Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: TLS 1.0 and 1.1 Removal Update |

tl;dr Enable support for Transport Layer Security (TLS) 1.2 today!

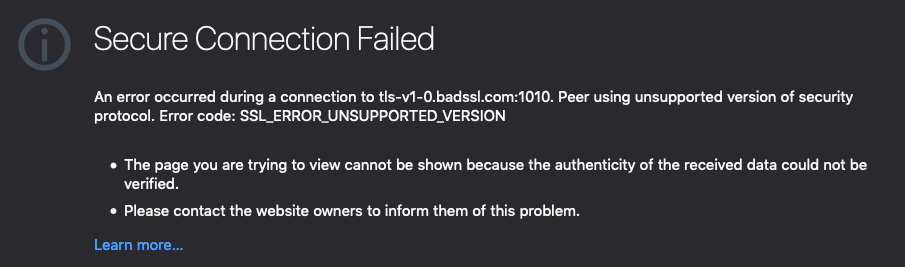

As you may have read last year in the original announcement posts, Safari, Firefox, Edge and Chrome are removing support for TLS 1.0 and 1.1 in March of 2020. If you manage websites, this means there’s less than a year to enable TLS 1.2 (and, ideally, 1.3) on your servers, otherwise all major browsers will display error pages, rather than the content your users were expecting to find.

In this article we provide some resources to check your sites’ readiness, and start planning for a TLS 1.2+ world in 2020.

Check the TLS “Carnage” list

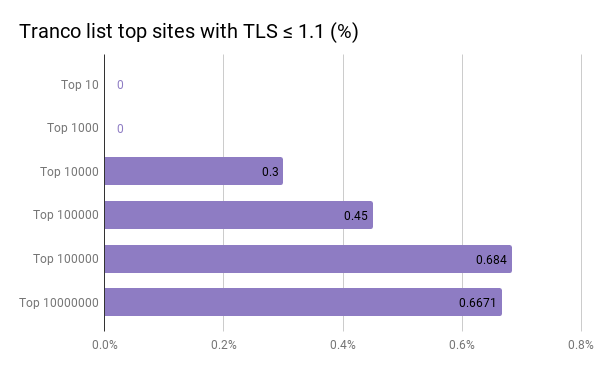

Once a week, the Mozilla Security team runs a scan on the Tranco list (a research-focused top sites list) and generates a list of sites still speaking TLS 1.0 or 1.1, without supporting TLS >= 1.2.

As of this week, there are just over 8,000 affected sites from the one million listed by Tranco.

There are a few potential gotchas to be aware of, if you do find your site on this list:

- 4% of the sites are using TLS <= 1.1 to redirect from a bare domain (https://example.com) to www (https://www.example.com) on TLS >= 1.2 (or vice versa). If you were to only check your site post-redirect, you might miss a potential footgun.

- 2% of the sites don’t redirect from bare to www (or vice versa), but do support TLS >= 1.2 on one of them.

The vast majority (94%), however, are just bad—it’s TLS <= 1.1 everywhere.

If you find that a site you work on is in the TLS “Carnage” list, you need to come up with a plan for enabling TLS 1.2 (and 1.3, if possible). However, this list only covers 1 million sites. Depending on how popular your site is, you might have some work to do regardless of whether you’re not listed by Tranco.

Run an online test

Even if you’re not on the “Carnage” list, it’s a good idea to test your servers all the same. There are a number of online services that will do some form of TLS version testing for you, but only a few will flag not supporting modern TLS versions in an obvious way. We recommend using one or more of the following:

- Hardenize will fail your site if it doesn’t support TLS 1.2.

- ImmuniWeb will indicate old versions of TLS as violations of PCI DSS requirements.

- Qualys’ SSL Server Test will penalize you if TLS 1.2 is not currently supported.

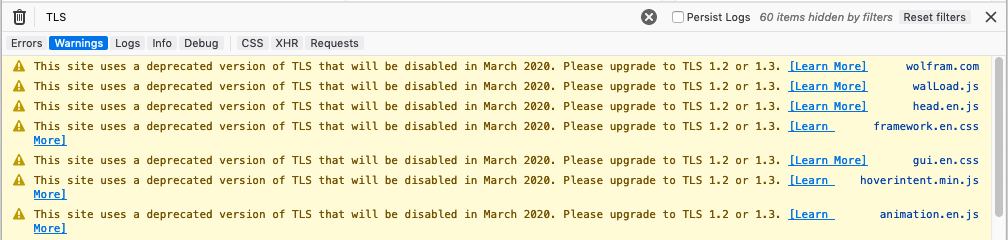

Check developer tools

Another way to do this is open up Firefox (versions 68+) or Chrome (versions 72+) DevTools, and look for the following warnings in the console as you navigate around your site.

What’s Next?

This October, we plan on disabling old TLS in Firefox Nightly and you can expect the same for Chrome and Edge Canaries. We hope this will give enough time for sites to upgrade before affecting their release population users.

The post TLS 1.0 and 1.1 Removal Update appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/05/tls-1-0-and-1-1-removal-update/

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: ZombieLoad doesn't affect Power Macs |

The attackers don't have control over the observed address, so they can't easily read arbitrary memory, but careful scanning for the type of data you're targeting can still make the attack effective even against the OS kernel. For example, since URLs can be picked out of memory, this apparent proof of concept shows a separate process running on the same CPU victimizing Firefox to extract the URL as the user types it in. This works because as the user types, the values of the individual keystrokes go through the LFB to the L1 cache, allowing the malicious process to observe the changes and extract characters. There is much less data available to the attacking process but that also means there is less to scan, making real-time attacks like this more feasible.

That said, because the attack is specific to architectural details of HT (and the authors of the attack say they even tried on other SMT CPUs without success), this particular exploit wouldn't work even against modern high-SMT count Power CPUs like POWER9. It certainly won't work against a Power Mac because no Power Mac CPU ever implemented SMT, not even the G5. While Mozilla is deploying a macOS-specific fix, we don't need it in TenFourFox, nor do we need other mitigations. It's especially bad news for Intel because nearly every Intel chip since 2011 is apparently vulnerable and the performance impact of fixing ZombieLoad varies anywhere from Intel's Pollyanna estimate of 3-9% to up to 40% if HT must be disabled completely.

Is this a major concern for users? Not as such: although the attacks appear to be practical and feasible, they require you to run dodgy software and that's a bad idea on any platform because dodgy software has any number of better ways of pwning your computer. So don't run dodgy programs!

Meanwhile, TenFourFox FPR14 final should be available for testing this weekend.

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2019/05/zombieload-doesnt-affect-power-macs.html

|

|

Adrian Gaudebert: react-content-marker Released – Marking Content with React |

Last year, in a React side-project, I had to replace some content in a string with HTML markup. That is not a trivial thing to do with React, as you can't just put HTML as string in your content, unless you want to use dangerouslySetInnerHtml — which I don't. So, I hacked a little code to smartly split my string into an array of sub-strings and DOM elements.

More recently, while working on Translate.Next — the rewrite of Pontoon's translate page to React — I stumbled upon the same problem. After looking around the Web for a tool that would solve it, and coming up short handed, I decided to write my own and make it a library.

Introducing react-content-marker v1.0

react-content-marker is a library for React to mark content in a string based on rules. These rules can be simple strings or regular expressions. Let's look at an example.

Say you have a blob of text, and you want to make the numbers in that text more visible, for example by making them bold.

const content = 'The fellowship had 4 Hobbits but only 1 Dwarf.';

Matching numbers can be done with a simple regex: /(\d+)/. If we turn that into a parser:

const parser = {

rule: /(\d+)/,

tag: x => { x },

};

We can now use that parser to create a content marker, and use it to enhance our content:

import createMarker from 'react-content-marker'; const Marker = createMarker([parser]); render({ content } );

This will show:

The fellowship had 4 Hobbits but only 1 Dwarf.

Hurray!

Advanced usage

Passing parsers

The first thing to note is that you can pass any number of parsers to the createMarker function, and they will all be called in turn. The order of the parsers is very important though, because content that has already been marked will not be parsed again. Let's look at another example.

Say you have a rule that matches content between brackets: /({.*})/, and a rule that matches content between brackets that contain only capital letters: /({[A-W]+})/. Now let's say you are marking this content: I have {CATCOUNT} cats. Whichever rule you passed first will match the content between brackets, and the second rule will not apply. You thus need to make sure that your rules are ordered so that the most important ones come first. Generally, that means you want to have the more specific rules first.

The reason why this happens is that, behind the scene, the matched content is turned into a DOM element, and parsers ignore non-string content. With the previous example, the initial string, I have {CATCOUNT} cats, would be turned into ['I have ', <mark>{CATCOUNT}</mark>, ' cats'] after the first parser is called. The second one then only looks at 'I have ' and ' cats', which do not match.

