-Метки

-Музыка

- Roxette - Listen To Your Heart (ф-но)

- Слушали: 118 Комментарии: 0

- james blunt-tears and rain

- Слушали: 93 Комментарии: 0

- Keane - What a wonderful world

- Слушали: 8 Комментарии: 0

- Louis Armstrong " Blueberry Hill"

- Слушали: 1032 Комментарии: 0

- Би-2 Серебро

- Слушали: 132 Комментарии: 0

-Подписка по e-mail

-Постоянные читатели

-Статистика

Без заголовка |

Chapter Twelve.

Cry of the Hunters

Ralph lay in a covert, wondering about his wounds. The bruised flesh was inches in diameter over his right ribs, with a swollen and bloody scar where the spear had hit him. His hair was full of dirt and tapped like the tendrils of a creeper. All over he was scratched and bruised from his flight through the forest. By the time his breathing was normal again, he had worked out that bathing these injuries would have to wait. How could you listen for naked feet if you were splashing in water? How could you be safe by the little stream or on the open beach?

Ralph listened. He was not really far from the Castle Rock, and during the first panic he had thought he heard sounds of pursuit But the hunters had only sneaked into the fringes of the greenery, retrieving spears perhaps, and then had rushed back to the sunny rock as if terrified of the darkness under the leaves. He had even glimpsed one of them, striped brown, black, and red, and had judged that it was Bill. But really, thought Ralph, this was not Bill. This was a savage whose image refused to blend with that ancient picture of a boy in shorts and shirt.

The afternoon died away; the circular spots of sunlight moved steadily over green fronds and brown fiber but no sound came from behind the rock. At last Ralph wormed out of the ferns and sneaked forward to the edge of that impenetrable thicket that fronted the neck of land. He peered with elaborate caution between branches at the edge and could see Robert sitting on guard at the top of the cliff. He held a spear in his left hand and was tossing up a pebble and catching it again with the right. Behind him a column of smoke rose thickly, so that Ralph’s nostrils flared and his mouth dribbled. He wiped his nose and mouth with the back of his hand and for the first time since the morning felt hungry. The tribe must be sitting round the gutted pig, watching the fat ooze and burn among the ashes. They would be intent

Another figure, an unrecognizable one, appeared by Robert and gave him something, then turned and went back behind the rock. Robert laid his spear on the rock beside him and began to gnaw between his raised hands. So the feast was beginning and the watchman had been given his portion.

Ralph saw that for the time being he was safe. He limped away through the fruit trees, drawn by the thought of the poor food yet bitter when he remembered the feast. Feast today, and then tomorrow…

He argued unconvincingly that they would let him alone, perhaps even make an outlaw of him. But then the fatal unreasoning knowledge came to him again. The breaking of the conch and the deaths of Piggy and Simon lay over the island like a vapor. These painted savages would go further and further. Then there was that indefinable connection between himself and Jack; who therefore would never let him alone; never.

He paused, sun-flecked, holding up a bough, prepared to duck under it A spasm of terror set him shaking and he cried aloud.

“No. They’re not as bad as that. It was an accident.”

He ducked under the bough, ran clumsily, then stopped and listened.

He came to the smashed acres of fruit and ate greedily. He saw two littluns and, not having any idea of his own appearance, wondered why they screamed and ran.

When he had eaten he went toward the beach. The sunlight was slanting now into the palms by the wrecked shelter. There was the platform and the pool. The best thing to do was to ignore this leaden feeling about the heart and rely on their common sense, their daylight sanity. Now that the tribe had eaten, the thing to do was to try again. And anyway, he couldn’t stay here all night in an empty shelter by the deserted platform. His flesh crept and he shivered in the evening sun. No fire; no smoke; no rescue. He turned and limped away through the forest toward Jack’s end of the island.

The slanting sticks of sunlight were lost among the branches. At length he came to a clearing in the forest where rock prevented vegetation from growing. Now it was a pool of shadows and Ralph nearly flung himself behind a tree when he saw something standing in the center; but then he saw that the white face was bone and that the pig’s skull grinned at him from the top of a stick. He walked slowly into the middle of the clearing and looked steadily at the skull that gleamed as white as ever the conch had done and seemed to jeer at him cynically. An inquisitive ant was busy in one of the eye sockets but otherwise the thing was lifeless.

