Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://www.roughtype.com/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://feeds.feedburner.com/roughtype/ungc, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Rough Type has a new RSS feed |

As a result of attacks by hackers intent on selling bootleg viagra and other goodies, Rough Type has made a hasty switch to a new blogging platform (WordPress). As a result, the old RSS feed has been replaced by a new one. If you'd like to continue to subscribe to Rough Type, here's the new subscription link:

http://www.roughtype.com/?feed=rss2

You can also re-subscribe through the home page.

I apologize for the duplicate links in recent days and appreciate your interest in my work.

Nick

http://www.roughtype.com/archives/2012/06/rough_type_has_a_new_rss_feed.php

|

|

Понравилось: 14 пользователям

Rough Type is experiencing technical difficulties |

I guess this is what I get for delaying a software upgrade for seven years. Things should be back to normal reasonably soon.

http://www.roughtype.com/archives/2012/06/rough_type_is_experiencing_tec.php

|

|

Rough Type is experiencing technical difficulties |

I guess this is what I get for delaying a software upgrade for seven years. Things should be back to normal reasonably soon.

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/06/rough_type_is_experiencing_tec.html

|

|

Rough Type is experiencing technical difficulties |

http://www.roughtype.com/archives/2012/06/rough-type-is-e.php

|

|

What realtime is before it's realtime |

They say that there's a brief interlude, measured in milliseconds, between the moment a thought arises in the cellular goop of our brain and the moment our conscious mind becomes aware of that thought. That gap, they say, swallows up our free will and all its attendant niceties. After the fact, we pretend that something we think of as "our self" came up with something we think of as "our thought," but that's all just make-believe. In reality, they say, we're mere automatons, run by some inscrutable Oz hiding behind a synaptical curtain.

The same thing goes for sensory perception. What you see, touch, hear, smell are all just messages from the past. It takes time for the signals to travel from your sensory organs to your sense-making brain. Milliseconds. You live, literally, in the past.

Now is then. Always.

As the self-appointed chronicler of realtime, as realtime's most dedicated cyber-scribe, I find this all unendurably depressing. The closer our latency-free networks and devices bring us to realtime, the further realtime recedes. The net trains us to think not in years or seasons or months or weeks or days or hours or even minutes. It trains us to think in seconds and fractions of seconds. Google says that if it takes longer than the blink of an eye for a web page to load, we're likely to bolt for greener pastures. Microsoft says that if a site lags 250 milliseconds behind competing sites, it can kiss its traffic goodbye. The SEOers know the score (even if they don't know the tense):

Back in 1999 the acceptable load time for a site is 8 seconds. It decreased to 4 seconds in 2004, and 2 seconds in 2009. These are based on the study of the behavior of the online shoppers. Our expectations already exceed the 2-second rule, and we want it faster. This 2012, we’re going sub-second.

And yet, as we become more conscious of each passing millisecond, it becomes harder and harder to ignore the fact that we're always a moment behind the real, that what we imagine to be realtime is really just pseudorealtime. A fraud.

They say a man never steps into the same stream twice. But that same man will never step into a web stream even once. It's long gone by the time he becomes conscious of his virtual toe hitting the virtual flow. That tweet/text/update/alert you read so hungrily? It may as well be an afternoon newspaper tossed onto your front stoop by some child-laborer astride a banana bike. It's yesterday.

But there's hope. The net, Andrew Keen reports on the eve of Europe's Le Web shindig, is about to get, as the conference's official theme puts it, "faster than realtime." What does that mean? The dean of social omnipresence, Robert Scoble, explains: "It's when the server brings you a beer before you ask for it because she already knows what you drink!" Le Web founder Loic Le Meur says to Keen, "We've arrived in the future":

Online apps are getting to know us so intimately, he explained, that we can know things before they happen. To illustrate his point, Le Meur told me about his use of Highlight, a social location app which offers illuminating data about nearby people who have signed up for the network like - you guessed it - the digitally omniscient Robert Scoble. Highlight enabled Le Meur to literally know the future before it happened because, he says, it is measuring our location all of the time. "I opened the door before he was there because I knew he was coming," Le Meur told me excitedly about a recent meeting that he had in the real world with Scoble.

I opened the door before he was there because I knew he was coming. I could repeat that sentence to myself endlessly - it's that beautiful. And it's profound. Our apps will anticipate our synapses. Our apps will deliver our pre-conscious thoughts to our consciousness before they've even become pre-conscious thoughts. The net will out-Oz Oz. Life will become redundant, but that seems a small price to pay for a continuous preview of real realtime.

Le Meur states the obvious to Keen:

We have "no choice but to fully embrace" today's online products, Le Meur told me about technology which he describes as "unheralded" in history.

We've never had any choice. Choice is an illusion. But now, as our gadgets tap into pre-realtime on our behalf, we'll at least know of the choice we never really made before we've even had the chance to not really make it. Yes, indeed. We've arrived in the future, and the future isn't even there yet. But, like Scoble, it's about to show up.

Now where the hell's that beer?

This post is an installment in Rough Type's ongoing series "The Realtime Chronicles," which began here.

http://www.roughtype.com/archives/2012/06/what_realtime_is_before_its_re.php

|

|

What realtime is before it's realtime |

They say that there's a brief interlude, measured in milliseconds, between the moment a thought arises in the cellular goop of our brain and the moment our conscious mind becomes aware of that thought. That gap, they say, swallows up our free will and all its attendant niceties. After the fact, we pretend that something we think of as "our self" came up with something we think of as "our thought," but that's all just make-believe. In reality, they say, we're mere automatons, run by some inscrutable Oz hiding behind a synaptical curtain.

The same thing goes for sensory perception. What you see, touch, hear, smell are all just messages from the past. It takes time for the signals to travel from your sensory organs to your sense-making brain. Milliseconds. You live, literally, in the past.

Now is then. Always.

As the self-appointed chronicler of realtime, as realtime's most dedicated cyber-scribe, I find this all unendurably depressing. The closer our latency-free networks and devices bring us to realtime, the further realtime recedes. The net trains us to think not in years or seasons or months or weeks or days or hours or even minutes. It trains us to think in seconds and fractions of seconds. Google says that if it takes longer than the blink of an eye for a web page to load, we're likely to bolt for greener pastures. Microsoft says that if a site lags 250 milliseconds behind competing sites, it can kiss its traffic goodbye. The SEOers know the score (even if they don't know the tense):

Back in 1999 the acceptable load time for a site is 8 seconds. It decreased to 4 seconds in 2004, and 2 seconds in 2009. These are based on the study of the behavior of the online shoppers. Our expectations already exceed the 2-second rule, and we want it faster. This 2012, we’re going sub-second.

And yet, as we become more conscious of each passing millisecond, it becomes harder and harder to ignore the fact that we're always a moment behind the real, that what we imagine to be realtime is really just pseudorealtime. A fraud.

They say a man never steps into the same stream twice. But that same man will never step into a web stream even once. It's long gone by the time he becomes conscious of his virtual toe hitting the virtual flow. That tweet/text/update/alert you read so hungrily? It may as well be an afternoon newspaper tossed onto your front stoop by some child-laborer astride a banana bike. It's yesterday.

