Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

About:Community: Firefox 74 new contributors |

With the release of Firefox 74, we are pleased to welcome the 29 developers who contributed their first code change to Firefox in this release, 27 of whom were brand new volunteers! Please join us in thanking each of these diligent and enthusiastic individuals, and take a look at their contributions:

- jpmohr: 1599731

- louiscontant: 1598447

- mforney: 1157850, 1611536, 1611565, 1612025

- sanchit.arora.2002: 1602048, 1605876

- tds803: 1613257

- Arno Renevier: 1608911

- Arnout Engelen: 1612667

- Ashu Ghildiyal: 1613858

- Asumu Takikawa: 1608772

- Brandon Kraft: 1609807

- Chris Henry: 1604970

- Elad Zelingher: 1566755

- Jon Bauman: 1611431, 1614097

- Khushal Sahni: 1604143

- Kousuke Takaki: 1542975, 1602088, 1613094

- Mahak: 1208906, 1603100

- Martin McNickle: 1349658, 1593772, 1611043, 1611044, 1611829

- Michael Wilson: 1605874

- Nicol`o Ribaudo: 1607050

- Nikolai Lopin: 1484256

- Pranav pandey: 1517969, 1593607, 1604115

- Richard Matheson: 1102584

- Rob: 1604066, 1605263, 1608183

- Sakura Mochizuki: 1611040

- Samarjeet: 1612956

- Sawyer Bergeron: 1605755

- Stefan Hindli: 1611264

- Thomas Dolezal: 1611041, 1611733, 1612143, 1612146, 1612148

- Victoria Wang: 1606990

- naktinis: 1532722

https://blog.mozilla.org/community/2020/03/06/firefox-74-new-contributors/

|

|

Karl Dubost: Week notes - 2020 w08 - worklog - pytest is working |

(late publishing on March 6, 2020)

Diagnosis

last Friday, Monday and Tuesday have led some interesting new issues.

- youtube users on firefox could not see a 3d navigation widget, it came out that Firefox had a bug about the default value of ATTACHED_SHADERS in WebGL and it is now fixed. Very quick turnaround and good success story for webcompat.

- stacking contexts in between firefox, chrome, edge (pre-chromium) and safari have different behaviors. Daniel opened an issue about the stacking contexts differences.

- some of the issues are harder to test. For example, everything related to instagram and facebook, if you do not have a personal active account will be canned at a point. Testing accounts shared in between people of different countries are quickly killed.

- probably a race issue.

- weird junky animation with webgl on canvas

- svg animations defined in

defsare not working the same in chrome, safari and firefox. - downloading files on fenix is still not a good story.

- location being requested all the time, this is a dupe

- we are still seing sites with ill-defined user agent sniffing both client side and server side.

- sometimes tracking protection breaks stuff.

pytest

A couple of months ago i had a discussion about unittests and nosetests with friends. On webcompat.com we are using nose (nosetests) to run the tests. My friends encouraged me to switch to pytest. I didn't have yet the motivation to do it. But last week, I started to look at it. And I finally landed this week the pull request for switching to pytest. I didn't convert all tests. This will be done little by little when touching the specific tests. The tests are running as-is, so there's not much benefits to change them at this point.

Hello modernity.

Otsukare!

|

|

Mozilla VR Blog: Jumpy Balls, a little demo Showcasing ecsy-three |

If you have a VR headset, go to https://mixedreality.mozilla.org/jumpy-balls/ and try the game!

Jumpy Balls is a simple game where you have to guide balls shot from a cannon towards a target. Use your controllers to drag blocks with different physical properties, making the balls bounce and reach their goal.

Behind Jumpy Balls

Developing a 3D application is a complex task. While 3D engines like three.js provide a solid foundation, there are still many different systems that must work together (eg: app states, flow, logic, collisions, physics, UI, IA, sound…), and you probably do not want to rebuild all this from scratch on each project.

Also, when creating a small experiment or simple technical demo (like those at https://threejs.org/examples), disparate parts of an application can be managed in an ad-hoc manner. But as the software grows with more interactions, a richer UI, and more user feedback, the increased complexity demands a better strategy to coordinate modules and state.

We created ECSY to help organize all of this architecture of more complex applications and ECSY-Three to ease the process when working with the three.js engine.

The technologies we used to develop Jumpy Balls were:

- ecsy and ecsy-three for renderer and logic

- ammo.js for physics

- Blender and glTF for all models and animations.

- Audacity for sound effects.

- Madtracker for the awesome music by Jose Manuel Perez (aka JosSs)

- ECSY developer tools, which have proven to be really useful when debugging and especially detecting leaks on the life cycle of the entities and components.

The ecsy-three Module

We created ecsy-three to facilitate developing applications using ECSY and three.js. It is a set of components, systems, and helpers that will (eventually) include a large number of reusable components for the most commonly used patterns when developing 3D applications.

The ecsy-three module exports an initialize() function that creates the entities that you will commonly need in a three.js application: scene, camera and renderer.

// Create a new world to hold all our entities and systems

world = new World();

// Initialize the default sets of entities and systems

let data = initialize(world, {vr: true});

And data will have the following structure, letting you access the created entities:

{

world,

entities: {

scene,

camera,

cameraRig,

renderer,

renderPass

}

}

It will also initialize internally the systems that will take care of common tasks such as updating the transforms of the objects, listening for changes on the cameras, and of course, rendering the scene.

Please notice that you can always modify that behaviour if needed and create the entities by yourself.

Once you get the initialized entities, you can modify them. For example, changing the camera position:

// Grab the initialized entities

let {scene, renderer, camera} = data.entities;

// Modify the position for the default camera

let transform = camera.getMutableComponent(Transform);

transform.position.z = 40;

You could then create a textured box using the standard three.js API:

// Create a three.js textured box

var texture = new THREE.TextureLoader().load( 'textures/crate.gif' );

var geometry = new THREE.BoxBufferGeometry( 20, 20, 20 );

var material = new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial( { map: texture } );

mesh = new THREE.Mesh( geometry, material );

And to include that box into the ECSY world, we just create a new entity and attach the Object3D component to it:

var rotatingBox = world.createEntity()

.addComponent(Object3D, { value: mesh })

Once we have the entity created we can add new components to modify its behaviour, for example by creating a custom component called Rotating that will be used to identify all the objects that will be rotating on our scene:

rotatingBox.addComponent(Rotating);

And now we can implement a system that queries the entities with a Rotating component and rotate them:

class RotationSystem extends System {

execute(delta) {

this.queries.entities.results.forEach(entity => {

var rotation = entity.getMutableComponent(Transform).rotation;

rotation.x += 0.5 * delta;

rotation.y += 0.1 * delta;

});

}

}

RotationSystem.queries = {

entities: {

components: [Rotating, Transform]

}

};

# ```For more info please visit the ecsy-three repository.

At this point in the development of ecsy-three, we have not defined yet all the components and systems that will be part of it, as we are following these goals:

- Keeping the components and systems as simple as possible, implementing just the minimum functionality, so they can be used as small building blocks that can be combined together with each other to build more complex components versus mega components (and systems) very opinionated.

