::string::String` [E0277]

src/lib.rs:3 println!("{:?}", s.find("".to_owned()));

^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

note: in expansion of format_args!

:2:25: 2:56 note: expansion site

:1:1: 2:62 note: in expansion of print!

:3:1: 3:54 note: expansion site

:1:1: 3:58 note: in expansion of println!

src/lib.rs:3:5: 3:45 note: expansion site

error: aborting due to 2 previous errors

Could not compile `error-messages`.

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

Compiling error-messages v0.1.0 (/Users/ep/src/rust/error-messages)

error[E0277]: expected a `std::ops::FnMut<(char,)>` closure, found `std::string::String`

--> src/lib.rs:3:29

|

3 | println!("{:?}", s.find("".to_owned()));

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^

| |

| expected an implementor of trait `std::str::pattern::Pattern<'_>`

| help: consider borrowing here: `&"".to_owned()`

|

= note: the trait bound `std::string::String: std::str::pattern::Pattern<'_>` is not satisfied

= note: required because of the requirements on the impl of `std::str::pattern::Pattern<'_>` for `std::string::String`

error: aborting due to previous error

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0277`.

error: could not compile `error-messages`.

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

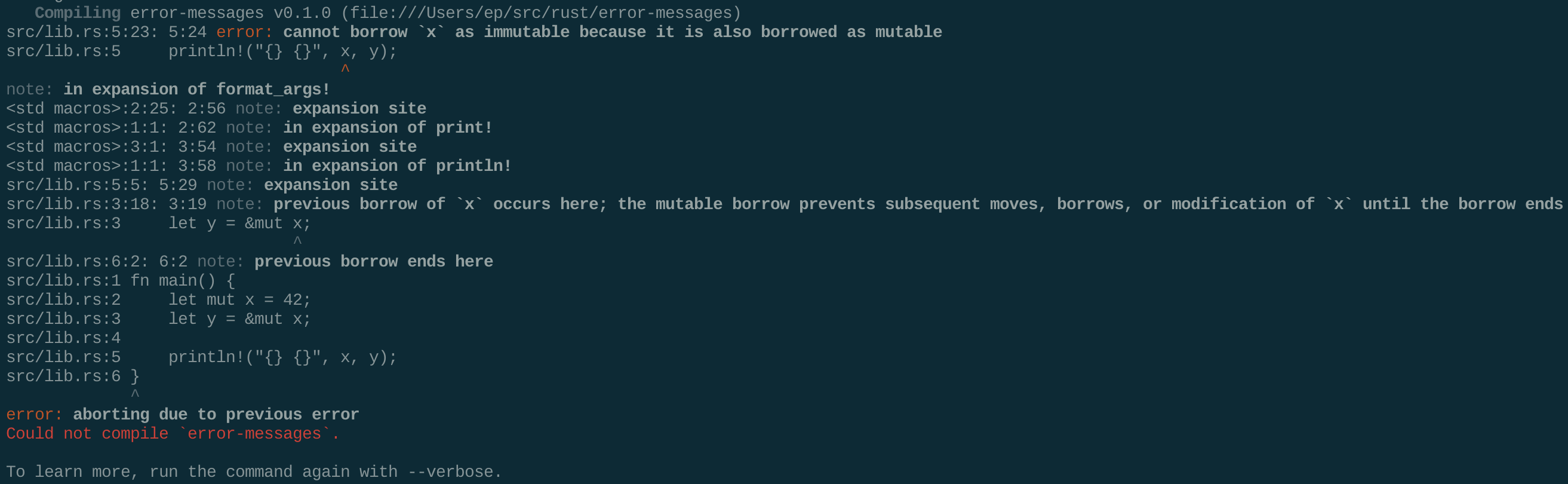

Third Example (Borrow checker)

fn main() {

let mut x = 7;

let y = &mut x;

println!("{} {}", x, y);

}

Compiling error-messages v0.1.0 (file:///Users/ep/src/rust/error-messages)

src/lib.rs:5:23: 5:24 error: cannot borrow `x` as immutable because it is also borrowed as mutable

src/lib.rs:5 println!("{} {}", x, y);

^

note: in expansion of format_args!

