Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

William Lachance: This week in Glean (special guest post): mozregression telemetry (part 1) |

(“This Week in Glean” is a series of blog posts that the Glean Team at Mozilla is using to try to communicate better about our work. They could be release notes, documentation, hopes, dreams, or whatever: so long as it is inspired by Glean. You can find an index of all TWiG posts online.)

This is a special guest post by non-Glean-team member William Lachance!

As I mentioned last time I talked about mozregression, I have been thinking about adding some telemetry to the system to better understand the usage of this tool, to justify some part of Mozilla spending some cycles maintaining and improving it (assuming my intuition that this tool is heavily used is confirmed).

Coincidentally, the Telemetry client team has been working on a new library for measuring these types of things in a principled way called Glean, which even has python bindings! Using this has the potential in saving a lot of work: not only does Glean provide a framework for submitting data, our backend systems are automatically set up to process data submitted via into Glean into BigQuery tables, which can then easily be queried using tools like sql.telemetry.mozilla.org.

I thought it might be useful to go through some of what I’ve been exploring, in case others at Mozilla are interested in instrumenting their pet internal tools or projects. If this effort is successful, I’ll distill these notes into a tutorial in the Glean documentation.

Initial steps: defining pings and metrics

The initial step in setting up a Glean project of any type is to define explicitly the types of pings and metrics. You can look at a “ping” as being a small bucket of data submitted by a piece of software in the field. A “metric” is something we’re measuring and including in a ping.

Most of the Glean documentation focuses on browser-based use-cases where we might want to sample lots of different things on an ongoing basis, but for mozregression our needs are considerably simpler: we just want to know when someone has used it along with a small number of non-personally identifiable characteristics of their usage, e.g. the mozregression version number and the name of the application they are bisecting.

Glean has the concept of event pings, but it seems like those are there more for a fine-grained view of what’s going on during an application’s use. So let’s define a new ping just for ourselves, giving it the unimaginative name “usage”. This goes in a file called pings.yaml:

---

$schema: moz://mozilla.org/schemas/glean/pings/1-0-0

usage:

description: >

A ping to record usage of mozregression

include_client_id: true

notification_emails:

- wlachance@mozilla.com

bugs:

- http://bugzilla.mozilla.org/123456789/

data_reviews:

- http://example.com/path/to/data-reviewWe also need to define a list of things we want to measure. To start with, let’s just test with one piece of sample information: the app we’re bisecting (e.g. “Firefox” or “Gecko View Example”). This goes in a file called metrics.yaml:

---

$schema: moz://mozilla.org/schemas/glean/metrics/1-0-0

usage:

app:

type: string

description: >

The name of the app being bisected

notification_emails:

- wlachance@mozilla.com

bugs:

- https://bugzilla.mozilla.org/show_bug.cgi?id=1581647

data_reviews:

- http://example.com/path/to/data-review

expires: never

send_in_pings:

- usageThe data_reviews sections in both of the above are obviously bogus, we will need to actually get data review before landing and using this code, to make sure that we’re in conformance with Mozilla’s data collection policies.

Testing it out

But in the mean time, we can test our setup with the Glean debug pings viewer by setting a special tag (mozregression-test-tag) on our output. Here’s a small python script which does just that:

from pathlib import Path

from glean import Glean, Configuration

from glean import (load_metrics,

load_pings)

mozregression_path = Path.home() / '.mozilla2' / 'mozregression'

Glean.initialize(

application_id="mozregression",

application_version="0.1.1",

upload_enabled=True,

configuration=Configuration(

ping_tag="mozregression-test-tag"

),

data_dir=mozregression_path / "data"

)

Glean.set_upload_enabled(True)

pings = load_pings("pings.yaml")

metrics = load_metrics("metrics.yaml")

metrics.usage.app.set("reality")

pings.usage.submit()Running this script on my laptop, I see that a respectable JSON payload was delivered to and processed by our servers:

As you can see, we’re successfully processing both the “version” number of mozregression, some characteristics of the machine sending the information (my MacBook in this case), as well as our single measure. We also have a client id, which should tell us roughly how many distinct installations of mozregression are sending pings. This should be more than sufficient for an initial “mozregression usage dashboard”.

Next steps

There are a bunch of things I still need to work through before landing this inside mozregression itself. Notably, the Glean python bindings are python3-only, so we’ll need to port the mozregression GUI to python 3 before we can start measuring usage there. But I’m excited at how quickly this work is coming together: stay tuned for part 2 in a few weeks.

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: Expect: tweaks in curl |

One of the persistent myths about HTTP is that it is “a simple protocol”.

Expect: – not always expected

One of the dusty spec corners of HTTP/1.1 (Section 5.1.1 of RFC 7231) explains how the Expect: header works. This is still today in 2020 one of the HTTP request headers that is very commonly ignored by servers and intermediaries.

Background

HTTP/1.1 is designed for being sent over TCP (and possibly also TLS) in a serial manner. Setting up a new connection is costly, both in terms of CPU but especially in time – requiring a number of round-trips. (I’ll detail further down how HTTP/2 fixes all these issues in a much better way.)

HTTP/1.1 provides a number of ways to allow it to perform all its duties without having to shut down the connection. One such an example is the ability to tell a client early on that it needs to provide authentication credentials before the clients sends of a large payload. In order to maintain the TCP connection, a client can’t stop sending a HTTP payload prematurely! When the request body has started to get transmitted, the only way to stop it before the end of data is to cut off the connection and create a new one – wasting time and CPU…

“We want a 100 to continue”

A client can include a header in its outgoing request to ask the server to first acknowledge that everything is fine and that it can continue to send the “payload” – or it can return status codes that informs the client that there are other things it needs to fulfill in order to have the request succeed. Most such cases typically that involves authentication.

This “first tell me it’s OK to send it before I send it” request header looks like this:

Expect: 100-continue

Servers

Since this mandatory header is widely not understood or simply ignored by HTTP/1.1 servers, clients that issue this header will have a rather short timeout and if no response has been received within that period it will proceed and send the data even without a 100.

The timeout thing is happening so often that removing the Expect: header from curl requests is a very common answer to question on how to improve POST or PUT requests with curl, when it works against such non-compliant servers.

Popular browsers

Browsers are widely popular HTTP clients but none of the popular ones ever use this. In fact, very few clients do. This is of course a chicken and egg problem because servers don’t support it very well because clients don’t and client’s don’t because servers don’t support it very well…

curl sends Expect:

When we implemented support for HTTP/1.1 in curl back in 2001, we wanted it done proper. We made it have a short, 1000 milliseconds, timeout waiting for the 100 response. We also made curl automatically include the Expect: header in outgoing requests if we know that the body is larger than NNN or we don’t know the size at all before-hand (and obviously, we don’t do it if we send the request chunked-encoded).

The logic being there that if the data amount is smaller than NNN, then the waste is not very big and we can just as well send it (even if we risk sending it twice) as waiting for a response etc is just going to be more time consuming.

That NNN margin value (known in the curl sources as the EXPECT_100_THRESHOLD) in curl was set to 1024 bytes already then back in the early 2000s.

Bumping EXPECT_100_THRESHOLD

Starting in curl 7.69.0 (due to ship on March 4, 2020) we catch up a little with the world around us and now libcurl will only automatically set the Expect: header if the amount of data to send in the body is larger than 1 megabyte. Yes, we raise the limit by 1024 times.

The reasoning is of course that for most Internet users these days, data sizes below a certain size isn’t even noticeable when transferred and so we adapt. We then also reduce the amount of problems for the very small data amounts where waiting for the 100 continue response is a waste of time anyway.

Credits: landed in this commit. (sorry but my WordPress stupidly can’t show the proper Asian name of the author!)

417 Expectation Failed

One of the ways that a HTTP/1.1 server can deal with an Expect: 100-continue header in a request, is to respond with a 417 code, which should tell the client to retry the same request again, only without the Expect: header.

While this response is fairly uncommon among servers, curl users who ran into 417 responses have previously had to resort to removing the Expect: header “manually” from the request for such requests. This was of course often far from intuitive or easy to figure out for users. A source for grief and agony.

Until this commit, also targeted for inclusion in curl 7.69.0 (March 4, 2020). Starting now, curl will automatically act on 417 response if it arrives as a consequence of using Expect: and then retry the request again without using the header!

Credits: I wrote the patch.

HTTP/2 avoids this all together

With HTTP/2 (and HTTP/3) this entire thing is a non-issue because with these modern protocol versions we can abort a request (stop a stream) prematurely without having to sacrifice the connection. There’s therefore no need for this crazy dance anymore!

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2020/02/27/expect-tweaks-in-curl/

|

|

The Rust Programming Language Blog: Announcing Rust 1.41.1 |

The Rust team has published a new point release of Rust, 1.41.1. Rust is a programming language that is empowering everyone to build reliable and efficient software.

If you have a previous version of Rust installed via rustup, getting Rust 1.41.1 is as easy as:

rustup update stable

If you don't have it already, you can get rustup from the appropriate page on our website.

What's in 1.41.1 stable

Rust 1.41.1 addresses two critical regressions introduced in Rust 1.41.0:

a soundness hole related to static lifetimes, and a miscompilation causing segfaults.

These regressions do not affect earlier releases of Rust,

and we recommend users of Rust 1.41.0 to upgrade as soon as possible.

Another issue related to interactions between 'static and Copy implementations,

dating back to Rust 1.0, was also addressed by this release.

