Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

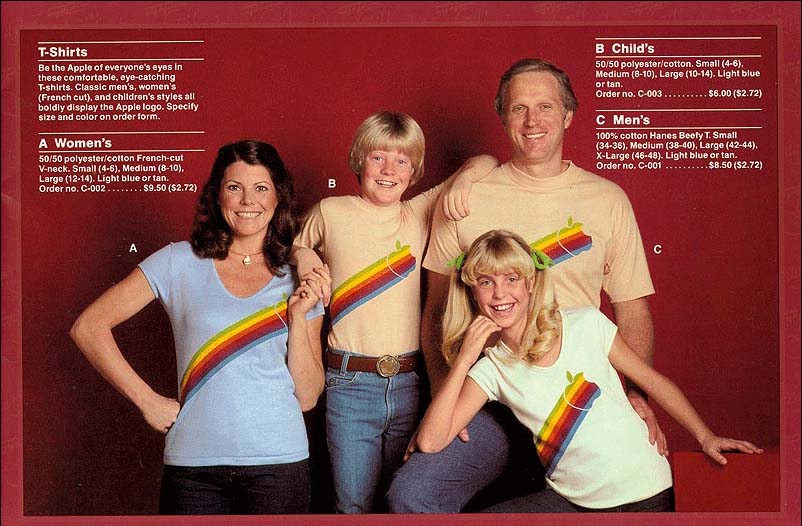

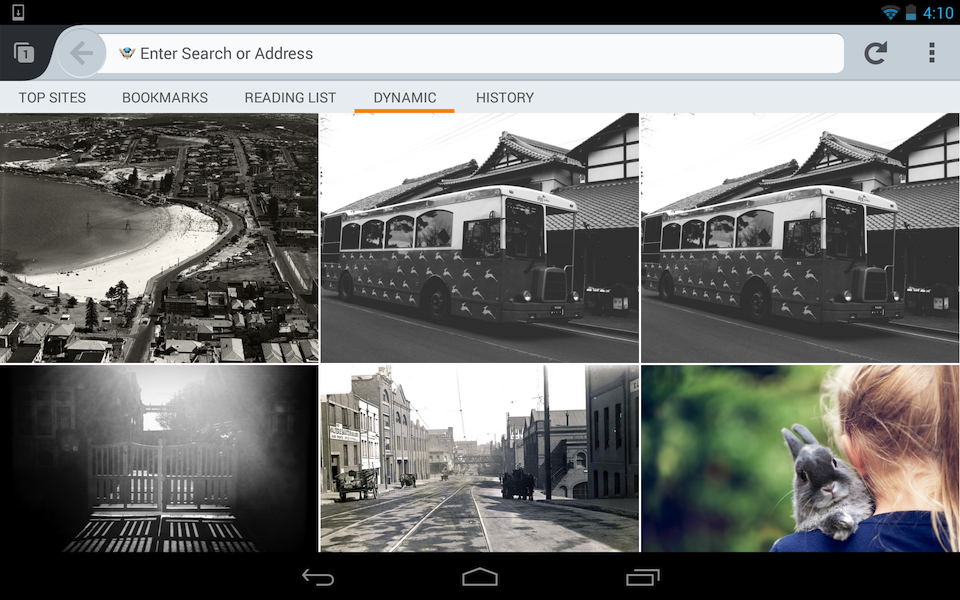

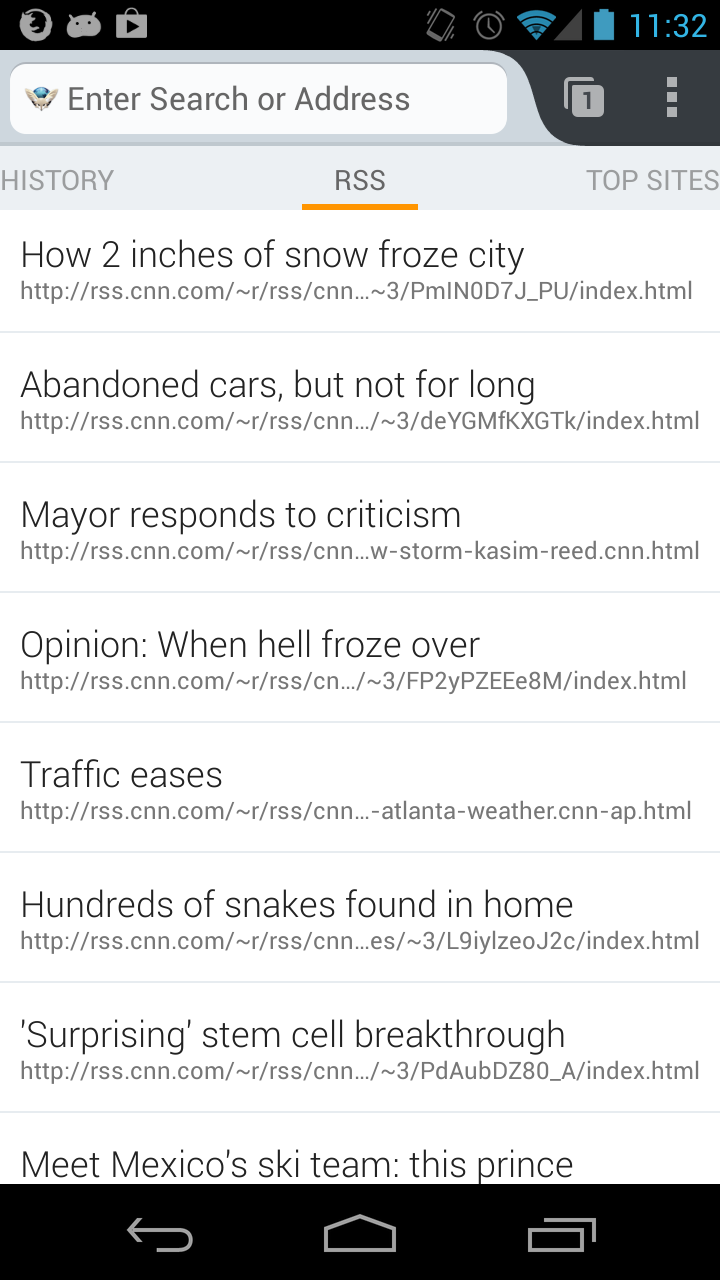

Margaret Leibovic: WIP: Home Page Customization in Firefox for Android |

In Firefox 26, we released a completely revamped version of the Firefox for Android Home screen, creating a centralized place to find all of your stuff. While this is certainly awesome, we’ve been working to make this new home screen customizable and extensible. Our goal is to give users control of what they see on their home screen, including interesting new content provided by add-ons. For the past two months, we’ve been making steady progress laying the ground work for this feature, but last week the team got together in San Francisco to bring all the pieces together for the first time.

Firefox for Android has a native Java UI that’s partially driven by JavaScript logic behind the scenes. To allow JavaScript add-ons to make their own home page panels, we came up with two sets of APIs for storing and displaying data:

- HomeProvider.jsm holds basic data storage APIs, which allow add-ons to save data to specific datasets.

- Home.jsm contains new APIs to add new panels to the home page, including specifying which kinds of views to make in these panels, and which datasets should back those views.

During the first half of our hack week, we agreed on a working first version of these APIs, and we hooked up our native Java UI to HomeProvider data stored from JS. After that, we started to dig into the bugs necessary to flesh out a first version of this feature.

- Chenxia recently landed a new page in settings to allow users to manage their home panels, and she has been working on a patch to allow them to install new panels from this settings page (bug 942878).

- Lucas has been working on a patch series to allow add-ons to auto-install new panels to about:home (bug 964375). He also has patches to add images to dynamic views using the Picasso image loading library (bug 963046).

- Sola (one of our awesome interns), added support for a galley view layout in dynamic panels (bug 942889).

- Josh (our other awesome intern), is working to support folder views in dynamic panels, similar to our built-in bookmarks panel (bug 942295), and he also added support for handling clicks on these dynamic views (bug 963721).

- Michael has been working on an RSS add-on to demo (and dogfood) these new APIs.