:2:25: 2:56 note: expansion site

:1:1: 2:62 note: in expansion of print!

:3:1: 3:54 note: expansion site

:1:1: 3:58 note: in expansion of println!

src/lib.rs:5:5: 5:29 note: expansion site

src/lib.rs:3:18: 3:19 note: previous borrow of `x` occurs here; the mutable borrow prevents subsequent moves, borrows, or modification of `x` until the borrow ends

src/lib.rs:3 let y = &mut x;

^

src/lib.rs:6:2: 6:2 note: previous borrow ends here

src/lib.rs:1 fn main() {

src/lib.rs:2 let mut x = 7;

src/lib.rs:3 let y = &mut x;

src/lib.rs:4

src/lib.rs:5 println!("{} {}", x, y);

src/lib.rs:6 }

^

error: aborting due to previous error

Could not compile `error-messages`.

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

Compiling error-messages v0.1.0 (/Users/ep/src/rust/error-messages)

error[E0502]: cannot borrow `x` as immutable because it is also borrowed as mutable

--> src/lib.rs:5:23

|

3 | let y = &mut x;

| ------ mutable borrow occurs here

4 |

5 | println!("{} {}", x, y);

| ^ - mutable borrow later used here

| |

| immutable borrow occurs here

error: aborting due to previous error

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0502`.

error: could not compile `error-messages`.

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

Quotes from the teams

Of course we can't cover every change that has happened. So we reached out and asked some of our teams what changes they are most proud of:

For rustdoc, the big things were:

- The automatically generated documentation for blanket implementations

- The search itself and its optimizations (last one being to convert it into JSON)

- The possibility to test more accurately doc code blocks "compile_fail, should_panic, allow_fail"

- Doc tests are now generated as their own seperate binaries.

— Guillaume Gomez (rustdoc)

Rust now has baseline IDE support! Between IntelliJ Rust, RLS and rust-analyzer, I feel that most users should be able to find "not horrible" experience for their editor of choice. Five years ago, "writing Rust" meant using old school Vim/Emacs setup.

— Aleksey Kladov (IDEs and editors)

For me that would be: Adding first class support for popular embedded architectures and achieving a striving ecosystem to make micro controller development with Rust an easy and safe, yet fun experience.

— Daniel Egger (Embedded WG)

The release team has only been around since (roughly) early 2018, but even in that time, we've landed ~40000 commits just in rust-lang/rust without any significant regressions in stable.

Considering how quickly we're improving the compiler and standard libraries, I think that's really impressive (though of course the release team is not the sole contributor here). Overall, I've found that the release team has done an excellent job of managing to scale to the increasing traffic on issue trackers, PRs being filed, etc.

— Mark Rousskov (Release)

Within the last 3 years we managed to turn Miri from an experimental interpreter into a practical tool for exploring language design and finding bugs in real code—a great combination of PL theory and practice. On the theoretical side we have Stacked Borrows, the most concrete proposal for a Rust aliasing model so far. On the practical side, while initially only a few key libraries were checked in Miri by us, recently we saw a great uptake of people using Miri to find and fix bugs in their own crates and dependencies, and a similar uptake in contributors improving Miri e.g. by adding support for file system access, unwinding, and concurrency.

— Ralf Jung (Miri)

If I had to pick one thing I'm most proud of, it was the work on non-lexical lifetimes (NLL). It's not only because I think it made a big difference in the usability of Rust, but also because of the way that we implemented it by forming the NLL working group. This working group brought in a lot of great contributors, many of whom are still working on the compiler today. Open source at its best!

— Niko Matsakis (Language)

The Community

As the language has changed and grown a lot in these past five years so has its community. There's been so many great projects written in Rust, and Rust's presence in production has grown exponentially. We wanted to share some statistics on just how much Rust has grown.

- Rust has been voted "Most Loved Programming Language" every year in the past four Stack Overflow developer surveys since it went 1.0.

- We have served over 2.25 Petabytes (1PB = 1,000 TB) of different versions of the compiler, tooling, and documentation this year alone!

- In the same time we have served over 170TB of crates to roughly 1.8 billion requests on crates.io, doubling the monthly traffic compared to last year.