Or was it?

Little prickles of sensation ran up and down his back. He stood, the skull about on a level with his face, and held up his hair with two hands. The teeth grinned, the empty sockets seemed to hold his gaze masterfully and without effort.

What was it?

The skull regarded Ralph like one who knows all the answers and won’t tell. A sick fear and rage swept him. Fiercely he hit out at the filthy thing in front of him that bobbed like a toy and came back, still grinning into his face, so that he lashed and cried out in loathing. Then he was licking his bruised knuckles and looking at the bare stick, while the skull lay in two pieces, its grin now six feet across. He wrenched the quivering stick from the crack and held it as a spear between him and the white pieces. Then he backed away, keeping his face to the skull that lay grinning at the sky.

When the green glow had gone from the horizon and night was fully accomplished, Ralph came again to the thicket in front of the Castle Rock. Peeping through, he could see that the height was still occupied, and whoever it was up there had a spear at the ready.

He knelt among the shadows and felt his isolation bitterly. They were savages it was true; but they were human, and the ambushing fears of the deep night were coming on.

Ralph moaned faintly. Tired though he was, he could not relax and fall into a well of sleep for fear of the tribe. Might it not be possible to walk boldly into the fort, say—”I’ve got pax,” laugh lightly and sleep among the others? Pretend they were still boys, schoolboys who had said, “Sir, yes, Sir”—and worn caps? Daylight might have answered yes; but darkness and the horrors of death said no. Lying there in the darkness, he knew he was an outcast.

“‘Cos I had some sense.”

He rubbed his cheek along his forearm, smelling the acrid scent of salt and sweat and the staleness of dirt. Over to the left, the waves of ocean were breathing, sucking down, then boiling back over the rock.

There were sounds coming from behind the Castle Rock Listening carefully, detaching his mind from the swing of the sea, Ralph could make out a familiar rhythm.

“Kill the beast! Cut his throat! Spill his blood!”

The tribe was dancing. Somewhere on the other side of this rocky wall there would be a dark circle, a glowing fire, and meat. They would be savoring food and the comfort of safety.

A noise nearer at hand made him quiver. Savages were clambering up the Castle Rock, right up to the top, and he could hear voices. He sneaked forward a few yards and saw the shape at the top of the rock change and enlarge. There were only two boys on the island who moved or talked like that.

Ralph put his head down on his forearms and accepted this new fact like a wound. Samneric were part of the tribe now. They were guarding the Castle Rock against him. There was no chance of rescuing them and building up an outlaw tribe at the other end of the island. Samneric were savages like the rest; Piggy was dead, and the conch smashed to powder.

At length the guard climbed down. The two that remained seemed nothing more than a dark extension of the rock. A star appeared behind them and was momentarily eclipsed by some movement.

Ralph edged forward, feeling his way over the uneven surface as though he were bund. There were miles of vague water at his right and the restless ocean lay under his left hand, as awful as the shaft of a pit. Every minute the water breathed round the death rock and flowered into a field of whiteness. Ralph crawled until he found the ledge of the entry in his grasp. The lookouts were immediately above him and he could see the end of a spear projecting over the rock.

He called very gently.

“Samneric—”

There was no reply. To carry he must speak louder; and this would rouse those striped and inimical creatures from their feasting by the fire. He set his teeth and started to climb, finding the holds by touch. The stick that had supported a skull hampered him but he would not be parted from his only weapon. He was nearly level with the twins before he spoke again.

“Samneric—”

He heard a cry and a flurry from the rock. The twins had grabbed each other and were gibbering.

“It’s me. Ralph.”

Terrified that they would run and give the alarm, he hauled himself up until his head and shoulders stuck over the top. Far below his armpit he saw the luminous flowering round the rock.

“It’s only me. Ralph.”

At length they bent forward and peered in his face.

“We thought it was—”

“—we didn’t know what it was—”

“—we thought—”

Memory of their new and shameful loyalty came to them. Eric was silent but Sam tried to do his duty.

“You got to go, Ralph. You go away now—”

He wagged his spear and essayed fierceness.

“You shove off. See?”

Eric nodded agreement and jabbed his spear in the air. Ralph leaned on his arms and did not go.

