- Buy 1 lawyer, get 1 free

- Free dental fillings

Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

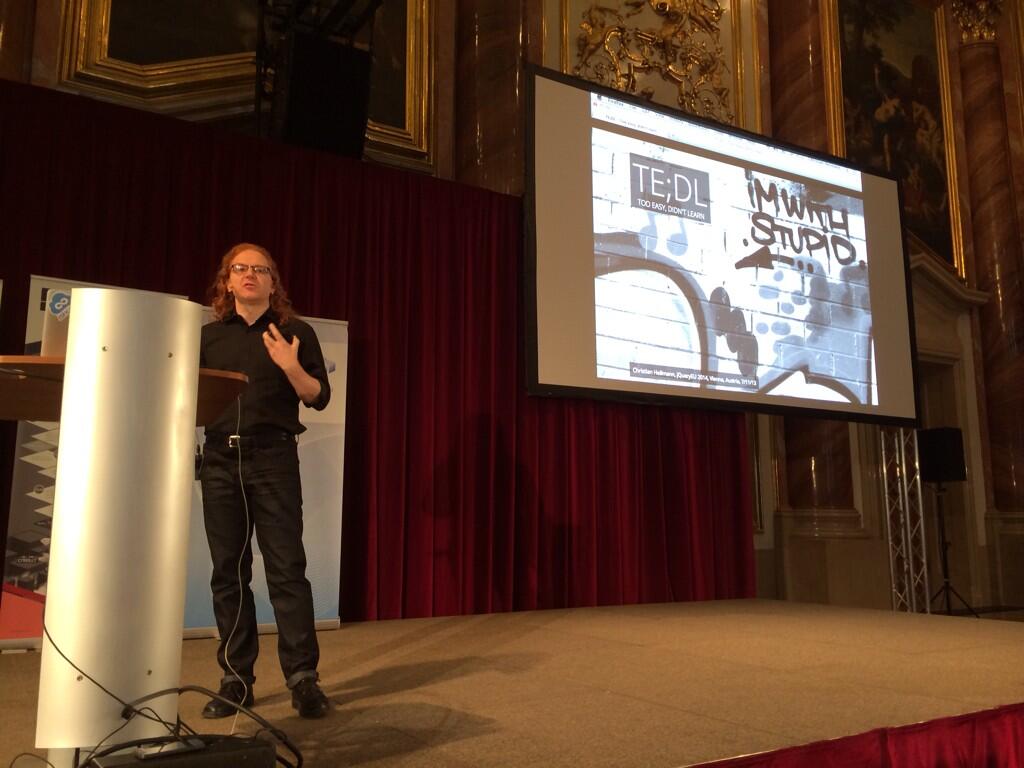

Christian Heilmann: Too easy – didn’t learn – my keynote at jQuery Europe 2014 |

I am right now on the plane back to England after my quick stint at Vienna giving the keynote at jQuery Europe 2014. True to my ongoing task to challenge myself as a speaker (and as announced here before) I made a bit of a bet by giving a talk that is not in itself technical, but analytical of what we do as developers. The talk was filmed and if you can’t wait, I made the slides available and recorded a screencast (with low sound, sorry).

There is also a audio recording on SoundCloud and on archive.org.

Quick keynote recap

In the keynote, I tried to analyse the massive discrepancy between what we as web developers get and how happy we seem to be.

We are an elite group in the job market: we are paid well, our work environment is high-tech and our perks make other people jealous. We even get the proverbial free lunches.

And yet our image is that of unsatisfied, hard to work with people who need to be kept happy and are socially awkward. I was confused that a group with all the necessary creature comforts is not an example of how easy working together could be. Instead, we even seem to need codes of conduct for our events to remind people not to behave badly towards people of the other sex or cultural background. Are we spoiled? Are we just broken? Or is there more?

I’ve found a few reasons why we can come across as unsatisfied and hard to handle and the biggest to me was that whilst we are getting pampered, we lack real recognition for what we do.

When you get a lot, but you yourself feel you are not really doing much, you are stuck between feeling superior to others who struggle with things you consider easy and feeling like a fraud. Instead of trying to communicate out about what we do, how much work it involves and why we do things in a certain way we seem to flee into a world of blaming our tools and trying to impress one another.

Initial Feedback

I am very happy to report that the feedback I got at the event was very good. I had some criticism, which is great as it gives me something to think about. And I had some heartfelt remarks from people who said I’ve opened their eyes a bit as to why they behaved in a certain way and now know how to fix some issues and clashes they had.

Want more?

I don’t want to repeat it all here again – if wanted, I could write a larger article on the subject to be published somewhere with more eyeballs. Simply listen to the recording or wait for the video to be released.

Material

I couldn’t have done this without watching some other talks and reading some other posts, so here are links to the materials used:

- Dan Ariely: what makes us feel good about our work?

- Visa application site for India

- ESTA Visa waiver web site

- Andy Budd: Specialism, Ego and The Dunning-Kruger Effect

- Dunning-Kruger Effect

- Impostor syndrome

- CSS Tricks: A blue box

- Mobile frameworks comparison chart

- Rodney Rehm: thank god we have a specification

Thanks

I want to thank the audience of jQuery Europe for listening and being open to something different. I also want to thank the organisers for taking the chance (and setting the speakers up in the most epic hotel I ever stayed in). I also want to point out that another talk at jQuery Europe 2014 – “A Web Beyond Touch” by Petro Salema was one of the most amazing first stage performances by a speaker I have seen. So keep your eyes open for this video.

http://christianheilmann.com/2014/03/02/too-easy-didnt-learn-my-keynote-at-jquery-europe-2014/

|

|

Andy McKay: Foundations |

As it turns out, software foundations can be pretty useful. There's a tipping point in open source software when all of a sudden money becomes involved and it starts to get serious. Companies are formed, trademarks are violated and all of a sudden, stuff becomes real.

About 10 years ago I was around when Plone went from a small project to a "starting to get serious project". Alexander Limi and Alan Runyan had the foresight right there and then to realise that they needed a foundation, someone to hold the IP and trademarks of Plone. This got it away from being controlled by individuals or companies and instead placed in the community.

The Plone Foundation was formed in 2004 and one of the issues was that a company had been formed, Plone Solutions. in Norway to provide consulting. Having a company with the projects name in the title was a trademark violation. It also leads to confusion within the project and implies a relationship between the company and the project that doesn't exist. The foundation and the company talked and the company amicably changed its name to Jarn instead. Although Jarn is no longer around, Plone is still going strong and so is the Plone Foundation.

As another example, recently the Python Software Foundation had to fight for the Python trademark in Europe when a hosting company tried to trademark Python. The company backed down when the Python community stepped up to help the foundation fight that and proceed with its own trademark.

The Mozilla foundation, not the Mozilla corporation, holds the trademark and intellectual property for Mozilla projects. To commit to a Mozilla project, you have to agree to the committers agreement. Like other foundations it fights against people abusing trademarks. For example, taking Firefox, bundling it up with malware and then distributing it under the Firefox trademark.

In all these cases it's not a company holding trademarks and any intellectual property (depending on the foundation and the software license). Instead a foundation is created by the developers and maintained by the development community. It is the foundations job to act on behalf of the projects software community to maintain and improve it.

And I think Node.js is finding out why it needs one.

Note: I was on the Plone Foundation board, I'm currently the secretary of the Django Software Foundation and I work at Mozilla Corporation (not the Mozilla Foundation)

|

|

Planet Mozilla Interns: Willie Cheong: Mouse / MooseTaste of Good Old Times |

Today I meet Erasmus again after almost 4 long years. Back in Singapore I remember we would hang out with the usuals every other day for lunch/dinner/12am meals. How time has gone by since then. I heard about how everyone was doing well and we had a great time catching up.

Ever since moving to Canada I have often wondered about whether old friends will meet again and despite the years, still have great time hanging out. I occasionally get dreams about meeting my old friends and feeling awkward in the moment because we’ve all changed and been disconnected for so long. The image of these friends frozen in my mind exactly as they were when I last saw them years ago.

