Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Tim Guan-tin Chien: English Vinglish: People’s journey across the language barrier |

I don’t remember I have ever go to the cinema for a Bollywood movie, but I am glad I enjoyed it very much when I did this for the first time.

The movie remind me of the ESL classes I took. The frustration of not being able to express thoughts in English efficiently echoes the wider range of non-English speaking audiences, evidently by the success of the movie in these traditionally non-Bollywood markets, including Taiwan.

Compare to India, the English-speaking culture is different in Taiwan. English is not the working language of the mess, except for some white-collar works in forgiven companies or tech sectors (e.g., Mozilla in Taiwan). There is indeed a tread (or, “debate”) on wider-adoption of English usage in colleges. And of course, English dominance and culture invasion, and so on and so on.

That said, the English-learning students depicted in the movies are very true. If you only speak English and had (or, having) the experience working with people from other cultures, I wholeheartedly recommend you to see the movie. Pay attention to the thoughts and the minds of these the characters. In retrospect, think about the inherent behavior of these people as they went through their life-long journey of working with you in English.

This is the only reason I wrote this post, in English.

http://blog.timc.idv.tw/posts/english-vinglish-peoples-journey-across-the-language-barrier/

|

|

Gregory Szorc: Python Package Providing Clients for Mozilla Services |

I have a number of Python projects and tools that interact with various Mozilla services. I had authored clients for all these services as standalone Python modules so they could be reused across projects.

I have consolidated all these Python modules into a unified source control repository and have made the project available on PyPI. You can install it by running:

$ pip install mozautomation

Currently included in the Python package are:

- A client for treestatus.mozilla.org

- Module for extracting cookies from Firefox profiles (useful for programmatically getting Bugzilla auth credentials).

- A client for reading and interpretting the JSON dumps of automation jobs

- An interface to a SQLite database to manage associations between Mercurial changesets, bugs, and pushes.

- Rudimentary parsing of commit messages to extract bugs and reviewers.

- A client to obtain information about Firefox releases via the releases API

- A module defining common Firefox source repositories, aliases, logical groups (e.g. twigs and integration trees), and APIs for fetching pushlog data.

- A client for the self serve API

Documentation and testing is currently sparse. Things aren't up to my regular high quality standard. But something is better than nothing.

If you are interested in contributing, drop me a line or send pull requests my way!

http://gregoryszorc.com/blog/2014/01/06/python-package-providing-clients-for-mozilla-services

|

|

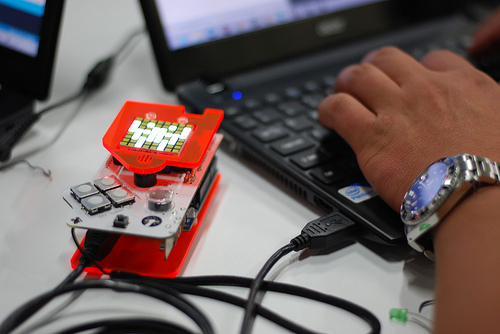

Erik Vold: The FxOS Wrist Watch |

There are many touch screen wrist watches on the market today, and the technology is cheap, I would guess this is because it does not need to be durable, which makes it perfect for the FxOS in my opinion.

The main problem with designing mobile phones first, is that people drop their phones all of the time, so people want to buy the most durable products they can afford, and since Mozilla is not designing hardware we are subjected to being on hardware that may not be designed very well, or that are deisgned to be cheap.

When I recieved my FirefoxOS development phone I was super excited, I instantly swtiched my phone plan off of my iPhone to my FxOS phone. About 5 hours later I dropped the FxOS phone, it broke, it was the first piece of hardware that I had ever broken (it was not the first that I had dropped though). So I had no choice but to go back to my iPhone..

This is a huge problem in my opinion to getting FxOS established in the world as a viable product, we cannot compete with the likes of Google and Apple on the hardware side until FxOS is a popular product, and we can’t make it popular unless it is on some hardware that people want.

So in my opinion releasing/targeting phones first is a bad idea. I feel as though we should be focused on something different and new, like a webby wrist watch.

The FxOS Wrist Watch

A wrist watch does not need to be durable, it is strapped on the wrist, therefore it can be super cheap, which would get FxOS out in the world as quickly as possible.

Furthermore, there needs to be a market of FxOS users before developers and companies are willing to spend time develpoing apps for the product, so again competing in the mobile phone market seems like a bad idea to me (at least to begin with), and if Mozilla tapped in to a new market instead I believe we could push more units of FxOS and attract developers to make things for FxOS.

Lastly, a phone requires many many many features to be useful at all these days, whereas a watch only requires one critical feature, a dope clock. So the requirements to ship a useful product are far smaller, and the team required to make such a product would also be much smaller. One could probably design a cool FxOS watch with the help of one or two other developers and the help of a hardware manufacturer pretty quickly, no need for hundreds of developers and the choas of managing dozens of different default apps.

Anyhow, that was my dream over the holiday break.

http://work.erikvold.com/firefox/2014/01/06/the-fxos-wrist-watch.html

|

|

Karl Dubost: Old browsers, does it matter? |

In computing, we have a tendency to think in terms of very short lifetime. Ed Bott has published an article on zdnet. He is talking about "Old browsers".

The good news for website developers is that modern browsers generally do a good job of rendering standard HTML. For visitors using recent versions of Internet Explorer, Chrome, Firefox, and Safari, most websites will just work.

The emphasis is mine. Indeed that's a good point. The ability of browsers to render old markup (aka old Web sites) with all the quirks is a good thing. A lot of efforts has been put in the recent years on being compatible with what the Web is. HTML5 effort was mainly started with this principle in mind.

The bad news is that not everyone is using a modern browser.

Then the author of the article goes into displaying a graphic about outdated browsers and new browsers. His methodology is explained:

A note about methodology: For Chrome, I considered the most recent version, in this case Chrome 31, plus the one immediately prior, as up to date. I did the same for Firefox, with versions 25 and 26. (I also considered any higher versions from the beta and developer channels as up to date.)

And this is where basically where my personal issue with the article starts. An old browser is an issue if it has security issues aka the user is using something which might create a damage when using it (think data theft, taking over the computer, etc). But for the rest, anyone should be able to use the browser of his/her choice be on an old computer. There are many circumstances where someone will not be able to use the most recent version of a browser. Imagine you get a mobile device which is old enough that it can't be upgraded (browser and OS). Or that using the last version of the browser makes the computer so slow that it becomes a subpar experience. In the last 2 years, browsers vendors have shorten release cycles to every 6 weeks to 9 weeks: Chrome and Firefox. The current computer, I'm using for typing this is 4 years old, 208 weeks. On a 6 weeks schedule, it would mean 35 versions of browsers.

People should not be forced to upgrade their browsers. The modern Web sites should be compatible with browsers which have custom capabilities. A browser like Opera Mini or UCWeb has been specifically designed for environment where the bandwidth or the network is not perfect. It is also very effective for saving money when the price of data is too expensive. The capabilities are not the ones of a recent desktop browsers, but still it's a useful browser. Then there are a full area of browsers which are used for specific needs such as accessibility for example. The author continues with:

All those outdated browsers make web development messy,

What makes the Web development messy is bugs in old browsers, not the version of the browsers. I would even argue that the most recent browsers with their incomplete support of non stabilized technologies—Remember flexbox and CSS gradients—make the Web development messy. This creates plenty of Web compatibility issues. The issue with Web development is that people are tayloring their Web sites to specific browsers and very new technologies which indeed in the end creates plenty of issues for old browsers. The key is to make the Web site robust. Time is the key. The Web site will get wrinkles. It will built history.

