-Музыка

- That is a big pee pee. OR: `Have you ever seen the rain?`

- Слушали: 34 Комментарии: 0

- MATCHISH, OR LADIES DO NOT GO THAT FAR

- Слушали: 29 Комментарии: 0

- THE SEVEN STRING GUITAR OR THERE WILL BE DANCING TONIGHT

- Слушали: 68 Комментарии: 0

- CAT`N`COOK, AN OLD RUSSIAN DON RIVER COSSACK LULLABY

- Слушали: 43 Комментарии: 0

-Поиск по дневнику

-Подписка по e-mail

-Статистика

A GREEN KITTY`S LIBRARY - UNA BIBLIOTECA DE UN GATITO VERDE |

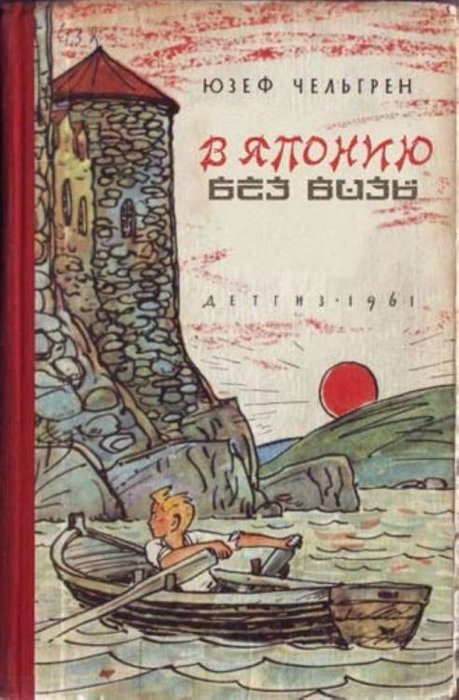

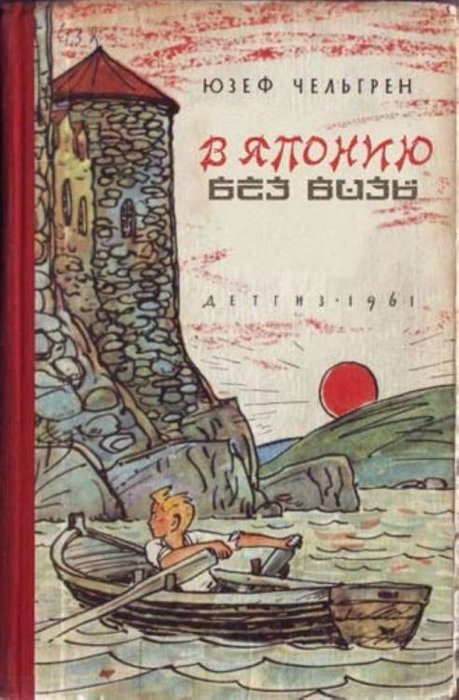

TO JAPAN WITHOUT A VISA - A JAPÓN SIN UNA VISA

Józef Czelgren. Manual for the Russian Teenagers from the series `Do it yourself!`: `How to get to Japan without a Visa`. Moscow, The Kid-Print Publishing House, 1961

MONGOLIA

By Feodor Swarowski/Por Feodor Swarowski

1.

japanese combat robots

have attacked Beijing.

all the Chinese are dead.

but due to a system failure

they spare no efforts

to ignore a kid.

robots japoneses de combate

han atacado Pekín.

todos los chinos están muertos.

pero debido a una falla del sistema

no escatiman esfuerzos

para ignorar a una niña.

2.

the grass is pushing up asphalt

on deserted Tian`anmen square.

flowers are as far as the eye can see.

electric elephants are roaming about streets.

their riders, the robots,

are all ill.

no more energy.

they need acid to be charged.

no more acid! why?

it has passed

the fifth year

since the start of the genocide.

la hierba está empujando hacia arriba el asfalto

en la plaza desierta de Tian`anmen.

las flores están tan lejos como el ojo puede ver.

elefantes eléctricos están deambulando por las calles.

sus jinetes, los robots,

están todos enfermos.

pas de más energía

necesitan ácido para ser cargado.

¡Pas plus más ácido! ¿Por qué?

ha pasado

el quinto año

desde el comienzo del genocidio.

3.

japanese businessman`s daughter Aiko

lives on the top of a hill

in the ruins of an old house.

outside is a view of the city.

a prison is at the foot of the hill.

she waits for none.

she’s 12, she’s alone every inch.

her only companions are

her torn teddy-bear, dog stuffed with rice.

other plastic fauna without paws and eyes.

food concentrates to expire soon.

there’s only a dozen of boxes

of the spoiled wine.

hija de un empresario japonés Aiko

vive en la cima de una colina

en las ruinas de una casa vieja.

afuera hay una vista de la ciudad.

una prisión está al pie de la colina.

ella no espera a ninguno.

ella tiene 12 años, está sola cada centímetro.

sus únicos compañeros son

su oso de peluche roto, perro relleno de arroz.

otra fauna plástica sin patas y ojos.

los concentrados de alimentos para caducar pronto.

solo hay una docena de cajas

del vino agrio.

4.

in search of a rat for dinner

once she entered the prison`s vault.

darkness and fear!

suddenly she heard someone called

en busca de una rata para la cena

una vez que ella vino debajo los arcos de la prisión.

oscuridad y miedo!

de repente oyó a alguien llamado

`who`s there?`

`girl, girl!

come here, please, try.

I am so alone

I am ill, so on

the demolished cities are still in my eyes`.

`¿quién está allí?`

`niña, niña!

Ven aquí, por favor, inténtalo.

estoy tan solo

Estoy enfermo,

las ciudades demolidas todavía están en mis ojos`.

5.

a boiler in the old house

concealed a replicant.

a robot who`s a human`s replica

was dying of

a heart attack.

una caldera en la casa vieja

ocultó un replicante.

un robot que es una réplica humana

estaba muriendo de

un infarto.

his cardiac muscle made of special fibre

grew weak.

the servoengine gonna stop inside of him.

su músculo cardíaco hecho de fibra especial

se debilitó

la servoingeniería se detendrá dentro de él.

my name is Ryuichi CI 9

I need acid badly

and solar energy.

gimme acid! some acid!

and free me - lemme outside!

mi nombre es Ryuichi CI 9

Realmente necesito ácido

Y energía solar.

¡Dame ácido! ¡Un poco de ácido!

¡Y líbrame, llévame afuera!

6.

Aiko was startled.

that robot

destroyed people.

but he just lay and watched her,

he looked like no enemy, after all.

not like a killer

or like a rogue.

never mind!

thought Aiko.

I am alone, life is mine.

she returned to the cellar

and brought back a glass of wine.

acid in wine helped the robot.

he could stand up,

come out to the streets

and breathe all right.

Aiko se sobresaltó.

ese robot

destruyó la gente.

pero él se quedó allí y la miró.

parecía que no enemigo, después de todo,

no un asesino

o un sinvergüenza.

¡no importa!

pensó Aiko.

Estoy solo, la vida es mía.

ella regresó a la bodega

y trajo una copa de vino.

el ácido en el vino ayudó al robot.

él podría ponerse de pie,

salir a la calle

y respira normalmente

7.

`but to survive all the way

I need to pump

sulfuric and hydrochloric acid in my empty

vessels. badly!

they say, there`s a state of Mongolia in the North

people use there machines and electric light

there might be acid for robots,

confectionery for children and for the adult.`

`do you remember what are sweets, Aiko?`

`no, I don`t remember that staff.`

`pero para recuperar completamente

es necesario bombear ácidos sulfúrico

y clorhídrico a mis vasos. ¡gravemente!

dicen, hay un estado de Mongolia en el norte

la gente usa allí máquinas y luz eléctrica

podría haber ácido para los robots,

dulces para niños y adultos.

`¿Recuerdas qué son los dulces, Aiko? `

`no, no recuerdo esas cosas!

8.

`why to stay all life in the destroyed house?`

decided Aiko.