“I came to see you two.”

His voice was thick. His throat was hurting him now though it had received no wound.

“I came to see you two—”

Words could not express the dull pain of these things. He fell silent, while the vivid stars were spilt and danced all ways.

Sam shifted uneasily.

“Honest, Ralph, you’d better go.”

Ralph looked up again.

“You two aren’t painted. How can you—? If it were light—”

If it were light shame would burn them at admitting these things. But the night was dark. Eric took up; and then the twins started their antiphonal speech.

“You got to go because it’s not safe—”

“—they made us. They hurt us—”

“Who? Jack?”

“Oh no—”

They bent to him and lowered their voices.

“Push off, Ralph—’

“—it’s a tribe—”

“—they made us—”

“—we couldn’t help it—”

When Ralph spoke again his voice was low, and seemed breathless.

“What have I done? I liked him—and I wanted us to be rescued—”

Again the stars spilled about the sky. Eric shook his head, earnestly.

“Listen, Ralph. Never mind what’s sense. That’s gone—”

“Never mind about the chief—”

“—you got to go for your own good.”

“The chief and Roger—”

“—yes, Roger—”

“They hate you, Ralph. They’re going to do you.”

“They’re going to hunt you tomorrow.”

“But why?”

“I dunno. And Ralph, Jack, the chief, says it’ll be dangerous—”

“—and we’ve got to be careful and throw our spears like at a pig.”

“We’re going to spread out in a line across the island—”

“—we’re going forward from this end—”

“—until we find you.”

“We’ve got to give signals like this.”

Eric raised his head and achieved a faint ululation by beating on his open mouth. Then he glanced behind him nervously.

“Like that—”

“—only louder, of course.”

“But I’ve done nothing,” whispered Ralph, urgently. I only wanted to keep up a fire!”

He paused for a moment, thinking miserably of the morrow. A matter of overwhelming importance occurred to him.

“What are you—?”

He could not bring himself to be specific at first; but then fear and loneliness goaded him.

“When they find me, what are they going to do?” The twins were silent. Beneath him, the death rock flowered again.

“What are they—oh God! I’m hungry—”

The towering rock seemed to sway under him.

“Well—what—?”

The twins answered his question indirectly.

“You got to go now, Ralph.”

“For your own good.”

“Keep away. As far as you can.”

“Won’t you come with me? Three of us—we’d stand a chance.”.

After a moment’s silence, Sam spoke in a strangled voice.

“You don’t know Roger. He’s a terror.”

“And the chief—they’re both—”

“—terrors—”

“—only Roger—”

Both boys froze. Someone was climbing toward them from the tribe.

“He’s coming to see if we’re keeping watch. Quick, Ralph!”

As he prepared to let himself down the cliff, Ralph snatched at the last possible advantage to be wrung out of this meeting.

“I’ll lie up close; in that thicket down there,” he whispered, “so keep them away from it. They’ll never think to took so close—”

The footsteps were still some distance away.

“Sam—I’m going to be all right, aren’t I?”

The twins were silent again.

“Here!” said Sam suddenly. “Take this—”

Ralph felt a chunk of meat pushed against him and grabbed it.

“But what are you going to do when you catch me?”

Silence above. He sounded silly to himself. He lowered himself down the rock.

“What are you going to do—?”

From the top of the towering rock came the incomprehensible reply.

“Roger sharpened a stick at both ends.”

Roger sharpened a stick at both ends. Ralph tried to attach a meaning to this but could not. He used all the bad words he could think of in a fit of temper that passed into yawning. How long could you go without sleep? He yearned for a bed and sheets—but the only whiteness here was the slow spilt milk, luminous round the rock forty feet below, where Piggy had fallen. Piggy was everywhere, was on this neck, was become terrible in darkness and death. If Piggy were to come back now out of the water, with his empty head—Ralph whimpered and yawned like a littlun. The stick in his hand became a crutch on which he reeled.

Then he tensed again. There were voices raised on the top of the Castle Rock. Samneric were arguing with someone. But the ferns and the grass were near. That was the place to be in, hidden, and next to the thicket that would serve for tomorrow’s hide-out. Here—and his hands touched grass—was a place to be in for the night, not far from the tribe, so that if the horrors of the supernatural emerged one could at least mix with humans for the time being, even if it meant…

What did it mean? A stick sharpened at both ends. What was there in that? They had thrown spears and missed; all but one. Perhaps they would miss next time, too.

