Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Gervase Markham: Something You Know And… Something You Know |

The email said:

To better protect your United MileagePlus® account, later this week, we’ll no longer allow the use of PINs and implement two-factor authentication.

This is united.com’s idea of two-factor authentication:

It doesn’t count as proper “Something You Have”, if you can bootstrap any new device into “Something You Have” with some more “Something You Know”.

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/HackingForChrist/~3/2aGgB602xeo/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Foundation Demos August 19 2016 |

Foundation Demos August 19 2016

Foundation Demos August 19 2016

|

|

Air Mozilla: Improving Pytest-HTML: My Outreachy Project |

Ana Ribero of the Outreachy Summer 2016 program cohort describes her experience in the program and what she did to improve Mozilla's Pytest-HTML QA tools.

Ana Ribero of the Outreachy Summer 2016 program cohort describes her experience in the program and what she did to improve Mozilla's Pytest-HTML QA tools.

https://air.mozilla.org/improving-pytest-html-my-outreachy-project/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Webdev Beer and Tell: August 2016 |

Once a month web developers across the Mozilla community get together (in person and virtually) to share what cool stuff we've been working on in...

Once a month web developers across the Mozilla community get together (in person and virtually) to share what cool stuff we've been working on in...

|

|

Mozilla Addons Blog: A Simpler Add-on Review Process |

In 2011, we introduced the concept of “preliminary review” on AMO. Developers who wanted to list add-ons that were still being tested or were experimental in nature could opt for a more lenient review with the understanding that they would have reduced visibility. However, having two review levels added unnecessary complexity for the developers submitting add-ons, and the reviewers evaluating them. As such, we have implemented a simpler approach.

Starting on August 22nd, there will be one review level for all add-ons listed on AMO. Developers who want to reduce the visibility of their add-ons will be able to set an “experimental” add-on flag in the AMO developer tools. This flag won’t have any effect on how an add-on is reviewed or updated.

All listed add-on submissions will either get approved or rejected based on the updated review policy. For unlisted add-ons, we’re also unifying the policies into a single set of criteria. They will still be automatically signed and post-reviewed at our discretion.

We believe this will make it easier to submit, manage, and review add-ons on AMO. Review waiting times have been consistently good this year, and we don’t expect this change to have a significant impact on this. It should also make it easier to work on AMO code, setting up a simpler codebase for future improvements. We hope this makes the lives of our developers and reviewers easier, and we thank you for your continued support.

https://blog.mozilla.org/addons/2016/08/19/a-simpler-add-on-review-process/

|

|

Gervase Markham: Auditing the Trump Campaign |

When we opened our web form to allow people to make suggestions for open source projects that might benefit from a Secure Open Source audit, some joker submitted an entry as follows:

- Project Name: Donald J. Trump for President

- Project Website: https://www.donaldjtrump.com/

- Project Description: Make America great again

- What is the maintenance status of the project? Look at the polls, we are winning!

- Has the project ever been audited before? Its under audit all the time, every year I get audited. Isn’t that unfair? My business friends never get audited.

- …

Ha, ha. But it turns out it might have been a good idea to take the submission more seriously…

If you know of an open source project (as opposed to a presidential campaign) which meets our criteria and might benefit from a security audit, let us know.

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/HackingForChrist/~3/6aV2s8_SWxk/

|

|

Paul Rouget: Servo homebrew nightly buids |

Servo binaries available via Homebrew

See github.com/servo/homebrew-servo

$ brew install servo/servo/servo-bin

$ servo -w http://servo.org # See `servo --help`

Update (every day):

$ brew update && brew upgrade servo-bin

Switch to older version (earliest version being 2016.08.19):

$ brew switch servo-bin YYYY.MM.DD

File issues specific to the Homebrew package here, and Servo issues here.

This package comes without browserhtml.

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: Removing the PowerShell curl alias? |

PowerShell is a spiced up command line shell made by Microsoft. According to some people, it is a really useful and good shell alternative.

Already a long time ago, we got bug reports from confused users who couldn’t use curl from their PowerShell prompts and it didn’t take long until we figured out that Microsoft had added aliases for both curl and wget. The alias had the shell instead invoke its own command called “Invoke-WebRequest” whenever curl or wget was entered. Invoke-WebRequest being PowerShell’s own version of a command line tool for fiddling with URLs.

Invoke-WebRequest is of course not anywhere near similar to neither curl nor wget and it doesn’t support any of the command line options or anything. The aliases really don’t help users. No user who would want the actual curl or wget is helped by these aliases, and user who don’t know about the real curl and wget won’t use the aliases. They were and remain pointless. But they’ve remained a thorn in my side ever since. Me knowing that they are there and confusing users every now and then – not me personally, since I’m not really a Windows guy.