Yes, indeed we have changed. The friends we once thought were the best people ever have grown, matured, started new careers, gotten new experiences and built new lives. But friends will always be friends. Meeting with Erasmus today felt good, and sort of heartwarming. It’s like watching Toy Story 3 after many years since Toy Story 2, but way better because this is real life.

http://blog.williecheong.com/mouse-moosetaste-of-good-old-times/

|

|

Priyanka Nag: GNUnify 2014 |

The GNUnify fever gets on all the organizers right from December, but this time, being away from college (because of my job)....I did catch the fever a bit late ;)

Right from 7th of Feb, right from a week before the commencement of the event, I went to college almost every evening; to jump into the excitement of GNUnify preparation. Its very difficult to explain others how we get this passion for the so called EXTRA work after office, but we who live it...just LOVE it!

GNUnify is of-course way more to me than just the Mozilla Dev rooms. This year, the Mozilla Dev rooms were a tough job though...due to the lack of budget.

The last MozCafe meeting that we had before GNUnify was a tricky one. Planning an event like GNUnify with "0" budget is not easy (rather its not possible)....someone we did manage it well with little spending from our own pockets :P

Day one was planned to be a bit different this year. We tried out 'the booth format' (instead of one to one talks, we had project tables (kind of booths) for as many Mozilla projects as we could. There were project experts in each booth) instead of the normal tracks. It wasn't much of a success though. There were several reasons behind the failure of this format on Day one:

- Lack of a proper space- The space provided wasn't exactly a suitable structure for booths.

- Improper crowd management - When in a technical conference, we never like to wait. Initially our booths were sooo much crowded that people had to wait outside the room which eventually ended up in us losing them.

- Improper publicity- Somehow, the entire booth format wasn't well advertised to our audience. The people who visited the Mozilla rooms expected the traditional tracks and were disappointed not to find them.

| |

| A glimpse of the MDN booth on Day I |

Day two went much better. On this day, we had several different tracks like: Webmaker, MDN, Localization, Privacy & Security, Rust, Firefos OS, Reps and FSA. Things went better than expected here. There were sessions like Firefox OS where we had to send some of our audience away due to the lack of sitting space in the Dev rooms.

A few very important learning from GNUnify 2014:

- For any Open Source conference, using Windows OS while making a presentation should be strictly avoided. The Mozillians had to face some criticism as some of our speakers forgot this rule of thumb.

- A little more coordination is required within the team...mainly in situation where we have limited resources and a huge responsibility, everyone needs to understand their role well.

|

|

Soledad Penades: What have I been working on? (2014/02) |

Looking at my todo.txt file, February has pretty much been my speaking-to-everyone month. I spoke to a lot of people from many different teams in Mozilla, and to a lot of people outside of Mozilla for interviews and conferences. Thankfully I also managed to sneak some coding time in it, and even some documenting time!

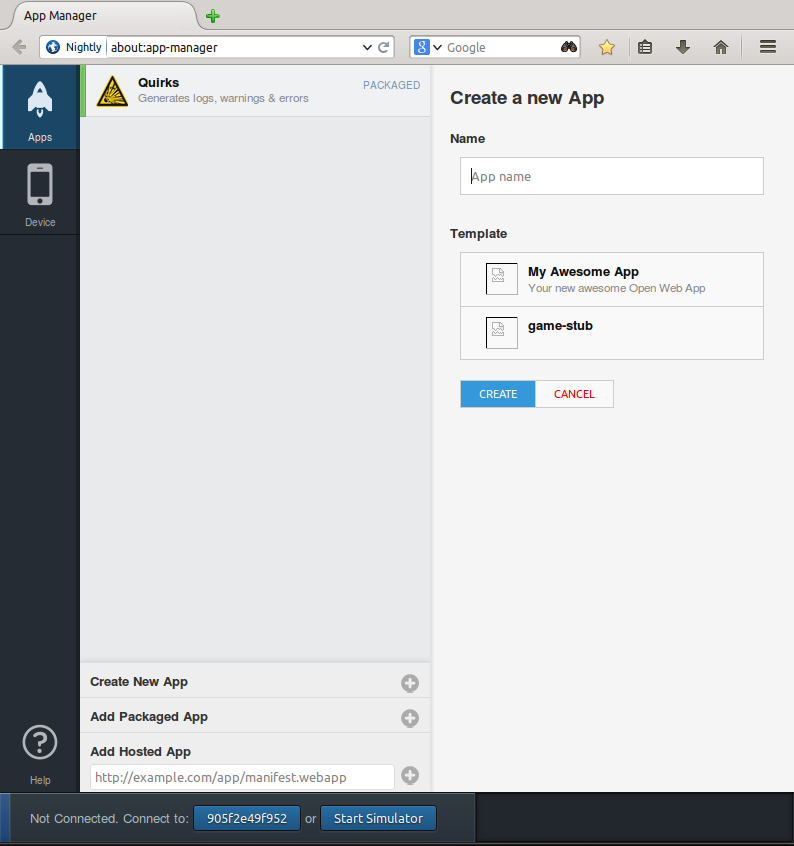

Mozilla-wise: I have mostly been working with DevTools for (I think I can reveal it now) the new “Create new app” feature in App Manager, and the new and improved App Manager itself.

“Create new app” should allow anyone to open the App Manager, choose a template from a list, and get started (you can track it in bug 968808). It’s the evolution of the Mortar project that was started past year, but with a better understanding because we have more experience now (with all the hackdays that happened in 2013 and all the feedback that devrels reported back to us). Here’s an early screenshot:

Also, since us at Apps Engineering do use the App Manager a lot, we also find lots of bugs and things that don’t quite work as we expect them to work, so I had been filing many bugs and giving quite a bit of feedback too.

At some point we realised that we should totally work together instead of “via Bugzilla” only. The people working on the App Manager –Paul Rouget and Jan Keromnes– work in the Paris space, so after a couple of videoconferences we thought it would be most productive if I paid a quick visit to their haunt and we sat for two days discussing everything face to face. And so I did, and that was great!

The fiery stairs at the Mozilla space in Paris

We clarified many aspects that none of us understood too well yet, and I came back to London with a bunch of realisations and ideas to work on. BRAIN. ON. FIRE. Oh, I also came back to find a Tube strike and no buses, and pouring rain, so I had to bike 5 km back to my place and my shoes were wet for two days, but that’s another story.

The next day I had to interview someone for Mozilla, and then I got to be interviewed for Tech Insiders, a website about people working in tech. I’m really proud of the candidate interview as I conducted it in the way I believe in: respectful with the candidate and actually trying to know them and find if they are a good fit: is this a person we would like to work with? how can we help them grow and learn while at Mozilla?

With regards to my interview, I have sort of mixed feelings. I always find it a bit amusing to be interviewed (do people really want to learn about my story?) but then I end up thinking that I forgot to say something important, or that something I said could have been reframed in another way, etc. Anyway, the interview hasn’t been published yet. We’ll see when it’s out.

That same week I made a quick presentation about chat.meatspac.es at the monthly Ladies Who Code meetup, but I already wrote about that.

I kept working on my part of the new features for AppManager –plus filing bugs, pinging people, asking questions–, and two weeks later I flew to Portland because DevTools were having a work week there. It was a long flight with all the connections, but it was well worth it. I learnt a lot about DevTools, put faces to the names I usually see on IRC, I explained the motivations of our team and how we aim to represent and defend the needs and wishes of app developers. Basically: how can we make it easier for people to write apps? We certainly need both libraries and APIs, but also developer tools support, and one of the parts app developers interact a lot with is the App Manager.

So we sat with their UX designer and started iterating and mocking up upcoming features and ideas for the App Manager. Also–I saw the future, and it was really impressive. I can’t wait to see the demoed features land in Firefox. Angelina Fabbro, who was there too, put it like this:

Just finished devtools work week. Wow. The demos. I can't even.

— Angelina Fabbro (@angelinamagnum) February 22, 2014

While at Portland, we also met with people from the Marketplace team –because, you know, Apps, Devtools and Marketplace have to be friends; it doesn’t make sense for them to operate in isolation– and we got some interesting ideas for the future. More to be divulged in later installments of my blog–stay tuned.

