-ћузыка

- ћузыка

- —лушали: 41 омментарии: 5

-ћетки

-я - фотограф

Ѕородатые ирисы

-ѕоиск по дневнику

-ѕодписка по e-mail

-—татистика

ќбразы сотанистов |

Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1828-82.

ƒанте √абриэль –оссетти.

јвтопортрет 1847г.

Self portrait (1847)

–оссетти происходил из семьи италь€нских эмигрантов, его отец √абриэль, сын кузнеца и необразованной дочери сапожника, получил образование в университете Ќеапол€ и зан€л должность либретиста в оперной компании. ѕосле освобождени€ »талии от наполеоновского вторжени€ молодой поэт включилс€ в политическую де€тельность на стороне национального освободительного движени€, получившего название –исорджементо. ≈му пришлось бежать от политических преследований сначала на ћальту, а затем в јнглию. «десь √абриэль –оссетти сначала преподавал италь€нский €зык дет€м состо€тельных семей, а позднее стал профессором италь€нского €зыка в оролевском колледже в Ћондоне. ¬ семье –оссетти существоваал культ поэзии, и все его дети так или иначе были св€заны с поэтическим творчеством и литературной де€тельностью. ≈го дочь ристина стала поэтом, младший сын ”иль€м стал художественным критиком и биографом семьи, старший сын ƒанте √абриэль в юности про€вл€л большой интерес к поэзии, прежде всегго к ƒанте, переводами которого занималс€ его отец, и к английской поэзии - Ўелли, итсу, Ѕроунингу, Ѕлейку.

ѕрофессорский пост √абриэл€ –оссетти позвол€л его дет€м бесплатно обучатьс€ в королевском колледже, ƒанте училс€ п€ть лет, посещал уроки рисовани€, изучал латынь, греческий, французский и немецкий. ќкончив колледж в 1841 году, он поступает в художественную школу, азванную по имени художника √енри —асса јкадемией —асса. ‘актически это были подготовительные курсы к поступлению в оролевскую академию. ¬ основном в школе копировали античные модели и изучали анатомию. ƒанте не любил копировать, пропускал уроки и рисовал карикатуры на античные статуи, однако школу в 1845 году окончил и поступил в школу оролевской академии. јкадемию прин€то ругать за рутину и имитацию классики. ƒанте занимаетс€ рисунком, создаЄт многочисленные портреты сестры, брата, отца, матери.

ƒанте √абриэль –оссетти ѕортрет ристины –оссетти 1847 г.

ƒанте √абриэль –оссетти ѕортрет ”иль€ма –оссетти 1853 г.

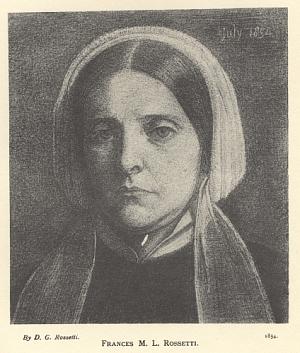

Frances M.L. Rossetti.

ќн много читает и пишет стихи и прозу. ¬ академии им написаны поэмы "Ѕлесед дамозел" и "—он моей сестры". ¬ 1847 году –оссетти открывает дл€ себ€ творчество Ѕлейка.

¬ 1847 году –оссетти знакомитс€ с ‘ордом ћэдоксом Ѕрауном.Ќа семь лет старше –оссетти он был уже зрелым художником, училс€ в антверпенской јкадемии, побывал во ‘ранции и »талии. –оссетти посещал его мастерскую и работал, или скорее училс€ там. Ѕраун рассказал будущим прерафаэлитам о искусстве назарейцев, с которым он познакомилс€ в –име.

Ќа академической ежегодной выставке 1847 года среди 1474 экспонатов –оссетти восхитила картина ’анта " анун св. јгнессы", художники начинают работать вместе. ’ант знакомит –оссетти с ƒжоном Ёвериттом ћиллэ, третим основателем прерафаэлитского братства.

ѕервые работы –оссетти: иллюстраци€ к поэме "¬орон" Ё.ѕо 1847 г и "—п€ща€" 1849 ещЄ далеки от профессилнализма.

