Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

The Mozilla Blog: Welcome Lindsey Shepard, VP Product Marketing |

I’m excited to let you know that today, Lindsey Shepard joins us as our VP of Product Marketing.

Lindsey brings a wealth of experience from a variety of sectors ranging from consumer technology to the jewelry industry.

“I’m thrilled to be joining Mozilla, an organization that has always been a champion for user agency and data privacy, during this pivotal time in the tech industry. I’m looking forward to showcasing to people the iconic Firefox brand, along with its quickly-expanding offering of products and services that realistically and respectfully meet the needs and challenges of online life today.”

Most recently, Lindsey headed up corporate-level marketing for Facebook Inc., including leading product marketing for Facebook’s core products: News Feed, News, Stories, Civic Engagement, Privacy and Safety. Before joining Facebook, Lindsey led marketing at GoldieBlox, a Bay Area start-up focused on bridging the gender gap in STEM.

As our new VP of Product Marketing Lindsey will be a core member of my marketing leadership team, responsible for building strong ties with our product organization. She will be a key driver of Mozilla’s future growth, overseeing new product launches, nurturing existing products, ideating on key campaigns and go-to-market strategies, and evangelizing new innovations in internet technologies.

Lindsey will be based in the Bay Area and will share her time between our Mountain View and San Francisco offices. Please join me in welcoming Lindsey to Mozilla.

The post Welcome Lindsey Shepard, VP Product Marketing appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2019/03/18/welcome-lindsey-shepard-vp-product-marketing/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: A Homepage for the JavaScript Specification |

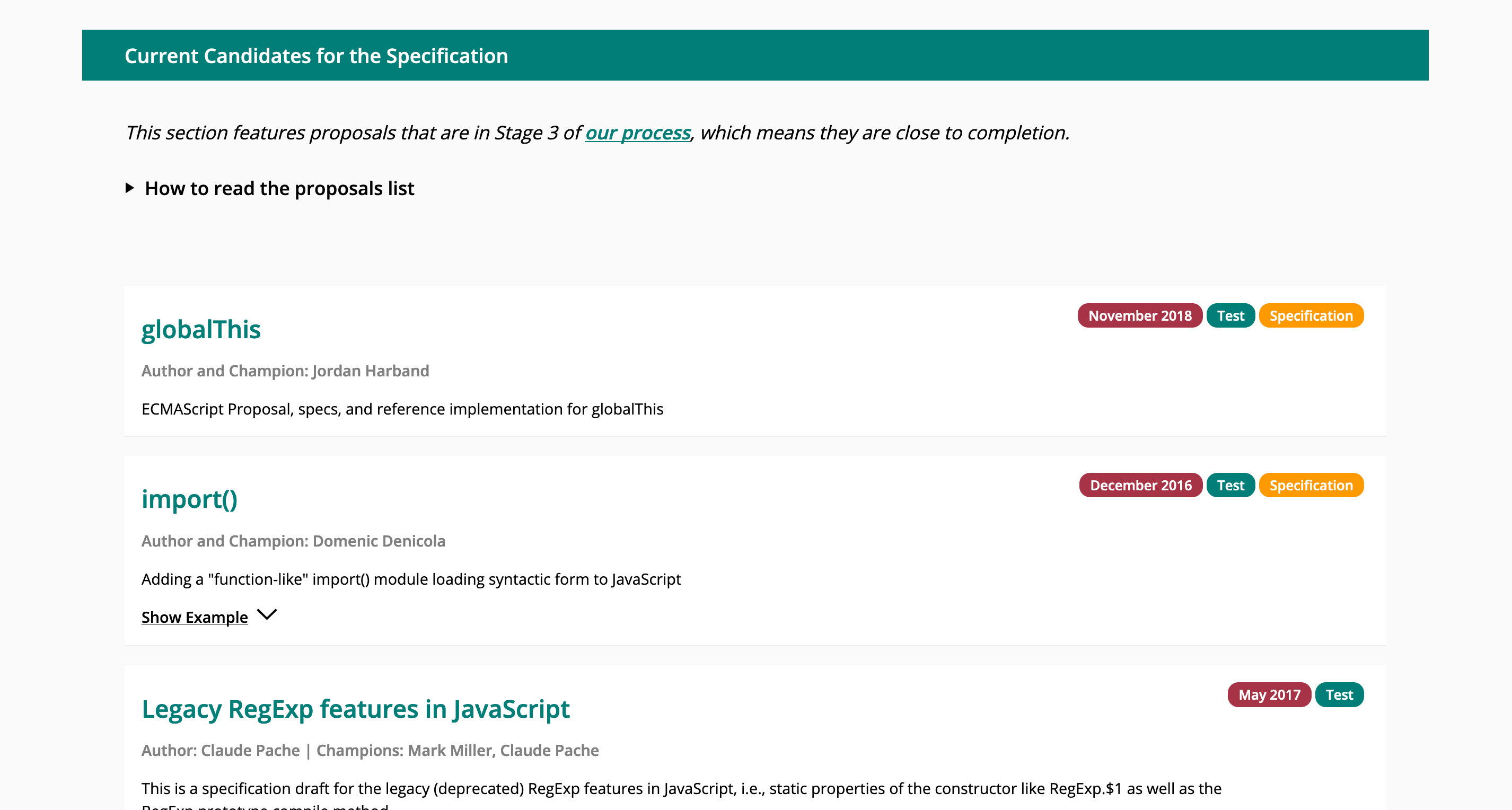

Screenshot of the TC39 website

Ecma TC39, the JavaScript Standards Committee, is proud to announce that we have shipped a website for following updates to the JavaScript specification. This is the first part of a two-part project aimed at improving our information distribution and documentation. The website provides links to our most significant documents, as well as a list of proposals that are near completion. Our goal is to help people find the information they need in order to understand the specification and our process.

While the website is currently an MVP and very simple, we have plans to expand it. These plans include a set of documentation about how we work. We will experiment with other features as the need arises.

The website comes as part of work that began last year to better understand how the community was accessing information about the work around the JavaScript specification. We did a series of in-person interviews, followed by a widely distributed survey to better understand what people struggled with. One of the biggest requests was that we publish and maintain a website that helps people find the information they are looking for.

Resource needs

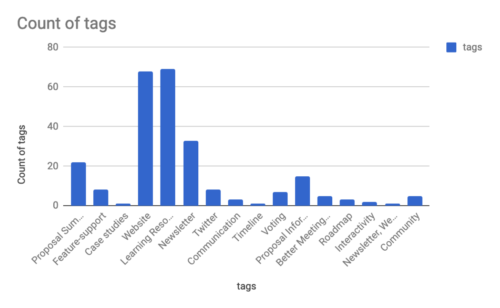

The two most requested items with regard to resources were Learning Resources and a Website. These two are linked, but require very different types of work. Since this clearly highlighted the need for a website, we began work on this right away.

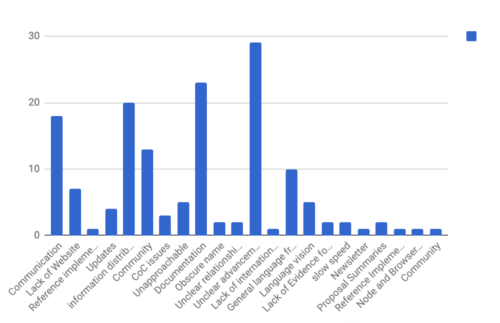

Aggregated tags in response to the question “What would you like to see as a resource for the language specification process?”

We identified different types of users: Learners who are discovering the specification for the first time, Observers of the specification who are watching proposal advancement, and Reference Users who need a central location where all of the significant documents can be found. The website was designed around these users. In order to not overwhelm people with information, the MVP is specifically focused on the most pertinent information, namely proposals in Stage 3 of our process. Links are contextualized in order to help people understand what documents they are looking at.

Stage 3 Proposal List

The website is very simple, but gives us a starting point from which to move forward. We are continuing to work on documenting our process. We hope to make more of these documents publicly available soon and to incorporate them into the website over time.

Developer frustrations

The survey surfaced a number of issues that have been impacting the community around JavaScript. Three of the top four frustrations were related to things that could be alleviated by building a website. One that was not directly related but heavily emphasized was that the unclear advancement of proposals. This was also surfaced in GitHub issues. This is challenging to resolve, but we are currently working through ideas. For the time being, we have added a link to the most recent presentation of each proposal. We also have a checklist in the TC39 Process document that is now being added to some proposals on GitHub.

