Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Pyodide: Bringing the scientific Python stack to the browser |

Pyodide is an experimental project from Mozilla to create a full Python data science stack that runs entirely in the browser.

The impetus for Pyodide came from working on another Mozilla project, Iodide, which we presented in an earlier post. Iodide is a tool for data science experimentation and communication based on state-of-the-art web technologies. Notably, it’s designed to perform data science computation within the browser rather than on a remote kernel.

Unfortunately, the “language we all have” in the browser, JavaScript, doesn’t have a mature suite of data science libraries, and it’s missing a number of features that are useful for numerical computing, such as operator overloading. We still think it’s worthwhile to work on changing that and moving the JavaScript data science ecosystem forward. In the meantime, we’re also taking a shortcut: we’re meeting data scientists where they are by bringing the popular and mature Python scientific stack to the browser.

It’s also been argued more generally that Python not running in the browser represents an existential threat to the language—with so much user interaction happening on the web or on mobile devices, it needs to work there or be left behind. Therefore, while Pyodide tries to meet the needs of Iodide first, it is engineered to be useful on its own as well.

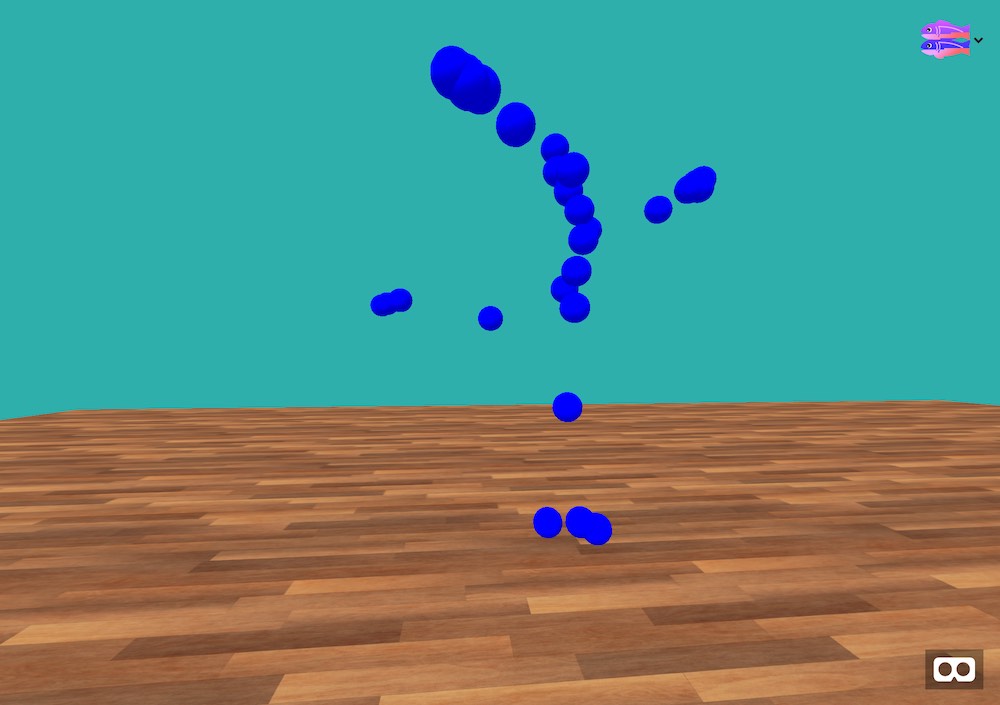

Pyodide gives you a full, standard Python interpreter that runs entirely in the browser, with full access to the browser’s Web APIs. In the example above (50 MB download), the density of calls to the City of Oakland, California’s “311” local information service is plotted in 3D. The data loading and processing is performed in Python, and then it hands off to Javascript and WebGL for the plotting.

For another quick example, here’s a simple doodling script that lets you draw in the browser window:

from js import document, iodide

canvas = iodide.output.element('canvas')

canvas.setAttribute('width', 450)

canvas.setAttribute('height', 300)

context = canvas.getContext("2d")

context.strokeStyle = "#df4b26"

context.lineJoin = "round"

context.lineWidth = 5

pen = False

lastPoint = (0, 0)

def onmousemove(e):

global lastPoint

if pen:

newPoint = (e.offsetX, e.offsetY)

context.beginPath()

context.moveTo(lastPoint[0], lastPoint[1])

context.lineTo(newPoint[0], newPoint[1])

context.closePath()

context.stroke()

lastPoint = newPoint

def onmousedown(e):

global pen, lastPoint

pen = True

lastPoint = (e.offsetX, e.offsetY)

def onmouseup(e):

global pen

pen = False

canvas.addEventListener('mousemove', onmousemove)

canvas.addEventListener('mousedown', onmousedown)

canvas.addEventListener('mouseup', onmouseup)

And this is what it looks like:

The best way to learn more about what Pyodide can do is to just go and try it! There is a demo notebook (50MB download) that walks through the high-level features. The rest of this post will be more of a technical deep-dive into how it works.

Prior art

There were already a number of impressive projects bringing Python to the browser when we started Pyodide. Unfortunately, none addressed our specific goal of supporting a full-featured mainstream data science stack, including NumPy, Pandas, Scipy, and Matplotlib.

Projects such as Transcrypt transpile (convert) Python to JavaScript. Because the transpilation step itself happens in Python, you either need to do all of the transpiling ahead of time, or communicate with a server to do that work. This doesn’t really meet our goal of letting the user write Python in the browser and run it without any outside help.

Projects like Brython and Skulpt are rewrites of the standard Python interpreter to JavaScript, therefore, they can run strings of Python code directly in the browser. Unfortunately, since they are entirely new implementations of Python, and in JavaScript to boot, they aren’t compatible with Python extensions written in C, such as NumPy and Pandas. Therefore, there’s no data science tooling.

PyPyJs is a build of the alternative just-in-time compiling Python implementation, PyPy, to the browser, using emscripten. It has the potential to run Python code really quickly, for the same reasons that PyPy does. Unfortunately, it has the same issues with performance with C extensions that PyPy does.

All of these approaches would have required us to rewrite the scientific computing tools to achieve adequate performance. As someone who used to work a lot on Matplotlib, I know how many untold person-hours that would take: other projects have tried and stalled, and it’s certainly a lot more work than our scrappy upstart team could handle. We therefore needed to build a tool that was based as closely as possible on the standard implementations of Python and the scientific stack that most data scientists already use.

After a discussion with some of Mozilla’s WebAssembly wizards, we saw that the key to building this was emscripten and WebAssembly: technologies to port existing code written in C to the browser. That led to the discovery of an existing but dormant build of Python for emscripten, cpython-emscripten, which was ultimately used as the basis for Pyodide.

emscripten and WebAssembly

There are many ways of describing what emscripten is, but most importantly for our purposes, it provides two things:

- A compiler from C/C++ to WebAssembly

- A compatibility layer that makes the browser feel like a native computing environment

WebAssembly is a new language that runs in modern web-browsers, as a complement to JavaScript. It’s a low-level assembly-like language that runs with near-native performance intended as a compilation target for low-level languages like C and C++. Notably, the most popular interpreter for Python, called CPython, is implemented in C, so this is the kind of thing emscripten was created for.

Pyodide is put together by:

- Downloading the source code of the mainstream Python interpreter (CPython), and the scientific computing packages (NumPy, etc.)

- Applying a very small set of changes to make them work in the new environment

- Compiling them to WebAssembly using emscripten’s compiler

If you were to just take this WebAssembly and load it in the browser, things would look very different to the Python interpreter than they do when running directly on top of your operating system. For example, web browsers don’t have a file system (a place to load and save files). Fortunately, emscripten provides a virtual file system, written in JavaScript, that the Python interpreter can use. By default, these virtual “files” reside in volatile memory in the browser tab, and they disappear when you navigate away from the page. (emscripten also provides a way for the file system to store things in the browser’s persistent local storage, but Pyodide doesn’t use it.)

By emulating the file system and other features of a standard computing environment, emscripten makes moving existing projects to the web browser possible with surprisingly few changes. (Some day, we may move to using WASI as the system emulation layer, but for now emscripten is the more mature and complete option).

Putting it all together, to load Pyodide in your browser, you need to download:

- The compiled Python interpreter as WebAssembly.

- A bunch of JavaScript provided by emscripten that provides the system emulation.

- A packaged file system containing all the files the Python interpreter will need, most notably the Python standard library.

These files can be quite large: Python itself is 21MB, NumPy is 7MB, and so on. Fortunately, these packages only have to be downloaded once, after which they are stored in the browser’s cache.

Using all of these pieces in tandem, the Python interpreter can access the files in its standard library, start up, and then start running the user’s code.

What works and doesn’t work

We run CPython’s unit tests as part of Pyodide’s continuous testing to get a handle on what features of Python do and don’t work. Some things, like threading, don’t work now, but with the newly-available WebAssembly threads, we should be able to add support in the near future.

Other features, like low-level networking sockets, are unlikely to ever work because of the browser’s security sandbox. Sorry to break it to you, your hopes of running a Python minecraft server inside your web browser are probably still a long way off. Nevertheless, you can still fetch things over the network using the browser’s APIs (more details below).

How fast is it?