¬ 1849 году –оссетти пишет первую картину маслом "ƒевичество Ѕогоматери"

–оссетти и ’ант посетили Ѕельгию и ‘ранцию, открыли дл€ себ€ искусство ¬ан Ёйка и ћемлинга, оказавшее большое вли€ние на развитие искусства –оссетти, особенно его аквалери иллюстрации к ƒанте. –оссетти отличало разннобразие интересов, он писал стихи, переводил "Ќовую жизнь" ƒанте, издавал журнал "√ерм", писал, рисовал, занималс€ дизайном и витражами.

√лавным источником тем дл€ –оссетти была литература и не только ƒанте, двойником которого он себ€ ощущал, но и ћэлори с его јртуровским циклом "“ристан выпивает любовный напиток", Ўекспир "√амлет и ќфели€" , Ѕибли€ "ћари€ ћагдалина" антична€ мифологи€ и многие другие. ¬ работах –оссетти вырисовываетс€ его главна€ тема - любовь и победа любви над смертью.

ƒанте √абриэль –оссетти јвтопортрет 1855 г.

ћузей ‘итцвиль€ма, јнгли€

Fitzwilliam Museum - Cambridge, UK

јвтопортрет 1870

Self portrait (1870)

ѕќЋЌџ… —ѕ»—ќ –јЅќ“ –ќ——≈““» The full list of Ross

1. –ќ——≈““» 1847-51 Rossetti 1847-51

2.–ќ——≈““» 1852-1854 ROSSETTI 1852-54

4.–оссетти 1856-57 Rossetti 1856-57

5.Rossetti 1858-59 –оссетти 1858-59

“ворчество –оссетти легко разбиваетс€ на определЄнные периоды, тематические, временные и т.п. аждый из них св€зан с определЄнной моделью. ¬ этой св€зи € и буду рассматривать р€д конкретных творений художника, по возможности придержива€сь хронологического пор€дка. ќ каждой из моделей отдельна€ подробна€ рубрика.

ћодели –оссетти.

∆енщины прерафаэлитов обычно попадают в две категории: модели (по преимуществу жЄны, любовницы, или в случае ристины –оссетти - сЄстры художников) или женщины художники прерафаэлиты. ƒжейн моррис попадает в первую, а —иддал можно отнести к обеим категори€м.

The Pre-Raphaelite women generally fall into two categories: artist’s models (who were predominately wives, lovers, or in the case of Christina Rossetti, sisters of the artists) or Pre-Raphaelite women artists (Lizzie Siddal can be included in both categories). Jane Morris falls in the first category.

1. ристина –оссетти. Christina Rossetti. ристина –оссетти

2.Ёлизабет —иддал. Elizabeth Siddal. Ёлизабет —иддал

3. јлекса ¬айлдинг. Alexa Wilding. јЋ≈ —ј ¬ј…Ћƒ»Ќ√ ALEXA WILDING

4. ‘ани орнфорт. Fanny Cornforth ‘анни орнфорт

5. јнни ћиллер. Annie Miller. јЌЌ» ћ»ЋЋ≈– ANNIE MILLER

6.ƒжейн ћоррис ЅЄрден Jane Morris Burden ƒ∆≈…Ќ ћќ––»— Ѕ®–ƒ≈Ќ JANE MORRIS BURDEN

7. ћари —партали —тилман. Marie Spartali Stillman.

8. Ёдвард –оберт ’ьюз Edward Robert Hughes Ёдвард –оберт ’ьюз

—сылка на видео муз –оссетти:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KW6ATsQTpcw&feature=related

1849* встречает Ёлизабет —иддал и использует еЄ, как основную модель (не позвол€€ позировать другим).

1856* встречает ‘ани орнфорт и использует еЄ, как основную модель.

1857* встречает ƒжейн ћоррис.

1860* женитс€ на —иддал.

1862* —иддал умирает.

1863* ‘ани орнфорт становитс€ домоправительницей у кого-то другого.

1865* использует ƒжейн ћоррис, как основную модель

1849• met Elizabeth Siddal and used her as the main model (not to be used by the others)

1858• met Fanny Cornforth and used her as the main model

1857• met Jane Morris

1860• married Siddal

1862• Siddal died

1863• Fanny Cornforth became somebody else's housekeeper.