I also spoke to the mighty Jordan Santell of Dancer.js fame, because… he actually works in DevTools! We discussed our Web Audio projects, and he demonstrated an early AudioContext inspector panel for DevTools, and if that looks exciting, imagine how the rest of the demos were. We also talked music, jammed with Nick Fitzgerald‘s Maschina and listened to everyone else’s songs–it seemed that suddenly everyone in the room was a musician. So amazing!

Guess who else we met at Portland? Yeah, you guessed it right: the guys from Ember.js, Tom Dale and Yehuda Katz, who came to our office to show how they built their Ember inspector. But it doesn’t stop there. I also stumbled upon Troy Howard –who I’d met at CascadiaJS– on the street, as one does when coming back from a visit to Portland’s legendary food trucks. And we had lunch with Tracy who’s curating this year’s CascadiaJS. I see a theme here…

But there was also time for fun: we visited an amazing place called Ground Kontrol which is full of arcade cabinets and pinballs. Oh, and cheap (by London standards) video game themed cocktails. I had a chance to play Final Fight and TMNT which are some of my favourite arcades ever! Yay!

Pinball!

Cabinets!

And I also gave Angelina the best t-shirt ever, based on the best tweet ever:

.@supersole made me a #webcomponents spec style shirt of a tweet I made to @doge_js ! pic.twitter.com/NcWG90OvbT

— Angelina Fabbro (@angelinamagnum) February 18, 2014

When I made it I thought it was super funny (what with it using the same colour scheme and layout that the W3C spec does!? isn’t it hilarious!?), but I always get insecure before I show things in public. However, judging by the response, I should maybe make more t-shirts! :-)

Before leaving Portland my awesome team mate Edna Piranha and her husband showed me around the city. We had a quick meat up taco lunch with some meatspacers, and then we drove to see nice views. I had to pretend there was a volcano far away but it was hidden by the fog. The trees were really amazing though, same as with the falls, so I can’t complain about what I saw.

One of many beautiful falls

Due to time zones and flight connections I started flying back to London on Saturday and arrived early Monday, so my week so far has been a bit weird, with my body still feeling halfway between PST and GMT times.

Gotta find beauty in the most inane of situations–like waiting for a connection in Houston

We have also been speaking with people from Google so that we all work together on promoting web components. Don’t you think that we only call them when doing WebRTC demos! One of the most recent fruits of these talks is that you can now search for X-Tag based components in the customelements.io registry, thanks to a query string search feature Zeno Rocha implemented. Thus, we no longer have our own X-Tag registry–we are sharing the same registry for all components, be them X-Tag based, Polymer based, or anything-based! Excited is not enough to describe how I feel about this initiative! (Also, did you see this new feature in Firefox?)

I have finally started to document tween.js in my spare moments (which are really few, but bear with me…). You can read the work-in-progress user guide already. There are some missing sections and several TODO items, but it’s getting there. Let me know if you’d like to learn about something in particular!

Oh and you might remember that I promised an article for Mozilla Hacks in my previous installment. Well, I’m not failing you on this; the fact is that it is a bit like the second chapter on a series, and you can’t start a series by publishing the second chapter first (unless you’re George Lucas, and then you start by publishing the fourth episode first).

The first chapter is an article by Angelina, which we raced to finish editing when Angelina’s laptop had only 12% of battery. Ahhh, that sudden rush of adrenaline when the indicator drops down to 1% as you click the Save draft button—will the computer hibernate or will the post be saved before that happens…? But their article can’t be published until Brick 1.0 is released! (it’s currently on a Release Candidate version while some bugs are still ironed out). So you’ll have to wait until mid March, but at least both articles are finished and ready for publishing. Yay! Who knows, I might even start thinking about a ‘third chapter’ in the meantime!

March is looking equally mental in terms of activity, and apparently the conference season opens early for me this year, as I’m going to be on the panel for Web Components at Edge Conf here in London. I’m really humbled and thrilled to have been invited to be there with all these superb co-panelists, so if I turn all red when I’m on stage you now know why.

http://soledadpenades.com/2014/03/01/what-have-i-been-working-on-201402/

|

|

Melissa Romaine: Remix Learning: The Web is the Platform |

Many of you know Mozilla as the makers of the Firefox browser. We’re also breaking into the mobile space with FirefoxOS, and have just announced plans to make a lb15 (USD$25) smartphone. FirefoxOS is a phone operating system, sure, but its bones are web-based. Mozilla is also making educational products and programs like Webmaker, which I’ll share in more detail later.

Remixing is a way to do just that.

When I was teacher drawing up my lesson plans I did exactly this, and I didn’t even know I was remixing. I would take one activity from the curriculum-mandated textbook, find a corresponding YouTube clip, perhaps get the students to apply the idea to their own lives and provide examples, then have a final presentation of sorts – usually outside!

So how can we surface the process so it becomes integral in learning? As educators we often teach skills without being explicit about it. Take writing for example; rarely do we assign worksheets with grammar exercises. Instead, we look for creative, fun ways to introduce, practice, and perfect these skills together as a class. I remember starting or closing class with a little independent writing; it could be diary writing or a reflective entry about something the students experienced that day. Sometimes we wrote plays as a class, bringing in elements of classic stories and adding our own twists. Storyboarding was my favorite activity, where we drew our stories, and then were forced to keep things short and concise when telling it.

The answer to “How can I remix in the classroom?” is “You already do!” But let’s add another element: the web.

Webmaker Tools

Here we have a comic strip created by a student:

Let’s look at the many elements:

- Images

- Colors

- Text

- Speech bubbles

- Placement of the text and speech bubbles

When you click on the remix bottom, you see the code on the left and a preview of your webpage – in this case the comic strip – on the right. By changing the code of certain elements on the left, you change the content of what’s on the right.

First, they’d have to think of the story => exactly the same for any written work. Then they’d have to look for images to fit their story. Students who are good at drawing/graphics could produce their own, upload them, and include them in their comic strip; students who aren’t that good at drawing could look for images that fit their story. We’d be working with their strengths. And then they could fiddle with the background color, the text color, and the placement of the speech bubbles, all of which is customization. Most importantly, they could share their work with their peers, family, and the wider world.

As a teacher or community club member, you can create the template if you’d like: you can choose the images and have learners build the story around them. Or, you could write a vague story and have the student build the story with images. Alternatively, you could have half of the class do one, and the other half do the other. The options are limitless!

We also encourage teachers to remix online, using their own creative lesson plans for content. With our teaching kit template, you can write up your lesson plans and share them with others. Or, you can remix other people’s teaching kits by picking and choosing the bits you want to keep, adding elements from a different resource, and so on. When you create a teaching kit, you can see how other people have remixed it for themselves; you get a visual feedback loop for your own work.

Community

Mozilla promotes this kind of community building all around the world. Make Things Do Stuff is a national network here in the UK, but we have the Hive LearningNetworks that are city-based initiatives, located in Toronto, New York, Chicago, and Pittsburgh. In Japan it’s called Mozilla Factory, and they aren’t focused just on young people. We support many different versions of the approach to promote making.

A Call to Action

http://londonlearnin.blogspot.com/2014/02/remix-learning-web-is-platform.html

|

|

Jen Fong-Adwent: Community and Communication in Virtual Space: The Video |

http://ednapiranha.com/2014/community-and-communication-in-virtual-space/

|

|

Ludovic Hirlimann: Fixing email ... |

A recent twitter thread annoyed me about innovation in email :

E-mail didn’t really evolve since Gmail. Why is it so hard to innovate? http://t.co/Dw3CbqEMqT

— news.yc Popular (@newsycombinator) February 28, 2014

That got me annoyed, because I always here we need to innovate with email and gmail is always taken as a reference in terms of email innovation.

But if you look at it gmail brought the following things to the world :

- unlimited “brokenish imap”

- Dkim/spf to fight spammers

- Good/very good spam filters (using the sender trust level)

- new nice UI to webmail

And that’s it. I’ve been involved with a MUA long enough now that I think email can’t be fixed by ‘just’ UI work or client work. Some things need to happen at the spec level and be implemented on both client and servers.

Unfortunately email has been around for 30ish years now and working for all that time - so fixing and simplifying can’t happen over night.