`time flies.

life promises no changes.

better to dry out several rats,

take wine,

toys

and go

in search of acid and sweets.

may

the robot

atone for his sins

as a fellow traveller of a human being.

if I am tired

then, by the way, he`ll have to carry me!`

'¿por qué quedarse toda la vida en la casa destruida?'

decidió Aiko.

`el tiempo vuela.

la vida no promete cambios.

mejor secar varias ratas,

tomar vino,

juguetes

y ve

en busca de ácido y dulces

deja que el robot

expiar sus pecados

como un compañero de viaje de un ser humano.

si estoy cansado

entonces, por cierto, ¡él tendrá que llevarme!

9.

Aiko thought that `war was fine` as

the whole country was green.

only woods and villages

and cities.

no people – just silence,

water

and torn wires.

only wind,

only

the grass and wind

in the steppe

at nights Ryichi lit the campfires

and said

`while I`m on duty,

you go to bed.`

Aiko pensó que "la guerra estaba bien" como

todo el país era verde.

solo bosques y aldeas

y ciudades

no hay gente, solo silencio,

agua

y cables rotos.

solo viento,

solamente

la hierba y el viento

en la estepa

en las noches, Ryichi encendió las fogatas

y dijo

`mientras estoy de servicio,

te vas a la cama.

10.

they walked ten months to the west,

two months somewhere to the left,

then to the east.

Ryuichi grew faint under a weight.

wine ran out.

he was totally creased.

they lost their way,

Mongolia was faraway.

Aiko got tired

but no longer Ryuichi could carry again

her

in his arms as a babe.

caminaron diez meses hacia el oeste,

dos meses en algún lugar a la izquierda,

luego hacia el este.

Ryuichi se debilitó bajo un peso.

el vino se acabó.

él estaba totalmente exhausto.

perdieron su camino,

Mongolia era lejana.

Aiko se cansó

pero Ryuichi no podía ya llevarlа

su

en sus brazos como un bebé.

11.

once

after waking up in the morning

Aiko

was about

to cry out `Ah!`

wild horsemen noticed them

in the short,

dry grass,

soon caught them up to grasp.

they poped the robot twice

(all went dark before his eyes)

then took them to the city

to lock them behind bars.

una vez que

después de despertarse en la mañana

Aiko casi gritaba ¡Ah!

jinetes salvajes los han notado

pronto en la hierba seca,

y los atrapó para apoderarse.

golpean al robot dos veces

(todo se oscureció ante sus ojos)

luego los llevó a la ciudad

para encerrarlos entre rejas.

12.

this was `Mongolians`

but not Mongolians indeed

no plants

no factories

no acid

no sweets

no power stations

they walked almost bare

every second one professed cannibalism!

esto fue `mongoles`

pero no los mongoles de hecho

sin plantas

sin fábricas

sin ácido

sin dulces

sin estaciones de energía

caminaban casi desnudos

¡cada segundo profesaba canibalismo!

13.

Aiko and Ryuichi

spent ten days, kidnapped,

underground

in expectation of being eaten up.

`Ryuichi, what will be with us? we`re lost!

those people must be wrong Mongols,

not the people we searched for

you know, I`m not afraid,

but I feel emptiness inside

I wish we could fly away

to find out something quite different. ah?

The replicant answered,

`Aiko, there is more to it than meets the eye!

there must have been reason

I fell down

into the vault from above

and had no acid

to later meet you, just fancy!

Aiko y Ryuichi

pasó diez días, secuestrado,

subterráneo

en espera de ser comido.

`Ryuichi, ¿qué pasará con nosotros? estamos perdidos!

esas personas deben no real estar mongoles,

no las personas que buscamos

ya sabes, no tengo miedo,

pero siento vacío dentro

Ojalá pudiéramos irnos volando

para descubrir algo bastante diferente, ah?

El replicante respondió:

`¡Aiko, no es un accidente!

debe haber habido razón

Me caí

en debajo los arcos desde arriba

y no tenía ácido

para luego conocerte, ¡Imagine juste!

true Mongolia must be

placed somewhere else.

Mongolia is the wind and fields

we walked across not once.

and empty houses, you see?

the buildings in bushes

(their floors covered with dust).

and dry flowers, and their seeds!

la verdadera Mongolia debe ser

colocado en otro lugar.

Mongolia es el viento y los campos

donde cruzamos no una vez.

y casas vacías, ¿entiendes?

los edificios en arbustos

(sus pisos cubiertos de polvo).

y flores secas y sus semillas!

Mongolia`s whenever you walk

and see the distant hills

with houses on their tops.

and banners in every yard.

cherries and peaches on the slopes.

May.

summer begins.

Mongolia es cada vez que caminas

y ver las colinas distantes

con casas en sus cimas.

y banderas en cada patio.

cerezas y melocotones en las laderas.

Mayo.

el verano comienza.

walking across the land

the Japanese girl and her electronic friend

see the hares

or maybe foxes

not hares

scattering from under their feet.

caminando por la tierra

la chica japonesa y su amiga electrónica

ver las liebres

o tal vez zorros

en lugar de liebres

corriendo de debajo de sus pies.

you know, I like

to talk about it.

tu sabes, me gusta

hablar de eso

the matter must have been the robot was lone

but he was not aware of that thing.

and you also was lone.

and then from above

you just brought me some wine.

El problema tenía que ser que el robot estaba solo

Pero él no estaba enterado de eso.

Y tú también estabas solo.

Y luego desde arriba

me acabas de traer un poco de vino

14.

and the Mongols are already sharpening knives

prisoners do not have long to live

y los mongoles ya están afilando cuchillos

los prisioneros no tienen mucho tiempo para vivir

15.

`but

nothing bad happens to us`,

Ryuichi says

`yes, darkness reigns everywhere

due to it every innocent can be puhished unjustly.

everyone can simply disappear

though the war

was over, as-a-matter-of-factly!

`pero

nada malo nos sucede`,

Ryuichi dice

`sí, reina la oscuridad en todas partes

debido a esto, cada inocente puede ser proferido injustamente.

todos pueden simplemente desaparecer

aunque la guerra

había terminado, como una cuestión de hecho!

but I heard radiowaves.

and I called them back in time.

I didn`t want to tell you before the proper time.

soon we`ll meet here

a special Tibetan squad.

its commander informs us he`s glad to be fast

to help

us.

but they need the night

to come

to use their laser

to transform the walls into smoke.

and change night into day.

pero escuché ondas de radio.

y los llamé a tiempo.

No quería decírtelo antes del momento apropiado.

pronto nos encontraremos aquí

un escuadrón tibetano especial.

su comandante nos informa que está contento de ser rápido

ayudar

nos.

pero necesitan tener una noche

para usar su láser

y transformar las paredes en humo.

y cambia la noche en día.

when you wake up.

I`ll be a handsome young

man,

you`ll be adult,

we`ll marry.

I`ll go to work.

on Sundays,

the way it should be,

I`ll sit with my rod on a river bank.

I`ll have a sparkling bucket in my hand.

I`ll always return home

with my catch.

Cuando te despiertas

Seré un joven

apuesto,

Serás adulto,

Nos casaremos.

Iré a trabajar..

Los domingos,

Como debería ser,

Me sentaré con mi caña de pescar en la orilla del río.

Tendré un balde chispeante en mi mano.

Siempre regresaré a casa

Con mi captura de peces.

16.

`and now

if you`re to be bored

we can have a good look at clouds

or just sing aloud something

or simply sit down doing nothing

and expect

when the battle begins

or expect a sign.`

`what sign?`

`y ahora

si estás aburrido

podemos echar un buen vistazo a las nubes

o simplemente cantar en voz alta algo

o simplemente siéntate sin hacer nada

y esperar

cuando comience la batalla

o espera una señal.

`¿Qué señal?`

`a thunderstorm or like.

when you close your eyes

the first rumbles

will make all you like alive

(`may all that you love

meet you after our last mortal kombat`,

whispered to himself the robot)

me,

broken dynasaur,

teddy-bear

and

rice

dog`.