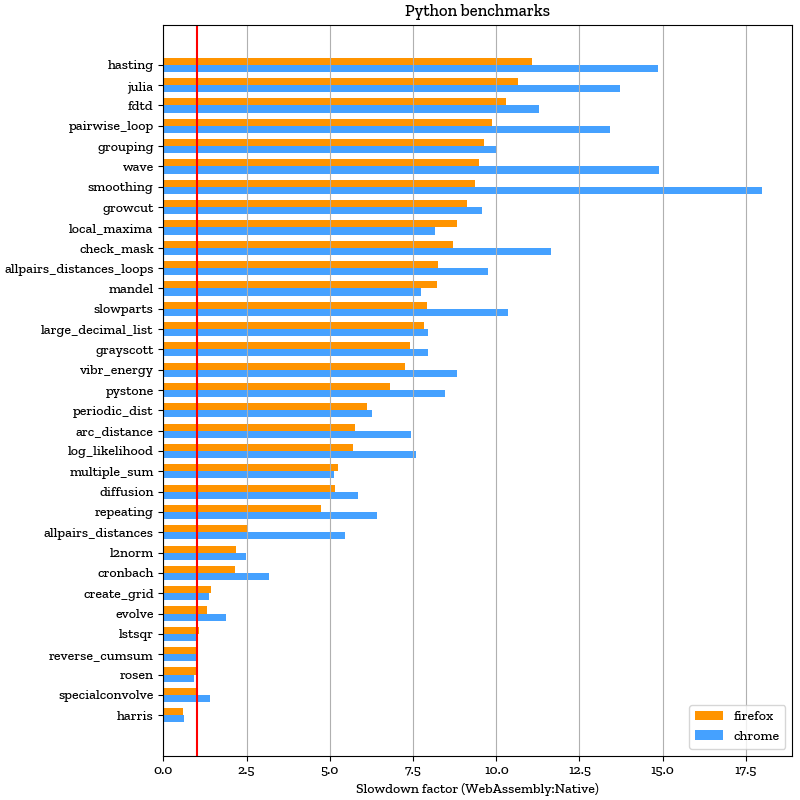

Running the Python interpreter inside a JavaScript virtual machine adds a performance penalty, but that penalty turns out to be surprisingly small — in our benchmarks, around 1x-12x slower than native on Firefox and 1x-16x slower on Chrome. Experience shows that this is very usable for interactive exploration.

Notably, code that runs a lot of inner loops in Python tends to be slower by a larger factor than code that relies on NumPy to perform its inner loops. Below are the results of running various Pure Python and Numpy benchmarks in Firefox and Chrome compared to natively on the same hardware.

Interaction between Python and JavaScript

If all Pyodide could do is run Python code and write to standard out, it would amount to a cool trick, but it wouldn’t be a practical tool for real work. The real power comes from its ability to interact with browser APIs and other JavaScript libraries at a very fine level. WebAssembly has been designed to easily interact with the JavaScript running in the browser. Since we’ve compiled the Python interpreter to WebAssembly, it too has deep integration with the JavaScript side.

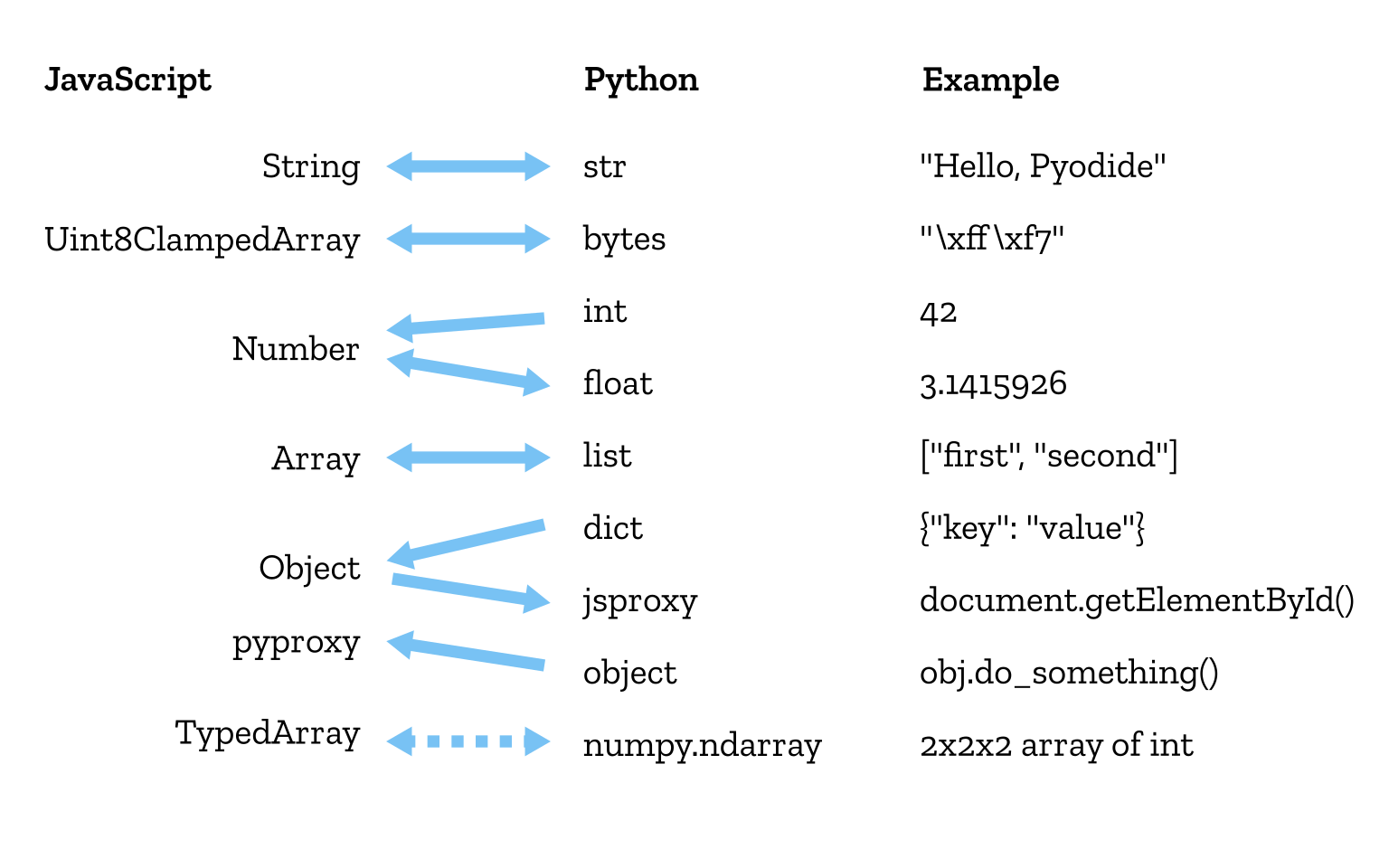

Pyodide implicitly converts many of the built-in data types between Python and JavaScript. Some of these conversions are straightforward and obvious, but as always, it’s the corner cases that are interesting.

Python treats dicts and object instances as two distinct types. dicts (dictionaries) are just mappings of keys to values. On the other hand, objects generally have methods that “do something” to those objects. In JavaScript, these two concepts are conflated into a single type called Object. (Yes, I’ve oversimplified here to make a point.)

Without really understanding the developer’s intention for the JavaScript Object, it’s impossible to efficiently guess whether it should be converted to a Python dict or object. Therefore, we have to use a proxy and let “duck typing” resolve the situation.

Proxies are wrappers around a variable in the other language. Rather than simply reading the variable in JavaScript and rewriting it in terms of Python constructs, as is done for the basic types, the proxy holds on to the original JavaScript variable and calls methods on it “on demand”. This means that any JavaScript variable, no matter how custom, is fully accessible from Python. Proxies work in the other direction, too.

Duck typing is the principle that rather than asking a variable “are you a duck?” you ask it “do you walk like a duck?” and “do you quack like a duck?” and infer from that that it’s probably a duck, or at least does duck-like things. This allows Pyodide to defer the decision on how to convert the JavaScript Object: it wraps it in a proxy and lets the Python code using it decide how to handle it. Of course, this doesn’t always work, the duck may actually be a rabbit. Thus, Pyodide also provides ways to explicitly handle these conversions.

It’s this tight level of integration that allows a user to do their data processing in Python, and then send it to JavaScript for visualization. For example, in our Hipster Band Finder demo, we show loading and analyzing a data set in Python’s Pandas, and then sending it to JavaScript’s Plotly for visualization.

Accessing Web APIs and the DOM

Proxies also turn out to be the key to accessing the Web APIs, or the set of functions the browser provides that make it do things. For example, a large part of the Web API is on the document object. You can get that from Python by doing:

from js import documentThis imports the document object in JavaScript over to the Python side as a proxy. You can start calling methods on it from Python:

document.getElementById("myElement")All of this happens through proxies that look up what the document object can do on-the-fly. Pyodide doesn’t need to include a comprehensive list of all of the Web APIs the browser has.

Of course, using the Web API directly doesn’t always feel like the most Pythonic or user-friendly way to do things. It would be great to see the creation of a user-friendly Python wrapper for the Web API, much like how jQuery and other libraries have made the Web API easier to use from JavaScript. Let us know if you’re interested in working on such a thing!

Multidimensional Arrays

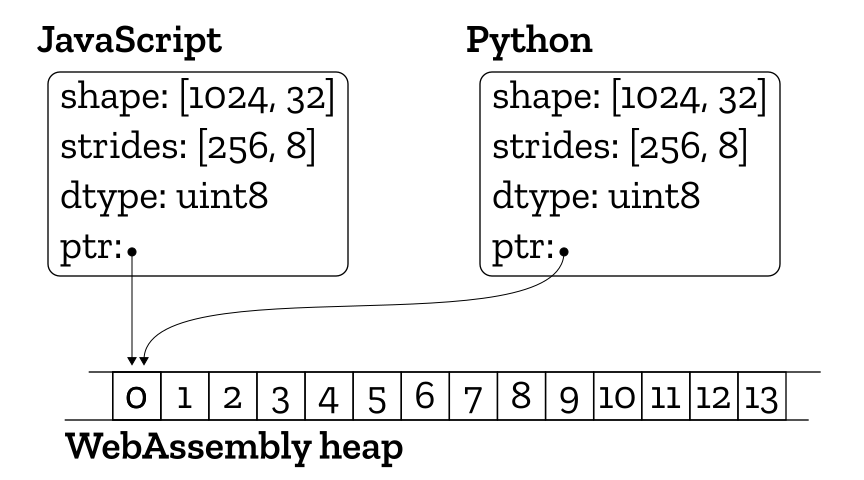

There are important data types that are specific to data science, and Pyodide has special support for these as well. Multidimensional arrays are collections of (usually numeric) values, all of the same type. They tend to be quite large, and knowing that every element is the same type has real performance advantages over Python’s lists or JavaScript’s Arrays that can hold elements of any type.