But there's hope. The net, Andrew Keen reports on the eve of Europe's Le Web shindig, is about to get, as the conference's official theme puts it, "faster than realtime." What does that mean? The dean of social omnipresence, Robert Scoble, explains: "It's when the server brings you a beer before you ask for it because she already knows what you drink!" Le Web founder Loic Le Meur says to Keen, "We've arrived in the future":

Online apps are getting to know us so intimately, he explained, that we can know things before they happen. To illustrate his point, Le Meur told me about his use of Highlight, a social location app which offers illuminating data about nearby people who have signed up for the network like - you guessed it - the digitally omniscient Robert Scoble. Highlight enabled Le Meur to literally know the future before it happened because, he says, it is measuring our location all of the time. "I opened the door before he was there because I knew he was coming," Le Meur told me excitedly about a recent meeting that he had in the real world with Scoble.

I opened the door before he was there because I knew he was coming. I could repeat that sentence to myself endlessly - it's that beautiful. And it's profound. Our apps will anticipate our synapses. Our apps will deliver our pre-conscious thoughts to our consciousness before they've even become pre-conscious thoughts. The net will out-Oz Oz. Life will become redundant, but that seems a small price to pay for a continuous preview of real realtime.

Le Meur states the obvious to Keen:

We have "no choice but to fully embrace" today's online products, Le Meur told me about technology which he describes as "unheralded" in history.

We've never had any choice. Choice is an illusion. But now, as our gadgets tap into pre-realtime on our behalf, we'll at least know of the choice we never really made before we've even had the chance to not really make it. Yes, indeed. We've arrived in the future, and the future isn't even there yet. But, like Scoble, it's about to show up.

Now where the hell's that beer?

This post is an installment in Rough Type's ongoing series "The Realtime Chronicles," which began here.

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/06/what_realtime_is_before_its_re.html

|

|

What realtime is before it's realtime |

|

|

What realtime is before it's realtime |

|

|

1964 |

From Simon Reynolds's interview with Greil Marcus in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

SR: I wanted to ask you about an experience that seems to have been utterly formative and enduringly inspirational: the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in 1964. That is a real touchstone moment for you, right?

GM: That was a cauldron. It was a tremendously complex experience, struggle, event. A series of events. In a lot of ways, it's been misconstrued: there are many versions of it. Each person had their own version of it. The affair began when there'd been a lot of protests in the Bay Area in the spring of 1964 against racist hiring practices. At the Bank of America, at car dealerships, at the Oakland Tribune —black people were not hired at all for any visible job. So there were no black sales people, no black tellers or clerks. A lot of the organizing for these protests, which involved mass arrests and huge picket lines and publicity, was done on the Berkeley campus. Different political groups would set up a table and distribute leaflets and collect donations and announce picket lines and sit-ins. The business community put a lot of pressure on the University of California to stop this, and the university instituted a policy that no political advocacy could take place on the campus. No distribution of literature, no information about events where the law might be broken. So people set up their tables anyway. And the university had them arrested. And out of that came the Free Speech Movement, saying, "We demand the right to speak freely on campus like anywhere else. We've read the Constitution." ...

This Free Speech Movement was an extraordinary series of events where people stepped out of the anonymity of their own lives and either spoke in public or argued with everybody they knew all the time. It was three or four solid months of arguing in public: in dorm rooms, on walks, on picket lines. "What's this place for? Why are we here? What's this country about? Is this country a lie, or can we keep its promises even if it won't?" All these questions had come to life, and it was just the most dynamic and marvelous experience. And there were moments of tremendous drama and fear and courage. I used to walk around the campus thinking how lucky I was to be here at that moment. You really had a sense not that history was being made in some real sense for the world, but that you were making your own history — you along with other people. You were taking part in events, you were shaping events. You weren't just witnessing events that would change your life. That, as I understood it, would leave you unsatisfied, because you couldn't reenact what Thomas Jefferson called the "public happiness" of acting in public with other people. He was referring to his own moments as a revolutionary, drafting the Declaration of Independence. In that meeting, people pledged their lives and their sacred honor. And they knew that if they lost, they'd all be shot. Because they were acting together in public, they were taken out of themselves. They were acting on a stage that they themselves had built. I wasn't the only one who felt that way. In that moment I didn't have to wonder how it would feel to be that free. I was that free. And so were countless other people.

SR: And while all this was going on, you also had the tremendous excitement of the Beatles, the Stones, and then, a little later, Bob Dylan. Must have been a pretty exciting time to be young.

GM: The Free Speech thing was the fall of 1964. And the Beatles dominated the spring of '64. One thing I will never forget about being a student here was reading in the San Francisco Chronicle that this British rock 'n' roll group was going to be on The Ed Sullivan Show. And I thought that sounded funny: I didn't know they had rock 'n' roll in England. So I went down to the commons room of my dorm to watch it and I figured there'd be an argument over what to watch. But instead there were 200 people there, and everybody had turned up to see The Ed Sullivan Show. "Where did all these people come from?" I didn't know people cared about rock 'n' roll. I thought it was quite odd. ...

I go back to my dorm room and all you're hearing is the Beatles, either on record or coming out of the radio. I sit down with this guy who's older than me — he's a senior, I'm a sophomore — and he was this very pompous kind of guy, but I'll never forget his words. It was late at night and he said, "Could be that just as our generation was brought together by Elvis Presley, it may be that we will be brought together again by the Beatles." What a bizarre thing to say! But of course he was right. Later that week I went down to Palo Alto — I had grown up there and in Menlo Park, on the Peninsula — and there was this one outpost of bohemianism, a coffee house called Saint Michael's Alley, where they only played folk music. But that night they were only playing Meet the Beatles. And it just sounded like the spookiest stuff I'd ever heard. Particularly "Don't Bother Me," the George Harrison song. So the spring of '64 was all Beatles. But the fall was something else.

|

|

1964 |

|

|

Live fast, die young and leave a beautiful hologram |

"For us, of course, it's about keeping Jimi authentically correct." So says Janie Hendrix, explaining the motivation behind her effort to turn her long-dead brother into a Strat-wielding hologram. Tupac Shakur's recent leap from grave to stage was just the first act of what promises to be an orgy of cultural necrophilia. Billboard reports that holographic second comings are in the works not just for Jimi Hendrix but for Elvis Presley, Jim Morrison, Otis Redding, Janis Joplin, Peter Tosh, and even Rick James. Superfreaky! What could be more authentically correct than an image of an image?

I'm really looking forward to seeing the Doors with Jim Morrison back out in front - that guy from the Cult never did it for me - but I admit it may be kind of discomforting to see the rest of the band looking semi-elderly while the Lizard King appears as his perfect, leather-clad 24-year-old self. Jeff Jampol, the Doors' manager, says, "Hopefully, 'Jim Morrison' will be able to walk right up to you, look you in the eye, sing right at you and then turn around and walk away." That's all well and good, but I'm sure Jampol knows that the crowd isn't going to be satisfied unless "Jim" whips out his virtual willy. (Can you arrest a hologram for obscenity?) In any case, hearing the Morrison Hologram sing "Cancel my subscription to the resurrection" is going to be just priceless - a once-in-a-lifetime moment, replayable endlessly.

I think it was Nietzsche who said that what kills you only makes you stronger in the marketplace.