- Add components and systems as we need them, based on our real needs of real examples, like Jumpy Balls, versus premature overengineering.

- Verbosity over unnecessary abstraction and syntactic sugars.

This does not mean that in the future ecsy-three will not contain larger, more abstract and complex modules and syntactic sugar that accelerates programming in ecsy-three. Simply that moment has not arrived, we are still at an early stage.

What’s next

We will also bet on improving the ecosystem around Blender, so that the integration between Blender and the ecsy’s components and three.js is more comfortable and transparent, to avoid unneeded intermediate steps or “hacks” from the creation of an asset in Blender until we can use it in our application.

Feel free to join the discussions at:

|

|

Mozilla Addons Blog: Extensions in Firefox 74 |

Welcome to another round of updates from Firefox Add-ons in Firefox 74. Here is what our community has been up to:

- Keyboard shortcuts using the commands API can now be unset by setting them to an empty string using commands.update. Users can also do so manually via the new shortcut removal control at

about:addons. (Thanks, Rob) - There were some issues with long browserAction badge texts wrapping incorrectly. The badge text supports three characters, a fourth may fit in depending on the letters used. Everything else will be cropped. Please keep this in mind when setting your badge text (Thank you Brian)

- The global theme is not reset using themes.reset unless the current global theme was created by the extension (Kudos to you, Ajitesh)

- An urlClassification value was added to webRequest to give insight into how the URLs were classified by Firefox. (Hurrah, Shane)

- The

extensions.webextensions.remotepreference will only be read once. If you are changing this preference, the browser needs to be restarted for it to apply. This preference is used to disable out-of-process extensions, which is an unsupported configuration. The preference will be removed in a future update (bug 1613141).

We’ll be back for more in a few weeks when Firefox 75 is on the horizon. If you’d like to help make this list longer, please consider contributing to add-ons in Firefox. I’d be excited to feature your changes next time.

The post Extensions in Firefox 74 appeared first on Mozilla Add-ons Blog.

https://blog.mozilla.org/addons/2020/03/05/extensions-in-firefox-74/

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Four tips to refresh your relationship status with social media |

Can you even remember a world before selfies or memes? Things have escalated quickly. Social media has taken over our lives and, for better or worse, become an extension of … Read more

The post Four tips to refresh your relationship status with social media appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

|

|

Mike Hommey: Standing up the Cross-Compilation of Firefox for Windows on Linux |

I’ve spent the past few weeks, and will spend the next few weeks, setting up cross-compiled builds of Firefox for Windows on Linux workers on Mozilla’s CI. Following is a long wall of text, if that’s too much for you, you may want to check the TL;DR near the end. If you’re a Windows user wondering about the Windows Subsystem for Linux, please at least check the end of the post.

What is it?

Traditionally, compiling software happens mostly on the platform it is going to run on. Obviously, this becomes less true when you’re building software that runs on smartphones, because you’re usually not developing on said smartphone. This is where Cross-Compilation comes in.

Cross-Compilation is compiling for a platform that is not the one you’re compiling on.

Cross-Compilation is less frequent for desktop software, because most developers will be testing the software on the machine they are building it with, which means building software for macOS on a Windows PC is not all that interesting to begin with.

Continuous Integration, on the other hand, in the era of “build pipelines”, doesn’t necessarily care that the software is built in the same environment as the one it runs on, or is being tested on.

But… why?

Five years ago or so, we started building Firefox for macOS on Linux. The main drivers, as far as I can remember, were resources and performance, and they were both tied: the only (legal) way to run macOS in a datacenter is to rack… Macs. And it’s not like Apple had been producing rackable, server-grade, machines. Okay, they have, but that didn’t last. So we were using aging Mac minis. Switching to Linux machines led to faster compilation times, and allowed to recycle the Mac minis to grow the pool running tests.

But, you might say, Windows runs on standard, rackable, server-grade machines. Or on virtually all cloud providers. And that is true. But for the same hardware, it turns out Linux performs better (more on that below), and the cost per hour per machine is also increased by the Windows license.

But then… why only now?

Firefox has a legacy of more than 20 years of development. That shows in its build system. All the things that allow cross-compiling Firefox for Windows on Linux only lined up recently.

The first of them is the compiler. You might interject with “mingw something something”, but the reality is that binary compatibility for accessibility (screen readers, etc.) and plugins (Flash is almost dead, but not quite) required Microsoft Visual C++ until recently. What changed the deal is clang-cl, and Mozilla has stopped using MSVC for the builds of Firefox it ships with Firefox 63, about 20 months ago. , Another is the process of creating the symbol files used to process crash reports, which was using one of the tools from breakpad to dump the debug info from PDB files in the right format. Unfortunately, that was using a Windows DLL to do so. What recently changed is that we now have a platform-independent tool to do this, that doesn’t require that DLL. And to place credit where credit is due, this was thanks to the people from Sentry providing Rust crates for most of the pieces necessary to do so.

Another is the build system itself, which assumed in many places that building for Windows meant you were on Windows, which doesn’t help cross-compiling for Windows. But worse than that, it also assumed that the compiler was similar. This worked fine when cross-compiling for Android or MacOS on Linux because compiling tools for the build itself (most notably a clang plugin) and compiling Firefox use compatible compilers, that take the same kind of arguments. The story is different when one of the compilers is clang, which has command line arguments like GCC, and the other is clang-cl, which has command line arguments like MSVC. This changed recently with work to allow building Android Geckoview on Windows (I’m not entirely sure all the pieces for that are there just yet, but the ones in place surely helped me ; I might have inadvertently broken some things, though).

So how does that work?

The above is unfortunately not the whole story, so when I started looking a few weeks ago, the idea was to figure out how far off we were, and what kind of shortcuts we could take to make it happen.

It turns out we weren’t that far off, and for a few things, we could work around by… just running the necessary Windows programs with Wine with some tweaks to the build system (Ironically, that means the tool to create symbol files didn’t matter). For others… more on that further below.

But let’s start looking how you could try this for yourself, now that blockers have been fixed.

First, what do you need?

- A copy of Microsoft Visual C++. Unfortunately, we still need some of the tools it contains, like the assembler, as well as the platform development files.