In Python, NumPy arrays are the most common implementation of multidimensional arrays. JavaScript has TypedArrays, which contain only a single numeric type, but they are single dimensional, so the multidimensional indexing needs to be built on top.

Since in practice these arrays can get quite large, we don’t want to copy them between language runtimes. Not only would that take a long time, but having two copies in memory simultaneously would tax the limited memory the browser has available.

Fortunately, we can share this data without copying. Multidimensional arrays are usually implemented with a small amount of metadata that describes the type of the values, the shape of the array and the memory layout. The data itself is referenced from that metadata by a pointer to another place in memory. It’s an advantage that this memory lives in a special area called the “WebAssembly heap,” which is accessible from both JavaScript and Python. We can simply copy the metadata (which is quite small) back and forth between the languages, keeping the pointer to the data referring to the WebAssembly heap.

This idea is currently implemented for single-dimensional arrays, with a suboptimal workaround for higher-dimensional arrays. We need improvements to the JavaScript side to have a useful object to work with there. To date there is no one obvious choice for JavaScript multidimensional arrays. Promising projects such as Apache Arrow and xnd’s ndarray are working exactly in this problem space, and aim to make the passing of in-memory structured data between language runtimes easier. Investigations are ongoing to build off of these projects to make this sort of data conversion more powerful.

Real-time interactive visualization

One of the advantages of doing the data science computation in the browser rather than in a remote kernel, as Jupyter does, is that interactive visualizations don’t have to communicate over a network to reprocess and redisplay their data. This greatly reduces the latency — the round trip time it takes from the time the user moves their mouse to the time an updated plot is displayed to the screen.

Making that work requires all of the technical pieces described above to function together in tandem. Let’s look at this interactive example that shows how log-normal distributions work using matplotlib. First, the random data is generated in Python using Numpy. Next, Matplotlib takes that data, and draws it using its built-in software renderer. It sends the pixels back to the JavaScript side using Pyodide’s support for zero-copy array sharing, where they are finally rendered into an HTML canvas. The browser then handles getting those pixels to the screen. Mouse and keyboard events used to support interactivity are handled by callbacks that call from the web browser back into Python.

Packaging

The Python scientific stack is not a monolith—it’s actually a collection of loosely-affiliated packages that work together to create a productive environment. Among the most popular are NumPy (for numerical arrays and basic computation), Scipy (for more sophisticated general-purpose computation, such as linear algebra), Matplotlib (for visualization) and Pandas (for tabular data or “data frames”). You can see the full and constantly updated list of the packages that Pyodide builds for the browser here.

Some of these packages were quite straightforward to bring into Pyodide. Generally, anything written in pure Python without any extensions in compiled languages is pretty easy. In the moderately difficult category are projects like Matplotlib, which required special code to display plots in an HTML canvas. On the extremely difficult end of the spectrum, Scipy has been and remains a considerable challenge.

Roman Yurchak worked on making the large amount of legacy Fortran in Scipy compile to WebAssembly. Kirill Smelkov improved emscripten so shared objects can be reused by other shared objects, bringing Scipy to a more manageable size. (The work of these outside contributors was supported by Nexedi). If you’re struggling porting a package to Pyodide, please reach out to us on Github: there’s a good chance we may have run into your problem before.

Since we can’t predict which of these packages the user will ultimately need to do their work, they are downloaded to the browser individually, on demand. For example, when you import NumPy:

import numpy as npPyodide fetches the NumPy library (and all of its dependencies) and loads them into the browser at that time. Again, these files only need to be downloaded once, and are stored in the browser’s cache from then on.

Adding new packages to Pyodide is currently a semi-manual process that involves adding files to the Pyodide build. We’d prefer, long term, to take a distributed approach to this so anyone could contribute packages to the ecosystem without going through a single project. The best-in-class example of this is conda-forge. It would be great to extend their tools to support WebAssembly as a platform target, rather than redoing a large amount of effort.

Additionally, Pyodide will soon have support to load packages directly from PyPI (the main community package repository for Python), if that package is pure Python and distributes its package in the wheel format. This gives Pyodide access to around 59,000 packages, as of today.

Beyond Python

The relative early success of Pyodide has already inspired developers from other language communities, including Julia, R, OCaml, Lua, to make their language runtimes work well in the browser and integrate with web-first tools like Iodide. We’ve defined a set of levels to encourage implementors to create tighter integrations with the JavaScript runtime:

- Level 1: Just string output, so it’s useful as a basic console REPL (read-eval-print-loop).

- Level 2: Converts basic data types (numbers, strings, arrays and objects) to and from JavaScript.

- Level 3: Sharing of class instances (objects with methods) between the guest language and JavaScript. This allows for Web API access.

- Level 4: Sharing of data science related types (n-dimensional arrays and data frames) between the guest language and JavaScript.

We definitely want to encourage this brave new world, and are excited about the possibilities of having even more languages interoperating together. Let us know what you’re working on!

Conclusion

If you haven’t already tried Pyodide in action, go try it now! (50MB download)

It’s been really gratifying to see all of the cool things that have been created with Pyodide in the short time since its public launch. However, there’s still lots to do to turn this experimental proof-of-concept into a professional tool for everyday data science work. If you’re interested in helping us build that future, come find us on gitter, github and our mailing list.

Huge thanks to Brendan Colloran, Hamilton Ulmer and William Lachance, for their great work on Iodide and for reviewing this article, and Thomas Caswell for additional review.

The post Pyodide: Bringing the scientific Python stack to the browser appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/04/pyodide-bringing-the-scientific-python-stack-to-the-browser/

|

|

Mozilla VR Blog: Announcing the Hubs Discord Bot |

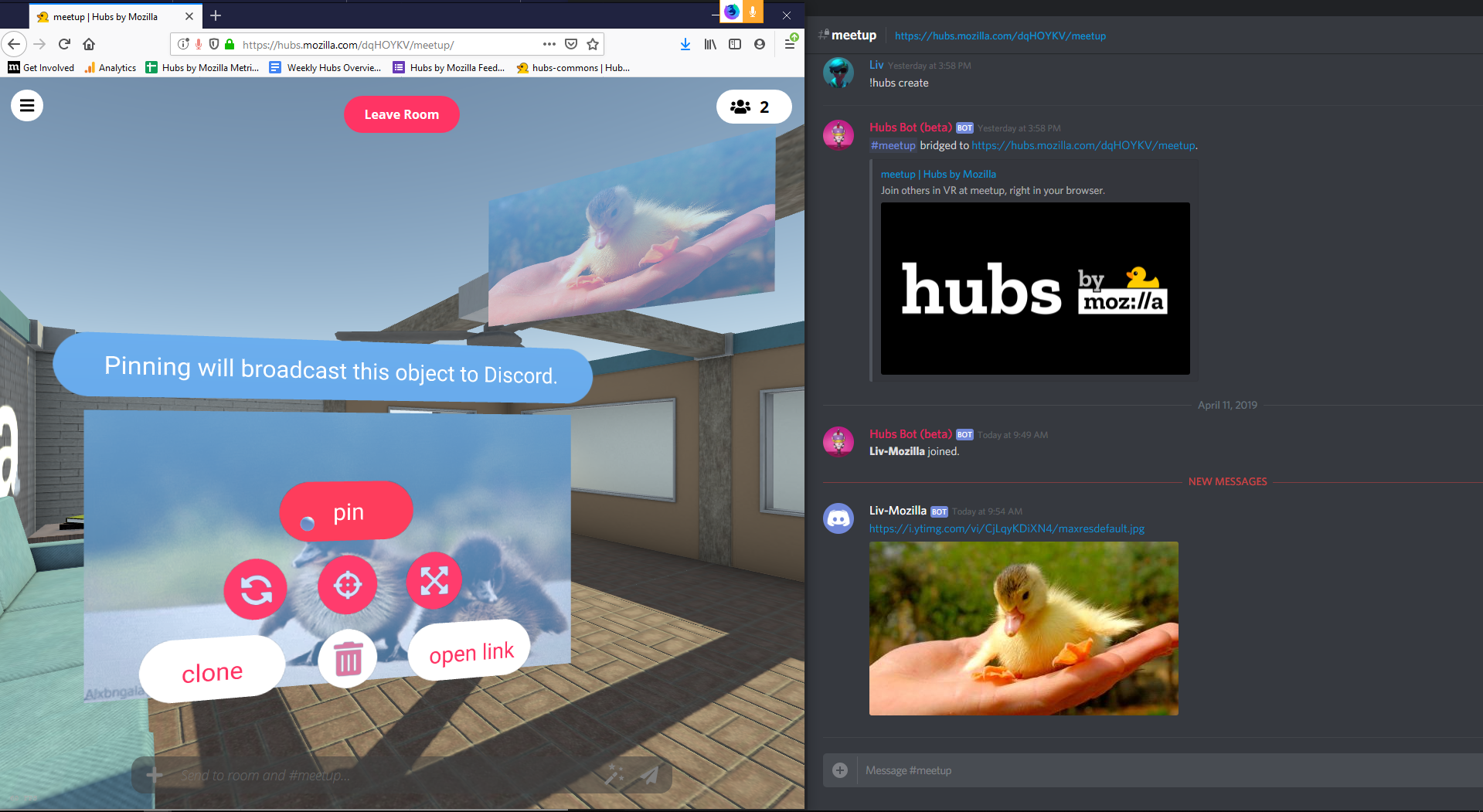

We’re excited to announce an official Hubs integration with Discord, a platform that provides text and voice chat for communities. In today's digital world, the ways we stay connected with our friends, family, and co-workers is evolving. Our established social networks span across different platforms, and we believe that shared virtual reality should build on those relationships and that they enhance the way we communicate with the people we care about. Being co-present as avatars in a shared 3D space is a natural progression for the tools we use today, and we’re building on that idea with Hubs to allow you to create private spaces where your conversations, content, and data is protected.

In recent years, Discord has grown in popularity for communities organized around games and technology, and is the platform we use internally on the Hubs development team for product development discussions. Using Discord as a persistent platform that is open to the public gives us the ability to be open about our ongoing work and initiatives on the Hubs team and integrate the community’s feedback into our product planning and development. If you’re a member of the Discord server for Hubs, you may have already seen the bot in action during our internal testing this month!