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/06/live_fast_die_young_and_leave.html

|

|

Books ain't music |

C30, C60, C90, go!

Off the radio, I get a constant flow

Cause I hit it, pause it, record it and play

Or turn it rewind and rub it away!

-Bow Wow Wow, 1980

When I turned twelve, in the early 1970s, I received, as a birthday present from my parents, a portable, Realistic-brand cassette tape recorder from Radio Shack. Within hours, I became a music pirate. I had a friend who lived next door, and his older brother had a copy of Abbey Road, an album I had taken a shine to. I carried my recorder over to their house, set its little plastic microphone (it was a mono machine) in front of one of the speakers of their stereo, and proceeded to make a cassette copy of the record. I used the same technique at my own house to record hit songs off the radio as well as make copies of my siblings' and friends' LPs and 45s. It never crossed my mind that I was doing anything wrong. I didn't think of myself as a pirate, and I didn't think of my recordings as being illicit. I was just being a fan.

I was hardly unique. Tape recorders, whether reel-to-reel or cassette, were everywhere, and pretty much any kid who had access to one made copies of albums and songs. (If you've read Walter Isaacson's biography of Steve Jobs, you know that when Jobs went off to college in 1972, he brought with him a comprehensive collection of Dylan bootlegs on tape.) When, a couple of years later, cassette decks became commonplace components of stereo systems, ripping songs from records and the radio became even simpler. There was a reason that cassette decks had input jacks as well as output jacks. My friends and I routinely exchanged cassette copies of albums and mixtapes. It was the norm.

We also, I should point out, bought a lot of records, particularly when we realized that pretty much everything being played on the radio was garbage. (I apologize to all Doobie Brothers fans who happen to be reading this.) There are a few reasons why record sales and record copying flourished simultaneously. First, in order to make a copy of an album, someone in your circle of friends had to own an original; there were no anonymous, long-distance exchanges of music. Second, vinyl was a superior medium to tape because, among other things, it made it easier to play individual tracks (and it was not unusual to play a favorite track over and over again). Third, record sleeves were cool and they had considerable value in and of themselves. Fourth, owning the record had social cachet. And fifth, records weren't that expensive. What a lot of people forget about LPs back then is that most of them, not long after their original release, were remaindered as what were called cutouts, and you could pick them up for $1.99 or so. Even as a high-schooler working a part-time, minimum-wage job, you could afford to buy a couple of records a week, which was - believe it or not - plenty.

The reason I'm telling you all this is not that I suddenly feel guilty about my life as a teenage music pirate. I feel no guilt whatsoever. It's just that this weekend I happened to read an article in the Wall Street Journal, by Listen.com founder Rob Reid, which argued that "in the swashbuckling arena of digital piracy, the publishing world is acquitting itself far better than the brash music industry." Drawing a parallel between the music and book businesses, Reid writes:

The book business is now further into its own digital history than music was when Napster died. Both histories began when digital media became portable. For music, that was 1999, when the record labels ended a failing legal campaign to ban MP3 players. For books, it came with the 2007 launch of the Kindle. Publishing has gotten off to a much better start. Both industries saw a roughly 20% drop in physical sales four years after their respective digital kickoffs. But e-book sales have largely made up the shortfall in publishing—unlike digital music sales, which stayed stubbornly close to zero for years.

This doesn't prove that music lovers are crooks. Rather, it shows that actually selling things to early adopters is wise. Publishers did this—unlike the record labels, which essentially insisted that the first digital generation either steal online music or do without it entirely.

That all seems sensible enough. But Reid's argument is misleading. He oversimplifies media history, and he glosses over some big and fundamental differences between the book market and the music market. As my own youthful experience suggests, music lovers ARE crooks, and we've been crooks for decades. ("Crooks" is his term, of course, not mine.) Moreover, the "digital history" of music did not begin in 1999. It began in 1982 when albums began to be released on compact disk. Yes, there are some similarities between the music and book industries, and they're worth attending to, but the fact that the two industries have (so far) taken different courses in the digital era probably has far more to do with the basic differences between them - differences in history, technology, and customers, among other things - than with differences in executive decision-making.

Let me review some of the most salient differences and the way they've influenced the divergent paths the industries have taken:

Kids copied music long before music went digital. The unauthorized copying of songs and albums did not begin with the arrival of the web or of MP3s or of Napster. It has been a part of the culture of pop music since the 1960s. There has been no such tradition with books. Xeroxing a book was not an easy task, and it was fairly expensive, too. Nobody did it, except, maybe, for the occasional oddball. So, even though the large-scale trading of bootlegged songs made possible by the net had radically different implications for the music business than the small-scale trading that had taken place previously, digital copying and trading didn't feel particularly different from making and exchanging tapes. It seemed like a new variation on an old practice.

Fidelity matters less for popular music than for books. This seems counterintuitive, but it's true. I was happy with my copy of Abbey Road despite its abysmal sound quality and the fact that - horrors! - I had only recorded one channel of a stereo mix. Throughout the 1960s and well into the 70s, the main way a lot of people listened to music was through crappy a.m. car radios and crappy a.m. transistor radios. And need I mention eight-tracks? The human ear and the human brain seem to be very adept at turning lo-fi music signals into fulfilling listening experiences - the auditory imagination somehow fills in the missing signal. Early MP3s, though they were often ripped at very low bit rates, sounded just fine to the vast majority of the music-listening public, so quality was no barrier to mass piracy. A lo-fi copy of a book, in contrast, is a misery to read. Blurry text, missing pages, clunky navigation: it takes a very dedicated reader to overcome even fairly minor shortcomings in a copy of a book. That's one of the main reasons that even though bootlegged copies of popular books have been freely available online for quite some time now, few people bother with them.

Books never had a CD phase. Music was digitized long before the arrival of the web. During the 1980s, record companies digitized their catalogues, and digital CDs soon displaced tapes and vinyl as the medium of choice for music. The transition was a boon to the music industry because a whole lot of consumers bought new CD copies of albums that they already owned on vinyl. But the boon (as Reid notes) also set the stage for the subsequent bust. When personal computers with CD-ROM drives made it possible to rip music CDs into MP3 files, all the music that most people would ever want was soon available in a form that could be easily exchanged online. The CD also had the unintended effect of making the physical record album less valuable. CD cases were small, plastic, and annoying; the booklets wedged inside them were rarely removed; and the disks themselves had a space-age sterility that rendered them entirely charmless. By reducing the perceived value of the physical product, CDs made it easier for consumers to discard that product - in fact, getting rid of a CD collection was a great joy to many of us. The book business did not go through a digitization phase prior to the arrival of the web, so there was no supply of digital books waiting to be traded when online trading became possible. It was an entirely different situation from a technological standpoint.

The average music buyer is younger than the average book buyer. Young people have long been a primary market for popular music. Young people also tend to have the spare time, the tech savvy, the obliviousness to risk, the constrained wallets, and the passion for music required to do a whole lot of bootlegging. Books tend to be sold to older people. Older people make lousy pirates. That's another crucial reason why book publishers have been sheltered from piracy in a way that record companies weren't.