- I’ve also started exploring how add-ons will authenticate users (bug 942281), as well as ways to help them sync data in a battery/storage/network-friendly way (bug 964447).

Many of these patches are still waiting to land, so unfortunately there’s nothing to show in Nightly yet. But stay tuned, exciting things are coming soon!

|

|

Swarnava Sengupta: New Firefox Sync has landed in Firefox Nightly |

The new Firefox Sync has already landed in Firefox Nightly while the old Sync is also still operational for the most part.

This may sound confusing at first, but it is not really the case.

If you use the old Firefox Sync, then you probably wonder how to switch to the new version, and what impact not switching to the new version may have on the synchronization functionality.

The old sync works just fine for now for the most part. You can still synchronize all of your devices with each other without making any changes. What you cannot do anymore however is add new devices that you want synced as well.

In addition, Mozilla will support the old sync technology only for a limited amount of time before it will stop support for it.

It is still possible to use the old sync at that point, but only if you are using a community supported self-hosted solution as explained here.

Setting up the new Firefox Sync

If you are not using the old Firefox Sync, skip the following step. Before you can configure the new Firefox Sync on your system, you need to unlink all of your existing Sync devices.

You do so with a click on the settings button, selecting Options, and then the Sync tab. Click on unlink this device to discontinue the old Firefox Sync on the system.

To create a new Firefox Sync account, do the following.

- Click on the Settings button again and select Sign in to Sync.

- Or, load about:accounts directly in the browser's address bar.

- Click on the Get Started button displayed here.

- You are asked to create a Firefox account by entering your email address, selecting a password, and your year of birth.

- Here you can also check the "Choose what to sync" option to customize the data that gets synchronized by the browser.

- A verification link is sent to the email address. The email is verified when you load that link.

- If you have selected to customize the sync settings, you can do so on the next screen.

- Firefox Sync has been successfully set up after you hit the Start button.

It does mean that Firefox users need to create a Firefox Account to use Sync, and while other browsers handle this in the same way, Chrome Sync requires a Chrome account for example, some users may not like the idea of using an email address to create such an account.

A Firefox Account is also required to use the Firefox Marketplace. Mozilla has additional account-related ideas that it may implement at one point in time.

http://blog.swarnava.in/2014/02/new-firefox-sync-has-landed-in-firefox.html

|

|

Anthony Hughes: Firefox 26, A Restrospective in Quality (Part II) |

A few days ago a wrote a post detailing a qualitative analysis of Firefox 26 using statistics from Bugzilla. In it I talked about regressions and the volume speaking to a “potential failure, something that was missed, not accounted for, or unable to be tested either by the engineer or by QA”. I’d like to modify that a little by incorporating post-release regressions.

Certainly one would expect the volume of regressions in pre-release to increase as QA, Engineers, or volunteers find and report more regressions. I realize now that simply measuring the volume of regressions might not be a clear indication of quality or a breakdown in process. Perhaps I painted this a bit too broadly.

I’ve just retooled this metric to take a look at pre-release versus post-release regression volume. I think looking at regressions in this way is a bit more telling. After all, a pre-release regression is something we technically knew about before release whereas a post-release regression is something that became known after we released. A high volume of post-release regressions would therefore imply a lower quality release and an opportunity for us to improve.

Just as a reminder, here is the chart comparing all regressions from a few days ago:

Here is the new chart incorporating regressions found post-release:

As you can see the volume of post-release regressions is fairly significant. Perhaps unsurprisingly chemspills seem to correlate to periods of more post-release regressions. Speaking of Firefox 26 specifically, it continues a downward trend marking the fourth release with fewer post-release regressions and fewer regressions overall.

Anyway, that’s all I wanted to call out for this release. I will be back in six weeks to talk about how things shaped up for Firefox 27. I’m hoping we can continue to see improvements through iterating on our process and working closer with other teams.

|

|

Eric Shepherd: First five “paper cuts” of 2014 |

A recent initiative for the development of the Kuma software powering the Mozilla Developer Network (MDN) site is that we are going to be maintaining a list of the top five “paper cut” bugs that we’d like the dev team to find time to fix. These won’t have a schedule attached to them, and will only be worked on when other, priority items are fixed, but will each have a huge impact on the site’s usability, functionality, or simple friendliness.

During the MDN writing staff meeting (about which I’ll be blogging over the next few days), we pored over the long list of pending MDN bugs and selected the five we’d like to see the development team try to tackle as time allows.

- Fix the positioning of the save button and the revision comment edit box so they’re closer to each other, so that scrolling around to get at them isn’t necessary. These should always be available without having to scroll.

- Fix the “Clone this page” option so that it works again. It’s been broken for months.

- Implement subtree watching. The current page watching feature only watches the one page you’ve asked to watch, and we need to add the option to watch all of its subpages as well.

- When a page is reverted to a previous version, the cached rendered copy of the page isn’t rebuilt, which means that visitors to the page keep seeing the wrong version of the page. We need to fix this so that reverting also immediately rebuilds the page.

- When you visit a page that’s reached through a redirect, the page’s URL contains added query information that indicates where the redirect came from. This bloats the URL unnecessarily. This, as well as some display information about the redirect in-page, needs to be cleaned up.

I think you’ll agree that each time one of these is fixed, there will be celebratory riots in the streets!

http://www.bitstampede.com/2014/02/03/first-five-paper-cuts-of-2014/

|

|

David Burns: Updated BrowserMob Proxy Python Documentation |

After much neglect I have finally put some effort into writing some documentation for the BrowserMob Proxy Python bindings however I am sure that they can be a lot better!

To do this I am going to need your help! If there are specific pieces of information, or examples, that you would like in the documentation please either raise an issue or even better create a pull request with the information, or example, that you would like to see in the documentation.

http://www.theautomatedtester.co.uk/blog/2014/updated-browsermob-proxy-python-documentation.html

|

|

Tristan Nitot: I'm a Mozillian |

Today, in San Francisco, a Mozilla Monument is officially unveiled. I took pictures of it when I was in California a few weeks ago:

My contribution to Mozilla started 16 years ago, in January 1998, a few weeks before the Mozilla project was launched, and event that has changed my life in many ways. A colleague of mine (I'm looking at you, Barry!) asked me a couple of questions on email, and I'd like to share the answers publicly:

"Why are you a member of the Mozilla Community?"

I was a Netscape employee in Paris back in January 1998, and my job title was "Product PR manager". Trained as an engineer, my role was to explain to the media what this Internet thing was about. Best. Job. Ever. Then Netscape announced that due to competitive pressure, it was making its Web browser (Netscape Communicator 4.x at the time) free. This was easy to understand for most. But there was something else to be announced: its source code was going to be released in the open, for people to contribute to it, the Open Source way. Most people stopped understanding that sentence right when reading "source code". No kidding. Nobody had an idea what it meant. And for those who knew, "Open Source" did not ring a bell. It happened that I had some background in Open Source or, more precisely, Free Software. I had met with Richard Stallman in the past and was a long-time user of Emacs ten years earlier.

For many people around me at Netscape, often salespeople or marketing people, this Open Source/Free Software thing was nonsense: it was too technical to be understood and the bottom line was that... it did not contribute to the bottom line.

For me, it was the possibility to invent a revolutionary new future, to build a piece of the Internet, to create a new way to work, to help make the world a better place. It immediately fell in love. This love is still growing strong today.

"Name a fellow Mozillian who inspires you"

So many Mozillians inspire me. In November 2011 at Mozcamp Berlin, I gave a talk that started like this: "You are my heroes". I meant it back then and I still mean it today. So instead of giving one name, let me list a handful of people, even if the three of them will probably hate me for naming them:

- Peterv, my fellow co-founder of Mozilla Europe and long-time friend. His wisdom and calm are inspiring for me. Without him, I would never have started the Mozilla Europe adventure.

- Mitchell Baker, for her commitment to Mozilla (did you know Mitchell was fired from Netscape and remained for a long time at the helm of Mozilla as a volunteer?) This is just an example to her commitment.