The Hubs Discord integration allows members to use their Discord identity to connect to rooms and connects a Discord channel with a specific Hubs room in order to capture the text chat, photos taken, and media shared between users in each space. With the ability to add web content to rooms in Hubs, users who are co-present together are able to collaborate and entertain one another, watch videos, chat, share their screen / webcam feed, and pull in 3D objects from Sketchfab and Google Poly. Users will be able to chat in the linked Discord channel to send messages, see the media added to the connected Hubs room, and easily get updates on who has joined or left at any given time.

We believe that embodied avatar presence will empower communities to be more creative, communicative, and collaborative - and that all of that should be doable without replacing or excluding your existing networks. Your rooms belong to you and the people you choose to share them with, and we feel strongly that everyone should be able to meet in secure spaces where their privacy is protected.

In the coming months, we plan to introduce additional platform integrations and new tools related to room management, authentication, and identity. While you will be able to continue to use Hubs without a persistent identity or login, having an account for the Hubs platform or using your existing identity on a platform such as Discord grants you additional permissions and abilities for the rooms you create. We plan to work closely with communities who are interested in joining the closed beta to help us understand how embodied communication works for them in order to focus our product planning on what meets their needs.

You can see the Hubs Discord integration in action live on the public Hubs Community Discord server for our weekly meetings. If you run a Discord server and are interested in participating in the closed beta for the Hubs Discord bot, you can learn more on the Hubs website.

|

|

Mozilla Security Blog: Mozilla’s Common CA Database (CCADB) promotes Transparency and Collaboration |

The Common CA Database (CCADB) is helping us protect individuals’ security and privacy on the internet and deliver on our commitment to use transparent community-based processes to promote participation, accountability and trust. It is a repository of information about Certificate Authorities (CAs) and their root and subordinate certificates that are used in the web PKI, the publicly-trusted system which underpins secure connections on the web. The Common CA Database (CCADB) paves the way for more efficient and cost-effective management of root stores and helps make the internet safer for everyone. For example, the CCADB automatically detects and alerts root store operators when a root CA has outdated audit statements or a gap between audit periods. This is important, because audit statements provide assurance that a CA is following required procedures so that they do not issue fraudulent certificates.

Through the CCADB we are extending the checks and balances on root CAs to subordinate CAs to provide similar assurance that the subordinate CAs are not issuing fraudulent certificates. Root CAs, who are directly included in Mozilla’s program, can have subordinate CAs who also issue SSL/TLS certificates that are trusted by Firefox. There are currently about 150 root certificates in Mozilla’s root store, which leads to over 3,100 subordinate CA certificates that are trusted by Firefox. In our efforts to ensure that all subordinate CAs follow the rules, we require that they be disclosed in the CCADB along with their audit statements.

Additionally, the CCADB is making it possible for Mozilla to implement Intermediate CA Preloading in Firefox, with the goal of improving performance and privacy. Intermediate CA Preloading is a new way to hande websites that are not properly configured to serve up the intermediate certificate along with its SSL/TLS certificate. When other browsers encounter such websites they use a mechanism to connect to the CA and download the certificate just-in-time. Preloading the intermediate certificate data (aka subordinate CA data) from the CCADB avoids the just-in-time network fetch, which delays the connection. Avoiding the network fetch improves privacy, because it prevents disclosing user browsing patterns to the CA that issued the certificate for the misconfigured website.

Mozilla created and runs the CCADB, which is also used and contributed to by Microsoft, Google, Cisco, and Apple. Even though the common CA data is shared, each root store operator has a customized experience in the CCADB, allowing each root store operator to see the data sets that are important for managing root certificates included in their program.

The CCADB:

- Makes root stores more transparent through public-facing reports, encouraging community involvement to help ensure that CAs and subordinate CAs are correctly issuing certificates.

- For example the crt.sh website combines information from the CCADB and Certificate Transparency (CT) logs to identify problematic certificates.

- Adds automation to improve the level and accuracy of management and rule enforcement. For example the CCADB automates:

- Notification to CAs when audit statements are due at both the root and subordinate CA level

- Audit Letter Validation (ALV) via a tool provided by Microsoft

- Sending of communications to CAs and publishing their responses

- Enables CAs to provide their annual updates in one centralized system, rather than communicating those updates to each root store separately; and in the future will enable CAs to apply to multiple root stores with a single application process.

Maintaining a root store containing only credible CAs is vital to the security of our products and the web in general. The major root store operators are using the CCADB to promote efficiency in maintaining root stores, to improve internet security by raising the quality and transparency of CA and subordinate CA data, and to make the internet safer by enforcing regular and contiguous audits that provide assurances that root and subordinate CAs do not issue fraudulent certificates. As such, the CCADB is enabling us to help ensure individuals’ security and privacy on the internet and deliver on our commitment to use transparent community-based processes to promote participation, accountability and trust.

The post Mozilla’s Common CA Database (CCADB) promotes Transparency and Collaboration appeared first on Mozilla Security Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/security/2019/04/15/common-ca-database-ccadb/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: The Bug in Apple’s Latest Marketing Campaign |

Apple’s latest marketing campaign — “Privacy. That’s iPhone” — made us raise our eyebrows.

It’s true that Apple has an impressive track record of protecting users’ privacy, from end-to-end encryption on iMessage to anti-tracking in Safari.

But a key feature in iPhones has us worried, and makes their latest slogan ring a bit hollow.

Each iPhone that Apple sells comes with a unique ID (called an “identifier for advertisers” or IDFA), which lets advertisers track the actions users take when they use apps. It’s like a salesperson following you from store to store while you shop and recording each thing you look at. Not very private at all.

The good news: You can turn this feature off. The bad news: Most people don’t know that feature even exists, let alone that they should turn it off. And we think that they shouldn’t have to.

That’s why we’re asking Apple to change the unique IDs for each iPhone every month. You would still get relevant ads — but it would be harder for companies to build a profile about you over time.

If you agree with us, will you add your name to Mozilla’s petition?

If Apple makes this change, it won’t just improve the privacy of iPhones — it will send Silicon Valley the message that users want companies to safeguard their privacy by default.

At Mozilla, we’re always fighting for technology that puts users’ privacy first: We publish our annual *Privacy Not Included shopping guide. We urge major retailers not to stock insecure connected devices. And our Mozilla Fellows highlight the consequences of technology that makes publicity, and not privacy, the default.

The post The Bug in Apple’s Latest Marketing Campaign appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2019/04/15/the-bug-in-apples-latest-marketing-campaign/

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: How you can take control against online tracking |

Picture this. You arrive at a website you’ve never been to before and the site is full of ads for things you’ve already looked at online. It’s not a difficult … Read more

The post How you can take control against online tracking appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/take-control-against-online-tracking/

|

|

Niko Matsakis: More than coders |

Lately, the compiler team has been changing up the way that we work. Our goal is to make it easier for people to track what we are doing and – hopefully – get involved. This is an ongoing effort, but one thing that has become clear immediately is this: the compiler team needs more than coders.

Traditionally, when we’ve thought about how to “get involved” in the compiler team, we’ve thought about it in terms of writing PRs. But more and more I’m thinking about all the other jobs that go into maintaining the compiler. “What kinds of jobs are these?”, you’re asking. I think there are quite a few, but let me give a few examples:

- Running a meeting – pinging folks, walking through the agenda.

- Design documents and other documentation – describing how the code works, even if you didn’t write it yourself.

- Publicity – talking about what’s going on, tweeting about exciting progress, or helping to circulate calls for help. Think steveklabnik, but for rustc.

- …and more! These are just the tip of the iceberg, in my opinion.

I think we need to surface these jobs more prominently and try to actively recruit people to help us with them. Hence, this blog post.

“We need an open source whenever”

In my keynote at Rust LATAM, I quoted quite liberally from an excellent blog post by Jessica Lord, “Privilege, Community, and Open Source”. There’s one passage that keeps coming back to me:

We also need an open source whenever. Not enough people can or should be able to spare all of their time for open source work, and appearing this way really hurts us.

This passage resonates with me, but I also know it is not as simple as she makes it sound. Creating a structure where people can meaningfully contribute to a project with only small amounts of time takes a lot of work. But it seems clear that the benefits could be huge.

I think looking to tasks beyond coding can be a big benefit here. Every sort of task is different in terms of what it requires to do it well – and I think the more ways we can create for people to contribute, the more people will be able to contribute.

The context: working groups

Let me back up and give a bit of context. Earlier, I mentioned that the compiler has been changing up the way that we work, with the goal of making it much easier to get involved in developing rustc. A big part of that work has been introducing the idea of a working group.

A working group is basically an (open-ended, dynamic) set of people working towards a particular goal. These days, whenever the compiler team kicks off a new project, we create an associated working group, and we list that group (and its associated Zulip stream) on the compiler-team repository. There is also a central calendar that lists all the group meetings and so forth. This makes it pretty easy to quickly see what’s going on.

Working groups as a way into the compiler

Working groups provide an ideal vector to get involved with the compiler. For one thing, they give people a more approachable target – you’re not working on “the entire compiler”, you’re working towards a particular goal. Each of your PRs can then be building on a common part of the code, making it easier to get started. Moreover, you’re working with a smaller group of people, many of whom are also just starting out. This allows people to help one another and form a community.

Running a working group is a big job

The thing is, running a working group can be quite a big job – particularly a working group that aims to incorporate a lot of contributors. Traditionally, we’ve thought of a working group as having a lead – maybe, at best, two leads – and a bunch of participants, most of whom are being mentored:

+-------------+

| Lead(s) |

| |

+-------------+

+--+ +--+ +--+ +--+ +--+ +--+

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

+--+ +--+ +--+ +--+ +--+ +--+

| |

+--------------------------------+

(participants)

Now, if all these participants are all being mentored to write code, that means that the set of jobs that fall on the leads is something like this:

- Running the meeting

- Taking and posting minutes from the meeting

- Figuring out the technical design

- Writing the big, complex PRs that are hard to mentor

- Writing the design documents

- Writing mentoring instructions

- Writing summary blog posts and trying to call attention to what’s going on

- Synchronizing with the team at large to give status updates etc

- Being a “point of contact” for questions

- Helping contributors debug problems

- Triaging bugs and ensuring that the most important ones are getting fixed

- …

Is it any wonder that the vast majority of working group leads have full-time, paid employees? Or, alternatively, is it any wonder that often many of those tasks just don’t get done?