Aug. 16, 2011

(Trans. by Andrew Alexandre Owie)

`una tormenta eléctrica o algo así.

cuando cierras los ojos

los primeros estruendos

darán vida a todo lo que es querido para ti

(`¡Que todos los que amas, te encuentren

después de nuestro último kombate mortal!`,

susurró a sí mismo el robot)

yo,

dinasaur roto,

oso de peluche

y

perro

relleno de arroz`.

16 de agosto de 2011

(Traducido por Andrew Alejandro Owie)

JE T`AIME, MON MINOU, OU UNE COLLECTION DE TANKAS ÉROTIQUES

あなたは叫んだ

私の杖に触れた後

ディープの

沈黙です

ノイズがない

You uttered a shriek

After touching my cane

Deep Silence

No noise

Pronunciaste un grito

Después de tocar mi bastón

El profundo

Silencio Sin ruido

誰があなたの名前をくれたのですか,

島町からの赤ちゃん?

なぜあなたの唇は巧みに

サンゴを撫でる?

至福の天国!

Who gave you your name,

Baby from Shimacho quarter?

Why do your lips so deftly

Stroke the coral?

The seventh heaven of bliss!

¿Quién te dio tu nombre,

Bebé del barrio de Shimacho?

¿Por qué tus labios tan hábilmente

Acarician el coral? ¡

El paraíso de la felicidad!

昨日の正午我々は

至福の杯を

底に排水した

冬の太陽は藤山の上は

とても寂しい

Yesterday at noon

We drained the cup of bliss.

Winter Sun.

It`s so lonesome

Over Fujiyama.

Ayer a mediodía

Bebimos la copa de la bienaventuranza.

Invierno Sol.

Es tan solitario

Sobre Fujiyama.

インとアウト

同じ門を通って

あなたはかなり最近人形を

演奏しました

今あなた別の大人の

ゲームを演奏ます

Ins and outs

Through the same gates.

You`ve played dolls quite recently

Now you play the other

Games with the adult.

Ins y outs

Por las mismas puertas.

Has jugado muñecas muy recientemente.

Ahora juegas los otros juegos

Con los adultos.

あなたはオイルトレーダーを選んだ

私ではない

どれだけの時間?

どこでお金を得ることができますか?

それが問題です

You have preferred me

To an oil trader?

Well, then for how long?

Where to get money?

That`s the problem.

¿Me has preferido

A un comerciante de petróleo?

¿Bueno, por cuánto tiempo?

¿Dónde conseguir dinero?

Ese es el problema.

あなたは笑顔で着物を開いた

あなたの頭を回してください!

なぜ私にこれをするように頼んだのですか?

素晴らしい気持ち

小さなおっぱい

You`ve undone

Your kimono with a smile.

Why have you asked me to turn aside?

Great feelings.

Small boobs.

Has abierto

Su kimono con una sonrisa.

¿Por qué querías que me diera la vuelta?

Grandes sentimientos.

Tetas pequeñas.

誰が致命的な戦争を起こしたのですか?

誰が皇帝の怒りを喚起した?

私は女の子の膝にキスしています。

彼女のシルクスリッパ

露で暗かった。

Who unleashed the fatal war?

Who aroused Emperor`s ire?

I`m kissing the girl`s knees.

Her silk slippers

Have been dark with dew.

¿Quién desencadenó la guerra fatal?

¿Quién despertó la ira del Emperador?

Estoy besando las rodillas de la chica.

Sus zapatillas de seda

Han estado oscuras con el rocío.

ウェットバラ

再咲いた

霧の中で

至福は私の舌の先端に

残っていた

Wet rose

Blossomed again

In fog.

Bliss lingered

On the tip of my tongue.

Rosa húmeda

Volvió a florecer

En la niebla.

La felicidad permaneció más larga

En la punta de la lengua.

(Trans. by Andrew Alexandre Owie/Traducido por Andrew Alejandro Owie)

POETRY UNILLUSTRATED - POESÍA NO ILUSTRADA

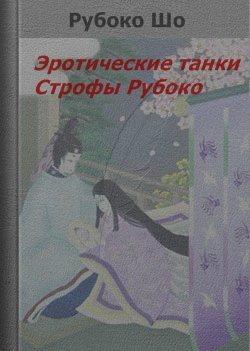

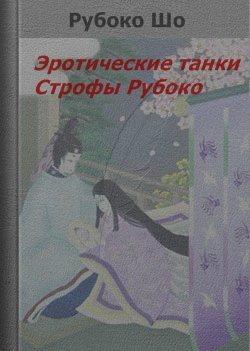

You`ve read the erotic tankas by Ruboku Sho! ¡Ustedes han leído los tankas eróticos por Ruboku Sho!

There remained only 99 tankas of Ruboku Sho (るぼく しょ (路波格 说)). He was a founder of the Japanese erotic poetry. Sólo quedaban 99 tanques de Ruboku Sho. Fue el fundador de la poesía erótica japonesa (るぼく しょでエロティックな短歌).

Kawasaki Inu

As a poet he was occasionally discovered in the Paris bookstalls by a Japanese billionaire Kawasaki Inu (川崎•犬) in the 80s of the 20 c. Como poeta, fue ocasionalmente descubierto en las librerías de París por un billonario japonés Kawasaki Inu en los años 80 del siglo XX.

Kawasaki Inu

In 1985 Mr. Kawasaki died in a brothel in Lisbon in asuspicious contingency. En 1985, el Sr. Kawasaki murió en un burdel de Lisboa en una contingencia sospechosa.

Peter Ingres

The first translations were made by a Canadian philologist Peter Ingres who had got the photo replicas of the manuscripts belonging to the widow Kawasaki Yoko (川崎•洋子).

Kawasaki Yoko

Las primeras traducciones fueron hechas por un filólogo canadiense Peter Ingres que había obtenido réplicas de los manuscritos pertenecientes a la viuda Yoko Kawasaki.

緑の子猫の告白

親愛なる友人!やつかつガール! みんな! あなたが推測しておかなければならないように、るぼく しょ (少)(Ruboku Sho)の短い歌は文学の偽装です。 残念ながら、それは私のものではありません!Mystification は多くの作家によって使用された文学的な装置である。 作家だけでなくスラヴィストでもあったプロスパー・メリメは、西スラヴの歌を書いた。 彼は読者だけでなく多くの傑出した詩人を欺いた。ジェームスマクファーソンは、偽のアイルランドの叙事詩のOssianサイクルを書きました。 Ruboku Shoは同じ行にあります。

Mystification

Green kitty’s confession Confesión del gatito verde

Dear friends! Dudes and dudines! As you must have already guessed, tankas by Ruboku Sho are just a literary mystification. Unfortunately, not mine! Mystification is a literary device which was being used by many writers.

Prosper Mérimée

Prosper Mérimée who was not only writer but also a Slavist wrote The Songs of the Western Slavs. He deceived many outstanding poets, not only readers. James Macpherson wrote the Ossian cycle of the fake Irish epic poems. Ruboku Sho is in the same line.

James Macpherson

¡Queridos amigos! Tíos y tías! Colegas y mujercitas! Como ya has adivinado, tankas por Ruboku Sho son sólo mistificación literaria. Desafortunadamente, no mio! La mistificación es un `dispositivo` literario que fue utilizado por muchos escritores. Prosper Mérimée que no sólo fue escritor sino también eslavista escribió Las canciones de los eslavos occidentales. Engañó a muchos poetas destacados, no sólo a los lectores. James Macpherson escribió el ciclo ossiano de los poemas épicos irlandeses falsos. Ruboku Sho está en la misma línea.

Whom have you called a dog? !¿A quién has llamado un perro?

One day in 1990 Viktor Pelenyagre, a member of the literary group of the `Order of Courtly Mannerists`, a successful author of several lyrics for the then most popular pop songs and an outstanding Russian poet from Moldavia pretended to be an academic translator from the Old Japanese language and offered a quasi-translations made by his friend Oleg Borushko, another member of the `Order of Courtly Mannerists` to one of the Moscow Publishing Houses.