When Rust turned 1.0 you could count the number of companies that were using it in production on one hand. Today, it is being used by hundreds of tech companies with some of the largest tech companies such as Apple, Amazon, Dropbox, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft choosing to use Rust for its performance, reliability, and productivity in their projects.

Conclusion

Obviously we couldn't cover every change or improvement to Rust that's happened since 2015. What have been your favourite changes or new favourite Rust projects? Feel free to post your answer and discussion on our Discourse forum.

Lastly, we wanted to thank everyone who has to contributed to the Rust, whether you contributed a new feature or fixed a typo, your work has made Rust the amazing project it is today. We can't wait to see how Rust and its community will continue to grow and change, and see what you all will build with Rust in the coming decade!

https://blog.rust-lang.org/2020/05/15/five-years-of-rust.html

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Request for comment: how to collaboratively make trustworthy AI a reality |

A little over a year ago, I wrote the first of many posts arguing: if we want a healthy internet — and a healthy digital society — we need to make sure AI is trustworthy. AI, and the large pools of data that fuel it, are central to how computing works today. If we want apps, social networks, online stores and digital government to serve us as people — and as citizens — we need to make sure the way we build with AI has things like privacy and fairness built in from the get go.

Since writing that post, a number of us at Mozilla — along with literally hundreds of partners and collaborators — have been exploring the questions: What do we really mean by ‘trustworthy AI’? And, what do we want to do about it?

How do we collaboratively make trustworthy AI a reality?

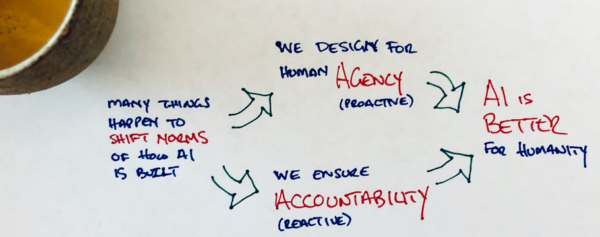

Today, we’re kicking off a request for comment on v0.9 of Mozilla’s Trustworthy AI Whitepaper — and on the accompanying theory of change diagram that outlines the things we think need to happen. While I have fallen out of the habit, I have traditionally included a simple diagram in my blog posts to explain the core concept I’m trying to get at. I would like to come back to that old tradition here:

This cartoonish drawing gets to the essence of where we landed in our year of exploration: ‘agency’ and ‘accountability’ are the two things we need to focus on if we want the AI that surrounds us everyday to be more trustworthy. Agency is something that we need to proactively build into the digital products and services we use — we need computing norms and tech building blocks that put agency at the forefront of our design process. Accountability is about having effective ways to react if things go wrong — ways for people to demand better from the digital products and services we use everyday and for governments to enforce rules when things go wrong. Of course, I encourage you to look at the full (and fancy) version of our theory of change diagram — but the fact that ‘agency’ (proactive) and ‘accountability’ (reactive) are the core, mutually reinforcing parts of our trustworthy AI vision is the key thing to understand.

In parallel to developing our theory of change, Mozilla has also been working closely with partners over the past year to show what we mean by trustworthy AI, especially as it relates to consumer internet technology. A significant portion of our 2019 Internet Health Report was dedicated to AI issues. We ran campaigns to: pressure platforms like YouTube to make sure their content recommendations don’t promote misinformation; and call on Facebook and others to open up APIs to make political ad targeting more transparent. We provided consumers with a critical buying guide for AI-centric smart home gadgets like Amazon Alexa. We invested ~$4M in art projects and awarded fellowships to explore AI’s impact on society. And, as the world faced a near universal health crisis, we asked questions about how issues like AI, big data and privacy will play during — and after — the pandemic. As with all of Mozilla’s movement building work, our intention with our trustworthy AI efforts is to bias towards action and working with others.

A request for comments

It’s with this ‘act + collaborate’ bias in mind that we are embarking on a request for comments on v0.9 of the Mozilla Trustworthy AI Whitepaper. The paper talks about how industry, regulators and citizens of the internet can work together to build more agency and accountability into our digital world. It also talks briefly about some of the areas where Mozilla will focus, knowing that Mozilla is only one small actor in the bigger picture of shifting the AI tide.