A soundness hole in checking static items

In Rust 1.41.0, due to some changes in the internal representation of static values,

the borrow checker accidentally allowed some unsound programs.

Specifically, the borrow checker would not check that static items had the correct type.

This in turn would allow the assignment of a temporary,

with a lifetime less than 'static, to a static variable:

static mut MY_STATIC: &'static u8 = &0;

fn main() {

let my_temporary = 42;

unsafe {

// Erroneously allowed in 1.41.0:

MY_STATIC = &my_temporary;

}

}

This was addressed in 1.41.1, with the program failing to compile:

error[E0597]: `my_temporary` does not live long enough

--> src/main.rs:6:21

|

6 | MY_STATIC = &my_temporary;

| ------------^^^^^^^^^^^^^

| | |

| | borrowed value does not live long enough

| assignment requires that `my_temporary` is borrowed for `'static`

7 | }

8 | }

| - `my_temporary` dropped here while still borrowed

You can learn more about this bug in issue #69114 and the PR that fixed it.

Respecting a 'static lifetime in a Copy implementation

Ever since Rust 1.0, the following erroneous program has been compiling:

#[derive(Clone)]

struct Foo<'a>(&'a u32);

impl Copy for Foo<'static> {}

fn main() {

let temporary = 2;

let foo = (Foo(&temporary),);

drop(foo.0); // Accessing a part of `foo` is necessary.

drop(foo.0); // Indexing an array would also work.

}

In Rust 1.41.1, this issue was fixed by the same PR as the one above. Compiling the program now produces the following error:

error[E0597]: `temporary` does not live long enough

--> src/main.rs:7:20

|

7 | let foo = (Foo(&temporary),);

| ^^^^^^^^^^ borrowed value does not live long enough

8 | drop(foo.0);

| ----- copying this value requires that

| `temporary` is borrowed for `'static`

9 | drop(foo.0);

10 | }

| - `temporary` dropped here while still borrowed

This error occurs because Foo<'a>, for some 'a, only implements Copy when 'a: 'static.

However, the temporary variable,

with some lifetime '0 does not outlive 'static and hence Foo<'0> is not Copy,

so using drop the second time around should be an error.

Miscompiled bound checks leading to segfaults

In a few cases, programs compiled with Rust 1.41.0 were omitting bound checks in the memory allocation code. This caused segfaults if out of bound values were provided. The root cause of the miscompilation was a change in a LLVM optimization pass, introduced in LLVM 9 and reverted in LLVM 10.

Rust 1.41.0 uses a snapshot of LLVM 9, so we cherry-picked the revert into Rust 1.41.1, addressing the miscompilation. You can learn more about this bug in issue #69225.

Contributors to 1.41.1

Many people came together to create Rust 1.41.1. We couldn't have done it without all of you. Thanks!

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: curl ootw: –ftp-pasv |

(previous options of the week)

--ftp-pasv has no short version of the option.

This option was added in curl 7.11.0, January 2004.

FTP uses dual connections

FTP is a really old protocol with traces back to the early 1970s, actually from before we even had TCP. It truly comes from a different Internet era.

When a client speaks FTP, it first sets up a control connection to the server, issues commands to it that instructs it what to do and then when it wants to transfer data, in either direction, a separate data connection is required; a second TCP connection in addition to the initial one.

This second connection can be setup two different ways. The client instructs the server which way to use:

- the client connects again to the server (passive)

- the server connects back to the client (active)

Passive please

--ftp-pasv is the default behavior of curl and asks to do the FTP transfer in passive mode. As this is the default, you will rarely see this option used. You could for example use it in cases where you set active mode in your .curlrc file but want to override that decision for a single specific invocation.

The opposite behavior, active connection, is called for with the --ftp-port option. An active connection asks the server to do a TCP connection back to the client, an action that these days is rarely functional due to firewall and network setups etc.

FTP passive behavior detailed

FTP was created decades before IPv6 was even thought of, so the original FTP spec assumes and uses IPv4 addresses in several important places, including how to ask the server for setting up a passive data transfer.

EPSV is the “new” FTP command that was introduced to enable FTP over IPv6. I call it new because it wasn’t present in the original RFC 959 that otherwise dictates most of how FTP works. EPSV is an extension.

EPSV was for a long time only supported by a small fraction of FTP servers and it probably still exists such servers, so in case invoking this command is a problem, curl needs to fallback to the original command for this purpose: PASV.

curl first tries EPSV and if that fails, it sends PASV. The first of those commands that is accepted by the server will make the server wait for the client to connect to it (again) on fresh new TCP port number.

Problems with the dual connections

Your firewall needs to allow your client to connect to the new port number the server opened up for the data connection. This is particularly complicated if you enable FTPS (encrypted FTP) as then the new port number is invisible to middle-boxes such as firewalls.

Dual connections also often cause problems because the control connection will be idle during the transfer and that idle connection sometimes get killed by NATs or other middle-boxes due to that inactivity.

Enabling active mode is usually even worse than passive mode in modern network setups, as then the firewall needs to allow an outside TCP connection to come in and connect to the client on a given port number.

Example

Ask for a file using passive FTP mode:

curl --ftp-pasv ftp://ftp.example.com/cake-recipe.txt

Related options

--disable-epsv will prevent curl from using the EPSV command – which then also makes this transfer not work for IPv6. --ftp-port switches curl to active connection.

--ftp-skip-pasv-ip tells curl that the IP address in the server’s PASV response should be ignored and the IP address of the control connection should instead be used when the second connection is setup.

|

|

Chris H-C: Jira, Bugzilla, and Tales of Issue Trackers Past |

It seems as though Mozilla is never not in a period of transition. The distributed nature of the organization and community means that teams and offices and any informal or formal group is its own tiny experimental plot tended by gardeners with radically different tastes.

And if there’s one thing that unites gardeners and tech workers is that both have Feelings about their tools.

Tools are personal things: they’re the only thing that allows us to express ourselves in our craft. I can’t code without an editor. I can’t prune without shears. They’re the part of our work that we actually touch. The code lives Out There, the garden is Outside… but the tools are in our hands.

But tools can also be group things. A shed is a tool for everyone’s tools. A workshop is a tool that others share. An Issue Tracker is a tool that helps us all coordinate work.

And group things require cooperation, agreement, and compromise.

While I was on the Browser team at BlackBerry I used a variety of different Issue Trackers. We started with an outdated version of FogBugz, then we had a Bugzilla fork for the WebKit porting work and MKS Integrity for everything else across the entire company, and then we all standardized on Jira.

With minimal customization, Jira and MKS Integrity both seemed to be perfectly adequate Issue Tracking Software. They had id numbers, relationships, state, attachments, comments… all the things you need in an Issue Tracker. But they couldn’t just be “perfectly adequate”, they had to be better enough than what they were replacing to warrant the switch.

In other words, to make the switch the new thing needs to do something that the previous one couldn’t, wouldn’t, or just didn’t do (or you’ve forgotten that it did). And every time Jira or MKS is customized it seems to stop being Issue Tracking Software and start being Workflow Management Software.

Perhaps because the people in charge of the customization are interested more in workflows than in Issue Tracking?

Regardless of why, once they become Workflow Management Software they become incomparable with Issue Trackers. Apples and Oranges. You end up optimizing for similar but distinct use cases as it might become more important to report about issues than it is to file and fix and close them.

And that’s the state Mozilla might be finding itself in right now as a few teams here and there try to find the best tools for their garden and settle upon Jira. Maybe they tried building workflows in Bugzilla and didn’t make it work. Maybe they were using Github Issues for a while and found it lacking. We already had multiple places to file issues, but now some of the places are Workflow Management Software.

And the rumbling has begun. And it’s no wonder, as even tools that are group things are still personal. They’re still what we touch when we craft.

The GNU-minded part of me thinks that workflow management should be built above and separate from issue tracking by the skillful use of open and performant interfaces. Bugzilla lets you query whatever you want, however you want, so why not build reporting Over There and leave me my issue tracking Here where I Like It.

The practical-minded part of me thinks that it doesn’t matter what we choose, so long as we do it deliberately and consistently.

The schedule-minded part of me notices that I should probably be filing and fixing issues rather than writing on them. And I think now’s the time to let that part win.

:chutten

https://chuttenblog.wordpress.com/2020/02/25/jira-bugzilla-and-tales-of-issue-trackers-past/

|

|

Hacks.Mozilla.Org: Securing Firefox with WebAssembly |

Protecting the security and privacy of individuals is a central tenet of Mozilla’s mission, and so we constantly endeavor to make our users safer online. With a complex and highly-optimized system like Firefox, memory safety is one of the biggest security challenges. Firefox is mostly written in C and C++. These languages are notoriously difficult to use safely, since any mistake can lead to complete compromise of the program. We work hard to find and eliminate memory hazards, but we’re also evolving the Firefox codebase to address these attack vectors at a deeper level. Thus far, we’ve focused primarily on two techniques:

- Breaking code into multiple sandboxed processes with reduced privileges

- Rewriting code in a safe language like Rust

A new approach

While we continue to make extensive use of both sandboxing and Rust in Firefox, each has its limitations. Process-level sandboxing works well for large, pre-existing components, but consumes substantial system resources and thus must be used sparingly. Rust is lightweight, but rewriting millions of lines of existing C++ code is a labor-intensive process.

Consider the Graphite font shaping library, which Firefox uses to correctly render certain complex fonts. It’s too small to put in its own process. And yet, if a memory hazard were uncovered, even a site-isolated process architecture wouldn’t prevent a malicious font from compromising the page that loaded it. At the same time, rewriting and maintaining this kind of domain-specialized code is not an ideal use of our limited engineering resources.