1865• used J. Morris as the main model

—тиль –оссетти легко узнаваем, возможно, € кощунствую, но на его полотнах все модели приобретают один и тот же облик и трудно различимы, о пристрастии к рыжим волосам € ещЄ напишу, возможно, унификации способствовала привычка художника приставл€ть причЄску одной модели к лицу другой и приверженность определЄнному типу фигуры а также стремление к идеализации модели (не такие уж они красавицы на фото). ¬ своих наблюдени€х € не одинок. ристина –оссетти так описывает свои впечатлени€ в стихотворении «¬ студии художника»:

«ќдно лицо гл€дит со всех картин,

ќдна фигура на полотнах бродит или полулежит,

—крываетс€ за ширмой, из зеркала си€ет красотой.

“о королева в платье, как рубин,

“о безым€нна€ девица в платьице зелЄном,

—в€та€, ангел, всЄ она не больше и не меньше.

Ќа живописца с полотна она гл€дит наивно,

ј он еЄ лицо глазами жадными ласкает день и ночь.

расива, как луна и весела как свет дневной,

Ќе затуманен облик горем, ожиданьем долгим.

Ќет, это не портрет, но плод его мечты.

ѕеревод мой, пардон.

«¬ студии художника» из «ƒо сих пор неопубликованного» под редакцией ћайкла –оссетти 1896.

‘One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-green,

A saint, an angel – every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.’

Cristina Rossetti.

‘In an Artist’s Studio’ 1856. from New Poems by Cristina Rossetti Hitherto Unpublished or Uncollected, edited by Michael Rossetti, 1896.

ѕервые официальные выставки живописи, подписанной ѕ.–.Ѕ. (значение не было раскрыто публике) имели место в Ћондоне в 1849 году. –оссетти выставил ƒетство ƒевы ћарии на —вободной ¬ыставке в √айд ѕарке, она также демонстрировалась в оролевской јкадемии вместе с »забеллой ћилле и –иензи ’анта. ƒетство ƒевы мари было первой крупномасштабной картиной –оссетти. ќсновыва€сь на средневековой живописи он употребил сложную иконографию.

The first official shows of painting inscribed P.R.B. – whose meaning had not been revealed to the public – took place in London in 1849. Rossetti exhibited The Girlhood of Mary Virgin at Free Exhibition at Hyde Park Corner, also showing it at the Royal Academy with Millais’ Isabella and Hunt’s Rienzi.

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin was Rossetti’s first large-scale painting. Drawing on medieval religious painting, he deployed a complex iconography.

–»—“»Ќј –ќ——≈““» Ѕ–ј“— јя ЋёЅќ¬№ » –≈Ћ»√»ќ«Ќјя Ё «јЋ№“ј÷»я.

ƒетство ƒевы ћарии. 1848-1849.

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. 1849.

83,2*65,4 см

ак вс€кий бедный, начинающий художник, –оссетти использовал в качестве моделей дл€ своих первых полотен родственников: мать, сестру, брата. ƒл€ этого первого полотна большого масштаба (ƒетство ƒевы ћарии) модел€ми послужили его сестра и мать. —ложную иконографию полотна он изложил в двух сонетах; на раме полотна и в каталоге.

Ёто символы: ¬ центре красной скатерти ћать и ƒева вышивают

ветку лилии с двум€ цветками, она почти совершенна, но не хватает ещЄ одного цветка, это символ того, что »исус ещЄ не рождЄн. ¬ышивают с натуры, перед ними стоит ангелочек, а вазе перед ним ветка лилии с трем€ цветками.

—имволы флоры: лили€ – символ чистоты, пальма и тЄрн предвещают семь радостей и семь горестей ƒевы. √олубь - дух св€той, на подоконнике лампа ? то собирает виноград тоже не €сно.

“есна€ ассоциаци€ между поэтическим текстом и изображением отражает амбиции –оссетти быть как художником, так и поэтом.

Models were his mother and sister. Its Rossetti’s first large-scale painting. The complex iconography he explained in a sonnet inscribed on the frame and in another one in the catalog;

‘These are symbols. On that close of red

I’ the centre, is the Tri-point – perfect each

Except the second of its points, to teach

That Christ is not yet born.’

Floral symbols: the lily is the symbol of purity, the palm and the thorn prefigure the seven joys and sorrows of the Virgin.