(Consider the NLL working group – there, we had both Felix and I working as full-time leads, essentially. Even so, we had a hard time writing out design documents, and there were never enough summary blog posts.)

Running a working group is really a lot of smaller jobs

The more I think about it, the more I think the flaw is in the way we’ve talked about a “lead”. Really, “lead” for us was mostly a kind of shorthand for “do whatever needs doing”. I think we should be trying to get more precise about what those things are, and then that we should be trying to split those roles out to more people.

For example, how awesome would it be if major efforts had some people who were just trying to ensure that the design was documented – working on rustc-guide chapters, for example, showing the major components and how they communicated. This is not easy work. It requires a pretty detailed technical understanding. It does not, however, really require writing the PRs in question – in fact, ideally, it would be done by different people, which ensures that there are multiple people who understand how the code works.

There will still be a need, I suspect, for some kind of “lead” who is generally overseeing the effort. But, these days, I like to think of it in a somewhat less… hierarchical fashion. Perhaps “organizer” is the right term. I’m not sure.

Each job is different

Going back to Jessica Lord’s post, she continues:

We need everything we can get and are thankful for all that you can contribute whether it is two hours a week, one logo a year, or a copy-edit twice a year.

Looking over the list of tasks that are involved in running a working-group, it’s interesting how many of them have distinct time profiles. Coding, for example, is a pretty intensive activity that can easily take a kind of “unbounded” amount of time, which is something not everyone has available. But consider the job of running a weekly sync meeting.

Many working groups use short, weekly sync meetings to check up on progress and to keep everything progressing. It’s a good place for newcomers to find tasks, or to triage new bugs and make sure they are being addressed. One easy, and self-contained, task in a working group might be to run the weekly meetings. This could be as simple as coming onto Zulip at the right time, pinging the right people, and trying to walk through the status updates and take some minutes. However, it might also get more complex – e.g., it might involve doing some pre-triage to try and shape up the agenda.

But note that, however you do it, this task is relatively time-contained – it occurs at a predictable point in the week. It might be a way for someone to get involved who has a fixed hole in their schedule, but can’t afford the more open-ended, coding tasks.

Just as important as code

In my last quote from Jessica Lord’s post, I left out the last sentence from the paragraph. Let me give you the paragraph in full (emphasis mine):

We need everything we can get and are thankful for all that you can contribute whether it is two hours a week, one logo a year, or a copy edit twice a year. You, too, are a first class open source citizen.

I think this is a pretty key point. I think it’s important that we recognize that working on the compiler is more than coding – and that we value those tasks – whether they be organizational tasks, writing documentation, whatever – equally.

I am worried that if we had working groups where some people are writing the code and there is somebody else who is “only” running the meetings, or “only” triaging bugs, or “only” writing design docs, that those people will feel like they are not “real” members of the working group. But to my mind they are equally essential, if not more essential. After all, it’s a lot easier to find people who will spend their free time writing PRs than it is to find people who will help to organize a meeting.

Growing the compiler team

The point of this post, in case you missed it, is that I would like to grow our conception of the compile team beyond coders. I think we should be actively recruiting folks with a lot of different skill sets and making them full members of the compiler team:

- organizers and project managers

- documentation authors

- code evangelists

I’m not really sure what this full set of roles should be, but I know that the compiler team cannot function without them.

Beyond the compiler team

One other note: I think that when we start going down this road, we’ll find that there is overlap between the “compiler team” and other teams in the rust-lang org. For example, the release team already does a great job of tracking and triaging bugs and regressions to help ensure the overall quality of the release. But perhaps the compiler team also wants to do its own triaging. Will this lead to a “turf war”? Personally, I don’t really see the conflict here.

One of the beauties of being an open-source community is that we don’t need to form strict managerial hierarchies. We can have the same people be members of both the release team and the compiler team. As part of the release team, they would presumably be doing more general triaging and so forth; as part of the compiler team, they would be going deeper into rustc. But still, it’s a good thing to pay attention to. Maybe some things don’t belong in the compiler-team proper.

Conclusion

I don’t quite a have a call to action here, at least not yet. This is still a WIP – we don’t know quite the right way to think about these non-coding roles. I think we’re going to be figuring that out, though, as we gain more experience with working groups.

I guess I can say this, though: If you are a project manager or a tech writer, and you think you’d like to get more deeply involved with the compiler team, now’s a good time. =) Start attending our steering meetings, or perhaps the weekly meetings of the meta working group, or just ping me over on the rust-lang Zulip.

http://smallcultfollowing.com/babysteps/blog/2019/04/15/more-than-coders/

|

|

Alex Gibson: My sixth year working at Mozilla |

This week marks my sixth year working at Mozilla! I’ll be honest, this year’s mozillaversary came by so fast I nearly forgot all about writing this blog post. It feels hard to believe that I’ve been working here for a full six years. I’ve guess grown and learned a lot in that time, but it still doesn’t feel like all that long ago when I first joined full time. Years start to blur together. So, what’s happened in this past 12 months?

Building a design system

Mozilla’s website design system, named Protocol, is now a real product. You can install it via NPM and build on-brand Mozilla web pages using its compenents. Protocol builds on a system of atoms, molecules, and organiams, following the concepts first made popular in Atomic Web Design. Many of the new design system components can be seen in use on the recently redesigned www.mozilla.org pages.

It was fun to help get this project off the ground, and to see it finally in action on a live website. Making a flexible, intuitive design system is not easy, and we learned a lot in the first year of the project that can help us to improve Protocol over the coming months. By the end of the year, our hope is to have fully ported all mozilla.org content to use Protocol. This is not an easy task for a small team and a large website that’s been around for over a decade. It’ll be an interesting challenge!

Measuring clicks to installs

Supporting the needs of experimentation on Firefox download pages is something that our team has been helping to manage and facilitate for several years now. The breadth of data now required in order to fully understand the effectiveness of experiments is a lot more complex today compared to when we first started. Product retention (i.e. how often people actively use Firefox) is now the key metric of success. Measuring how many clicks a download button on a web page receives is relatively straight forward, but understanding how many of those people go on to actually run the installer, and then how often they end up actively using the product for requires a multi-step funnel of measurement. Our team has continued to help build custom tools to facilitate this kind of data in experimentation, so that we can make better informed product decisions.

Publishing systems

One of our team’s main objectives is to enable people at Mozilla to publish quality content to the web quickly and easily, whether that be on mozilla.org, a microsite, or on a official blog. We’re a small team however, and the marketing organisation has a great appetite for wanting new content at a fast pace. This was one of the (many) reasons why we invested in building a design system, so that we can create on-brand web pages at a faster pace with less repetitive manual work. We also invested in building more custom publishing systems, so that other teams can work more independently. We’ve long had publishing systems in place for things like Firefox release notes, and now we also have some initial systems in place for publishing marketing content, such as the what can currently be seen on the mozilla.org homepage.

Individual contributions

- I made over 167 commits to bedrock this past year.

- I made over 78 commits to protocol this past year.

- We moved to GitHub issues for most of our projects over the past year, so my Bugzilla usage has dropped. But I’ve now filed over 534 bugs, made over 5185 comments, and been assigned more than 656 bugs on Bugzilla in total. Yikes.

Travel

I got to visit Portland, San Fransisco for Mozilla’s June all-hands event, and also Orlando for December’s all-hands. I brought the family along to Disney World for an end-of-year vacation afterwards, who all had an amazing time. We’re very lucky!

https://alxgbsn.co.uk/2019/04/15/my-sixth-year-working-at-mozilla/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: How to curl up 2020? |

We’re running a short poll asking people about where and how we should organize curl up 2020 – our annual curl developers conference. I’m not making any promises, but getting people’s opinions will help us when preparing for next year.

I’ll leave the poll open for a couple of days so please respond asap.

|

|

Asa Dotzler: My New Role at Mozilla |

Several months ago I took on a new role at Mozilla, product manager for Firefox browser accessibility. I couldn’t be more excited about this. It’s an area I’ve been interested in for nearly my entire career at Mozilla.

It was way back in 2000, after talking with Aaron Leventhal at a Netscape/Mozilla developer event, that I first started thinking about accessibility in Mozilla products and how well the idea of inclusivity fit with some my personal reasons for working on the Mozilla project. If I remember correctly, Aaron was working on a braille reader or similar assistive technologies and he was concerned that the new Mozilla browser, which used a custom UI framework, wasn’t accessible to that assistive technology. Aaron persisted and Mozilla browser technologies became some of the most accessible available.

Thanks in big part to Aaron’s advocacy, hacking, and other efforts over many years, accessibility became “table stakes” for Mozilla applications. The browsers we shipped over the years were always designed for everyone and “accessible to all” came to the Mozilla Mission.

Our mission is to ensure the Internet is a global public resource, open and accessible to all. An Internet that truly puts people first, where individuals can shape their own experience and are empowered, safe and independent.

I’m excited to be working on something so directly tied to Mozilla’s core values. I’m also super-excited to be working with so many great Firefox teams, and in particular the Firefox Accessibility Engineering team, who have been doing amazing work on Firefox’s accessibility features for many years.

I’m still just getting my feet wet, and I’ve got a lot more to learn. Stay tuned to this space for the occasional post around my new role with a focus on our efforts to ensure that Firefox is the best experience possible for people with disabilities. I expect to write at least monthly updates as we prioritize, fix, test and ship improvements to our core accessibility features like keyboard navigation, screen reader support, high contrast mode, narration, and the accessibility inspector and auditors, etc.

|

|

Francois Marier: Secure ssh-agent usage |

ssh-agent was in the news recently due to the matrix.org

compromise. The main

takeaway from that incident was that one should avoid the ForwardAgent

(or -A) functionality when ProxyCommand can

do

and consider multi-factor authentication on the server-side, for example

using

libpam-google-authenticator

or libpam-yubico.