Fast forward to modern days: Microsoft released PowerShell as open source on github yesterday. Without much further ado, I filed a Pull-Request, asking the aliases to be removed. It is a minuscule, 4 line patch. It took way longer to git clone the repo than to make the actual patch and submit the pull request!

It took 34 minutes for them to close the pull request:

“Those aliases have existed for multiple releases, so removing them would be a breaking change.”

To be honest, I didn’t expect them to merge it easily. I figure they added those aliases for a reason back in the day and it seems unlikely that I as an outsider would just make them change that decision just like this out of the blue.

But the story didn’t end there. Obviously more Microsoft people gave the PR some attention and more comments were added. Like this:

“You bring up a great point. We added a number of aliases for Unix commands but if someone has installed those commands on WIndows, those aliases screw them up.

We need to fix this.”

So, maybe it will trigger a change anyway? The story is ongoing…

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2016/08/19/removing-the-powershell-curl-alias/

|

|

Mike Hoye: Culture Shock |

I’ve been meaning to get around to posting this for… maybe fifteen years now? Twenty? At least I can get it off my desk now.

As usual, it’s safe to assume that I’m not talking about only one thing here.

I got this document about navigating culture shock from an old family friend, an RCMP negotiator now long retired. I understand it was originally prepared for Canada’s Department of External Affairs, now Global Affairs Canada. As the story made it to me, the first duty posting of all new RCMP recruits used to (and may still?) be to a detachment stationed outside their home province, where the predominant language spoken wasn’t their first, and this was one of the training documents intended to prepare recruits and their families for that transition.

It was old when I got it 20 years ago, a photocopy of a mimeograph of something typeset on a Selectric years before; even then, the RCMP and External Affairs had been collecting information about the performance of new hires in high-stress positions in new environments for a long time. There are some obviously dated bits – “writing letters back home” isn’t really a thing anymore in the stamped-envelope sense they mean and “incurring high telephone bills”, well. Kids these days, they don’t even know, etcetera. But to a casual search the broad strokes of it are still valuable, and still supported by recent data.

Traditionally, the stages of cross—cultural adjustment have been viewed as a U curve. What this means is, that the first months in a new culture are generally exciting – this is sometimes referred to as the “honeymoon” or “tourist” phase. Inevitably, however, the excitement wears off and coping with the new environment becomes depressing, burdensome, anxiety provoking (everything seems to become a problem; housing, neighbors, schooling, health care, shopping, transportation, communication, etc.) – this is the down part of the U curve and is precisely the period of so-called “culture shock“. Gradually (usually anywhere from 6 months to a year) an individual learns to cope by becoming involved with, and accepted by, the local people. Culture shock is over and we are back, feeling good about ourselves and the local culture.

Spoiler alert: It doesn’t always work out that way. But if you know what to expect, and what you’re looking for, you can recognize when things are going wrong and do something about it. That’s the key point, really: this slow rollercoaster you’re on isn’t some sign of weakness or personal failure. It’s an absolutely typical human experience, and like a lot of experiences, being able to point to it and give it a name also gives you some agency over it you may not have thought you had.

I have more to say about this – a lot more – but for now here you go: “Adjusting To A New Environment”, date of publication unknown, author unknown (likely Canada’s Department of External Affairs.) It was a great help to me once upon a time, and maybe it will be for you.

|

|

Air Mozilla: Intern Presentations 2016, 18 Aug 2016 |

Group 5 of the interns will be presenting on what they worked on this summer. Nathanael Alcock- MV Dimitar Bounov- MV Benoit Chabod- MV Paul...

Group 5 of the interns will be presenting on what they worked on this summer. Nathanael Alcock- MV Dimitar Bounov- MV Benoit Chabod- MV Paul...

|

|

Support.Mozilla.Org: What’s Up with SUMO – 18th August |

Hello, SUMO Nation!

It’s good to be back and know you’re reading these words :-) A lot more happening this week (have you heard about Activate Mozilla?), so go through the updates if you have not attended all our meetings – and do let us know if there’s anything else you want to see in the blog posts – in the comments!

Welcome, new contributors!

If you just joined us, don’t hesitate – come over and say “hi” in the forums!

Contributors of the week

- The forum supporters who helped users out for the last week.

- The writers of all languages who worked on the KB for the last week.

We salute you!

Most recent SUMO Community meeting

- You can read the notes here and see the video at AirMozilla.

The next SUMO Community meeting…

- …is happening on the 24th of August!

- If you want to add a discussion topic to the upcoming meeting agenda:

- Start a thread in the Community Forums, so that everyone in the community can see what will be discussed and voice their opinion here before Wednesday (this will make it easier to have an efficient meeting).