So today, we’re adding a third approach to our arsenal. RLBox, a new sandboxing technology developed by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, the University of Texas, Austin, and Stanford University, allows us to quickly and efficiently convert existing Firefox components to run inside a WebAssembly sandbox. Thanks to the tireless efforts of Shravan Narayan, Deian Stefan, Tal Garfinkel, and Hovav Shacham, we’ve successfully integrated this technology into our codebase and used it to sandbox Graphite.

This isolation will ship to Linux users in Firefox 74 and to Mac users in Firefox 75, with Windows support following soon after. You can read more about this work in the press releases from UCSD and UT Austin along with the joint research paper. Read on for a technical overview of how we integrated it into Firefox.

Building a wasm sandbox

The core implementation idea behind wasm sandboxing is that you can compile C/C++ into wasm code, and then you can compile that wasm code into native code for the machine your program actually runs on. These steps are similar to what you’d do to run C/C++ applications in the browser, but we’re performing the wasm to native code translation ahead of time, when Firefox itself is built. Each of these two steps rely on significant pieces of software in their own right, and we add a third step to make the sandboxing conversion more straightforward and less error prone.

First, you need to be able to compile C/C++ into wasm code. As part of the WebAssembly effort, a wasm backend was added to Clang and LLVM. Having a compiler is not enough, though; you also need a standard library for C/C++. This component is provided via wasi-sdk. With those pieces, we have enough to translate C/C++ into wasm code.

Second, you need to be able to convert the wasm code into native object files. When we first started implementing wasm sandboxing, we were often asked, “why do you even need this step? You could distribute the wasm code and compile it on-the-fly on the user’s machine when Firefox starts.” We could have done that, but that method requires the wasm code to be freshly compiled for every sandbox instance. Per-sandbox compiled code is unnecessary duplication in a world where every origin resides in a separate process. Our chosen approach enables sharing compiled native code between multiple processes, resulting in significant memory savings. This approach also improves the startup speed of the sandbox, which is important for fine-grained sandboxing, e.g. sandboxing the code associated with every font accessed or image loaded.

Ahead-of-time compilation with Cranelift and friends

This approach does not imply that we have to write our own wasm to native code compiler! We implemented this ahead-of-time compilation using the same compiler backend that will eventually power the wasm component of Firefox’s JavaScript engine: Cranelift, via the Bytecode Alliance’s Lucet compiler and runtime. This code sharing ensures that improvements benefit both our JavaScript engine and our wasm sandboxing compiler. These two pieces of code currently use different versions of Cranelift for engineering reasons. As our sandboxing technology matures, however, we expect to modify them to use the exact same codebase.

Now that we’ve translated the wasm code into native object code, we need to be able to call into that sandboxed code from C++. If the sandboxed code was running in a separate virtual machine, this step would involve looking up function names at runtime and managing state associated with the virtual machine. With the setup above, however, sandboxed code is native compiled code that respects the wasm security model. Therefore, sandboxed functions can be called using the same mechanisms as calling regular native code. We have to take some care to respect the different machine models involved: wasm code uses 32-bit pointers, whereas our initial target platform, x86-64 Linux, uses 64-bit pointers. But there are other hurdles to overcome, which leads us to the final step of the conversion process.

Getting sandboxing correct

Calling sandboxed code with the same mechanisms as regular native code is convenient, but it hides an important detail. We cannot trust anything coming out of the sandbox, as an adversary may have compromised the sandbox.

For instance, for a sandboxed function:

/* Returns values between zero and sixteen. */

int return_the_value();We cannot guarantee that this sandboxed function follows its contract. Therefore, we need to ensure that the returned value falls in the range that we expect.

Similarly, for a sandboxed function returning a pointer:

extern const char* do_the_thing();We cannot guarantee that the returned pointer actually points to memory controlled by the sandbox. An adversary may have forced the returned pointer to point somewhere in the application outside of the sandbox. Therefore, we validate the pointer before using it.

There are additional runtime constraints that are not obvious from reading the source. For instance, the pointer returned above may point to dynamically allocated memory from the sandbox. In that case, the pointer should be freed by the sandbox, not by the host application. We could rely on developers to always remember which values are application values and which values are sandbox values. Experience has shown that approach is not feasible.

Tainted data

The above two examples point to a general principle: data returned from the sandbox should be specifically identified as such. With this identification in hand, we can ensure the data is handled in appropriate ways.

We label data associated with the sandbox as “tainted”. Tainted data can be freely manipulated (e.g. pointer arithmetic, accessing fields) to produce more tainted data. But when we convert tainted data to non-tainted data, we want those operations to be as explicit as possible. Taintedness is valuable not just for managing memory returned from the sandbox. It’s also valuable for identifying data returned from the sandbox that may need additional verification, e.g. indices pointing into some external array.

We therefore model all exposed functions from the sandbox as returning tainted data. Such functions also take tainted data as arguments, because anything they manipulate must belong to the sandbox in some way. Once function calls have this interface, the compiler becomes a taintedness checker. Compiler errors will occur when tainted data is used in contexts that want untainted data, or vice versa. These contexts are precisely the places where tainted data needs to be propagated and/or data needs to be validated. RLBox handles all the details of tainted data and provides features that make incremental conversion of a library’s interface to a sandboxed interface straightforward.

Next Steps

With the core infrastructure for wasm sandboxing in place, we can focus on increasing its impact across the Firefox codebase – both by bringing it to all of our supported platforms, and by applying it to more components. Since this technique is lightweight and easy to use, we expect to make rapid progress sandboxing more parts of Firefox in the coming months. We’re focusing our initial efforts on third-party libraries bundled with Firefox. Such libraries generally have well-defined entry points and don’t pervasively share memory with the rest of the system. In the future, however, we also plan to apply this technology to first-party code.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful for the work of our research partners at UCSD, UT Austin, and Stanford, who were the driving force behind this effort. We’d also like to extend a special thanks to our partners at the Bytecode Alliance – particularly the engineering team at Fastly, who developed Lucet and helped us extend its capabilities to make this project possible.

The post Securing Firefox with WebAssembly appeared first on Mozilla Hacks - the Web developer blog.

https://hacks.mozilla.org/2020/02/securing-firefox-with-webassembly/

|

|

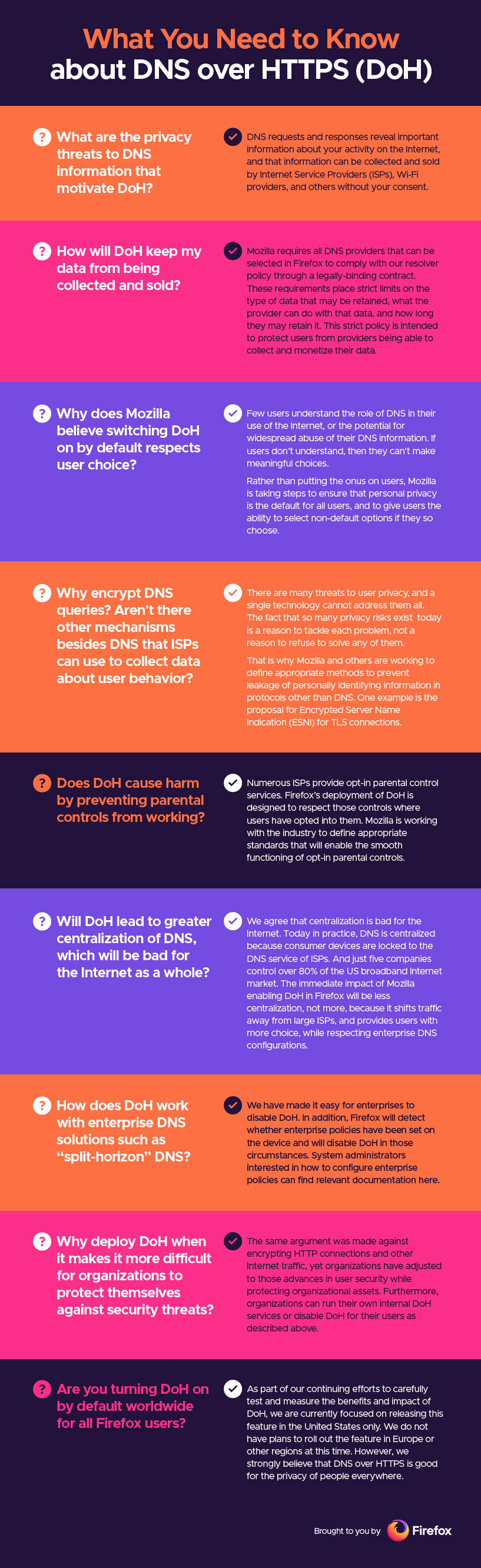

Mozilla Open Policy & Advocacy Blog: The Facts: Mozilla’s DNS over HTTPs (DoH) |

The current insecure DNS system leaves billions of people around the world vulnerable because the data about where they go on the internet is unencrypted. We’ve set out to change that. In 2017, Mozilla began working on the DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) protocol to close this privacy gap within the web’s infrastructure. Today, Firefox is enabling encrypted DNS over HTTPS by default in the US giving our users more privacy protection wherever and whenever they’re online.