That said, there are also two options to ssh-add that can help reduce the

risk of someone else with elevated privileges hijacking your agent to make

use of your ssh credentials.

Prompt before each use of a key

The first option is -c which will require you to confirm each use of your

ssh key by pressing Enter when a graphical prompt shows up.

Simply install an ssh-askpass frontend like

ssh-askpass-gnome:

apt install ssh-askpass-gnome

and then use this to when adding your key to the agent:

ssh-add -c ~/.ssh/key

Automatically removing keys after a timeout

ssh-add -D will remove all identities (i.e. keys) from your ssh agent, but

requires that you remember to run it manually once you're done.

That's where the second option comes in. Specifying -t when adding a key

will automatically remove that key from the agent after a while.

For example, I have found that this setting works well at work:

ssh-add -t 10h ~/.ssh/key

where I don't want to have to type my ssh password everytime I push a git branch.

At home on the other hand, my use of ssh is more sporadic and so I don't mind a shorter timeout:

ssh-add -t 4h ~/.ssh/key

Making these options the default

I couldn't find a configuration file to make these settings the default and

so I ended up putting the following line in my ~/.bash_aliases:

alias ssh-add='ssh-add -c -t 4h'

so that I can continue to use ssh-add as normal and have not remember

to include these extra options.

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: Test servers for curl |

curl supports some twenty-three protocols (depending on exactly how you count).

In order to properly test and verify curl’s implementations of each of these protocols, we have a test suite. In the test suite we have a set of handcrafted servers that speak the server-side of these protocols. The more used a protocol is, the more important it is to have it thoroughly tested.

We believe in having test servers that are “stupid” and that offer buttons, levers and thresholds for us to control and manipulate how they act and how they respond for testing purposes. The control of what to send should be dictated as much as possible by the test case description file. If we want a server to send back a slightly broken protocol sequence to check how curl supports that, the server must be open for this.

In order to do this with a large degree of freedom and without restrictions, we’ve found that using “real” server software for this purpose is usually not good enough. Testing the broken and bad cases are typically not easily done then. Actual server software tries hard to do the right thing and obey standards and protocols, while we rather don’t want the server to make any decisions by itself at all but just send exactly the bytes we ask it to. Simply put.

Of course we don’t always get what we want and some of these protocols are fairly complicated which offer challenges in sticking to this policy all the way. Then we need to be pragmatic and go with what’s available and what we can make work. Having test cases run against a real server is still better than no test cases at all.

Now SOCKS

“SOCKS is an Internet protocol that exchanges network packets between a client and server through a proxy server. Practically, a SOCKS server proxies TCP connections to an arbitrary IP address, and provides a means for UDP packets to be forwarded.

(according to Wikipedia)

Recently we fixed a bug in how curl sends credentials to a SOCKS5 proxy as it turned out the protocol itself only supports user name and password length of 255 bytes each, while curl normally has no such limits and could pass on credentials with virtually infinite lengths. OK, that was silly and we fixed the bug. Now curl will properly return an error if you try such long credentials with your SOCKS5 proxy.

As a general rule, fixing a bug should mean adding at least one new test case, right? Up to this time we had been testing the curl SOCKS support by firing up an ssh client and having that setup a SOCKS proxy that connects to the other test servers.

curl -> ssh with SOCKS proxy -> test server

Since this setup doesn’t support SOCKS5 authentication, it turned out complicated to add a test case to verify that this bug was actually fixed.

This test problem was fixed by the introduction of a newly written SOCKS proxy server dedicated for the curl test suite (which I simply named socksd). It does the basic SOCKS4 and SOCKS5 protocol logic and also supports a range of commands to control how it behaves and what it allows so that we can now write test cases against this server and ask the server to misbehave or otherwise require fun things so that we can make really sure curl supports those cases as well.

It also has the additional bonus that it works without ssh being present so it will be able to run on more systems and thus the SOCKS code in curl will now be tested more widely than before.

curl -> socksd -> test server

Going forward, we should also be able to create even more SOCKS tests with this and make sure to get even better SOCKS test coverage.

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2019/04/13/test-servers-for-curl/

|

|

Firefox UX: Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt: Part 3 |

Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt

Part 3: Implementation & governance

Summary: This series outlines the process to diagnose, treat, and manage enterprise content debt, using Firefox add-ons as a case study. Part 1 frames the Firefox add-ons space in terms of enterprise content debt. Part 2 lists the eight steps to develop a new content model. This final piece describes the deliverables we created to support that new model.

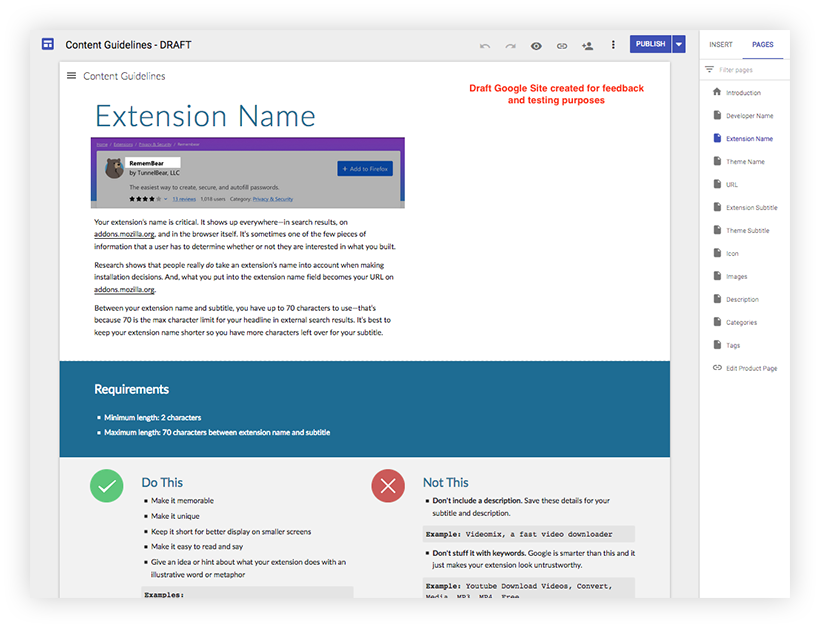

Content guidelines for the “author experience”

“Just as basic UX principles tell us to help users achieve tasks without frustration or confusion, author experience design focuses on the tasks and goals that CMS users need to meet — and seeks to make it efficient, intuitive, and even pleasurable for them to do so.” — Sara Wachter-Boettcher, Content Everywhere

A content model is a useful tool for organizations to structure, future-proof, and clean up their content. But that content model is only brought to life when content authors populate the fields you have designed with actual content. And the quality of that content is dependent in part on how the content system supports those authors in their endeavor.

We had discovered through user research that developers create extensions for a great variety of reasons — including as a side hobby or for personal enjoyment. They may not have the time, incentive, or expertise to produce high-quality, discoverable content to market their extensions, and they shouldn’t be expected to. But, we can make it easier for them to do so with more actionable guidelines, tools, and governance.

An initial review of the content submission flow revealed that the guidelines for developers needed to evolve. Specifically, we needed to give developers clearer requirements, explain why each content field mattered and where that content showed up, and provide them with examples. On top of that, we needed to give them writing exercises and tips when they hit a dead end.

So, to support our developer authors in creating our ideal content state, I drafted detailed content guidelines that walked extension developers through the process of creating each content element.

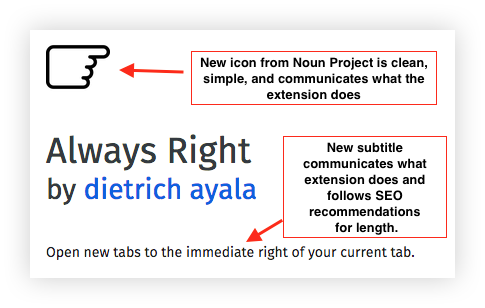

Once a draft was created, we tested it with Mozilla extension developer, Dietrich Ayala. Dietrich appreciated the new guidelines, and more importantly, they helped him create better content.

We also conducted interviews with a cohort of developers in a related project to redesign the extensions submission flow (i.e., the place in which developers create or upload their content). As part of that process, we solicited feedback from 13 developers about the new guidelines:

- Developers found the guidelines to be helpful and motivating for improving the marketing and SEO of their extensions, thereby better engaging users.

- The clear “do this/not that” section was very popular.

- They had some suggestions for improvement, which were incorporated into the next version.

Excerpts from developer interviews:

“If all documentation was like this, the world would be a better place…It feels very considered. The examples of what to do, what not do is great. This extra mile stuff is, frankly, something I don’t see on developer docs ever: not only are we going to explain what we want in human language, but we are going to hold your hand and give you resources…It’s [usually] pulling teeth to get this kind of info [for example, icon sizes] and it’s right here. I don’t have to track down blogs or inscrutable documentation.”

“…be more upfront about the stuff that’s possible to change and the stuff that would have consequences if you change it.”

Finally, to deliver the guidelines in a useful, usable format, we partnered with the design agency, Turtle, to build out a website.

Bringing the model to life

Now that the guidelines were complete, it was time to develop the communication materials to accompany the launch.

To bring the content to life, and put a human face on it, we created a video featuring our former Director of Firefox UX, Madhava Enros, and an extension developer. The video conveys the importance of creating good content and design for product pages, as well as how to do it.

Preliminary results

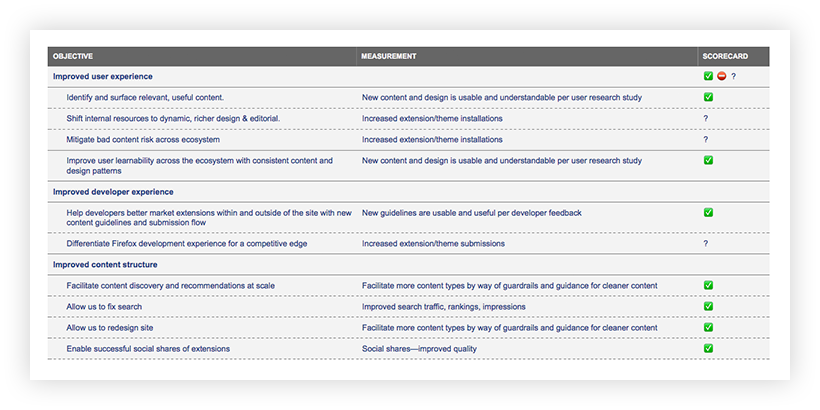

Our content model had a tall order to fill, as detailed in our objectives and measurements template.