- Please do so as soon as you can before the meeting, so that people have time to read, think, and reply (and also add it to the agenda).

- If you can, please attend the meeting in person (or via IRC), so we can follow up on your discussion topic during the meeting with your feedback.

Community

- Belated HAPPY BIRTHDAY wishes to Safwan, one of our biggest SUMO heroes! If you want to join in, send him a PM here.

- There is a Mozilla Day coming up in Abidjan (Ivory Coast) – if you are around on the 20th of August, join the communit there! Remember that you can find more events on this page.

- PLATFORM REMINDER! The Platform Meetings are BACK! If you missed the previous ones, here is the etherpad, with links to the recordings on AirMo.

- We met with Scott, the project manager for our migration to Lithium – and we are in the process of organizing teams on both sides to kick off the migration process properly.

- Madalina will refresh the meeting agenda to make sure it’s clear, informative, and easily accessible – stay tuned for more details.

- We also started working in “sprints” and the migration is a part of this structure.

- MIGRATION REMINDER: Please take a look at this migration document and use this migration thread to put questions/comments about it for everyone to share and discuss. As much as possible, please try to keep the migration discussion and questions limited to those two places – we don’t want to chase ten different threads in eight different places ;-).

- FINAL REMINDER: Please help us with the audits of existing guidelines and documentation – read and tell us what you think in the following documents:

- Ongoing reminder #1: if you think you can benefit from getting a second-hand device to help you with contributing to SUMO, you know where to find us.

- Ongoing reminder #2: we are looking for more contributors to our blog. Do you write on the web about open source, communities, SUMO, Mozilla… and more? Do let us know!

- Ongoing reminder #3: want to know what’s going on with the Admins? Check this thread in the forum.

Social

- The results for the SUMO Social Day last week were shared out during the Monday Project Meeting.

- Come and sign up for Sprinklr (send an email to mana@mozilla.com or ehull@mozilla.com). We need your help! Use the step-by-step guide here. Take a look at some useful videos:

- A fun fact: the most activity on social channels takes place at 14:00 on Tuesdays and 11:00 on Thursdays (PST).

- Ongoing reminder: We have a training out there for all those interested in Social Support – talk to Madalina or Costenslayer on #AoA (IRC) for more information.

Support Forum

- The SUMO Firefox 48 Release Report is open for feedback: please add your links, tweets, bugs, threads and anything else that you would like to have highlighted in the report.

- More details about the audit for the Support Forum:

- The audit will only be happening this week and next

- It will determine the forum contents that will be kept and/or refreshed

- The Get Involved page will be rewritten and designed as it goes through a “Think-Feel-do” exercis.

- Please take a few minutes this week to read through the document and make a comment or edit.

- One of the main questions is “what are the things that we cannot live without in the new forum?” – if you have an answer, write more in the thread!

- Join Rachel in the SUMO Vidyo room on Friday between noon and 14:00 PST for answering forum threads and general hanging out!

Knowledge Base & L10n

- We are 4 weeks before next release / 2 weeks after current release. What does that mean?

- Joni starts planning and drafting content for the next release; no work for localizers for the next release yet.

- All existing content is open for editing and localization as usual; please focus on localizing the most recent / popular content.

- Reminder: we are following the process/schedule outlined here

- IMPORTANT! Pontoon / user interface update: please do not work on UI strings in Pontoon as we are moving to Lithium – work on localizing articles instead.

- The Brazilian community is rebooting!

- Reminder: Joni has put forward a proposal to update categories for Firefox – read it and tell her what you think!

Firefox

- for Android

- Version 49 will not have many features, but will include bug and security fixes.

- for Desktop

- for iOS

- Version 49 will not have many features, but will include bug and security fixes.

- Version 49 will not have many features, but will include bug and security fixes.

… and that’s it for now, fellow Mozillians! We hope you’re looking forward to a great weekend and we hope to see you soon – online or offline! Keep rocking the helpful web!

https://blog.mozilla.org/sumo/2016/08/18/whats-up-with-sumo-18th-august/

|

|

Chris H-C: The Future of Programming |

Here’s a talk I watched some months ago, and could’ve sworn I’d written a blogpost about. Ah well, here it is:

Bret Victor – The Future of Programming from Bret Victor on Vimeo.

It’s worth the 30min of your attention if you have interest in programming or computer history (which you should have an interest in if you are a developer). But here it is in sketch:

The year is 1973 (well, it’s 2004, but the speaker pretends it is 1973), and the future of programming is bright. Instead of programming in procedures typed sequentially in text files, we are at the cusp of directly manipulating data with goals and constraints that are solved concurrently in spatial representations.