DoH will encrypt DNS traffic from clients (browsers) to resolvers through HTTPS so that users’ web browsing can’t be intercepted or tampered with by someone spying on the network. The resolvers we’ve chosen to work with so far – Cloudflare and NextDNS – have agreed to be part of our Trusted Recursive Resolver program. The program places strong policy requirements on the resolvers and how they handle data. This includes placing strict limits on data retention so providers- including internet service providers – can no longer tap into an unprotected stream of a user’s browsing history to build a profile that can be sold, or otherwise used in ways that people have not meaningfully consented to. We hope to bring more partners into the TRR program.

Like most new technologies on the web, there has been a healthy conversation about this new protocol. We’ve seen non-partisan input, privacy experts, and other organizations all weigh in. And because we value transparency and open dialogue this conversation has helped inform our plans for DoH. We are confident that the research and testing we’ve done over the last two years has ensured our roll-out of DoH respects user privacy and makes the web safer for everyone. Through DoH and our trusted recursive resolver program we can begin to close the data leaks that have been part of the domain name system since it was created 35 years ago.

Here are a few things we think are important to know about our deployment of DNS over HTTPs.

The post The Facts: Mozilla’s DNS over HTTPs (DoH) appeared first on Open Policy & Advocacy.

https://blog.mozilla.org/netpolicy/2020/02/25/the-facts-mozillas-dns-over-https-doh/

|

|

The Mozilla Blog: Firefox continues push to bring DNS over HTTPS by default for US users |

Today, Firefox began the rollout of encrypted DNS over HTTPS (DoH) by default for US-based users. The rollout will continue over the next few weeks to confirm no major issues are discovered as this new protocol is enabled for Firefox’s US-based users.

A little over two years ago, we began work to help update and secure one of the oldest parts of the internet, the Domain Name System (DNS). To put this change into context, we need to briefly describe how the system worked before DoH. DNS is a database that links a human-friendly name, such as www.mozilla.org, to a computer-friendly series of numbers, called an IP address (e.g. 192.0.2.1). By performing a “lookup” in this database, your web browser is able to find websites on your behalf. Because of how DNS was originally designed decades ago, browsers doing DNS lookups for websites — even encrypted https:// sites — had to perform these lookups without encryption. We described the impact of insecure DNS on our privacy:

Because there is no encryption, other devices along the way might collect (or even block or change) this data too. DNS lookups are sent to servers that can spy on your website browsing history without either informing you or publishing a policy about what they do with that information.

At the creation of the internet, these kinds of threats to people’s privacy and security were known, but not being exploited yet. Today, we know that unencrypted DNS is not only vulnerable to spying but is being exploited, and so we are helping the internet to make the shift to more secure alternatives. We do this by performing DNS lookups in an encrypted HTTPS connection. This helps hide your browsing history from attackers on the network, helps prevent data collection by third parties on the network that ties your computer to websites you visit.

Since our work on DoH began, many browsers have joined in announcing their plans to support DoH, and we’ve even seen major websites like Facebook move to support a more secure DNS.

If you’re interested in exactly how DoH protects your browsing history, here’s an in-depth explainer by Lin Clark.

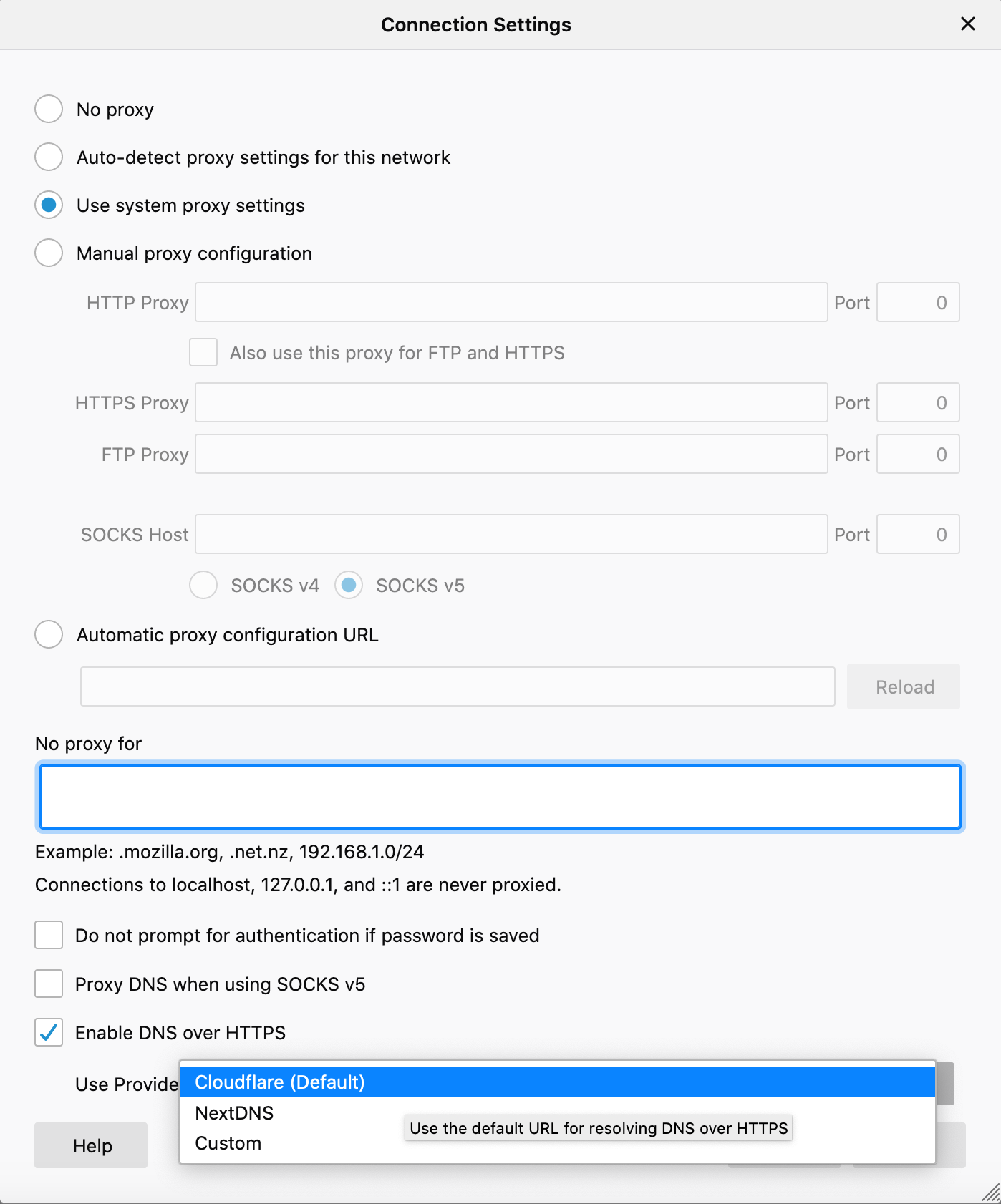

We’re enabling DoH by default only in the US. If you’re outside of the US and would like to enable DoH, you’re welcome to do so by going to Settings, then General, then scroll down to Networking Settings and click the Settings button on the right. Here you can enable DNS over HTTPS by clicking, and a checkbox will appear. By default, this change will send your encrypted DNS requests to Cloudflare.

Users have the option to choose between two providers — Cloudflare and NextDNS — both of which are trusted resolvers. Go to Settings, then General, then scroll down to Network Settings and click the Settings button on the right. From there, go to Enable DNS over HTTPS, then use the pull down menu to select the provider as your resolver.

Users can choose between two providers

We continue to explore enabling DoH in other regions, and are working to add more providers as trusted resolvers to our program. DoH is just one of the many privacy protections you can expect to see from us in 2020.

You can download the release here.

The post Firefox continues push to bring DNS over HTTPS by default for US users appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.

|

|

Wladimir Palant: McAfee WebAdvisor: From XSS in a sandboxed browser extension to administrator privileges |

A while back I wrote about a bunch of vulnerabilities in McAfee WebAdvisor, a component of McAfee antivirus products which is also available as a stand-alone application. Part of the fix was adding a bunch of pages to the extension which were previously hosted on siteadvisor.com, generally a good move. However, when I looked closely I noticed a Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability in one of these pages (CVE-2019-3670).

Now an XSS vulnerability in a browser extension is usually very hard to exploit thanks to security mechanisms like Content Security Policy and sandboxing. These mechanisms were intact for McAfee WebAdvisor and I didn’t manage to circumvent them. Yet I still ended up with a proof of concept that demonstrated how attackers could gain local administrator privileges through this vulnerability, something that came as a huge surprise to me as well.

Summary of the findings

Both the McAfee WebAdvisor browser extension and the HTML-based user interface of its UIHost.exe application use the jQuery library. This choice of technology proved quite fatal: not only did it contribute to both components being vulnerable to XSS, it also made the vulnerability exploitable in the browser extension where existing security mechanisms would normally make exploitation very difficult to say the least.

In the end, a potential attacker could go from a reflective XSS vulnerability in the extension to a persistent XSS vulnerability in the application to writing arbitrary Windows registry values. The latter can then be used to run any commands with privileges of the local system’s administrator. The attack could be performed by any website and the required user interaction would be two clicks anywhere on the page.

At the time of writing, McAfee closed the XSS vulnerability in the WebAdvisor browser extensions and users should update to version 8.0.0.37123 (Chrome) or 8.0.0.37627 (Firefox) ASAP. From the look of it, the XSS vulnerability in the WebAdvisor application remains unaddressed. The browser extensions no longer seem to have the capability to add whitelist entries here which gives it some protection for now. It should still be possible for malware running with user’s privileges to gain administrator access through it however.