- A copy of the Windows 10 SDK.

- A copy of the Windows Debug Interface Access (DIA) SDK.

- A good old VFAT filesystem, large enough to hold a copy of all the above.

- A WOW64-supporting version of Wine (wine64).

- A full install of clang, including clang-cl (it usually comes along).

- A copy of the Windows version of clang-cl (yes, both a Linux clang-cl and a Windows clang-cl are required at the moment, more on this further below).

Next, you need to setup a .mozconfig that sets the right target:

ac_add_options --target=x86_64-pc-mingw32(Note: the target will change in the future)

You also need to set a few environment variables:

WINDOWSSDKDIR, with the full path to the base of the Windows 10 SDK in your VFAT filesystem.DIA_SDK_PATH, with the full path to the base of the Debug Interface Access SDK in your VFAT filesystem.

You also need to ensure all the following are reachable from your $PATH:

wine64ml64.exe(somewhere in the copy of MSVC in your VFAT filesystem, under aHostx64/x64directory)clang-cl.exe(you also need to ensure it has the executable bit set)

And I think that’s about it. If not, please leave a comment or ping me on Matrix (@glandium:mozilla.org), and I’ll update the instructions above.

With an up-to-date mozilla-central, you should now be able to use ./mach build, and get a fresh build of Firefox for 64-bits Windows as a result (Well, not right now as of writing, the final pieces only just landed on autoland, they will be on mozilla-central in a few hours).

What’s up with that VFAT filesystem?

You probably noticed I was fairly insistive about some things being in a VFAT filesystem. The reason is filesystem case-(in)sensitivity. As you probably know, filesystems on Windows are case-insensitive. If you create a file Foo, you can access it as foo, FOO, fOO, etc.

On Linux, filesystems are most usually case-sensitive. So when some C++ file contains #include "windows.h" and your filesystem actually contains Windows.h, things don’t align right. Likewise when the linker wants kernel32.lib and you have kernel32.Lib.

Ext4 recently gained some optional case-insensitivity, but it requires a very recent kernel, and doesn’t work on existing filesystems. VFAT, however, as supported by Linux, has always(?) been case-insensitive. It is the simpler choice.

There’s another option, though, in the form of FUSE filesystems that wrap an existing directory to expose it as case-insensitive. That’s what I tried first, actually. CIOPFS does just that, with the caveat that you need to start from an empty directory, or an all-lowercase directory, because files with any uppercase characters in their name in the original directory don’t appear in the mountpoint at all. Unfortunately, the last version, from almost 9 years ago doesn’t withstand parallelism: when several processes access files under the mountpoint, one or several of them get failures they wouldn’t otherwise get if they were working alone. So during my first attempts cross-building Firefox I was actually using -j1. Needless to say, the build took a while, but it also made it more obvious when I hit something broken that needed fixing.

Now, on Mozilla CI, we can’t really mount a VFAT filesystem or use FUSE filesystems that easily. Which brings us to the next option: LD_PRELOAD. LD_PRELOAD is an environment variable that can be set to tell the dynamic loader (ld.so) to load a specified library when loading programs. Which in itself doesn’t do much, but the symbols the library exposes will take precedence over similarly named symbols from other libraries. Such as libc.so symbols. Which allows to divert e.g. open, opendir, etc. See where this is going? The library can divert the functions programs use to access files and change the paths the programs are trying to use on the fly.

Such libraries do exist, but I had issues with the few I tried. The most promising one was libcasefold, but building its dependencies turned out to be more work than it should have been, and the hooking it does via libsyscall_intercept is more hardcore than what I’m talking about above, and I wasn’t sure we wanted to support something that hotpatches libc.so machine code at runtime rather than divert it.

The result is that we now use our own, written in Rust (because who wants to write bullet-proof path munging code in C?). It can be used instead of a VFAT filesystem in the setup described above.

So what’s up with needing clang-cl.exe?

One of the tools Firefox needs to build is the MIDL compiler. To do its work, the MIDL compiler uses a C preprocessor, and the Firefox build system makes it use clang-cl. Something amazing that I discovered while working on this is that Wine actually supports executing Linux programs from Windows programs. So it looked like it was going to be possible to use the Linux clang-cl for that. Unfortunately, that doesn’t quite work the same way executing a Windows program does from the parent process’s perspective, and the MIDL compiler ended up being unable to read the output from the preprocessor.

Technically speaking, we could have made the MIDL compiler use MSVC’s cl.exe as a preprocessor, since it conveniently is in the same directory as ml64.exe, meaning it is already in $PATH. But that would have been a step backwards, since we specifically moved off cl.exe.

Alternatively, it is also theoretically possible to compile with --disable-accessibility to avoid requiring the MIDL compiler at all, but that currently doesn’t work in practice. And while that would help for local builds, we still want to ship Firefox with accessibility on.

What about those compilation times, then?

Past my first attempts at -j1, I was able to get a Windows build on my Linux machine in slightly less than twice the time for a Linux build, which doesn’t sound great. Several things factor in this:

- the build system isn’t parallelizing many of the calls to the MIDL compiler, and in practice that means the build sits there doing only that and nothing else (there are some known inefficiencies in the phase where this runs).

- the build system isn’t parallelizing the calls to the Effect compiler (FXC), and this has the same effect on build times as the MIDL compiler above.

- the above two wouldn’t actually be that much of a problem if … Wine wasn’t slow. When running full fledged applications or games, it really isn’t, but there is a very noticeable overhead when running a lot of short-lived processes. That accumulates to several minutes over a full Firefox compilation.

That third point may or may not be related to the version of Wine available in Debian stable (what I was compiling on), or how it’s compiled, but some lucky accident made things much faster on my machine.

See, we actually already have some Windows cross-compilation of Firefox on Mozilla CI, using mingw. Those were put in place to avoid breaking Tor Browser, because that’s how they build for Windows, and because not breaking the Tor Browser is important to us. And those builds are already using Wine for the Effect compiler (FXC).

But the Wine they use doesn’t support WOW64. So one of the first things necessary to setup 64-bits Windows cross-builds with clang-cl on Mozilla CI was to get a WOW64-supporting Wine. Following the Wine build instructions was more or less straightforward, but I hit a snag: it wasn’t possible to install the freetype development files for both the 32-bits version and the 64-bits version because the docker images where we build Wine are still based on Debian 9 for reasons, and the freetype development package was not multi-arch ready on Debian 9, while it now is on Debian 10.

Upgrading to Debian 10 is most certainly possible, but that has a ton more implications than what I was trying to achieve is supposed to. You might ask “why are you building Wine anyways, you could use the Debian package”, to which I’d answer “it’s a good question, and I actually don’t know. I presume the version in Debian 9 was too old (it is older than the one we build)”.