Let’s make a list of what needs to be fixed client side first :

- The way headers are parsed and handled - way too complicated. Whilst this might have been a necessity 30 years ago I think , that with the email usage we have today it can be simplified. http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5322 Needs to be simplified for headers.

- The way mime is handled - the RFC is 18 years old and needs revisiting, we can probably simplify it too, I don’t believe we need so many ways to send attachments in an email. One should be enough.

- Threading - discard reference-to headers if the subject doesn’t keep any words from the initial subject for instance.

- Make it very easy to unsubscribe from a mailing list.

On the server side there are way more things that need to be fixed

- smtp needs to be replaced with something that would reduce spam and try to keep the identify of the sender (things done today with things like dkim/spf/openpgp).

- mailing list need to be rethought in the way you interact with them - eg digest mode / subscribe / unsubscribe / vacation / cross-posting

- Rich Format email

Of course the last thing to fix is users, why ho why on earth do I get a Microsoft word has an attachment - while I could have directly got the content in the email itself.

|

|

Soledad Penades: Firefox now implementing the latest Custom Element spec |

This week we saw bug 856140 Update document.register to adhere to the latest Custom Element spec fixed. So you can now do things such as declaring and instancing s, which you couldn’t do with the previous implementation, because it would require your custom element’s name to start with an x-, following the old spec. Also, UI libraries such as Brick and other X-Tag based libraries won’t break because the callbacks are never called when web components are enabled. Those are all old bad nightmares from the past!

However the spec isn’t finalised yet–hence you can’t be done implementing something which hasn’t been written yet. And we need people to experiment with web components in Firefox and report bugs if they find them (you can file them under Product = Core, Component = DOM).

If you want to try this out, you can download a Nightly copy and follow the instructions in my Shadow DOM post to enable web components support (it’s disabled by default to prevent “breaking the world”, as Potch would put it).

http://soledadpenades.com/2014/02/28/firefox-now-implementing-the-latest-custom-element-spec/

|

|

Niko Matsakis: Rust RFC: Opt-in builtin traits |

In today’s Rust, there are a number of builtin traits (sometimes

called “kinds”): Send, Freeze, Share, and Pod (in the future,

perhaps Sized). These are expressed as traits, but they are quite

unlike other traits in certain ways. One way is that they do not have

any methods; instead, implementing a trait like Freeze indicates

that the type has certain properties (defined below). The biggest

difference, though, is that these traits are not implemented manually

by users. Instead, the compiler decides automatically whether or not a

type implements them based on the contents of the type.

In this proposal, I argue to change this system and instead have users

manually implement the builtin traits for new types that they define.

Naturally there would be #[deriving] options as well for

convenience. The compiler’s rules (e.g., that a sendable value cannot

reach a non-sendable value) would still be enforced, but at the point

where a builtin trait is explicitly implemented, rather than being

automatically deduced.

There are a couple of reasons to make this change:

- Consistency. All other traits are opt-in, including very common

traits like

EqandClone. It is somewhat surprising that the builtin traits act differently. - API Stability. The builtin traits that are implemented by a type are really part of its public API, but unlike other similar things they are not declared. This means that seemingly innocent changes to the definition of a type can easily break downstream users. For example, imagine a type that changes from POD to non-POD – suddenly, all references to instances of that type go from copies to moves. Similarly, a type that goes from sendable to non-sendable can no longer be used as a message. By opting in to being POD (or sendable, etc), library authors make explicit what properties they expect to maintain, and which they do not.

- Pedagogy. Many users find the distinction between pod types (which copy) and linear types (which move) to be surprising. Making pod-ness opt-in would help to ease this confusion.

- Safety and correctness. In the presence of unsafe code, compiler inference is unsound, and it is unfortunate that users must remember to “opt out” from inapplicable kinds. There are also concerns about future compatibility. Even in safe code, it can also be useful to impose additional usage constriants beyond those strictly required for type soundness.

I will first cover the existing builtin traits and define what they are used for. I will then explain each of the above reasons in more detail. Finally, I’ll give some syntax examples.

The builtin traits

We currently define the following builtin traits:

Send– a type that deeply owns all its contents. (Examples:int,~int, not&int)Freeze– a type which is deeply immutable when accessed via an&Treference. (Examples:int,~int,&int,&mut int, notCellorAtomic)Pod– “plain old data” which can be safely copied via memcpy. (Examples:int,&int, not~intor&mut int)

We are in the process of adding an additional trait:

Share– a type which is threadsafe when accessed via an&Treference. (Examples:int,~int,&int,&mut int,Atomic, notCell)

Proposed syntax

Under this proposal, for a struct or enum to be considered send, freeze, pod, etc, those traits must be explicitly implemented:

struct Foo { ... }

impl Send for Foo { }

impl Freeze for Foo { }

impl Pod for Foo { }

impl Share for Foo { }

For generic types, a conditional impl would be more appropriate:

enum Option { Some(T), None }

impl Send for Option { }

// etc

As usual, deriving forms would be available that would expand into impls like the one shown above.

Whenever a builtin trait is implemented, the compiler will enforce the same requirements it enforces today. Therefore, code like the following would yield an error:

struct Foo<'a> { x: &'a int }

// ERROR: Cannot implement `Send` because the field `x` has type

// `&'a int` which is not sendable.

impl<'a> Send for Foo<'a> { }

These impls would follow the usual coherence requirements. For

example, a struct can only be declared as Share within the crate

where it is defined.

For convenience, I also propose a deriving shorthand

#[deriving(Data)] that would implement a “package” of common traits

for types that contain simple data: Eq, Ord, Clone, Show,

Send, Share, Freeze, and Pod.

Pod and linearity

One of the most important aspects of this proposal is that the Pod

trait would be something that one “opts in” to. This means that

structs and enums would move by default unless their type is

explicitly declared to be Pod. So, for example, the following

code would be in error:

struct Point { x: int, y: int }

...

let p = Point { x: 1, y: 2 };

let q = p; // moves p

print(p.x); // ERROR

To allow that example, one would have to impl Pod for Point:

struct Point { x: int, y: int }

impl Pod for Point { }

...

let p = Point { x: 1, y: 2 };

let q = p; // copies p, because Point is Pod

print(p.x); // OK

Effectively this change introduces a three step ladder for types:

- If you do nothing, your type is linear, meaning that it moves from place to place and can never be copied in any way. (We need a better name for that.)

- If you implement

Clone, your type is cloneable, meaning that it moves from place to place, but it can be explicitly cloned. This is suitable for cases where copying is expensive. - If you implement

Pod, your type is plain old data, meaning that it is just copied by default without the need for an explicit clone. This is suitable for small bits of data like ints or points.

What is nice about this change is that when a type is defined, the user makes an explicit choice between these three options.

Consistency

This change would bring the builtin traits more in line with other

common traits, such as Eq and Clone. On a historical note, this

proposal continues a trend, in that both of those operations used to

be natively implemented by the compiler as well.

API Stability

The set of builtin traits implemented by a type must be considered

part of its public inferface. At present, though, it’s quite invisible

and not under user control. If a type is changed from Pod to

non-pod, or Send to non-send, no error message will result until

client code attempts to use an instance of that type. In general we

have tried to avoid this sort of situation, and instead have each

declaration contain enough information to check it indepenently of its

uses. Issue #12202 describes this same concern, specifically with

respect to stability attributes.

Making opt-in explicit effectively solves this problem. It is clearly

written out which traits a type is expected to fulfill, and if the

type is changed in such a way as to violate one of these traits, an

error will be reported at the impl site (or #[deriving]

declaration).

Pedagogy

When users first start with Rust, ownership and ownership transfer is

one of the first things that they must learn. This is made more

confusing by the fact that types are automatically divided into pod

and non-pod without any sort of declaration. It is not necessarily

obvious why a T and ~T value, which are semantically equivalent,

behave so differently by default. Makes the pod category something you

opt into means that types will all be linear by default, which can

make teaching and leaning easier.

Safety and correctness: unsafe code

For safe code, the compiler’s rules for deciding whether or not a type is sendable (and so forth) are perfectly sound. However, when unsafe code is involved, the compiler may draw the wrong conclusion. For such cases, types must opt out of the builtin traits.