Using regex

The second important thing to know relates to regex. You might have noticed that I put parentheses in my examples above: they are required for the algorithm to capture content. But that also gives you more flexibility: you can use a regex that matches some content that you do not want to mark. Let's say you want to match only the name of someone who's being greeted, with this rule: /hello (\w+)/i. Applying it to Hello Adrian will only mark the Adrian part of that content.

Sometimes, however, you need to use more complex regex that include several groups of parentheses. When that's the case, by default react-content-marker will mark the content of the last non-null capturing group. In such cases, you can add a matchIndex number to your parser: that index will be used to select the capture group to mark.

Here's a simple example:

const parser = {

rule: /(hello (world|folks))/i,

tag: x => { x },

};

Applying this rule to Hello World will show: Hello World. If we want to, instead, make the whole match bold, we'll have to use matchIndex:

const parser = {

rule: /(hello (world|folks))/i,

matchIndex: 0,

tag: x => { x },

};

Now our entire string will correctly be made bold: Hello World.

Advanced example

If you're interested in looking at an advanced usage example of this library, I recommend you check out how we use in Pontoon, Mozilla's localization platform. We have a long list of parsers there, and they have a lot of edge-cases.

Installation and stuff

react-content-marker is available on npm, so you can easily install it with your favorite javascript package manager:

npm install -D react-content-marker # or yarn add react-content-marker

The code is released under the BSD 3-Clause License, and is available on github. If you hit any problems with it, or have a use case that is not covered, please file an issue. And of course, you are always welcome to contribute a patch!

I hope this is useful to someone out there. It has been for me at least, on Pontoon and on several React-based side-projects. I like how flexible it is, and I believe it does more than any other similar tools I could find around the Web.

http://adrian.gaudebert.fr/blog/post/react-content-marker-released-marking-content-with-react

|

|

Mike Hoye: The Next Part Of The Process |

I’ve announced this upcoming change and the requirements we’ve laid out for a replacement service for IRC, but I haven’t widely discussed the evaluation process in any detail, including what you can expect it to look like, how you can participate, and what you can expect from me. I apologize for that, and really should have done so sooner.

Briefly, I’ll be drafting a template doc based on our stated requirements, and once that’s in good, markdowny shape we’ll be putting it on GitHub with preliminary information for each of the stacks we’re considering and opening it up to community discussion and participation.

From there, we’re going to be taking pull requests and assembling our formal understanding of each of the candidates. As well, we’ll be soliciting more general feedback and community impressions of the candidate stacks on Mozilla’s Community Discourse forum.

I’ll be making an effort to ferry any useful information on Discourse back to GitHub, which unfortunately presents some barriers to some members of our community.

While this won’t be quite the same as a typical RFC/RFP process – I expect the various vendors as well as members the Mozilla community to be involved – we’ll be taking a lot of cues from the Rust community’s hard-won knowledge about how to effectively run a public consultation process.

In particular, it’s critical to me that this process to be as open and transparent as possible, explicitly time-boxed, and respectful of the Mozilla Community Participation Guidelines (CPG). As I’ve mentioned before, accessibility and developer productivity will both weigh heavily on our evaluation process, and the Rust community’s “no new rationale” guidelines will be respected when it comes time to make the final decision.

When it kicks off, this step will be widely announced both inside and outside Mozilla.

As part of that process, our IT team will be standing up instances of each of the candidate stacks and putting them behind the Participation Systems team’s “Mozilla-IAM” auth system. We’ll be making them available to the Mozilla community at first, and expanding that to include Github and via-email login soon afterwards for broader community testing. Canonical links to these trial systems will be prominently displayed on the GitHub repository; as the line goes, accept no substitutes.

Some things to note: we will also be using this period to evaluate these tools from a community moderation and administration perspective as well, to make sure that we have the tools and process available to meaningfully uphold the CPG.

To put this somewhat more charitably than it might deserve, we expect that some degree of this testing will be a typical if unfortunate byproduct of the participative process. But we also have plans to automate some of that stress-testing, to test both platform API usability and the effectiveness of our moderation tools. Which I suppose is long-winded way of saying: you’ll probably see some robots in there play-acting at being jerks, and we’re going to ask you to play along and figure out how to flag them as bad actors so we can mitigate the jerks of the future.

As well, we’re going to be doing the usual whats-necessaries to avoid the temporary-permanence trap, and at the end of the evaluation period all the instances of our various candidates will be shut down and deleted.

Our schedule is still being sorted out, and I’ll have more about that and our list of candidates shortly.

http://exple.tive.org/blarg/2019/05/14/the-next-part-of-the-process/

|

|

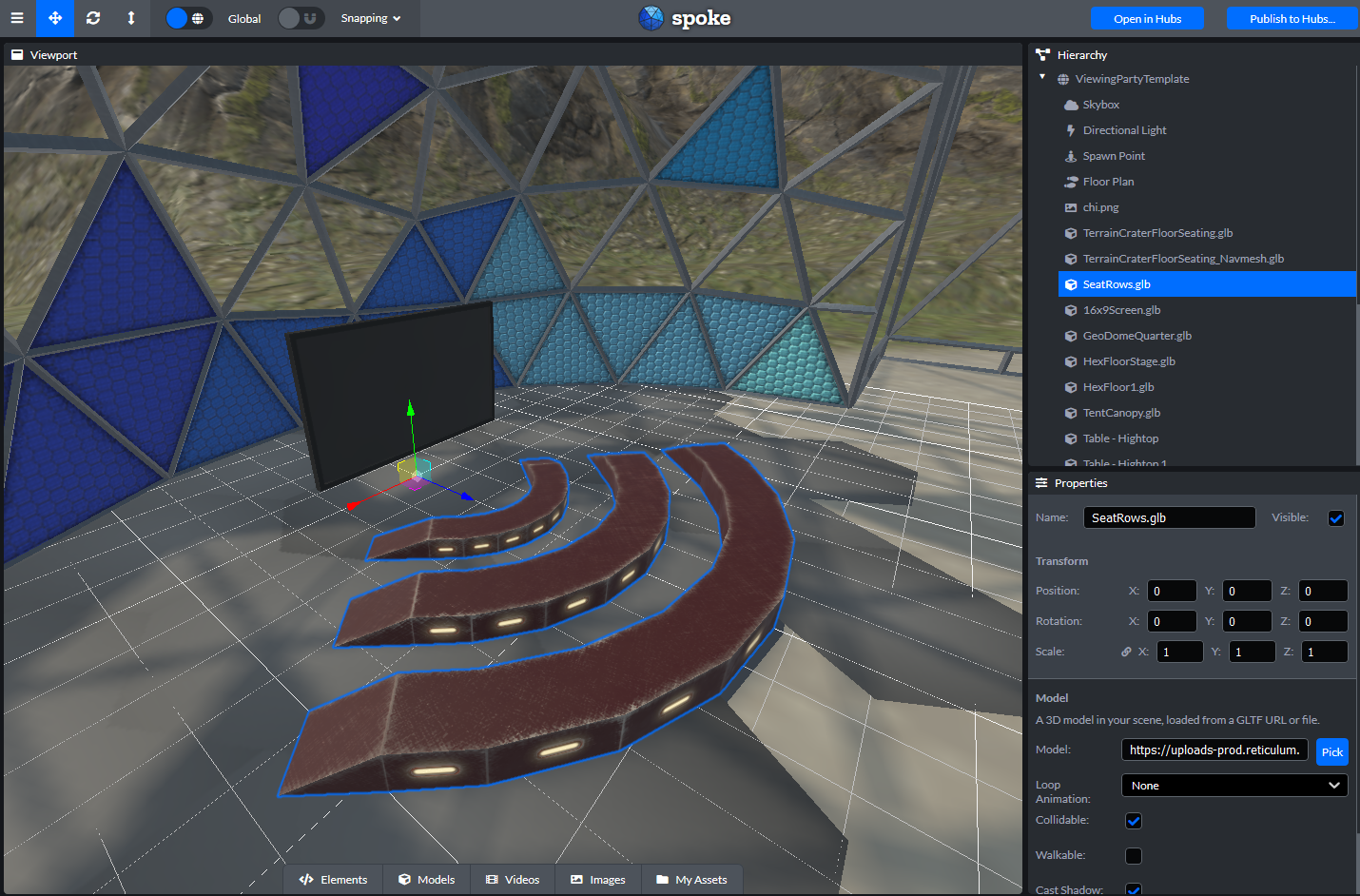

Mozilla VR Blog: Spoke, now on the Web |

Spoke, the editor that lets you create 3D scenes for use in Hubs, is now available as a fully featured web app. When we announced the beta for Spoke back in October, it was the first step towards making the process of creating social VR spaces easier for everyone. At Mozilla, we believe in the power of the web, and it was a natural decision for us to make Spoke more widely available by making the editor entirely available online - no downloads required.