Anyways, in the moment, while I happened to be reading Wine’s configure script to get things working, I noticed the option --without-x and thought “well, we’re not running Wine for any GUI stuff, how about I try that, that certainly would make things easy”. YOLO, right?

Not only did it work, but testing the resulting Wine on my machine, compilation times were now down to only be 1 minute slower than a Linux build, rather than 4.5 minutes! That was surely good enough to go ahead and try to get something running on CI.

Tell us about those compilation times already!

I haven’t given absolute values so far, mainly because my machine is not representative (I’ll have a blog post about that soon enough, but you may have heard about it on Twitter, IRC or Slack, but I won’t give more details here), and because the end goal here is Mozilla automation, for both the actual release of Firefox (still a long way to go there), and the Try server. Those are what matters more to my fellow developers. Also, I actually haven’t built under Windows on my machine for a fair comparison.

So here it comes:

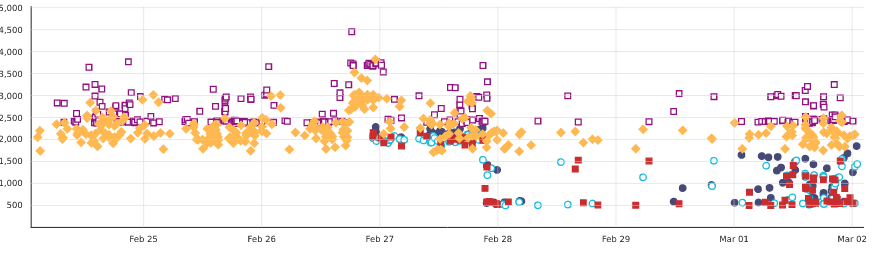

Let’s unwrap a little:

- The yellowish and magenta points are native Windows “opt” builds, on two different kinds of AWS instances.

- The other points are Cross-Compilations with the same “opt” configuration on three different kinds of AWS instances, one of which is the same as one used for Windows, and another one having better I/O than all the others (the cyan circles).

- We use a tool to share a compilation cache between builds on automation (sccache), which explains the very noisy nature of the build times, because they depend on the amount of source code changes and of the cache misses they induce.

- The Cross-Compiled builds were turned on around the 27th of February and started about as fast as the native Windows builds were at the beginning of the graph, but they had just seen a regression.

- The regression was due to a recent change that made the clang plugin change in every build, which led to large numbers of cache misses.

- After fixing the regression, the build times came back to their previous level on the native jobs.

- Sccache handled clang-cl arguments in a way that broke cross-compilation, so when we turned on the cross-compiled jobs on automation, they actually had the cache turned off!

- Let me state this explicitly because that wasn’t expected at all: the cross-compiled jobs WITHOUT a cache were as fast as native jobs WITH a cache!

- A day later, after fixing sccache, we turned it on for the cross-compiled jobs, and build times dropped.

- The week-end passed, and with more realistic work loads where actual changes to compiled code happen and invalidate parts of the cache, build times get more noisy but stay well under what they are on native Windows.

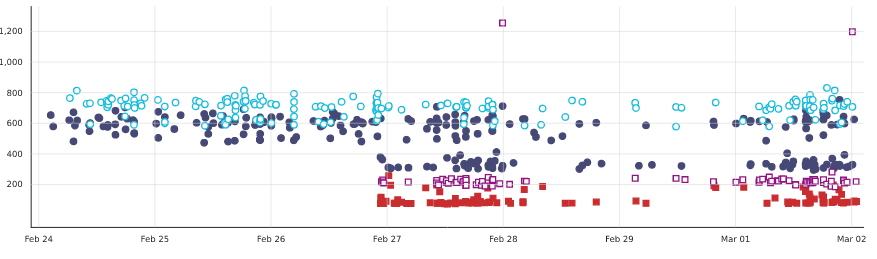

But the above only captures build times. On automation, a job does actually more than build. It also needs to get the source code, and install the tools needed to build. The latter is unfortunately not tracked at the moment, but the former is:

Now, for some explanation of the above graph:

Now, for some explanation of the above graph:

- The colors don’t match the previous graph. Sorry about that.

- The colors vary by AWS instance type, and there is no actual distinction between Windows and Linux, so the instance type that is shared between them has values for both, which explain why it now looks bimodal.

- It can be seen that the ones with better I/O (in red) are largely faster to get the source code, but also that for the shared instance type, Linux is noticeably faster.

It would be fair to say that independently of Windows vs. Linux, way too much time is spent getting the source code, and there’s other ongoing work to make things better.

TL;DR

Overall, the fast end of native Windows builds on Mozilla CI, including Try server, is currently around 45 minutes. That is the time taken by the entire job, and the minimum time between a developer pushing and Windows tests starting to run.

With Cross-Compilation, the fast end is, as of writing, 13 minutes, and can improve further.

As of writing, no actual Windows build job has switched over to Cross-compilation yet. Only an experimental, tier 2, job has been added. But the main jobs developers rely on on the Try server are going to switch real soon now (opt and debug for 32-bits, 64-bits and aarch64). Running all the test suites on Try against them yields successful results (modulo the usual known intermittent failures).

(opt and debug for 32-bits, 64-bits and aarch64). Running all the test suites on Try against them yields successful results (modulo the usual known intermittent failures).

Actually shipping off Cross-compiled builds will take longer. We first need to understand the extent of the differences with the native builds and be confident that no subtle breakage happens. Also, PGO and LTO haven’t been tested so far. Everything will come in time.

What about Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL)?

The idea to allow developers on Windows to build Firefox from WSL has floated for a while. The work to stand up Cross-compiled builds on automation has brought us the closest ever to actually being able to do it! If you’re interested in making it pass the finish line, please come talk to me in #build:mozilla.org on Matrix, there shouldn’t be much work left and we can figure it out (essentially, all the places using Wine would need to do something else, and… that’s it(?)). That should yield faster build times than natively with MozillaBuild.

|

|

Robert Kaiser: Picard Filming Sites: Season 1, Part 1 |

This has gone as far as me doing several presentations about the topic - two of which (one in German, one in English language) I will give at this year's FedCon as well, and creating an experimental website at filmingsites.com where I note all locations used in Star Trek productions as soon as I become aware of them.