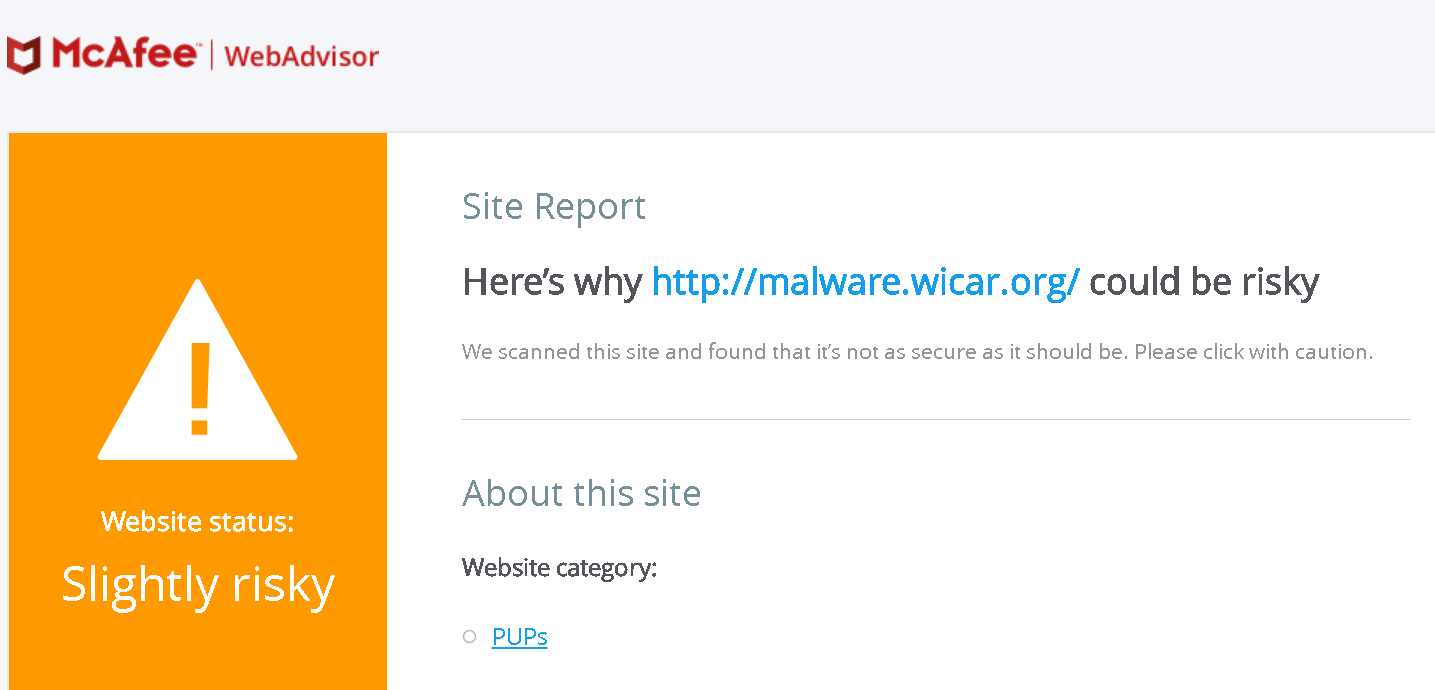

The initial vulnerability

When McAfee WebAdvisor prevents you from accessing a malicious page, a placeholder page is displayed instead. It contains a “View site report” link which brings you to the detailed information about the site. Here is what this site report looks like for the test website malware.wicar.org:

This page happens to be listed in the extensions web accessible resources, meaning that any website can open it with any parameters. And the way it handles the url query parameter is clearly problematic. The following code has been paraphrased to make it more readable:

const url = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search).get("url");

const uri = getURI(url);

const text = localeData(`site_report_main_url_${state}`, [`${uri}`]);

$("#site_report_main_url").append(text);

This takes a query parameter, massages it slightly (function getURI() merely removes the query/anchor part from a URL) and then inserts it into a localization string. The end result is added to the page by means of jQuery.append(), a function that will parse HTML code and insert the result into the DOM. At no point does this ensure that HTML code in the parameter won’t cause harm.

So a malicious website could open site_report.html?url=http://malware.wicar.org/

Exploiting XSS without running code

Any attempts to run JavaScript code through this vulnerability are doomed. That’s because the extension’s Content Security Policy looks like this:

"content_security_policy": "script-src 'self' 'unsafe-eval'; object-src 'self'",Why the developers relaxed the default policy by adding 'unsafe-eval' here? Beats me. But it doesn’t make attacker’s job any easier, without any eval() or new Function() calls in this extension. Not even jQuery will call eval() for inline scripts, as newer versions of this library will create actual inline scripts instead – something that browsers will disallow without an 'unsafe-inline' keyword in the policy.

So attackers have to use JavaScript functionality which is already part of the extension. The site report page has no interesting functionality, but the placeholder page does. This one has an “Accept the Risk” button which will add a blocked website to the extension’s whitelist. So my first proof of concept page used the following XSS payload:

<script type="module" src="chrome-extension://fheoggkfdfchfphceeifdbepaooicaho/block_page.js">

span>script>

<button id="block_page_accept_risk"

style="position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; bottom: 0; width: 100%;">

Dare to click!

span>button>This loads the extension’s block_page.js script so that it becomes active on the site report page. And it adds a button that this script will consider “Accept the Risk” button – only that the button’s text and appearance are freely determined by the attacker. Here, the button is made to cover all of page’s content, so that clicking anywhere will trigger it and produce a whitelist entry.

All the non-obvious quirks here are related to jQuery. Why type="module" on the script tag? Because jQuery will normally download script contents and turn them into an inline script which will then be blocked by the Content Security Policy. jQuery leaves ECMAScript modules alone however and these can execute normally.

Surprised that the script executes? That’s because jQuery doesn’t simply assign to innerHTML, it parses HTML code into a document fragment before inserting the results into the document.

Why don’t we have to generate any event to make block_page.js script attach its event listeners? That’s because the script relies on jQuery.ready() which will fire immediately if called in a document that already finished loading.

Getting out of the sandbox…

Now we’ve seen the general approach of exploiting existing extension functionality in order to execute actions without any own code. But are there actions that would produce more damage than merely adding whitelist entries? When looking through extension’s functionality, I noticed an unused options page – extension configuration would normally be done by an external application. That page and the corresponding script could add and remove whitelist entries for example. And I noticed that this page was vulnerable to XSS via malicious whitelist entries.

So there is another XSS vulnerability which wouldn’t let attackers execute any code, now what? But that options page is eerily similar to the one displayed by the external application. Could it be that the application is also displaying an HTML-based page? And maybe, just maybe, that page is also vulnerable to XSS? I mean, we could use the following payload to add a malicious whitelist entry if the user clicks somewhere on the page:

<script type="module" src="chrome-extension://fheoggkfdfchfphceeifdbepaooicaho/settings.js">

span>script>

<button id="add-btn"

style="position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; bottom: 0; width: 100%;">

Dare to click!

span>button>

<input id="settings_whitelist_input"

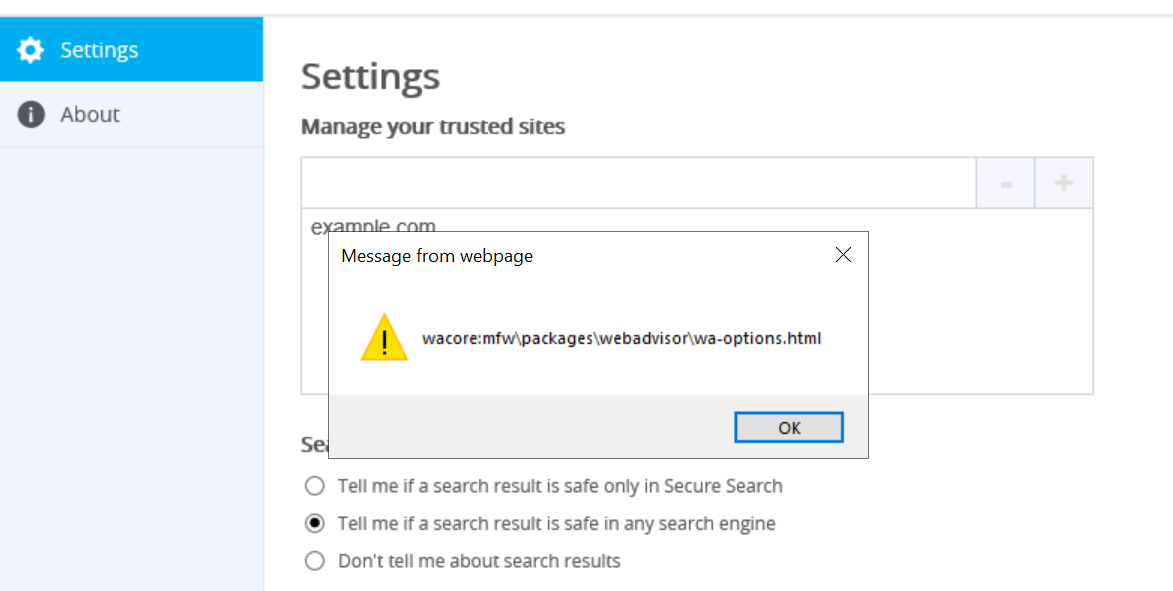

value="example.com">And if we then open WebAdvisor options…

This is no longer the browser extension, it’s the external UIHost.exe application. The application has an HTML-based user interface and it is also using jQuery to manipulate it, not bothering with XSS prevention of any kind. No Content Security Policy is stopping us here any more, anything goes.