The way that we communicate is often guided by the spaces that we are in. We use our understanding of the environment to give us cues to the tone of the room, and understanding how to build environments that reflect different use cases for social collaboration is an important element of how we view the Hubs platform. With Spoke, we want everyone to have the creative control over their rooms from the ground (plane) up.

We’re constantly impressed by the content that 3D artists and designers create and we think that Spoke is the next step in making it easier for everyone to learn how to make their own 3D environments. Spoke isn’t trying to replace the wide range of 3D modeling or animation software out there, we just want to make it easier to bring all of that awesome work into one place so that more people can build with the media all of these artists have shared so generously with the world.

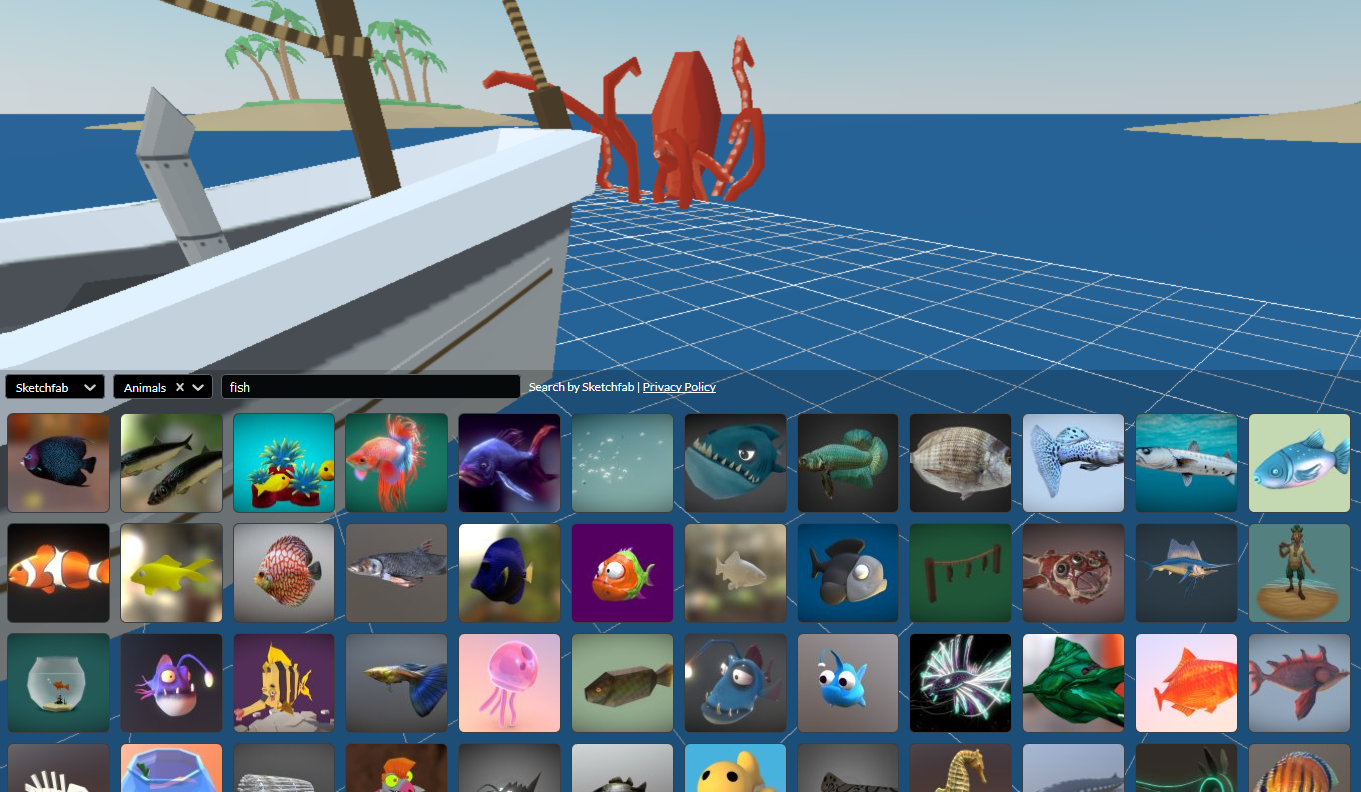

When it comes to building rooms for Hubs, we want everyone to feel empowered to create custom spaces regardless of whether or not they already have experience building 3D environments. Spoke aims to make it as simple as possible to find, add, and remix what’s already out there on the web under the Creative Commons license. You can bring in your own glTF models, find models on Sketchfab and Google Poly, and publish your rooms to Hubs with just a single click, which makes it easier than ever before to create shared spaces. In addition to 3D models, the Spoke editor allows you to bring in images, gifs, and videos for your spaces. Create your own themed rooms in Hubs for movie nights, academic meetups, your favorite Twitch streams: the virtual world is yours to create!

Spoke works by providing an easy-to-use interface to consolidate content into a glTF 2.0 binary (.glb) file that is read by Hubs to generate the base environment for a room. Basing Spoke on glTF, an extensible, standardized 3D file format, makes it possible to export robust scenes that could also be used in other 3D applications or programs.

Once you’ve created scenes in Spoke, you can access them from your Projects page and use them as a base for making new rooms in Hubs. You can keep your scenes private for your own use, or publish them and make them available through the media browser for anyone in Hubs to enjoy. In the future, we plan on adding functionality that allows you to remix environments that others have marked as being open to derivative works.

We want to hear your feedback as you start using Spoke to create environments - try it out at https://hubs.mozilla.com/spoke. You can view the source code and file issues on the GitHub repo, or jump into our community Discord server and say hi in the #spoke channel! If you have specific thoughts or considerations that you want to share with us, feel free to send us an email at hubs@mozilla.com to get in touch. We can’t wait to see what you make!

|

|

The Rust Programming Language Blog: Announcing Rust 1.34.2 |

The Rust team has published a new point release of Rust, 1.34.2. Rust is a programming language that is empowering everyone to build reliable and efficient software.

If you have a previous version of Rust installed via rustup, getting Rust 1.34.2 is as easy as:

$ rustup update stable

If you don't have it already, you can get rustup from the

appropriate page on our website.

What's in 1.34.2 stable

Sean McArthur reported a security vulnerability affecting the standard

library that caused the Error::downcast family of methods

to perform unsound casts when a manual implementation of the

Error::type_id method returned the wrong

TypeId, leading to security issues such as out of bounds

reads/writes/etc.

The Error::type_id method was recently stabilized as part

of Rust 1.34.0. This point release destabilizes it, preventing any code on

the stable and beta channels to implement or use it, awaiting future plans that

will be discussed in issue #60784.

An in-depth explaination of this issue was posted in yesterday's security advisory. The assigned CVE for the vulnerability is CVE-2019-12083.

|

|

Mozilla Reps Community: Rep of the Month – April 2019 |

Please join us in congratulating Lidya Christina, Rep of the Month for April 2019!

Lidya Christina is from Jakarta, Indonesia. Her contribution in SUMO event in 2016 lead her into a proud Mozillian, an active contributor of Mozilla Indonesia and last March 2019 she joined the Reps program.

In addition to that, she’s also a key member that oversees the day to day operational work in Mozilla Community space Jakarta, while at the same time regularly organizing localization event and actively participating in campaigns like Firefox 66 Support Mozilla Sprint, Firefox Fights for you, Become a dark funnel detective and Common Voice sprints.

Congratulations and keep rocking the open web! ![]()

![]()

https://blog.mozilla.org/mozillareps/2019/05/13/rep-of-the-month-april-2019/

|

|

Support.Mozilla.Org: Introducing Josh and Jeremy to the SUMO team |

Today the SUMO team would like to welcome Josh and Jeremy who will be joining our team from Boise, Idaho.

Josh and Jeremy will be joining our team to help out on Support for some of the new efforts Mozilla are working on towards creating a connected and integrated Firefox experience.

They will be helping out with new products, but also providing support on forums and social channels, as well as serving as an escalation point for hard to solve issues.

A bit about Josh:

Hey everyone! My name is Josh Wilson and I will be working as a contractor for Mozilla. I have been working in a variety of customer support and tech support jobs over the past ten years. I enjoy camping and hiking during the summers, and playing console RPG’s in the winters. I recently started cooking Indian food, but this has been quite the learning curve for me. I am so happy to be a part of the Mozilla community and look forward to offering my support.

A bit about Jeremy:

Hello! My name is Jeremy Sanders and I’m a contractor of Mozilla through a small company named PartnerHero. I’ve been working in the field of Information Technology since 2015 and have been working with a variety of government, educational, and private entities. In my free time, I like to get out of the office and go fly fishing, camping, or hiking. I also play quite a few video games such as Counterstrike: Global Offensive and League of Legends. I am very excited to start my time here with Mozilla and begin working in conjunction with the community to provide support for users!