Our aim is to use the current version of this paper as a foil for improving our thinking and — even more so — for identifying further opportunities to collaborate with others in building more trustworthy AI. This is why we’re using the term ‘request for comment’ (RFC). It is a very intentional hat tip to a long standing internet tradition of collaborating openly to figure out how things should work. For decades, the RFC process has been used by the internet community to figure out everything from standards for sharing email across different computer networks to best practices for defeating denial of service attacks. While this trustworthy AI effort is not primarily about technical standards (although that’s part of it), it felt (poetically) useful to frame this process as an RFC aimed at collaboratively and openly figuring out how to get to a world where AI and big data work quite differently than they do today.

We’re imagining that Mozilla’s trustworthy AI request for comment process includes three main steps, with the first step starting today.

Step 1: partners, friends and critics comment on the white paper

During this first part of the RFC, we’re interested in: feedback on our thinking; further examples to flesh out our points, especially from sources outside Europe and North America; and ideas for concrete collaboration.

The best way to provide input during this part of the process is to put up a blog post or some other document reacting to what we’ve written (and then share it with us). This will give you the space to flesh out your ideas and get them in front of both Mozilla (send us your post!) and a broader audience. If you want something quicker, there is also an online form where you can provide comments. We’ll be holding a number of online briefings and town halls for people who want to learn about and comment on the content in the paper — sign up through the form above to find out more. This phase of the process starts today and will run through September 2020.

Step 2: collaboratively map what’s happening — and what should happen

Given our focus on action, mapping out real trustworthy AI work that is already happening — and that should happen — is even more critical than honing frameworks in the white paper. At a baseline, this means collecting information about educational programs, technology building blocks, product prototypes, consumer campaigns and emerging government policies that focus on making trustworthy AI a reality.

The idea is that the ‘maps’ we create will be a resource for both Mozilla and the broader field. They will help Mozilla direct its fellows, funding and publicity efforts to valuable projects. And, they will help people from across the field see each other so they can share ideas and collaborate completely independently of our work.

Process-wise, these maps will be developed collaboratively by Mozilla’s Insights Team with involvement of people and organizations from across the field. Using a mix of feedback from the white paper comment process (step 1) and direct research, they will develop a general map of who is working on key elements of trustworthy AI. They will also develop a deeper landscape analysis on the topic of data stewardship and alternative approaches to data governance. This work will take place from now until November 2020.

Step 3: do more things together, and update the paper

The final — and most important — part of the process will be to figure out where Mozilla can do more to support and collaborate with others. We already know that we want to work more with people who are developing new approaches to data stewardship, including trusts, commons and coops. We see efforts like these as foundational building blocks for trustworthy AI. Separately, we also know that we want to find ways to support African entrepreneurs, researchers and activists working to build out a vision of AI for that continent that is independent of the big tech players in the US and China. Through the RFC process, we hope to identify further areas for action and collaboration, both big and small.

Partnerships around data stewardship and AI in Africa are already being developed by teams within Mozilla. A team has also been tasked with identifying smaller collaborations that could grow into something bigger over the coming years. We imagine this will happen slowly through suggestions made and patterns identified during the RFC process. This will then shape our 2021 planning — and will feed back into a (hopefully much richer) v1.0 of the whitepaper. We expect all this to be done by the end of 2020.

Mozilla cannot do this alone. None of us can.

As noted above: the task at hand is to collaboratively and openly figure out how to get to a world where AI and big data work quite differently than they do today. Mozilla cannot do this alone. None of us can. But together we are much greater than the sum of our parts. While this RFC process will certainly help us refine Mozilla’s approach and direction, it will hopefully also help others figure out where they want to take their efforts. And, where we can work together. We want our allies and our community not only to weigh in on the white paper, but also to contribute to the collective conversation about how we reshape AI in a way that lets us build — and live in — a healthier digital world.

PS. A huge thank you to all of those who have collaborated with us thus far and who will continue to provide valuable perspectives to our thinking on AI.