So, how did we do against those objectives? While the content guidelines have not yet been published by the time of this blog post, here’s a snapshot of preliminary results:

And, for illustration, some examples in action:

1. Improved Social Share Quality

2. New Google search snippet model reflective of SEO best practices and what we’d learned from user research — such as the importance of social proof via extension ratings.

3. Promising, but early, SEO findings:

- Organic search traffic decline slowed down by 2x compared to summer 2018.

- Impressions in search for the AMO site are much higher (30%) than before. Shows potential of the domain.

- Overall rankings are stable, and top 10 rankings are a bit up.

- Extension/theme installs via organic search are stable after previous year declines.

- Conversion rate to installs via organic search are growing, from 42% to 55%.

Conclusion & resources

There’s isn’t a quick or easy fix to enterprise content debt, but investing the time and energy to think about your content as structured data, to cultivate a content model based upon your business goals, and develop the guidance and guardrails to realize that model with your content authors, pays dividends in the long haul.

Hopefully this series has provided a series of steps and tools to figure out your individual payment plan. For more on this topic:

- Content Everywhere: Strategy and Structure For Future-Ready Content by Sara Wachter-Boettcher

- Managing Enterprise Content: A Unified Content Strategy by Ann Rockley

- “Content debt: What it is, where to find it, and how to prevent it in the first place” by Melody Kramer

And, if you need more help, and you’re fortunate enough to have a content strategist on your team, you can always ask that friendly content nerd for some content credit counseling.

Thank you to Michelle Heubusch, Jennifer Davidson, Emanuela Damiani, Philip Walmsley, Kev Needham, Mike Conca, Amy Tsay, Jorge Villalobos, Stuart Colville, Caitlin Neiman, Andreas Wagner, Raphael Raue, and Peiying Mo for their partnership in this work.

Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt: Part 3 was originally published in Firefox User Experience on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

Firefox UX: Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt: Part 2 |

Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt

Part 2: Developing Solutions

Summary: This series outlines the process to diagnose, treat, and manage enterprise content debt, using Firefox add-ons as a case study. In Part 1 , I framed the Firefox add-ons space in terms of an enterprise content debt problem. In this piece, I walk through the eight steps we took to develop solutions, culminating in a new content model. See Part 3 for the deliverables we created to support that new model.

- Step 1: Stakeholder interviews

- Step 2: Documenting content elements

- Step 3: Data analysis — content quality

- Step 4: Domain expert review

- Step 5: Competitor compare

- Step 6: User research — What content matters?

- Step 7: Creating a content model

- Step 8: Refine and align

Step 1: Stakeholder interviews

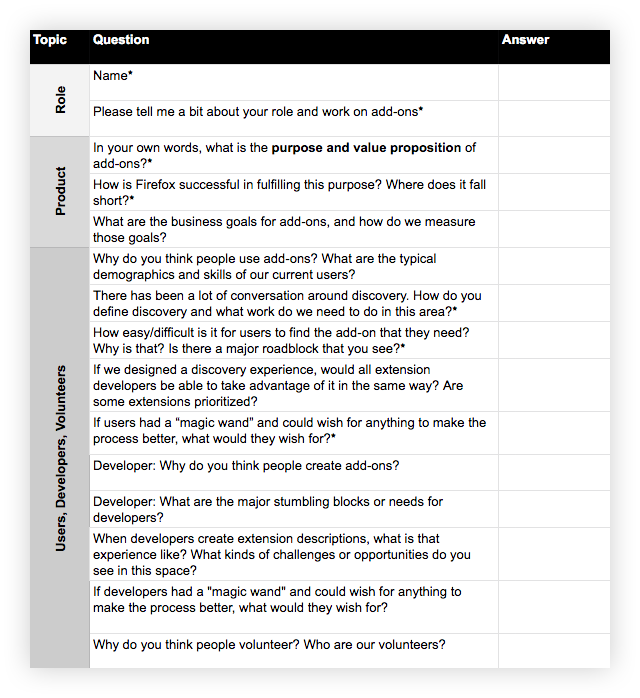

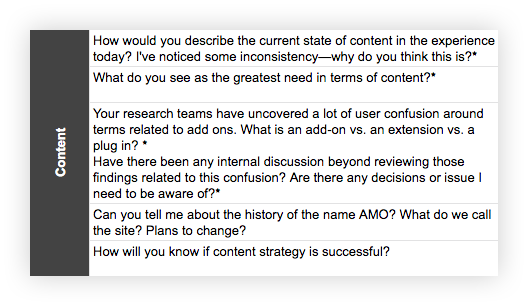

To determine a payment plan for our content debt, we needed to first get a better understanding of the product landscape. Over the course of a couple of weeks, the team’s UX researcher and I conducted stakeholder interviews:

Who: Subject matter experts, decision-makers, and collaborators. May include product, engineering, design, and other content folks.

What: Schedule an hour with each participant. Develop a spreadsheet with questions that get at the heart of what you are trying to understand. Ask the same set of core questions to establish trends and patterns, as well as a smaller set specific to each interviewee’s domain expertise.

After completing the interviews, we summarized the findings and walked the team through them. This helped build alignment with our stakeholders around the issues and prime them for the potential UX and content solutions ahead.

Stakeholder interviews also allowed us to clarify our goals. To focus our work and make ourselves accountable to it, we broke down our overarching goal — improve Firefox users’ ability to discover, trust, install, and enjoy extensions — into detailed objectives and measurements using an objectives and measurements template. Our main objectives fell into three buckets: improved user experience, improved developer experience, and improved content structure. Once the work was done, we could measure our progress against those objectives using the measurements we identified.

Step 2: Documenting content elements

Product environment surveyed, we dug into the content that shaped that landscape.

Extensions are recommended and accessed not only through AMO, but in a variety of places, including the Firefox browser itself, in contextual recommendations, and in external content. To improve content across this large ecosystem, we needed to start small…at the cellular content level. We needed to assess, evolve, and improve our core content elements.

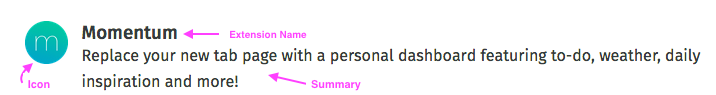

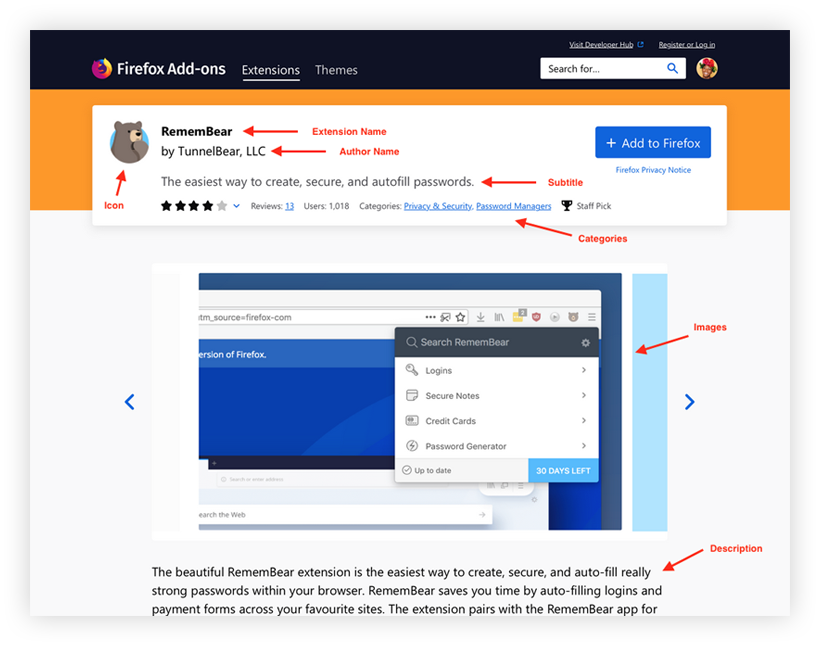

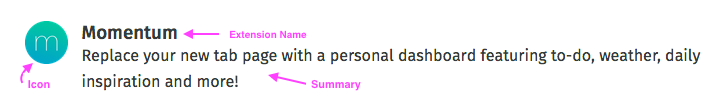

By “content elements,” I mean all of the types of content or data that are attached to an extension — either by developers in the extension submission process, by Mozilla on the back-end, or by users. So, very specifically, these are things like description, categories, tags, ratings, etc. For example, the following image contains three content elements: icon, extension name, summary:

Using Excel, I documented existing content elements. I also documented which elements showed up where in the ecosystem (i.e., “content touchpoints”):

The content documentation Excel served as the foundational document for all the work that followed. As the team continued to acquire information to shape future solutions, we documented those learnings in the Excel, evolving the recommendations as we went.

Step 3: Data analysis — content quality

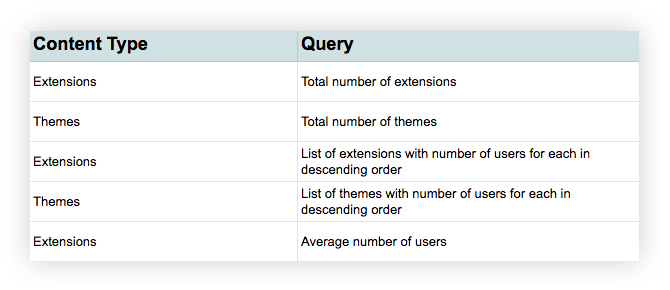

Current content elements identified, we could now assess the state of said content. To complete this analysis, we used a database query (created by our product manager) that populated all of the content for each content element for every extension and theme. Phew.

We developed a list of queries about the content…

…and then answered those queries for each content element field.

- For quantitative questions (like minimum/maximum content length per element), we used Excel formulas.