Please say hi to them when you see them!

https://blog.mozilla.org/sumo/2019/05/13/introducing-josh-and-jeremy-to-the-sumo-team/

|

|

The Rust Programming Language Blog: Security advisory for the standard library |

This is a cross-post of the official security advisory. The official post contains a signed version with our PGP key, as well.

The CVE for this vulnerability is CVE-2019-12083.

The Rust team was recently notified of a security vulnerability affecting

manual implementations of Error::type_id and their interaction with the

Error::downcast family of functions in the standard library. If your code

does not manually implement Error::type_id your code is not affected.

Overview

The Error::type_id function in the standard library was stabilized in the

1.34.0 release on 2019-04-11. This function allows acquiring the concrete

TypeId for the underlying error type to downcast back to the original type.

This function has a default implementation in the standard library, but it can

also be overridden by downstream crates. For example, the following is

currently allowed on Rust 1.34.0 and Rust 1.34.1:

struct MyType;

impl Error for MyType {

fn type_id(&self) -> TypeId {

// Enable safe casting to `String` by accident.

TypeId::of::()

}

}

When combined with the Error::downcast* family of methods this can enable

safe casting of a type to the wrong type, causing security issues such as out

of bounds reads/writes/etc.

Prior to the 1.34.0 release this function was not stable and could not be either implemented or called in stable Rust.

Affected Versions

The Error::type_id function was first stabilized in Rust 1.34.0, released on

2019-04-11. The Rust 1.34.1 release, published 2019-04-25, is also affected.

The Error::type_id function has been present, unstable, for all releases of

Rust since 1.0.0 meaning code compiled with nightly may have been affected at

any time.

Mitigations

Immediate mitigation of this bug requires removing manual implementations of

Error::type_id, instead inheriting the default implementation which is

correct from a safety perspective. It is not the intention to have

Error::type_id return TypeId instances for other types.

For long term mitigation we are going to destabilize this function. This is

unfortunately a breaking change for users calling Error::type_id and for

users overriding Error::type_id. For users overriding it's likely memory

unsafe, but users calling Error::type_id have only been able to do so on

stable for a few weeks since the last 1.34.0 release, so it's thought that the

impact will not be too great to overcome.

We will be releasing a 1.34.2 point release on 2019-05-14 (tomorrow) which

reverts #58048 and destabilizes the Error::type_id function. The

upcoming 1.35.0 release along with the beta/nightly channels will also all be

updated with a destabilization.

The final fate of the Error::type_id API isn't decided upon just yet and is

the subject of #60784. No action beyond destabilization is currently

planned so nightly code may continue to exhibit this issue. We hope to fully

resolve this in the standard library soon.

Timeline of events

- Thu, May 9, 2019 at 14:07 PM - Bug reported to security@rust-lang.org

- Thu, May 9, 2019 at 15:10 PM - Alex reponds, confirming the bug

- Fri, May 10, 2019 - Plan for mitigation developed and implemented

- Mon, May 13, 2019 - PRs posted to GitHub for stable/beta/master branches

- Mon, May 13, 2019 - Security list informed of this issue

- (planned) Tue, May 14, 2019 - Rust 1.34.2 is released with a fix for this issue

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Sean McArthur, who found this bug and reported it to us in accordance with our security policy.

https://blog.rust-lang.org/2019/05/13/Security-advisory.html

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: The curl user survey 2019 |

For the 6th consecutive year, the curl project is running a “user survey” to learn more about what people are using curl for, what think think of curl, what the need of curl and what they wish from curl going forward.

As in most projects, we love to learn more about our users and how to improve. For this, we need your input to guide us where to go next and what to work on going forward.

Please consider donating a few minutes of your precious time and tell me about your views on curl. How do you use it and what would you like to see us fix?

The survey will be up for 14 straight days and will be taken down at midnight (CEST) May 26th. We appreciate if you encourage your curl friends to participate in the survey.

Bonus: the analysis from the 2018 survey.

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2019/05/13/the-curl-user-survey-2019/

|

|

Nick Desaulniers: f() vs f(void) in C vs C++ |

TL;DR

Prefer f(void) in C to potentially save a 2B instruction per function call

when targeting x86_64 as a micro-optimization. -Wstrict-prototypes can help.

Doesn’t matter for C++.

The Problem

While messing around with some C code in

godbolt Compiler Explorer,

I kept noticing a particular funny case. It seemed with my small test cases

that sometimes function calls would zero out the return register before calling

a function that took no arguments, but other times not. Upon closer

inspection, it seemed like a difference between function definitions,

particularly f() vs f(void). For example, the following C code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

would generate the following assembly:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

In particular, focus on the call the foo vs the call to bar. foo is

preceded with xorl %eax, %eax (X ^ X == 0, and is the shortest encoding for

an instruction that zeroes a register on the variable length encoded x86_64,

which is why its used a lot such as in setting the return value). (If you’re

curious about the pushq/popq, see

point #1.)

Now I’ve seen zeroing before (see

point #3

and remember that %al is the lowest byte of %eax and %rax), but if it was

done for the call to foo, then why was it not additionally done for the call

to bar? %eax being x86_64’s return register for the C ABI should be treated

as call clobbered. So if you set it, then made a function call that may have

clobbered it (and you can’t deduce otherwise), then wouldn’t you have to reset

it to make an additional function call?

Let’s look at a few more cases and see if we can find the pattern. Let’s take

a look at 2 sequential calls to foo vs 2 sequential calls to bar:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

So it should be pretty clear now that the pattern is f(void) does not

generate the xorl %eax, %eax, while f() does. What gives, aren’t they

declaring f the same; a function that takes no parameters? Unfortunately, in

C the answer is no, and C and C++ differ here.

An explanation

f() is not necessarily “f takes no arguments” but more of “I’m not telling

you what arguments f takes (but it’s not variadic).” Consider this perfectly

legal C and C++ code:

1 2 | |

It seems that C++ inherited this from C, but only in C++ does f() seems to

have the semantics of “f takes no arguments,” as the previous examples all no

longer have the xorl %eax, %eax. Same for f(void) in C or C++. That’s

because foo() and foo(int) are two different function in C++ thanks to

function overloading (thanks reddit user /u/OldWolf2). Also, it seems that C

supported this difference for backwards compatibility w/ K & R C.

1 2 | |

Is an error in C, but in C++ thanks to function overloading these are two

separate functions! (_Z3barv vs _Z3bari). (Thanks HN user

pdpi, for helping me

understand this. Cunningham’s Law ftw.)

Needless to say, If you write code like that where your function declarations and definitions do not match, you will be put in prison. Do not pass go, do not collect $200). Control flow integrity analysis is particularly sensitive to these cases, manifesting in runtime crashes.

What could a sufficiently smart compiler do to help?

-Wall and -Wextra will just flag the -Wunused-parameter. We need the

help of -Wmissing-prototypes to flag the mismatch between declaration and

definition. (An aside; I had a hard time remembering which was the declaration

and which was the definition when learning C++. The mnemonic I came up with

and still use today is: think of definition as in muscle definition; where the

meat of the function is. Declarations are just hot air.) It’s not until we

get to -Wstrict-prototypes do we get a warning that we should use f(void).

-Wstrict-prototypes is kind of a stylistic warning, so that’s why it’s not

part of -Wall or -Wextra. Stylistic warnings are in bikeshed territory

(*cough* -Wparentheses *cough*).

One issue with C and C++’s style of code sharing and encapsulation via headers

is that declarations often aren’t enough for the powerful analysis techniques

of production optimizing compilers (whether or not a pointer

“escapes”

is a big one that comes to mind). Let’s see if a “sufficiently smart compiler”

could notice when we’ve declared f(), but via observation of the definition

of f() noticed that we really only needed the semantics of f(void).

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

A ha! So by having the full definition of foo2 in this case in the same

translation unit, Clang was able to deduce that foo2 didn’t actually need the

semantics of f(), so it could skip the xorl %eax, %eax we’d seen for f()

style definitions earlier. If we change foo2 to a declaration (such as would

be the case if it was defined in an external translation unit, and its

declaration included via header), then Clang can no longer observe whether

foo2 definition differs or not from the declaration.

So Clang can potentially save you a single instruction (xorl %eax, %eax)

whose encoding is only 2B, per function call to functions declared in the style

f(), but only IF the definition is in the same translation unit and doesn’t

differ from the declaration, and you happen to be targeting x86_64. *deflated

whew* But usually it can’t because it’s only been provided the declaration via

header.

Conclusion

I certainly think f() is prettier than f(void) (so C++ got this right),

but pretty code may not always be the fastest and it’s not always

straightforward when to prefer one over the other.

So it seems that f() is ok for strictly C++ code. For C or mixed C and C++,

f(void) might be better.