In general, the opt out approach seems to be hard to reason about: many people (including myself) find it easier to think about what properties a type has than what properties it does not have, though clearly the two are logically equivalent in this binary world we programmer’s inhabit.

More concretely, opt out is dangerous because it means that types with

unsafe methods are generally wrong by default. As an example,

consider the definition of the Cell type:

struct Cell {

priv value: T

}

This is a perfectly ordinary struct, and hence the compiler would

conclude that cells are freezable (if T is freezable) and so forth.

However, the methods attached to Cell use unsafe magic to mutate

value, even when the Cell is aliased:

impl Cell {

pub fn set(&self, value: T) {

unsafe {

*cast::transmute_mut(&self.value) = value

}

}

}

To accommodate this, we currently use marker types – special types

known to the compiler which are considered nonpod and so forth. Therefore,

the full definition of Cell is in fact:

pub struct Cell {

priv value: T,

priv marker1: marker::InvariantType,

priv marker2: marker::NoFreeze,

}

Note the two markers. The first, marker1, is a hint to the variance

engine indicating that the type Cell must be invariant with respect

to its type argument. The second, marker2, indicates that Cell is

non-freeze. This then informs the compiler that the referent of a

&Cell can’t be considered immutable. The problem here is that, if

you don’t know to opt-out, you’ll wind up with a type definition that

is unsafe.

This argument is rather weakened by the continued necessity of a

marker::InvariantType marker. This could be read as an argument

towards explicit variance. However, I think that in this particular

case, the better solution is to introduce the Mut type described

in #12577 – the Mut type would give us the invariance.

Using Mut brings us back to a world where any type that uses

Mut to obtain interior mutability is correct by default, at least

with respect to the builtin kinds. Types like Atomic and

Volatile, which guarantee data race freedom, would therefore have

to opt in to the Share kind, and types like Cell would simply

do nothing.

Safety and correctness: future compatibility

Another concern about having the compiler automatically infer membership into builtin bounds is that we may find cause to add new bounds in the future. In that case, existing Rust code which uses unsafe methods might be inferred incorrectly, because it would not know to opt out of those future bounds. Therefore, any future bounds will have to be opt out anyway, so perhaps it is best to be consistent from the start.

Safety and correctness: semantic constraints

Even if type safety is maintained, some types ought not to be copied

for semantic reasons. An example from the compiler is the

Datum type, which is used in code generation to represent

the computed result of an rvalue expression. At present, the type

Rvalue implements a (empty) destructor – the sole purpose of this

destructor is to ensure that datums are not consumed more than once,

because this would likely correspond to a code gen bug, as it would

mean that the result of the expression evaluation is consumed more

than once. Another example might be a newtype’d integer used for

indexing into a thread-local array: such a value ought not to be

sendable. And so forth. Using marker types for these kinds of

situations, or empty destructors, is very awkward. Under this

proposal, users needs merely refrain from implementing the relevant

traits.

The Sized bound

In DST, we plan to add a Sized bound. I do not feel like users

should manually implemented Sized. It seems tedious and rather

ludicrous.

Counterarguments

The downsides of this proposal are:

There is some annotation burden. I had intended to gather statistics to try and measure this but have not had the time.

If a library forgets to implement all the relevant traits for a type, there is little recourse for users of that library beyond pull requests to the original repository. This is already true with traits like

EqandOrd. However, as SiegeLord noted on IRC, that you can often work around the absence ofEqwith a newtype wrapper, but this is not true if a type fails to implementSendorPod. This danger (forgetting to implement traits) is essentially the counterbalance to the “forward compatbility” case made above: where implementing traits by default means types may implement too much, forcing explicit opt in means types may implement too little. One way to mitigate this problem would be to have a lint for when an impl of some kind (etc) would be legal, but isn’t implemented, at least for publicly exported types in library crates.

http://smallcultfollowing.com/babysteps/blog/2014/02/28/rust-rfc-opt-in-builtin-traits/

|

|

Joel Maher: Hi Vaibhav Agrawal, welcome to the Mozilla Community! |

I have had the pleasure to work with Vaibhav for the last 6 weeks as he has joined the Mozilla community as a contributor on the A-Team. As I have watched him grow in his skills and confidence, I thought it would be useful to introduce him and share a bit more about him.

From Vaibhav:

What is your background?

I currently reside in Pilani, a town in Rajasthan, India. The thing that I like the most about where I live is the campus life. I am surrounded by some awesome and brilliant people, and everyday I learn something new and interesting.

I am a third year student pursuing Electronics and Instrumentation at BITS Pilani. I have always loved and been involved in coding and hacking stuff. My favourite subjects so far have been Computer Programming and Data Structures and Algorithms. These courses have made my basics strong and I find the classes very interesting.

I like to code and hack stuff, and I am an open source enthusiast. Also, I enjoy solving algorithmic problems in my free time. I like following new startups and the technology they are working on, running, playing table tennis, and I am a cricket follower.

How did you get involved with Mozilla?

I have been using Mozilla Firefox for many years now. I have recently started contributing to the Mozilla community when a friend of mine encouraged me to do so. I had no idea how the open source community worked and I had the notion that people generally do not have time to answer silly questions and doubts of newcomers. But guess what? I was totally wrong. The contributors in Mozilla are really very helpful and are ready to answer every trivial question that a newbie faces.

Where do you see yourself in 5 years?

I see myself as a software developer solving big problems, building great products and traveling different places!

What advice would you give someone?

Do what you believe in and have the courage to follow your heart and instincts. They somehow know what you truly want to become.

In January :vaibhav1994 popped into IRC and wanted to contribute to a bug that I was a mentor on. This was talos bug 931337, from that first bug Vaibhav has fixed many bugs including work on finalizing our work to support manifests in mochitest. He wrote a great little script to generate patches for bugs 971132 and 970725.

Say hi in IRC and keep an eye out for bugs related to automation where he is uploading patches and fixing many outstanding issues!

http://elvis314.wordpress.com/2014/02/28/hi-vaibhav-agrawal-welcome-to-the-mozilla-community/

|

|

Robert Nyman: Working at Knackeriet – Old Town co-working location |

Let me start by saying that I truly love the Stockholm web scene. So many talented and dedicated people, a bunch of great start-ups and a load of things going on.

When I started Geek Meet in 2006, it was to get the chance for web developers, especially with a front-end focus/interest, to hang out, discuss technology and the web. It’s been a great journey for me, I’ve gotten to know a ton of fantastic people and learn from, and I will continue to arange that for as long as I can.

Nowadays there are lots of great meetups in Stockholm, and I know the people who arrange most of the interesting ones. And there’s no competitive spirit, just a friendly atmosphere where people want to share knowledge, make friends and just have a good time. And I’d like to hope that I was part of setting that bar with Geek Meet, how we should be open, encouraging and sharing.

The next step

In my role working for Mozilla, I’m a remote employee. This means that I work from wherever and whenever I am – as long as I have a laptop and an Internet connection, I can work. This is the life I’ve been leading for the past few years, and most of the time I’ve been working from home – when I haven’t been traveling.

I’ve been contemplating how to get a better day-to-day basis for my work, to meet people, get inspired, bounce ideas. While I do enjoy working from home and am very effective when I do that, the social part definitely shouldn’t be underestimated.

So I’ve been considering options that would make sense, to make my daily live richer and would offer both the social and inspiration parts in one package – basically, an environment that I would thrive in.

Introducing Knackeriet

All this leads to an amazing co-working location in Old Town in Stockholm, Knackeriet. Run by serial web entreprenur Ted Valentin, it is full of very smart, driven and ambitious people, in a very friendly and welcoming setting.

For me it’s very inspiring and motivating to be around great people doing great things!

Ted and I have been talking a bit, and we both want and believe it would be very nice to have lunch presentations and discussions at Knackeriet, hanging out, sharing skills and much more!