Aggregated tags in response to the question “Is there something we can do better, or that you find particularly frustrating right now?”

As part of the survey, we collected emails in order to get in touch later, as we were unsure how many responses we would get. The goal was to better understand specific concerns. However, we had an overwhelming amount of feedback that pointed us in the direction we needed to go. After reviewing this, we decided against keeping this personal information and to request feedback publicly on a case-by-case basis. Thank you to everyone who participated.

We are looking forward to your feedback and comments. This project was community-driven— thank you to everyone who made it possible!

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/03/a-homepage-for-the-javascript-specification/

|

|

QMO |

Hello Mozillians,

We are happy to let you know that Friday, March 29th, we are organizing Firefox 67 Beta 6 Testday. We’ll be focusing our testing on: Anti-tracking (Fingerprinting and Cryptominers) and Media playback & support.

Check out the detailed instructions via this etherpad.

No previous testing experience is required, so feel free to join us on #qa IRC channel where our moderators will offer you guidance and answer your questions.

Join us and help us make Firefox better!

See you on Friday!

|

|

Wladimir Palant: Should you be concerned about LastPass uploading your passwords to its server? |

TL;DR: Yes, very much.

The issue

I’ve written a number of blog posts on LastPass security issues already. The latest one so far looked into the way the LastPass data is encrypted before it is transmitted to the server. The thing is: when your password manager uploads all data to its server backend, you normally want to be very certain that the data visible to the server is useless both to attackers who manage to compromise the server and company employees running that server. Early last year I reported a number of issues that allowed subverting LastPass encryption with comparably little effort. The most severe issues have been addressed, so all should be good now?

Sadly, no. It is absolutely possible for a password manager to use a server for some functionality while not trusting it. However, LastPass has been designed in a way that makes taking this route very difficult. In particular, the decision to fall back to server-provided pages for parts of the LastPass browser extension functionality is highly problematic. For example, whenever you access Account Settings you leave the trusted browser extension and access a web interface presented to you by the LastPass server, something that the extension tries to hide from you. Some other extension functionality is implemented similarly.

The glaring hole

So back in November I discovered an API meant to accommodate this context switch from the extension to a web application and make it transparent to the user. Not sure how I managed to overlook it on my previous strolls through the LastPass codebase but the getdata and keyplug2web API calls are quite something. The response to these calls contains your local encryption key, the one which could be used to decrypt all your server-side passwords.

There has been a number of reports in the past about that API being accessible by random websites. I particularly liked this security issue uncovered by Tavis Ormandy which exploited an undeclared variable to trick LastPass into loosening up its API restrictions. Luckily, all of these issues have been addressed and by now it seems that only lastpass.com and lastpass.eu domains can trigger these calls.

Oh, but the chances of some page within lastpass.com or lastpass.eu domain to be vulnerable aren’t exactly low! Somebody thought of that, so there is an additional security measure. The extension will normally ignore any getdata or keyplug2web calls, only producing a response once after this feature is unlocked. And it is unlocked on explicit user actions such as opening Account Preferences. This limits the danger considerably.

Except that the action isn’t always triggered by the user. There is a “breach notification” feature where the LastPass server will send notifications with arbitrary text and link to the user. If the user clicks the link here, the keyplug2web API will be unlocked and the page will get access to all of the user’s passwords.

The attack

LastPass is run by LogMeIn, Inc. which is based in United States. So let’s say the NSA knocks on their door: “Hey, we need your data on XYZ so we can check their terrorism connections!” As we know by now, NSA does these things and it happens to random people as well, despite not having any ties to terrorism. LastPass data on the server is worthless on its own, but NSA might be able to pressure the company into sending a breach notification to this user. It’s not hard to choose a message in such a way that the user will be compelled to click the link, e.g. “IMPORTANT: Your Google account might be compromised. Click to learn more.” Once they click it’s all over, my proof-of-concept successfully downloaded all the data and decrypted it with the key provided. The page can present the user with an “All good, we checked it and your account isn’t affected” message while the NSA walks away with the data.

The other scenario is of course a rogue company employee doing the same on their own. Here LastPass claims that there are internal processes to prevent employees from abusing their power in such a way. It’s striking however how their response mentions “a single person within development” — does it include server administrators or do we have to trust those? And what about two rogue employees? In the end, we have to take their word on their ability to prevent an inside job.

The fix

I reported this issue via Bugcrowd on November 22, 2018. As of LastPass 4.25.0.4 (released on February 28, 2019) this issue is considered resolved. The way I read the change, the LastPass server is still able to send users breach notifications with text and image that it can choose freely. Clicking the button (button text determined by the server) will still give the server access to all your data. Now there is additional text however saying: “LastPass has detected that you have used the password for this login on other sites, too. We recommend going to your account settings for this site, and creating a new password. Use LastPass to generate a unique, strong password for this account. You can then save the changes on the site, and to LastPass.” Ok, I guess this limits the options for social engineering slightly…

No changes to any of the other actions which will provide the server with the key to decrypt your data:

- Opening Account Settings, Security Challenge, History, Bookmarklets, Credit Monitoring

- Linking to a personal account

- Adding an identity

- Importing data if the binary component isn’t installed

- Printing all sites

Some of these actions will prompt you to re-enter your master password. That’s merely security theater however, you can check that they have g_local_key global variable set already which is all they need to decrypt your data.

One more comment on the import functionality: supposedly, a binary component is required to read a file. If the binary component isn’t installed, LastPass will fall back to uploading your file to the server. The developers apparently missed that the API to make this work locally has been part of any browser released since 2012 (yes, that’s seven years ago).

Conclusion

I wrote the original version of this Stack Exchange answer in September 2016. Back then it already pointed out that mixing trusted extension user interface with web applications is a dangerous design choice. It makes it hard to secure the communication channels, something that LastPass has been struggling with a lot. But beyond that, there is also lots of implicit trust in the server’s integrity here. While LastPass developers might be inclined to trust their servers, users have no reason for that. The keys to all their online identities are data that’s too sensitive to entrust any company with it.

LastPass has always been stressing that they cannot access your passwords, so keeping them on their servers is safe. This statement has been proven wrong several times already, and the improvements so far aren’t substantial enough to make it right. LastPass design offers too many loopholes which could be exploited by a malicious server. So far they didn’t make a serious effort to make the extension’s user interface self-contained, meaning that they keep asking you to trust their web server whenever you use LastPass.

|

|

Ian Bicking: Open Source Doesn’t Make Money Because It Isn’t Designed To Make Money |

Or: The Best Way To Do Something Is To At Least Try

We all know the story: you can’t make money on open source. Is it really true?

I’m thinking about this now because Mozilla would like to diversify its revenue in the next few years, and one constraint we have is that everything we do is open source.

There are dozens (hundreds?) of successful open source projects that have tried to become even just modest commercial enterprises, some very seriously. Results aren’t great.

I myself am trying to pitch a commercial endeavor in Mozilla right now (if writing up plans and sending them into the ether can qualify as “pitching”), and this question often comes up in feedback: can we sell something that is open source?

I have no evidence that we can (or can’t), but I will make this assertion: it’s hard to sell something that wasn’t designed to be sold.

We treat open source like it’s a poison pill for a commercial product. And yes, with an open source license it’s harder to force someone to pay for a product, though many successful businesses exist without forcing anyone.

I see an implicit assumption that makes it harder to think about this: the idea that if something is useful, it should be profitable. It’s an unspoken and morally-infused expectation, a kind of Just World hypothesis: if something has utility, if it helps people, if it’s something the world needs, if it empowers other people, then there should be a revenue opportunity. It should be possible for the thing to be your day job, to make money, to see some remuneration for your successful effort in creating or doing this thing.

That’s what we think the world should be like, but we all know it isn’t. You can’t make a living making music. Or art. You can’t even make a living taking care of children. I think this underlies many of this moment’s critiques of capitalism: there’s too many things that are important, even needed, or that fulfill us more than any profitable item, and yet are economically unsustainable.

I won’t try to fix that in this blog post, only note: not all good things make money.

But we know there is money in software. Lots of money! Is the money in secrets? If OpenSSL was secret, could it make money? If it had a licensing paywall, could it make money? Seems unlikely. The license isn’t holding it back. It’s just not shaped like something that makes money. Solving important problems isn’t enough.