He squatted down in the tall grass, remembered the meat that Sam had given him, and began to tear at it ravenously. While he was eating, he heard fresh noises—cries of pain from Samneric, cries of panic, angry voices. What did it mean? Someone besides himself was in trouble, for at least one of the twins was catching it. Then the voices passed away down the rock and he ceased to think of them. He felt with his hands and found cool, delicate fronds backed against the thicket. Here then was the night’s lair. At first light he would creep into the thicket, squeeze between the twisted stems, ensconce himself so deep that only a crawler like himself could come through, and that crawler would be jabbed. There he would sit, and the search would pass him by, and the cordon waver on, ululating along the island, and he would be free.

He pulled himself between the ferns, tunneling in. He laid the stick beside him, and huddled himself down in the blackness. One must remember to wake at first light, in order to diddle the savages—and he did not know how quickly sleep came and hurled him down a dark interior slope.

He was awake before his eyes were open, listening to a noise that was near. He opened an eye, found the mold an inch or so from his face and his fingers gripped into it, light filtering between the fronds of fern. He had just time to realize that the age-long nightmares of falling and death were past and that the morning was come, when he heard the sound again. It was an ululation over by the seashore—and now the next savage answered and the next. The cry swept by him across the narrow end of the island from sea to lagoon, like the cry of a flying bird. He took no time to consider but grabbed his sharp stick and wriggled back among the ferns. Within seconds he was worming his way into the thicket; but not before he had glimpsed the legs of a savage coming toward him. The ferns were thumped and beaten and he heard legs moving in the long grass. The savage, whoever he was, ululated twice; and the cry was repeated in both directions, then died away. Ralph crouched still, tangled in the ferns, and for a time he heard nothing.

At last he examined the thicket itself. Certainly no one could attack him here—and moreover he had a stroke of luck. The great rock that had killed Piggy had bounded into this thicket and bounced there, right in the center, making a smashed space a few feet in extent each way. When Ralph had wriggled into this he felt secure, and clever. He sat down carefully among the smashed stems and waited for the hunt to pass. Looking up between the leaves he caught a glimpse of something red. That must be the top of the Castle Rock, distant and unmenacing. He composed himself triumphantly, to hear the sounds of the hunt dying away.

Yet no one made a sound; and as the minutes passed, in the green shade, his feeling of triumph faded.

At last he heard a voice—Jack’s voice, but hushed.

“Are you certain?”

The savage addressed said nothing. Perhaps he made a gesture.

Roger spoke.

“If you’re fooling us—”

Immediately after this, there came a gasp, and a squeal of pain. Ralph crouched instinctively. One of the twins was there, outside the thicket, with Jack and Roger.

“You’re sure he meant in there?”

The twin moaned faintly and then squealed again.

“He meant he’d hide in there?”

“Yes—yes—oh—!”

Silvery laughter scattered among the trees.

So they knew.

Ralph picked up his stick and prepared for battle. But what could they do? It would take them a week to break a path through the thicket; and anyone who wormed his way in would be helpless. He felt the point of his spear with his thumb and grinned without amusement Whoever tried that would be stuck, squealing like a pig.

They were going away, back to the tower rock. He could hear feet moving and then someone sniggered. There came again that high, bird-like cry that swept along the line, So some were still watching for him; but some—?

There was a long, breathless silence. Ralph found that he had bark in his mouth from the gnawed spear. He stood and peered upwards to the Castle Rock.

As he did so, he heard Jack’s voice from the top.

“Heave! Heave! Heave!”

The red rock that he could see at the top of the cliff vanished like a curtain, and he could see figures and blue sky. A moment later the earth jolted, there was a rushing sound in the air, and the top of the thicket was cuffed as with a gigantic hand. The rock bounded on, thumping and smashing toward the beach, while a shower of broken twigs and leaves fell on him. Beyond the thicket, the tribe was cheering.

Silence again.

Ralph put his fingers in his mouth and bit them. There was only one other rock up there that they might conceivably move; but that was half as big as a cottage, big as a car, a tank. He visualized its probable progress with agonizing clearness—that one would start slowly, drop from ledge to ledge, trundle across the neck like an outsize steam roller.