The speaker (Bret Victor) highlights recent developments in the programming of automated computing machines, and uses it to suggest the inevitability of a very different future than we currently live and work in.

It highlights how much was ignored in my world-class post-secondary CS education. It highlights how much is lost by hiding research behind paywalled journals. It highlights how many times I’ve had to rewrite the wheel when, more than a decade before I was born, people were prototyping hoverboards.

It makes me laugh. It makes me sad. It makes me mad.

…that’s enough of that. Time to get back to the wheel factory.

:chutten

https://chuttenblog.wordpress.com/2016/08/18/the-future-of-programming/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Connected Devices Weekly Program Update, 18 Aug 2016 |

Weekly project updates from the Mozilla Connected Devices team.

Weekly project updates from the Mozilla Connected Devices team.

https://air.mozilla.org/connected-devices-weekly-program-update-20160818/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Reps weekly, 18 Aug 2016 |

This is a weekly call with some of the Reps to discuss all matters about/affecting Reps and invite Reps to share their work with everyone.

This is a weekly call with some of the Reps to discuss all matters about/affecting Reps and invite Reps to share their work with everyone.

|

|

Niko Matsakis: 'Tootsie Pop' Followup |

A little while back, I wrote up a tentative proposal I called the

Tootsie Pop

model for unsafe code. It’s safe to say that this

model was not universally popular. =) There was quite a

long and fruitful discussion on discuss. I wanted to write a

quick post summarizing my main take-away from that discussion and to

talk a bit about the plans to push the unsafe discussion forward.

The importance of the unchecked-get use case

For me, the most important lesson was the importance of the unchecked

get

use case. Here the idea is that you have some (safe) code which

is indexing into a vector:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

You have found (by profiling, but of course) that this code is kind of

slow, and you have determined that the bounds-check caused by indexing

is a contributing factor. You can’t rewrite the code to use iterators,

and you are quite confident that the index will always be in-bounds,

so you decide to dip your tie into unsafe by calling

get_unchecked:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Now, under the precise model that I proposed, this means that the

entire containing module is considered to be within an unsafe

abstraction boundary, and hence the compiler will be more conservative

when optimizing, and as a result the function may actually run

slower when you skip the bounds check than faster. (A very similar

example is invoking

str::from_utf8_unchecked,

which skips over the utf-8 validation check.)

Many people were not happy about this side-effect, and I can totally understand why. After all, this code isn’t mucking about with funny pointers or screwy aliasing – the unsafe block is a kind of drop-in replacement for what was there before, so it seems odd for it to have this effect.

Where to go from here

Since posting the last blog post, we’ve started a

longer-term process for settling and exploring a lot of these

interesting questions about the proper use of unsafe. At this point,

we’re still in the data gathering

phase. The idea here is to collect

and categorize interesting examples of unsafe code. I’d prefer at this

point not to be making decisions per se about what is legal or not –

although in some cases someting may be quite unambiguous – but rather

just try to get a good corpus with which we can evaluate different

proposals.

While I haven’t given up on the Tootsie Pop

model, I’m also not

convinced it’s the best approach. But whatever we do, I still believe

we should strive for something that is safe and predictable by

default – something where the rules can be summarized on a

postcard, at least if you don’t care about getting every last bit of

optimization. But, as the unchecked-get example makes clear, it is

important that we also enable people to obtain full optimization,

possibly with some amount of opt-in. I’m just not yet sure what’s the

right setup to balance the various factors.

As I wrote in my last post, I think that we have to expect that whatever guidelines we establish, they will have only a limited effect on the kind of code that people write. So if we want Rust code to be reliable in practice, we have to strive for rules that permit the things that people actually do: and the best model we have for that is the extant code. This is not to say we have to achieve total backwards compatibility with any piece of unsafe code we find in the wild, but if we find we are invalidating a common pattern, it can be a warning sign.

http://smallcultfollowing.com/babysteps/blog/2016/08/18/tootsie-pop-followup/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: HTTP/2 connection coalescing |

Section 9.1.1 in RFC7540 explains how HTTP/2 clients can reuse connections. This is my lengthy way of explaining how this works in reality.