So what can you get paid to do?

- People will pay a little for apps; not a lot, but a bit. Scaling up requires marketing and capital, which open source projects almost never have (and I doubt many open source projects would know what to do with capital if they had it).

- There’s always money in ads. Sadly. This could potentially offend someone enough to actually repackage your open source software with ads removed. As a form of price discrimination (e.g., paid ad removal) I think you could avoid defection.

- Fully-hosted services: Automattic’s wordpress.com is a good example here. Is Ghost doing OK? These are complete solutions: you don’t just get software, you get a website.

- People will pay if you ensure they get a personalized solution. I.e., consulting. Applied to software you get consultingware. While often maligned, many real businesses are built on this. I think Drupal is in this category.

- People will pay you for your dedicated and ongoing attention. In other words: a day job as an employee. It feels unfair to put this option on the list, but it’s such a natural progression from consultingware, and such a dominant pattern in open source that I think it deserves acknowledgement.

- Anything paired with a physical device. People will judge the value based on the hardware and software experience together.

- I’m not sure if Firefox makes money (indirectly) from ads, or as compensation for maintaining monopoly positions.

I’m sure I’m missing some interesting ideas from that list.

But if you have a business concept, and you think it might work, what does open source even have to do with it? Don’t we learn: focus on your business! On your customer! Software licensing seems like a distraction, even software is a questionable thing to focus on, separate from the business. Maybe this is why you can’t make money with open source: it’s a distraction. The question isn’t open-source-vs-proprietary, but open-source-vs-business-focused.

Another lens might be: who are you selling to? Classical scratch-your-own-itch open source software is built by programmers for programmers. And it is wildly successful, but it’s selling to people who aren’t willing to pay. They want to take the software and turn it around into greater personal productivity (which turns out to be a smart move, given the rise in programmer wages). Can we sell open source to other people? Can anyone else do anything with source code?

And so I remain pessimistic that open source can find commercial success. But also frustrated: so much software is open source except any commercial product. This is where the Free Software mission has faltered despite so many successes: software that people actually touch isn’t free or open. That’s a shame.

You may also wish to read Hacker News Comments on this post.

http://www.ianbicking.org/blog/2019/03/open-source-doesnt-make-money-by-design.html

|

|

The Servo Blog: This Week In Servo 127 |

In the past week, we merged 50 PRs in the Servo organization’s repositories.

Planning and Status

Our roadmap is available online. Plans for 2019 will be published soon.

This week’s status updates are here.

Screenshots

A standalone demo of Pathfinder running on a Magic Leap device.

Exciting works in progress

- asajeffrey is building a Magic Leap demo of the Pathfinder project.

- peterjoel is replacing the preferences hashtable with a data structure generated at build time.

- ferjm is implementing parts of the Shadow DOM API in order to support UI for media controls and complex form controls.

Notable Additions

- waywardmonkeys updated harfbuzz to version 2.3.1.

- gterzian fixed an underflow error in the HTTP cache.

- waywardmonkeys improved the safety of the harfbuzz bindings.

- Manishearth removed a bunch of unnecessary duplication that occurred during XMLHttpRequest.

- georgeroman implemented a missing WebDriver API.

- jdm made ANGLE build a DLL on Windows.

- gterzian prevented tasks from running in non-active documents.

New Contributors

- Aron Zwaan

- Caio

- violet

Interested in helping build a web browser? Take a look at our curated list of issues that are good for new contributors!

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: TenFourFox FPR13 available |

I have three main updates in mind for TenFourFox FPR14: expanding FPR13's new AppleScript support to allow injecting JavaScript into pages (so that you can drive a web page by manipulating the DOM elements within it instead of having to rely on screen coordinates and sending UI events), adding Olga's ffmpeg framework to enable H.264 video support with a sidecar library (see the previous post for details on the scheme), and a possible solution to allow JavaScript async functions which actually might fix quite a number of presently non-working sites. I'm hopeful that combined with another parser hack this will be enough to restore Github functionality on TenFourFox, but no promises. Unfortunately, it doesn't address the infamous this is undefined problem that continues to plague a number of sites and I still have no good solution for that. These projects are decent-sized undertakings, so it's possible one or two might get pushed to FPR15. FPR14 is scheduled for May 14 with Firefox 67.

Meanwhile, I took a close look at the upcoming Raptor Blackbird at the So Cal Linux Expo 17. If the full big Talos II I'm typing this on is still more green than you can dream, the smaller Blackbird may be just your size to get a good-performing 64-bit Power system free of the lurking horrors in modern PCs at a better price. Check out some detailed board pics of the prototype and other shots of the expo on Talospace. If you're still not ready to jump, I'll be reviewing mine when it arrives hopefully later this spring.

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2019/03/tenfourfox-fpr13-available.html

|

|

Mozilla Open Policy & Advocacy Blog: Mozilla statement on the Christchurch terror attack |

Like millions of people around the world, the Mozilla team has been deeply saddened by the news of the terrorist attack against the Muslim community in Christchurch, New Zealand.

The news of dozens of people killed and injured while praying in their place of worship is truly upsetting and absolutely abhorrent.

This is a call to all of us to look carefully at how hate spreads and is propagated and stand against it.

The post Mozilla statement on the Christchurch terror attack appeared first on Open Policy & Advocacy.

https://blog.mozilla.org/netpolicy/2019/03/15/mozilla-statement-on-the-christchurch-terror-attack/

|

|

Mark Surman: VP search update — and Europe |

A year ago, Mozilla Foundation started a search for a VP, Leadership Programs. The upshot of the job: work with people from around the world to build a movement to ensure our digital world stays open, healthy and humane. Over a year later, we’re in the second round of this search — finding the person to drive this work isn’t easy. However, we’re getting closer, so it’s time for an update.

At a nuts and bolts level, the person in this role will support teams at Mozilla that drive our thought leadership, fellowships and events programs. This is a great deal of work, but fairly straightforward. The tricky part is helping all the people we touch through these programs connect up with each other and work like a movement — driving to real outcomes that make digital life better.

While the position is global in scope, it will be based in Europe. This is in part because we want to work more globally, which means shifting our attention out of North America and towards African, European, Middle Eastern and South Asian time zones. Increasingly, it is also because we want to put a significant focus on Europe itself.

Europe is one of the places where a vision of an internet that balances public and private interests, and that respects people’s rights, has real traction. This vision spans everything from protecting our data to keeping digital markets open to competition to building a future where we use AI responsibly and ethically. If we want the internet to get better globally then learning from, and being more engaged with, Europe and Europeans has to be a central part of the plan.

The profile for this position is quite unique. We’re looking for someone who can think strategically and represent Mozilla publically, while also leading a distributed team within the organization; has a deep feel for both the political and technical aspects of digital life; and shares the values outlined in the Mozilla Manifesto. We’re also looking for someone who will add diversity to our senior leadership team.

In terms of an update: we retained the recruiting firm Perrett Laver in January to lead the current round of the search. We recently met with the recruiters to talk over 50 prospective candidates. There are some great people in there — people coming from the worlds of internet governance, open content, tech policy and the digital side of international development. We’re starting interviews with a handful of these people over the coming weeks — and still keeping our ear to the ground for a few more exceptional candidates as we do.

Getting this position filled soon is critical. We’re at a moment in history where the world really needs more people rolling up their sleeves to create a better digital world — this position is about gathering and supporting these people. The good news: I’m starting to feel optimistic that we can get this position filled by the middle of 2019.

PS. If you want to learn more about this role, here is the full recruiting package.

The post VP search update — and Europe appeared first on Mark Surman.

https://marksurman.commons.ca/2019/03/15/vp-search-update-and-europe/

|

|

Dave Townsend: Bridging an internal LAN to a server’s Docker containers over a VPN |

I recently decided that the basic web hosting I was using wasn’t quite a configurable or powerful as I would like so I have started paying for a VPS and am slowly moving all my sites over to it. One of the things I decided was that I wanted the majority of services it ran to be running under Docker. Docker has its pros and cons but the thing I like about it is that I can define what services run, how they run and where they store all their data in a single place, separate from the rest of the server. So now I have a /srv/docker directory which contains everything I need to backup to ensure I can reinstall all the services easily, mostly regardless of the rest of the server.

As I was adding services I quickly realised I had a problem to solve. Some of the services were obviously external facing, nginx for example. But a lot should not be exposed to the public internet but needed to still be accessible, web management interfaces etc. So I wanted to figure out how to easily access them remotely.