“Heave! Heave! Heave!”

Ralph put down his spear, then picked it up again. He pushed his hair back irritably, took two hasty steps across the little space and then came back. He stood looking at the broken ends of branches.

Still silence.

He caught sight of the rise and fall of his diaphragm and was surprised to see how quickly he was breathing. Just left of center his heart-beats were visible. He put the spear down again.

“Heave! Heave! Heave!”

A shrill, prolonged cheer.

Something boomed up on the red rock, then the earth jumped and began to shake steadily, while the noise as steadily increased. Ralph was shot into the air, thrown down, dashed against branches. At his right hand, and only a few feet away, the whole thicket bent and the roots screamed as they came out of the earth together. He saw something red that turned over slowly as a mill wheel. Then the red thing was past and the elephantine progress diminished toward the sea.

Ralph knelt on the plowed-up soil, and waited for the earth to come back. Presently the white, broken stumps, the split sticks and the tangle of the thicket refocused. There was a kind of heavy feeling in his body where he had watched his own pulse.

Silence again.

Yet not entirely so. They were whispering out there; and suddenly the branches were shaken furiously at two places on his right. The pointed end of a stick appeared. In panic, Ralph thrust his own stick through the crack and struck with all his might.

“Aaa-ah!”

His spear twisted a little in his hands and then he withdrew it again.

“Ooh-ooh—”

Someone was moaning outside and a babble of voices rose. A fierce argument was going on and the wounded savage kept groaning. Then when there was silence, a single voice spoke and Ralph decided that it was not Jack’s.

“See? I told you—he’s dangerous.”

The wounded savage moaned again.

What else? What next?

Ralph fastened his hands round the chewed spear and his hair fell. Someone was muttering, only a few yards away toward the Castle Rock. He heard a savage say “No!” in a shocked voice; and then there was suppressed laughter. He squatted back on his heels and showed his teeth at the wall of branches. He raised his spear, snarled a little, and waited.

Once more the invisible group sniggered. He heard a curious trickling sound and then a louder crepitation as if someone were unwrapping great sheets of cellophane. A stick snapped and he stifled a cough. Smoke was seeping through the branches in white and yellow wisps, the patch of blue sky overhead turned to the color of a storm cloud, and then the smoke billowed round him.

Someone laughed excitedly, and a voice shouted.

“Smoke!”

He wormed his way through the thicket toward the forest, keeping as far as possible beneath the smoke. Presently he saw open space, and the green leaves of the edge of the thicket. A smallish savage was standing between him and the rest of the forest, a savage striped red and white, and carrying a spear. He was coughing and smearing the paint about his eyes with the back of his hand as he tried to see through the increasing smoke. Ralph launched himself like a cat; stabbed, snarling, with the spear, and the savage doubled up. There was a shout from beyond the thicket and then Ralph was running with the swiftness of fear through the undergrowth. He came to a pig-run, followed it for perhaps a hundred yards, and then swerved off. Behind him the ululation swept across the island once more and a single voice shouted three times. He guessed that was the signal to advance and sped away again, till his chest was like fire. Then he flung himself down under a bush and waited for a moment till his breathing steadied. He passed his tongue tentatively over his teeth and lips and heard far off the ululation of the pursuers.

There were many things he could do. He could climb a tree; but that was putting all his eggs in one basket. If he were detected, they had nothing more difficult to do than wait.

If only one had time to think!

Another double cry at the same distance gave him a clue to their plan. Any savage balked in the forest would utter the double shout and hold up the line till he was free again. That way they might hope to keep the cordon unbroken right across the island. Ralph thought of the boar that had broken through them with such ease. If necessary, when the chase came too close, he could charge the cordon while it was still thin, burst through, and run back. But run back where? The cordon would turn and sweep again. Sooner or later he would have to sleep or eat—and then he would awaken with hands clawing at him; and the hunt would become a running down.

What was to be done, then? The tree? Burst the line like a boar? Either way the choice was terrible.

A single cry quickened his heart-beat and, leaping up, be dashed away toward the ocean side and the thick jungle till he was hung up among creepers; he stayed there for a moment with his calves quivering. If only one could have quiet, a long pause, a time to think!