Un vez en 1990, Viktor Pelenyagre, miembro del grupo literario de la Orden de los Manieristas Cortéses, en ese tiempo exitoso autor de varias lyrics para las canciones más populares y un destacado poeta ruso de Moldavia, pretendió ser un traductor académico del Viejo Japonés y ofreció unas cuasi-traducciones hechas por su amigo Oleg Borushko, otro miembro de la Orden de los Manieristas Cortéses, a una de las editoriales de Moscú.

Viktor Pelenyagre

Ruboku Sho is an anagram of Borushko family name. They both wrote quasi-academic comments, preface, tankas. Peter Ingres, the `translator` of tankas was an anagram of the name of Viktor Pelenyagre [pee-lee-nya-gre]. Pelenyagre wrote also many poems for the following books by Ruboku Sho. All those books have been bestsellers in Russia.

Ruboku Sho es un anagrama del apellido de Borushko. Ambos escribieron comentarios cuasiadémicos, prefacio, tankas. Peter Ingres, el "traductor" de tankas era un anagrama del nombre de Viktor Pelenyagre [pee-lee-nya-gre]. Pelenyagre también escribió muchos poemas para los siguientes libros de Ruboku Sho. Todos esos libros han sido best-sellers en Rusia.

Oleg Borushko

Oleg Borushko was one of the Grand Masters of the literary `Order of Courtly Mannerists` of Russia in the 80-90s. Now he lives in London, and is the chairman of the jury of the annual Russian poetry contest `Pushkin in Britain`.

Oleg Borushko fue uno de los Grandes Maestros de la Orden de los Manieristas Cortéses de Rusia en los años 80-90. Ahora vive en Londres y es el presidente del jurado del concurso anual de poesía rusa "Pushkin en Gran Bretaña".

After reading the book`s preface readership was quite sure that it had been a genuine Japanese masterpiece, the more so because the reviewer stated that` in a few lines Ruboku Sho managed to express more shades of meaning than some authors of the thick novels did`. Everybody in Russia, including experts, refused to believe that it was a fake text of an author who never existed in the history of the Japanese literature! Moreover there were issued sequels of the Ruboku Sho. `Abode of one hundred pleasures`. Moscow, Vagrius Publishing House, 2001 and the A Crown for Ruboko and Miscellaneous Works (Poems), 2000, Moscow. Golos Publishing House), etc.

Después de leer los prefacios del libro, los lectores estaban bastante seguros de que había sido una auténtica obra maestra japonesa, más aún porque el crítico afirmó que "en pocas líneas, Ruboku Sho logró expresar más matices de significado que algunos autores de las novelas gruesas `. Todos en Rusia, incluidos los expertos, se negaron a creer que era un texto falso de un autor que nunca existió en la historia de la literatura japonesa. Además, se publicaron secuelas del Ruboku Sho. `Morada de cien placeres`. Moscow, Editorial Vagrius, 2001 y `Una corona para Ruboko y Obras misceláneas (Poemas)`, 2000, Moscú. Golos Editorial), etc.

Ruboku Sho followed the old Russan literary tradition. There were `Japanese` poems written by Konstantin Balmont, Andrei Beliy and Valery Bryusov. An outstanding Russian avant-garde poet Velimir Khlebnikov also composed a cycle of 13 tankas. (Sometimes, it seems Japan in Russia is loved stronger than in Japan itself. It’s a joke, of course, but every single joke contains just a bit of a joke as the Russian are used to jocularly say).

Ruboku Sho siguió la antigua tradición literaria rusa. Había poemas "japoneses" escritos por Konstantin Balmont, Andrei Bely y Valery Bryusov. Un poeta notable de la vanguardia rusa Velimir Khlebnikov también compuso un ciclo de 13 tankas. (A veces, parece que Japón es amado en Rusia más fuerte que en el propio Japón. Es una broma, por supuesto, pero cada broma solo tiene un poco de broma, como jocosamente suelen decir los rusos).

Velemir Khlebnikov

It had been a very successful marketing move, after all. The Publishing Houses made big profit. The authors were not down too. The circulation of the Ruboku Sho`s tankas made up 300 000 copies. Critics attacked the poets after their mystification had been revealed, blamed them for `clumsy` style of their tankas, they attacked them rather seriously in spite of the fact that the poets of the Order of Courtly Mannerists were never serious, but always ironical, humorous and erotic. Ruboku Sho`s tankas have still been very popular with the Russian readers as well as the had been before their unmasking. Now they became a part of the Russian classical literature. Después de todo, fue una movida de marketing muy exitosa. Las casas editoriales obtuvieron grandes ganancias. Los autores tampoco bajaron. La circulación de los tanques de Ruboku Sho compuso 300,000 copias.Los críticos atacaron a los poetas después de revelar su mistificación, los culpó por el estilo "torpe" de sus tankas, los atacaron bastante en serio a pesar de que los poetas de la Orden de los Manieristas Cortéses nunca fueron serios, sino siempre irónicos, humorístico y erótico.Los tankas de Ruboku siguen siendo muy populares entre los lectores rusos, no menos de lo que fueron antes de ser desenmascarados. Ahora se convirtieron en parte de la literatura clásica rusa.