- Debbie Cohen, for what she's doing with programs such as LEAD and TRIBE to Mozillians. This is transforming the organization and makes it a lot better. I don't think I've ever heard anything like this happening in other Open Source projects.

"How being a Mozillian has changed your life?"

My life would not be what is is today without Mozilla. I just can't imagine my life without Mozilla!

|

|

Melissa Romaine: Earning Bett(er) Badges |

Technology Will Save Us were there, running a very cool session on programming their DIY Gamer. On a sheet of paper filled with blank boxes, the maker first designed an avatar and its movements in response to different key combinations on a game console. Then, by doing some simple programming on a computer, the maker brought to life his/her video game.

Next to them, Webmaker ran a Thimble workshop, introducing HTML and CSS code through the "Keep Calm and…" starter make. A few days earlier, I met 4 very cool young makers at Lutthworth High in Leicestershire. These E-leaders were recruited to attract teachers and show them how to do some simple coding at Bett. We spent Monday afternoon making things on Thimble, exploring different variables to play with, and discovering what worked and what didn't in a short period of time. After doing some homework (teaching a family member or friend how to make something on Thimble), they were geared up and ready to work at Bett. And work they did! Alongside community Webmaker mentors, FuzzyFox, and myself the E-leaders brought teachers to the stand with their smiles, and walked them through designing their very own "Keep Calm and…" make. Some of the #Bett2014 makes are pretty creative!

For teachers looking to get ideas before delving into digital making, Stone Computers organized a stand where various educators could share their thoughts and tips on getting digital in the classroom. There was an impressive line-up over the 4 days, including Mozilla's Doug Belshaw and Tim Riches talking about the value of integrating badges, and how they're aligned with our Web Literacy Map. Doug's slide deck is here. I had the opportunity to share how coding could be used as a medium for creative expression, and how it doesn't have to be the content focus in any classroom. I encouraged teachers to get their classes involved in upcoming campaigns, like International Privacy Day on January 28th and celebrating the 25th birthday of the Web this year. My slides are here.

All of these activities were neatly tied together with badges -- in fact, participants were earning badges for every activity they completed! Digital Me and the Badge The UK teams were buzzing about issuing badges for achievements and talking to teachers about incorporating badges in school. It was beautiful to see everyone excited about the upcoming Badge Kit, and discussing how this could be relevant with their students. It'll be even more interesting to see how everyone integrates it into their systems.

http://londonlearnin.blogspot.com/2014/02/earning-better-badges.html

|

|

Jesse Ruderman: Fuzzers love assertions |

Fuzzers make things go wrong.

Assertions make sure we find out.

Assertions can improve code quality in many ways, but they truly shine when combined with fuzzing. Fuzzing is normally limited to finding obvious symptoms like crashes, because it's rare to be able to tell correct behavior from incorrect behavior when the input is generated randomly. Assertions expand the scope of fuzzing to include everything they check.

Assertions can even help find crash bugs: some bugs are relatively easy for fuzzers to trigger, but only lead to crashes when additional conditions are met. A well-placed assertion can let us know every time we trigger the bug.

Fuzzing JS and DOM has found about 4000 assertion bugs, including about 300 security bugs.

Asserting safe use of generic data structures

Assertions in widely-used data structures can find bugs in many callers.

- Array indices must be within bounds. This simple precondition assert in nsTArray has caught about 90 bugs.

- Hash tables must not be modified during enumeration. If the modification happened to resize the hash table, it would leave stack pointers dangling. This PLDHashTable assertion has caught over 50 bugs.

- Cached values should not be out of date. When a cache's

getmethod takes a key and a closure for computing values in the case of a cache miss, debug builds can check whether the cached values are still correct. This is effectively a form of differential testing that notices bugs in cache-invalidation logic.

Asserting module invariants

When an entire module must maintain an invariant, a single assertion can catch dozens of bugs.

- Compartment mismatches. When a JS object in one page's compartment references an object in another, it must do so through a wrappers that enforces security policies. Without these assertions, we would have missed over 25 violations of Firefox's script security model.

- Phases of layout. These assertions have strings like "Should be in an update while creating frames" and "reflowing in the middle of frame construction". More phase and nesting assertions are wanted, but sometimes special cases like plugins get in the way.

Making the frame arena safer

Gecko's CSS box objects, called "frames", are created and destroyed manually. They are allocated within an arena to reduce malloc overhead and fragmentation. The arena also made it possible to reduce the risk associated with manual memory management. A combination of assertions (in debug builds) and runtime mitigations (in all builds) mitigates dangling pointer bugs that involve frames.

- When the arena is destroyed, debug builds assert that all objects in the arena were also destroyed. Over 60 bugs have been caught by the assertion. About half of the bugs that trigger the assertion can lead to exploitable crashes, but without a specially crafted testcase, they will not crash at all.

- While the arena is still alive, deleted frames are overwritten with a special poison pattern. If any code uses a pointer from a deleted frame, the browser will segfault safely. This mitigation, called frame poisoning, has prevented dozens of bugs from being exploitable.

- Writing over the poison trips another assertion. This assertion is actually more prone to catch hardware errors than software bugs, so it has been modified to help distinguish between the two.

Requests for Gecko developers

Please add assertions, especially when:

- A bug would be a security hole

- Crashing is not guaranteed

- Many callers must fulfill a precondition

- Complex, extensive code must maintain an invariant

Also consider:

- Ensure assertions in third-party libraries are enabled in debug builds of Firefox.

- Fix bugs requesting new assertions.

- Fix my assertion bugs to allow my fuzzers to find more.

http://www.squarefree.com/2014/02/03/fuzzers-love-assertions/

|

|

Lloyd Hilaiel: Leaving Mozilla |

My first day at Mozilla was August 16th 2010, my last will be February 14th 2014.

My first day as a Mozillian was either in November 2004, or it might have been around January 2008. I will not have a last day as a Mozillian.

|

|

Soledad Penades: What have I been working on? (2014/01) |

January is over, what have I done with it?

Well, to start with I’ve been working with the fantastic people from Firefox DevTools. We’re preparing a new feature for the App Manager and I’m really thrilled to be a part of this. I’m not going to disclose what it is yet until I have something to show (it’s my way to make you all download a Nightly build, tee hee), but I believe it’s going to be GREAT.

Then I’ve also been lending my brain to other projects. First, localForage, our library for storing data using the same interface from localStorage, but asynchronously and with better performance (by using IndexedDB or WebSQL if available). Or just falling back to localStorage otherwise (sad face, sad face).

The other project I’m involved with is chatspaces, “a snazzy chat app”. I’ve done some (yet unfinished) work with implementing push notifications using Simple Push, and I’m also working on outputting better GIFs (i.e. smaller but with same perceived quality). If you’re up for a slightly bumpy ride, you can try out chatspaces today.

“Generating better GIFs” means that I’m spending quite a bit of time in Animated_GIF, a library for creating animated GIFs in the browser. I implemented a couple of features like dithering and custom palettes past week and I’m pretty happy with the results you can get. I still have some more work to do before it’s a totally awesome library from README to code to examples, but it’s already used in somewhat popular places like chat.meatspac.es which you might have heard about ;-)

And I’ve also written an article for Mozilla Hacks. If you liked my previous article on unprefixed Web Audio code, I think you might like this one too. It should be published some time soon (fingers crossed).

There are more things that I’ve been doing this month like attending LNUG’s meetup, helping people with their Firefox OS apps, improving documentation for X-Tag, and finding+filing a bunch of bugs… all of which make me terribly happy as I feel like I’m making an impact. Yay! :-)

http://soledadpenades.com/2014/02/02/what-have-i-been-working-on-201401/

|

|

Christian Heilmann: Why “just use Adblock” should never be a professional answer |

Ahh, ads. The turd in the punchbowl of the internet party. Slow, annoying things full of dark interaction patterns and security issues. Good thing they are only for the gullible and not really our issue as we are clever; we use browsers that blocked popups for years and we use an ad blocker!