References

- https://stackoverflow.com/q/6212665/1027966

- https://stackoverflow.com/q/693788/1027966

- https://stackoverflow.com/q/12643202/1027966

- https://stackoverflow.com/q/51032/1027966

- https://stackoverflow.com/q/416345/1027966

- https://stackoverflow.com/q/41803937/1027966

- http://david.tribble.com/text/cdiffs.htm#C99-empty-parm

- https://godbolt.org/z/nsgGpt

- https://godbolt.org/z/IORbBb

- https://godbolt.org/z/51s7K0

- https://bugs.llvm.org/show_bug.cgi?id=41851 (the maintainer of Clang cites the relevant part of the C11 spec for this)

http://nickdesaulniers.github.io/blog/2019/05/12/f-vs-f-void-in-c-vs-c-plus-plus/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: tiny-curl |

curl, or libcurl specifically, is probably the world’s most popular and widely used HTTP client side library counting more than six billion installs.

curl is a rock solid and feature-packed library that supports a huge amount of protocols and capabilities that surpass most competitors. But this comes at a cost: it is not the smallest library you can find.

Within a 100K

Instead of being happy with getting told that curl is “too big” for certain use cases, I set a goal for myself: make it possible to build a version of curl that can do HTTPS and fit in 100K (including the wolfSSL TLS library) on a typical 32 bit architecture.

As a comparison, the tiny-curl shared library when built on an x86-64 Linux, is smaller than 25% of the size as the default Debian shipped library is.

FreeRTOS

But let’s not stop there. Users with this kind of strict size requirements are rarely running a full Linux installation or similar OS. If you are sensitive about storage to the exact kilobyte level, you usually run a more slimmed down OS as well – so I decided that my initial tiny-curl effort should be done on FreeRTOS. That’s a fairly popular and free RTOS for the more resource constrained devices.

This port is still rough and I expect us to release follow-up releases soon that improves the FreeRTOS port and ideally also adds support for other popular RTOSes. Which RTOS would you like to support for that isn’t already supported?

Offer the libcurl API for HTTPS on FreeRTOS, within 100 kilobytes.

Maintain API

I strongly believe that the power of having libcurl in your embedded devices is partly powered by the libcurl API. The API that you can use for libcurl on any platform, that’s been around for a very long time and for which you can find numerous examples for on the Internet and in libcurl’s extensive documentation. Maintaining support for the API was of the highest priority.

Patch it

My secondary goal was to patch as clean as possible so that we can upstream patches into the main curl source tree for the changes makes sense and that aren’t disturbing to the general code base, and for the work that we can’t we should be able to rebase on top of the curl code base with as little obstruction as possible going forward.

Keep the HTTPS basics

I just want to do HTTPS GET

That’s the mantra here. My patch disables a lot of protocols and features:

- No protocols except HTTP(S) are supported

- HTTP/1 only

- No cookie support

- No date parsing

- No alt-svc

- No HTTP authentication

- No DNS-over-HTTPS

- No .netrc parsing

- No HTTP multi-part formposts

- No shuffled DNS support

- No built-in progress meter

Although they’re all disabled individually so it is still easy to enable one or more of these for specific builds.

Downloads and versions?

Tiny-curl 0.9 is the first shot at this and can be downloaded from wolfSSL. It is based on curl 7.64.1.

Most of the patches in tiny-curl are being upstreamed into curl in the #3844 pull request. I intend to upstream most, if not all, of the tiny-curl work over time.

License

The FreeRTOS port of tiny-curl is licensed GPLv3 and not MIT like the rest of curl. This is an experiment to see how we can do curl work like this in a sustainable way. If you want this under another license, we’re open for business over at wolfSSL!

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Google’s Ad API is Better Than Facebook’s, But… |

|

|

Support.Mozilla.Org: SUMO/Firefox Accounts integration |

One of Mozilla’s goals is to deepen relationships with our users and better connect them with our products. For support this means integrating Firefox Accounts (FxA) as the authentication layer on support.mozilla.org

What does this mean?

Currently support.mozilla.org is using its own auth/login system where users are logging in using their username and password. We will replace this auth system with Firefox Accounts and both users and contributors will be asked to connect their existing profiles to FxA.

This will not just help align support.mozilla.org with other Mozilla products but also be a vehicle for users to discover FxA and its many benefits.

In order to achieve this we are looking at the following milestones (the dates are tentative):

Transition period (May-June)

We will start with a transition period where users can log in using both their old username/password as well as Firefox Accounts. During this period new users registering to the site will only be able to create an account through Firefox Accounts. Existing users will get a recommendation to connect their Firefox Account through their existing profile but they will still be able to use their old username/password auth method if they wish. Our intention is to have banners across the site that will let users know about the change and how to switch to Firefox Accounts. We will also send email communications to active users (logged in at least once in the last 3 years).

Switching to Firefox Accounts will also bring a small change to our AAQ (Ask a Question) flow. Currently when users go through the Ask a Question flow they are prompted to login/create an account in the middle of the flow (which is a bit of a frustrating experience). As we’re switching to Firefox Accounts and that login experience will no longer work, we will be moving the login/sign up step at the beginning of the flow – meaning users will have to log in first before they can go through the AAQ. During the transition period non-authenticated users will not be able to use the AAQ flow. This will get back to normal during the Soft Launch period.

Soft Launch (end of June)

After the transition period we will enter a so-called “Soft Launch” period where we integrate the full new log in/sign up experiences and do the fine tuning. By this time the AAQ flow should have been updated and non-authenticated users can use it again. We will also send more emails to active users who haven’t done the switch yet and continue having banners on the site to inform people of the change.

Full Launch (July-August)

If the testing periods above go well, we should be ready to do the full switch in July or August. This means that no old SUMO logins will be accepted and all users will be asked to switch over to Firefox Accounts. We will also do a final round of communications.

Please note: As we’re only changing the authentication mechanism we don’t expect there to be any changes to your existing profile, username and contribution history. If you do encounter an issue please reach out to Madalina or Tasos (or file a bug through Bugzilla).

We’re excited about this change, but are also aware that we might encounter a few bumps on the way. Thank you for your support in making this happen.

If you want to help out, as always you can follow our progress on Github and/or join our weekly calls.

SUMO staff team

https://blog.mozilla.org/sumo/2019/05/10/sumo-firefox-accounts-integration/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: What we do when things go wrong |

We strive to make Firefox a great experience. Last weekend we failed, and we’re sorry.

An error on our part prevented new add-ons from being installed, and stopped existing add-ons from working. Now that we’ve been able to restore this functionality for the majority of Firefox users, we want to explain a bit about what happened and tell you what comes next.

Add-ons are an important feature of Firefox. They enable you to customize your browser and add valuable functionality to your online experience. We know how important this is, which is why we’ve spent a great deal of time over the past few years coming up with ways to make add-ons safer and more secure. However, because add-ons are so powerful, we’ve also worked hard to build and deploy systems to protect you from malicious add-ons. The problem here was an implementation error in one such system, with the failure mode being that add-ons were disabled. Although we believe that the basic design of our add-ons system is sound, we will be working to refine these systems so similar problems do not occur in the future.

In order to address this issue as quickly as possible, we used our “Studies” system to deploy the initial fix, which requires users to be opted in to Telemetry. Some users who had opted out of Telemetry opted back in, in order to get the initial fix as soon as possible. As we announced in the Firefox Add-ons blog at 2019-05-08T23:28:00Z there is now no longer a need to have Studies on to receive updates anymore; please check that your settings match your personal preferences before we re-enable Studies, which will happen sometime after 2019-05-13T16:00:00Z. In order to respect our users’ potential intentions as much as possible, based on our current set up, we will be deleting all of our source Telemetry and Studies data for our entire user population collected between 2019-05-04T11:00:00Z and 2019-05-11T11:00:00Z.

Our CTO, Eric Rescorla, shares more about what happened technically in this post.

We would like to extend our thanks to the people who worked hard to address this issue, including the hundred or so community members and employees localizing content and answering questions on https://support.mozilla.org/, Twitter, and Reddit.

There’s a lot more detail we will be sharing as part of a longer post-mortem which we will make public — including details on how we went about fixing this problem and why we chose this approach. You deserve a full accounting, but we didn’t want to wait until that process was complete to tell you what we knew so far. We let you down and what happened might have shaken your confidence in us a bit, but we hope that you’ll give us a chance to earn it back.

The post What we do when things go wrong appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2019/05/09/what-we-do-when-things-go-wrong/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Technical Details on the Recent Firefox Add-on Outage |

Editor’s Note: May 9, 8:22 pt – Updated as follows: (1) Fixed verb tense (2) Clarified the situation with downstream distros. For more detail, see Bug 1549886.

Recently, Firefox had an incident in which most add-ons stopped working. This was due to an error on our end: we let one of the certificates used to sign add-ons expire which had the effect of disabling the vast majority of add-ons. Now that we’ve fixed the problem for most users and most people’s add-ons are restored, I wanted to walk through the details of what happened, why, and how we repaired it.