Of course, attackers don’t have to rely on the user opening options themselves. They can rather instrument further extension functionality to open options programmatically. That’s what my proof of concept page did: first click would add a malicious whitelist entry, second click opened the options then.

… and into the system

It’s still regular JavaScript code that is executing in UIHost.exe, but it has access to various functions exposed via window.external. In particular, window.external.SetRegistryKey() is very powerful, it allows writing any registry keys. And despite UIHost.exe running with user privileges, this call succeeds on HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE keys as well – presumably asking the McAfee WebAdvisor service to do the work with administrator privileges.

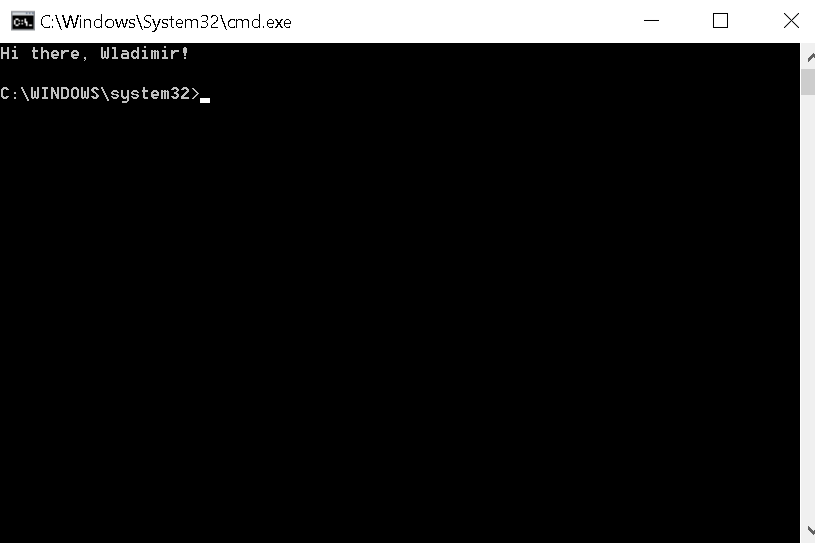

So now attackers only need to choose a registry key that allows them to run arbitrary code. My proof of concept used the following payload in the end:

window.external.SetRegistryKey('HKLM',

'SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run',

'command',

'c:\\windows\\system32\\cmd.exe /k "echo Hi there, %USERNAME%!"',

'STR',

'WOW64',

false),

window.external.Close()

This calls window.external.Close() so that the options window closes immediately and the user most likely won’t even see it. But it also adds a command to the registry that will be run on startup. So when any user logs on, they will get this window greeting them:

Yes, I cheated. I promised administrator privileges, yet this command executes with user’s privileges. In fact, with privileges of any user of the affected system who dares to log on. Maybe you’ll just believe me that attackers who can write arbitrary values to the registry can achieve admin privileges? No? Ok, there is this blog post which explains how writing to \SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Image File Execution Options\wsqmcons.exe and adding a “debugger” will get you there.

Conclusions

The remarkable finding here: under some conditions, not even a restrictive Content Security Policy value will prevent an XSS vulnerability from being exploited. And “some conditions” in this particular case means: using jQuery. jQuery doesn’t merely encourage a coding style that’s prone to introducing XSS vulnerabilities, here both in the browser extension and the standalone application. Its unusual handling of HTML code also means that

|

|

Mozilla Open Policy & Advocacy Blog: Goals for USA FREEDOM reauthorization: reforms, access, and transparency |

At Mozilla, we believe that privacy is a fundamental digital right. We’ve built these values into the Firefox browser itself, and we’ve pushed Congress to pass strong legal protections for consumer privacy in the US. This week, Congress will have another opportunity to consider meaningful reforms to protect user privacy when it debates the reauthorization of the USA FREEDOM Act. We believe that Congress should amend this surveillance law to remove ineffective programs, bolster resources for civil liberties advocates, and provide more transparency for the public. More specifically, Mozilla supports the following reforms:

- Elimination of the Call Detail Record program

- Greater access to information for amicus curiae

- Public access to all significant opinions from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court

By taking these steps, we believe that Congress can ensure the continued preservation of civil liberties while allowing for appropriate government access to information when necessary.

Eliminate the Call Detail Record Program

First, Congress should revoke the authority for the Call Detail Record (CDR) program. The CDR program allows the federal government to obtain the metadata of phone calls and texts from telecom companies in the course of an international terrorism investigation, subject to specific statutory requirements. This program is simply no longer worthwhile. Over the last four years, the National Security Agency (NSA) scaled back its use of the program, and the agency has not used this specific authority since late 2018.

The decision to suspend the program is a result of challenges the agency encountered in effectively operating the program on three separate fronts. First, the NSA has had issues with the mass overcollection of phone records that it was not authorized to receive, intruding into the private lives of millions of Americans. This overcollection represents a mass breach of civil liberties–a systemic violation of our privacy. Without technical measures to maintain these protections, the program was no longer legally sustainable.

Second, the program may not provide sufficiently valuable insights in the current threat environment. In a recent Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, the government acknowledged that the intelligence value of the program was outweighed by the costs and technical challenges associated with its continued operation. This conclusion was supported by an independent analysis from the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB), which hopes to publicly release an unclassified version of its report in the near future. Additionally, the shift to other forms of communications may make it even less likely that law enforcement will obtain useful information through this specific authority in the future.

And finally, some technological shifts may have made the CDR program too complex to implement today. Citing to “technical irregularities” in some of the data obtained from telecom providers under the program, the NSA deleted three years’ worth of CDRs that it was not authorized to receive last June. While the agency has not released a specific explanation, Susan Landau and Asaf Lubin of Tufts University have posited that the problem stems from challenges associated with measures in place to facilitate interoperability between landlines and mobile phone networks.

The NSA has recommended shutting down the program, and Congress should follow suit by allowing it to expire.

Bolster Access for Advocates

The past four years have illustrated the need to expand the resources of civil liberties advocates working within the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) itself. Under statute, these internal advocates are designated by the court as a part of the amicus curiae program to provide assistance and insight. Advocates on the panel have expertise in privacy, civil liberties, or other relevant legal or technical issues, and the law mandates access to all materials that the court determines to be relevant to the duties of the amicus curiae.

Unfortunately, the law does not guarantee that the panel will have access to the data held by the government, limiting the insight of the panel into the actual merits of the case and impairing its ability to protect civil liberties. To correct this inequity, Congress should amend the statute to ensure that the amicus curiae has access to any information held by the government that the amicus believes is relevant to the purposes of its appointment. By doing so, amici will be better equipped to fulfill its duties with a more complete picture of the underlying case.

More Transparency for the Public

Finally, the American public also deserves more information about how surveillance authorities are being used. The USA FREEDOM Act had provisions intended to spur greater public disclosure, particularly regarding decisions or orders issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) that contained significant interpretations of the Constitution or other laws. While the Court was originally designed in 1978 to address a relatively narrow universe of foreign surveillance cases, its mission has since expanded and it now routinely rules on fundamental issues of Constitutional law that may affect every citizen. Given the importance and scope of this growing body of jurisprudence, Congress should protect public access to the law and ensure that all cases with significant opinions are released.

Historically, the FISC has been reluctant to publicly release their decisions, despite the best efforts of civil society advocates. In recent litigation, the most prominent point of contention has been whether the FISC is obligated to release opinions issued before the enactment of the USA FREEDOM Act in May 2015. The legislative history and the text of the statute itself does not include any reference of such a limitation–senior members of the House Judiciary Committee explicitly stated that the provision was intended to require the government to “declassify and publish all novel significant opinions” of FISC during legislative debate. Congress should take this opportunity to re-emphasize their intent by amending the statute with explicit language to compel the release of all such decisions.

Ultimately, these reforms represent a necessary step forward to better protect the civil liberties of US users. By removing ineffective programs, expanding access to information for internal advocates, and providing greater transparency for the public, Congress can build upon critical privacy safeguards and support checks on the future use of surveillance authorities. Our hope is that Congress will adopt these reforms and give people the protections that they deserve.

The post Goals for USA FREEDOM reauthorization: reforms, access, and transparency appeared first on Open Policy & Advocacy.

|

|

Firefox UX: Critiquing Design |

This is me about 25 years ago, dancing with a yoga ball. I was part of a theater company where I first learned Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process. We used this extensively—it was an integral part of our company dynamic. We used it to develop company work, we used it in our education programs and we even used it to redesign our company structure. It was a formative part of my development as an artist, a teacher, and later, as a user-centered designer.

This is me about 25 years ago, dancing with a yoga ball. I was part of a theater company where I first learned Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process. We used this extensively—it was an integral part of our company dynamic. We used it to develop company work, we used it in our education programs and we even used it to redesign our company structure. It was a formative part of my development as an artist, a teacher, and later, as a user-centered designer.

What I love about this process is that works by embedding all the things we strive for in a critique into a deceptively simple, step-by-step process. You don’t have to try to remember everything the next time you’re knee-deep in a critique session. It’s knowledge in the world for critique sessions.