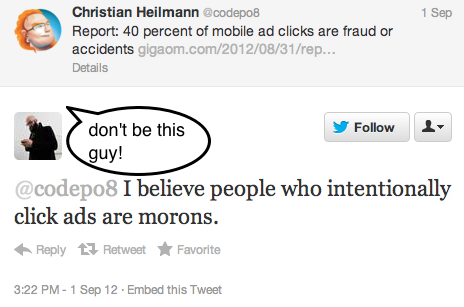

Hang on a second. Whether we like it or not, ads are what makes the current internet work. They are what ensures the “free” we crave and benefit from, and if you dig deep enough you will find that nobody working in web development or design is not in one way or another paid by income stemming from ad sales on the web. Thus, us pretending that ads are for other people is sheer arrogance. I’ve had discussions about this a few times and so far the pinnacle to me still was an answer I got on Twitter to posting an article that 40 percent of mobile ad clicks are fraud or accidents:

I believe people who intentionally click ads are morons

Don’t get me wrong: ads as a whole are terrible. In many cases they have the grace of a drunk guy kicking you in the shin before asking you to buy him a beer. They are very much to blame for our users being conditioned to things behaving in weird ways on the web, thus opening the door for the bad guys to phish and clickjack them. Ads may also be the thing that drives many of our users to preferring apps instead. Which is kind of ironic as an app in many cases is a mixture of a bit of highly catered functionality wrapped in an interactive ad.

We’re blocking our own future

So what does that make us? Not the intelligent people who know how to game the system, but people not owning the platform we work for and are reliant on. As people in the know, it should be our job to ensure ads we publish or include in our project are not counterproductive to the optimisation efforts we put into our work. We also should have a stake in the kind of ads that are being displayed, making sure they don’t soil the messages we try to convey with our content.

A lack of empathy and a lie to ourselves

This is uncomfortable, it is extra work and it feels like we are depriving ourselves of an expert shortcut. The problem with blocking ads ourselves is though that we are not experiencing what our end users experience. We get the first class treatment of the web with comfortable computers and less interruptions whilst our users are stuck in a low cost carrier where they get asked every few seconds if they don’t want to buy something and pay extra if they forgot to bring the printout of their ticket.

By blocking all the ads and advocating for “clever web users” to do the same we perpetuate a model of only the most aggressive and horrible ads to get through. We treat each ad the same, the “find sexy singles in your IP range” and the actual useful ones: we just block them all. Yes, I’ve had some deals by clicking an ad. Yes, I found things I really use and am happy to have now by clicking an ad. I could have never done that with an ad blocker. What it does though is cut into the views of ads and thus force ad companies to play dirty to get the figures they are used to and use to negotiate payments to the people who display their ads. In essence, we are creating the terrible ads we hate as we don’t allow the good ones to even show up. It’s like stopping people swearing by not allowing anyone to speak. Or trying to block adult content by filtering for the word “sex”.

The current ad model is too comfortable and can be gamed

You could say that people who expect everything to be free don’t deserve better. This would hold water if the paid experiences of the web without ads were better or even available. In many cases, they are not. You can not pay for Facebook to get rid of ads. Many providers are so comfortable in the horrible model of “plaster everything with ads and create as much traffic as possible” that trying a subscription model instead bears too much danger and extra effort in comparison.

A sign of this is the horrible viral bullshit world we live in right now. Creators of original content are not the ones who make the most money with it; instead it is the ones who put it in “this kid did one weird trick, the result will amaze you” headlined posts with lots of ads and social media sharing buttons. This is killing the web. We allowed the most important invention for publishing since the printing press brought literacy to the masses to become a glossy lifestyle magazine that spies on its readers.

It should be up to us to show better ways, to create more engaging interfaces, to play with the technology and break conventions. It is sad to see that all we have to show for about 16 years of web innovation is that we keep some parts of our designs blank where other people can paste in ads using code we don’t even know or trust or care to understand. This isn’t innovative; this is lazy.

There’s more to come here and some great stuff brewing in Mozilla Labs. It is time to be grown-up about this: ads happen, let’s make them worth-while for everyone involved.

http://christianheilmann.com/2014/02/02/why-just-use-adblock-should-never-be-a-professional-answer/

|

|

Nick Cameron: Changing roles |

I'm pretty sad to be leaving rendering behind. It has been immense fun hacking on this stuff for the last couple of years. I have learnt a tremendous amount and got to work with some awesome people. I'm going to really miss working with my friends from the rendering teams.

However, I am super excited about working on Rust. It is a really exciting project and fits my background in many ways (ownership, in a real language!). I'm also looking forward to working with the research team and the Rust community. They've done some excellent work already and have been really helpful getting me started learning Rust over the past month or so.

http://featherweightmusings.blogspot.com/2014/02/changing-roles.html

|

|

Selena Deckelmann: PyLadies Meeting notes from “Negotiating the job market: a panel discussion” |

Flora Worley organized a fantastic PyLadies PDX meeting called “Negotiating the job market: a panel discussion“.

The meeting was organized in three parts:

- Experiences (good, bad and ugly) from four women who entered the software industry in the last 1-2 years.

- Managing expectations and setting boundaries from three people, two recent entrants into the industry, and me.

- Negotiating the application/interview/offers process (which we turned into a group discussion, led by one panelist)

We kicked things off by asking people to get into groups of four and talk to each other about why they came and what they were hoping to get out of the meeting.

Some of the comments from the meeting and feedback after included:

- On what was good prep for interviewing: Attending PyLadies and Python User Group meetups to learn new skills, hear about what modules and techniques people are using. (from Amy Boyle, a local developer)

- Attending PyLadies helped fill in gaps in knowledge useful as a working programmer, even after having a CS degree.

- “I love being a Pylady, and if it weren’t for this community, I honestly don’t know that I would have continued learning to code.”

Below are my notes from the first panel, anonymized and edited a bit.

How did you find your first job in the industry and know it was the right place for you?

- I knew a founder of the company from college

- Knew someone and they invited me to apply. Wrote a great cover letter and got an interview even though they thought I didn’t have the skills for the exact job I applied for.

- Got the job by going to talks and staying and talking to the speakers.

- Decided I was more interested in data than my major! Looked around and found a company that was doing a lot with data.

At what point do you say you “know” a programming language?

- I shy away from saying I “know” something — seems presumptuous to say that the same way it seems weird to say “I’m a writer.” If you’re getting paid to do a thing, though, then you get to call yourself the “thinger”. Coworker has been asking me for help with python and I know the answers to his questions so…

- Finding ways to help others with things is a good way to boost your confidence.

- Once I give a talk about something, I have to say I know how to do it because people will come to me for help. It’s a way to force yourself to cram, find out what you know and really don’t know. On my resume I don’t say “I know” — I say “I have experience with XYZ; I have managed to learn these things to get the job done.” Most technical interviews ask more general questions.. not exact syntax of a language.

- Interviews seem to be trying to figure out if you can learn whatever it happens to be that they need you for at the job.

- We have to support many languages. So many languages at the same time can get overwhelming.

- I don’t say I’m an IOS programmer, but I help people write and improve their IOS code all the time.

What was your interview like?

- Shared projects I made. We just went through my github repo. Tell me about this project, what did you do, what did you use.

- Was interviewed over Skype

- Interviewed with 4 people in a marathon. None of those interviews were super technical.

- The interviews seemed to be gauging whether you would be able to just talk about whatever comes up.

- They asked me about a lot of command line skills and brought lots of people in from different parts of the company.

- The interview had me sit down with a program — there’s a bug in this program solve it. What I learned is what matters is the process of how you work on bugs — and being able to communicate that while you’re doing it, not that you actually fix it.

- Most valued skill is resilience rather than a technical background. You can learn, compensate, fill in gaps. Need willingness to learn, capacity to be frustrated/despair and just move on. People don’t want to hear you freaking out, just want you to do it. Even if it takes you a long time.

Were there classes or resources that prepared you for interviewing?

- Go out and make something for yourself. Nothing better than finding a thing you want to make, and then making it. Going back to old code, really fulfilling to see progress and wanting to make old code better. You have something to share!