When Apple first promoted its iTunes app - this was quite a while before it got into music retailing - it used the slogan "Rip Mix Burn." Though it wouldn't admit it, it wanted people to engage in widespread copying and trading of music, because the more free digital music files that went into circulation, the more attractive its computers (and subsequently its iPods) became. (MP3s, in economic terms, were complements to Apple's core products.) That slogan never had an analogue in the book business because the history, technology, and customers of the book business were fundamentally different at the start of the digital age. People like Reid like to suggest that if record company executives had made different decisions a decade ago, the fate of their industry would have been different. I'm skeptical about that. Sure, they could have made different decisions, but I really don't think it would have changed the course of history much. They were basically screwed.

And executives in the publishing industry are probably kidding themselves if they think that they're responsible for the fact that, so far, their business hasn't gone through the wrenching changes that have affected their peers in the music business. And if they think they can use the experience of the music business as a guide to plot their own future course, they're probably kidding themselves there, too. The impending forces of disruption in the book world may resemble the forces that battered the music world, but they're different in many important ways.

|

|

Reading with Oprah |

We want to think an ebook is a book. But although an ebook is certainly related to a book, it's not a book. It's an ebook. And we don't yet know what an ebook is. We are getting some early hints, though. Oprah Winfrey dropped one just yesterday, when she announced the relaunch of her famous book club. Oprah's Book Club 2.0 is, she said, a book club for "our digital world." What's most interesting about it, at least for media prognosticators, is that each of Oprah's picks will be issued in a special ebook edition, available for Kindles, Nooks, and iPads, that will, as Julie Bosman reports, "include margin notes from Ms. Winfrey highlighting her favorite passages."

Those passages will appear as underlined text in the ebook edition, followed by an icon in the shape of an "O." Click on the text or the icon and up pops Oprah's reflection on the passage. For instance, in the first Book Club 2.0 choice, Cheryl Strayed's Wild, the following sentence is highlighted:

Of all the things I'd been skeptical about, I didn't feel skeptical about this: the wilderness had a clarity that included me.

Oprah's gloss on the sentence reads:

That may be my favorite line in the whole book. First of all, it's so beautifully constructed, and it captures what this journey was all about. She started out looking to find herself—looking for clarity—and that's exactly what happens. The essence of the book is held right there in that sentence. It means that every step was worth it. It means all the skepticism of whether this hike is the right thing or not the right thing—it all gets resolved in that sentence.

For the reader, Oprah's notes become part of the book, a new authorial voice woven into the original text. There's plenty of precedent for this, of course. Annotated and critical editions of books routinely include an overlay of marginal comments and other notes, which very much influence the reader's experience of the book. But such editions are geared for specialized audiences - students and scholars - and they tend to appear well after the original edition. Oprah's notes are different, and they point to some of the ways that ebooks may overthrow assumptions that have built up during the centuries that people have been reading bound books. For one thing, it becomes fairly easy to publish different versions of the same book, geared to different audiences or even different retailers, at the same time. We may, for example, see a proliferation of "celebrity editions," with comments from politicians, media stars, and other prominent folk. There may also be "sponsored editions," in which a company buys the right to, say, have its CEO annotate an ebook (that could be a real money-maker for authors and publishers of volumes of management advice). Writers themselves could come out with premium editions that include supplemental comments or other material - for a couple of bucks more than the standard edition. There's no reason the annotations need be limited to text, either. In future book club selections, what pops up when you click the O icon might be a video of Oprah sharing her comments. And since an ebook is in essence an application running on a networked computer, the added material could be personalized for individual readers or could be continually updated.

Because ebooks tend to sell for a much lower price than traditional hard covers, publishers will have strong incentives to try all these sorts of experiments as well as many others, particularly if the experiments have the potential to strengthen sales or open new sources of revenues. In small or large ways, the experience of reading, and of writing, will change as books are remodeled to fit their new container.

|

|

Careful what you link to |

The front page of today's New York Times serves up a cautionary tale:

On Valentine’s Day, Nick Bergus came across a link to an odd product on Amazon.com: a 55-gallon barrel of ... personal lubricant.

He found it irresistibly funny and, as one does in this age of instant sharing, he posted the link on Facebook, adding a comment: “For Valentine’s Day. And every day. For the rest of your life.”

Within days, friends of Mr. Bergus started seeing his post among the ads on Facebook pages, with his name and smiling mug shot. Facebook — or rather, one of its algorithms — had seen his post as an endorsement and transformed it into an advertisement, paid for by Amazon ...

55 gallons? That's a lot of frictionless sharing.

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/06/careful_what_you_link_to.html

|

|

Perfect silence |

I realized this morning that my last two posts share a common theme, so I thought I might as well go ahead and make a trilogy of it. To the voices of Kraus and Teleb I'll add that of the Pope:

Silence is an integral element of communication; in its absence, words rich in content cannot exist. In silence, we are better able to listen to and understand ourselves; ideas come to birth and acquire depth; we understand with greater clarity what it is we want to say and what we expect from others; and we choose how to express ourselves. By remaining silent we allow the other person to speak, to express him or herself; and we avoid being tied simply to our own words and ideas without them being adequately tested. In this way, space is created for mutual listening, and deeper human relationships become possible. It is often in silence, for example, that we observe the most authentic communication taking place between people who are in love: gestures, facial expressions and body language are signs by which they reveal themselves to each other. Joy, anxiety, and suffering can all be communicated in silence – indeed it provides them with a particularly powerful mode of expression. Silence, then, gives rise to even more active communication, requiring sensitivity and a capacity to listen that often makes manifest the true measure and nature of the relationships involved. When messages and information are plentiful, silence becomes essential if we are to distinguish what is important from what is insignificant or secondary. Deeper reflection helps us to discover the links between events that at first sight seem unconnected, to make evaluations, to analyze messages; this makes it possible to share thoughtful and relevant opinions, giving rise to an authentic body of shared knowledge. For this to happen, it is necessary to develop an appropriate environment, a kind of ‘eco-system’ that maintains a just equilibrium between silence, words, images and sounds.

(Aside to Vatican: Change the background on your site. It's very noisy.)

Making the case for silent communication has always been a tricky business, since language itself wants to make an oxymoron of the idea, but it's trickier than ever today. We've come to confuse communication, and indeed thought itself, with the exchange of explicit information. What can't be codified and transmitted, turned into data, loses its perceived value. (What code does a programmer use to render silence?) We seek ever higher bandwidth and ever lower latency, not just in our networks but in our relations with others and even in ourselves. The richness of implicit communication, of thought and emotion unmanifested in expression, comes to be seen as mere absence, as wasted bandwidth.