Background: Add-Ons and Add-On Signing

Although many people use Firefox out of the box, Firefox also supports a powerful extension mechanism called “add-ons”. Add-ons allow users to add third party features to Firefox that extend the capabilities we offer by default. Currently there are over 15,000 Firefox add-ons with capabilities ranging from blocking ads to managing hundreds of tabs.

Firefox requires that all add-ons that are installed be digitally signed. This requirement is intended to protect users from malicious add-ons by requiring some minimal standard of review by Mozilla staff. Before we introduced this requirement in 2015, we had serious problems with malicious add-ons.

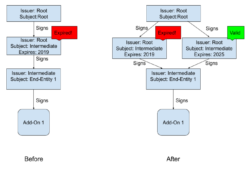

The way that the add-on signing works is that Firefox is configured with a preinstalled “root certificate”. That root is stored offline in a hardware security module (HSM). Every few years it is used to sign a new “intermediate certificate” which is kept online and used as part of the signing process. When an add-on is presented for signature, we generate a new temporary “end-entity certificate” and sign that using the intermediate certificate. The end-entity certificate is then used to sign the add-on itself. Shown visually, this looks like this:

Note that each certificate has a “subject” (to whom the certificate belongs) and an “issuer” (the signer). In the case of the root, these are the same entity, but for other certificates, the issuer of a certificate is the subject of the certificate that signed it.

An important point here is that each add-on is signed by its own end-entity certificate, but nearly all add-ons share the same intermediate certificate [1]. It is this certificate that encountered a problem: Each certificate has a fixed period during which it is valid. Before or after this window, the certificate won’t be accepted, and an add-on signed with that certificate can’t be loaded into Firefox. Unfortunately, the intermediate certificate we were using expired just after 1AM UTC on May 4, and immediately every add-on that was signed with that certificate become unverifiable and could not be loaded into Firefox.

Although add-ons all expired around midnight, the impact of the outage wasn’t felt immediately. The reason for this is that Firefox doesn’t continuously check add-ons for validity. Rather, all add-ons are checked about every 24 hours, with the time of the check being different for each user. The result is that some people experienced problems right away, some people didn’t experience them until much later. We at Mozilla first became aware of the problem around 6PM Pacific time on Friday May 3 and immediately assembled a team to try to solve the issue.

Damage Limitation

Once we realized what we were up against, we took several steps to try to avoid things getting any worse.

First, we disabled signing of new add-ons. This was sensible at the time because we were signing with a certificate that we knew was expired. In retrospect, it might have been OK to leave it up, but it also turned out to interfere with the “hardwiring a date” mitigation we discuss below (though eventually didn’t use) and so it’s good we preserved the option. Signing is now back up.

Second, we immediately pushed a hotfix which suppressed re-validating the signatures on add-ons. The idea here was to avoid breaking users who hadn’t re-validated yet. We did this before we had any other fix, and have removed it now that fixes are available.

Working in Parallel

In theory, fixing a problem like this looks simple: make a new, valid certificate and republish every add-on with that certificate. Unfortunately, we quickly determined that this wouldn’t work for a number of reasons:

- There are a very large number of add-ons (over 15,000) and the signing service isn’t optimized for bulk signing, so just re-signing every add-on would take longer than we wanted.

- Once add-ons were signed, users would need to get a new add-on. Some add-ons are hosted on Mozilla’s servers and Firefox would update those add-ons within 24 hours, but users would have to manually update any add-ons that they had installed from other sources, which would be very inconvenient.

Instead, we focused on trying to develop a fix which we could provide to all our users with little or no manual intervention.

After examining a number of approaches, we quickly converged on two major strategies which we pursued in parallel:

- Patching Firefox to change the date which is used to validate the certificate. This would make existing add-ons magically work again, but required shipping a new build of Firefox (a “dot release”).

- Generate a replacement certificate that was still valid and somehow convince Firefox to accept it instead of the existing, expired certificate.

We weren’t sure that either of these would work, so we decided to pursue them in parallel and deploy the first one that looked like it was going to work. At the end of the day, we ended up deploying the second fix, the new certificate, which I’ll describe in some more detail below.

A Replacement Certificate

As suggested above, there are two main steps we had to follow here:

- Generate a new, valid, certificate.

- Install it remotely in Firefox.

In order to understand why this works, you need to know a little more about how Firefox validates add-ons. The add-on itself comes as a bundle of files that includes the certificate chain used to sign it. The result is that the add-on is independently verifiable as long as you know the root certificate, which is configured into Firefox at build time. However, as I said, the intermediate certificate was broken, so the add-on wasn’t actually verifiable.

However, it turns out that when Firefox tries to validate the add-on, it’s not limited to just using the certificates in the add-on itself. Instead, it tries to build a valid chain of certificates starting at the end-entity certificate and continuing until it gets to the root. The algorithm is complicated, but at a high level, you start with the end-entity certificate and then find a certificate whose subject is equal to the issuer of the end-entity certificate (i.e., the intermediate certificate). In the simple case, that’s just the intermediate that shipped with the add-on, but it could be any certificate that the browser happens to know about. If we can remotely add a new, valid, certificate, then Firefox will try that as well. The figure below shows the situation before and after we install the new certificate.

Once the new certificate is installed, Firefox has two choices for how to validate the certificate chain, use the old invalid certificate (which won’t work) and use the new valid certificate (which will work). An important feature here is that the new certificate has the same subject name and public key as the old certificate, so that its signature on the End-Entity certificate is valid. Fortunately, Firefox is smart enough to try both until it finds a path that works, so the add-on becomes valid again. Note that this is the same logic we use for validating TLS certificates, so it’s relatively well understood code that we were able to leverage.[2]

The great thing about this fix is that it doesn’t require us to change any existing add-on. As long as we get the new certificate into Firefox, then even add-ons which are carrying the old certificate will just automatically verify. The tricky bit then becomes getting the new certificate into Firefox, which we need to do automatically and remotely, and then getting Firefox to recheck all the add-ons that may have been disabled.

Normandy and the Studies System

Ironically, the solution to this problem is a special type of add-on called a system add-on (SAO). In order to let us do research studies, we have developed a system called Normandy which lets us serve SAOs to Firefox users. Those SAOs automatically execute on the user’s browser and while they are usually used for running experiments, they also have extensive access to Firefox internal APIs. Important for this case, they can add new certificates to the certificate database that Firefox uses to verify add-ons.[3]

So the fix here is to build a SAO which does two things:

- Install the new certificate we have made.

- Force the browser to re-verify every add-on so that the ones which were disabled become active.

But wait, you say. Add-ons don’t work so how do we get it to run? Well, we sign it with the new certificate!

Putting it all together… and what took so long?

OK, so now we’ve got a plan: issue a new certificate to replace the old one, build a system add-on to install it on Firefox, and deploy it via Normandy. Starting from about 6 PM Pacific on Friday May 3, we were shipping the fix in Normandy at 2:44 AM, or after less than 9 hours, and then it took another 6-12 hours before most of our users had it. This is actually quite good from a standing start, but I’ve seen a number of questions on Twitter about why we couldn’t get it done faster. There are a number of steps that were time consuming.

First, it took a while to issue the new intermediate certificate. As I mentioned above, the Root certificate is in a hardware security module which is stored offline. This is good security practice, as you use the Root very rarely and so you want it to be secure, but it’s obviously somewhat inconvenient if you want to issue a new certificate on an emergency basis. At any rate, one of our engineers had to drive to the secure location where the HSM is stored. Then there were a few false starts where we didn’t issue exactly the right certificate, and each attempt cost an hour or two of testing before we knew exactly what to do.

Second, developing the system add-on takes some time. It’s conceptually very simple, but even simple programs require taking some care, and we really wanted to make sure we didn’t make things worse. And before we shipped the SAO, we had to test it, and that takes time, especially because it has to be signed. But the signing system was disabled, so we had to find some workarounds for that.

Finally, once we had the SAO ready to ship, it still takes time to deploy. Firefox clients check for Normandy updates every 6 hours, and of course many clients are offline, so it takes some time for the fix to propagate through the Firefox population. However, at this point we expect that most people have received the update and/or the dot release we did later.

Final Steps

While the SAO that was deployed with Studies should fix most users, it didn’t get to everyone. In particular, there are a number of types of affected users who will need another approach:

- Users who have disabled either Telemetry or Studies.

- Users on Firefox for Android (Fennec), where we don’t have Studies.

- Users of downstream builds of Firefox ESR that don’t opt-in to

telemetry reporting. - Users who are behind HTTPS Man-in-the-middle proxies, because our add-on installation systems enforce key pinning for these connections, which proxies interfere with.

- Users of very old builds of Firefox which the Studies system can’t reach.