And there again, shrill and inevitable, was the ululation sweeping across the island. At that sound he shied like a horse among the creepers and ran once more till he was panting. He flung himself down by some ferns. The tree, or the charge? He mastered his breathing for a moment, wiped his mouth, and told himself to be calm. Samneric were somewhere in that line, and hating it. Or were they? And supposing, instead of them, he met the chief, or Roger who carried death in his hands?

Ralph pushed back his tangled hair and wiped the sweat out of his best eye. He spoke aloud.

“Think.”

What was the sensible thing to do?

There was no Piggy to talk sense. There was no solemn assembly for debate nor dignity of the conch.

“Think.”

Most, he was beginning to dread the curtain that might waver in his brain, blacking out the sense of danger, making a simpleton of him.

A third idea would be to hide so well that the advancing line would pass without discovering him.

He jerked his head off the ground and listened. There was another noise to attend to now, a deep grumbling noise, as though the forest itself were angry with him, a somber noise across which the ululations were scribbled excruciatingly as on slate. He knew he had heard it before somewhere, but had no time to remember.

Break the line.

A tree.

Hide, and let them pass.

A nearer cry stood him on his feet and immediately he was away again, running fast among thorns and brambles. Suddenly he blundered into the open, found himself again in that open space—and there was the fathom-wide grin of the skull, no longer ridiculing a deep blue patch of sky but jeering up into a blanket of smoke. Then Ralph was running beneath trees, with the grumble of the forest explained. They had smoked him out and set the island on fire.

Hide was better than a tree because you had a chance of breaking the line if you were discovered.

Hide, then.

He wondered it a pig would agree, and grimaced at nothing. Find the deepest thicket, the darkest hole on the island, and creep in. Now, as he ran, he peered about him. Bars and splashes of sunlight flitted over him and sweat made glistening streaks on his dirty body. The cries were far now, and faint.

At last he found what seemed to him the right place, though the decision was desperate. Here, bushes and a wild tangle of creeper made a mat that kept out all the light of the sun. Beneath it was a space, perhaps a foot high, though it was pierced everywhere by parallel and rising stems. If you wormed into the middle of that you would be five yards from the edge, and hidden, unless the savage chose to lie down and look for you; and even then, you would be in darkness—and if the worst happened and he saw you, then you had a chance to burst out at him, fling the whole line out of step and double back.

Cautiously, his stick trailing behind him, Ralph wormed between the rising stems. When he reached the middle of the mat he lay and listened.

The fire was a big one and the drum-roll that he had thought was left so far behind was nearer. Couldn’t a fire outrun a galloping horse? He could see the sun-splashed ground over an area of perhaps fifty yards from where he lay, and as he watched, the sunlight in every patch blinked at him. This was so like the curtain that flapped in his brain that for a moment he thought the blinking was inside him. But then the patches blinked more rapidly, dulled and went out, so that he saw that a great heaviness of smoke lay between the island and the sun.

If anyone peered under the bushes and chanced to glimpse human flesh it might be Samneric who would pretend not to see and say nothing. He laid his cheek against the chocolate-colored earth, licked his dry lips and closed his eyes. Under the thicket, the earth was vibrating very slightly; or perhaps there was a sound beneath the obvious thunder of the fire and scribbled ululations that was too low to hear.

Someone cried out. Ralph jerked his cheek off the earth and looked into the dulled light. They must be near now, he thought, and his chest began to thump. Hide, break the line, climb a tree—which was the best after all? The trouble was you only had one chance.

Now the fire was nearer; those volleying shots were great limbs, trunks even, bursting. The fools! The fools! The fire must be almost at the fruit trees—what would they eat tomorrow?

Ralph stirred restlessly in his narrow bed. One chanced nothing! What could they do? Beat him? So what? Kill him? A stick sharpened at both ends.

The cries, suddenly nearer, jerked him up. He could see a striped savage moving hastily out of a green tangle, and coming toward the mat where he hid, a savage who carried a spear. Ralph gripped his fingers into the earth. Be ready now, in case.

Ralph fumbled to hold his spear so that it was point foremost; and now he saw that the stick was sharpened at both ends.

The savage stopped fifteen yards away and uttered his cry.

Perhaps he can hear my heart over the noises of the fire. Don’t scream. Get ready.