I considered just setting up port forwarding or a socks proxy over ssh. But this would mean having to connect to ssh whenever needed and either defining all the ports and docker IPs (which I would then have to make static) in the ssh config or having to switch proxies in my browser whenever I needed to access a service and also would only really support web protocols.

Exposing them publicly anyway but requiring passwords was another option, I wasn’t a big fan of this either though. It would require configuring an nginx reverse proxy or something everytime I added a new service and I thought I could come up with something better.

At first I figured a VPN was going to be overkill, but eventually I decided that once set up it would give me the best experience. I also realised I could then set up a persistent VPN from my home network to the VPS so when at home, or when connected to my home network over VPN (already set up) I would have access to the containers without needing to do anything else.

Alright, so I have a home router that handles two networks, the LAN and its own VPN clients. Then I have a VPS with a few docker networks running on it. I want them all to be able to access each other and as a bonus I want to be able to just use names to connect to the docker containers, I don’t want to have to remember static IP addresses. This is essentially just using a VPN to bridge the networks, which is covered in many other places, except I had to visit so many places to put all the pieces together that I thought I’d explain it in my own words, if only so I have a single place to read when I need to do this again.

In my case the networks behind my router are 10.10.* for the local LAN and 10.11.* for its VPN clients. On the VPS I configured my docker networks to be under 10.12.*.

0. Configure IP forwarding.

The zeroth step is to make sure that IP forwarding is enabled and not firewalled any more than it needs to be on both router and VPS. How you do that will vary and it’s likely that the router will already have it enabled. At the least you need to use sysctl to set net.ipv4.ip_forward=1 and probably tinker with your firewall rules.

1. Set up a basic VPN connection.

First you need to set up a simple VPN connection between the router and the VPS. I ended up making the VPS the server since I can then connect directly to it from another machine either for testing or if my home network is down. I don’t think it really matters which is the “server” side of the VPN, either should work, you’ll just have to invert some of the description here if you choose the opposite.

There are many many tutorials on doing this so I’m not going to talk about it much. Just one thing to say is that you must be using certificate authentication (most tutorials cover setting this up), so the VPS can identify the router by its common name. Don’t add any “route” configuration yet. You could use redirect-gateway in the router config to make some of this easier, but that would then mean that all your internet traffic (from everything on the home LAN) goes through the VPN which I didn’t want. I set the VPN addresses to be in 10.12.10.* (this subnet is not used by any of the docker networks).

Once you’re done here the router and the VPS should be able to ping their IP addresses on the VPN tunnel. The VPS IP is 10.12.10.1, the router’s gets assigned on connection. They won’t be able to reach beyond that yet though.

2. Make the docker containers visible to the router.

Right now the router isn’t able to send packets to the docker containers because it doesn’t know how to get them there. It knows that anything for 10.12.10.* goes through the tunnel, but has no idea that other subnets are beyond that. This is pretty trivial to fix. Add this to the VPS’s VPN configuration:

push "route 10.12.0.0 255.255.0.0"

When the router connects to the VPS the VPN server will tell it that this route can be accessed through this connection. You should now be able to ping anything in that network range from the router. But neither the VPS nor the docker containers will be able to reach the internal LANs. In fact if you try to ping a docker container’s IP from the local LAN the ping packet should reach it, but the container won’t know how to return it!

3. Make the local LAN visible to the VPS.

Took me a while to figure this out. Not quite sure why, but you can’t just add something similar to a VPN’s client configuration. Instead the server side has to know in advance what networks a client is going to give access to. So again you’re going to be modifying the VPS’s VPN configuration. First the simple part. Add this to the configuration file:

route 10.10.0.0 255.255.0.0 route 10.11.0.0 255.255.0.0

This makes openVPN modify the VPS’s routing table telling it it can direct all traffic to those networks to the VPN interface. This isn’t enough though. The VPN service will receive that traffic but not know where to send it on to. There could be many clients connected, which one has those networks? You have to add some client specific configuration. Create a directory somewhere and add this to the configuration file:

client-config-dir /absolute/path/to/directory

Do NOT be tempted to use a relative path here. It took me more time than I’d like to admit to figure out that when running as a daemon the open vpn service won’t be able to find it if it is a relative path. Now, create a file in the directory, the filename must be exactly the common name of the router’s VPN certificate. Inside it put this:

iroute 10.10.0.0 255.255.0.0 iroute 10.11.0.0 255.255.0.0

This tells the VPN server that this is the client that can handle traffic to those networks. So now everything should be able to ping everything else by IP address. That would be enough if I didn’t also want to be able to use hostnames instead of IP addresses.

4. Setting up DNS lookups.

Getting this bit to work depends on what DNS server the router is running. In my case (and many cases) this was dnsmasq which makes this fairly straightforward. The first step is setting up a DNS server that will return results for queries for the running docker containers. I found the useful dns-proxy-server. It runs as the default DNS server on the VPS, for lookups it looks for docker containers with a matching hostname and if not forwards the request on to an upstream DNS server. The VPS can now find the a docker container’s IP address by name.

For the router (and so anything on the local LAN) to be able to look them up it needs to be able to query the DNS server on the VPS. This meant giving the DNS container a static IP address (the only one this entire setup needs!) and making all the docker hostnames share a domain suffix. Then add this line to the router’s dnsmasq.conf:

server=/

This tells dnsmasq that anytime it receives a query for *.domain it passes on the request to the VPS’s DNS container.

5. Done!

Everything should be set up now. Enjoy your direct access to your docker containers. Sorry this got long but hopefully it will be useful to others in the future.

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Thank you, Denelle Dixon |

I want to take this opportunity to thank Denelle Dixon for her partnership, leadership and significant contributions to Mozilla over the last six years.

Denelle joined Mozilla Corporation in September 2012 as an Associate General Counsel and rose through the ranks to lead our global business and operations as our Chief Operating Officer. Next month, after an incredible tour of duty at Mozilla, she will step down as a full-time Mozillian to join the Stellar Development Foundation as their Executive Director and CEO.

As a key part of our senior leadership team, Denelle helped to build a stronger more resilient Mozilla, including leading the acquisition of Pocket, orchestrating our major partnerships, and helping refocus us to unlock the growth opportunities ahead. Denelle has had a huge impact here — on our strategy, execution, technology, partners, brand, culture, people, the list goes on. Although I will miss her partnership deeply, I will be cheering her on in her new role as she embarks on the next chapter of her career.

As we conduct a search for our next COO, I will be working more closely with our business and operations leaders and teams as we execute on our strategy that will give people more control over their connected lives and help build an Internet that’s healthier for everyone.

Thank you, Denelle for everything, and all the best on your next adventure!

The post Thank you, Denelle Dixon appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2019/03/14/thank-you-denelle-dixon/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Fast, Bump-Allocated Virtual DOMs with Rust and Wasm |

Dodrio is a virtual DOM library written in Rust and WebAssembly. It takes advantage of both Wasm’s linear memory and Rust’s low-level control by designing virtual DOM rendering around bump allocation. Preliminary benchmark results suggest it has best-in-class performance.

- Background

- Dodrio from a User’s Perspective

- Internal Design

- Preliminary Benchmarks

- Future Work

- Conclusion

Background

Virtual DOM Libraries

Virtual DOM libraries provide a declarative interface to the Web’s imperative DOM. Users describe the desired DOM state by generating a virtual DOM tree structure, and the library is responsible for making the Web page’s physical DOM reflect the user-generated virtual DOM tree. Libraries employ some diffing algorithm to decrease the number of expensive DOM mutation methods they invoke. Additionally, they tend to have facilities for caching to further avoid unnecessarily re-rendering components which have not changed and re-diffing identical subtrees.

Bump Allocation

Bump allocation is a fast, but limited approach to memory allocation. The allocator maintains a chunk of memory, and a pointer pointing within that chunk. To allocate an object, the allocator rounds the pointer up to the object’s alignment, adds the object’s size, and does a quick test that the pointer didn’t overflow and still points within the memory chunk. Allocation is only a small handful of instructions. Likewise, deallocating every object at once is fast: reset the pointer back to the start of the chunk.

The disadvantage of bump allocation is that there is no general way to deallocate individual objects and reclaim their memory regions while other objects are still in use.