We can’t really do anything about the last group — they should update to a new version of Firefox anyway because older versions typically have quite serious unfixed security vulnerabilities. We know that some people have stayed on older versions of Firefox because they want to run old-style add-ons, but many of these now work with newer versions of Firefox. For the other groups we have developed a patch to Firefox that will install the new certificate once people update. This was released as a “dot release” so people will get it — and probably have already — through the ordinary update channel. If you have a downstream build, you’ll need to wait for your build maintainer to update.

We recognize that none of this is perfect. In particular, in some cases, users lost data associated with their add-ons (an example here is the “multi-account containers” add-on).

We were unable to develop a fix that would avoid this side effect, but we believe this is the best approach for the most users in the short term. Long term, we will be looking at better architectural approaches for dealing with this kind of issue.

Lessons

First, I want to say that the team here did amazing work: they built and shipped a fix in less than 12 hours from the initial report. As someone who sat in the meeting where it happened, I can say that people were working incredibly hard in a tough situation and that very little time was wasted.

With that said, obviously this isn’t an ideal situation and it shouldn’t have happened in the first place. We clearly need to adjust our processes both to make this and similar incidents it less likely to happen and to make them easier to fix.

We’ll be running a formal post-mortem next week and will publish the list of changes we intend to make, but in the meantime here are my initial thoughts about what we need to do. First, we should have a much better way of tracking the status of everything in Firefox that is a potential time bomb and making sure that we don’t find ourselves in a situation where one goes off unexpectedly. We’re still working out the details here, but at minimum we need to inventory everything of this nature.

Second, we need a mechanism to be able to quickly push updates to our users even when — especially when — everything else is down. It was great that we are able to use the Studies system, but it was also an imperfect tool that we pressed into service, and that had some undesirable side effects. In particular, we know that many users have auto-updates enabled but would prefer not to participate in Studies and that’s a reasonable preference (true story: I had it off as well!) but at the same time we need to be able to push updates to our users; whatever the internal technical mechanisms, users should be able to opt-in to updates (including hot-fixes) but opt out of everything else. Additionally, the update channel should be more responsive than what we have today. Even on Monday, we still had some users who hadn’t picked up either the hotfix or the dot release, which clearly isn’t ideal. There’s been some work on this problem already, but this incident shows just how important it is.

Finally, we’ll be looking more generally at our add-on security architecture to make sure that it’s enforcing the right security properties at the least risk of breakage.

We’ll be following up next week with the results of a more thorough post-mortem, but in the meantime, I’ll be happy to answer questions by email at ekr-blog@mozilla.com.

[1] A few very old add-ons were signed with a different intermediate.

[2] Readers who are familiar with the WebPKI will recognize that this is also the way that cross-certification works.

[3] Technical note: we aren’t adding the certificate with any special privileges; it gets its authority by being signed for the root. We’re just adding it to the pool of certificates which can be used by Firefox. So, it’s not like we are adding a new privileged certificate to Firefox.

The post Technical Details on the Recent Firefox Add-on Outage appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/05/technical-details-on-the-recent-firefox-add-on-outage/

|

|

Chris H-C: Google I/O Extended 2019 – Report |

I attended a Google I/O Extended event on Tuesday at Google’s Kitchener office. It’s a get-together where there are demos, talks, workshops, and networking opportunities centred around watching the keynote live on the screen.

I treat it as an opportunity to keep an eye on what they’re up to this time, and a reminder that I know absolutely no one in the tech scene around here.

The first part of the day was a workshop about how to build Actions for the Google Assistant. I found the exercise to be very interesting.

The writing of the Action itself wasn’t interesting, that was a bunch of whatever. But it was interesting that it refused to work unless you connected it to a Google Account that had Web & Search Activity tracking turned on. Also I found it interesting that, though they said it required Chrome, it worked just fine on Firefox. It was interesting listening to laptops (including mine) across the room belt out welcome phrases because the simulator defaults to a hot mic and a loud speaker. It was interesting to notice that the presenter spent thirty seconds talking about how to name your project, and zero seconds talking about the Terms of Use of the application we were being invited to use. It was interesting to see that the settings defaulted to allowing you to test on all devices registered to the Google Account, without asking.

After the workshop the tech head of the Google Home App stood up and delivered a talk about trying to get manufacturers to agree on how to talk to Google Home and the Google Assistant.

I asked whether these efforts in trying to normalize APIs and protocols was leading them to publish a standard with a standards body. “No idea, sorry.”

Then I noticed the questions from the crowd were following a theme: “Can we get finer privacy controls?” (The answer seemed to be that Google believes the controls are already fine enough) “How do you educate users about the duration the data is retained?” (It’s in the Terms of Service, but it isn’t read aloud. But Google logs every “consent moment” and keeps track of settings) “For the GDPR was there a challenge operating in multiple countries?” (Yes. They admitted that some of the “fine enough” privacy controls are finer in certain jurisdictions due to regs.) And, after the keynote, someone in the crowd asked what features Android might adopt (self-destruct buttons, maybe) to protect against Border Security-style threats.

It was very heartening to hear a room full of tech nerds from Toronto and Waterloo Region ask questions about Privacy and Security of a tech giant. It was incredibly validating to hear from the keynote that Chrome is considering privacy protections Firefox introduced last year.

Maybe we at Mozilla aren’t crazy to think that privacy is important, that users care about it, that it is at risk and big tech companies have the power and the responsibility to protect it.

Maybe. Maybe not.

Just keep those questions coming.

:chutten

https://chuttenblog.wordpress.com/2019/05/09/google-i-o-extended-2019-report/

|

|

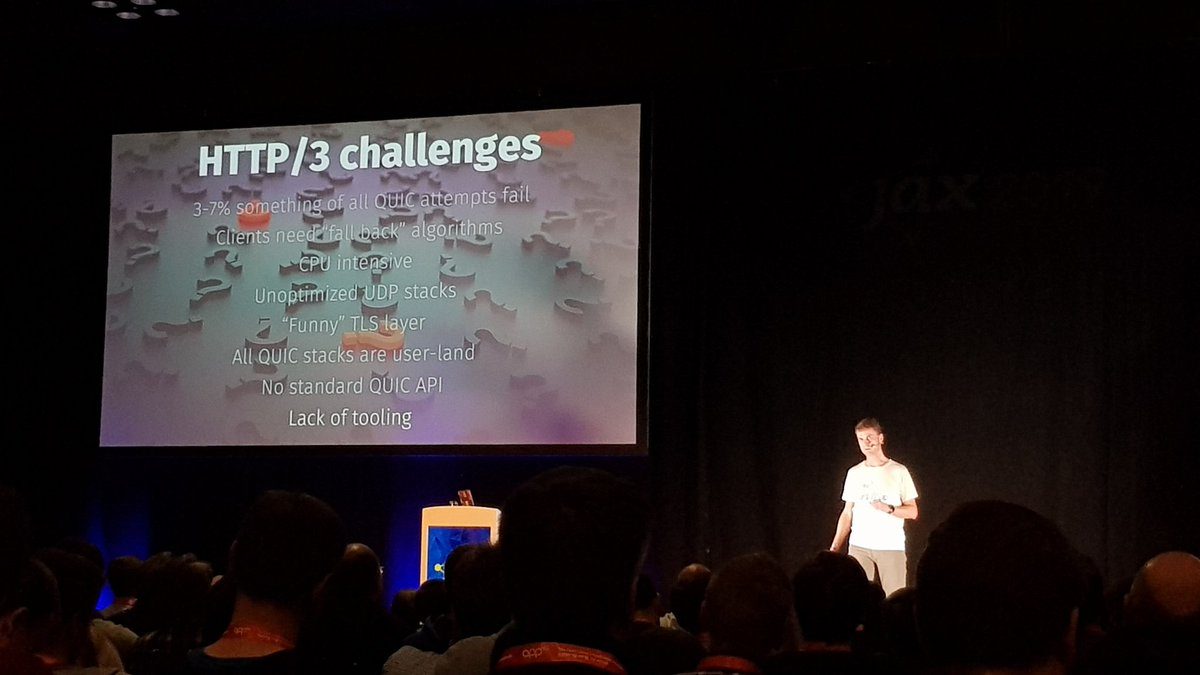

Daniel Stenberg: Sometimes I speak |

I view myself as primarily a software developer. Perhaps secondary as someone who’s somewhat knowledgeable in networking and is participating in protocol development and discussions. I do not regularly proclaim myself to be a “speaker” or someone who’s even very good at talking in front of people.

Time to wake up and face reality? I’m slowly starting to realize that I’m actually doing more presentations than ever before in my life and I’m enjoying it.

Since October 2015 I’ve done 53 talks and presentations in front of audiences – in ten countries. That’s one presentation done every 25 days on average. (The start date of this count is a little random but it just happens that I started to keep a proper log then.) I’ve talked to huge audiences and to small. I done presentations that were appreciated and I’ve done some that were less successful.