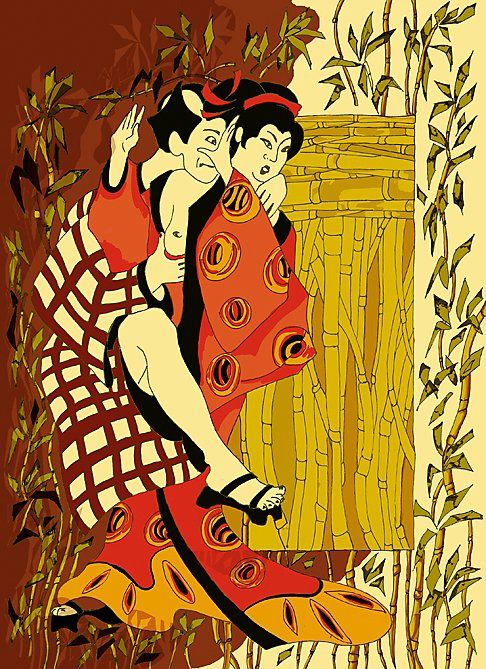

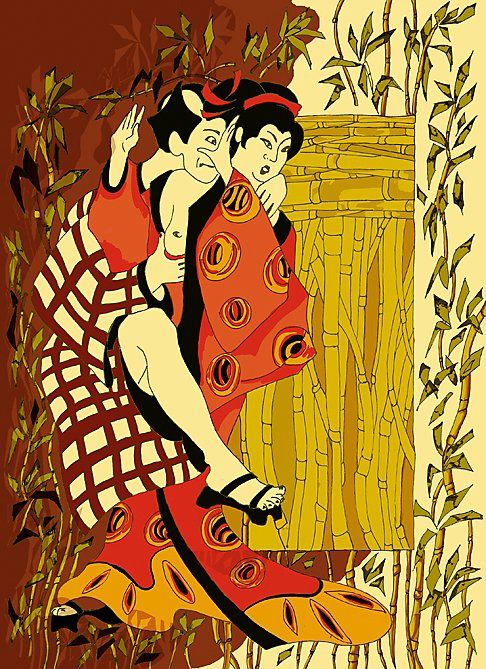

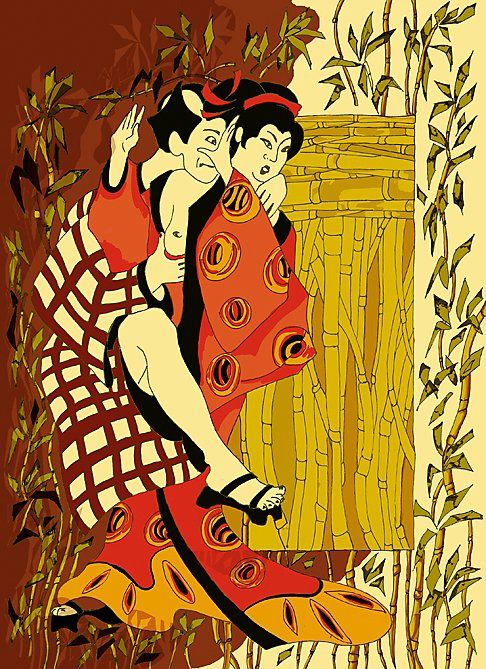

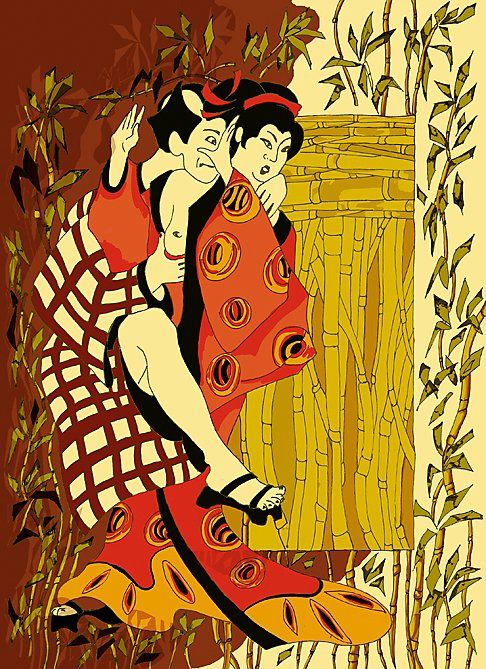

A quasi japanese ukiyo-e by Xenia Tchumakova (an illustration to Ruboku Sho). The picture drawn in the red and yellow palette unusual for the genuine genre of the ukiyo-e pictures. Una ukiyo-e cuasi japonesa por Xenia Chumakova (ilustración à Ruboku Sho). La imagen dibujada en la paleta roja y amarilla inusual para el género genuine de la ukiyo-e.

Japanese translator 緑 の に ゃ ん`s notes : As to me, I had to translate from Russian into Japanese. Not knowing old Japanese I had to use the modern language and its syllabaries, not only hiragana, but also katakana. They were absent in Old Japan, only Chinese characters were used. So the Chinese translations may seem to be closer to the `original`, if not to take into account my usage of the modern grammar. In Old China they also used special language `wenyan`. Besides I transformed the not very Japanese sounding name `Kino Kawabaki` into Inu Kawasaki (lit. Chien Kawasaki), and having probably remembered Serge Gainsbourg (`Je t’aime… moi non plus`, `Qui est in, qui est out `) and A Clockwork Orange (Alex: No time for the old in-n-out, love…), I inserted some English words. Humour! Tee-hee!

Ivan The Terrible: What do you mean, a dog?

緑のにゃんこ(The Green Kitty): Calm down, Ivan Vasiliyevich, I`m just kidding!

Iván el Terrible: ¿Qué quieres decir con un perro?

緑のにゃんこ(El Gatito Verde): Cálmate, Ivan Vasilievich, esto es solo una broma! https://youtu.be/sxqf4uyelUE

Comentarios del traductor japonés 緑のにゃん: En cuanto a mí, tuve que traducir del ruso al japonés. Sin saber japonés antiguo, tuve que usar el lenguaje moderno y sus silabarios, no solo hiragana, sino también katakana. Estaban ausentes en el Japón Antiguo, solo se usaban caracteres chinos. Entonces, las traducciones chinas parecen estar más cerca del 'original', si no para tener en cuenta mi uso de la gramática moderna. En la Antigua China también usaban el lenguaje especial `wenyan`. Además, transformé el nombre no muy japonés `Kino Kawabaki` en Inu Kawasaki (literalmente, Perro Kawasaki) y probablemente recordando a Serge Gainsbourg (` Je t'aime ... moi non plus`, `Qui est in, qui est out`) y Una Naranja Mecánica (Alex: No time for the old in-n-out, love…) inserté algunas palabras en inglés. ¡Humor! ¡Jajaja!

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE Alex: No time for the old in-n-out, love, I've just come to read the meter. https://youtu.be/89GSUhzT3Ow

Tous vedettes! All the celebrities! ¡Todas las celebridades!

Rule, Britannia! ¡Regla, Britannia!

Józef Czelgren. Manual for the Russian Teenagers from the series `Do it yourself!`: `How to get to Japan without a Visa`. Moscow, The Kid-Print Publishing House, 1961

MONGOLIA

By Feodor Swarowski/Por Feodor Swarowski

1.

japanese combat robots

have attacked Beijing.

all the Chinese are dead.

but due to a system failure

they spare no efforts

to ignore a kid.

robots japoneses de combate

han atacado Pekín.

todos los chinos están muertos.

pero debido a una falla del sistema

no escatiman esfuerzos

para ignorar a una niña.

2.

the grass is pushing up asphalt

on deserted Tian`anmen square.

flowers are as far as the eye can see.

electric elephants are roaming about streets.

their riders, the robots,

are all ill.

no more energy.

they need acid to be charged.

no more acid! why?

it has passed

the fifth year

since the start of the genocide.

la hierba está empujando hacia arriba el asfalto

en la plaza desierta de Tian`anmen.

las flores están tan lejos como el ojo puede ver.

elefantes eléctricos están deambulando por las calles.

sus jinetes, los robots,

están todos enfermos.

pas de más energía

necesitan ácido para ser cargado.

¡Pas plus más ácido! ¿Por qué?

ha pasado

el quinto año

desde el comienzo del genocidio.

3.

japanese businessman`s daughter Aiko

lives on the top of a hill

in the ruins of an old house.

outside is a view of the city.

a prison is at the foot of the hill.

she waits for none.

she’s 12, she’s alone every inch.

her only companions are

her torn teddy-bear, dog stuffed with rice.

other plastic fauna without paws and eyes.

food concentrates to expire soon.

there’s only a dozen of boxes

of the spoiled wine.

hija de un empresario japonés Aiko

vive en la cima de una colina

en las ruinas de una casa vieja.

afuera hay una vista de la ciudad.

una prisión está al pie de la colina.

ella no espera a ninguno.

ella tiene 12 años, está sola cada centímetro.

sus únicos compañeros son

su oso de peluche roto, perro relleno de arroz.

otra fauna plástica sin patas y ojos.

los concentrados de alimentos para caducar pronto.

solo hay una docena de cajas

del vino agrio.

4.

in search of a rat for dinner

once she entered the prison`s vault.

darkness and fear!

suddenly she heard someone called

en busca de una rata para la cena

una vez que ella vino debajo los arcos de la prisión.

oscuridad y miedo!

de repente oyó a alguien llamado

`who`s there?`

`girl, girl!

come here, please, try.

I am so alone

I am ill, so on

the demolished cities are still in my eyes`.

`¿quién está allí?`

`niña, niña!

Ven aquí, por favor, inténtalo.

estoy tan solo

Estoy enfermo,

las ciudades demolidas todavía están en mis ojos`.

5.

a boiler in the old house

concealed a replicant.

a robot who`s a human`s replica

was dying of

a heart attack.

una caldera en la casa vieja

ocultó un replicante.

un robot que es una réplica humana

estaba muriendo de

un infarto.

his cardiac muscle made of special fibre

grew weak.

the servoengine gonna stop inside of him.

su músculo cardíaco hecho de fibra especial

se debilitó

la servoingeniería se detendrá dentro de él.

my name is Ryuichi CI 9

I need acid badly

and solar energy.

gimme acid! some acid!

and free me - lemme outside!

mi nombre es Ryuichi CI 9

Realmente necesito ácido

Y energía solar.

¡Dame ácido! ¡Un poco de ácido!

¡Y líbrame, llévame afuera!

6.

Aiko was startled.

that robot

destroyed people.

but he just lay and watched her,

he looked like no enemy, after all.

not like a killer

or like a rogue.

never mind!

thought Aiko.

I am alone, life is mine.

she returned to the cellar

and brought back a glass of wine.

acid in wine helped the robot.

he could stand up,

come out to the streets

and breathe all right.

Aiko se sobresaltó.

ese robot

destruyó la gente.

pero él se quedó allí y la miró.

parecía que no enemigo, después de todo,

no un asesino

o un sinvergüenza.

¡no importa!

pensó Aiko.

Estoy solo, la vida es mía.

ella regresó a la bodega

y trajo una copa de vino.

el ácido en el vino ayudó al robot.