The savage moved forward so that you could only see him from the waist down. That was the butt of his spear. Now you could see him from the knee down. Don’t scream. A herd of pigs came squealing out of the greenery behind the savage and rushed away into the forest. Birds were screaming, mice shrieking, and a little hopping thing came under the mat and cowered.

Five yards away the savage stopped, standing right by the thicket, and cried out. Ralph drew his

|

|

Понравилось: 35 пользователям

Без заголовка |

Автор текста: Иван Дудин

Автор музыки: Колпаков Александр

Воспоминания похожи, на очень грустные стихи

В забытой сумочке из кожи, пылятся Польские духи.

Таится в маленьком флаконе, не только нежность Польских роз.

Огонь и лед твоих ладоней, и запахи твоих волос.

И злая память сердце гложет, расстаться легче чем забыть

Духи с названием Быть-Может, не зря забыты, Может быть.

И вдруг ты гордости прикажешь, осенним вечером глухим.

Откроешь дверь и тихо скажешь.... Я здесь оставила духи....!

Воспоминания похожи, на очень грустные стихи

В забытой сумочке из кожи, пылятся...Польские...духи!.

|

|

Без заголовка |

Chapter Ten.

The Shell and the Glasses

Chapter Eleven.

Castle Rock

|

|

[о путешествиях] |

Конечно, лучше всего пишется ночью.

Тут на досуге решила посидеть, помечтать о том, куда можно было бы отправиться.

Подумала о теплых странах. Подумала о Европе. Подумала об Америке.

И к несчастью (а может и к счастью) обнаружила, что хочу побывать везде и везде успеть.

Потом начала придумывать, где возьму деньги, кого возьму с собой, что положу в чемодан.

В общем, что я хотела сказать-то... мечтайте, господа!

Мечтать - это круто!

У мечты есть такая особенность - сбываться. ;)

|

|

[Навеяло] |

Почти на строчки,

Ловлю поштучно и в развес,

Леплю комочки.

Мир побелел до немоты,

Почти до звона,

И в этом белом мире ты -

Моя икона.

Январь - раздача покрывал,

Набитых пухом,

Тем, кто так долго замерзал,

И падал духом.

Тем, кто так долго был в пути,

Идя по кругу,

И грел на собственной груди

Как птицу вьюгу...

Но вот искристый снегопад

Принёс надежду,

Пусть не ко дню и невпопад,

Не в масть, а между,

И я ловлю её в ладонь,

Леплю комочки,

И жжётся холод как огонь

В последней строчке.

Пускай вымарывает век

Мечты построчно,

Но за твоим окошком снег

Такой же точно...

© Copyright: Безымянная Тетрадь, 2012

|

|

Итоги |

сайты года: twitter

знакомство года: салютовские ребята и Чааааарли)

программа года: ППХ

фильмы года: Ёлки 2 =)

блюдо года: пицца)

напиток года: какао

язык года: английский)

мечта года: автомобиль

несбывшаяся мечта года: автомобиль)

город года: Рига

место года: ДОЛ Салют

открытие года: я знаю английский!)

персональное событие года: я умею работать с детьми

исполнитель года: Coldplay

песня года: Give me a sign

лучшая поездка года: в Салют.. или в Латвию.. еще не решила)

разочарование года: Макс

вещь года: iPod

человечище года: Баааах, Клю, Юля

коллега\однокурсник года: Бах

пожелание года: не парься)

препод года: Сосновская бляяя))

вопрос года: "и чё?"

время суток года: ночь

книги года: Константин Аврилов "Ангел"

одежда года: джинсы

покупка года: iPod, кухня, окна

фраза года: чиииииик

безумие года: 4ая смена

|

|

[Believe] |

Сижу и смотрю фильм "Мост в Терабитию", пью чай и почему-то очень хочу Новый год

Я почему-то еще верю, что желание, загаданное в тот Новый год исполнится, а если нет - то загадаю его в этот Новый год и тогда уж оно точно исполнится.

А еще я верю, что у Катюшки все будет хорошо и она еще родит мне кучу племянников.

Верю, что случайности неслучайны.

Верю, что сказки - не вымысел, что чудеса и правда случаются, нужно только верить.