These trade offs make bump allocation well-suited for phase-oriented allocations. That is, a group of objects that will all be allocated during the same program phase, used together, and finally deallocated together.

bump_allocate(size, align):

aligned_pointer = round_up_to(self.pointer, align)

new_pointer = aligned_pointer + size

if no overflow and new_pointer < self.end_of_chunk:

self.pointer = new_pointer

return aligned_pointer

else:

handle_allocation_failure()

Dodrio from a User’s Perspective

First off, we should be clear about what Dodrio is and is not. Dodrio is only a virtual DOM library. It is not a full framework. It does not provide state management, such as Redux stores and actions or two-way binding. It is not a complete solution for everything you encounter when building Web applications.

Using Dodrio should feel fairly familiar to anyone who has used Rust or virtual DOM libraries before. To define how a struct is rendered as HTML, users implement the dodrio::Render trait, which takes an immutable reference to self and returns a virtual DOM tree.

Dodrio uses the builder pattern to create virtual DOM nodes. We intend to support optional JSX-style, inline HTML templating syntax with compile-time procedural macros, but we’ve left it as future work.

The 'a and 'bump lifetimes in the dodrio::Render trait’s interface and the where 'a: 'bump clause enforce that the self reference outlives the bump allocation arena and the returned virtual DOM tree. This means that if self contains a string, for example, the returned virtual DOM can safely use that string by reference rather than copying it into the bump allocation arena. Rust’s lifetimes and borrowing enable us to be aggressive with cost-saving optimizations while simultaneously statically guaranteeing their safety.

struct Hello {

who: String,

}

impl Render for Hello {

fn render<'a, 'bump>(&'a self, bump: &'bump Bump) -> Node<'bump>

where

'a: 'bump,

{

span(bump)

.children([text("Hello, "), text(&self.who), text("!")])

.finish()

}

}

Event handlers are given references to the root dodrio::Render component, a handle to the virtual DOM instance that can be used to schedule re-renders, and the DOM event itself.

struct Counter {

count: u32,

}

impl Render for Counter {

fn render<'a, 'bump>(&'a self, bump: &'bump Bump) -> Node<'bump>

where

'a: 'bump,

{

let count = bumpalo::format!(in bump, "{}", self.count);

div(bump)

.children([

text(count.into_bump_str()),

button(bump)

.on("click", |root, vdom, _event| {

let counter = root.unwrap_mut::();

counter.count += 1;

vdom.schedule_render();

})

.children([text("+")])

.finish(),

])

.finish()

}

}

Additionally, Dodrio also has a proof-of-concept API for defining rendering components in JavaScript. This reflects the Rust and Wasm ecosystem’s strong integration story for JavaScript, that enables both incremental porting to Rust and heterogeneous, polyglot applications where just the most performance-sensitive code paths are written in Rust.

class Greeting {

constructor(who) {

this.who = who;

}

render() {

return {

tagName: "p",

attributes: [{ name: "class", value: "greeting" }],

listeners: [{ on: "click", callback: this.onClick.bind(this) }],

children: [

"Hello, ",

{

tagName: "strong",

children: [this.who],

},

],

};

}

async onClick(vdom, event) {

// Be more excited!

this.who += "!";

// Schedule a re-render.

await vdom.render();

console.log("re-rendering finished!");

}

}

#[wasm_bindgen]

extern "C" {

// Import the JS `Greeting` class.

#[wasm_bindgen(extends = Object)]

type Greeting;

// And the `Greeting` class's constructor.

#[wasm_bindgen(constructor)]

fn new(who: &str) -> Greeting;

}

// Construct a JS rendering component from a `Greeting` instance.

let js = JsRender::new(Greeting::new("World"));

Finally, Dodrio exposes a safe public interface, and we have never felt the need to reach for unsafe when authoring Dodrio rendering components.

Internal Design

Both virtual DOM tree rendering and diffing in Dodrio leverage bump allocation. Rendering constructs bump-allocated virtual DOM trees from component state. Diffing batches DOM mutations into a bump-allocated “change list” which is applied to the physical DOM all at once after diffing completes. This design aims to maximize allocation throughput, which is often a performance bottleneck for virtual DOM libraries, and minimize bouncing back and forth between Wasm, JavaScript, and native DOM functions, which should improve temporal cache locality and avoid out-of-line calls.

Rendering Into Double-Buffered Bump Allocation Arenas

Virtual DOM rendering exhibits phases that we can exploit with bump allocation:

- A virtual DOM tree is constructed by a

Renderimplementation, - it is diffed against the old virtual DOM tree,

- saved until the next time we render a new virtual DOM tree,

- when it is diffed against that new virtual DOM tree,

- and then finally it and all of its nodes are destroyed.

This process repeats ad infinitum.

------------------- Time ------------------->

Tree 0: [ render | ------ | diff ]

Tree 1: [ render | diff | ------ | diff ]

Tree 2: [ render | diff | ------ | diff ]

Tree 3: [ render | diff | ------ | diff ]

...

At any given moment in time, only two virtual DOM trees are alive. Therefore, we can double buffer two bump allocation arenas that switch back and forth between the roles of containing the new or the old virtual DOM tree:

- A virtual DOM tree is rendered into bump arena A,

- the new virtual DOM tree in bump arena A is diffed with the old virtual DOM tree in bump arena B,

- bump arena B has its bump pointer reset,

- bump arenas A and B are swapped.

------------------- Time ------------------->

Arena A: [ render | ------ | diff | reset | render | diff | -------------- | diff | reset | render | diff ...

Arena B: [ render | diff | -------------- | diff | reset | render | diff | -------------- | diff ...

Diffing and Change Lists

Dodrio uses a na"ive, single-pass algorithm to diff virtual DOM trees. It walks both the old and new trees in unison and builds up a change list of DOM mutation operations whenever an attribute, listener, or child differs between the old and the new tree. It does not currently use any sophisticated algorithms to minimize the number of operations in the change list, such as longest common subsequence or patience diffing.

The change lists are constructed during diffing, applied to the physical DOM, and then destroyed. The next time we render a new virtual DOM tree, the process is repeated. Since at most one change list is alive at any moment, we use a single bump allocation arena for all change lists.

A change list’s DOM mutation operations are encoded as instructions for a custom stack machine. While an instruction’s discriminant is always a 32-bit integer, instructions are variably sized as some have immediates while others don’t. The machine’s stack contains physical DOM nodes (both text nodes and elements), and immediates encode pointers and lengths of UTF-8 strings.

The instructions are emitted on the Rust and Wasm side, and then batch interpreted and applied to the physical DOM in JavaScript. Each JavaScript function that interprets a particular instruction takes four arguments:

- A reference to the JavaScript

ChangeListclass that represents the stack machine, - a

Uint8Arrayview of Wasm memory to decode strings from, - a

Uint32Arrayview of Wasm memory to decode immediates from, - and an offset

iwhere the instruction’s immediates (if any) are located.

It returns the new offset in the 32-bit view of Wasm memory where the next instruction is encoded.

There are instructions for:

- Creating, removing, and replacing elements and text nodes,

- adding, removing, and updating attributes and event listeners,

- and traversing the DOM.

For example, the AppendChild instruction has no immediates, but expects two nodes to be on the top of the stack. It pops the first node from the stack, and then calls Node.prototype.appendChild with the popped node as the child and the node that is now at top of the stack as the parent.

AppendChild instruction// Allocate an instruction with zero immediates.

fn op0(&self, discriminant: ChangeDiscriminant) {

self.bump.alloc(discriminant as u32);

}

/// Immediates: `()`

///

/// Stack: `[... Node Node] -> [... Node]`

pub fn emit_append_child(&self) {

self.op0(ChangeDiscriminant::AppendChild);

}

AppendChild instructionfunction appendChild(changeList, mem8, mem32, i) {

const child = changeList.stack.pop();

top(changeList.stack).appendChild(child);

return i;

}

On the other hand, the SetText instruction expects a text node on top of the stack, and does not modify the stack. It has a string encoded as pointer and length immediates. It decodes the string, and calls the Node.prototype.textContent setter function to update the text node’s text content with the decoded string.