Finally in his conclusion, the author mentions

they deliver browser updates, ideally decoupling them completely from operating system releases.

To this, definitely a big yes. That's a big issue. For some mobile devices it's even worse, you have to change device for upgrading the system, which will upgrade the browser. It's quite insane.

So to conclude:

- Old browsers are fine when they don't have security issues

- Web developers should create robust Web sites

Otsukare!

|

|

Luke Wagner: Monkeys |

That’s JaegerMonkey, IonMonkey, and OdinMonkey. I still wish we’d made a shirt for TraceMonkey and Baseline JIT, but then I suppose I’d need more babies.

Credit to John Howard for all three awesome prints:

|

|

Fr'ed'eric Wang: Funding MathML Developments in Gecko and WebKit (part 2) |

As I mentioned three months ago, I wanted to start a crowdfunding campaign so that I can have more time to devote to MathML developments in browsers and (at least for Mozilla) continue to mentor volunteer contributors. Rather than doing several crowdfunding campaigns for small features, I finally decided to do a single crowdfunding campaign with Ulule so that I only have to worry only once about the funding. This also sounded more convenient for me to rely on some French/EU website regarding legal issues, taxes etc. Also, just like Kickstarter it's possible with Ulule to offer some "rewards" to backers according to the level of contributions, so that gives a better way to motivate them.

As everybody following MathML activities noticed, big companies/organizations do not want to significantly invest in funding MathML developments at the moment. So the rationale for a crowdfunding campaign is to rely on the support of the current community and on the help of smaller companies/organizations that have business interest in it. Each one can give a small contribution and these contributions sum up in enough money to fund the project. Of course this model is probably not viable for a long term perspective, but at least this allows to start something instead of complaining without acting ; and to show bigger actors that there is a demand for these developments. As indicated on the Ulule Website, this is a way to start some relationship and to build a community around a common project. My hope is that it could lead to a long term funding of MathML developments and better partnership between the various actors.

Because one of the main demand for MathML (besides accessibility) is in EPUB, I've included in the project goals a collection of documents that demonstrate advanced Web features with native MathML. That way I can offer more concrete rewards to people and federate them around the project. Indeed, many of the work needed to improve the MathML rendering requires some preliminary "code refactoring" which is not really exciting or immediately visible to users...

Hence I launched the crowdfunding campaign the 19th of November and we reached 1/3 of the minimal funding goal in only three days! This was mainly thanks to the support of individuals from the MathML community. In mid december we reached the minimal funding goal after a significant contribution from the KWARC Group (Jacobs University Bremen, Germany) with which I have been in communication since the launch of the campaign. Currently, we are at 125% and this means that, minus the Ulule commision and my social/fiscal obligations, I will be able to work on the project during about 3 months.

I'd like to thank again all the companies, organizations and people who have supported the project so far! The crowdfunding campaign continues until the end of January so I hope more people will get involved. If you want better MathML in Web rendering engines and ebooks then please support this project, even a symbolic contribution. If you want to do a more significant contribution as a company/organization then note that Ulule is only providing a service to organize the crowdfunding campaign but otherwise the funding is legally treated the same as required by my self-employed status; feel free to contact me for any questions on the project or funding and discuss the long term perspective.

Finally, note that I've used my savings and I plan to continue like that until the official project launch in February. Below is a summary of what have been done during the five weeks before the holiday season. This is based on my weekly updates for supporters where you can also find references to the Bugzilla entries. Thanks to the Apple & Mozilla developers who spent time to review my patches!

Collection of documents

The goal is to show how to use existing tools (LaTeXML, itex2MML, tex4ht etc) to build EPUB books for science and education using Web standards. The idea is to cover various domains (maths, physics, chemistry, education, engineering...) as well as Web features. Given that many scientific circles are too much biased by "math on paper / PDF" and closed research practices, it may look innovative to use the Open Web but to be honest the MathML language and its integration with other Web formats is well established for a long time. Hence in theory it should "just work" once you have native MathML support, without any circonvolutions or hacks. Here are a couple of features that are tested in the sample EPUB books that I wrote:

- Rendering of MathML equations (of course!). Since the screen size and resolution vary for e-readers, automatic line breaking / reflowing of the page is "naturally" tested and is an important distinction with respect to paper / PDF documents.

- CSS styling of the page and equations. This includes using (Web) fonts, which are very important for mathematical publishing.

- Using SVG schemas and how they can be mixed with MathML equations.

- Using non-ASCII (Arabic) characters and RTL/LTR rendering of both the text and equations.

- Interactive document using Javascript and

,etc. For those who are curious, I've created some videos for an algebra course and a lab practical. - Using the

element to include short sequences of an experiment in a physics course. - Using the

element to draw graphs of functions or of physical measurements. - Using WebGL to draw interactive 3D schemas. At the moment, I've only adapted a chemistry course and used ChemDoodle to load Crystallographic Information Files (CIF) and provide 3D-representation of crystal structures. But of course, there is not any problem to put MathML equations in WebGL to create other kinds of scientific 3D schemas.

WebKit

I've finished some work started as a MathJax developer, including the maction support requested by the KWARC Group. I then tried to focus on the main goals: rendering of token elements and more specifically operators (spacing and stretching).

- I improved LTR/RTL handling of equations (full RTL support is not implemented yet and not part of the project goal).

- I improved the maction elements and implemented the toggle actiontype.

- I refactored the code of some "mrow-like" elements to make them all behave like an

- I analyzed more carefully the vertical stretching of operators. I see at least two serious bugs to fix: baseline alignment and stretch size. I've uploaded an experimental patch to improve that.

- Preliminary work on the MathML Operator Dictionary. This dictionary contains various properties of operators like spacing and stretchiness and is fundamental for later work on operators.

- I have started to refactor the code for mi, mo and mfenced elements. This is also necessary for many serious bugs like the operator dictionary and the style of mi elements.

- I have written a patch to restore support for foreign objects in annotation-xml elements and to implement the same selection algorithm as Gecko.

Gecko

I've continued to clean up the MathML code and to mentor volunteer contributors. The main goal is the support for the Open Type MATH table, at least for operator stretching.

- Xuan Hu's work on the

- On Linux, I fixed a bug with preferred widths of MathML token elements. Concretely, when equations are used inside table cells or similar containers there is a bug that makes equations overflow the containers. Unfortunately, this bug is still present on Mac and Windows...

- James Kitchener implemented the mathvariant attribute (e.g used by some tools to write symbols like double-struck, fraktur etc). This also fixed remaining issues with preferred widths of MathML token elements. Khaled Hosny started to update his Amiri and XITS fonts to add the glyphs for Arabic mathvariants.

- I finished Quentin Headen's code refactoring of mtable. This allowed to fix some bugs like bad alignment with columnalign. This is also a preparation for future support for rowspacing and columnspacing.

- After the two previous points, it was finally possible to remove the private "_moz-" attributes. These were visible in the DOM or when manipulating MathML via Javascript (e.g. in editors, tree inspector, the html5lib etc)

- Khaled Hosny fixed a regression with script alignments. He started to work on improvements regarding italic correction when positioning scripts. Also, James Kitchener made some progress on script size correction via the Open Type "ssty" feature.

- I've refactored the stretchy operator code and prepared some patches to read the OpenType MATH table. You can try experimental support for new math fonts with e.g. Bill Gianopoulos' builds and the MathML Torture Tests.