Whitman in a way is the most internet-friendly of the great poets. He would have made a killer blogger (though Twitter would have unmanned him). But even Whitman, I'm pretty sure, would have tired of the narrowness of so much bandwidth, would in the end have become a refugee from the Kingdom of the Explicit:

When I heard the learn’d astronomer;

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me;

When I was shown the charts and the diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them;

When I, sitting, heard the astronomer, where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon, unaccountable, I became tired and sick;

Till rising and gliding out, I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

"Unaccountable" indeed. I'm speechless.

|

|

A little more signal, a lot more noise |

I don't fully understand this excerpt from Nassim Nicholas Taleb's forthcoming book Antifragile, but I found this bit to be intriguing:

The more frequently you look at data, the more noise you are disproportionally likely to get (rather than the valuable part called the signal); hence the higher the noise to signal ratio. And there is a confusion, that is not psychological at all, but inherent in the data itself. Say you look at information on a yearly basis, for stock prices or the fertilizer sales of your father-in-law’s factory, or inflation numbers in Vladivostock. Assume further that for what you are observing, at the yearly frequency the ratio of signal to noise is about one to one (say half noise, half signal) —it means that about half of changes are real improvements or degradations, the other half comes from randomness. This ratio is what you get from yearly observations. But if you look at the very same data on a daily basis, the composition would change to 95% noise, 5% signal. And if you observe data on an hourly basis, as people immersed in the news and markets price variations do, the split becomes 99.5% noise to .5% signal. That is two hundred times more noise than signal — which is why anyone who listens to news (except when very, very significant events take place) is one step below sucker. ... Now let’s add the psychological to this: we are not made to understand the point, so we overreact emotionally to noise. The best solution is to only look at very large changes in data or conditions, never small ones.

I've long suspected, based on observations of myself as well as observations of society, that, beyond the psychological and cognitive strains produced by what we call information overload, there is a point in intellectual inquiry when adding more information decreases understanding rather than increasing it. Taleb's observation that as the frequency of information sampling increases, the amount of noise we take in expands more quickly than the amount of signal might help to explain the phenomenon, particularly if human understanding hinges as much or more on the noise-to-signal ratio of the information we take in as on the absolute amount of signal we're exposed to. Because we humans seem to be natural-born signal hunters, we're terrible at regulating our intake of information. We'll consume a ton of noise if we sense we may discover an added ounce of signal. So our instinct is at war with our capacity for making sense.

If this is indeed a problem, it's not an isolated one. We have a general tendency to believe that if x amount of something is good, then 2x must be better. This leads, for instance, to a steady increase in the average portion size of a soft drink - until the negative effects on health become so apparent that they're impossible to ignore. Even then, though, it remains difficult to moderate our personal behavior. When given the choice, we continue to order the Big Gulps.

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/05/a_little_more_signal_a_lot_mor.html

|

|

Filling all the gaps |

In a recent presentation, entrepreneur, angel, and Googler Joe Kraus provided a good overview of the costs of our "culture of distraction" and how smartphones are ratcheting those costs up. Early in the talk he shows, in stark graphical terms, how people's patterns of internet use change when they get a smartphone. Essentially, a tool becomes an environment.

For those of you who are text-biased, here's a transcript.

|

|

Workers of the world, level up! |

[Google Doodle from Nov. 30, 2011]

For my sins, I've been reading some marketing brochures - pdfs, actually - from an outfit called Lithium. Lithium is a consulting company that helps businesses design programs to take advantage of the social web, to channel the energies of online communities toward bottom lines. "We do great things and have a playful mindset while doing it," Lithium says of itself, exhibiting a characteristically innovative approach to grammar. It likes the bright colors and rounded fonts that have long been the hallmarks of Web 2.0's corporate identity program:

One of the main thrusts of Lithium's business, as the above clipping suggests, is to reduce its clients' customer service costs by tapping into the social web's free labor pool. This, according to a recent report from the Economist's Babbage blog, is called "unsourcing." Instead of paying employees or contractors to answer customers' questions or provide them with technical support, you offload the function to the customers themselves. They do the work for free, and you pocket the savings. As Babbage explains:

Some of the biggest brands in software, consumer electronics and telecoms have now found a workforce offering expert advice at a fraction of the price of even the cheapest developing nation, who also speak the same language as their customers, and not just in the purely linguistic sense. Because it is their customers themselves. "Unsourcing", as the new trend has been dubbed, involves companies setting up online communities to enable peer-to-peer support among users. ... This happens either on the company's own website or on social networks like Facebook and Twitter, and the helpers are generally not paid anything for their efforts.

If Tom Sawyer were alive today and living in Silicon Valley, he might well be bigger than Zuck.

Unsourcing reveals that the digital-sharecropping model of low-cost online production has applications beyond media creation and curation. Businesses of all stripes have opportunities to replace paid labor with play labor. Call it functional sharecropping.

As Lithium makes clear, customer-service communities don't just pop up out of nowhere. You have to cultivate them. You have to create the right platform to capture the products of the labor, and you have to offer a set of incentives that will inspire the community to do your bidding. You also have to realize that, as is typical of social networks, a tiny fraction of the members are probably going to do the bulk of the work. So the challenge is to identify your star sharecroppers (or "superfans," as Lithium calls them), entice them to contribute a good amount of time to the effort, and keep them motivated with non-monetary rewards. That's where gamification comes in. "Gamification" refers to the use of game techniques - competition, challenges, awards, point systems, "level up" advances, and the like - to get people to do what you want them to do. Lithium describes it like this:

Humans love games. There’s all kinds of math and science behind why, but the bottom line is - games are fun. Games provide an opportunity for us to enter a highly rewarding mental state where our challenges closely match our abilities. Renowned game designer, Jane McGonigal, writes that games offer us “blissful productivity” - the chance to improve, to advance, and to level up. If you’re trying to get your social customers to post product reviews, help other customers solve problems, come up with new solutions, provide sales advice, or help you innovate new products, introducing games - the chance for blissful productivity - into the experience can provide the right type of incentives that pave the way to higher, more sustained interactions.

Blissful productivity: that sounds nice, doesn't it? I mean, given the choice between bliss and a paycheck, I would go with bliss every time. Believe it or not, though, there are some critics who see gamification as manipulative and even grotesque, a debasement of the innocence of games. One of those party-poopers, Rob Horning, puts it this way:

Gamification is awful for many reasons, not least in the way it seeks to transform us into atomized laboratory rats, reduce us to the sum total of our incentivized behaviors. But it also increases the pressure to make all game playing occur within spaces subject to capture; it seeks to supply the incentives to make games not about relaxation and escape and social connection but about data generation.

Chill out already. I think people like Horning really need to have more bright colors and rounded fonts in their lives. "Games introduce addictive fun," says Lithium. And what's wrong with addictive fun when it brings both blissful productivity and demonstrable cost savings? One thing Lithium doesn't point out is that online gamification is also a great way to recruit kids into performing some free labor for your business. After all, isn't the ideal online technical support superfan a geeky, game-loving 13-year-old boy with a lot of time on his hands? And since you're paying the tyke with badges rather than cash, you can totally avoid that weird grey area of child labor.

It seems pretty clear to me that gamification-fueled unsourcing is a great breakthrough for both business and the social web. It not only allows companies to trim their head counts and cut their labor costs; it also spreads the altruistic peer-production model to more sectors of the economy and puts a little more bliss into people's lives. It's a win-win all around. Except, of course, for the chump who - n00b! - loses his job.

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/05/workers_of_the_world_level_up.html

|

|

Screenage wasteland |

In 1993, the band Cracker released a terrific album called Kerosene Hat - the opening track, "Low," was an alternative radio staple - and I became a fan. I remember checking out the group's message board on America Online at the time and being pleasantly surprised to find the two founding members - David Lowery and Johnny Hickman - making frequent postings. Lowery, who had earlier been in Camper Van Beethoven, turned out to be one of the more tech-savvy rock musicians. He'd been trained as a mathematician and was as adept with computers as he was with guitars. When the Web came along, he and his bands soon had a fairly sophisticated network of sites, hosting fan conversations, selling music, promoting gigs. In addition to playing, Lowery runs an indie label, operates a recording studio, produces records for other bands, teaches music finance at the University of Georgia, and is married to a concert promoter. He knows the business, and much of his career has been spent fighting with traditional record companies.