- Coming to meetings like PyLadies and the Python User Groups. I took some CS classes, but there was lots that I missed. You don’t realize how much you don’t know! Get to meetups to hear about what others are using, what is current in the field. Having a sense of with what the latest stuff is, what are good blogs, best practices, helps out. (seconded by another panelist)

- Very helpful to go to PyLadies and talk with people around my same experience level. In conversation, people would explain stuff to you in a way that made sense, not just a bunch of jargon.

- Learning that ecosystem and what tools people use is huge. Helps you figure out what a job entails and what do you need to know to build it.

- For most of the stuff you’ll build, you’re going to use other libraries. It helps having experience mushing things together. Iterate on it. Every little thing you learn, you’ll find ways of improving stuff.

What if your coding style is really different than other people’s? How do you handle that?

- Get good at giving constructive feedback

- “days of spaghetti code is behind us” at the mercy of other people’s crappy code — tech companies deal with this a lot less.

- Don’t be afraid to say “no idea what this function ” learned a lot about better code by reviewing a lot of code

What kinds of positions can you get? And where do you want to go?

- Really overwhelming to learn everything I needed to know to support product. It’s an all guys team, learned to love them all, took on a mother role.

- Teaching stuff all guy team can be intimidating, but most of the guys I work with are college educated CS guys, me having no CS background was intimidating until I realized I knew and could learn this stuff as quickly as they could. No CS didn’t matter.

- I’m doing tech support, wish I could do more coding. It’s a mixed bag doig support, you learn a lot about system. Found that management wanted everyone to level up in tech support and not go to other parts of the company. I’ve had to come to terms with managers trying to keep me in that role. Need to see how long they expect you to stay in that role before you can move on — ask up front.

- Had similar experience — resistance to moving from tech support into other roles. Most people in support are looking to move into another role. Make sure you’re on the same page with manager rather than be surprised by it later.

- On working with guys: my communication style was not really effective when I started. Sometimes had customers that said “can I talk to tech support?” “can I talk to an engineer?”. Had to learn how to be kind of cocky — “This is how this works.” If I was wrong, I was wrong, and had to fix it but that was much more effective at communicating with customers and coworkers.

- Had to learn that nothing wrong with asking for help. Saves a lot of time.

- Everything takes me longer than I think it will. Triple your estimates!

- I needed to learn its ok to ask questions, ask questions confidently rather than despair of never being a programmer. We all tell ourselves crap like: “i’m just generally stupid and can’t learn anything” or “can’t learn javascript in a day, so clearly i’m an idiot”. But turning that around is important for yourself.

- Be dilligent in the way you ask questions: 1) first google it, stack overflow, check reference book; 2) write out the question fully (rubber ducking) — articulate the problem fully and you might solve it for yourself — what did i expect, what happened, what else can i expect….

- I’ve had people say to me: “I don’t know why pyladies needs to exist.” I said: “I think its nice its a safe place where that you can articulate your questions without fear.” I don’t know what to do about it other than say that.

- Men might be made clear to you that they believe we are post-sexist, post-racist. If you have too many of those people around, find a new job.

- “you need to be careful about where you are” when expressing opinions about feminism.

- Be open and honest, and they tend to understand.

- Sometimes it may be the case you have to figure out if an opinion is being expressed because of privilege or malice. If privilege, it can be worked on.

- Try to internalizing confidence. Tell yourself: “I know how to program” more. Once I really believed that, my programming got better. Because I know I will solve the problem I’m working on!

Do you find that as a woman you communicate differently and you are interpreted differently?

- Here’s an example: when someone says: “Can you pass the salt?” One person might respond by thinking, “I understand you’re being polite and phrasing that request as a question rather than a command. Sure, here’s the salt!” Or another person might respond with, “I could pass the salt to you. Is that actually what you want me to do?” Pretty different communication styles.

- Try to be flexible and ride out conflict.

- I question myself a lot — did i interrupt too many times, was i too aggressive. I worry I am too aggressive.

- Be yourself. Take time to figure out if you are happy or not.

- Try to compromise and avoid “truth bombs” where you “explain how the world is”. Take conversations case by case and try not to take it personally.

- If it gets to be too much, get out of there!

|

|

Priyanka Nag: Campus Konnect II |

The event was rightly named and it was organized exactly a year after the version I. This time, the venue was chosen to be Techno India college at Rajarhat, Kolkata.

This event was meant to open the doors of the Open Source world to the first year computer students of this renowned technical college. The event was planned and organized by Sayak Sarkar, presently a Mozilla Reps Council member, with the help of Srijib Roy,a local Mozillian from the college.

Kaustav Das Modak, a Mozilla Representative, and I were invited as guest speakers for the event. The event start unfortunately got delayed by an hour due to some technical issues faced by the organizers. Instead of 10am (IST), we began at 11am. I took the stage to begin the day with an introduction to Open Source followed by a Mozilla introduction. I touched a bit upon what are the different Mozilla products and current projects being supported by Mozilla. I also spoke a little about how one could get involved with Mozilla and start their open source contribution.

After an introduction session, I handed it over to Kaustav who introduced the MDN project to the participants. After Kaustav, Vineel Reddy Pindi, an ex-council member and one of the oldest (I only mean in terms of experience and absolutely not in terms of age) Mozillians from India, took the stage and spoke about the Firefox Student Ambassador program.

After all the introduction sessions got over we decided to turn the passive listers to active coders and thus divided the crowd into two groups and began parallel hands-on sessions on MDN Code Sprint and MDN Documentation Sprint. As always, Kaustav led the code sprint and I took care of the Documentation sprint. This time, when we had a proper planning done on our end to not let anything go wrong, the Internet did fail us. The connection was so poor that both these sessions turned out to be mostly one way talk sessions where we just explained the participants how to do stuff instead of getting a change of doing something for real. With all the internet issues getting pretty common in most events now, the Mozilla India community is brainstorming on how best we could deal with the situation.

Post lunch, it was a Firefox OS app-building session led by Sayak and Kaustav. Sayak gave a detailed introduction about Firefox OS and Kaustav carefully tutored the participants to build some apps in a very simple and easy way.

Now that the Indian technical crowd is partially aware of the new mobile operating system in market, their enthusiasm to learn more and get more details about it makes our Firefox OS sessions a great hit always. We get fired with a lot of interested questions.

Though we didn't have too many swags this time, we tried giving away the little things we had, to the crowd, in the best possible manner. The deserving participants did depart with some Mozilla stuff which they could proudly show off to their fellow mates later ;)

Take aways from this event:

1) MDN is highly Internet dependent. We need to find ways to make sure not to trust on the event venue's internet facilities and the organizer's promises. Need some kind of backup plan from our end.

2) Need to think if we could implement a simple username-password authentication method for MDN instead of depending on Persona.

In the absence of stable Internet, Persona keeps us from getting even user-profiles created.

Other blogposts of this event:

http://priyankaivy.blogspot.com/2014/02/campus-konnect-ii.html

|

|

Shane Tomlinson: v0.49 Release of the Persona WordPress Plugin |

Today I released v0.49 of the Persona WordPress plugin. This release fixes an issue with Strict Standards warnings on the admin page.

Thank you Jason D. Moss for the fix!

https://shanetomlinson.com/2014/persona-browserid-wordpress-plugin-49/

|

|

Joshua Cranmer: Why email is hard, part 5: mail headers |

Back in my first post, Ludovic kindly posted, in a comment, a link to a talk of someone else's email rant. And the best place to start this post is with a quote from that talk: "If you want to see an email programmer's face turn red, ask him about CFWS." CFWS is an acronym that stands for "comments and folded whitespace," and I can attest that the mere mention of CFWS is enough for me to start ranting. Comments in email headers are spans of text wrapped in parentheses, and the folding of whitespace refers to the ability to continue headers on multiple lines by inserting a newline before (but not in lieu of) a space.

I'll start by pointing out that there is little advantage to adding in free-form data to headers which are not going to be manually read in the vast majority of cases. In practice, I have seen comments used for only three headers on a reliable basis. One of these is the Date header, where a human-readable name of the timezone is sometimes included. The other two are the Received and Authentication-Results headers, where some debugging aids are thrown in. There would be no great loss in omitting any of this information; if information is really important, appending an X- header with that information is still a viable option (that's where most spam filtration notes get added, for example).