The post Request for comment: how to collaboratively make trustworthy AI a reality appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: How to overcome distractions (and be more productive) |

Distractions tempt us at every turn, from an ever-growing library of Netflix titles to video games (Animal Crossing is my current vice) to all of the other far more tantalizing … Read more

The post How to overcome distractions (and be more productive) appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

|

|

David Bryant: A Quantum Leap for the Web |

Over the past year, our top priority for Firefox was the Electrolysis project to deliver a multi-process browsing experience to users. Running Firefox in multiple processes greatly improves security and performance. This is the largest change we’ve ever made to Firefox, and we’ll be rolling out the first stage of Electrolysis to 100% of Firefox desktop users over the next few months.

But, that doesn’t mean we’re all out of ideas in terms of how to improve performance and security. In fact, Electrolysis has just set us up to do something we think will be really big.

We’re calling it Project Quantum.

Quantum is our effort to develop Mozilla’s next-generation web engine and start delivering major improvements to users by the end of 2017. If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of a web engine, it’s the core of the browser that runs all the content you receive as you browse the web. Quantum is all about making extensive use of parallelism and fully exploiting modern hardware. Quantum has a number of components, including several adopted from the Servo project.

The resulting engine will power a fast and smooth user experience on both mobile and desktop operating systems — creating a “quantum leap” in performance. What does that mean? We are striving for performance gains from Quantum that will be so noticeable that your entire web experience will feel different. Pages will load faster, and scrolling will be silky smooth. Animations and interactive apps will respond instantly, and be able to handle more intensive content while holding consistent frame rates. And the content most important to you will automatically get the highest priority, focusing processing power where you need it the most.

So how will we achieve all this?

Web browsers first appeared in the era of desktop PCs. Those early computers only had single-core CPUs that could only process commands in a single stream, so they truly could only do one thing at a time. Even today, in most browsers an individual web page runs primarily on a single thread on a single core.

But nowadays we browse the web on phones, tablets, and laptops that have much more sophisticated processors, often with two, four or even more cores. Additionally, it’s now commonplace for devices to incorporate one or more high-performance GPUs that can accelerate rendering and other kinds of computations.

One other big thing that has changed over the past fifteen years is that the web has evolved from a collection of hyperlinked static documents to a constellation of rich, interactive apps. Developers want to build, and consumers expect, experiences with zero latency, rich animations, and real-time interactivity. To make this possible we need a web platform that allows developers to tap into the full power of the underlying device, without having to agonize about the complexities that come with parallelism and specialized hardware.

And so, Project Quantum is about developing a next-generation engine that will meet the demands of tomorrow’s web by taking full advantage of all the processing power in your modern devices. Quantum starts from Gecko, and replaces major engine components that will benefit most from parallelization, or from offloading to the GPU. One key part of our strategy is to incorporate groundbreaking components of Servo, an independent, community-based web engine sponsored by Mozilla. Initially, Quantum will share a couple of components with Servo, but as the projects evolve we will experiment with adopting even more.

A number of the Quantum components are written in Rust. If you’re not familiar with Rust, it’s a systems programming language that runs blazing fast, while simplifying development of parallel programs by guaranteeing thread and memory safety. In most cases, Rust code won’t even compile unless it is safe.

We’re taking on a lot of separate but related initiatives as part of Quantum, and we’re revisiting many old assumptions and implementations. The high-level approach is to rethink many fundamental aspects of how a browser engine works. We’ll be re-engineering foundational building blocks, like how we apply CSS styles, how we execute DOM operations, and how we render graphics to your screen.

Quantum is an ambitious project, but users won’t have to wait long to start seeing improvements roll out. We’re going to ship major improvements next year, and we’ll iterate from there. A first version of our new engine will ship on Android, Windows, Mac, and Linux. Someday we hope to offer this new engine for iOS, too.

We’re confident Quantum will deliver significantly improved performance. If you’re a developer and you’d like to get involved, you can learn more about Quantum on the the Mozilla wiki, and explore ways that you can contribute. We hope you’ll take the Quantum leap with us.

Special thanks to Ryan Pollock for contributing to this post.

A Quantum Leap for the Web was originally published in Mozilla Tech on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

David Bryant: Why WebAssembly is a game changer for the web — and a source of pride for Mozilla and Firefox |

With today’s release of Firefox, we are the first browser to support WebAssembly. If you haven’t yet heard of WebAssembly, it’s an emerging standard inspired by our research to enable near-native performance for web applications.