Blink/Trident

MathML developments in Chrome or Internet Explorer is not part of the

project goal,

even if obviously MathML improvements to WebKit could

hopefully be imported to Blink in the future. Users keep asking for MathML in IE and I hope that a solution will be found to save MathPlayer's work. In the meantime, I've sent a proposal to Google and Microsoft to implement fallback content (alttext and semantics annotation) so that authors can use it. This is just a couple of CSS rules that could be integrated in the user agent style sheet. Let's see which of the two companies is the most reactive...

|

|

Wil Clouser: Some new Marketplace dashboards |

Cross posting from a mailing list:

I'm pleased to present a couple of dashboards I made over the break for the Marketplace. Behold: 1) How many bugs were closed this week? https://metaplace.paas.allizom.org/bugskiosk/ I actually had the code for that one already laying around, so that was just to see if Andy was taking pull requests on metaplace.2) What waffles are what? https://metaplace.paas.allizom.org/waffles/ A long standing complaint is that it's hard to tell what waffles we have on which site. Not anymore - now you can instantly get two scoops of knowledge as a healthy part of this complete dashboard. (prod's API isn't live so nothing in that column yet) 3) That API seems slow, but maybe it's just me... https://metaplace.paas.allizom.org/apikiosk/ A close runner up in concerns, some of our API speeds have been questionable but it's hard to point to a problem when we're trying to find a graphite graph (behind auth) or it's only happening to you and you can screenshot it but it may just be slow that day or something. Now we have our own personal arewefastyet.com so we can point to real(-time) data on our API speeds (measured from around the world via pingdom). See the other thread on this list ("[RFC] API performance standards") for more thoughts on this Happy 2014!

http://micropipes.com/blog/2014/01/05/some-new-marketplace-dashboards/

|

|

Niko Matsakis: DST, Take 5 |

I believe I have come to the point where I am ready to make a final proposal for DST. Ironically, this proposal is quite similar to where I started, but somewhat more expansive. It seems to be one of those unusual cases where supporting more features actually makes things easier. Thanks to Eridius on IRC for pointing this out to me. I intend for this post to stand alone, so I’m going to start from the beginning in the description.

I am reasonably confident that this DST proposal hangs together because I have taken the time to develop a formal model of Rust and then to extend that model with DST. The model was done in Redex and can be found here. Currently it only includes reduction semantics. I plan a separate blog post describing the model in detail.

Overview

Dynamically sized types

The core idea of this proposal is to introduce two new types [T] and

Trait. [T] represents “some number of instances of T laid out

sequentially in memory”, but the exact number if unknown. Trait

represents “some type T that implements the trait Trait”.

Both of these types share the characteristic that they are

existential variants of existing types. That is, there are

corresponding types which would provide the compiler with full static

information. For example, [T] can be thought of as an instance of

[T, ..n] where the constant n is unknown. We might use the more

traditional – but verbose – notation of exists n. [T, ..n] to

describe the type. Similarly, Trait is an instance of some type T

that implements Trait, and hence could be written exists

T:Trait. T. Note that I do not propose adding existential syntax into

Rust; this is simply a way to explain the idea.

These existential types have an important facet in common: their size

is unknown to the compiler. For example, the compiler cannot compute

the size of an instance of [T] because the length of the array is

unknown. Similarly, the compiler cannot compute the size of an

instance of Trait because it doesn’t know what type that really

is. Hence I refer to these types as dynamically sized – because the

size of their instances is not known at compilation time. More often,

I am sloppy and just call them unsized, because everybody knows that

– to a compiler author, at least – compile time is the only

interesting thing, so if we don’t know the size at compile time, it is

equivalent to not knowing it at all.

Restrictions on dynamically sized types

Because the type (and sometimes alignment) of dynamically sized types

is unknown, the compiler imposes various rules that limit how

instances of such types may be used. In general, the idea is that you

can only manipulate an instance of an unsized type via a pointer. So

for example you can have a local variable of type &[T] (pointer to

array of T) but not [T] (array of T).

Pointers to instances of dynamically sized types are fat pointers –

that means that they are two words in size. The secondary word

describes the “missing” information from the type. So a pointer like

&[T] will consist of two words: the actual pointer to the array, and

the length of the array. Similarly, a pointer like &Trait will

consist of two words: the pointer to the object, and a vtable for Trait.

I’ll cover the full restrictions later, but the most pertinent are:

- Variables and arguments cannot have dynamically sized types.

- Only the last field in a struct may have a dynamically sized type; the other fields must not. Enum arguments must not have dynamically sized types.

unsized keyword

Any type parameter which may be instantiated with an unsized type must

be designed using the unsized keyword. This means that

I originally preferred for all parameters to be unsized by default. However, it seems that the annotation burden here is very high, so for the moment we’ve been rejecting this approach.

The unsized keyword crops up in a few unlikely places. One particular

place that surprised me is in the declaration of traits, where we need

a way to annotate whether the Self type may be unsized. It’s not

entirely clear what this syntax should be. trait Foo,

perhaps? This would rely on Self being a keyword, I suppose. Another

option is trait Foo : unsized, since that is typically where bounds

on Self appear. (TBD)

Bounds in type definitions

Currently we do not permit bounds in type declarations. The reasoning here was basically that, since a type declaration never invokes methods, it doesn’t need bounds, and we could mildly simplify things by leaving them out.

But the DST scheme needs a way to tag type parameters as potentially unsized, which is a kind of bound (in my mind). Moreover, we [also need bounds to handle destructors][drop], so I think this rule against bounds in structs is just not tenable.

Once we permit bounds in structs, we have to decide where to enforce

them. My proposal is that we check bounds on the type of every

expression. Another option is just to check bounds on struct

literals; this would be somewhat more efficient and is theoretically

equivalent, since it ensures that you will not be able to create an

instance of a struct that does not meet the struct’s declared

boundaries. However, it fails to check illegal transmute calls.

Creating an instance of a dynamically sized type

Instances of dynamically sized types are obtained by coercing an existing instance of a statically sized type. In essence, the compiler simply “forgets” a piece of the static information that it used to know (such as the length of the vector); in the process, this static bit of information is converted into a dynamic value and added into the resulting fat pointer.

Intuition

The most obvious cases to be permitted are coercions from built-in

pointer types, such as &[T, ..n] to &[T] or &T to &Trait

(where T:Trait). Less obvious are the rules to support coercions for

smart pointer types, such as Rc<[T, ..n]> being casted to Rc<[T]>.

This is a bit more complex than it appears at first. There are two

kinds of conversions to consider. This is easiest to explain by example.

Let us consider a possible definition for a reference-counting smart

pointer Rc:

struct Rc {

ptr: *RcData,

// In this example, there is no need of more fields, but

// for purposes of illustration we can imagine that there

// are some additional fields here:

dummy: uint

}

struct RcData {

ref_count: uint,

#[max_alignment] // explained later

data: T,

}

From this definition you can see that a reference-counted pointer

consists of a pointer to an RcData struct. The RcData struct

embeds a reference count followed by the data from the pointer itself.

We wish to permit a type like Rc<[T, ..n]> to be cast to a type like

Rc<[T]>. This is shown in the following code snippet.

let rc1: Rc<[T, ..3]> = ...;

let rc2: Rc<[T]> = rc1 as RC<[T]>;

What is interesting here is that the type we are casting to, RC<[T]>,

is not actually a pointer to an unsized type. It is a struct that contains

such a pointer. In other words, we could convert the code fragment above

into something equivalent but somewhat more verbose:

let rc1: Rc<[T, ..3]> = ...;

let rc2: Rc<[T]> = {

let Rc { ptr: ptr1, dummy: dummy1 } = rc1;

let ptr2 = ptr as *RcData<[T]>;

Rc { ptr: ptr2, dummy: dummy }

};

In this example, we have unpacked the pointer (and dummy field) out of

the input rc1 and then cast the pointer itself. This second cast,

from ptr1 to ptr2, is a cast from a thin pointer to a fat pointer.