él podría ponerse de pie,

salir a la calle

y respira normalmente

7.

`but to survive all the way

I need to pump

sulfuric and hydrochloric acid in my empty

vessels. badly!

they say, there`s a state of Mongolia in the North

people use there machines and electric light

there might be acid for robots,

confectionery for children and for the adult.`

`do you remember what are sweets, Aiko?`

`no, I don`t remember that staff.`

`pero para recuperar completamente

es necesario bombear ácidos sulfúrico

y clorhídrico a mis vasos. ¡gravemente!

dicen, hay un estado de Mongolia en el norte

la gente usa allí máquinas y luz eléctrica

podría haber ácido para los robots,

dulces para niños y adultos.

`¿Recuerdas qué son los dulces, Aiko? `

`no, no recuerdo esas cosas!

8.

`why to stay all life in the destroyed house?`

decided Aiko.

`time flies.

life promises no changes.

better to dry out several rats,

take wine,

toys

and go

in search of acid and sweets.

may

the robot

atone for his sins

as a fellow traveller of a human being.

if I am tired

then, by the way, he`ll have to carry me!`

'¿por qué quedarse toda la vida en la casa destruida?'

decidió Aiko.

`el tiempo vuela.

la vida no promete cambios.

mejor secar varias ratas,

tomar vino,

juguetes

y ve

en busca de ácido y dulces

deja que el robot

expiar sus pecados

como un compañero de viaje de un ser humano.

si estoy cansado

entonces, por cierto, ¡él tendrá que llevarme!

9.

Aiko thought that `war was fine` as

the whole country was green.

only woods and villages

and cities.

no people – just silence,

water

and torn wires.

only wind,

only

the grass and wind

in the steppe

at nights Ryichi lit the campfires

and said

`while I`m on duty,

you go to bed.`

Aiko pensó que "la guerra estaba bien" como

todo el país era verde.

solo bosques y aldeas

y ciudades

no hay gente, solo silencio,

agua

y cables rotos.

solo viento,

solamente

la hierba y el viento

en la estepa

en las noches, Ryichi encendió las fogatas

y dijo

`mientras estoy de servicio,

te vas a la cama.

10.

they walked ten months to the west,

two months somewhere to the left,

then to the east.

Ryuichi grew faint under a weight.

wine ran out.

he was totally creased.

they lost their way,

Mongolia was faraway.

Aiko got tired

but no longer Ryuichi could carry again

her

in his arms as a babe.

caminaron diez meses hacia el oeste,

dos meses en algún lugar a la izquierda,

luego hacia el este.

Ryuichi se debilitó bajo un peso.

el vino se acabó.

él estaba totalmente exhausto.

perdieron su camino,

Mongolia era lejana.

Aiko se cansó

pero Ryuichi no podía ya llevarlа

su

en sus brazos como un bebé.

11.

once

after waking up in the morning

Aiko

was about

to cry out `Ah!`

wild horsemen noticed them

in the short,

dry grass,

soon caught them up to grasp.

they poped the robot twice

(all went dark before his eyes)

then took them to the city

to lock them behind bars.

una vez que

después de despertarse en la mañana

Aiko casi gritaba ¡Ah!

jinetes salvajes los han notado

pronto en la hierba seca,

y los atrapó para apoderarse.

golpean al robot dos veces

(todo se oscureció ante sus ojos)

luego los llevó a la ciudad

para encerrarlos entre rejas.

12.

this was `Mongolians`

but not Mongolians indeed

no plants

no factories

no acid

no sweets

no power stations

they walked almost bare

every second one professed cannibalism!

esto fue `mongoles`

pero no los mongoles de hecho

sin plantas

sin fábricas

sin ácido

sin dulces

sin estaciones de energía

caminaban casi desnudos

¡cada segundo profesaba canibalismo!

13.

Aiko and Ryuichi

spent ten days, kidnapped,

underground

in expectation of being eaten up.

`Ryuichi, what will be with us? we`re lost!

those people must be wrong Mongols,

not the people we searched for

you know, I`m not afraid,

but I feel emptiness inside

I wish we could fly away

to find out something quite different. ah?

The replicant answered,

`Aiko, there is more to it than meets the eye!

there must have been reason

I fell down

into the vault from above

and had no acid

to later meet you, just fancy!

Aiko y Ryuichi

pasó diez días, secuestrado,

subterráneo

en espera de ser comido.

`Ryuichi, ¿qué pasará con nosotros? estamos perdidos!

esas personas deben no real estar mongoles,

no las personas que buscamos

ya sabes, no tengo miedo,

pero siento vacío dentro

Ojalá pudiéramos irnos volando

para descubrir algo bastante diferente, ah?

El replicante respondió:

`¡Aiko, no es un accidente!

debe haber habido razón

Me caí

en debajo los arcos desde arriba

y no tenía ácido

para luego conocerte, ¡Imagine juste!

true Mongolia must be

placed somewhere else.

Mongolia is the wind and fields

we walked across not once.

and empty houses, you see?

the buildings in bushes

(their floors covered with dust).

and dry flowers, and their seeds!

la verdadera Mongolia debe ser

colocado en otro lugar.

Mongolia es el viento y los campos

donde cruzamos no una vez.

y casas vacías, ¿entiendes?

los edificios en arbustos

(sus pisos cubiertos de polvo).

y flores secas y sus semillas!

Mongolia`s whenever you walk

and see the distant hills

with houses on their tops.

and banners in every yard.

cherries and peaches on the slopes.

May.

summer begins.

Mongolia es cada vez que caminas

y ver las colinas distantes

con casas en sus cimas.

y banderas en cada patio.

cerezas y melocotones en las laderas.

Mayo.

el verano comienza.

walking across the land

the Japanese girl and her electronic friend

see the hares

or maybe foxes

not hares

scattering from under their feet.

caminando por la tierra

la chica japonesa y su amiga electrónica

ver las liebres

o tal vez zorros

en lugar de liebres

corriendo de debajo de sus pies.

you know, I like

to talk about it.

tu sabes, me gusta

hablar de eso

the matter must have been the robot was lone

but he was not aware of that thing.

and you also was lone.

and then from above

you just brought me some wine.

El problema tenía que ser que el robot estaba solo

Pero él no estaba enterado de eso.

Y tú también estabas solo.

Y luego desde arriba

me acabas de traer un poco de vino

14.

and the Mongols are already sharpening knives

prisoners do not have long to live

y los mongoles ya están afilando cuchillos

los prisioneros no tienen mucho tiempo para vivir

15.

`but

nothing bad happens to us`,

Ryuichi says

`yes, darkness reigns everywhere

due to it every innocent can be puhished unjustly.

everyone can simply disappear

though the war

was over, as-a-matter-of-factly!

`pero

nada malo nos sucede`,

Ryuichi dice

`sí, reina la oscuridad en todas partes

debido a esto, cada inocente puede ser proferido injustamente.

todos pueden simplemente desaparecer

aunque la guerra

había terminado, como una cuestión de hecho!

but I heard radiowaves.

and I called them back in time.

I didn`t want to tell you before the proper time.

soon we`ll meet here

a special Tibetan squad.

its commander informs us he`s glad to be fast

to help

us.

but they need the night

to come

to use their laser

to transform the walls into smoke.

and change night into day.

pero escuché ondas de radio.

y los llamé a tiempo.

No quería decírtelo antes del momento apropiado.

pronto nos encontraremos aquí

un escuadrón tibetano especial.

su comandante nos informa que está contento de ser rápido

ayudar

nos.

pero necesitan tener una noche

para usar su láser

y transformar las paredes en humo.

y cambia la noche en día.

when you wake up.

I`ll be a handsome young

man,

you`ll be adult,

we`ll marry.

I`ll go to work.

on Sundays,

the way it should be,

I`ll sit with my rod on a river bank.

I`ll have a sparkling bucket in my hand.

I`ll always return home

with my catch.

Cuando te despiertas

Seré un joven

apuesto,

Serás adulto,

Nos casaremos.

Iré a trabajar..

Los domingos,

Como debería ser,

Me sentaré con mi caña de pescar en la orilla del río.