SetText instruction// Allocate an instruction with two immediates.

fn op2(&self, discriminant: ChangeDiscriminant, a: u32, b: u32) {

self.bump.alloc([discriminant as u32, a, b]);

}

/// Immediates: `(pointer, length)`

///

/// Stack: `[... TextNode] -> [... TextNode]`

pub fn emit_set_text(&self, text: &str) {

self.op2(

ChangeDiscriminant::SetText,

text.as_ptr() as u32,

text.len() as u32,

);

}

SetText instructionfunction setText(changeList, mem8, mem32, i) {

const pointer = mem32[i++];

const length = mem32[i++];

const str = string(mem8, pointer, length);

top(changeList.stack).textContent = str;

return i;

}

Preliminary Benchmarks

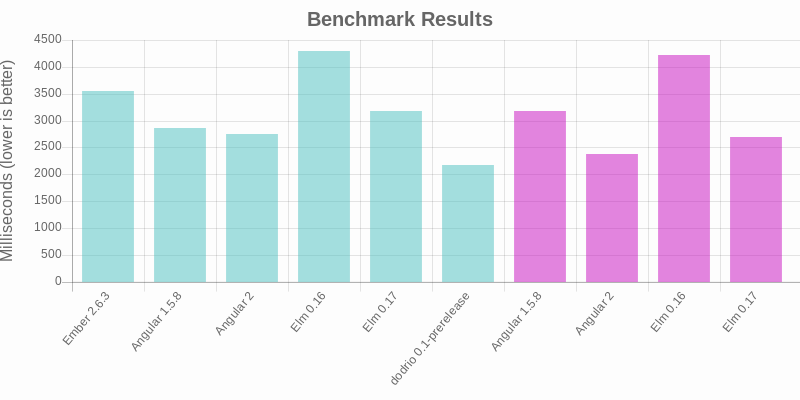

To get a sense of Dodrio’s speed relative to other libraries, we added it to Elm’s Blazing Fast HTML benchmark that compares rendering speeds of TodoMVC implementations with different libraries. They claim that the methodology is fair and that the benchmark results should generalize. They also subjectively measure how easy it is to optimize the implementations to improve performance (for example, by adding well-placed shouldComponentUpdate hints in React and lazy wrappers in Elm). We followed their same methodology and disabled Dodrio’s on-by-default, once-per-animation-frame render debouncing, giving it the same handicap that the Elm implementation has.

That said, there are some caveats to these benchmark results. The React implementation had bugs that prevented it from completing the benchmark, so we don’t include its measurements below. If you are curious, you can look at the original Elm benchmark results to see how it generally fared relative to some of the other libraries measured here. Second, we made an initial attempt to update the benchmark to the latest version of each library, but quickly got in over our heads, and therefore this benchmark is not using the latest release of each library.

With that out of the way let’s look at the benchmark results. We ran the benchmarks in Firefox 67 on Linux. Lower is better, and means faster rendering times.

| Library | Optimized? | Milliseconds |

|---|---|---|

| Ember 2.6.3 | No | 3542 |

| Angular 1.5.8 | No | 2856 |

| Angular 2 | No | 2743 |

| Elm 0.16 | No | 4295 |

| Elm 0.17 | No | 3170 |

| Dodrio 0.1-prerelease | No | 2181 |

| Angular 1.5.8 | Yes | 3175 |

| Angular 2 | Yes | 2371 |

| Elm 0.16 | Yes | 4229 |

| Elm 0.17 | Yes | 2696 |

Dodrio is the fastest library measured in the benchmark. This is not to say that Dodrio will always be the fastest in every scenario — that is undoubtedly false. But these results validate Dodrio’s design and show that it already has best-in-class performance. Furthermore, there is room to make it even faster:

- Dodrio is brand new, and has not yet had the years of work poured into it that other libraries measured have. We have not done any serious profiling or optimization work on Dodrio yet!

-

The Dodrio TodoMVC implementation used in the benchmark does not use

shouldComponentUpdate-style optimizations, like other implementations do. These techniques are still available to Dodrio users, but you should need to reach for them much less frequently because idiomatic implementations are already fast.

Future Work

So far, we haven’t invested in polishing Dodrio’s ergonomics. We would like to explore adding type-safe HTML templates that boil down to Dodrio virtual DOM tree builder invocations.

Additionally, there are a few more ways we can potentially improve Dodrio’s performance:

- We can create new instructions for common DOM mutation operations. For example, we can avoid decoding attribute name strings from immediates if we have instructions for the setting the most common attributes directly (e.g.

"id","class", etc…) -

We can investigate smarter diffing algorithms. Initial profiling shows that Dodrio spends much more time applying diffs than generating diffs or constructing virtual DOM trees. It is possible that improving the diffing algorithm could emit smaller diffs that are faster to apply.

-

Dodrio’s caching mechanisms (similar to React’s

shouldComponentUpdate) currently avoid reconstructing virtual DOM subtrees, but do not yet avoid re-diffing them. Extending the caching mechanisms to also avoid re-diffing them should be relatively straight forward and yield speed ups when caching is used.

For both ergonomics and further performance improvements, we would like to start gathering feedback informed by real world usage before investing too much more effort.

Evan Czaplicki pointed us to a second benchmark — krausest/js-framework-benchmark — that we can use to further evaluate Dodrio’s performance. We look forward to implementing this benchmark for Dodrio and gathering more test cases and insights into performance.

Further in the future, the WebAssembly host bindings proposal will enable us to interpret the change list’s operations in Rust and Wasm without trampolining through JavaScript to invoke DOM methods.

Conclusion

Dodrio is a new virtual DOM library that is designed to leverage the strengths of both Wasm’s linear memory and Rust’s low-level control by making extensive use of fast bump allocation. If you would like to learn more about Dodrio, we encourage you to check out its repository and examples!

Thanks to Luke Wagner and Alex Crichton for their contributions to Dodrio’s design, and participation in brainstorming and rubber ducking sessions. We also discussed many of these ideas with core developers on the React, Elm, and Ember teams, and we thank them for the context and understanding these discussions ultimately brought to Dodrio’s design. A final round of thanks to Jason Orendorff, Lin Clark, Till Schneidereit, Alex Crichton, Luke Wagner, Evan Czaplicki, and Robin Heggelund Hansen for providing valuable feedback on early drafts of this document.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/03/fast-bump-allocated-virtual-doms-with-rust-and-wasm/

|

|

Mozilla Reps Community: Rep of the Month – February 2019 |

Please join us in congratulating Edoardo Viola, our Rep of the Month for February 2019!

Edoardo is a long-time Mozillian from Italy and has been a Rep for almost two years. He’s a Resource Rep and has been on the Reps Council until January. When he’s not busy with Reps work, Edoardo is a Mentor in the Open Leadership Training Program. In the past he has contributed to Campus Clubs as well as MozFest, where he was a Space Wrangler for the Web Literacy Track.

Recently Edoardo helped out at FOSDEM in Brussels as part of the Mozilla volunteers organizing our presence. He helped out at the booth, as well as helping to moderate the Mozilla Dev Room. He also contributes to the Internet Health Report as part of the volunteer team to give input for the next edition of the report.

To congratulate him, please head over to Discourse!

https://blog.mozilla.org/mozillareps/2019/03/14/rep-of-the-month-february-2019/

|

|

Eric Rahm: Doubling the Number of Content Processes in Firefox |

Over the past year, the Fission MemShrink project has been working tirelessly to reduce the memory overhead of Firefox. The goal is to allow us to start spinning up more processes while still maintaining a reasonable memory footprint. I’m happy to announce that we’ve seen the fruits of this labor: as of version 66 we’re doubling the default number of content processes from 4 to 8.

Doubling the number of content processes is the logical extension of the e10s-multi project. Back when that project wrapped up we chose to limit the default number of processes to 4 in order to balance the benefits of multiple content processes — fewer crashes, better site isolation, improved performance when loading multiple pages — with the impact on memory usage for our users.

Our telemetry has looked really good: if we compare beta 59 (roughly when this project started) with beta 66, where we decided to let the increase be shipped to our regular users, we see a virtually unchanged total memory usage for our 25th, median, and 75th percentile and a modest 9% increase for the 95th percentile on Windows 64-bit.

Doubling the number of content processes and not seeing a huge jump is quite impressive. Even on our worst-case-scenario stress test — AWSY which loads 100 pages in 30 tabs, repeated 3 times — we only saw a 6% increase in memory usage when turning on 8 content processes when compared to when we started the project.