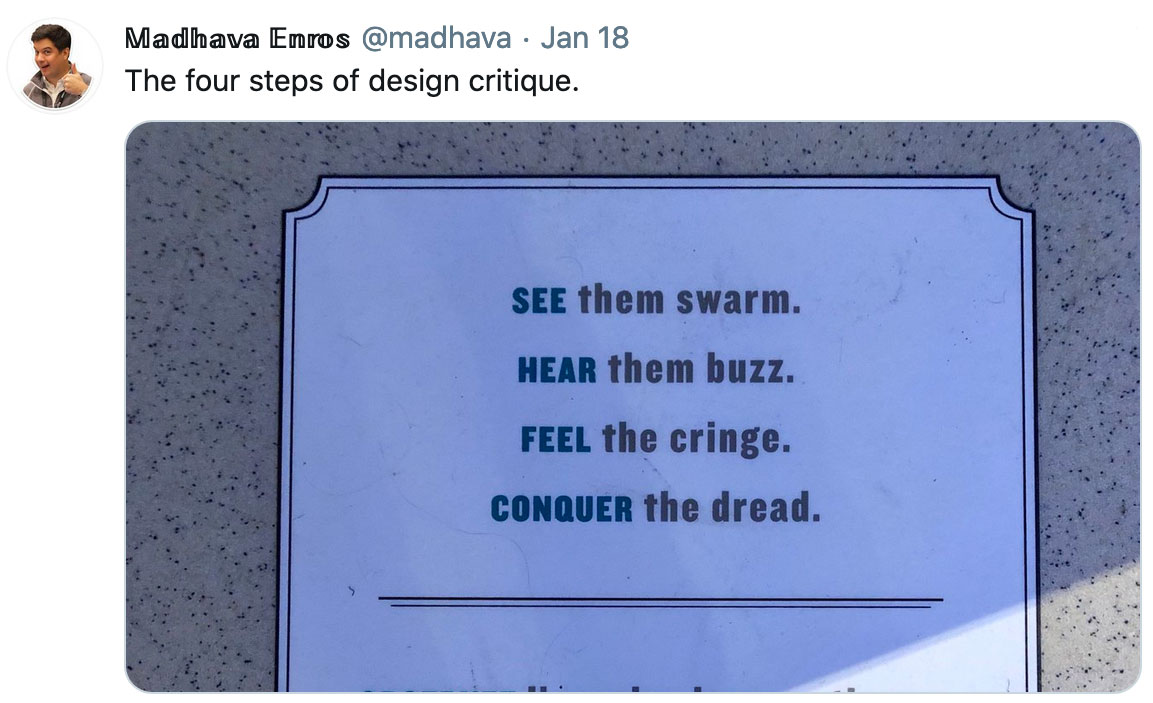

So a while back I started thinking about how I could adapt this to critiquing design and I introduced the process to the Firefox UX team. We’ve been practicing and refining it since last summer and we’ve really found it helpful. Recently I’ve been getting requests to share our adapted version with other design teams so I’ve collected my notes and the cheat sheet we use to keep us on track over at critiquing.design. Please feel free to try it out. Let me know if you have questions or ideas to make it better. I’ve also started a GitHub repo for it so you can file an issue or make pull request if you want.

The other great part about this is that it changes critique from something like:

To a time that I look forward to and that leaves me inspired by the smart, creative people I work with.

To a time that I look forward to and that leaves me inspired by the smart, creative people I work with.

|

|

Cameron Kaiser: TenFourFox FPR20b1 available |

TenFourFox Feature Parity Release 20 beta 1 is now available (downloads, hashes, release notes). Now here's an acid test: I watched the entire Democratic presidential debate live-streamed on the G5 with TenFourFox FPR20b1 and the MP4 Enabler, and my G5 did not burst into flames either from my code or their rhetoric. (*Note: Any politician of any party can set your G5 on fire. It's what they do.)

When using FPR20 you should notice ... absolutely nothing. Sites should just appear as they do; the only way you'd know anything changed in this version is if you pressed Command-I and looked at the Security tab to see that you're connected over TLS 1.3, the latest TLS security standard. In fact, the entirety of the debate was streamed over it, and to the best of my knowledge TenFourFox is the only browser that implements TLS 1.3 on Power Macs running Mac OS X. On regular Firefox your clue would be seeing occasional status messages about handshakes, but I've even disabled that for TenFourFox to avoid wholesale invalidating our langpacks which entirely lack those strings. Other than a couple trivial DOM updates I wrote up because they were easy, as before there are essentially no other changes other than the TLS enablement in this FPR to limit the regression range. If you find a site that does not work, verify first it does work in FPR19 or FPR18, because sites change more than we do, and see if setting security.tls.version.max to 3 (instead of 4) fixes it. You may need to restart the browser to make sure. If this does seem to reliably fix the problem, report it in the comments. A good test site is Google or Mozilla itself. The code we are using is largely the same as current Firefox's.

I have also chosen to enable Zero Round Trip Time (0-RTT) to get further speed. The idea with 0RTT is that the browser, having connected to a particular server before and knowing all the details, will not wait for a handshake and immediately starts sending encrypted data using a previous key modified in a predictable fashion. This saves a handshake and is faster to establish the connection. If many connections or requests are made, the potential savings could be considerable, such as to a site like Google where many connections may be made in a short period of time. 0RTT only happens if both the client and server allow it and there are a couple technical limitations in our implementation that restrict it further (I'm planning to address these assuming the base implementation sticks).

0RTT comes with a couple caveats which earlier made it controversial, and some browsers have chosen to unconditionally disable it in response. A minor one is a theoretical risk to forward secrecy, which would require a malicious server caching keys (but a malicious server could do other more useful things to compromise you) or an attack on TenFourFox to leak those keys. Currently neither is a realistic threat at present, but the potential exists. A slightly less minor concern is that users requiring anonymity may be identified by 0RTT pre-shared keys being reused, even if they change VPNs or exit nodes. However, the biggest is that, if handled improperly, it may facilitate a replay attack where encrypted data could be replayed to trigger a particular action on the server (such as sending Mallory a billion dollars twice). Firefox/TenFourFox avoid this problem by never using 0RTT when a non-idempotent action is taken (i.e., any HTTP method that semantically changes state on the server, as opposed to something that merely fetches data), even if the server allows it. Furthermore, if the server doesn't allow it, then 0RTT is not used (and if the server inappropriately allows it, consider that their lack of security awareness means they're probably leaking your data in other, more concerning ways too).

All that said, even considering these deficiencies, TLS 1.3 with 0-RTT is still more secure than TLS 1.2, and the performance benefits are advantageous. Thus, the default in current Firefox is to enable it, and I think this is the right call for TenFourFox as well. If you disagree, set security.tls.enable_0rtt_data to false.

FPR20 goes live on or about March 10.

http://tenfourfox.blogspot.com/2020/02/tenfourfox-fpr20b1-available.html

|

|

L. David Baron: Semantic markup, browsers, and identity in the DOM |

HTML was initially designed as a semantic markup language,

with elements having semantics (meaning)

describing general roles within a document.

These semantic elements have been added to over time.

Markup as it is used on the web is often criticized for not following the semantics,

but rather being a soup of divs and spans,

the most generic sorts of elements.

The Web has also evolved over the last 25 years from a web of documents

to a web where many of the most visited pages are really applications rather than documents.

The HTML markup used on the Web is a representation of a tree structure,

and the user interface of these web applications

is often based on dynamic changes made through the DOM,

which is what we call both the live representation of that tree structure

and the API through which that representation is accessed.

Browsers exist as tools for users to browse the Web; they strike a balance between showing the content as its author intended versus adapting that content to the device it is being displayed on and the preferences or needs of the user.

Given the unreliable use of semantics on the Web, most of the ways browsers adapt content to the user rarely depend deeply on semantics, although some of them (such as reader mode) do have significant dependencies. However, browser adaptations of content or interventions that browsers make on behalf of the user very frequently depend on the persistent object identity in the DOM. That is, nodes in the DOM tree (such as sections of the page, or paragraphs) have an identity over the lifetime of the page, and many things that browsers do depend on that identity being consistent over time. For example, exposing the page to a screen reader, scroll anchoring, and I think some aspects of ad blocking all depend on the idea that there are elements in the web page that the browser understands the identity of over time.

This might seem like it's not a very interesting observation. However, I believe it's important in the context of frameworks, like React, that use a programming model (which many developers find easier) where the developer writes code to map application state to user interface rather than having to worry about constantly altering the DOM to match the current state. These frameworks have an expensive step where they have to map the generated virtual DOM into a minimal set of changes to the real DOM. It is well known that it's important for performance for this set of changes to be minimal, since making fewer changes to the DOM results in the browser doing less work to render the updated page. However, this process is also important for the site to be a true part of the Web, since this rectification is important for being something that the browser can properly adapt to the device and to the user's needs.

|

|

Chris H-C: This Week in Glean: A Distributed Team Echoes Distributed Workflow |

(“This Week in Glean” is a series of blog posts that the Glean Team at Mozilla is using to try to communicate better about our work. They could be release notes, documentation, hopes, dreams, or whatever: so long as it is inspired by Glean. You can find an index of all TWiG posts online.)

Last Week: Extending Glean: build re-usable types for new use-cases by Alessio

I was recently struck by a realization that the position of our data org’s team members around the globe mimics the path that data flows through the Glean Ecosystem.

Glean Data takes this five-fold path (corresponding to five teams):

- Data is collected in a client using the Glean SDK (Glean Team)

- Data is transmitted to the Structured Ingestion pipeline (Data Platform)

- Data is stored and maintained in our infrastructure (Data Operations)

- Data is presented in our tools (Data Tools)

- Data is analyzed and reported on (Data Science)

The geographical midpoint of the Glean Team is about halfway across the north atlantic. For Data Platform it’s on the continental US, anchored by three members in the midwestern US. Data Ops is further West still, with four members in the Pacific timezone and no Europeans. Data Tools breaks the trend by being a bit further East, with fewer westcoasters. Data Science (for Firefox) is centred farther west still, with only two members East of the Rocky Mountains.