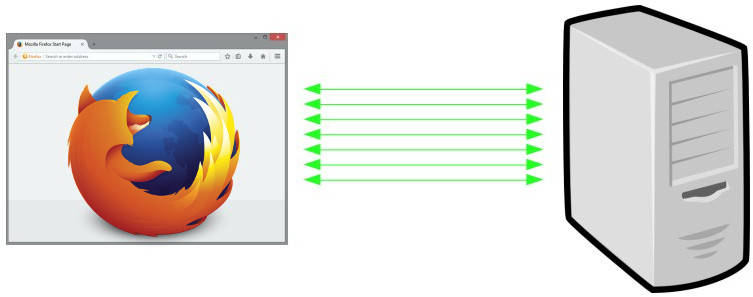

Many connections in HTTP/1

With HTTP/1.1, browsers are typically using 6 connections per origin (host name + port). They do this to overcome the problems in HTTP/1 and how it uses TCP – as each connection will do a fair amount of waiting. Plus each connection is slow at start and therefore limited to how much data you can get and send quickly, you multiply that data amount with each additional connection. This makes the browser get more data faster (than just using one connection).

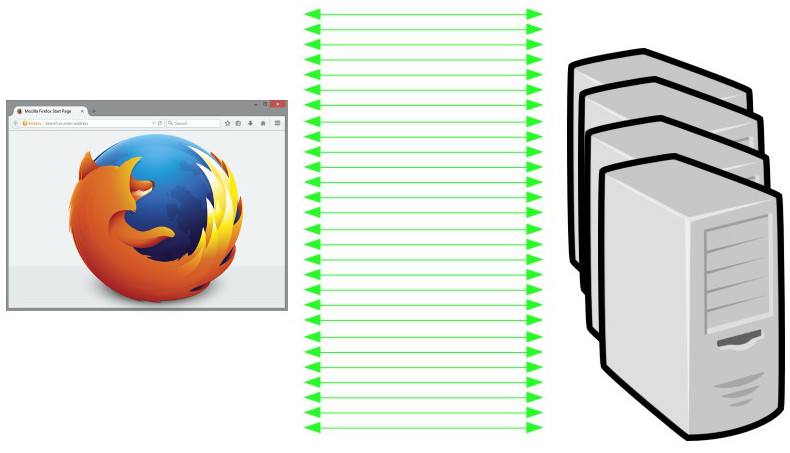

Add sharding

Web sites with many objects also regularly invent new host names to trigger browsers to use even more connections. A practice known as “sharding”. 6 connections for each name. So if you instead make your site use 4 host names you suddenly get 4 x 6 = 24 connections instead. Mostly all those host names resolve to the same IP address in the end anyway, or the same set of IP addresses. In reality, some sites use many more than just 4 host names.

The sad reality is that a very large percentage of connections used for HTTP/1.1 are only ever used for a single HTTP request, and a very large share of the connections made for HTTP/1 are so short-lived they actually never leave the slow start period before they’re killed off again. Not really ideal.

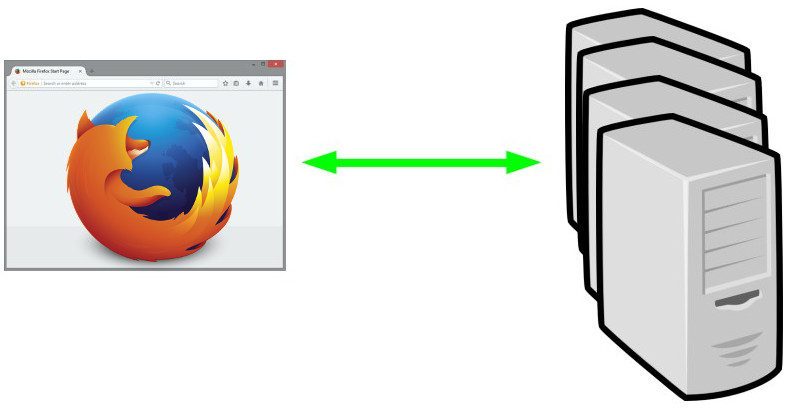

One connection in HTTP/2

With the introduction of HTTP/2, the HTTP clients of the world are going toward using a single TCP connection for each origin. The idea being that one connection is better in packet loss scenarios, it makes priorities/dependencies work and reusing that single connections for many more requests will be a net gain. And as you remember, HTTP/2 allows many logical streams in parallel over that single connection so the single connection doesn’t limit what the browsers can ask for.

Unsharding

The sites that created all those additional host names to make the HTTP/1 browsers use many connections now work against the HTTP/2 browsers’ desire to decrease the number of connections to a single one. Sites don’t want to switch back to using a single host name because that would be a significant architectural change and there are still a fair number of HTTP/1-only browsers still in use.

Enter “connection coalescing”, or “unsharding” as we sometimes like to call it. You won’t find either term used in RFC7540, as it merely describes this concept in terms of connection reuse.

Connection coalescing means that the browser tries to determine which of the remote hosts that it can reach over the same TCP connection. The different browsers have slightly different heuristics here and some don’t do it at all, but let me try to explain how they work – as far as I know and at this point in time.