Therefore, if you’re in Old Town in Stockholm, I hope you’ll be able to drop by, and we hope we can arrange a number of casual and inspiring meetups here!

|

|

Florian Qu`eze: Google Summer of Code Student who went on to become a Mentor/Org Admin |

Since 2006, I've probably tried every possible role as a Google Summer of Code participant: accepted student, rejected student, submitter of a rejected organization application, mentor of successful students, mentor of a failing student, co-administrator, and now administrator. Here's my story:

- In 2006, I had the pleasure of being selected to participate as a student for the Mozilla organization. The work I did on the Page Info dialog eventually shipped as part of Firefox 3.0.

- In 2007 I applied as a student again, to a different organization, but unfortunately wasn't selected. However, I received an email from someone from the organization who told me the application was good and they would have liked to take me as a student if they had received more slots. He offered to mentor me if I decided to move forward with the project anyway, which I did! I completed the project and in October 2007, Instantbird 0.1 was released. Instantbird is a cross platform, easy to use, instant messaging client based on Mozilla technologies.

- In 2007, I was selected by Mozilla for an internship in the Firefox team, and spent the end of the year in their headquarters in Mountain View, California. I think this was in large part because people were happy about the work I did in 2006 as a Summer of Code student.

- In 2008, 2009 and 2010, I focused on Instantbird, which had a growing community of volunteers improving it every day. I sent Summer of Code organization applications on behalf of the Instantbird community, but they weren't accepted. When I asked for feedback, I was told that we should try to work with Mozilla.

- And this is what we did in 2011! Gerv agreed to let us add Instantbird project ideas to the Mozilla idea list. In 2011 I mentored a student, who completed successfully his work on implementing XMPP in JavaScript for Instantbird. In October I attended the mentor summit in Mountain View.

- In 2012, I mentored another student, who did some excellent work on improving the user experience for new users during the first run of Instantbird.

- In 2013, Gerv, who had been handling Summer of Code for Mozilla since the beginning in 2005, asked me if I would be interested in eventually replacing him as an Administrator. After some discussion, I accepted the offer, and we agreed to have a transition period. In 2013, I was backup administrator. I also mentored for the third year in a row. Unfortunately I had to fail my student. This was frustrating, but also a learning experience.

- In 2014, I submitted the Summer of Code organization application on behalf of Mozilla, it was accepted and we are looking forward to another great summer of code!

- On a more personal note, after being a Mozilla volunteer for years (since 2004), working on the Thunderbird team (from 2011 to 2012), and then on WebRTC apps (since October 2012), I'm starting in March 2014 as a full time engineer in the Firefox team. Which is the team for which I was a Summer of Code student, 8 years ago.

|

|

K Lars Lohn: Redneck Broadband - Disappointing Postscript |

I regret to report that as I leave my friends place in Tennessee, I leave them with very unstable broadband. In my last posting, I reported that we managed to get 28Mps broadband connection the house. That lasted only for a day, and suddenly our source Verizon WiFi hotspot failed to deliver that bandwidth.

I had no idea that cell service was so variable over time. The same equipment that gave us a consistent 4G four bar signal on Monday, now can only get a 3G two bar signal today. In the last forty-eight hours we've been lucky to get an intermittent 200Kbps signal.

[5pm]

We've canvassed the ridge looking for a new location for the WiFi hotspot and finally found a place that consistently delivers a 1Mbps 3G signal. Interestingly, this a place that delivered essentially a zero signal on Monday. The variability of signal strength at a given spot is a serious impediment to success of this project.

Since I leave tomorrow, I'm out of time. There's not much more than I can do on this visit. My hosts are still pleased with the results. The bandwidth is forty-five times faster than the old 28.8Kbps of the old system.

We'll see how this works for the long run. Maybe it will settle into a more consistent pattern. However, I wonder how that will change as Spring comes and the heavily timbered forest of the area leafs out.

I've briefed my hosts on the necessity to monitor the bandwidth and move the hot spot. I had hoped that this would be a set it and forget it installation, but fear this will be a system that will need constant baby sitting.

http://www.twobraids.com/2014/02/redneck-broadband-disappointing.html

|

|

Rick Eyre: Positioning WebVTT In Firefox |

The other day I landed the final patch to get positioning WebVTT in Firefox working. I'd like to share a demo today that I put together to showcase some of the different position settings that Firefox now supports. Note that you'll need to download Firefox Nightly for this to work correctly.

You can checkout the WebVTT file used to make this demo here.

Enjoy!

Thank you to Ali Al Dalla for the video ;-).

The part of the spec that deals with positioning WebVTT cues is called the processing model algorithm and it specifies where to position the cues based on the cue settings that the author has set for each cue and also how to avoid overlap if two or more cues overlap on the video. All this needs to be done manually—positioning boxes absolutely—because the algorithm needs to behave deterministically across browsers.

The algorithm gets the positions for the various cues from the cue settings which are:

- Position—The position from the cue box anchor to where the cue sits on the video.

- Size—The size of the cue in percent of the video.

- Line—The line position on the video; Can be a percent or integer value.

- Align—The text alignment of the cue.

- Vertical—Specifies vertical or horizontal text.

Interestingly enough the hardest part about implementing this part of the standard wasn't the spec itself, but getting the test suite working correctly. The main problem for this is that our test suite isn't hosted in Gecko, but in the vtt.js repo and the algorithm for positioning relies heavily on the positions of computed DOM elements. Since we aren't running the test suite in Gecko we don't have access to a CSS layout engine, which... was a problem.

I tried a lot of different solutions for getting the tests working in vtt.js

and settled on running our test suite with PhantomJS. In the future we'd like to move

it over to using something like Testling so that we can test vtt.js

as a polyfill for older browsers at the same time.

Next up is getting some kind of UI that can control subtitles and the resource selection algorithm.

|

|

Patrick Walton: Revamped Parallel Layout in Servo |

Over the past week I’ve submitted a series of pull requests that significantly revamp the way parallel layout works in Servo. Originally I did this work to improve performance, but it’s also turned out to be necessary to implement more advanced CSS 2.1 features. As it’s a fairly novel algorithm (as far as I’m aware) I’d like to take some time to explain it. I’ll start with where we are in Servo head and explain how it evolved into what’s in my branch. This post assumes a little knowledge about how browser engines work, but little else.

Overview

Servo’s layout operates on a flow tree, which is similar to the render tree in WebKit or Blink and the frame tree in Gecko. We call it a flow tree rather than a render tree because it consists of two separate data types: flows, which are organized in a tree, and boxes, which belong to flows and are organized in a flat list. Roughly speaking, a flow is an object that can be laid out in parallel with other flows, while a box is a box that must be laid out sequentially with other boxes in the same flow. If you’re familiar with WebKit, you can think of a box as a RenderObject, and if you’re familiar with Gecko, you can think of a box as a nsFrame. We want to lay out boxes in parallel as much as possible in Servo, so we group boxes into flows that can be laid out in parallel with one another.

Here’s a simple example. Suppose we have the following document:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this

continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the

proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation,

or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met

on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a

portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave

their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and

proper that we should do this.

This would result in the following flow tree:

Notice that there are three inline boxes under each InlineFlow. We have multiple boxes for each because each contiguous sequence of text in the same style—known as a text run—needs a box. During layout, the structure of the flow tree remains immutable, but the boxes get cut up into separate lines, so there will probably be many more boxes after layout (depending on the width of the window).

One neat thing about this two-level approach is that boxes end up flattened into a flat list instead of a linked data structure, improving cache locality and memory usage and making style recalculation faster because less needs to be allocated. Another benefit (and in fact the original impetus for this data structure) is that the line breaking code need not traverse trees in order to do its work—it only needs to traverse a single array, making the code simpler and improving cache locality.

Now that we know how the flow tree looks, let’s look at how Servo currently performs layout to figure out where boxes should go.

The current algorithm

The current algorithm for parallel layout in Servo (i.e. what’s in the master branch before my changes) consists of three separate passes over the flow tree.

Intrinsic width calculation or

bubble_widths(bottom-up). This computes the minimum width and preferred width for each flow. There are no sequential hazards here and this can always be computed in parallel. Note that this is information is not always needed during layout, and eventually we will probably want to implement optimizations to avoid computation of this information for subtrees in which it is not needed.Actual width calculation or

assign_widths(top-down). This computes the width of each flow, along with horizontal margins and padding values.Height calculation or

assign_heights(bottom-up). This computes the height of each flow. Along the way, line breaking is performed, and floats are laid out. We also compute vertical margins and padding, including margin collapse.