Or, graphically:

Given the rotation of the Earth, the sun rises first on the Glean Team and the data collected by the Glean SDK. Then the data and the sun move West to the Data Platform where it is ingested. Data Tools gets the data from the Platform as morning breaks over Detroit. Data Operations keeps it all running from the midwest. And finally, the West Coast Centre of Firefox Data Science Excellence greets the data from a mountaintop, to try and make sense of it all.

(( Lying orthogonal to the data organization is the secret Sixth Glean Data “Team”: Data Stewardship. They ensure all Glean Data is collected in accordance with Mozilla’s Privacy Promise. The sun never sets on the Stewardship’s global coverage, and it’s a volunteer effort supplied from eight teams (and growing!), so I’ve omitted them from this narrative. ))

Bad metaphors about sunlight aside, I wonder whether this is random or whether this is some sort of emergent behaviour.

Conway’s Law suggests that our system architecture will tend to reflect our orgchart (well, the law is a bit more explicit about “communication structure” independent of organizational structure, but in the data org’s case they’re pretty close). Maybe this is a specific example of that: data architecture as a reflection of orgchart geography.

Or perhaps five dots on a globe that are only mostly in some order is too weak of a coincidence to even bear thinking about? Nah, where’s the blog post in that thinking…

If it’s emergent, it then becomes interesting to consider the “chicken and egg” point of view: did the organization beget the system or the system beget the organization? When I joined Mozilla some of these teams didn’t exist. Some of them only kinda existed within other parts of the company. So is the situation we’re in today a formalization by us of a structure that mirrors the system we’re building, or did we build the system in this way because of the structure we already had?

:chutten

|

|

Mike Hoye: Synchronous Messaging: We’re Live. |

After a nine month leadup, chat.mozilla.org, our Matrix-based replacement for IRC, has been up running for about a month now.

While we’ve made a number of internal and community-facing announcements about progress, access and so forth, we’ve deliberately run this as a quiet, cautious, low-key rollout, letting our communities find their way to chat.m.o and Matrix organically while we sort out the bugs and rough edges of this new experience.

Last week we turned on federation, the last major step towards opening Mozilla to the wider Matrix ecosystem, and it’s gone really well. Which means that as of last week, Mozilla’s transition from IRC to Matrix is within arm’s reach of done.

The Matrix team have been fantastic partners throughout this process, open to feedback and responsive to concerns throughout. It’s been a great working relationship, and as investments of effort go one that’s already paying off exactly the way want our efforts to pay off, with functional, polish and accessibility improvements that benefit the entire Matrix ecosystem coming from the feedback from the Mozilla community.

We still have work to do, but this far into the transition it sure feels like winning. The number of participants in our primary development channels has already exceeded their counterparts on IRC at their most active, and there’s no sign that’s slowing down. Many of our engineering and ops teams are idling or archiving their Slack channels and have moved entirely to Matrix, and that trend isn’t slowing down either.

As previously announced, we’re on schedule to turn off IRC.m.o at the end of the month, and don’t see a reason to reconsider that decision. So far, it looks like we’re pretty happy on the new system. It’s working well for us.

So: Welcome. If you’re new to Mozilla or would like to get involved, come see us in the #Introduction channel on our shiny new Matrix system. I hope to see you there.

http://exple.tive.org/blarg/2020/02/20/synchronous-messaging-were-live/

|

|

Daniel Stenberg: The command line options we deserve |

A short while ago curl‘s 230th command line option was added (it was --mail-rcpt-allowfails). Two hundred and thirty command line options!

A look at curl history shows that on average we’ve added more than ten new command line options per year for very long time. As we don’t see any particular slowdown, I think we can expect the number of options to eventually hit and surpass 300.

Is this manageable? Can we do something about it? Let’s take a look.

Why so many options?

There are four primary explanations why there are so many:

- curl supports 24 different transfer protocols, many of them have protocol specific options for tweaking their operations.

- curl’s general design is to allow users to individual toggle and set every capability and feature individually. Every little knob can be on or off, independently of the other knobs.

- curl is feature-packed. Users can customize and adapt curl’s behavior to a very large extent to truly get it to do exactly the transfer they want for an extremely wide variety of use cases and setups.

- As we work hard at never breaking old scripts and use cases, we don’t remove old options but we can add new ones.

An entire world already knows our options

curl is used and known by a large amount of humans. These humans have learned the way of the curl command line options, for better and for worse. Some thinks they are strange and hard to use, others see the logic behind them and the rest simply accepts that this is the way they work. Changing options would be conceived as hostile towards all these users.

curl is used by a very large amount of existing scripts and programs that have been written and deployed and sit there and do their work day in and day out. Changing options, even ever so slightly, risk breaking some to many of these scripts and make a lot of developers out there upset and give them everything from nuisance to a hard time.

curl is the documented way to use APIs, REST calls and web services in numerous places. Lots of examples and tutorials spell out how to use curl to work with services all over the world for all sorts of interesting things. Examples and tutorials written ages ago that showcase curl still work because curl doesn’t break behavior.

curl command lines are even to some extent now used as a translation language between applications:

All the four major web browsers let you export HTTP requests to curl command lines that you can then execute from your shell prompts or scripts. Other web tools and proxies can also do this.

There are now also tools that can import said curl command lines so that they can figure out what kind of transfer that was exported from those other tools. The applications that import these command lines then don’t want to actually run curl, they want to figure out details about the request that the curl command line would have executed (and instead possibly run it themselves). The curl command line has become a web request interchange language!

There are also a lot of web services provided that can convert a curl command line into a source code snippet in a variety of languages for doing the same request (using the language’s native preferred method). A few examples of this are: curl as DSL, curl to Python Requests, curl to Go, curl to PHP and curl to perl.

Can the options be enhanced?

I hope I’ve made it clear why we need to maintain the options we already support. However, it doesn’t limit what we can add or that we can’t add new ways of doing things. It’s just code, of course it can be improved.

We could add alternative options for existing ones that make sense, if there are particular ones that are considered complicated or messy.

We could add a new “mode” that would have a totally new set of options or new way of approaching what we think of options today.

Heck, we could even consider doing a separate tool next to curl that would similarly use libcurl for the transfers but offer a totally new command line option approach.

None of these options are ruled out as too crazy or far out. But they all of course require that someone think of them as a good ideas and is prepared to work on making it happen.

Are the options hard to use?

Oh what a subjective call.

Packing this many features into a single tool and having every single option and superpower intuitive and easy-to-use is perhaps not impossible but at least a very very hard task. Also, the curl command line options have been added organically over a period of over twenty years so some of them of could of course have been made a little smarter if we could’ve foreseen what would come or how the protocols would later change or improve.

I don’t think curl is hard to use (what you think I’m biased?).

Typical curl use cases often only need a very small set of options. Most users never learn or ever need to learn most curl options – but they are there to help out when the day comes and the user wants that particular extra quirk in their transfer.

Using any other tool, even those who pound their chest and call themselves user-friendly, if they grow features close to the amount of abilities that curl can do, such command lines also grow substantially and will no longer always be intuitive and self-explanatory. I don’t think a very advanced tool can remain easy to use in all circumstances. I think the aim should be to keep the commonly use cases easy. I think we’ve managed this in curl, in spite of having 230 different command line options.

Should we have another (G)UI?

Would a text-based or even graphical UI help or improve curl? Would you use one if it existed? What would it do and how would it work? Feel most welcome to tell me!

Related

See the cheat sheet refreshed and why not the command line option of the week series.

https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2020/02/20/the-command-line-options-we-deserve/

|

|

Mozilla Localization (L10N): L10n Report: February Edition |

Welcome!

Please note some of the information provided in this report may be subject to change as we are sometimes sharing information about projects that are still in early stages and are not final yet.

New localizers

- Bora of Kabardian joined us through the Common Voice project

- Kevin of Swahili

- Habib and Shamim of Bengali joined us through the WebThings Gateway project

Are you a locale leader and want us to include new members in our upcoming reports? Contact us!

New community/locales added

- Karakalpak

- Luganda: revitalization of the community, thanks to the Common Voice projects.

- Scots

New content and projects

What’s new or coming up in Firefox desktop

Firefox is now officially following a 4-weeks release cycle:

- Firefox 74 is currently in beta and it will be released on March 10. The deadline to update your localization is February 25.

- Firefox 75, currently in Nightly, will move to Beta when 74 is officially released. The deadline to update localizations for that version will be on March 24 (4 weeks after the current deadline).

In terms of localization priority and deadlines, note that the content of the What’s new panel, available at the bottom of the hamburger menu, doesn’t follow the release train. For example, content for 74 has been exposed on February 17, and it will be possible to update translations until the very end of the cycle (approximately March 9), beyond the normal deadline for that version.

What’s new or coming up in mobile

We have some exciting news to announce on the Android front!

Fenix, the new Android browser, is going to release in April. The transition from Firefox for Android (Fennec) to Fenix has already begun! Now that we have an in-app locale switcher in place, we have the ability to add languages even when they are not supported by the Android system itself.

As a result, we’ve opened up the project on Pontoon to many new locales (89 total). Our goal is to reach Firefox for Android parity in terms of completion and number of locales.