This is a huge accomplishment and I’m very proud of the loose-knit team of contributors who have done some phenomenal feats to get us to this point. There have been some big wins, but really it’s the myriad of minor improvements that compounded into a large impact. This has ranged from delay-loading browser JavaScript code until it’s needed (or not at all), to low-level changes to packing C++ data structures more efficiently, to large system-wide changes to how we generate bindings that glue together our JavaScript and C++ code. You can read more about the background of this project and many of the changes in our initial newsletter and the follow-up.

While I’m pleased with where we are now, we still have a way to go to get our overhead down even further. Fear not, for we have a quite a few changes in the pipeline including a fork server to help further reduce memory usage on Linux and macOS, work to share font data between processes, and work to share more CSS data between processes. In addition to reducing overhead we now have a tab unloading feature in Nightly 67 that will proactively unload tabs when it looks like you’re about to run out of memory. So far the results in reducing the number of out-of-memory crashes are looking really good and we’re hoping to get that released to a wider audience in the near future.

http://www.erahm.org/2019/03/13/doubling-the-number-of-content-processes-in-firefox/

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Get better password management with Firefox Lockbox on iPad |

We access the web on all sorts of devices from our laptop to our phone to our tablets. And we need our passwords everywhere to log into an account. This … Read more

The post Get better password management with Firefox Lockbox on iPad appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: Looking for the Refresh header |

The other day someone filed a bug on curl that we don’t support redirects with the Refresh header. This took me down a rabbit hole of Refresh header research and I’ve returned to share with you what I learned down there.

tl;dr Refresh is not a standard HTTP header.

As you know, an HTTP redirect is specified to use a 3xx response code and a Location: header to point out the new URL (I use the term URL here but you know what I mean). This has been the case since RFC 1945 (HTTP/1.0). According to an old mail from Roy T Fielding (dated June 1996), Refresh “didn’t make it” into that spec. That was the first “real” HTTP specification. (And the HTTP we used before 1.0 didn’t even have headers!)

The little detail that it never made it into the 1.0 spec or any later one, doesn’t seem to have affected the browsers. Still today, browsers keep supporting the Refresh header as a sort of Location: replacement even though it seems to never have been present in a HTTP spec.

In good company

curl is not the only HTTP library that doesn’t support this non-standard header. The popular python library requests apparently doesn’t according to this bug from 2017, and another bug was filed about it already back in 2011 but it was just closed as “old” in 2014.

I’ve found no support in wget or wget2 either for this header.

I didn’t do any further extensive search for other toolkits’ support, but it seems that the browsers are fairly alone in supporting this header.

How common is the the Refresh header?

I decided to make an attempt to figure out, and for this venture I used the Rapid7 data trove. The method that data is collected with may not be the best – it scans the IPv4 address range and sends a HTTP request to each TCP port 80, setting the IP address in the Host: header. The result of that scan is 52+ million HTTP responses from different and current HTTP origins. (Exactly 52254873 responses in my 59GB data dump, dated end of February 2019).

Results from my scans

- Location is used in 18.49% of the responses

- Refresh is used in 0.01738% of the responses (exactly 9080 responses featured them)

- Location is thus used 1064 times more often than Refresh

- In 35% of the cases when Refresh is used, Location is also used

- curl thus handles 99.9939% of the redirects in this test

Additional notes

- When Refresh is the only redirect header, the response code is usually 200 (with 404 being the second most)

- When both headers are used, the response code is almost always 30x

- When both are used, it is common to redirect to the same target and it is also common for the Refresh header value to only contain a number (for the number of seconds until “refresh”).

Refresh from HTML content

Redirects can also be done by meta tags in HTML and sending the refresh that way, but I have not investigated how common as that isn’t strictly speaking HTTP so it is outside of my research (and interest) here.

In use, not documented, not in the spec

Just another undocumented corner of the web.

When I posted about these findings on the HTTPbis mailing list, it was pointed out that WHATWG mentions this header in their iana page. I say mention because calling that documenting would be a stretch…

It is not at all clear exactly what the header is supposed to do and it is not documented anywhere. It’s not exactly a redirect, but almost?

Will/should curl support it?

A decision hasn’t been made about it yet. With such a very low use frequency and since we’ve managed fine without support for it so long, maybe we can just maintain the situation and instead argue that we should just completely deprecate this header use from the web?

Updates

After this post first went live, I got some further feedback and data that are relevant and interesting.

- Yoav Wiess created a patch for Chrome to count how often they see this header used in real life.

- Eric Lawrence pointed out that IE had several incompatibilities in its Refresh parser back in the day.

- Boris pointed out (in the comments below) the WHATWG documented steps for handling the header.

- The use of tag refresh in contents is fairly high. The Chrome counter says almost 4% of page loads!

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2019/03/12/looking-for-the-refresh-header/

|

|

Andrew Halberstadt: Task Configuration at Scale |

A talk I did for the Automationeer’s Assemble series on how Mozilla handles complexity in their CI configuration.

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Iodide: an experimental tool for scientific communication and exploration on the web |

In the last 10 years, there has been an explosion of interest in “scientific computing” and “data science”: that is, the application of computation to answer questions and analyze data in the natural and social sciences. To address these needs, we’ve seen a renaissance in programming languages, tools, and techniques that help scientists and researchers explore and understand data and scientific concepts, and to communicate their findings. But to date, very few tools have focused on helping scientists gain unfiltered access to the full communication potential of modern web browsers. So today we’re excited to introduce Iodide, an experimental tool meant to help scientists write beautiful interactive documents using web technologies, all within an iterative workflow that will be familiar to many scientists.

Beyond being just a programming environment for creating living documents in the browser, Iodide attempts to remove friction from communicative workflows by always bundling the editing tool with the clean readable document. This diverges from IDE-style environments that output presentational documents like .pdf files (which are then divorced from the original code) and cell-based notebooks which mix code and presentation elements. In Iodide, you can get both a document that looks however you want it to look, and easy access to the underlying code and editing environment.

Iodide is still very much in an alpha state, but following the internet aphorism “If you’re not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you’ve launched too late”, we’ve decided to do a very early soft launch in the hopes of getting feedback from a larger community. We have a demo that you can try out right now, but expect a lot of rough edges (and please don’t use this alpha release for critical work!). We’re hoping that, despite the rough edges, if you squint at this you’ll be able to see the value of the concept, and that the feedback you give us will help us figure out where to go next.

How we got to Iodide

Data science at Mozilla

At Mozilla, the vast majority of our data science work is focused on communication. Though we sometimes deploy models intended to directly improve a user’s experience, such as the recommendation engine that helps users discover browser extensions, most of the time our data scientists analyze our data in order to find and share insights that will inform the decisions of product managers, engineers and executives.

Data science work involves writing a lot of code, but unlike traditional software development, our objective is to answer questions, not to produce software. This typically results in some kind of report — a document, some plots, or perhaps an interactive data visualization. Like many data science organizations, at Mozilla we explore our data using fantastic tools like Jupyter and R-Studio. However, when it’s time to share our results, we cannot usually hand off a Jupyter notebook or an R script to a decision-maker, so we often end up doing things like copying key figures and summary statistics to a Google Doc.

We’ve found that making the round trip from exploring data in code to creating a digestible explanation and back again is not always easy. Research shows that many people share this experience. When one data scientist is reading through another’s final report and wants to look at the code behind it, there can be a lot of friction; sometimes tracking down the code is easy, sometimes not. If they want to attempt to experiment with and extend the code, things obviously get more difficult still. Another data scientist may have your code, but may not have an identical configuration on their machine, and setting that up takes time.

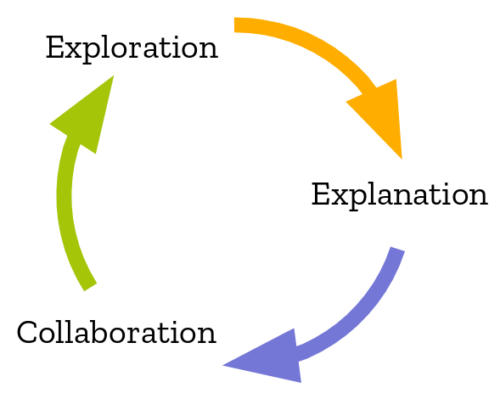

The virtuous circle of data science work.

Why is there so little web in science?