In the last few years, around the Star Trek Las Vegas Conventions, I did get the chance to have a few days traveling around Los Angeles and vicinity, visit a few locations and take pictures there. And after Discovery being filmed up in the Toronto area (and generally using quite few locations outside the studios), Picard is back producing in Southern California and using plenty of interesting places! And now with the first half of season 1 in the books (or at least ready to watch for us via streaming), here are a few filming sites I found in those episodes:

And we actually get started with our first location (picture is a still from the series) in "Remembrance" right after Picard wakes up from the "cold open" dream sequence: Ch^ateau Picard was filmed at Sunstone Winery's Villa this time (after different places were used in its TNG appearances). The Winery's general manager even said "We encourage all the Trekkies and Trekkers to come visit us." - so I guess I'll need to put it in my travels plans soon.

Another one I haven't seen yet but will need to put in my plans to see is One Culver, previously known as Sony Pictures Plaza. That's where the scenes in the Daystrom Institute were shot - interestingly, in walking distance to the location of the former Desilu Culver soundstages (now "The Culver Studios") and its backlot (now a residential area), where the original Star Trek series shot its first episodes and several outdoor scenes of later ones as well. One Culver's big glass front structure and the huge screen on its inside are clearly visible multiple times in Picard's Daystrom Institute scenes, as is the rainbow arch behind it on the Sony Studios parking lot. Not having been there, I could only include a promotional picture from their website here.

Now a third filming site that appears in "Remembrance" is actually one I do have my own pictures of: After seeing the first trailer for Picard and getting a hint where that building depicted that clip is, I made my way last summer to a place close to Disneyland and took a few pictures of Anaheim Convention Center. Walking by to the main entrance, I found the attached Arena to just look good, so I also got one shot of that one in - and then I see that in this episode, they used it as the Starfleet Archive Museum!

Of course, in the second episode, "Maps and Legends", we then see the main entrance, where Picard goes to meet the C-in-C, so presumably Starfleet headquarters. It looks like the roof scenes with Dahj would actually be on the same building, on satellite pictures, there seems to be an area with those stairs South of the main entrance. I'm still a bit sad though that Starfleet seems to have moved their headquarters and it's not the Tillman administration building any more that was used in previous series (actually, for both headquarters and the Academy - so maybe it comes back in some series as the Academy, with its beautiful Japanese garden).

Of course, at the end of this episode we get to Raffi's home, and we stay there for a bit and see more of it in "The End is the Beginning". The description in the episode tells us it's located at a place called "Vasquez Rocks" - and this time, that's actually the real filming site! Now, Trekkies know this of course, as a whole lot of Trek has been filmed there - most famously the fight between Kirk and the Gorn captain in "Arena. Vasquez Rocks has surely been of the most-used Star Trek filming sites over the years, though - at least before Picard - I'd say that it ranked second behind Bronson Canyon. How what's nowadays a Natural Area park becomes a place to live in by 2399 is up to anyone's speculation.

I guess in the 3 introductory episodes we had more different filming sites than in any of the two whole seasons of Discovery seen so far, but right in the next episode, Absolute Candor, we got yet another interesting place! A lot of that episode plays on the planet Vashti, with three sets of scenes on their main place with the bar setting: In the "cold open" / flashback, when Picard beams down to the planet again in the show's present, and before he leaves, including the fight scene. Given that there were multiple hints of shooting taking place at Universal Studios Hollywood, and the sets having a somewhat familiar look, more Mexican than totally alien, it did not take long to identify where those scenes were filmed: It's the standing "Mexican Street" / "Old Mexico Place" set on Universal's backlot - which you usually can visit with the Studio Tour as an attraction of their Theme Park. The pictures, of the bar area, and basically from there in the direction of Picard's beam-in point, are from a one of those tours I took in 2013.

In the following two episodes, I could not make out any filming sites, so I guess they pretty much filmed those at Santa Clarita Studios where the production of the series is based. I know we will have some location(s) to talk about in the second half of the season though - not sure if there's as many as in the first few episodes, but I hope we'll have a few good ones!

https://home.kairo.at/blog/2020-03/picard_filming_sites_season_1_part_1

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Future-proofing Firefox’s JavaScript Debugger Implementation |

Or: The Implementation of the SpiderMonkey Debugger (and its cleanup)

We’ve made major improvements to JavaScript debugging in Firefox DevTools over the past two years. Developer feedback has informed and validated our work on performance, source maps, stepping reliability, pretty printing, and more types of breakpoints. Thank you. If you haven’t tried Firefox for debugging modern JavaScript in a while, now is the time.

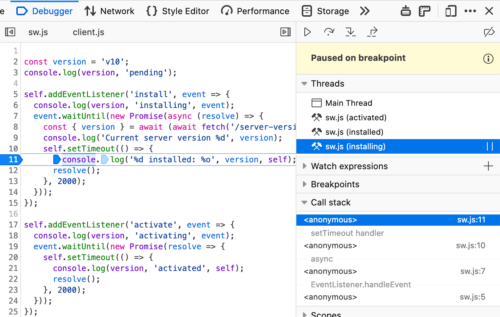

Many of the aforementioned efforts focused on the Debugger frontend (written in React and Redux). We were able to make steady progress. The integration with SpiderMonkey, Firefox’s JavaScript engine, was where work went more slowly. To tackle larger features like proper asynchronous call stacks (available now in DevEdition), we needed to do a major cleanup. Here’s how we did that.

Background: A Brief History of the JS Debugger

The JavaScript debugger in Firefox is based on the SpiderMonkey engine’s Debugger API. This API was added in 2011. Since then, it has survived the addition of four JIT compilers, the retirement of two of them, and the addition of a WebAssembly compiler. All that, without needing to make substantial changes to the API’s users. Debugger imposes a performance penalty only temporarily, while the developer is closely observing the debuggee’s execution. As soon as the developer looks away, the program can return to its optimized paths.

A few key decisions (some ours, others imposed by the situation) influenced the Debugger‘s implementation:

- For better or worse, it is a central tenet of Firefox’s architecture that JavaScript code of different privilege levels can share a single heap. Object edges and function calls cross privilege boundaries as needed. SpiderMonkey’s compartments ensure the necessary security checks get performed in this free-wheeling environment. The API must work seamlessly across compartment boundaries.

Debuggeris an intra-thread debugging API: events in the debuggee are handled on the same thread that triggered them. This keeps the implementation free of threading concerns, but invites other sorts of complications.Debuggers must interact naturally with garbage collection. If an object won’t be missed, it should be possible for the garbage collector to recycle it, whether it’s aDebugger, a debuggee, or otherwise.- A

Debuggershould observe only activity that occurs within the scope of a given set of JavaScript global objects (say, a window or a sandbox). It should have no effect on activity elsewhere in the browser. But it should also be possible for multipleDebuggers to observe the same global, without too much interference.