Coalescing by example

Let’s say that this cool imaginary site “example.com” has two name entries in DNS: A.example.com and B.example.com. When resolving those names over DNS, the client gets a list of IP address back for each name. A list that very well may contain a mix of IPv4 and IPv6 addresses. One list for each name.

You must also remember that HTTP/2 is also only ever used over HTTPS by browsers, so for each origin speaking HTTP/2 there’s also a corresponding server certificate with a list of names or a wildcard pattern for which that server is authorized to respond for.

In our example we start out by connecting the browser to A. Let’s say resolving A returns the IPs 192.168.0.1 and 192.168.0.2 from DNS, so the browser goes on and connects to the first of those addresses, the one ending with “1”. The browser gets the server cert back in the TLS handshake and as a result of that, it also gets a list of host names the server can deal with: A.example.com and B.example.com. (it could also be a wildcard like “*.example.com”)

If the browser then wants to connect to B, it’ll resolve that host name too to a list of IPs. Let’s say 192.168.0.2 and 192.168.0.3 here.

Host A: 192.168.0.1 and 192.168.0.2 Host B: 192.168.0.2 and 192.168.0.3

Now hold it. Here it comes.

The Firefox way

Host A has two addresses, host B has two addresses. The lists of addresses are not the same, but there is an overlap – both lists contain 192.168.0.2. And the host A has already stated that it is authoritative for B as well. In this situation, Firefox will not make a second connect to host B. It will reuse the connection to host A and ask for host B’s content over that single shared connection. This is the most aggressive coalescing method in use.

The Chrome way

Chrome features a slightly less aggressive coalescing. In the example above, when the browser has connected to 192.168.0.1 for the first host name, Chrome will require that the IPs for host B contains that specific IP for it to reuse that connection. If the returned IPs for host B really are 192.168.0.2 and 192.168.0.3, it clearly doesn’t contain 192.168.0.1 and so Chrome will create a new connection to host B.

Chrome will reuse the connection to host A if resolving host B returns a list that contains the specific IP of the connection host A is already using.

The Edge and Safari ways

They don’t do coalescing at all, so each host name will get its own single connection. Better than the 6 connections from HTTP/1 but for very sharded sites that means a lot of connections even in the HTTP/2 case.

curl also doesn’t coalesce anything (yet).

Surprises and a way to mitigate them

Given some comments in the Firefox bugzilla, the aggressive coalescing sometimes causes some surprises. Especially when you have for example one IPv6-only host A and a second host B with both IPv4 and IPv4 addresses. Asking for data on host A can then still use IPv4 when it reuses a connection to B (assuming that host A covers host B in its cert).

In the rare case where a server gets a resource request for an authority (or scheme) it can’t serve, there’s a dedicated error code 421 in HTTP/2 that it can respond with and the browser can then go back and retry that request on another connection.

Starts out with 6 anyway

Before the browser knows that the server speaks HTTP/2, it may fire up 6 connection attempts so that it is prepared to get the remote site at full speed. Once it figures out that it doesn’t need all those connections, it will kill off the unnecessary unused ones and over time trickle down to one. Of course, on subsequent connections to the same origin the client may have the version information cached so that it doesn’t have to start off presuming HTTP/1.

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2016/08/18/http2-connection-coalescing/

|

|

Air Mozilla: 360/VR Meet-Up |

We explore the potential of this evolving medium and update you on the best new tools and workflows, covering: -Preproduction: VR pre-visualization, Budgeting, VR Storytelling...

We explore the potential of this evolving medium and update you on the best new tools and workflows, covering: -Preproduction: VR pre-visualization, Budgeting, VR Storytelling...

|

|

Mitchell Baker: Practicing “Open” at Mozilla |

Mozilla works to bring openness and opportunity for all into the Internet and online life. We seek to reflect these values in how we operate. At our founding it was easy to understand what this meant in our workflow — developers worked with open code and project management through bugzilla. This was complemented with an open workflow through the social media of the day — mailing lists and the chat or “messenger” element, known as Internet Relay Chat (“irc”). The tools themselves were also open-source and the classic “virtuous circle” promoting openness was pretty clear.

Today the setting is different. We were wildly successful with the idea of engineers working in open systems. Today open source code and shared repositories are mainstream, and in many areas the best of practices and expected and default. On the other hand, the newer communication and workflow tools vary in their openness, with some particularly open and some closed proprietary code. Access and access control is a constant variable. In addition, at Mozilla we’ve added a bunch of new types of activities beyond engineering, we’ve increased the number of employees dramatically and we’re a bit behind on figuring out what practicing open in this setting means.

I’ve decided to dedicate time to this and look at ways to make sure our goals of building open practices into Mozilla are updated and more fully developed. This is one of the areas of focus I mentioned in an earlier post describing where I spend my time and energy.