We then repack the data to create the new pointer. The fields in the

new pointer are the same, but because the ptr field has been

converted from a thin pointer to a fat pointer, the offsets of the

dummy field will be adjusted accordingly.

So basically there are two cases to consider. The first is the literal

conversion from thin pointers to fat pointers. This is relatively

simple and is defined only over the builtin pointer types (currently:

&, *, and ~). The second is the conversion of a struct which

contains thin pointer fields into another instance of that same stuct

type where fields are fat pointers. The next section defines these

rules in more detail.

Conversion rules

Let’s start with the rule for converting thin pointers into fat

pointers. This is based on the relation Fat(T as U) = v. This

relation says that a pointer to T can be converted to a fat pointer

to U by adding the value v. Afterwards, we’ll define the full

rules that define when T as U is permitted.

Conversion from thin to fat pointers

There are three cases to define the Fat() function. The first rule

Fat-Array permits converting a fixed-length array type [T, ..n]

into the type [T] for an of unknown length. The second half of the

fat pointer is just the array length in that case.

Fat-Array:

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Fat([T, ..n] as [T]) = n

The second rule Fat-Object permits a pointer to some type T to be

coerced into an object type for the trait Trait. This rule has three

conditions. The first condition is simply that T must implement

Trait, which is fairly obvious. The second condition is that T

itself must be sized. This is less obvious and perhaps a bit

unfortunate, as it means that even if a type like [int] implements

Trait, we cannot create an object from it. This is for

implementation reasons: the representation of an object is always

(pointer, vtable), no matter the type T that the pointer points

at. If T were dynamically sized, then pointer would have to be a

fat pointer – since we do not known T at compile time, we would

have no way of knowing whether pointer was a thin or fat

pointer. What’s worse, the size of fat pointers would be effectively

unbounded. The final condition in the rule is that the type T has a

suitable alignment; this rule may not be necessary. See Appendix A

for more discussion.

Fat-Object:

T implements Trait

T is sized

T has suitable alignment (see Appendix A)

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Fat(T as Trait) = vtable

The final rule Fat-Struct permits a pointer to a struct type to be

coerced so long as all the fields will still have the same type except

the last one, and the last field will also be a legal coercion. This

rule would therefore permit Fat(RcData<[int, ..3]> as RcData<[int]>)

= 3, for example, but not Fat(RcData.

Fat-Struct:

T_0 ... T_i T_n = field-types(R)

T_0 ... T_i U_n = field-types(R)

Fat(T_n as U_n) = v

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Fat(R as R) = v

Coercion as a whole

Now that we have defined that Fat() function, we can define the full

coercion relation T as U. This relation states that the type T is

coercable to the type U; I’m just focusing on the DST-related

coercions here, though we do in fact do other coercions. The rough

idea is that the compiler allows coercion not only simple pointers but

also structs that include pointers. This is needed to support smart

pointers, as we’ll see.

The first and simplest rule is the identity rule, which states that we

can “convert” a type T into a type T (this is of course just a

memcpy at runtime – note that if T is affine then coercion consumes the

value being converted):

Coerce-Identity:

----------------------------------------------------------------------

T as T

The next rule states that we can convert a thin pointer into a fat pointer

using the Fat() rule that we described above. For now I’ll just give

the rule for unsafe pointers, but analogous rules can be defined for

borrowed pointers and ~ pointers:

Coerce-Pointer:

Fat(T as U) = v

----------------------------------------------------------------------

*T as *U

Finally, the third rule states that we can convert a struct R

into another instance of the same struct R with different type

parameters, so long as all of its fields are pairwise convertible:

Coerce-Struct:

T_0 ... T_n = field-types(R)

U_0 ... U_n = field-types(R)

forall i. T_i as U_i

----------------------------------------------------------------------

R as R

The purpose of this rule is to support smart pointer coercion. Let’s

work out an example to see what I mean. Imagine that I define a smart

pointer type Rc for ref-counted data, building on the RcData type

I introduced earlier:

struct Rc {

data: *RcData

}

Now if I had a ref-counted, fixed-length array of type

Rc<[int, ..3]>, I might want to coerce this into a variable-length

array Rc<[int]>. This is permitted by the Coerce-Struct rule. In

this case, the Rc type is basically a newtyped pointer, so it’s

particularly simple, but we can permit coercions so long as the

individual fields either have the same type or are converted from a

thin pointer into a fat pointer.

These rules as I presented them are strictly concerned with type

checking. The code generation of such casts is fairly

straightforward. The identity relation is a memcpy. The thin-to-fat

pointer conversion consists of copying the thin pointer and adding the

runtime value dictated by the Fat function. The struct conversion is

just a recursive application of these two operations, keeping in mind

that the offset in the destination must be adjusted to account for the

size of the increased size of the fat pointers that are produced.

Working with values of dynamically sized types

Just as with coercions, working with DST values can really be

described in two steps. The first are the builtin operators. These are

only defined over builtin pointer types like &[T]. The second is the

method of converting an instance of a smart pointer type like

RC<[T]> into an instance of a builtin pointer type. We’ll start by

examining the mechanism for converting smart pointers into builtin

pointer types, and then examine the operations themselves.

Side note: custom deref operator

The key ingredients for smart pointer integration is an overloadable

deref operator. I’ll not go into great detail, but the basic idea is

to define various traits that can be implemented by smart pointer

types. The precise details of these types merits a separate post and

is somewhat orthogonal, but let’s just examine the simplest case, the

ImmDeref deref:

trait ImmDeref {

fn deref<'a>(&'a self) -> &'a T;

}

This trait would be implemented by most smart pointer types. The type

parameter T is the type of the smart pointer’s referent. The trait

says that, given a (borrowed) smart pointer instance with lifetime

'a, you can dereference that smart pointer and obtain a borrowed

pointer to the referent with lifetime 'a.

For example, the Rc type defined earlier might implement ImmDeref

as follows:

impl ImmDeref for Rc {

fn deref<'a>(&'a self) -> &'a T {

unsafe {

&(*self.ptr).data

}

}

}

Note: As implied by my wording above, I expect there will be a small number of deref traits, basically to encapsulate different mutability behaviors and other characteristics. I’ll go into this in a separate post.

Indexing into variable length arrays

rustc natively supports indexing into two types: [T] (this is a fat

pointer, where the bounds are known dynamically) and [T, ..n] (a

fixed length array, where the bounds are known statically). In the

first case, the type rules ensure that the [T] value will always be

located as the referent of a fat pointer, and the bounds can be loaded

from the fat pointer and checked dynamically. In the second case, the

bounds are inherent in the type (though they must still be checked,

unless the index is a compile-time constant). In addition, the set of

indexable types can be extended by implementing the Index trait. I

will ignore this for now as it is orthogonal to DST.

To participate in indexing, smart pointer types do not have to do

anything special, they need simply overload deref. For example, given

an expresion r[3] where r has type Rc<[T]>, the compiler will

handle it as follows:

- The type

Rc<[T]>is not indexable, so the compiler will attempt to dereference it as part of the autoderef that is associated with the indexing operator. - Deref succeeds because

Rcimplements theImmDereftrait described above. The type of*ris thus&[T]. - The type

&[T]is not indexable either, but it too can be dereferenced. - We now have an lvalue

**rof type[T]. This type is indexable, so the search completes.

Invoking methods on objects

This works in a similar fashion to indexing. The normal autoderef

process will lead to a type like Rc being converted to

&Trait, and from there method dispatch proceeds as normal.