Within each flow, boxes are laid out sequentially—this is necessary because, in normal text, where to place the next line break depends on the lines before it. (However, we may be able to lay boxes out in parallel for white-space: nowrap or white-space: pre.)

For simple documents that consist of blocks and inline flows, Servo achieves excellent parallel wins, in line with Leo Meyerovich’s “Fast and Parallel Webpage Layout”, which implemented this simple model.

The problem with floats

Unfortunately, in the real world there is one significant complication: floats. Here’s an example of a document involving floats that illustrates the problem:

I shot the sheriff.

But I swear it was in self-defense.

I shot the sheriff.

And they say it is a capital offense.

I shot the sheriff

But I didn't shoot no deputy.

All around in my home town,

They're tryin' to track me down;

They say they want to bring me in guilty

For the killing of a deputy,

For the life of a deputy.

Rendered with a little extra formatting added, it looks like this:

The flow tree for this document might look like this:

Notice how the float in green (“I shot the sheriff…”) affects where the line breaks go in the two blocks to its left and below it (“I shot the sheriff…” and “All around…”). Line breaking is performed during the height assignment phase in Servo, because where the line breaks go determines the height of each flow.

This has important implications for the parallel algorithm described above. We don’t know how tall the float is until we’ve laid it out, and its height determines where to place the line breaks in the blocks next to it, so we have to lay out the float before laying out the blocks next to it. This means that we have to lay out the float before laying out any blocks that it’s adjacent to. But, more subtly, floats prevent us from laying out all the blocks that they impact in parallel as well. The reason is that we don’t know how many floats “stick out” of a block until we know its height, and in order to perform line breaking for a block we have to know how many floats “stuck out” of all the blocks before it. Consider the difference between the preceding document and this one:

The only difference between the first document and the this one is that the first unfloated block (“I shot the sheriff…”) is taller. But this impacts the height of the second block (“All around…”), by affecting where the lines get broken. So the key thing to note here is that, in general, floats force us to sequentialize the processing of the blocks next to them.

The way this was implemented in Servo before my pull requests is that any floats in the document caused all unfloated blocks to be laid out sequentially. (The floats themselves could still be laid out in parallel, but all other blocks in the page were laid out in order.) Unsurprisingly, this caused our parallel gains to evaporate on most real-world Web pages. The vast majority of modern Web pages do use floats in some capacity, as they’re one of the most popular ways to create typical layouts. So losing our parallel gains is quite unfortunate.

Can we do better? It turns out we can.

Clearing floats

As most designers know, the float property comes with a very useful companion property: clear. The clear property causes blocks to be shifted down in order to avoid impacting floats in one or both directions. For example, the document above with clear: right added to the second block looks like this:

This property is widely used on the Web to control where floats can appear, and we can take advantage of this to gain back parallelism. If we know that no floats can impact a block due to the use of the clear property, then we can lay it out in parallel with the blocks before it. In the document above, the second block (“All around…”) can be laid out at the same time as the float and the first block.

My second pull request implements this optimization in this way: During flow construction, which is a bottom-up traversal, we keep track of a flag, has_floated_descendants, and set it on each flow if it or any of its descendants are FloatFlow instances. (Actually, there are two such flags—has_left_floated_descendants and has_right_floated_descendants—but for the purposes of this explanation I’ll just treat it as one flag.) During width computation, we iterate over our children and set two flags: impacted_by_floats. (Again, there are actually two such flags—impacted_by_left_floats and impacted_by_right_floats.) impacted_by_floats is true for a flow if and only if any of the following is true:

The parent flow is impacted by floats.

The flow has floated descendants.

Any previous sibling flow is impacted by floats, unless the appropriate

clearproperty has been set between this flow and that sibling.

Only subtrees that have impacted_by_floats set to true are laid out sequentially, in order. The remaining subtrees can be laid out in parallel.

With this optimization implemented, documents above can be laid out in parallel as much as possible. It helps many real-world Web pages, as clear is a very commonly-used property.

At this point, two questions arise: “Can we do even more?” and “Is this algorithm enough to properly handle CSS?” As you might expect, the answer to the first is “yes”, and the answer to the second is “no”. To understand why, we need dive into the world of block formatting contexts.

Block formatting contexts

The behavior of overflow: hidden is subtle. Consider this document, which is identical to the document we’ve been using but with overflow: hidden specified on the blocks adjacent to the float:

I shot the sheriff.

But I swear it was in self-defense.

I shot the sheriff.

And they say it is a capital offense.

Rendered, it looks like this:

Notice that, with overflow: hidden specified, the float makes the entire width of the block next to it smaller: all the lines have been wrapped, not just those that impact the float.

What’s going on here is that overflow: hidden establishes what’s known as a block formatting context in CSS jargon. In Servo, block formatting contexts make our layout algorithm significantly more complex, because they require width assignment and height assignment to be intertwined, and for height assignment to be interruptible. To see why this is, recall that the flow tree for this document looks like this:

Remember that Servo’s layout algorithm performs width calculation top-down, then height calculation bottom-up—this works under the assumption that widths never depend on heights. But with block formatting contexts adjacent to floats, this is no longer true: the width of a block formatting context depends on the height of floats next to it. This is because we don’t know whether a float, such as the green float above, is tall enough to impact a block formatting context, like those that the “I shot the sheriff…” and “All around…” above establish, until we lay out all blocks prior to the context and the float itself. And without knowing that, we cannot assign the width of the block formatting contexts.

To handle this case, my patches change Servo’s layout in several ways:

When we see a block formatting context during width calculation, we check the value of the

impacted_by_floatsflag. If it is on, then we don’t calculate widths for that flow or any of its descendants. Instead, we set a flag calledwidth_assignment_delayed.When we encounter a block formatting context child of a flow while calculating heights, if that block formatting context has the flag

width_assignment_delayedset, we suspend the calculation of heights for that node, calculate the width of the block formatting context, and begin calculating widths and heights for that node and all of its descendants (in parallel, if possible).After calculating the height of a block formatting context, we resume calculation of heights for its parent.

Let’s look at the precise series of steps that we’ll follow for the document above:

Calculate the width of the root flow.

Calculate the width of the float flow.

Don’t calculate the widths of the two block flows; instead, set the

width_assignment_delayedflag.Calculate the width of the float flow’s inline flow child. The main width assignment phase is now complete.

Begin height calculation. First, calculate the height of the float flow and its inline child.

Start calculating the height of the root flow by placing the float.

We see that we’ve hit a block formatting context that has its width assignment delayed, so we clear that flag, determine its width, and start width calculation for its descendants.

Calculate width for the block flow’s inline child. Now width calculation is done for that subtree.

Calculate the height of the block flow’s inline child, and the block flow itself. Now height calculation is done for this subtree.

Resume calculating the height of the root flow. We see that the next block formatting context has its width assignment delayed, so we assign its width and repeat steps 8 and 9.

We’ve now calculated the height of the root flow, so we’re done.

Now this particular page didn’t result in any parallel speedups. However, block formatting contexts can result in additional parallelism in some cases. For example, consider this document:

Deals in your area:

Rendered, it looks like this:

- Buy 1 lawyer, get 1 free

- Free dental fillings

In this document, after we’ve laid out the sidebar, we can continue on and lay out the main part of the page entirely in parallel. We can lay out the block “Deals in your area” in parallel with the two list items “Buy 1…” and “Free dental fillings”. It turns out that this pattern is an extremely common way to create sidebars in real Web pages, so the ability to lay out the insides of block formatting contexts in parallel is a crucial optimization in practice. The upshot of all this is that block formatting contexts are a double-edged sword: they add an unfortunate dependency between heights and widths, but they enable us to recover parallelism even when blocks are impacted by floats, since we can lay out their interior in parallel.