- For questions of content quality, we analyzed a sub-section of the data. For example, what’s the content quality state of extension names for the top 100 extensions? What patterns, good and bad, do we see?

Step 4: Domain expert review

I also needed input from domain experts on the content elements, including content reviewers, design, and localization. Through this process, we discovered pain points, areas of opportunity, and considerations for the new requirements.

For example, we had been contemplating a 10-character minimum for our long description field. Conversations with localization expert, Peiying Mo, revealed that this would not work well for non-English content authors…while 10 characters is a reasonable expectation in English, it’s asking for quite a bit of content when we are talking about 10 Chinese characters.

Because improving search engine optimization (SEO) for add-ons was a priority, review by SEO specialist, Raphael Raue, was especially important. Based on user research and analytics, we knew users often find extensions, and make their way to the add-ons site, through external search engines. Thus, their first impression of an add-on, and the basis upon which they may assess their interest to learn more, is an extension title and description in Google search results (also called a “search snippet”). So, our new content model needed to be optimized for these search listings.

Step 5: Competitor compare

A picture of the internal content issues and needs was starting to take shape. Now we needed to look externally to understand how our content compared to competitors and other successful commercial sites.

Philip Walmsley, UX designer, identified those sites and audited their content elements, identifying surplus, gaps, and differences from Firefox. We discussed the findings and determined what to add, trim, or tweak in Firefox’s content element offerings depending on value to the user.

Step 6: User research — what content matters?

A fair amount of user research about add-ons had already been done before we embarked on this journey, and Jennifer Davidson, our UX researcher, lead additional, targeted research over the course of the year. That research informed the content element issues and needs. In particular, a large site survey, add-ons team think-aloud sessions, and in-person user interviews identified how users discover and decide whether or not to get an extension.

Regarding extension product pages in particular, we asked:

- Do participants understand and trust the content on the product pages?

- What type of information is important when deciding whether or not to get an extension?

- Is there content missing that would aid in their discovery and comprehension?

Through this work, we deepened our understanding of the relative importance of different content elements (for example: extension name, summary, long description were all important), what elements were critical to decision making (such as social proof via ratings), and where we had content gaps (for example, desire for learning-by-video).

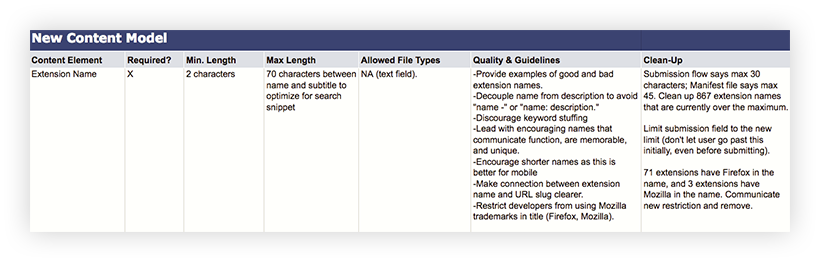

Step 7: Creating a content model

“…content modeling gives you systemic knowledge; it allows you to see what types of content you have, which elements they include, and how they can operate in a standardized way — so you can work with architecture, rather than designing each one individually.” — Sara Wachter-Boettcher, Content Everywhere, 31

Learnings from steps 1–6 informed the next, very important content phase: identifying a new content model for an add-ons product page.

A content model defines all of the content elements in an experience. It details the requirements and restrictions for each element, as well as the connections between elements. Content models take diverse shapes and forms depending on project needs, but the basic steps often include documentation of the content elements you have (step 2 above), analysis of those elements (steps 3–6 above), and then charting new requirements based on what you’ve learned and what the organization and users need.

Creating a content model takes quite a bit of information and input upfront, but it pays dividends in the long-term, especially when it comes to addressing and preventing content debt. The add-ons ecosystem did not have a detailed, updated content model and because of that, developers didn’t have the guardrails they needed to create better content, the design team didn’t have the content types it needed to create scalable, user-focused content, and users were faced with varying content quality.

A content model can feel prescriptive and painfully detailed, but each content element within it should provide the flexibility and guidance for content creators to produce content that meets their goals and the goals of the system.

Step 8: Refine and align

Now that we had a draft content model — in other words, a list of recommended requirements for each content element — we needed review and input from our key stakeholders.

This included conversations with add-ons UX team members, as well as partners from the initial stakeholder interviews (like product, engineering, etc.). It was especially important to talk through the content model elements with designers Philip and Emanuela, and to pressure test whether each new element’s requirements and file type served design needs across the ecosystem. One of the ways we did this was by applying the new content elements to future designs, with both best and worst-case content scenarios.

[caption id=”attachment_4182" align=”aligncenter” width=”820"]

Based on this review period and usability testing on usertesting.com, we made adjustments to our content model.

Okay, content model done. What’s next?

Now that we had our new content model, we needed to make it a reality for the extension developers creating product pages.

In Part 3, I walk through the creation and testing of deliverables, including content guidelines and communication materials.

Thank you to Michelle Heubusch, Jennifer Davidson, Emanuela Damiani, Philip Walmsley, Kev Needham, Mike Conca, Amy Tsay, Jorge Villalobos, Stuart Colville, Caitlin Neiman, Andreas Wagner, Raphael Raue, and Peiying Mo for their partnership in this work.

Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt: Part 2 was originally published in Firefox User Experience on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

Firefox UX: Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt: Part 1 |

Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt

Part 1: Framing the problem

Summary: This series outlines the process to diagnose, treat, and manage enterprise content debt, using Firefox add-ons as a case study. This first part frames the enterprise content debt issue. Part 2 lists the eight steps to develop a new content model. Part 3 describes the deliverables we created to support that new model.

Background

If you want to block annoying ads or populate your new tab with sassy cats, you can do it…with browser extensions and themes. Users can download thousands of these “add-ons” from Firefox’s host site, addons.mozilla.org (“AMO”), to customize their browsing experience with new functionality or a dash of whimsy.

Add-ons can be a useful and delightful way for people to improve their web experience — if they can discover, understand, trust, and appreciate their offerings. Over the last year, the add-ons UX pod at Firefox, in partnership with the larger add-ons team, worked on ways to do just that.

One of the ways we did this was by looking at these interconnected issues through the lens of content structure and quality. In this series, I’ll walk you through the steps we took to develop a new content model for the add-ons ecosystem.

Understanding the problem

Add-ons are largely created by third-party developers, who also create the content that describes the add-ons for users. That content includes things like extension name, icon, summary, long, description, screenshots, etcetera:

With 10,000+ extensions and 400,000+ themes, we are talking about a lot of content. And while the add-ons team completely appreciated the value of the add-ons themselves, we didn’t really understand how valuable the content was, and we didn’t use it to its fullest potential.

The first shift we made was recognizing that what we had was enterprise content — structured content and metadata stored in a formal repository, reviewed, sometimes localized, and published in different forms in multiple places.

Then, when we assessed the value of it to the enterprise, we uncovered something called content debt.

Content debt is the hidden cost of not managing the creation, maintenance, utility, and usability of digital content. It accumulates when we don’t treat content like an asset with financial value, when we value expediency over the big picture, and when we fail to prioritize content management. You can think of content debt like home maintenance. If you don’t clean your gutters now, you’ll pay in the long term with costly water damage.

AMO’s content debt included issues of quality (missed opportunities to communicate value and respond to user questions), governance (varying content quality with limited organizational oversight), and structure (the need for new content types to evolve site design and improve social shares and search descriptions).

A few examples of content debt in action:

All of this equals quite a bit of content debt that prevents developers and users from being as successful as they could be in achieving their interconnected goals: offering and obtaining extensions. It also hinders the ecosystem as a whole when it comes to things like SEO (Search Engine Optimization), which the team wanted to improve.

Given the AMO site’s age (15 years), and the amount of content it contains, debt is to be expected. And it’s rare for a content strategist to be given a content challenge that doesn’t involve some debt because it’s rare that you are building a system completely from scratch. But, that’s not the end of the story.

When we considered the situation from a systems-wide perspective, we realized that we needed to move beyond thinking of the content as something created by an individual developer in a vacuum. Yes, the content is developer-generated — and with that a certain degree of variation is to be expected — but how could we provide developers with the support and perspective to create better content that could be used not only on their product page, but across the content ecosystem? While the end goal is more users with more extensions by way of usable content, we needed to create the underpinning rules that allowed for that content to be expressed across the experience in a successful way.

In part 2, I walk through the specific steps the team took to diagnose and develop solutions for our enterprise content debt. Meanwhile, speaking of the team…

Meet our ‘UX supergroup’

“A harmonious interface is the product of functional, interdisciplinary communication and clear, well-informed decision making.” — Erika Hall, Conversational Design, 108

While the problem space is framed in terms of content strategy, the diagnosis and solutions were very much interdisciplinary. For this work, I was fortunate to be part of a “UX supergroup,” i.e., an embedded project team that included a user researcher (Jennifer Davidson), a designer with strength in interaction design (Emanuela Damiani), a designer with strength in visual design (Philip Walmsley), and a UX content strategist (me).

We were able to do some of our best work by bringing to bear our discipline-specific expertise in an integrated and deeply collaborative way. Plus, we had a mascot — Pusheen the cat — inspired in part by our favorite tab-changing extension, Tabby Cat.

See Part 2, Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt: Developing Solutions

Thank you to Michelle Heubusch, Jennifer Davidson, Emanuela Damiani, Philip Walmsley, Kev Needham, Mike Conca, Amy Tsay, Jorge Villalobos, Stuart Colville, Caitlin Neiman, Andreas Wagner, Raphael Raue, and Peiying Mo for their partnership in this work.

Paying Down Enterprise Content Debt: Part 1 was originally published in Firefox User Experience on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

|

|

Mozilla VR Blog: Firefox Reality 1.1.3 |

Firefox Reality 1.1.3 will soon be available for all users in the Viveport, Oculus, and Daydream app stores.

This release includes some major new features including support for 6DoF controllers, new environments, a curved browser window option and some bug fixes.

Highlights:

- Improved support for 6DoF Oculus controllers and user height.

- Added support for 6DoF VIVE Focus (WaveVR) controllers.