Against the background of these data science workflows at Mozilla, in late 2017 I undertook a project that called for interactive data visualization. Today you can create interactive visualizations using great libraries for Python, R, and Julia, but for what I wanted to accomplish, I needed to drop down to Javascript. This meant stepping away from my favorite data science environments. Modern web development tools are incredibly powerful, but extremely complicated. I really didn’t want to figure out how to get a fully-fledged Javascript build toolchain with hot module reloading up and running, but short of that I couldn’t find much aimed at creating clean, readable web documents within the live, iterative workflow familiar to me.

I started wondering why this tool didn’t exist — why there’s no Jupyter for building interactive web documents — and soon zoomed out to thinking about why almost no one uses Javascript for scientific computing. Three big reasons jumped out:

- Javascript itself has a mixed reputation among scientists for being slow and awkward;

- there aren’t many scientific computing libraries that run in the browser or that work with Javascript; and,

- as I’d discovered, there are very few scientific coding tools that enable fast iteration loop and also grant unfiltered access to the presentational capabilities in the browser.

These are very big challenges. But as I thought about it more, I began to think that working in a browser might have some real advantages for the kind of communicative data science that we do at Mozilla. The biggest advantage, of course, is that the browser has arguably the most advanced and well-supported set of presentation technologies on the planet, from the DOM to WebGL to Canvas to WebVR.

Thinking on the workflow friction mentioned above, another potential advantage occurred to me: in the browser, the final document need not be separate from the tool that created it. I wanted a tool designed to help scientists iterate on web documents (basically single-purpose web apps for explaining an idea)… and many tools we were using were themselves basically web apps. For the use case of writing these little web-app-documents, why not bundle the document with the tool used to write it?

By doing this, non-technical readers could see my nice looking document, but other data scientists could instantly get back to the original code. Moreover, since the compute kernel would be the browser’s JS engine, they’d be able to start extending and experimenting with the analysis code immediately. And they’d be able to do all this without connecting to remote computing resources or installing any software.

Towards Iodide

I started discussing the potential pros and cons of scientific computing in the browser with my colleagues, and in the course of our conversations, we noticed some other interesting trends.

Inside Mozilla we were seeing a lot of interesting demos showing off WebAssembly, a new way for browsers to run code written in languages other than Javascript. WebAssembly allows programs to be run at incredible speed, in some cases close to native binaries. We were seeing examples of computationally-expensive processes like entire 3D game engines running within the browser without difficulty. Going forward, it would be possible to compile best-in-class C and C++ numerical computing libraries to WebAssembly and wrap them in ergonomic JS APIs, just as the SciPy project does for Python. Indeed, projects had started to do this already.

WebAssembly makes it possible to run code at near-native speed in the browser.

We also noticed the Javascript community’s willingness to introduce new syntax when doing so helps people to solve their problem more effectively. Perhaps it would be possible to emulate some of key syntactic elements that make numerical programming more comprehensible and fluid in MATLAB, Julia, and Python — matrix multiplication, multidimensional slicing, broadcast array operations, and so on. Again, we found other people thinking along similar lines.

With these threads converging, we began to wonder if the web platform might be on the cusp of becoming a productive home for scientific computing. At the very least, it looked like it might evolve to serve some of the communicative workflows that we encounter at Mozilla (and that so many others encounter in industry and academia). With the core of Javascript improving all the time and the possibility of adding syntax extensions for numerical programming, perhaps JS itself could be made more appealing to scientists. WebAssembly seemed to offer a path to great science libraries. The third leg of the stool would be an environment for creating data science documents for the web. This last element is where we decided to focus our initial experimentation, which brought us to Iodide.

The anatomy of Iodide

Iodide is a tool designed to give scientists a familiar workflow for creating great-looking interactive documents using the full power of the web platform. To accomplish that, we give you a “report” — basically a web page that you can fill in with your content — and some tools for iteratively exploring data and modifying your report to create something you’re ready to share. Once you’re ready, you can send a link directly to your finalized report. If your colleagues and collaborators want to review your code and learn from it, they can drop back to an exploration mode in one click. If they want to experiment with the code and use it as the basis of their own work, with one more click they can fork it and start working on their own version.

Read on to learn a bit more about some of the ideas we’re experimenting with in an attempt to make this workflow feel fluid.

The Explore and Report Views

Iodide aims to tighten the loop between exploration, explanation, and collaboration. Central to that is the ability to move back and forth between a nice looking write-up and a useful environment for iterative computational exploration.

When you first create a new Iodide notebook, you start off in the “explore view.” This provides a set of panes including an editor for writing code, a console for viewing the output from code you evaluate, a workspace viewer for examining the variables you’ve created during your session, and a “report preview” pane in which you can see a preview of your report.

Editing a Markdown code chunk in Iodide’s explore view.

By clicking the “REPORT” button in the top right corner, the contents of your report preview will expand to fill the entire window, allowing you to put the story you want to tell front and center. Readers who don’t know how to code or who aren’t interested in the technical details are able to focus on what you’re trying to convey without having to wade through the code. When a reader visits the link to the report view, your code will runs automatically. if they want to review your code, simply clicking the “EXPLORE” button in the top right will bring them back into the explore view. From there, they can make a copy of the notebook for their own explorations.

Moving from explore to report view.

Whenever you share a link to an Iodide notebook, your collaborator can always access to both of these views. The clean, readable document is never separated from the underlying runnable code and the live editing environment.

Live, interactive documents with the power of the Web Platform

Iodide documents live in the browser, which means the computation engine is always available. Whenever you share your work, you share a live interactive report with running code. Moreover, since the computation happens in the browser alongside the presentation, there is no need to call a language backend in another process. This means that interactive documents update in real-time, opening up the possibility of seamless 3D visualizations, even with the low-latency and high frame-rate required for VR.

Sharing, collaboration, and reproducibility

Building Iodide in the web simplifies a number of the elements of workflow friction that we’ve encountered in other tools. Sharing is simplified because the write-up and the code are available at the same URL rather than, say, pasting a link to a script in the footnotes of a Google Doc. Collaboration is simplified because the compute kernel is the browser and libraries can be loaded via an HTTP request like any webpage loads script — no additional languages, libraries, or tools need to be installed. And because browsers provide a compatibility layer, you don’t have to worry about notebook behavior being reproducible across computers and OSes.

To support collaborative workflows, we’ve built a fairly simple server for saving and sharing notebooks. There is a public instance at iodide.io where you can experiment with Iodide and share your work publicly. It’s also possible to set up your own instance behind a firewall (and indeed this is what we’re already doing at Mozilla for some internal work). But importantly, the notebooks themselves are not deeply tied to a single instance of the Iodide server. Should the need arise, it should be easy to migrate your work to another server or export your notebook as a bundle for sharing on other services like Netlify or Github Pages (more on exporting bundles below under “What’s next?”). Keeping the computation in the client allows us to focus on building a really great environment for sharing and collaboration, without needing to build out computational resources in the cloud.

Pyodide: The Python science stack in the browser

When we started thinking about making the web better for scientists, we focused on ways that we could make working with Javascript better, like compiling existing scientific libraries to WebAssembly and wrapping them in easy to use JS APIs. When we proposed this to Mozilla’s WebAssembly wizards, they offered a more ambitious idea: if many scientists prefer Python, meet them where they are by compiling the Python science stack to run in WebAssembly.

We thought this sounded daunting — that it would be an enormous project and that it would never deliver satisfactory performance… but two weeks later Mike Droettboom had a working implementation of Python running inside an Iodide notebook. Over the next couple months, we added Numpy, Pandas, and Matplotlib, which are by far the most used modules in the Python science ecosystem. With help from contributors Kirill Smelkov and Roman Yurchak at Nexedi, we landed support for Scipy and scikit-learn. Since then, we’ve continued adding other libraries bit by bit.

Running the Python interpreter inside a Javascript virtual machine adds a performance penalty, but that penalty turns out to be surprisingly small — in our benchmarks, around 1x-12x slower than native on Firefox and 1x-16x slower on Chrome. Experience shows that this is very usable for interactive exploration.

Running Matplotlib in the browser enables its interactive features, which are unavailable in static environments

Bringing Python into the browser creates some magical workflows. For example, you can import and clean your data in Python, and then access the resulting Python objects from Javascript (in most cases, the conversion happens automatically) so that you can display them using JS libraries like d3. Even more magically, you can access browser APIs from Python code, allowing you to do things like manipulate the DOM without touching Javascript.

Of course, there’s a lot more to say about Pyodide, and it deserves an article of its own — we’ll go into more detail in a follow up post next month.

JSMD (JavaScript MarkDown)