That's all by way of background to a remarkable talk that Lowery gave in February at the SF MusicTech Summit, a transcript of which has been posted at The Trichordist (thanks to Slashdot for the pointer). Lowery offers a heartfelt and incisive critique of the effects of the internet and, in particular, the big tech companies that now act as aggregators and mediators of music, a critique that dismantles the starry-eyed assumption that the net has liberated musicians from servitude to record companies. The net, he argues, has merely replaced the Old Boss with a New Boss, and, as it turns out, the New Boss is happy to skim money from the music business without investing any capital or sharing any risk with musicians. The starving artist is hungrier than ever.

When Napster came along, Lowery says, he immediately understood that bands would "lose sales to large-scale sharing" but he was nevertheless optimistic that "through more efficient distribution systems and disintermediation we artists would net more":

So like many other artists I embraced the new paradigm and waited for the flow of revenue to the artists to increase. It never did. In fact everywhere I look the trend seemed to be negative. Less money for touring. Less money for recording. Less money for promotion and publicity. The old days of the evil record labels started to seem less bad. It started to seem downright rosy ...

Was the old record label system better? Sadly I think the answer turns out to be yes. Things are worse. This was not really what I was expecting. I’d be very happy to be proved wrong. I mean it’s hard for me to sing the praises of the major labels. I’ve been in legal disputes with two of the three remaining major labels. But sadly I think I’m right. And the reason is quite unexpected. It’s seems the Bad Old Major Record Labels “accidentally” shared too much revenue and capital through their system of advances. Also the labels ”accidentally” assumed most of the risk. This is contrasted with the new digital distribution system where some of the biggest players assume almost no risk and share zero capital.

Lowery also points out how the centralization of traffic at massive sites like Facebook and YouTube has in recent years made it even harder for musicians to make a living. The big sites have actually been a force for re-intermediation, stealing visitors (and sales) away from band sites:

Facebook, YouTube and Twitter ate our web traffic. It started with Myspace and got worse when Facebook added band pages. Somewhere around 2008 every artist I know experienced a dramatic collapse in traffic to their websites. The Internet seems to have a tendency towards monopoly. All those social interactions that were happening on artists' websites aggregated on Facebook. Facebook pages made many bands' community pages irrelevant. ...

Most artists I know now mostly use their websites to manage their Facebook and Twitter presence. There are band-oriented [content management] services that automatically integrate with Facebook and Twitter. They turn your website news, tour dates and blog posts into Facebook events, Facebook posts and Tweets. Most websites function more as a backend control panel for your web presence. Yes, some of us sell swag and downloads on our websites but unless you are a really really popular band, or you have a major record label that can help you promote your website, it’s generally a few hundred of the most ardent fans that ever spend anytime on a band's website ...

A similar situation occurs with the process of selling music online. Our fans already have an iTunes account. They already have a credit card on file with Amazon. That small hassle of getting your credit card out of your wallet to buy music directly from the artist website is a giant hurdle that most people will not jump over.

It's a long piece, and if you're interested in the unexpected economic effects of the net on creative professions, you owe it to yourself to read it in full, whatever your views are. I'll just share a little bit more from the end:

I think I’ve demonstrated how important it was to the old system that record labels shared risk and invested capital in the creation of music. And that by doing this the record labels “accidentally” shared more revenue with the artists. But I’ve yet to explain why it is that The New Boss refuses to share risk and invest in content creation. I mean the old record labels eventually saw that it was in their long-term interest to do so.

My only explanation is that there is just something fundamentally wrong with how many in the tech industry look at the world. They are deluded somehow. Freaks. Taking no risk and paying nothing to the content creators is built into the collective psyche of the Tech industry. They do not value content. They only see THEIR services as valuable. They are the Masters of the Universe. They bring all that is good. Content magically appears on their blessed networks. ...

Not only is the New Boss worse than the Old Boss. The New Boss creeps me out.

|

|

The hierarchy of innovation |

"If you could choose only one of the following two inventions, indoor plumbing or the Internet, which would you choose?" -Robert J. Gordon

Justin Fox is the latest pundit to ring the "innovation ain't what it used to be" bell. "Compared with the staggering changes in everyday life in the first half of the 20th century," he writes, summing up the argument, "the digital age has brought relatively minor alterations to how we live." Fox has a lot of company. He points to sci-fi author Neal Stephenson, who worries that the Internet, far from spurring a great burst of creativity, may have actually put innovation "on hold for a generation." Fox also cites economist Tyler Cowen, who has argued that, recent techno-enthusiasm aside, we're living in a time of innovation stagnation. He could also have mentioned tech powerbroker Peter Thiel, who believes that large-scale innovation has gone dormant and that we've entered a technological "desert." Thiel blames the hippies:

Men reached the moon in July 1969, and Woodstock began three weeks later. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that this was when the hippies took over the country, and when the true cultural war over Progress was lost.

The original inspiration for such grousing - about progress, not about hippies - came from Robert J. Gordon, a Northwestern University economist whose 2000 paper "Does the 'New Economy' Measure Up to the Great Inventions of the Past?" included a damning comparison of the flood of inventions that occurred a century ago with the seeming trickle that we see today. Consider the new products invented in just the ten years between 1876 and 1886: internal combustion engine, electric lightbulb, electric transformer, steam turbine, electric railroad, automobile, telephone, movie camera, phonograph, linotype, roll film (for cameras), dictaphone, cash register, vaccines, reinforced concrete, flush toilets. The typewriter had arrived a few years earlier and the punch-card tabulator would appear a few years later. And then, in short order, came airplanes, radio, air conditioning, the vacuum tube, jet aircraft, television, refrigerators and a raft of other home appliances, as well as revolutionary advances in manufacturing processes. (And let's not forget The Bomb.) The conditions of life changed utterly between 1890 and 1950, observed Gordon. Between 1950 and today? Not so much.

So why is innovation less impressive today? Maybe Thiel is right, and it's the fault of hippies, liberals, and other degenerates. Or maybe it's crappy education. Or a lack of corporate investment in research. Or short-sighted venture capitalists. Or overaggressive lawyers. Or imagination-challenged entrepreneurs. Or maybe it's a catastrophic loss of mojo. But none of these explanations makes much sense. The aperture of science grows ever wider, after all, even as the commercial and reputational rewards for innovation grow ever larger and the ability to share ideas grows ever stronger. Any barrier to innovation should be swept away by such forces.

Let me float an alternative explanation: There has been no decline in innovation; there has just been a shift in its focus. We're as creative as ever, but we've funneled our creativity into areas that produce smaller-scale, less far-reaching, less visible breakthroughs. And we've done that for entirely rational reasons. We're getting precisely the kind of innovation that we desire - and that we deserve.