Tendré un balde chispeante en mi mano.

Siempre regresaré a casa

Con mi captura de peces.

16.

`and now

if you`re to be bored

we can have a good look at clouds

or just sing aloud something

or simply sit down doing nothing

and expect

when the battle begins

or expect a sign.`

`what sign?`

`y ahora

si estás aburrido

podemos echar un buen vistazo a las nubes

o simplemente cantar en voz alta algo

o simplemente siéntate sin hacer nada

y esperar

cuando comience la batalla

o espera una señal.

`¿Qué señal?`

`a thunderstorm or like.

when you close your eyes

the first rumbles

will make all you like alive

(`may all that you love

meet you after our last mortal kombat`,

whispered to himself the robot)

me,

broken dynasaur,

teddy-bear

and

rice

dog`.

Aug. 16, 2011

(Trans. by Andrew Alexandre Owie)

`una tormenta eléctrica o algo así.

cuando cierras los ojos

los primeros estruendos

darán vida a todo lo que es querido para ti

(`¡Que todos los que amas, te encuentren

después de nuestro último kombate mortal!`,

susurró a sí mismo el robot)

yo,

dinasaur roto,

oso de peluche

y

perro

relleno de arroz`.

16 de agosto de 2011

(Traducido por Andrew Alejandro Owie)

JE T`AIME, MON MINOU, OU UNE COLLECTION DE TANKAS ÉROTIQUES

あなたは叫んだ

私の杖に触れた後

ディープの

沈黙です

ノイズがない

You uttered a shriek

After touching my cane

Deep Silence

No noise

Pronunciaste un grito

Después de tocar mi bastón

El profundo

Silencio Sin ruido

誰があなたの名前をくれたのですか,

島町からの赤ちゃん?

なぜあなたの唇は巧みに

サンゴを撫でる?

至福の天国!

Who gave you your name,

Baby from Shimacho quarter?

Why do your lips so deftly

Stroke the coral?

The seventh heaven of bliss!

¿Quién te dio tu nombre,

Bebé del barrio de Shimacho?

¿Por qué tus labios tan hábilmente

Acarician el coral? ¡

El paraíso de la felicidad!

昨日の正午我々は

至福の杯を

底に排水した

冬の太陽は藤山の上は

とても寂しい

Yesterday at noon

We drained the cup of bliss.

Winter Sun.

It`s so lonesome

Over Fujiyama.

Ayer a mediodía

Bebimos la copa de la bienaventuranza.

Invierno Sol.

Es tan solitario

Sobre Fujiyama.

インとアウト

同じ門を通って

あなたはかなり最近人形を

演奏しました

今あなた別の大人の

ゲームを演奏ます

Ins and outs

Through the same gates.

You`ve played dolls quite recently

Now you play the other

Games with the adult.

Ins y outs

Por las mismas puertas.

Has jugado muñecas muy recientemente.

Ahora juegas los otros juegos

Con los adultos.

あなたはオイルトレーダーを選んだ

私ではない

どれだけの時間?

どこでお金を得ることができますか?

それが問題です

You have preferred me

To an oil trader?

Well, then for how long?

Where to get money?

That`s the problem.

¿Me has preferido

A un comerciante de petróleo?

¿Bueno, por cuánto tiempo?

¿Dónde conseguir dinero?

Ese es el problema.

あなたは笑顔で着物を開いた

あなたの頭を回してください!

なぜ私にこれをするように頼んだのですか?

素晴らしい気持ち

小さなおっぱい

You`ve undone

Your kimono with a smile.

Why have you asked me to turn aside?

Great feelings.

Small boobs.

Has abierto

Su kimono con una sonrisa.

¿Por qué querías que me diera la vuelta?

Grandes sentimientos.

Tetas pequeñas.

誰が致命的な戦争を起こしたのですか?

誰が皇帝の怒りを喚起した?

私は女の子の膝にキスしています。

彼女のシルクスリッパ

露で暗かった。

Who unleashed the fatal war?

Who aroused Emperor`s ire?

I`m kissing the girl`s knees.

Her silk slippers

Have been dark with dew.

¿Quién desencadenó la guerra fatal?

¿Quién despertó la ira del Emperador?

Estoy besando las rodillas de la chica.

Sus zapatillas de seda

Han estado oscuras con el rocío.

ウェットバラ

再咲いた

霧の中で

至福は私の舌の先端に

残っていた

Wet rose

Blossomed again

In fog.

Bliss lingered

On the tip of my tongue.

Rosa húmeda

Volvió a florecer

En la niebla.

La felicidad permaneció más larga

En la punta de la lengua.

(Trans. by Andrew Alexandre Owie/Traducido por Andrew Alejandro Owie)

POETRY UNILLUSTRATED - POESÍA NO ILUSTRADA

You`ve read the erotic tankas by Ruboku Sho! ¡Ustedes han leído los tankas eróticos por Ruboku Sho!

There remained only 99 tankas of Ruboku Sho (るぼく しょ (路波格 说)). He was a founder of the Japanese erotic poetry. Sólo quedaban 99 tanques de Ruboku Sho. Fue el fundador de la poesía erótica japonesa (るぼく しょでエロティックな短歌).

Kawasaki Inu

As a poet he was occasionally discovered in the Paris bookstalls by a Japanese billionaire Kawasaki Inu (川崎•犬) in the 80s of the 20 c. Como poeta, fue ocasionalmente descubierto en las librerías de París por un billonario japonés Kawasaki Inu en los años 80 del siglo XX.

Kawasaki Inu

In 1985 Mr. Kawasaki died in a brothel in Lisbon in asuspicious contingency. En 1985, el Sr. Kawasaki murió en un burdel de Lisboa en una contingencia sospechosa.

Peter Ingres

The first translations were made by a Canadian philologist Peter Ingres who had got the photo replicas of the manuscripts belonging to the widow Kawasaki Yoko (川崎•洋子).

Kawasaki Yoko

Las primeras traducciones fueron hechas por un filólogo canadiense Peter Ingres que había obtenido réplicas de los manuscritos pertenecientes a la viuda Yoko Kawasaki.

緑の子猫の告白

親愛なる友人!やつかつガール! みんな! あなたが推測しておかなければならないように、るぼく しょ (少)(Ruboku Sho)の短い歌は文学の偽装です。 残念ながら、それは私のものではありません!Mystification は多くの作家によって使用された文学的な装置である。 作家だけでなくスラヴィストでもあったプロスパー・メリメは、西スラヴの歌を書いた。 彼は読者だけでなく多くの傑出した詩人を欺いた。ジェームスマクファーソンは、偽のアイルランドの叙事詩のOssianサイクルを書きました。 Ruboku Shoは同じ行にあります。

Mystification

Green kitty’s confession Confesión del gatito verde

Dear friends! Dudes and dudines! As you must have already guessed, tankas by Ruboku Sho are just a literary mystification. Unfortunately, not mine! Mystification is a literary device which was being used by many writers.

Prosper Mérimée

Prosper Mérimée who was not only writer but also a Slavist wrote The Songs of the Western Slavs. He deceived many outstanding poets, not only readers. James Macpherson wrote the Ossian cycle of the fake Irish epic poems. Ruboku Sho is in the same line.

James Macpherson

¡Queridos amigos! Tíos y tías! Colegas y mujercitas! Como ya has adivinado, tankas por Ruboku Sho son sólo mistificación literaria. Desafortunadamente, no mio! La mistificación es un `dispositivo` literario que fue utilizado por muchos escritores. Prosper Mérimée que no sólo fue escritor sino también eslavista escribió Las canciones de los eslavos occidentales. Engañó a muchos poetas destacados, no sólo a los lectores. James Macpherson escribió el ciclo ossiano de los poemas épicos irlandeses falsos. Ruboku Sho está en la misma línea.

Whom have you called a dog? !¿A quién has llamado un perro?

One day in 1990 Viktor Pelenyagre, a member of the literary group of the `Order of Courtly Mannerists`, a successful author of several lyrics for the then most popular pop songs and an outstanding Russian poet from Moldavia pretended to be an academic translator from the Old Japanese language and offered a quasi-translations made by his friend Oleg Borushko, another member of the `Order of Courtly Mannerists` to one of the Moscow Publishing Houses.