THE GIRLHOOD OF MARY VIRGIN "ќ“–ќ„≈—“¬ќ ћј–»»"

(For a Picture) ( картине)

This is that blessed Mary, pre-elect ¬от та первоизбранница ћари€

God's Virgin. Gone is a great while since she ѕренепорочна€. ѕрошла пора,

Dwelt thus in Nazareth of Galilee. огда она смиренна и добра,

Her kin she cherished with dwvout respect, «десь, в √алилее, дни вела благие:

Her gifts were simpleness of intellect, ¬ уме глубоком - помыслы простые;

And supreme patience. From her mother's knee ротка, в долготерпении мудра,

Faithful and hopeful; wise in charity; Ќеколебима в вере и щедра

Strong in grave peace; in duty circumspect. ≈й долг предуказал пути пр€мые.

So held she through her girlhood; as it were “акой она в девичестве св€том,

An angel-watered lily, that near God ¬злеле€нна€ ангелом лиле€,

Grows and is quiet. Till one dawn, at home –астЄт, склонив пред √осподом чело,

She woke in her white bed, and had no fear Ќо день придЄт - и с утренним лучом

At all, - yet wept till sunshine, and felt awed: ќна проснЄтс€, оробеть не сме€,

Because the fulness of the time was come. ¬ слезах - зане речЄнное пришло.

1848.

‘урор против ѕрерафаэлитов подн€лс€, когда –оссетти выставил Ecce Ancilla Domini! ¬ Ќациональном »нституте в апреле 1850. ≈го брат кратко изложил подход к передаче религиозной темы, описав картину, как «средство изложени€ идей». артина была задумана как часть диптиха, втора€ панель которого должна была изображать смерть ƒевы ћарии, но никогда не была исполнена. ритика нашла картину раздражающей, так как она показалась им слишком новаторской и вызывающей.

Ћюбопытна иконографи€ картины – ƒева показана полулежащей. »спользование нетрадиционной палитры, фактически сведЄнной к основным цветам (доминирует белый цвет, хот€ ƒева традиционно ассоциируетс€ с голубым цветом) вызвало бешенство критики. ќбща€ атмосфера картины нереальна, но почти мучительное выражение, которое –оссетти придал ƒеве очень человечно. артина была новаторским изображением Ѕлаговещень€. ќдин из критиков характеризовал –оссетти как «верховного жреца этой ретроградной школы».

The furore against the Pre-Raphaelites began when Rossetti showed Ecce Ancilla Domini! At the National Institution in April 1850. His brother summarized his approach to the representation of religious themes by describing this painting as a ‘vehicle for representing ideas’. It was intended as part of diptych, the second panel of which would have shown the Virgin’s death, though it was never executed. The critics found this painting disturbing because it was too innovative and daring.

The iconography is curious, with the Virgin shown semi-prostrate. The use of a most untraditional palette virtually reduced to primary colors (white is dominant, whereas the Virgin is normally associated with blue) unleashed the fury of the critics. The atmosphere is unreal but the almost anguished expression Rossetti gives to the Virgin is very human. The painting was an innovative rendering of the theme of the Annunciation. One critic describe the painter as ‘the high priest of this retrograde school’

Ѕлаговещенье

Ecce Ancilla Domini! 1849 - 1850. The Tate Gallery - London.

72,6*41,9 см.

ак и детсво ƒевы ћарии, эта картина во многом вдохновлена средневековой живописью, которую –оссетти видел во ‘ландрии и »талии. ћоделью ƒевы послужила ристина.

Like The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, it is strongly inspired by the medieval pictures Rossetti had seen in Flanders and Italy. Christina was his model.

National Portrait Gallery - London, UK

Christina and Frances Rossetti (1877)

ристина –оссетти - ќ –»—“»Ќ≈ –ќ——≈““»

‘јЌЌ» ќ–Ќ‘ќ–“ ѕЋќ“№ » ¬ќ∆ƒ≈Ћ≈Ќ»≈.

Ќј…ƒ≈ЌЌјя. 1854-81.

FOUND. 91,4*80cm

Delaware Art Museum - Delaware, USA

"Ќайденна€" единственна€ картина на современную тему, исполненна€ –оссетти. ћоделью послужила ‘анни орфорт, проститутка (какое совпадение с темой картины!) и экономка художника. Ќа картинах –оссетти ‘анни предстаЄт рыжеволосой девушкой "в теле", в контрасте с эфирным изображением других моделей - ƒжейн ћоррис и Ёлизабет —иддал.