Drop glue and so on

There are no particular challenges here that I can see. When asked to

drop a value of type [T] or Trait, the information in the fat

pointer should be enough for the compiler to proceed.

By way of example, here is how I imagine Drop would be implemented

for Rc:

impl Drop for Rc {

fn drop<'a>(&'a mut self) {

unsafe {

intrinsics::drop(&mut (*self.ptr).data);

libc::free(self.ptr);

}

}

}

Appendices

A. Alignment for fields of unsized type

There is one interesting subtlety concerning access to fields of type

Trait – in such cases, the alignment of the field’s type is

unknown, which means the compiler cannot statically compute the

field’s offset. There are two options:

- Extract the alignment information from the vtable, which is present, and compute the offset dynamically. More complicated to codegen but retains maximal flexibility.

- Require that the alignment for fields of (potentially) unsized type be

statically specified, or else devise custom alignment rules for such

fields corresponding to the same alignment used by

malloc().

The latter is less flexible in that it implies types with greater

alignment requirements cannot be made into objects, and it also

implies that structs with low-alignment payloads, like RC, may

be bigger than they need to be, strictly speaking.

The other odd thing about solution #2 is that it implies that a generic structure follows separate rules from a specific version of that structure. That is, given declarations like the following:

struct Foo1 { x: T }

struct Foo2 { x: U }

struct Foo3 { x: int }

It is currently true that Foo1, Foo2, and Foo3 are

alike in every particular. But under solution 2 the alignment of

Foo2 may be greater than Foo1 or Foo3 (since the field

x was declared with unsized type U and hence has maximal

alignment).

B. Traits and objects

Currently, we only permit method calls with an object receiver if the method meets two conditions:

- The method does not employ the

Selftype except as the type of the receiver. - The method does not have any type parameters.

The reason for the first restriction is that, in an object, we do not

know what value the type parameter Self is instantiated with, and

therefore we cannot type check such a call. The reason for the second

restriction is that we can only put a single function pointer into the

vtable and, under a monomorphization scheme, we potentially need an

infinite number of such methods in the vtable. (We could lift this

restriction if we supported an “erased” type parameter system, but

that’s orthogonal.)

Under a DST like system, we can easily say that, for any trait Trait

where all methods meet the above restrictions, then the dynamically

sized type Trait implements the trait Trait. This seems rather

logical, since the type Trait represents some unknown type T that

implements Trait. We must however respect the above two

restrictions, since we will still be dispatching calls dynamically.

(It might even be simpler, though less flexible, to just say that we can only create objects for traits that meet the above two restrictions.)

http://smallcultfollowing.com/babysteps/blog/2014/01/05/dst-take-5/

|

|

Jen Fong-Adwent: The Tech Story of Edna |

|

|

Christian Heilmann: Endangered species of the Web: the Link |

Once the Web was a thriving ecosystem of happily evolving, beautiful creatures. Like with any environment, sooner or later man will step in and kill a lot of things – actively or by accident – and diminish the diversity and health of said ecosystem.

In this series we will look at some of the strange animals that make up the Web as we know it, re-introduce them and show how you can do your part to make sure they don’t die out.

We start with the most important part of the Web: the Link.

A Link is what makes the web, well, the web. It is an address where you can access a certain resource. This could be an HTML document (another animal we’ll cover soon), a video, an image, a text file, a server-side script that does things like sending an email – anything really.

In order to make links work two things are needed: a working end point where the Link should point to (URL or URI – for the difference meet a few people who have too much time and not enough social interactions in their lives and discuss) and an interaction that makes a user agent try to fetch the Link. That could be a user typing the URL in an address bar of a browser, a cURL request on a command line or an HTML element pointing to the URL.

Links are kind of magical, insofar that they allow anyone to have a voice and be found. Check Paul Neave’s “Why I create for the web” to read a heartfelt ode to the Link. And it is true; once you managed to publish something at a URL all kind of wonderful things can happen:

- People can go there directly

- Search engines can index it so people can find it searching for similar terms

- Consumers can get the content you published without having to identify themselves and enter their credit card details (like they have to in almost any App Marketplace)

- Consumers can keep the URL for later and share it with others, thus advertising for you without being paid for it

- And much more…

It is the most simple and most effective world-wide, open and free publishing mechanism. That it is why we need to protect them from extinction.

In HTML, the absolutely best animal to use to make it easy for someone to access a URL is an anchor element or A. But of course there are other elements – in essence anything with an href or src attribute is a link out to the Web.

Endangering the interaction part

There are may ways people kill or endanger Links these days. The biggest one is people not using real links and yet expect Web interaction to happen. You can see anchor elements with href attributes of “javascript:void(0)” or “#” and script functionality applied to them (using event handling) to make them load content from the web or point to another resource. Ajax was the big new shiny thing there that made this the practice du jour and so much better than that awful loading of whole documents.

This is not the Web and it will hurt you. In essence these people do something very simple very wrong and then try to cover their tracks by still using anchor elements. Of course you can glue wings on a dog, but you shouldn’t expect it to be able to fly without a lot of assistance afterwards. There is no need for not pointing your anchors to a real, existing URL. If you do that, anything can go wrong and your functionality will still be OK - the person who activated the link will still get to the resource. Of course, that only works if that resource exists where you point to, which does lead to the second problem we have with Links these days.

Cool URLs don’t mutate

The practice of creating script-dependent links has also lead to another mutation of the link which turned out to be a terrible idea: the hashbang URL. This Frankenstein URL used fragment identifiers acting as Web resources, which they are not (try to do a meta refresh to a fragment if you doubt me). Luckily for us, we have the history API in browsers now which means we don’t need to rely on hashbang URLs for single page applications and we can very much redirect real, valid URLs on the server to their intended resource.

The second, big player in the endangerment of the Link is them dying or mutating. One of the traditional ways of dealing with Links to make them happy is to herd them in enclosures like “bookmarks” or “blog posts” or “articles” where you can group them with like-minded Links and even feed them with “tags” and “descriptions”, yummy things Links really love to chew on. Especially the “description” helps a lot – imagine giving a user a hint of what the anchor they click on will take them to. Sounds good, doesn’t it? People would only call those Links they want to play with and not make them run around without really caring for them.

Catch me if you can?

Talking about running around: social media is killing a lot of Links these days using an evil practice called “shortlinking”. Instead of sending the real URL to people to click on or remember we give them a much shorter version, which – though probably easier to remember – is flaky at best.

Every jump from URL to URL until we reach the endpoint we actually wanted to go to is slowing down our web interactions and is a possible point of failure. Try surfing the web on a slow connection that struggles with DNS lookups and you see what I mean.

Instead of herding the real Links and feeding them descriptions and tags we add hashtags to a URL that might or might not redirect to another. Bookmarks, emails and messages do not contain the real endpoint, but one pointing to it, possibly via another one. It is a big game of Chinese Whispers on a DNS lookup and HTTP redirect level.

In essence, there is a lot of hopping around the web happening that doesn’t benefit anyone – neither the end user who clicked on a link nor the maintainer or the resource as their referrers get all messed up. Twitter does not count the full length of the URL any longer but only uses 19 characters for any URL in a tweet (as it uses a t.co redirect under the hood to filter malicious links) thus using URL shorteners in Tweets is a pointless extra.