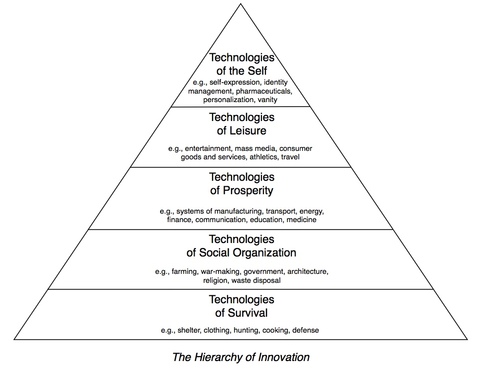

My idea - and it's a rough one - is that there's a hierarchy of innovation that runs in parallel with Abraham Maslow's famous hierarchy of needs. Maslow argued that human needs progress through five stages, with each new stage requiring the fulfillment of lower-level, or more basic, needs. So first we need to meet our most primitive Physiological needs, and that frees us to focus on our needs for Safety, and once our needs for Safety are met, we can attend to our needs for Belongingness, and then on to our needs for personal Esteem, and finally to our needs for Self-Actualization. If you look at Maslow's hierarchy as an inflexible structure, with clear boundaries between its levels, it falls apart. Our needs are messy, and the boundaries between them are porous. A caveman probably pursued self-esteem and self-actualization, to some degree, just as we today spend effort seeking to fulfill our physical needs. But if you look at the hierarchy as a map of human focus, or of emphasis, then it makes sense - and indeed seems to be born out by history. In short: The more comfortable you are, the more time you spend thinking about yourself.

If progress is shaped by human needs, then general shifts in needs would also bring shifts in the nature of technological innovation. The tools we invent would move through the hierarchy of needs, from tools that help safeguard our bodies on up to tools that allow us to modify our internal states, from tools of survival to tools of the self. Here's my crack at what the hierarchy of innovation looks like (click on the image to enlarge it):

The focus, or emphasis, of innovation moves up through five stages, propelled by shifts in the needs we seek to fulfill. In the beginning come Technologies of Survival (think fire), then Technologies of Social Organization (think cathedral), then Technologies of Prosperity (think steam engine), then technologies of leisure (think TV), and finally Technologies of the Self (think Facebook, or Prozac).

As with Maslow's hierarchy, you shouldn't look at my hierarchy as a rigid one. Innovation today continues at all five levels. But the rewards, both monetary and reputational, are greatest at the highest level (Technologies of the Self), which has the effect of shunting investment, attention, and activity in that direction. We're already physically comfortable, so getting a little more physically comfortable doesn't seem particularly pressing. We've become inward looking, and what we crave are more powerful tools for modifying our internal state or projecting that state outward. An entrepreneur has a greater prospect of fame and riches if he creates, say, a popular social-networking tool than if he creates a faster, more efficient system for mass transit. The arc of innovation, to put a dark spin on it, is toward decadence.

One of the consequences is that, as we move to the top level of the innovation hierarchy, the inventions have less visible, less transformative effects. We're no longer changing the shape of the physical world or even of society, as it manifests itself in the physical world. We're altering internal states, transforming the invisible self. Not surprisingly, when you step back and take a broad view, it looks like stagnation - it looks like nothing is changing very much. That's particularly true when you compare what's happening today with what happened a hundred years ago, when our focus on Technologies of Prosperity was peaking and our focus on Technologies of Leisure was also rapidly increasing, bringing a highly visible transformation of our physical circumstances.

If the current state of progress disappoints you, don't blame innovation. Blame yourself.

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/05/the_hierarchy_of_innovation.html

|

|

Social production guru, heal thyself |

I was pleased to see that Yochai Benkler launched a blog on Monday - and, since the first (and as yet only) post was a response to my claim of victory in the Carr-Benkler Wager, I think I can even take a bit of credit for inspiring the professor to join the hurly-burly of the blogosphere. Welcome, Yochai! Long may you blog!

I fear, however, that no one explained to Yochai the concept of Comments. You see, on Monday I scribbled out a fairly long reply to his post, and submitted it through his comment form. I was hoping, as a long-time social producer myself, to spur a good, non-price-incentivized online conversation. But, now five days later, my comment has not appeared on his blog. In fact, no comments have appeared. Perhaps it's a technical glitch, but since Yochai's blog is one of many Harvard Law blogs, I have to think that the Comment form is working and that the fault lies with the blogger. (I even resubmitted my comment, just in case there was a glitch with the first submission.)

Memo to Yochai: social production begins at home.

Fortunately, I saved a copy of my comment. So, while waiting for Yochai to get around to tending his comment stream, I will post it here:

Yochai,

Thanks for your considered reply. I'm sure you'll be shocked to discover that I disagree with your claim that you’ve won our wager. I think you're doing more than a little cherry-picking here, both in choosing categories and in defining categories. Most important, you're shortchanging the actual content that circulates online, which I would consider the most important factor in diagnosing the nature of production. For example, you highlight "music distribution" and "music funding," but you ignore the music itself (the important thing), which continues to be dominated by price-incentivized production - even on p-to-p networks, the vast majority of what's traded is music produced by paid professionals. The same goes, for example, for news reporting, where peer production is a minuscule slice of the pie. Where is the great expansion of the peer production model that you promised six years ago? Where are all the Wikipedias in other realms of informational goods? The fact is, the spread of social production just hasn't happened. Even open-source software – your primary example of social production - has moved away from peer production and toward price-incentivized production. I don’t say that this is necessarily a good thing, I just say that it’s the reality of what’s happening.

Here's my (quick and dirty) alternative rundown of whether the most influential sites in major categories of online activity are generally characterized by price-incentivized production (pi) or peer production (pp):

News reporting/writing: pi (relatively little pp)

News opinion: pi (Huff Post has mix, but shifting toward more pi, both by Huff Post paid staff and for others writing as paid employees of other organizations; other popular news opinion sites are dominantly pi)

News story discovery/aggregation: unclear (are Twitter, Reddit, Stumbleupon et al. really the most influential, or are they secondary to the editorial decision-making by sites like NY Times, WSJ, BBC, Guardian, Daily Mail, The Atlantic, and other traditional papers and magazines? I don't think this is an easy one to figure out. My own sense is that traditional news organizations play a dominant role in shaping what news is seen and read online, though I acknowledge the importance of social production in the sharing of links to stories and the incorporation of social-production tools at traditional newspaper and magazine sites.)

General (non-news) web content discovery/aggregation: pp

Blogging: pi (big change from 2006)

Other writing: pi

Music (creation): pi

Music (discovery/aggregation): difficult to say, as a lot of sites (eg, YouTube) have mixed models, but I would give the edge to pi based on dominance of big retailing sites (iTunes, Amazon), big streaming sites (Spotify, Rhapsody), and artist and record company sites. Certainly since 2006, there's been a shift toward commercial sites.

Photographs: pp

Video (creation): pi (with all due respect to YouTube amateurs, professionally produced TV shows, TV show clips, movies, movie clips, music videos, advertisements, now dominate online viewing through YouTube, Hulu, Netfllix, tv sites, newspaper sites, e.g. WSJ video, professional blog sites with video components, etc.