Garbage Collection

People usually explain garbage collectors by saying that they recycle objects that are “unreachable”, but this is not quite correct. For example, suppose we write:

fetch("https://www.example.com/")

.then(res => {

res.body.getReader().closed.then(() => console.log("stream closed!"))

});

Once we’re done executing this statement, none of the objects it constructed are reachable by the rest of the program. Nonetheless, the WHATWG specification forbids the browser from garbage collecting everything and terminating the fetch. If it were to do so, the message would not be logged to the console, and the user would know the garbage collection had occurred.

Garbage collectors obey an interesting principle: an object may be recycled only if it never would be missed. That is, an object’s memory may be recycled only if doing so would have no observable effect on the program’s future execution—beyond, of course, making more memory available for further use.

The Principle in Action

Consider the following code:

// Create a new JavaScript global object, in its own compartment.

var global = newGlobal({ newCompartment: true });

// Create a new Debugger, and use its `onEnterFrame` hook to report function

// calls in `global`.

new Debugger(global).onEnterFrame = (frame) => {

if (frame.callee) {

console.log(`called function ${frame.callee.name}`);

}

};

global.eval(`

function f() { }

function g() { f(); }

g();

`);

When run in SpiderMonkey’s JavaScript shell (in which Debugger constructor and the newGlobal function are immediately available), this prints:

called function g

called function f

Just as in the fetch example, the new Debugger becomes unreachable by the program as soon as we are done setting its onEnterFrame hook. However, since all future function calls within the scope of global will produce console output, it would be incorrect for the garbage collector to remove the Debugger. Its absence would be observable as soon as global made a function call.

A similar line of reasoning applies for many other Debugger facilities. The onNewScript hook reports the introduction of new code into a debuggee global’s scope, whether by calling eval, loading a

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2020/03/future-proofing-firefoxs-javascript-debugger-implementation/

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Spotty privacy practices of popular period trackers |

We don’t think twice when it comes to using technology for convenience. That can include some seriously personal aspects of day-to-day life like menstruation and fertility tracking. For people who … Read more

The post Spotty privacy practices of popular period trackers appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/privacy-practices-period-trackers/

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: More privacy means more democracy |

The 2020 U.S. presidential election season is underway, and no matter your political lean, you want to know the facts. What do all of these politicians believe? How do their … Read more

The post More privacy means more democracy appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/more-privacy-means-more-democracy/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: curl 7.69.0 ssh++ and tls– |

There has been 56 days since the previous release. As always, download the latest version over at curl.haxx.se.

Perhaps the best news this time is the complete lack of any reported (or fixed) security issues?

Numbers

the 189th release

3 changes

56 days (total: 8,020)

123 bug fixes (total: 5,911)

233 commits (total: 25,357)

0 new public libcurl function (total: 82)

1 new curl_easy_setopt() option (total: 270)

1 new curl command line option (total: 230)

69 contributors, 39 new (total: 2,127)

32 authors, 15 new (total: 771)

0 security fixes (total: 93)

0 USD paid in Bug Bounties

Contributors

Let me first highlight these lovely facts about the community effort that lies behind this curl release!

During the 56 days it took us to produce this particular release, 69 persons contributed to what it is. 39 friends in this crowd were first-time contributors. That’s more than one newcomer every second day. Reporting bugs and providing code or documentation are the primary ways people contribute.

We landed commits authored by 32 individual humans, and out of those 15 were first-time authors! This means that we’ve maintained an average of well over 5 first-time authors per month for the last several years.

The making of curl is a team effort. And we have a huge team!

Changes

In this release cycle we finally removed all traces of support for PolarSSL in the TLS related code. This library doesn’t get updates anymore and has effectively been superseded by its sibling mbedTLS – which we already support since years back. There’s really no reason for anyone to hang on to PolarSSL anymore. Move over to a modern library. wolfSSL, mbedTLS and BearTLS are all similar in spirit and focus. curl now supports 13 different TLS libraries.

We added support for a command line option (--mail-rcpt-allowfails) as well as a libcurl option (CURLOPT_MAIL_RCPT_ALLLOWFAILS) that allows an application to tell libcurl that recipients are fine to fail, as long as at least one is fine. This makes it much easier for applications to send mails to a series of addresses, out of which perhaps a few will fail immediately.

We landed initial support for wolfSSH as a new SSH backend in curl for SFTP transfers.

My top-11 favorite bug-fixes

As usual we’ve landed over a hundred bug-fixes, where most are minor. Here are eleven of the fixes I think stand out a little:

SOCKS connects are now non-blocking

For a very long time we’ve had this outstanding issue that libcurl did the connection phase to SOCKS proxies in a blocking fashion. This of course had unfortunate side-effects if you do many parallel transfers and maybe use slow or remote SOCKS proxies as then each such connection would starve out the others for the duration of the connect handshake.

Now that’s history and libcurl performs SOCKS connection establishment totally non-blocking!

Improved alt-svc parsing

Turns out I had misunderstood the spec a little and the parser needed to be fixed to better deal with some of the real-world Alt-Svc: response headers out there! A fine side effect of more people trying out our early HTTP/3 support, as this is the first major use case of this header in the wild.

Atomic cookie and alt-svc file saves

When saving files to disk, libcurl would previously simply open the file, write all the contents to it and then close it. This caused issues for multi-threaded libcurl users that potentially could start to try to use the saved file before it was done saving, and thus would end up reading partial file. This concerns both cookie and alt-svc usage.

Starting now, libcurl will always save these files into a temporary file with a random suffix while writing data to them, and then when everything is complete, rename the file over to the actual and proper file name. This will make the saving (appear) atomic to all consumers of such files, even in multi-threaded scenarios.

HTTP/2 stream pauses

An application using libcurl to receive a download can tell libcurl to pause the transfer at any given moment. Typically this is used by applications that for some reason consumes the incoming data slowly or has to use small local buffer for it or similar. The transfer is then typically “unpaused” again within shortly and the data can continue flowing in.

When this kind of pause was done for a HTTP/2 stream over a connection that also had other streams going, libcurl previously didn’t actually pause the transfer for real but only “faked” it to the application and instead buffered the incoming data in memory.

In 7.69.0, libcurl will now actually pause HTTP/2 streams for real, even if it might still need to buffer up to a full HTTP/2 window size of data in memory. The HTTP/2 window size is now also reduced to 32MB to at least limit the worst case buffer need to that amount. We might need to come back to this in a future to provide better means for applications to deal with the window size and buffering requirements…

Increased Expect: threshold

Previously, libcurl would add the Expect: header if more than 1024 bytes were sent in the body. Now that limit is raised to 1 MB instead.