Верила, верю и буду верить.

|

|

[ноябрь 2011] |

Да о чем тут говорить, даже мой magic 8 ball без понятия, чего я хочу...

|

|

привет, мам |

У мамы сейчас много забот и всяких важных дел помимо меня. Почти каждый вечер уезжает к бабушке, оттуда на работу, с работы опять к бабушке. Она стала меньше за мной следить. В этом, конечно, есть свои плюсы. И минусы.

Она не знает - завтракаю я или нет. Что я одела в универ, что обула. Готова я к семинару или нет. До которого времени я гуляю, сижу за компом. Могу за ним просидеть до утра и перед ним же заснуть. Какая у меня температура.

Да, она поможет, если я попрошу. Да, она может со мной и поболтать, если она дома, что бывает крайне редко. Да, мне стало свободнее.

Но я в своей жизни еще никому так не была нужна, как моей маме. А сейчас я чувствую себя.. ненужной что ли.

Хорошо, что она знает, как я ее люблю.

|

|

The End |

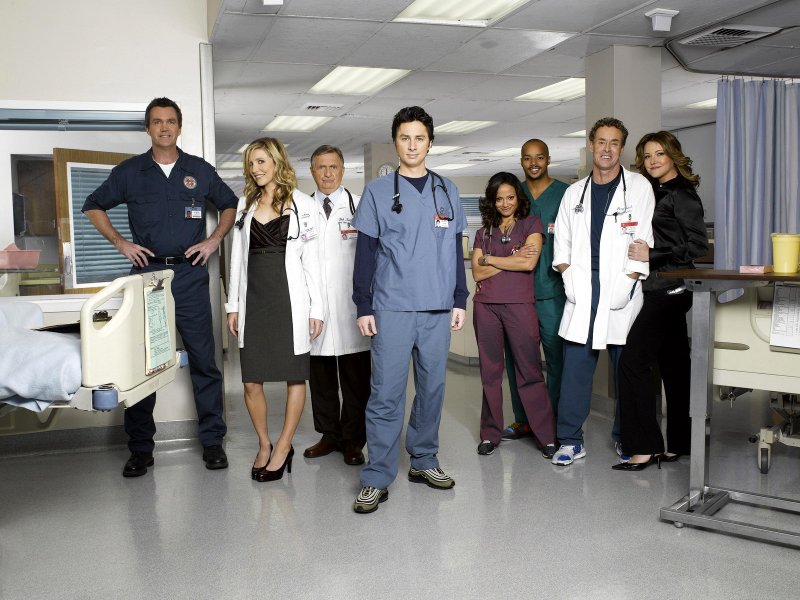

Все когда-то заканчивается. Теперь могу с уверенностью сказать, что сериал "Scrubs" - один из самых любимых.

Это не просто комедия, каждая серия наполнена смыслом. Всю последнюю серию сидела с платком в руках, такая трогательная серия. Конечно, я смогу и буду пересматривать любимые серии, но такого чувства, как сейчас уже не будет. После последней серии, когда показывали, как снимали серию и моменты, которые не вошли в серию, показали самый-самый последний эпизод Зака Браффа (JD). Когда режиссер произнес "Зак Брафф закончил съемки", все начали обниматься, смеяться, плакать и благодарить друг друга. Похоже, что они сроднились. И я с ними =) "I'm no Superman"... Спасибо, ребята, вы всегда поднимаете мне настроение, вы клёвые)

Да, я сентиментальная)

|

|

0сень |

Осень либо ставит все на свои места, либо запутывает еще больше.

|

|

День 30 - Ваши взлеты и падения в этом месяце. |

У меня все монотонно, неинтересно. Без взлетов и падений. Comme il faut.

|

|

День 29 - Цели на ближайшие 30 дней. |

сдать все экзамены и зачет по физ-ре

закрыть сессию

подготовиться к лагерю

все собрать, купить и отправиться в лагерь 1 июня

|

|

День 28 - То, что вы не пропустите. |

Премьеру фильма Пираты Карибского моря 4 - На странных берегах.

А еще я не хочу пропустить лагерь в Латвии летом.

|

|

День 27 - Проблемы, которые у вас были. |

Не думаю, что у меня были какие-то проблемы. Может какие-то временные трудности, но их нельзя назвать проблемами.

|

|