So far we have three early stage pilots underway sponsored by the Office of the Chair:

- Opening up the leadership recruitment process to more people

- Designing inclusive decision-making practices

- Fostering meaningful conversations and exchange of knowledge across the organization, with a particular focus on bettering communications between Mozillians and leadership.

Follow-up posts will have more info about each of these projects. In general the goal of these experiments is to identify working models that can be adapted by others across Mozilla. And beyond that, to assist other Mozillians figure out new ways to “practice open” at Mozilla.

http://blog.lizardwrangler.com/2016/08/17/practicing-open-at-mozilla/

|

|

William Lachance: Herding Automation Infrastructure |

For every commit to Firefox, we run a battery of builds and automated tests on the resulting source tree to make sure that the result still works and meets our correctness and performance quality criteria. This is expensive: every new push to our repository implies hundreds of hours of machine time. However, this type of quality control is essential to ensure that the product that we’re shipping to users is something that we can be proud of.

But what about evaluating the quality of the product which does the building and testing? Who does that? And by what criteria would we say that our automation system is good or bad? Up to now, our procedures for this have been rather embarassingly adhoc. With some exceptions (such as OrangeFactor), our QA process amounts to motivated engineers doing a one-off analysis of a particular piece of the system, filing a few bugs, then forgetting about it. Occasionally someone will propose turning build and test automation for a specific platform on or off in mozilla.dev.planning.

I’d like to suggest that the time has come to take a more systemic approach to this class of problem. We spend a lot of money on people and machines to maintain this infrastructure, and I think we need a more disciplined approach to make sure that we are getting good value for that investment.

As a starting point, I feel like we need to pay closer attention to the following characteristics of our automation:

- End-to-end times from push submission to full completion of all build and test jobs: if this gets too long, it makes the lives of all sorts of people painful — tree closures become longer when they happen (because it takes longer to either notice bustage or find out that it’s fixed), developers have to wait longer for try pushes (making them more likely to just push directly to an integration branch, causing the former problem…)

- Number of machine hours consumed by the different types of test jobs: our resources are large (relatively speaking), but not unlimited. We need proper accounting of where we’re spending money and time. In some cases, resources used to perform a task that we don’t care that much about could be redeployed towards an underresourced task that we do care about. A good example of this was linux32 talos (performance tests) last year: when the question was raised of why we were doing performance testing on this specific platform (in addition to Linux64), no one could come up with a great justification. So we turned the tests off and reconfigured the machines to do Windows performance tests (where we were suffering from a severe lack of capacity).

Over the past week, I’ve been prototyping a project I’ve been calling “Infraherder” which uses the data inside Treeherder’s job database to try to answer these questions (and maybe some others that I haven’t thought of yet). You can see a hacky version of it on my github fork.

Why implement this in Treeherder you might ask? Two reasons. First, Treeherder already stores the job data in a historical archive that’s easy to query (using SQL). Using this directly makes sense over creating a new data store. Second, Treeherder provides a useful set of front-end components with which to build a UI with which to visualize this information. I actually did my initial prototyping inside an ipython notebook, but it quickly became obvious that for my results to be useful to others at Mozilla we needed some kind of real dashboard that people could dig into.

On the Treeherder team at Mozilla, we’ve found the New Relic software to be invaluable for diagnosing and fixing quality and performance problems for Treeherder itself, so I took some inspiration from it (unfortunately the problem space of our automation is not quite the same as that of a web application, so we can’t just use New Relic directly).

There are currently two views in the prototype, a “last finished” view and a “total” view. I’ll describe each of them in turn.

Last finished

This view shows the counts of which scheduled automation jobs were the “last” to finish. The hypothesis is that jobs that are frequently last indicate blockers to developer productivity, as they are the “long pole” in being able to determine if a push is good or bad.

Right away from this view, you can see the mochitest devtools 9 test is often the last to finish on try, with Windows 7 mochitest debug a close second. Assuming that the reasons for this are not resource starvation (they don’t appear to be), we could probably get results into the hands of developers and sheriffs faster if we split these jobs into two seperate ones. I filed bugs 1294489 and 1294706 to address these issues.

Total Time

This view just shows which jobs are taking up the most machine hours.

Probably unsurprisingly, it seems like it’s Android test jobs that are taking up most of the time here: these tests are running on multiple layers of emulation (AWS instances to emulate Linux hardware, then the already slow QEMU-based Android simulator) so are not expected to have fast runtime. I wonder if it might not be worth considering running these tests on faster instances and/or bare metal machines.