HTTP 417 treatment

A 417 HTTP response code from a server when curl has issued a request using the Expect: header means the request should be redone without that header. Starting now, curl does so!

openssl: make CURLINFO_CERTINFO not truncate x509v3 fields

This feature that lets an application extract certificate information from a site curl communicates to had an unfortunate truncating issue that made very long fields occasionally not get returned in full!

smtp: Support UTF-8 based host names

curl SMTP support is now improved when it comes to using IDN names in the URL host name and also in the email addresses provided to some of the SMTP related options and commands.

include: remove non-curl prefixed defines

The public libcurl include files now finally define or provide not a single symbol that isn’t correctly prefixed with either curl or libcurl (in various case versions). This was a cleanup that’s been postponed much too long but a move that should make the headers less likely to ever collide or cause problems in combination with other headers or projects. Keeping within one’s naming scope is important for a good ecosystem citizen.

curl_global_init polish

We made the function assume the EINTR flag by default and we moved away the IPv6 check. Two small parts in an ongoing work to eventually make it thread-safe.

CIFuzz and more Azure jobs

We bumped the number of CI jobs per commit significantly this release cycle, up from 61 to 72.

- CIFuzz is a great new addition which runs the commit/PR through the OSS-Fuzz fuzzers for a brief time to at verify that it doesn’t at least trigger a problem already then. For now we have that time limit set to 10 minutes.

- A lot of Marc H"orsken’s Windows builds have been moved over from his more or less custom buildbot setup over to Azure Pipelines.

Next?

File your pull requests. We welcome them!

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2020/03/04/curl-7-69-0-ssh-and-tls/

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Extension Spotlight: Worldwide Radio |

Before Oleksandr Popov had the idea to build a browser extension that could broadcast thousands of global radio stations, his initial motivation was as abstract as it was aspirational. “I … Read more

The post Extension Spotlight: Worldwide Radio appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/firefox-extension-worldwide-radio/

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Your 2020 election podcast playlist |

Every day online, we’re bombarded with messages from 2020 U.S. presidential candidates, their supporters, and their adversaries. Just how much does the internet impact our political views? Are online election … Read more

The post Your 2020 election podcast playlist appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/your-2020-election-podcast-playlist/

|

|

Wladimir Palant: PSA: jQuery is bad for the security of your project |

For some time I thought that jQuery was a thing of the past, only being used in old projects for legacy reasons. I mean, there are now so much better frameworks, why would anyone stick with jQuery and its numerous shortcomings? Then some colleagues told me that they weren’t aware of jQuery’s security downsides. And I recently discovered two big vulnerabilities in antivirus software 1 2 which existed partly due to excessive use of jQuery. So here is your official public service announcement: jQuery is bad for the security of your project.

By that I don’t mean that jQuery is inherently insecure. You can build a secure project on top of jQuery, if you are sufficiently aware of the potential issues and take care. However, the framework doesn’t make it easy. It’s not secure by default, it rather invites programming practices which are insecure. You have to constantly keep that in mind and correct for it. And if don’t pay attention just once you will end up with a security vulnerability.

Why is jQuery like that?

You have to remember that jQuery was conceived in 2006. Security of web applications was a far less understood topic, e.g. autoescaping in Django templates to prevent server-side XSS vulnerabilities only came up in 2007. Security of client-side JavaScript code was barely considered at all.

So it’s not surprising that security wasn’t a consideration for jQuery. Its initial goal was something entirely different: make writing JavaScript code easy despite different browsers behaving wildly differently. Internet Explorer 6 with its non-standard APIs was still prevalent, and Internet Explorer 7 with its very modest improvements wasn’t even released yet. jQuery provided a level of abstraction on top of browser-specific APIs with the promise that it would work anywhere.

Today you can write document.getElementById("my-element") and call it done. Back then you might have to fall back to document.all["my-element"]. So jQuery provided you with jQuery("#my-element"), a standardized way to access elements by selector. Creating new elements was also different depending on the browser, so jQuery gave you jQuery("

The danger of simple

You might have noticed a pattern above which affects many jQuery functions: the same function will perform different operations depending on the parameters it receives. You give it something and the function will figure out what you meant it to do. The jQuery() function will accept among other things a selector of the element to be located and HTML code of an element to be created. How does it decide which one of these fundamentally different operations to perform, with the parameter being a string both times? The initial logic was: if there is something looking like an HTML tag in the contents it must be HTML code, otherwise it’s a selector.

And there you have the issue: often websites want to find an element by selector but use untrusted data for parts of that selector. So attackers can inject HTML code into the selector and trick jQuery into substituting the safe “find element” operation by a dangerous “create a new element.” A side-effect of the latter would be execution of malicious JavaScript code, a typical client-side XSS vulnerability.

It took until jQuery 1.9 (released in 2013) for this issue to be addressed. In order to be interpreted as HTML code, a string has to start with < now. Given incompatible changes, it took websites years to migrate to safer jQuery versions. In particular, the Addons.Mozilla.Org website still had some vulnerabilities in 2015 going back to this 1 2.

The root issue that the same function performs both safe and dangerous operations remains part of jQuery however, likely due to backwards compatibility constrains. It can still cause issues even now. Attackers would have to manipulate the start of a selector which is less likely, but it is still something that application developers have to keep in mind (and they almost never do). This danger prompted me to advise disabling jQuery.parseHTML some years ago.

Downloads, insecure by default

You may be familiar with secure by default as a concept. For an application framework this would mean that all framework functionality is safe by default and dangerous functionality has to be enabled in obvious ways. For example, React will not process HTML code at execution time unless you use a property named dangerouslySetInnerHTML. As we’ve already seen, jQuery does not make it obvious that you might be handling HTML code in dangerous ways.

It doesn’t stop there however. For example, jQuery provides the function jQuery.ajax() which is supposed to simplify sending web requests. At the time of writing, neither the documentation for this function, nor documentation for the shorthands jQuery.get() and jQuery.post() showed any warning about the functionality being dangerous. And yet it is, as the developers of Avast Secure Browser had to learn the hard way.

The issue is how jQuery.ajax() deals with server responses. If you don’t set a value for dataType, the default behavior is to guess how the response should be treated. And jQuery goes beyond the usual safe options resulting in parsing XML or JSON data. It also offers parsing the response as HTML code (potentially running JavaScript code as a side-effect) or executing it as JavaScript code directly. The choice is made based on the MIME type provided by the server.

So if you use jQuery.ajax() or any of the functions building on it, the default behavior requires you to trust the download source to 100%. Downloading from an untrusted source is only safe if you set dataType parameter explicitly to xml or json. Are developers of jQuery-based applications aware of this? Hardly, given how the issue isn’t even highlighted in the documentation.