For this feature of questionable utility in the first place, the impact it has on parsing message headers is enormous. RFC 822 is specified in a manner that is familiar to anyone who reads language specifications: there is a low-level lexical scanning phase which feeds tokens into a secondary parsing phase. Like programming languages, comments and white space are semantically meaningless [1]. Unlike programming languages, however, comments can be nested—and therefore lexing an email header is not regular [2]. The problems of folding (a necessary evil thanks to the line length limit I keep complaining about) pale in comparison to comments, but it's extra complexity that makes machine-readability more difficult.

Fortunately, RFC 2822 made a drastic change to the specification that greatly limited where CFWS could be inserted into headers. For example, in the Date header, comments are allowed only following the timezone offset (and whitespace in a few specific places); in addressing headers, CFWS is not allowed within the email address itself [3]. One unanticipated downside is that it makes reading the other RFCs that specify mail headers more difficult: any version that predates RFC 2822 uses the syntax assumptions of RFC 822 (in particular, CFWS may occur between any listed tokens), whereas RFC 2822 and its descendants all explicitly enumerate where CFWS may occur.

Beyond the issues with CFWS, though, syntax is still problematic. The separation of distinct lexing and parsing phases means that you almost see what may be a hint of uniformity which turns out to be an ephemeral illusion. For example, the header parameters define in RFC 2045 for Content-Type and Content-Disposition set a tradition of ;-separated param=value attributes, which has been picked up by, say, the DKIM-Signature or Authentication-Results headers. Except a close look indicates that Authenticatin-Results allows two param=value pairs between semicolons. Another side effect was pointed out in my second post: you can't turn a generic 8-bit header into a 7-bit compatible header, since you can't tell without knowing the syntax of the header which parts can be specified as 2047 encoded-words and which ones can't.

There's more to headers than their syntax, though. Email headers are structured as a somewhat-unordered list of headers; this genericity gives rise to a very large number of headers, and that's just the list of official headers. There are unofficial headers whose use is generally agreed upon, such as X-Face, X-No-Archive, or X-Priority; other unofficial headers are used for internal tracking such as Mailman's X-BeenThere or Mozilla's X-Mozilla-Status headers. Choosing how to semantically interpret these headers (or even which headers to interpret!) can therefore be extremely daunting.

Some of the headers are specified in ways that would seem surprising to most users. For example, the venerable From header can represent anywhere between 0 mailboxes [4] to an arbitrarily large number—but most clients assume that only one exists. It's also worth noting that the Sender header is (if present) a better indication of message origin as far as tracing is concerned [5], but its relative rarity likely results in filtering applications not taking it into account. The suite of Resent-* headers also experiences similar issues.

Another impact of email headers is the degree to which they can be trusted. RFC 5322 gives some nice-sounding platitudes to how headers are supposed to be defined, but many of those interpretations turn out to be difficult to verify in practice. For example, Message-IDs are supposed to be globally unique, but they turn out to be extremely lousy UUIDs for emails on a local system, even if you allow for minor differences like adding trace headers [6].

More serious are the spam, phishing, etc. messages that lie as much as possible so as to be seen by end-users. Assuming that a message is hostile, the only header that can be actually guaranteed to be correct is the first Received header, which is added by the final user's mailserver [7]. Every other header, including the Date and From headers most notably, can be a complete and total lie. There's no real way to authenticate the headers or hide them from snoopers—this has critical consequences for both spam detection and email security.

There's more I could say on this topic (especially CFWS), but I don't think it's worth dwelling on. This is more of a preparatory post for the next entry in the series than a full compilation of complaints. Speaking of my next post, I don't think I'll be able to keep up my entirely-unintentional rate of posting one entry this series a month. I've exhausted the topics in email that I am intimately familiar with and thus have to move on to the ones I'm only familiar with.

[1] Some people attempt to be to zealous in following RFCs and ignore the distinction between syntax and semantics, as I complained about in part 4 when discussing the syntax of email addresses.

[2] I mean this in the theoretical sense of the definition. The proof that balanced parentheses is not a regular language is a standard exercise in use of the pumping lemma.

[3] Unless domain literals are involved. But domain literals are their own special category.

[4] Strictly speaking, the 0 value is intended to be used only when the email has been downgraded and the email address cannot be downgraded. Whether or not these will actually occur in practice is an unresolved question.

[5] Semantically speaking, Sender is the person who typed the message up and actually sent it out. From is the person who dictated the message. If the two headers would be the same, then Sender is omitted.

[6] Take a message that's cross-posted to two mailing lists. Each mailing list will generate copies of the message which end up being submitted back into the mail system and will typically avoid touching the Message-ID.

[7] Well, this assumes you trust your email provider. However, your email provider can do far worse to your messages than lie about the Received header…

http://quetzalcoatal.blogspot.com/2014/01/why-email-is-hard-part-5-mail-headers.html

|

|

Asa Dotzler: Firefox OS Happenings: week ending 2014-01-31 |

In the last week, at least 96 Mozillians fixed about 200 bugs and features tracked in Product:Firefox OS and OS:Gonk.

These are a few of those that caught my eye:

[Rocketbar][meta] Get rocketbar patches landed in master This is a significant part of the Haida Firefox OS UX update that’s happening right now. Rocket Bar is the system-wide search and addressing feature that lots of other Haida UX is built around. Very exciting stuff.

B2G Wifi: Support Wifi Direct gives us the DOM API and related implementation for Wi-FI Direct in Firefox OS. Wi-Fi Direct, earlier called Wi-Fi P2P, is used to easily connect devices with each other without requiring a wireless access point.

We got a couple more good tablet fixes:

[Flatfish] make Context menu not fill fullscreen

[Flatfish] Add pathmap to support Bluez on android 4.2.2

A few nice usability wins:

[B2G][Settings] Developer settings are too hard to access

[Search] Add ‘Install’ text before Marketplace Title

Provide a way to fetch the message threads in reverse order

[Browser] It’s not possible to move the cursor to the last character in the URL bar

And here’s a sampling of the performance and memory improvements.

Rewrite net worker in C++

[1.3] Launch latency of SMS app needs to be improved

Reading objects from datastore has serious performance and memory consumption problems

[b2g] convert all vorbis files to opus to improve memory usage

Bluetooth leaks every blob

We’re also getting closer to the launch of the Firefox OS Tablet Contribution Program. Stay tuned to this site and hacks.mozilla.org for updates and the application form. Once again, it’d be useful for you to have your Mozillians profile already filled out and a Bugzilla account established.

http://asadotzler.com/2014/01/31/firefox-os-happenings-week-ending-2014-01-31/

|

|

Anthony Hughes: Firefox 26, A Retrospective in Quality |

[Edit: @ttaubert informed me the charts weren't loading so I've uploaded new images instead of linking directly to my document]

The release of Firefox 27 is imminently upon us, next week will mark the end of life for Firefox 26. As such I thought it’d be a good time to look back on Firefox 26 from a Quality Assurance (QA) perspective. It’s kind of hard to measure the impact QA has on a per release basis and whether our strategies are working. Currently, the best data source we have to go on is statistics from Bugzilla. It may not be a foolproof but I don’t think that necessarily devalues the assumptions I’m about to make; particularly when put in the context of data going back to Firefox 5.

Before I begin, let me state that this data is not indicative of any one team’s successes or failures. In large part this data is limited to the scope of bugs flagged with various values of the status-firefox26 flag. This means that there are a large amount of bugs that are not being counted (not every bug has the flag accurately set or set at all) and the flag itself is not necessarily indicative of any one product. For example, this flag could be applied to Desktop, Android, Metro, or some combination with no way easy way to statistically separate the two. Of course one could with some more detailed Bugzilla querying and reporting, but I’ve personally not yet reached a point where I’m able or willing to dig that deep.