Linux32 debug tests seem to be another large consumer of resources. Market conditions make turning these tests off altogether a non-starter (see bug 1255890), but how much value do we really derive from running the debug version of linux32 through automation (given that we’re already doing the same for 64-bit Linux)?

Request for comments

I’ve created an RFC for this project on Google Docs, as a sort of test case for a new process we’re thinking of using in Engineering Productivity for these sorts of projects. If you have any questions or comments, I’d love to hear them! My perspective on this vast problem space is limited, so I’m sure there are things that I’m missing.

|

|

Mike Hoye: The Future Of The Planet |

I’m not sure who said it first, but I’ve heard a number of people say that RSS solved too many problems to be allowed to live.

I’ve recently become the module owner of Planet Mozilla, a venerable communication hub and feed aggregator here at Mozilla. Real talk here: I’m not likely to get another chance in my life to put “seize control of planet” on my list of quarterly deliverables, much less cross it off in less than a month. Take that, high school guidance counselor and your “must try harder”!

I warned my boss that I’d be milking that joke until sometime early 2017.

On a somewhat more serious note: We have to decide what we’re going to do with this thing.

Planet Mozilla is a bastion of what’s by now the Old Web – Anil Dash talks about it in more detail here, the suite of loosely connected tools and services that made the 1.0 Web what it was. The hallmarks of that era – distributed systems sharing information streams, decentralized and mutually supportive without codependency – date to a time when the economics of software, hardware, connectivity and storage were very different. I’ve written a lot more about that here, if you’re interested, but that doesn’t speak to where we are now.

Please note that when talk about “Mozilla’s needs” below, I don’t mean the company that makes Firefox or the non-profit Foundation. I mean the mission and people in our global community of communities that stand up for it.

I think the following things are true, good things:

- People still use Planet heavily, sometimes even to the point of “rely on”. Some teams and community efforts definitely rely heavily on subplanets.

- There isn’t a better place to get a sense of the scope of Mozilla as a global, cultural organization. The range and diversity of articles on Planet is big and weird and amazing.

- The organizational and site structure of Planet speaks well of Mozilla and Mozilla’s values in being open, accessible and participatory.

- Planet is an amplifier giving participants and communities an enormous reach and audience they wouldn’t otherwise have to share stories that range from technical and mission-focused to human and deeply personal.

These things are also true, but not all that good:

- It’s difficult to say what or who Planet is for right now. I don’t have and may not be able to get reliable usage metrics.

- The egalitarian nature of feeds is a mixed blessing: On one hand, Planet as a forum gives our smallest and most remote communities the same platform as our executive leadership. On the other hand, headlines ranging from “Servo now self-aware” and “Mozilla to purchase Alaska” to “I like turnips” are all equal citizens of Planet, sorted only by time of arrival.

- Looking at Planet via the Web is not a great experience; if you’re not using a reader even to skim, you’re getting a dated user experience and missing a lot. The mobile Web experience is nonexistent.

- The Planet software is, by any reasonable standards, a contraption. A long-running and proven contraption, for sure, but definitely a contraption.

Maintaining Planet isn’t particularly expensive. But it’s also not free, particularly in terms of opportunity costs and user-time spent. I think it’s worth asking what we want Planet to accomplish, whether Planet is the right tool for that, and what we should do next.

I’ve got a few ideas about what “next” might look like; I think there are four broad categories.

- Do nothing. Maybe reskin the site, move the backing repo from Subversion to Github (currently planned) but otherwise leave Planet as is.

- Improve Planet as a Planet, i.e: as a feed aggregator and communication hub.

- Replace Planet with something better suited to Mozilla’s needs.

- Replace Planet with nothing.

I’m partial to the “Improve Planet as a Planet” option, but I’m spending a lot of time thinking about the others. Not (or at least not only) because I’m lazy, but because I still think Planet matters. Whatever we choose to do here should be a use of time and effort that leaves Mozilla and the Web better off than they are today, and better off than if we’d spent that time and effort somewhere else.

I don’t think Planet is everything Planet could be. I have some ideas, but also don’t think anyone has a sense of what Planet is to its community, or what Mozilla needs Planet to be or become.

I think we need to figure that out together.

Hi, Internet. What is Planet to you? Do you use it regularly? Do you rely on it? What do you need from Planet, and what would you like Planet to become, if anything?

These comments are open and there’s a thread open at the Mozilla Community discourse instance where you can talk about this, and you can always email me directly if you like.

Thanks.

* – Mozilla is not to my knowledge going to purchase Alaska. I mean, maybe we are and I’ve tipped our hand? I don’t get invited to those meetings but it seems unlikely. Is Alaska even for sale? Turnips are OK, I guess.

http://exple.tive.org/blarg/2016/08/17/the-future-of-the-planet/

|

|