WebAssembly is one of the biggest advances to the Web Platform over the past decade.

This new standard will enable amazing video games and high-performance web apps for things like computer-aided design, video and image editing, and scientific visualization. Over time, many existing productivity apps (e.g. email, social networks, word processing) and JavaScript frameworks will likely use WebAssembly to significantly reduce load times while simultaneously improving performance while running. Unlike other approaches that have required plug-ins to achieve near-native performance in the browser, WebAssembly runs entirely within the Web Platform. This means that developers can integrate WebAssembly libraries for CPU-intensive calculations (e.g. compression, face detection, physics) into existing web apps that use JavaScript for less intensive work.

To get a quick understanding of WebAssembly, and to get an idea of how some companies are looking at using it, check out this video. You’ll hear from engineers at Mozilla, and partners such as Autodesk, Epic, and Unity.

https://medium.com/media/1858e816355bfa288aa7294e39278e67/hrefIt’s been a long, winding, and exciting road getting here.

JavaScript was originally intended as a lightweight language for fairly simple scripts. It needed to be easy for novice developers to code in. You know — for relatively simple things like making sure that you fill out a form correctly when you submit it.

A lot has changed since then. Modern web apps are complex computer programs, with client and server code, much of it written in JavaScript.

But, for all the advances in the JavaScript programming language and the engines that run it (including Mozilla’s SpiderMonkey engine), JavaScript still has inherent limitations that make it a poor fit for some scenarios. Most notably, when a browser actually executes JavaScript it typically can’t run the program as fast as the operating system can run a comparable native program written in other programming languages.

We’ve always been well aware of this at Mozilla but that has never limited our ambitions for the web. So a few years ago we embarked on a research project — to build a true virtual machine in the browser that would be capable of safely running both JavaScript and high-speed languages at near-native speeds. In particular we set a goal to allow modern video games to run in Firefox without plug-ins, knowing the Web Platform would then be able to run nearly any kind of application. Our first major step, after a great deal of experimentation, was to demonstrate that games built upon popular game engines could run in Firefox using an exploratory low-level subset of JavaScript called asm.js.

The asm.js sub-language worked impressively well, and we knew the approach could work even better as a first-class web standard. So, using asm.js as a proof of concept, we set out to collaborate with other browser makers to establish such a standard that could run as part of browsers. Together with expert engineers across browser makers, we established consensus on WebAssembly. We expect support for it will soon start shipping in other browsers.

Web apps written with WebAssembly can run at near-native speeds because, unlike JavaScript, all the code a programmer writes is parsed and compiled ahead of time before reaching the browser. The browser then just sees low-level, machine-ready instructions it can quickly validate, optimize, and run.

In some ways, WebAssembly changes what it means to be a web developer, as well as the fundamental abilities of the web. With WebAssembly and an accompanying set of tools, programs written in languages like C/C++ can be ported to the web so they run with near-native performance. We expect that, as WebAssembly continues to evolve, you’ll also be able to use it with programming languages often used for mobile apps, like Java, Swift, and C#.

If you’re interested in hearing more about the backstory of WebAssembly, check out this behind-the-scenes look.

https://medium.com/media/7f594db82cecacb4cffaac7932ae1ac9/hrefWebAssembly is shipping today in Firefox on Windows, MacOS, Linux, and Android. We’re particularly excited about the potential on mobile — do all those apps really need to be native?

If you’d like to try out some applications that use WebAssembly, upgrade to Firefox 52, and check out this demo of Zen Garden by Epic. For your convenience, we’ve embedded a video of the demo below.

https://medium.com/media/9c771666d7a80886c78da81479420ee7/hrefIf you’re a developer interested in working with WebAssembly, check out WebAssembly documentation on MDN. You might also want to see this series of blog posts by Lin Clark that explain WebAssembly through some cool cartoons.

Here at Mozilla we’re focused on moving the web forward and on making Firefox the best browser, hands down. With WebAssembly shipping today and Project Quantum well underway, we’re more bullish about the web — and about Firefox — than ever.

Special thanks to Ryan Pollock for contributing to this post.