Harmful coding patterns

So maybe jQuery developers could change the APIs a bit, improve documentation and all will be good again? Unfortunately not, the problem goes deeper than that. Remember how jQuery makes it really simple to turn HTML code into elements? Quite unsurprisingly, jQuery-based code tends to make heavy use of that functionality. On the other hand, modern frameworks recognized that people messing with HTML code directly is bad for security. React hides this functionality under a name that discourages usage, Vue.js at least discourages usage in the documentation.

Why is this core jQuery functionality problematic? Consider the following code which is quite typical for jQuery-based applications:

var html = ""

;

for (var i = 0; i < options.length; i++)

html += "" + options[i] + "";

html += "";

$(document.body).append(html);

Is this code safe? Depends on whether the contents of the options array are trusted. If they are not, attackers could inject HTML code into it which will result in malicious JavaScript code being executed as a side-effect. So this is a potential XSS vulnerability.

What’s the correct way of doing this? I don’t think that the jQuery documentation ever mentions that. You would need an HTML escaping function, an essential piece of functionality that jQuery doesn’t provide for some reason. And you should probably apply it to all dynamic parts of your HTML code, just in case:

function escape(str)

{

return str.replace(/span>, "<").replace(/>/g, ">")

.replace(/"/g, """).replace(/&/g, "&");

}

var html = ""

;

for (var i = 0; i < options.length; i++)

html += "" + escape(options[i]) + "";

html += "";

$(document.body).append(html);

And you really have to do this consistently. If you forget a single escape() call you might introduce a vulnerability. If you omit a escape() code because the data is presumably safe you create a maintenance burden – now anybody changing this code (including yourself) has to remember that this data is supposed to be safe. So they have to keep it safe, and if not they have to remember changing this piece of code. And that’s already assuming that your initial evaluation of the data being safe was correct.

Any system which relies on imperfect human beings to always make perfect choices to stay secure is bound to fail at some point. McAfee Webadvisor is merely the latest example where jQuery encouraged this problematic coding approach which failed spectacularly. That’s not how it should work.

What are the alternatives?

Luckily, we no longer need jQuery to paint over browser differences. We don’t need jQuery to do downloads, regular XMLHttpRequest works just as well (actually better in some respects) and is secure. And if that’s too verbose, browser support for the Fetch API is looking great.

So the question is mostly: what’s an easy way to create dynamic user interfaces? We could use a templating engine like Handlebars for example. While the result will be HTML code again, untrusted data will be escaped automatically. So things are inherently safe as long as you stay away from the “tripple-stash” syntax. In fact, a vulnerability I once found was due to the developer using tripple-stash consistently and unnecessarily – don’t do that.

But you could take one more step and switch to a fully-featured framework like React or Vue.js. While these run on HTML templates as well, the template parsing happens when the application is compiled. No HTML code is being parsed at execution time, so it’s impossible to create HTML elements which weren’t supposed to be there.

There is an added security bonus here: event handlers are specified within the template and will always connect to the right elements. Even if attackers manage to create similar elements (like I did to exploit McAfee Webadvisor vulnerability), it wouldn’t trick the application into adding functionality to these.

https://palant.de/2020/03/02/psa-jquery-is-bad-for-the-security-of-your-project/

|

|

Jan-Erik Rediger: Two-year Moziversary |

Woops, looks like I missed my Two Year Moziversary! 2 years ago, in March 2018, I joined Mozilla as a Firefox Telemetry Engineer. Last year I blogged about what happened in my first year.

One year later I am still in the same team, but other things changed. Our team grew (hello Bea & Mike!), and shrank (bye Georg!), lots of other changes at Mozilla happened as well.

However one thing stayed during the whole year: Glean.

Culminating in the very first Glean-written-in-Rust release, but not slowing down after,

the Glean project is changing how we do telemetry in Mozilla products.

Glean is now being used in multiple products across mobile and desktop operating systems (Firefox Preview, Lockwise for Android, Lockwise for iOS, Project FOG). We've seen over 2000 commits on that project, published 16 releases and posted 14 This Week in Glean blogposts.

This year will be focused on maintaining Glean, building new capabailities and bringing more of Glean back into Firefox on Desktop. I am also looking forward to speak more about Rust and how we use it to build and maintain cross-platform libraries.

To the next year and beyond!

Thank you

Thanks to my team: :bea, :chutten, :Dexter, :mdboom & :travis!

Lots of my work involves collaborating with people outside my direct team, gathering feedback, taking in feature requests and triaging bug reports.

So thanks also to all the other people at Mozilla I work with.

|

|

The Firefox Frontier: Are you registered to vote? |

Left, right, or center. Blue, red, or green. Whatever your flavor, it’s your right to decide the direction of your community, state and country. The first step is to check … Read more

The post Are you registered to vote? appeared first on The Firefox Frontier.

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: curl ootw: –next |

(previously posted options of the week)

--next has the short option alternative -:. (Right, that’s dash colon as the short version!)

Working with multiple URLs

You can tell curl to send a string as a POST to a URL. And you can easily tell it to send that same data to three different URLs. Like this:

curl -d data URL1 URL2 URL2

… and you can easily ask curl to issue a HEAD request to two separate URLs, like this:

curl -I URL1 URL2

… and of course the easy, just GET four different URLs and send them all to stdout:

curl URL1 URL2 URL3 URL4

Doing many at once is beneficial

Of course you could also just invoke curl two, three or four times serially to accomplish the same thing. But if you do, you’d loose curl’s ability to use its DNS cache, its connection cache and TLS resumed sessions – as they’re all cached in memory. And if you wanted to use cookies from one transfer to the next, you’d have to store them on disk since curl can’t magically keep them in memory between separate command line invokes.

Sometimes you want to use several URLs to make curl perform better.

But what if you want to send different data in each of those three POSTs? Or what if you want to do both GET and POST requests in the same command line? --next is here for you!

--next is a separator!

Basically, --next resets the command line parser but lets curl keep all transfer related states and caches. I think it is easiest to explain with a set of examples.

Send a POST followed by a GET:

curl -d data URL1 --next URL2

Send one string to URL1 and another string to URL2, both as POST:

curl -d one URL1 --next -d another URL2

Send a GET, activate cookies and do a HEAD that then sends back matching cookies.

curl -b empty URL1 --next -I URL1

First upload a file with PUT, then download it again

curl -T file URL1 --next URL2

If you’re doing parallel transfers (with -Z), curl will do URLs in parallel only until the --next separator.

There’s no limit

As with most things curl, there’s no limit to the number of URLs you can specify on the command line and there’s no limit to the number of --next separators.

If your command line isn’t long enough to hold them all, write them in a file and point them out to curl with -K, --config.

|

|