How can you help to save the Links?

Ensuring the survival of the Link is pretty easy, all you need to do is treat it with respect and make sure it can be found online rather than being disguised behind lots of mock-Links and relying on a special habitat like the flawless execution of scripts.

- If what you put inside a href attribute doesn’t do anything when you copy and paste it into a browser URL field, you’ve killed a Link

- If you post a URL that only redirects to another URL to save some characters, you killed a Link

You can do some very simple steps to ensure the survival of Links though:

- If you read a short article talking about a resource that has a “/via” link, follow all the “via”s and then post the final, real resource in your social media channels (I covered this some time ago in “That /via nonsense (and putting text in images)“)

- Tell everybody about server-side redirects, the history API and that hashbangs will not bring them any joy but are a very short-lived hack

- Do not use social media sharing buttons. Copy and paste the URL instead. A lot of these add yet another shorturl for tracking purposes (btw, you can use the one here, it uses the real URL - damn you almost got to say “isn’t it ironic, that…” and no, it isn’t)

- Read up on what humble elements like A, META and LINK can do

- If you want to interact with scripts and never ever point to a URL, use a BUTTON element – or create the anchor using JavaScript to prevent it from ever showing up when it can’t be used.

Please help us let the Links stay alive and frolic in the wild. It is beautiful sight to behold.

http://christianheilmann.com/2014/01/05/endangered-species-of-the-web-the-link/

|

|

Benjamin Kerensa: Pebble Watchface: MoFox |

If you are as big of an Firefox Fan as I am then surely you want to show off your love for the fox wherever you go and what better way to do that on your wrist? I created a Firefox Watchface called MoFox which you can download right here and start showing off on your Pebble!

If you are as big of an Firefox Fan as I am then surely you want to show off your love for the fox wherever you go and what better way to do that on your wrist? I created a Firefox Watchface called MoFox which you can download right here and start showing off on your Pebble!

This watchface only works on the new Pebble 2.0! I have also published it in the upcoming Pebble Appstore.

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/BenjaminKerensaDotComMozilla/~3/_noZiqozg_4/pebble-watchface-mofox

|

|

Seif Lotfy: Bye Bye Wordpress! Hello Ghost |

Finally managed to move away from Wordpress. One of the reasons I did less blogging is that I felt that Wordpress became more of a CMS and less of a blogging platform.

I stumbled upon ghost which I must say is just awesome... Its done for blogging and blogging only :D

I will be bloging more again now. Recently I have been more active doing upstream openstack development and some sweet Mozilla hacks.

Stay tuned...

|

|

Crystal Beasley: My Nerd Story |

Hi, Paul Graham. My name is Crystal and I’ve been hacking for the past 29 years. I don’t know how you intended your comments but oh lordy, the internet has had a fun time speculating. I’ll leave that commentary to others but I do want to say I’m happy you brought up this debate about gender disparity in tech, as it has sparked some excellent conversation about how we’re going to fix it.

I believe we will fix it in part by having role models. In that spirit, I offer my own nerd story.

I was a poor kid from Arkansas eating government cheese, raised by my grandmother. I didn’t know I was poor. For Christmas 1984, I asked for a computer. Santa brought me a navy and yellow toy computer called a Whiz Kid. I was disappointed. I meant a real computer.

When I was in middle school, I went to a nerd summer camp called “Artificial Intelligence” in 1991 at Harding University. It was my first taste of programming. The language? LISP. Their comp sci department had VAX mainframes to tinker around with Pine email, send the other campers chat messages and use telnet to play text adventure games. My username was Cleopatra on Medievia.

When I was twelve, I saved up $500 and bought an 8088 computer. Remember the 386/486 and the Pentium? This was the one before it. I had enough money to spring for the optional 20MB hard drive, a wise investment. I needed that to save all the images I was about to create with Paint and to play Wolfenstein 3D, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego and QBasic Gorillas. It was on that computer I learned the universal hardware repair rule that you don’t put the case on and screw in all the tiny screws until you’re absolutely sure the new power supply is working.

At fourteen I was programming my TI-85 to graph equations and check my algebra solutions. It’s not clear if it was cheating. I suspect the teachers knew I was going to make the highest grade on the math test regardless.

At seventeen, I had a perfect score, 36, on the science part of the ACT and a 33 in math which qualified me for a generous scholarship. Arkansas doesn’t have an early graduation provision, so I dropped out of high school, took my GED and enrolled in university a whole year early. I majored in computer science. I later added a major in fine art and moved comp sci to be my minor. The natural intersection of design and programming seemed to be web design, which is the field I’m still in.

This career has given me enormous opportunities. I’m typing this from Phnom Penh, Cambodia where I’ve come to volunteer my professional skills to help good causes in developing countries. I travel around the world pushing the web forward as a Product Designer at Mozilla. Before that I was a LOLcat herder for I Can Has Cheezburger. I’ve spoken at conferences in Barcelona, New York and of course, my home in Portland, Oregon. I love the flexibility and creativity of my career, and I’m incredibly fortunate and grateful to live this life.

So what now? If you’re a man, please share this on the social media platform of your choice. Women are half as likely to be retweeted as men. Want to do more? Ask a woman you admire to tell her story. If you’re a woman, write up your nerd origins and share it with the hashtag #mynerdstory. The 13-year-olds of today need role models from every racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. The adult women need role models, like Melinda Byerley who learned HTML and CSS at 42 so she could hack on her startup’s website. We need to hear your story, too.

My Nerd Story is a post from: Crystal Beasley, UX Designer at Mozilla

|

|

Michael Verdi: User Education in everything we do |

Planet Mozilla viewers – you can watch this video on YouTube.

At the Mozilla Summit, Mitchell and Mark talked about education as one of the pillars that underlies our mission. To paraphrase Mark,

“We need to make sure that the whole of the web understands what the web can do for them so they can use it to make their lives better.”

One way we do this is through Webmaker. Right there on webmaker.org it says, we’re dedicated to teaching web literacy. The big Webmaker projects right now (Thimble, X-Ray Goggles, Popcorn) are mainly focused on the “building” literacy. I think the other literacies – exploring and connecting – are also extremely important and possibly relevant to a wider group of people as they include the very basic skills of using a browser (navigation, search, security, privacy, sharing and collaborating).

I also think we have a great opportunity to address exploring and connecting, not only as Webmaker projects, but built right into our products and the experiences that surround them. For example, one of the findings of our North American user type study was that simplified, integrated (in the browser as opposed to the help site), help and support would be a direct thing we could do to help Evergreens and Busy Bees. And, taken together, Evergreens and Busy Bees (plus hybrids that include these types) are our largest group accounting for about 36% of users.

So what would it look like to build user education into everything we do? Well, this new update experience is one example. It might also look like Facebook posts, newsletters, search results, installation dialogs or the product documentation on mozilla.org. This year I’ll begin to work full-time on developing and testing approaches. As a former teacher, the exciting part for me will be what we learn from people. As Mitchell says in the video above,

“Most good teachers will tell you that if you try to teach, you end up learning.”

I couldn’t agree more.

https://blog.mozilla.org/verdi/395/user-education-in-everything-we-do/

|

|

Andrew Truong: Community growth in 2013: we’re ready for 2014 |

Hi all!

Being part of SUMO at Mozilla makes a significant impact! If you have some free time I recommend you to read the latest blog post made by Rosana Ardila:

https://blog.mozilla.org/sumo/2014/01/03/community-growth-in-2013-were-ready-for-2014/

2013 was a great year! It was intense along with the launches of Firefox OS and SUMO providing front end support to the users. Join us to help make 2014 bigger and better!

|

|

Michelle Thorne: Webmaker Community in 2014 |

Here’s a post looking at the principles of the Mozilla Webmaker community and the top-level ways we collectively further these efforts in 2014.