Radio/podcasting: pi

Recipes: pi

Charitable giving: pi (i.e., operated by paid staff)

Reviews: pp (a big, diffuse category that could be broken up in many ways, but I think overall pp dominates in use, if not influence)

How-to advice: pi

Encyclopedias: pp

E-books: pi (that goes for even self-published e-books)

Apps: pi

Games: pi

Advertising: pi (except classified advertising, which goes pp thanks to Craigslist)

Education and training: pi

Weather reports and forecasts: pi

Greeting cards and invitations: pi

Scholarship: pi

Political campaigns: pi (the social-networking hype that attended the first Obama campaign turned out to be overblown; campaigns continue to be professionally managed operations)

Pornography: pi (again, with all due respect to the intrepid amateurs)

The fact is that peer production hasn't revolutionized models of content production online, even if we grant (as I do) that peer production continues to play an important (and occasionally dominant) role in some areas.

Social networking? Yes, social networking is, by definition, social networking, but even in what we define as social networking, do you really dispute that price-incentivized content is not playing an ever larger (rather than smaller) role? Here, to illustrate, are the Top 20 most popular Facebook pages as of the end of 2010 (most recent stats I could find):

1. Texas Hold'em Poker (Zynga page)

2. Facebook

3. Michael Jackson

4. Lady Gaga

5. Family Guy

6. YouTube

7. Eminem

8. Vin Diesel

9. Twilight Saga

10. Starbucks

11. Megan Fox

12. South Park

13. Coca-Cola

14. House (TV show)

15. Linkin Park

16. Barack Obama

17. Lil Wayne

18. Justin Bieber

19. Mafia Wars (Zynga)

20. Cristiano RonaldoOf the ten most viewed YouTube videos of all time (as of this month), nine are professional productions and only one (yes, it's "Charlie Bit My Finger") is a non-price-incentivized production. Even Twitter is far from a pure p-to-p site; many contributors contribute as part of their jobs. I think what we’re learning – and it’s hardly a surprise – is that when a for-profit corporation operates a social network, it becomes steadily more commercialized.

I don't expect that I've convinced you that I've won the bet, but it sure would be nice if you would acknowledge the web's shift, since 2006, to a medium ever more dominated by professionally produced content and ever more controlled by commercial interests, for better or for worse.

And welcome to blogging,

Nick

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/05/social_production_guru_heal_th.html

|

|

FarmVille: a Gothic fantasia |

"You built it yourself, with play-labor, but politically it’s a slum."

-Bruce Sterling

1

Hardware is a problem. It wears out. It breaks down. It is subject to physical forces. It is subject to entropy. It deteriorates. It decays. It fails. The moment of failure can't be predicted, but what can be predicted is that the moment will come. Assemblies of atoms are doomed. Worse yet, the more components incorporated into a physical system - the more subassemblies that make up the assembly - the more points of failure the apparatus has and the more fragile it becomes.

This is an engineering problem. This is also a metaphysical problem.

2

One of Google's great innovations in building the data centers that run its searches was to use software as a means of isolating each component of the system and hence of separating component failure from system failure. The networking software senses a component failure (a dying hard drive, say) and immediately bypasses the component, routing the work to another, healthy piece of hardware in the system. No single component matters; each is entirely dispensable and entirely disposable. Maintaining the system, at the hardware level, becomes a simple process of replacing failed parts with fresh ones. You hire a low-skilled worker, or make a robot, and when a component dies, the worker, or the robot, swaps it out with a good one.

Such a system requires smart software. It also requires cheap parts.

3

Executing an algorithm with a physical system is like putting a mind into a body.

4

Bruce Sterling gave an interesting speech at a conference in 2009. He drew a distinction between two lifestyles that form the poles of our emerging "cultural temperament." On the one end - the top end - you have Gothic High-Tech:

In Gothic High-Tech, you’re Steve Jobs. You’ve built an iPhone which is a brilliant technical innovation, but you also had to sneak off to Tennessee to get a liver transplant because you’re dying of something secret and horrible. And you’re a captain of American industry. You’re not some General Motors kinda guy. On the contrary, you’re a guy who’s got both hands on the steering wheel of a functional car. But you’re still Gothic High-Tech because death is waiting. And not a kindly death either, but a sinister, creeping, tainted wells of Silicon Valley kind of Superfund thing that steals upon you month by month, and that you have to hide from the public and from the bloggers and from the shareholders.

And then there's the other end - the bottom end - which Sterling calls Favela Chic. These are the multitudinous "play-laborers" of the virtual realm.

What is Favela Chic? Favela Chic is when you have lost everything material, everything you built and everything you had, but you’re still wired to the gills! And really big on Facebook. That’s Favela Chic. You lost everything, you have no money, you have no career, you have no health insurance, you’re not even sure where you live, you don’t have children, and you have no steady relationship or any set of dependable friends. And it’s hot. It’s a really cool place to be.

The Favela Chic worship the Gothic High-Tech because the Gothic High-Tech have perfected unreality. They have escaped the realm of "the infrastructure" and have positioned themselves "in the narrative," the stream that flows forever, unimpeded. They are avatars: software without apparatus, mind without body.

Except when a part fails.

5

H. G. Wells, in his Gothic novella "The Time Machine," used different terms. The Gothic High-Tech he called Morlocks. The Favela Chic he called Eloi. Of course Wells was writing not in a time of virtualization but in a time of industrialization.

About eight or nine in the morning I came to the same seat of yellow metal from which I had viewed the world upon the evening of my arrival. I thought of my hasty conclusions upon that evening and could not refrain from laughing bitterly at my confidence. Here was the same beautiful scene, the same abundant foliage, the same splendid palaces and magnificent ruins, the same silver river running between its fertile banks. The gay robes of the beautiful people moved hither and thither among the trees. Some were bathing in exactly the place where I had saved Weena, and that suddenly gave me a keen stab of pain. And like blots upon the landscape rose the cupolas above the ways to the Under-world. I understood now what all the beauty of the Over-world people covered. Very pleasant was their day, as pleasant as the day of the cattle in the field. Like the cattle, they knew of no enemies and provided against no needs. And their end was the same.

6

The young, multibillionaire technologist is left with only two avocations: space travel and the engineering of immortality. Both are about escaping the gravity of the situation.

There are two apparent ways to sidestep death. You can virtualize the apparatus, freeing the mind from the body. But before you can do that, you need to figure out the code. And, alas, when it comes to the human being, we are still a long way from figuring out the code. Disembodiment is not imminent. Or you can take the Google route and figure out a way to quickly bypass the failed component, whether it's the heart or the kidney, the pancreas or the liver. In time, we may figure out a may to fabricate the essential components of our bodies - to create an unlimited supply - but that eventuality, too, is not imminent. So we are left, for the time being, with transplantation, with the harvesting of good components from failed systems and the use of those components to replace the failed components of living systems.

The Gothic High-Tech, who cannot abide death, face a problem here: the organ donation system is largely democratic; it can't be easily gamed by wealth. A rich person may be able to travel somewhere that has shorter lines - Tennessee, perhaps - but he can't jump to the head of the line. So the challenge becomes one of increasing the supply, of making dear components cheap.

7

A week ago, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, in a move that he said was inspired by the experience of his friend Steve Jobs, announced that Facebook was introducing a new feature that would make it easy for members to identify themselves as organ donors. Should Zuckerberg's move increase the supply of organs, it will save many lives and alleviate much suffering. We should all be grateful. Dark dreams of the future are best left to science-fiction writers.

http://www.roughtype.com/2012/05/farmville_a_gothic_fantasia.html

|

|

| Страницы: [1] Календарь |