Unconfirmed Bugs

Unconfirmed bugs are an indication of our ability to deal with the steady flow of incoming bug reports. For the most part these bugs are reported from our users (trusted Bugzilla accounts are automatically bumped up to NEW). The goal is to be able to get down to 0 UNCONFIRMED bugs before we release a product.

What this data tells us is that we’ve held pretty steady over the months, in spite of the ever increasing volume, but things have slipped somewhat in Firefox 26. In raw terms, Firefox 26 was released with 412 of the 785 reported bugs being confirmed. The net result is a 52% confirmation rate of new bug reports.

However, if we look at these numbers in the historical context it tells us that we’ve slipped by 10% confirmation rate in Firefox 26 while the volume of incoming bugs has increased by 64%. A part of me sees this as acceptable but a large part of me sees a huge opportunity for improvement.

The lesson here is that we need to put more focus on ensuring day to day attention is paid to incoming bugs, particularly since many of them could end up being serious regressions.

Regressions

Regressions are those bugs which are a direct result of some other bug being resolved. Usually this is caused by an unforeseen consequence of a particular code change. Regressions are not always immediately known and can exist in hiding until a third-party (hardware, software, plug-in, website, etc) makes a change that exposes a Firefox regression. These bugs tend to be harder to investigate as we need to track down the fix which ultimately caused the regression. If we’re lucky the offending change was a recent one as we’ll have builds at our disposal. However, in rare cases there are regressions that go far enough back that we don’t have the builds needed to test. This makes it a much more involved process as we have to begin bisecting changesets and rebuilding Firefox.

The number of regressions speaks to a potential failure, something that was missed, not accounted for, or unable to be tested either by the engineer or by QA. In a perfect world a patch would be tested taking into account all potential edge cases. This is just not feasible in reality due to the time and resources it would take to cover all known edge cases; and that’s to say nothing of the unknown edge cases. But that’s how open source works: we release software we think is ready, users report issues, and we fix them as fast and as through as we reasonably can.

In the case of Firefox 26 we’ve seen a continued trend of a reduction in known regressions. I think this is due to QA taking a more focused approach to feature testing and bug verifications. Starting with Firefox 24 we brought on a third QA release driver (the person responsible for coordinating testing of and ultimately signing-off on a release) and shifted toward a more surgical approach to bug testing. In other words we are trying to spend more time doing deeper and exploratory testing of bug fixes which are more risky. We are also continuing to hone our processes and work closer with developers and release managers. I think these efforts are paying off.

The numbers certainly seem to support this theory. Firefox 26 saw a reduction of regressions by 20% over Firefox 25, 25% over Firefox 24, and 57% better than Firefox 17 (our worst release for regressions).

Stability

Stability bugs are a reflection of how frequently our users are encountering crashes. In bugzilla these are indicated using the crash keyword. The most serious crashes are given the topcrash designation. The more crash bugs we ship in a particular release does not necessarily translate for more crashes per user, but it is indicative of more scenarios under which a user may crash. Many of these bugs are considered a subset of the regression bugs discussed earlier as these mostly come about by changes we have made or that a third-party has exposed.

In Firefox 26 we again see a downward trend in the number of crash bugs known to affect the release. I believe this speaks to the success of educating more people in the skills necessary to participate in reviewing the data in crash-stats dashboard, converting that into bugs, and getting the necessary testing done so developers can fix the issues. Before Firefox 24 was on the train the desktop QA really only had one or two people doing day to day triage of the dashboards and crash bugs. Now we have four people looking at the data and escalating bug reports on a daily basis.

The numbers above indicate that Firefox 26 saw 12% less crash bugs that Firefox 25, 41% less than Firefox 24, and 59% less than Firefox 15, our most unstable release.

Reopened

Reopened bugs are those bugs which developers have landed a fix for but the issue was proven not to have been resolved in testing. These bugs are a little bit different than regressions in that the core functionality the patch was meant to address still remains at issue (resulting in the bug being reopened), whereas a regression is typically indicative of an unforeseen edge case or user experience (resulting in a new bug being filed to block the parent bug).

That said, a high volume of reopened bugs is not necessarily an indication of poor QA; in fact it could mean the exact opposite. You might expect there to be a higher volume of reopened bugs if QA was doing their due diligence and found many bugs needing follow up work. However, this could also be an indication of feature work (and by consequence a release) that is of higher risk to regression.

As you can see with Firefox 26 we’re still pretty high in terms of the number of reopened bugs. We’re only 5% better than Firefox 23, our worst release in terms of reopened bugs. I believe this to be a side-effect of us doing more focused feature testing as indicated earlier. However it could also be indicative of problems somewhere else in the chain. I think it warrants looking at more closely and is something I will be raising in future discussions with my peers.

Uplifts vs Landings

Landings are those changes which land on mozilla-central (our development branch) and ride the trains up to release following the 6-week cadence. Uplifts are those fixes which are deemed either important enough or low enough risk that it warrants releasing the fix earlier. In these cases the fix is landed on the mozilla-aurora and/or mozilla-beta branches. In discussions I had last year with my peers I raised concerns about the volume of uplifts happening and the lack of transparency in the selection criteria. Since then QA has been working closer with Release Management to address these concerns.

I don’t yet have a complete picture to compare Firefox 26 to a broad set of historical data (I’ve only plotted data back to Firefox 24 so far). However, I think the data I’ve collected so far shows that Firefox 26 seemed far more “controlled” than previous releases. For one, the volume of uplifts to Beta was 29% less than Firefox 25 and there were 42% less uplifts across the entire Firefox 26 cycle compared to Firefox 25. It was also good to see that uplifts trailed off significantly as we moved through the Aurora cycle into Beta.

However, this does show a recent history of crash-landings (landing a crash late in a cycle) around the Nightly -> Aurora merge. The problem there is that something that lands on the last day of a Nightly cycle does not get the benefit of Nightly user feedback, nor does it get much, if any, time for QA to verify the fix before it is uplifted. This is something else I believe needs to be mitigated in the future if we are to move to higher quality releases.

Tracked Bugs

The final metric I’d like to share with you today is purely to showcase the volume of bugs. In particular how much the volume of bugs we deal with on a release-by-release basis has grown significantly over time. Again, I preface these numbers with the fact that these are only those bugs which have a status flag set. There are likely thousands of bugs that are not counted here because they don’t have a status flag set. A part of the reason for that is because the process for tracking bugs is not always strictly followed; this is particularly true as we go farther back in history.

As you can see above, the trend of ever increasing bug volume continues. Firefox 26 saw a 21% increase in tracked bugs over Firefox 25, and a 183% increase since we started tracking this data.

Firefox 26 In Retrospective

So there we have it. I think Firefox 26 was an incremental success over it’s predecessors. In spite of an ever increasing volume of bugs to triage we shipped less regressions and less crashes than previous releases. This is not just a QA success but is also a success borne of other teams like development and release management. It speaks to the success of implementing smarter strategies and stronger collaboration. We still have a lot of room to improve, in particular focusing more on incoming bugs, dealing with crash landings in a responsible way, and investigating the root cause of bugs that are reopened.

If we continue to identify problems, have open discussions, and make small iterative changes, I’m confident that we’ll be able to look back on 2014 as a year of success.

I will be back in six weeks to report on Firefox 27.

|

|

Wil Clouser: Splitting AMO and the Marketplace |

Years ago someone asked me what the fastest way to stand up an App Marketplace was. After considering that we already had several Add-on Types in AMO I replied that it would be to create another Add-on Type for apps, use the AMO infrastructure as a foundation for logins/reviews/etc. and do whatever minor visual tweaks were needed. This was a pretty quick solution but the plan evolved and “minor visual tweaks” turned into “major visual changes” and soon a completely different interface. Fast forward a few years and we have two separate sites (addons.mozilla.org and marketplace.firefox.com) running out of the same code repository but with different code. Much of the code is crudely separated (apps/ vs mkt/), but there are also many shared files, libraries, and utilities, both front and backend. The two sites run on the same servers but employ separate settings files.