Un vez en 1990, Viktor Pelenyagre, miembro del grupo literario de la Orden de los Manieristas Cortéses, en ese tiempo exitoso autor de varias lyrics para las canciones más populares y un destacado poeta ruso de Moldavia, pretendió ser un traductor académico del Viejo Japonés y ofreció unas cuasi-traducciones hechas por su amigo Oleg Borushko, otro miembro de la Orden de los Manieristas Cortéses, a una de las editoriales de Moscú.

Viktor Pelenyagre

Ruboku Sho is an anagram of Borushko family name. They both wrote quasi-academic comments, preface, tankas. Peter Ingres, the `translator` of tankas was an anagram of the name of Viktor Pelenyagre [pee-lee-nya-gre]. Pelenyagre wrote also many poems for the following books by Ruboku Sho. All those books have been bestsellers in Russia.

Ruboku Sho es un anagrama del apellido de Borushko. Ambos escribieron comentarios cuasiadémicos, prefacio, tankas. Peter Ingres, el "traductor" de tankas era un anagrama del nombre de Viktor Pelenyagre [pee-lee-nya-gre]. Pelenyagre también escribió muchos poemas para los siguientes libros de Ruboku Sho. Todos esos libros han sido best-sellers en Rusia.

Oleg Borushko

Oleg Borushko was one of the Grand Masters of the literary `Order of Courtly Mannerists` of Russia in the 80-90s. Now he lives in London, and is the chairman of the jury of the annual Russian poetry contest `Pushkin in Britain`.

Oleg Borushko fue uno de los Grandes Maestros de la Orden de los Manieristas Cortéses de Rusia en los años 80-90. Ahora vive en Londres y es el presidente del jurado del concurso anual de poesía rusa "Pushkin en Gran Bretaña".

After reading the book`s preface readership was quite sure that it had been a genuine Japanese masterpiece, the more so because the reviewer stated that` in a few lines Ruboku Sho managed to express more shades of meaning than some authors of the thick novels did`. Everybody in Russia, including experts, refused to believe that it was a fake text of an author who never existed in the history of the Japanese literature! Moreover there were issued sequels of the Ruboku Sho. `Abode of one hundred pleasures`. Moscow, Vagrius Publishing House, 2001 and the A Crown for Ruboko and Miscellaneous Works (Poems), 2000, Moscow. Golos Publishing House), etc.

Después de leer los prefacios del libro, los lectores estaban bastante seguros de que había sido una auténtica obra maestra japonesa, más aún porque el crítico afirmó que "en pocas líneas, Ruboku Sho logró expresar más matices de significado que algunos autores de las novelas gruesas `. Todos en Rusia, incluidos los expertos, se negaron a creer que era un texto falso de un autor que nunca existió en la historia de la literatura japonesa. Además, se publicaron secuelas del Ruboku Sho. `Morada de cien placeres`. Moscow, Editorial Vagrius, 2001 y `Una corona para Ruboko y Obras misceláneas (Poemas)`, 2000, Moscú. Golos Editorial), etc.

Ruboku Sho followed the old Russan literary tradition. There were `Japanese` poems written by Konstantin Balmont, Andrei Beliy and Valery Bryusov. An outstanding Russian avant-garde poet Velimir Khlebnikov also composed a cycle of 13 tankas. (Sometimes, it seems Japan in Russia is loved stronger than in Japan itself. It’s a joke, of course, but every single joke contains just a bit of a joke as the Russian are used to jocularly say).

Ruboku Sho siguió la antigua tradición literaria rusa. Había poemas "japoneses" escritos por Konstantin Balmont, Andrei Bely y Valery Bryusov. Un poeta notable de la vanguardia rusa Velimir Khlebnikov también compuso un ciclo de 13 tankas. (A veces, parece que Japón es amado en Rusia más fuerte que en el propio Japón. Es una broma, por supuesto, pero cada broma solo tiene un poco de broma, como jocosamente suelen decir los rusos).

Velemir Khlebnikov

It had been a very successful marketing move, after all. The Publishing Houses made big profit. The authors were not down too. The circulation of the Ruboku Sho`s tankas made up 300 000 copies. Critics attacked the poets after their mystification had been revealed, blamed them for `clumsy` style of their tankas, they attacked them rather seriously in spite of the fact that the poets of the Order of Courtly Mannerists were never serious, but always ironical, humorous and erotic. Ruboku Sho`s tankas have still been very popular with the Russian readers as well as the had been before their unmasking. Now they became a part of the Russian classical literature. Después de todo, fue una movida de marketing muy exitosa. Las casas editoriales obtuvieron grandes ganancias. Los autores tampoco bajaron. La circulación de los tanques de Ruboku Sho compuso 300,000 copias.Los críticos atacaron a los poetas después de revelar su mistificación, los culpó por el estilo "torpe" de sus tankas, los atacaron bastante en serio a pesar de que los poetas de la Orden de los Manieristas Cortéses nunca fueron serios, sino siempre irónicos, humorístico y erótico.Los tankas de Ruboku siguen siendo muy populares entre los lectores rusos, no menos de lo que fueron antes de ser desenmascarados. Ahora se convirtieron en parte de la literatura clásica rusa.

A quasi japanese ukiyo-e by Xenia Tchumakova (an illustration to Ruboku Sho). The picture drawn in the red and yellow palette unusual for the genuine genre of the ukiyo-e pictures. Una ukiyo-e cuasi japonesa por Xenia Chumakova (ilustración à Ruboku Sho). La imagen dibujada en la paleta roja y amarilla inusual para el género genuine de la ukiyo-e.

Japanese translator 緑 の に ゃ ん`s notes : As to me, I had to translate from Russian into Japanese. Not knowing old Japanese I had to use the modern language and its syllabaries, not only hiragana, but also katakana. They were absent in Old Japan, only Chinese characters were used. So the Chinese translations may seem to be closer to the `original`, if not to take into account my usage of the modern grammar. In Old China they also used special language `wenyan`. Besides I transformed the not very Japanese sounding name `Kino Kawabaki` into Inu Kawasaki (lit. Chien Kawasaki), and having probably remembered Serge Gainsbourg (`Je t’aime… moi non plus`, `Qui est in, qui est out `) and A Clockwork Orange (Alex: No time for the old in-n-out, love…), I inserted some English words. Humour! Tee-hee!

Ivan The Terrible: What do you mean, a dog?

緑のにゃんこ(The Green Kitty): Calm down, Ivan Vasiliyevich, I`m just kidding!

Iván el Terrible: ¿Qué quieres decir con un perro?

緑のにゃんこ(El Gatito Verde): Cálmate, Ivan Vasilievich, esto es solo una broma! https://youtu.be/sxqf4uyelUE

Comentarios del traductor japonés 緑のにゃん: En cuanto a mí, tuve que traducir del ruso al japonés. Sin saber japonés antiguo, tuve que usar el lenguaje moderno y sus silabarios, no solo hiragana, sino también katakana. Estaban ausentes en el Japón Antiguo, solo se usaban caracteres chinos. Entonces, las traducciones chinas parecen estar más cerca del 'original', si no para tener en cuenta mi uso de la gramática moderna. En la Antigua China también usaban el lenguaje especial `wenyan`. Además, transformé el nombre no muy japonés `Kino Kawabaki` en Inu Kawasaki (literalmente, Perro Kawasaki) y probablemente recordando a Serge Gainsbourg (` Je t'aime ... moi non plus`, `Qui est in, qui est out`) y Una Naranja Mecánica (Alex: No time for the old in-n-out, love…) inserté algunas palabras en inglés. ¡Humor! ¡Jajaja!

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE Alex: No time for the old in-n-out, love, I've just come to read the meter. https://youtu.be/89GSUhzT3Ow

Tous vedettes! All the celebrities! ¡Todas las celebridades!

Rule, Britannia! ¡Regla, Britannia!

| Комментировать | « Пред. запись — К дневнику — След. запись » | Страницы: [1] [Новые] |