My increased frequency in speaking engagements coincides with me starting to work full-time from home back in 2014. Going to places to speak is one way to get out of the house and see the “real world” a little bit and see what the real people are doing. And a chance to hang out with humans for a change. Besides, I only ever talk on topics that are dear to me and that I know intimately well so I rarely feel pressure when delivering them. 2014 – 2015 was also the time frame when HTTP/2 was being finalized and the general curiosity on that new protocol version helped me find opportunities back then.

Public speaking is like most other things: surprisingly enough, practice actually makes you better at it! I still have a lot to learn and improve, but speaking many times has for example made me better at figuring out roughly how long time I need to deliver a particular talk. It has taught me to “find myself” better when presenting and be more relaxed and the real me – no need to put up a facade of some kind or pretend. People like seeing that there’s a real person there.

I’m not even getting that terribly nervous before my talks anymore. I used to really get a raised pulse for the first 45 talks or so, but by doing it over and over and over I think the practice has made me more secure and more relaxed in my attitude to the audience and the topics. I think it has made me a slightly better presenter and it certainly makes me enjoy it more.

I’m not “a good presenter”. I can deliver a talk and I can do it with dignity and I think the audience is satisfied with me in most cases, but by watching actual good presenters talk I realize that I still have a long journey ahead of me. Of course, parts of the explanation is that, to connect with the beginning of this post, I’m a developer. I don’t talk for a living and I actually very rarely practice my presentations very much because I don’t feel I can spend that time.

Some of the things that are still difficult include:

The money issue. I actually am a developer and that’s what I do for a living. Taking time off the development to prepare a presentation, travel to a distant place, sacrifice my spare time for one or more days and communicating something interesting to an audience that demands and expects it to be both good and reasonably entertaining takes time away from that development. Getting travel and accommodation compensated is awesome but unfortunately not enough. I need to insist on getting paid for this. I frequently turn down speaking opportunities when they can’t pay me for my time.

Saying no. Oh my god do I have a hard time to do this. This year, I’ve been invited to so many different conferences and the invitations keep flying in. For every single received invitation, I get this warm and comfy feeling and I feel honored and humbled by the fact that someone actually wants me to come to their conference or gathering to talk. There’s the calendar problem: I can’t be in two places at once. Then I also can’t plan events too close to each other in time to avoid them holding up “real work” too much or to become too much of a nuisance to my family. Sometimes there’s also the financial dilemma: if I can’t get compensation, it gets tricky for me to do it, no matter how good the conference seems to be and the noble cause they’re working for.

Feedback. To determine what parts of the presentation that should be improved for the next time I speak of the same or similar topic, which parts should be removed and if something should be expanded, figuring what works and what doesn’t work is vital. For most talks I’ve done, there’s been no formal way to provide or receive this feedback, and for the small percentage that had a formal feedback form or a scoring system or similar, taking care of a bunch of distributed grades (for example “your talk was graded 4.2 on a scale between 1 and 5”) and random comments – either positive or negative – is really hard… I get the best feedback from close friends who dare to tell me the truth as it is.

Conforming to silly formats. Slightly different, but some places want me to send me my slides in, either a long time before the event (I’ve had people ask me to provide way over a week(!) before), or they dictate that the slides should be sent to them using Microsoft Powerpoint, PDF or some other silly format. I want to use my own preferred tools when designing presentations as I need to be able to reuse the material for more and future presentations. Sure, I can convert to other formats but that usually ruins formatting and design. Then a lot the time and sweat I put into making a fine and good-looking presentation is more or less discarded! Fortunately, most places let me plug in my laptop and everything is fine!

Upcoming talks?

As a little service to potential audience members and conference organizers, I’m listing all my upcoming speaking engagements on a dedicated page on my web site:

https://daniel.haxx.se/talks.html

I try to keep that page updated to reflect current reality. It also shows that some organizers are forward-planning waaaay in advance…

Invite someone like me to talk?

Here’s some advice on how to invite a speaker (like me) with style:

- Ask well in advance (more than 2-3 months preferably, probably not more than 9). When I agree to a talk, others who ask for talks in close proximity to that date will get declined. I get a surprisingly large amount of invitations for events just a month into the future or so, and it rarely works for me to get those into my calendar in that time frame.

- Do not assume for-free delivery. I think it is good tone of you to address the price/charge situation, if not in the first contact email at least in the following discussion. If you cannot pay, that’s also useful information to provide early.

- If the time or duration of the talk you’d like is “unusual” (ie not 30-60 minutes) do spell that out early on.

- Surprisingly often I get invited to talk without a specified topic or title. The inviter then expects me to present that. Since you contact me you clearly had some kind of vision of what a talk by me would entail, it would make my life easier if that vision was conveyed as it could certainly help me produce a talk subject that will work!

What I bring

To every presentation I do, I bring my laptop. It has HDMI and USB-C ports. I also carry a HDMI-to-VGA adapter for the few installations that still use the old “projector port”. Places that need something else than those ports tend to have their own converters already since they’re then used with equipment not being fitted for their requirements.

I always bring my own clicker (the “remote” with which I can advance to next slide). I never use the laser-pointer feature, but I like being able to move around on the stage and not have to stand close to the keyboard when I present.

Presentations

I never create my presentations with video or sound in them, and I don’t do presentations that need Internet access. All this to simplify and to reduce the risk of problems.

I work hard on limiting the amount of text on each slide, but I also acknowledge that if a slide set should have value after-the-fact there needs to be a certain amount. I’m a fan of revealing the text or graphics step-by-step on the slides to avoid having half the audience reading ahead on the slide and not listening.

I’ve settled on 16:9 ratio for all presentations. Luckily, the remaining 4:3 projectors are now scarce.

I always make and bring a backup of my presentations in PDF format so that basically “any” computer could display that in case of emergency. Like if my laptop dies. As mentioned above, PDF is not an ideal format, but as a backup it works.

|

|

Mike Hommey: Announcing git-cinnabar 0.5.1 |

Git-cinnabar is a git remote helper to interact with mercurial repositories. It allows to clone, pull and push from/to mercurial remote repositories, using git.

These release notes are also available on the git-cinnabar wiki.

What’s new since 0.5.0?

- Updated git to 2.21.0 for the helper.

- Experimental native mercurial support (used when mercurial libraries are not available) now has feature parity.

- Try to read the git system config from the same place as git does. This fixes native HTTPS support with Git on Windows.

- Avoid pushing more commits than necessary in some corner cases (see e.g. https://bugzilla.mozilla.org/show_bug.cgi?id=1529360).

- Added an –abbrev argument for

git cinnabar {git2hg,hg2git}to display shortened sha1s. - Can now pass multiple revisions to

git cinnabar fetch. - Don’t require the requests python module for

git cinnabar download. - Fixed

git cinnabar fsckfile checks to actually report errors. - Properly return an error code from

git cinnabar rollback. - Track last fsck’ed metadata and allow

git cinnabar rollback --fsckto go back to last known good metadata directly. git cinnabar reclonecan now be rolled back.- Added support for git bundles as cinnabarclone source.

- Added alternate styles of remote refs.

- More resilient to interruptions when HTTP Range requests are supported.

- Fixed off-by-one when storing mercurial heads.

- Better handling of mercurial branchmap tips.

- Better support for end of parts in bundle v2.

- Improvements handling urls to local mercurial repositories.

- Fixed compatibility with (very) old mercurial servers when using mercurial 5.0 libraries.

- Converted Continuous Integration scripts to Python 3.

|

|

Mozilla Thunderbird: WeTransfer File Transfer Now Available in Thunderbird |

WeTransfer’s file-sharing service is now available within Thunderbird for sending large files (up to 2GB) for free, without signing up for an account.

Even better, sharing large files can be done without leaving the composer. While writing an email, just attach a large file and you will be prompted to choose whether you want to use file link, which will allow you to share a large file with a link to download it. Via this prompt you can select to use WeTransfer.

You can also enable File Link through the Preferences menu, under the attachments tab and the Outgoing page. Click “Add…” and choose “WeTransfer” from the drop down menu.

Once WeTransfer is set up in Thunderbird it will be the default method of linking for files over the size that you have specified (you can see that is set to 5MB in the screenshot above).

WeTransfer and Thunderbird are both excited to be able to work together on this great feature for our users. The Thunderbird team thinks that this will really improve the experience of collaboration and and sharing for our users.

WeTransfer is also proud of this feature. Travis Brown, WeTransfer VP of Business Development says about the collaboration:

“Mozilla and WeTransfer share similar values. We’re focused on the user and on maintaining our user’s privacy and an open internet. We’ll continue to work with their team across multiple areas and put privacy at the front of those initiatives.”

We hope that all our users will give this feature a try and enjoy being able to share the files they want with co-workers, friends, and family – easily.

https://blog.mozilla.org/thunderbird/2019/05/wetransfer-file-transfer-now-available-in-thunderbird/

|

|