There has been talk about combining the two sites so that the Firefox Marketplace was the one stop shop for all our apps/add-ons/themes/etc. but there was reluctance to move down that path due to the different user expectations and interfaces – for example, getting an app for your phone is a lot different flow than putting a theme on Firefox. While the debate has simmered with no great options the consequences of inaction continue to grow. Today’s world:

- Automated unit tests which take far longer than necessary to run because they run for both sites.

- Frustration for developers who change code in one area and affect a completely different site.

- Confusion for any new employees or contributors as they struggle to set up the site (despite our decent documentation).

- A one-size-fits-all infrastructure approach with no ability to optimize for the very different sites (API/service based vs standard MVC)

The best way to relieve the stress points above is complete separation of addons.mozilla.org and marketplace.firefox.com. Read the full (evolving) proposal. Feedback welcomed.

http://micropipes.com/blog/2014/01/31/splitting-amo-and-the-marketplace/

|

|

Ben Hearsum: This week in Mozilla RelEng – January 31st, 2014 |

Completed work (resolution is ‘FIXED’):

- Balrog: Backend

- setup sentry for balrog stage/prod

- balrog should notify when a release is added (or modified?) by a human

- Balrog: Frontend

- Buildduty

- Integration Trees closed, high number/time backlog of pending jobs

- upload a new talos.zip to pick up all the fixes

- B2G emulator build failure on try | OSError: [Errno 20] Not a directory: ‘.repo’

- General Automation

- Use spot instances for try builds

- Create hg share directory for gaia-central for test slaves

- add python packages to mozharness

- web-platform-tests mozharness script doesn’t set TBPL status correctly

- b2g 1.3t branch support

- Please schedule Android 4 reftests on all trunk trees and make them ride the trains

- Add public IPs to EC2 instances

- Increase mozpool request time

- Merge Fullflash and flash scripts together so it’s less confusing for people that are just onboarding to the project to flash releng builds

- Run ‘npm install’ as a separate step in the gaia-integration tests

- Increase how often the vcs sync runs on git.m.o

- Periodic PGO and non-unified builds shouldn’t be running again on pushes that already have them

- Schedule b2g desktop reftest-sanity on all trunk branches

- Allow AWS build slaves to access s3 buckets

- Schedule gaia-unit tests on all trunk trees

- Switch update server for Buri from OTA to FOTA by using the solution seen in bug 935059

- Start generating an additional build daily for Buri at 8am in Taipei’s timezone

- switch routing to ftp-ssl to use public internet

- Loan Requests

- Other

- Platform Support

- Build and deploy binutils 2.23.1 for testing

- New Windows build slaves fail in NSS on branches below trunk

- Increase mozpoolclient timeout for creating a new request

- Install Flash for Robocop tests

- install sox command to linux and linux64 hardware machines

- Release Automation

- Serve updates for MetroFirefox on beta channel

- Request notification of events affecting release timelines

- Releases

- Thunderbird 27.0b1 for Windows is not downloadable

- do a staging release of Firefox and Fennec 28.0b1

- tracking bug for build and release of Thunderbird 27.0b1

- Releases: Custom Builds

- Tools

- Add cppunittests as option in TryChooser

- slaveapi’s reboot action shouldn’t create a bug for a slave unless it was unable to reboot it

- Mark bugs as resolved where known in the buildduty report

- Add loan requests section to the buildduty report

- File slave bugs automatically for known failure cases

- upgrade boto in aws-ve on cruncher

- switch slave rebooter to use production slaveapi

- Buildbot improvement indices

- slaveapi filed a bunch of “unreachable” slave bugs for slaves that aren’t down now

- Create a ‘reftest’ alias for ‘reftest-1' and ‘reftest-2' linux-android unittest suites

In progress work (unresolved and not assigned to nobody):

- Balrog: Backend

- Balrog shouldn’t serve updates to older builds

- send cef events to syslog’s local4

- balrog should return empty snippets instead of 500s

- Buildduty

- Re-purpose mw32-ix-slave##, linux-ix-slave##, linux64-ix-slave##, bld-linux64-ix-05[1-3], mw32-ix-ref and linux-ix-ref as b-2008-ix-#### (rev2) machines

- Linux64 opt builds failing: make/compile step

- All trees closed due to timeouts as usw2 slaves download or clone

- General Automation

- Need automatic hsts preload list updates on any branches based on Gecko 18 and later

- mozilla-central should contain a pointer to the revision of all external B2G repos, not just gaia

- Intermittent “BaseException: Failed to connect to SUT Agent and retrieve the device root.”

- limit pvtbuilds uploads

- Provide B2G Emulator builds for Darwin x86

- Get existing metrofx talos tests running on release/project branches

- Run reftests on B2G Desktop builds

- Rooting analysis mozconfig should be in the tree

- gaia-ui tests need to dump a stack when the process crashes

- generate “flatfish” builds for B2G

- Compression for blobber

- Run desktop mochitests-browser-chrome on Ubuntu

- Make gecko and gaia archives from device builds publicly available

- Run win64 unit tests at bootup on tst-w64-ec2-xxx fork

- Remove ‘update_files’ logic from B2G unittest mozharness scripts

- Please add non-unified builds to mozilla-central

- Schedule gaia-ui-tests on cedar against emulator builds

- Tracking bug for 3-feb-2014 migration work

- keep buildbot master twistd logs longer

- Add ‘latest’ directory for mozilla-central TBPL b2g builds

- Run unittests on Win64 builds

- b2g builds failing with AttributeError: ‘list’ object has no attribute ‘values’ | caught OS error 2: No such file or directory while running ['./gonk-misc/add-revision.py', '-o', 'sources.xml', '--force', '.repo/manifest.xml']

- Land initial iteration of mozharness for web-platform-tests

- submit release builds to balrog automatically

- Split up mochitest-bc on desktop into ~30minute chunks

- [Tracking bug] automation support for B2G v1.3.0

- Run jit-tests from test package

- Loan Requests

- Need linux64 test slave to debug 959752

- Loan felipe an AWS unit test machine

- Slave tst-linux64-ec2 or talos-r3-fed for :marshall_law

- loan request for graydon [Ubuntu 64]

- I need 32 && 64 bit ubuntu test slaves setup just like the ones that report to tbpl

- Slave loan request for a tst-linux64-ec2 machine

- Need a slave for bug 818968

- Please assign a Linux32 test machine to me

- Other

- Upgrade ASan Clang in Q1

- [tracking] infrastructure improvements

- s/m1.large/m3.large/

- stage NFS volume about to run out of space

- s/m1.medium/m3.medium/

- [tracking] move services from cruncher to production

- Platform Support

- Build and deploy a patched gcc 4.7.3

- Please test new Virtual Audio Cable package on each Windows test machine

- try -u all does not trigger Android x86 S4

- s/m3.xlarge/c3.xlarge/

- Determine number of iX machines to request for 2014

- Upgrade Valgrind on build machines to 3.9.0

- Migrate mozilla-release and comm-release to win64-rev2

- Create a Windows-native alternate to msys rm.exe to avoid common problems deleting files

- Release Automation

- Releases

- tracking bug for build and release of Firefox 24.3.0 ESR

- figure out strategy for custom build support under Metro

- Releases: Custom Builds

- Partner repack changes for web.de, gmx, and mail.com (Firefox 27)

- Update Bing favicon to match current branding for partner builds and add-ons

- move inactive partner builds out of the build process

- Repos and Hooks

- Add a hook to detect changesets with wrong file metadata

- Implement a string checker hook on mozilla-aurora,mozilla-beta and mozilla-release repos to refuse string changes without specific approval

- Tools

- Create a Comprehensive Slave Loan tool

- New tooltool deployment

- cut over build/* repos to the new vcs-sync system

- Integrate slaveapi into slave heath

- Create report to allow determine if we have enough machine to handle the load (not from developer’s POV)

- tracker for all pending releng nagios work

- slaveapi still files IT bugs for some slaves that aren’t actually down

- [tracking] Implement a comprehensive slave health tool

- Standardize on single quotes in slave health

- # of constructors no longer being measured correctly

- Move js into libs as much as possible

http://hearsum.ca/blog/this-week-in-mozilla-releng-january-31st-2014/

|

|