Conclusion

No doubt about it, CSS 2.1 is tricky—floats perhaps more than anything else. But in spite of their difficulties, we’re finding that there are unexpected places where we can take advantage of parallelism to make a faster engine. I’m cautiously optimistic that Servo’s approaching the right design here—not only to make new content faster but also to accelerate the old.

http://pcwalton.github.com/blog/2014/02/25/revamped-parallel-layout-in-servo/

|

|

Fr'ed'eric Wang: TeXZilla 0.9.4 Released |

Introduction

For the past two months, the Mozilla MathML team has been working on TeXZilla, yet another LaTeX-to-MathML converter. The idea was to rely on itex2MML (which dates back from the beginning of the Mozilla MathML project) to create a LaTeX parser such that:

- It is compatible with the itex2MML syntax and is similarly generated from a LALR(1) grammar (the goal is only to support a restricted set of core LaTeX commands for mathematics, for a more complete converter of LaTeX documents see LaTeXML).

- It is available as a standalone Javascript module usable in all the Mozilla Web applications and add-ons (of course, it will work in non-Mozilla products too).

- It accepts any Unicode characters and supports right-to-left mathematical notation (these are important for the world-wide aspect of the Mozilla community).

The parser is generated with the help of

Jison and relies on a

grammar based on the one of itex2MML and on the

unicode.xml file of the

XML Entity Definitions

for Characters specification. As suggested by the version number,

this is still

in development. However, we have made enough progress to

present interesting features here and get more

users and developers involved.

Quick Examples

\frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1

http://www.maths-informatique-jeux.com/blog/frederic/?post/2014/02/25/TeXZilla-0.9.4-Released

|

|

Niko Matsakis: Rust RFC: Stronger guarantees for mutable borrows |

Today, if you do a mutable borrow of a local variable, you lose the ability to write to that variable except through the new reference you just created:

let mut x = 3;

let p = &mut x;

x += 1; // Error

*p += 1; // OK

However, you retain the ability to read the original variable:

let mut x = 3;

let p = &mut x;

print(x); // OK

print(*p); // OK

I would like to change the borrow checker rules so that both writes

and reads through the original path x are illegal while x is

mutably borrowed. This change is not motivated by soundness, as I

believe the current rules are sound. Rather, the motivation is that

this change gives strong guarantees to the holder of an &mut

pointer: at present, they can assume that an &mut referent will not

be changed by anyone else. With this change, they can also assume

that an &mut referent will not be read by anyone else. This enable

more flexible borrowing rules and a more flexible kind of data

parallelism API than what is possible today. It may also help to

create more flexible rules around moves of borrowed data. As a side

benefit, I personally think it also makes the borrow checker rules

more consistent (mutable borrows mean original value is not usable

during the mutable borrow, end of story). Let me lead with the

motivation.

Brief overview of my previous data-parallelism proposal

In a previous post I outlined a plan for data parallelism in Rust based on closure bounds. The rough idea is to leverage the checks that the borrow checker already does for segregating state into mutable-and-non-aliasable and immutable-but-aliasable. This is not only the recipe for creating memory safe programs, but it is also the recipe for data-race freedom: we can permit data to be shared between tasks, so long as it is immutable.

The API that I outlined in that previous post was based on a fork_join

function that took an array of closures. You would use it like this:

fn sum(x: &[int]) {

if x.len() == 0 {

return 0;

}

let mid = x.len() / 2;

let mut left = 0;

let mut right = 0;

fork_join([

|| left = sum(x.slice(0, mid)),

|| right = sum(x.slice(mid, x.len())),

]);

return left + right;

}

The idea of fork_join was that it would (potentially) fork into N

threads, one for each closure, and execute them in parallel. These

closures may access and even mutate state from the containing scope –

the normal borrow checker rules will ensure that, if one closure

mutates a variable, the other closures cannot read or write it. In

this example, that means that the first closure can mutate left so

long as the second closure doesn’t touch it (and vice versa for

right). Note that both closures share access to x, and this is

fine because x is immutable.

This kind of API isn’t safe for all data though. There are things that

cannot be shared in this way. One example is Cell, which is Rust’s

way of cheating the mutability rules and making a value that is

always mutable. If we permitted two threads to touch the same

Cell, they could both try to read and write it and, since Cell

does not employ locks, this would not be race free.

To avoid these sorts of cases, the closures that you pass to to

fork_join would be bounded by the builtin trait Share. As I

wrote in issue 11781, the trait Share indicates data that

is threadsafe when accessed through an &T reference (i.e., when

aliased).

Most data is sharable (let T stand for some other sharable type):

- POD (plain old data) types are forkable, so things like

intetc. &Tand&mut T, because both are immutable when aliased.~Tis sharable, because is is not aliasable.- Structs and enums that are composed of sharable data are sharable.

ARC, because the reference count is maintained atomically.- The various thread-safe atomic integer intrinsics and so on.

Things which are not sharable include:

- Many types that are unsafely implemented:

CellandRefCell, which have non-atomic interior mutabilityRc, which uses non-atomic reference counting

- Managed data (

Gc) because we do not wish to maintain or support a cross-thread garbage collector

There is a wrinkle though. With the current borrow checker rules, forkable data is only safe to access from a parallel thread if the main thread is suspended. Put another way, forkable closures can only run concurrently with other forkable closures, but not with the parent, which might not be a forkable thing.

This is reflected in the API, which consisted of a function

fork_join function that both spawned the threads and joined them.

The natural semantics of a function call would thus cause the parent

to block while the threads executed. For many use cases, this is just

fine, but there are other cases where it’s nice to be able to fork off

threads continuously, allowing the parent to keep running in the

meantime.

Note: This is a refinement of the previous proposal, which was more complex. The version presented here is simpler but equally expressive. It will work best when combined with my (ill documented, that’s coming) plans for unboxed closures, which are required to support convenient array map operations and so forth.

A more flexible proposal

If we made the change that I described above – that is, we prohibit

reads of data that is mutably borrowed – then we could adjust the

fork_join API to be more flexible. In particular, we could support

an API like the following:

fn sum(x: &[int]) {

if x.len() == 0 {

return 0;

}

let mid = x.len() / 2;

let mut left = 0;

let mut right = 0;

fork_join_section(|sched| {

sched.fork(|| left = sum(x.slice(0, mid)));

sched.fork(|| right = sum(x.slice(mid, x.len())));

});

return left + right;

}

The idea here is that we replaced the fork_join() call with a call

to fork_join_section(). This function takes a closure argument and

passes it a an argument sched – a scheduler. The scheduler offers a

method fork that can be invoked to fork off a potentially parallel

task. This task may begin execution immediately and will be joined

once the fork_join_section ends.

In some sense this is just a more verbose replacement for the previous

call, and I imagine that the fork_join() function I showed

originally will remain as a convenience function. But in another sense

this new version is much more flexible – it can be used to fork off

any number of tasks, for example, and it permits the main thread to

continue executing while the fork runs.

An aside: it should be noted that this API also opens the door (wider) to a kind of anti-pattern, in which the main thread quickly enqueues a ton of small tasks before it begins to operate on them. This is the opposite of what (e.g.) Cilk would do. In Cilk, the processor would immediately begin executing the forked task, leaving the rest of the “forking” in a stealable thunk. If you’re lucky, some other proc will come along and do the forking for you. This can reduce overall overhead. But anyway, this is fairly orthogonal.

Beyond parallelism

The stronger guarantee concerning &mut will be useful in other

scenarios. One example that comes to mind are moves: for example,

today we do not permit moves out of borrowed data. In principle,

though, we should be able to permit moves out of &mut data, so long

as the value is replaced before anyone can read it.

Without the rule I am proposing here, though, it’s really hard to prevent reads at all without tracking what pointers point at (which we do not do nor want to do, generally). Consider even a simple program like the following:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

I don’t want to dive into the details of moves here, because permitting rules from borrowed pointers is a complex topic of its own (we must consider, for example, failure and what happens when destructors run). But without the proposal here, I think we can’t even get started.

Speaking more generally and mildly more theoretically, this rule helps

to align Rust logic with separation logic. Effectively, &mut

references are known to be separated from the rest of the heap. This is

similar to what research languages like Mezzo do. (By the way,

if you are not familiar with Mezzo, check it out. Awesome stuff.)

Impact on existing code

It’s hard to say what quantity of existing code relies on the current rules. My gut tells me “not much” but without implementing the change I can’t say for certain.

How to implement