Lots of people are shaping this work, and by next year hopefully many more will have joined in and help Mozilla’s mission spread and scale even more.

Below is a draft of what Chris Lawrence and I nicknamed the “meta-narrative”. It’s an attempt to describe what we’ll be up to in 2014 and why. Thoughts and hacks very welcome!

Our Principles

We believe that empowering human collaboration across open platforms is essential to individual growth and our collective future.

The Webmaker Community team is committed to Mozilla’s mission to build an Internet that is:

- Knowable: it’s transparent–we can see it and understand it

- Interoperable: it presents opportunity to play and innovate

- Ours: it’s open to everyone and we define it

We will be guided by the Connected Learning principles that advocate for learning that is:

- Production centered: it results in deeper learning through making

- Openly networked: it is linked and supported across school, home and community

- Shared purpose: it harnesses the power of the web to foster collaboration around common interests

Weaving together these principles, we aim to:

- Shape environments around creativity, innovation and collaboration

- Build products, programs and practices that help more people learn through making

- Empower communities to participate and iterate on this work

- Teach and learn in ways that are open and give people agency over their own lives

Why Web Literacy

Our experiences, whether digital or analog, are informed by the web. It has become integral to how we see the world and interact with one another. Whether unconsciously or overtly, the web is making us, and we are making it.

Teaching and learning is not immune to this shift; often, people are fearful rather than empowered. How do we improve how people learn with, about and because of the web?

We believe it is essential to become web literate. This means growing our understanding of the:

- culture of the web

- mechanics of the web

- citizenship of the web

Importantly, web literacy is a holistic worldview. It goes beyond simply “learning to code”.

Instead, web literacy acknowledges the blurring between online and offline, and it uses the web to interplay with the world in complex ways.

The Story So far

To address this, we are convening individuals and organizations through networked practice to lead a movement to know more, do more and do better.

In January 2013, we launched our first iteration. The Webmaker Community began testing strategies and programs to catalyze a global web literacy movement with local roots.

We teamed up existing initiatives, like the Hive Learning Network and the Summer Code Party, as well as piloted new offerings, like the Teach the Web MOOC and a map for web literacy.

Now, one year later, these programs continue to spread and scale.

The Webmaker Community

Our community members seek to:

- level up their web literacy

- build and share tools for teaching

- gain peers and networks of practice

- participate in coordinated actions

- identify with a movement that’s globally leveraged and locally contextualized

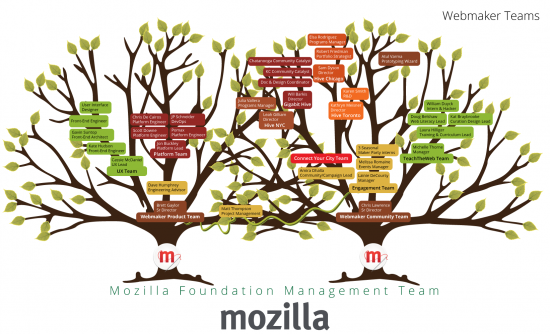

Below is a graph of our “lead users”. These are the types of community members who are most invested in the project. The graph is merely illustrative, not exhaustive. Its purpose is to sample the motivations of our community members and visualize how those compare to one another.

Our Team

In return, we offer our community:

- An open network of networks. Connect to people and organizations seeking to collaborate and innovate.

- Webmaker.org. A holistic and impactful product offering focused on Web Literacy. We will constantly iterate on this offering to surface curricula, tools, badges and user channels that allow our users to become producers of the web. With this product, we will create a differentiated “Web Literacy” space that is parallel to the “learn to code” movement. (webmaker.org)

- Web Literacy. Thought leadership around the skills and competencies of being web literate. (Web Literacy Map)

- Professional development. Improve skills and methods to teach in the open. (Teach the Web)

- Campaigns. Coordinated action that spreads and scales our making-as-learning practices. (Maker Party)

- A contextualized identity. Brands that are globally leveraged and locally adaptable. (Hive Learning Network)

With a more detailed roadmap coming soon.

Here is an overview of the staff supporting and building these offerings:

2014 Events

In 2014, we will facilitate:

- #teachtheweb trainings: January – ongoing, select locations and online

- Hive Summit: February, location tbd

- Webmaker Community Team Work Week: end of the first quarter (tentative), location tbd

- Maker Party: June – September, global

- Mozfest: late October, London

And loads more events in the making.

While this is just a start to our year planning, we really welcome your feedback on the principles and top-level projects. And if you’re interested, do drop a line and get involved!

http://michellethorne.cc/2014/01/webmaker-community-in-2014/

|

|

Mark C^ot'e: BMO in 2013 |

2013 was a pretty big year for BMO! I covered a bit in my last post on BMO, but I want to sum up just some of the things that the team accomplished in 2013 as well as to give you a preview of a few things to come.

We push updates to BMO generally on a weekly basis. The changelog for each push is posted to glob’s blog and linked to from Twitter (@globau) and from BMO’s discussion forum, mozilla.tools.bmo (available via mailing list, Google Group, and USENET).

I’m leaving comments open, but if you have something to discuss, please bring it to mozilla.tools.bmo.

Stats for 2013

BMO Usage:

35 190 new users registered

130 385 new bugs filed

107 884 bugs resolved

BMO Development:

115 code pushes

1 202 new bugs filed

1 062 bugs resolved

Native REST API

2013 saw a big investment in making Bugzilla a platform, not just a tool, for feature and defect tracking (and the other myriad things people use it for!). We completed a native RESTish API to complement the antiquated XMLRPC, JSONRPC, and JSONP interfaces. More importantly, we’ve built out this API to support more and more functionality, such as logging in with tokens, adding and updating flags, and querying the permissions layer.

Something worth taking note of is the bzAPI compatibility layer, which will be deployed in early Q1 of 2014. bzAPI is a nice application which implements a REST interface to Bugzilla through a combination of the legacy APIs, CSV renderings, and screen-scraped HTML. It is, however, essentially a proxy service to Bugzilla, so it has both limited functionality and poorer performance than a native API. With the new bzAPI compatibility layer, site admins will just have to change a URL to take advantage of the faster built-in REST API.

We are also planning to take the best ideas from the old APIs, bzAPI, the newly added functionality, and modern REST interfaces to produce an awesome version 2.0.

Project Kick-off Form

The Project Kick-off Form that was conceived and driven by Michael Coates was launched in January. The BMO team implemented the whole thing in the preceding months and did various improvements over the course of 2013.

The Form is now in the very capable hands of Winnie Aoieong. Winnie did a Project Kick-Off Refresher Brown Bag last month if you want, well, a refresher. We’ll be doing more to support this tool in 2014.

Sandstone Skin

BMO finally got a new default look this year. This was the result of some ideas from the “Bugzilla pretty” contest, the Mozilla Sandstone style guide, and our own research and intuition. BMO is still a far cry from a slick Web 2.x (or are we at 3.0 yet?) site, but it’s a small step towards it.

Oh and we have Gravatar support now!

User Profiles

Want to get some quick stats about a Bugzilla user—how long they’ve been using Bugzilla, the length of their review queue, or the areas in which they’ve been active? Click on a user’s name and select “Profile”, or go directly to your user profile page and enter a name or email into the search field.

File bugs under bugzilla.mozilla.org :: Extensions: UserProfile if there are other stats you think might be useful.

Review Suggestions and Reminders

Code reviews were a big topic at Mozilla in 2013. The BMO team implemented a couple related features:

Reviewer suggestions: When you are flagging a patch for review, you are now presented with a link to a list of one or more suggested reviewers according to the bug’s product and component. This is useful for new contributors who won’t necessarily know who would make a good candidate for review. Given beside the username is the number of reviews in that person’s queue, to encourage spreading reviews out.

Review notifications: As a result of a discussion on code reviews on dev.planning, by default you now get daily emails about your open reviews. You can also subscribe to these notifications for any Bugzilla user, something particularly useful to managers. As a bonus feature, you also get the number of requests assigned to you presented in a small red circle at the top of every Bugzilla page.

System Upgrade

When we upgraded† BMO to Bugzilla 4.2, IT also moved BMO from older hardware in Phoenix to new, faster hardware in SCL3. BMO was then set up anew in Phoenix and is now the failover location in case of an outage in SCL3.

† The BMO team regularly backports particularly useful patches from later upstream Bugzilla versions and trunk, but we fully upgraded to version 4.2 in the spring of 2013.

Other Stuff

We added user and product dashboards, implemented comment tagging, improved bug update times, and added redirects for GitHub pull-request reviews.

And then there were various bits of internal plumbing largely (by design!) invisible to users, such as the great tracking-flags migration; tonnes of little fixes here and there; and of course daily administration.

Plans for 2014

We’re already at work planning and implementing new features to start 2014 off right.

The Bugzilla Change Notification System will be deployed to production. This will allow external applications (and eventually the native UI) to subscribe to one or more bugs via Web Sockets and be notified when they change.

Performance instrumentation will be integrated into BMO (and upstream Bugzilla) to provide profiling data. Bugzilla’s been around for quite some time and, in supporting various complex workflows, its operations in turn can be quite involved. We’ll use data provided by this system to determine where we should focus optimization work.

We added memcached support to Bugzilla in Q4 of 2013; this will be pushed to BMO early in Q1 of 2014. Initially BMO will only use memcached for a few objects, but we’ll be adding more over time.

We’re setting up ElasticSearch clusters to provide a different way to access Bugzilla data, suitable for dashboards and general research.

Code reviews are a continued focus at Mozilla, so we’re implementing a way to get authoritative, comprehensive review data directly from BMO.

Our quarterly goals and other major work items are tracked on the BMO wiki page. You can also check out our road map for some vague ideas of plans into the future; these are ideas based on our current understanding of the Mozillaverse and will almost certainly change to some degree.

|

|

Erik Vold: Jetpack In The Future |

The future for Jetpack is coming, this is what it will look like (as far as I see it).

Native Jetpack

The old days of having to use a command line tool or some add-on builder tool to “build” your jetpacks in to add-ons will be no more, very soon. This is a plan which I have been working on which I call Native Jetpack, you can read far more detailed JEP over here.

Native Jetpack (aka bug 915376), simply put, is a plan to make Jetpacks a native extension type, just like old school extensions, and bootstrap extensions are today. If you were not aware, currently Jetpacks must go through a build process which converts them in to bootstrap extensions, which will no longer be necessary in my Native Jetpack plan. So all that will be required in the future is that the Jetpack be zipped and renamed to use a .xpi file extension (rather than a .zip extension).

The way I came to the conclusion that this was necessary was by dog fooding Jetpacks for many years now, and comparing that experience to my experience making vanilla bootstrap extensions. I realized that I would often change a line or two of code and want to manually test that, which is an easy process with bootstrap extensions and a horrible experience with Jetpacks. With the former I merely had to disable, then enable the extension to see my changes, whereas with the Jetpack extensions I either had to use cfx run which required browser restarts, or I had to use cfx xpi and re-install the extension, which was far less productive than even the cfx run option.

There are other third party options that I have heard of, but they seemed to laborious for even me to bother to figure out, and I feel strongly that the Jetpack project must have a solution for this. There was an existing plan before I joined the team to rewrite the build process in JavaScript (from Python which it is currently written in), and ship this JS implementation with Firefox and have Firefox build the Jetpacks instead of an add-on builder and there was a lot of work done in that direction already, and that is not the same plan as Native Jetpack.

In the Native Jetpack plan the entire build process will be redundant and you therefore will be able to use Jetpacks without any modification.

Please read the JEP if you’d like to know more.

Third Party Modules

Working in parallel to the Native Jetpack project described above is a project to support Node dependencies, this is bug 935109.

In this plan we will drop the old custom made third party dependency support that was developed for Jetpack back in late 2009 early 2010 and just use NPM instead. This makes a lot of sense because almost all of the interesting CommonJS modules exist on NPM at the moment.

Note I did not say we are binding ourseleves to NPM, because we are not, if there is another popular CommonJS package manager then we will utilize that too. The plan is really merely to utilize what is popular.

Rapid Development and Collaboration

Two of the initial goals for the Jetpack project was to make extension development easier and more collabortive. As far as I could tell these were the main reasons why the Add-on Builder was developed. I voiced my concerns about the idea back in January 2010, and in my opinion it failed to achieve it’s mission, and was too expensive, and now it will be shut down.

I do not make decisions on the Jetpack team, I only give my advice like I have since I was a user in 2009 and a ambassador in 2010, and a contributor in 2011 onwards until I was hired to work on the team. So I do not know what the plan is here now, and my ability to predict this stuff is clearly lacking, and there are many options, but this is my hope given the above seems pretty much agreed to at this point.

Once the Native Jetpack plan becomes a reality, there will be no need for special tools to build Jetpacks, one only needs to zip a Jetpack, therefore a large number of options become much easier to implement, and there is very little standing in the way of a lone developer to make their own solutions here, and I hope to see many options bloom and the best ones prosper. However Mozilla should design and implement a solution which is built-in to Firefox in my humble opinion, and my hope is that it looks something like the following.

A dead simple, featureless editor like Scratchpad is available to be used for quickly editing/adding/removing add-on files. That is it. For collboration people will use NPM, Github, Bitbucket, or whatever is popular.

This should be much easier to build, maintain, and pay for than Add-on Builder was I should think (also more useful).

Conclusion

The future is near, and a few team members and I are writing the codes for it now, so please voice your questions and concerns ASAP in the Jetpack mailing list.

http://work.erikvold.com/jetpack/2014/01/03/jetpack-in-the-future.html

|

|

Matej Cepl: Scrapping of the Google Groups |

As a followup to my previous rant on the locked-in nature of the Google Groups, I have created this Python script for scrapping the messages from Google webpages.

Thanks to Sean Hogan for the first inspiration for the script. Any comments would be welcome via email (I am sure you can find my addresses somewhere on the Web) or as a pull requests to my other repo .

http://matej.ceplovi.cz/blog/2014/01/scrapping-of-the-google-groups/

|

|

Sean McArthur: syslogger |

When recently writing an intel-syslog library, I noticed that somehow, npm was lacking a sane syslog library. The popular one, node-syslog, is a giant singleton, meaning it’s impossible to have more than one instance available. That felt wrong. Plus, it’s a native module, and for something so simple, I’d rather not have to compile anything.

That’s where syslogger comes in. It’s pure JavaScript, and has a simple API to allow you to create as many instances as you’d like.

var SysLogger = require('syslogger');

var logger = new SysLogger({

name: 'myApp',

facility: 'user',

address: '127.0.01',

port: 514

});

logger.log(severity, message);

// or

logger.notice(message); //etc

|

|