Found the only contemporary theme treated by that painter. The model was Fanny Cornforth, a prostitute and his mistress.

In Rossetti's paintings, Fanny Cornforth appears as a fleshy redhead, in contrast to his more ethereal treatments of his other models, Jane Morris and Elizabeth Siddal.

»меетс€ множество возможных источников и параллелей к «Ќайденной» –оссетти (1854-81), так как проституци€ в то врем€ была предметом оживлЄнных общественных и литературных дебатов. „арльз ƒиккенс, включивший проститутку в свой роман «ƒэвид опперфильд» основал приют дл€ раска€вшихс€ проституток. »нтересна€ ассоциаци€ приходит на ум в этой св€зи. Ќебезызвестно, что первым произведением, приобретЄнным “реть€ковым дл€ своей галереи была картина «»скушение», на тему соблазнени€ девушки, попавшей в трудное финансовое положение. “реть€ков также основал фонд поддержки бесприданниц.

¬икторианска€ совесть, особенно в своих литературных и живописных про€влени€х, посто€нно фокусировалась на женской слабости во всех еЄ формах (прелюбоде€ние, незаконнорожденные, проституци€). ¬икторианцы живо интересовались и в общем сочувственно подходили к проблеме, счита€, что ситуаци€ €вилась результатом развити€ индустриального общества и урбанизации, что привело к утрате обществом невинности сельской жизни – рассматриваемой как суща€ јркади€ – и подвергло женщин всевозможным искушени€м.

«√уртовщик покинул свою телегу…и пробежал небольшое рассто€ние за прошедшей мимо девушкой…и она, узнав его, упала на колени». (письмо ’анту 1855) –оссетти помещает сцену в довольно убогую часть Ћондона, Blackfriars Bridge – ћост „Єрных ћонахов. артина, возможно, была вдохновлена книгой √енри ћайхью «Ћондон труда и Ћондон бедн€ков» (1851-1862). Ётот √енри пр€мо таки ƒжек Ћондон какой-то.

ак всегда у прерафаэлитов картина наполнена символикой различного толка, бросаютс€ в глаза мост на заднем плане – символ перехода к грешной жизни и телЄнок в сети на телеге, то есть невинна€ овечка, пойманна€ в сети зла.

ќна вскричала, сердце ожесточив: «ќставь мен€, теб€ не знаю €! ѕрочь убирайс€!» (перевод мой). Ёто строки из незаконченной поэмы –оссетти «Ќайденна€», вдохновлЄнной его же одноимЄнной картиной.

–оссетти, который страстно интересовалс€ поэзией »таль€нского –енессанса и особенно ƒанте, начал писать в 1840-е, в самом начале своей карьеры художника, хот€ первый сборник стихов был опубликован только в 1870-м. ѕерерыв во времени объ€сн€етс€ тем, что рукописи стихов –оссетти положил в гроб преждевременно умершей в 1862 жены Ёлизабет —иддал и они были эксгумированы только семь лет спуст€. ¬от такие италь€нские страсти. (курсив мой).

‘She cries in her locked heart, -“Leave me - I do not know you – go away!’

Rossetti from the poem ‘Found’, that was inspired by the painting of the same name, which was never completed.

Rossetti, who was passionately interested in the poetry of the Italian Renaissance and particularly the works of Dante, began writing at the very outset of his artistic career, in the late 1840s, though his first collection of Poems was not published until 1870. The reason of the lapse in time was because Rossetti had put the manuscripts of his poems in Elizabeth Siddal’s coffin on her premature death in 1862. They were only exhumed seven years later.

ƒама —в€того √рал€.

The Damsel of the Sanct Grael

92*57,7 см 1874г.

Lady Lilith (red chalk on paper).

62x57 cms

’от€ и значительно более противоречива€ модель, чем —иддал или ћоррис, ‘анни была не только предметом некоторых замечательных работ –оссетти, но и была преждевременно забыта. ќна послужила моделью дл€ Ћ»Ћ»“ - первой жены јдама в еврейской мифологии, рассматриваемой, как воплощение вожделени€.Sibylla Palmifera была задумана, как противоположность образа Ћилит, моделью послужила јлекса ¬айлдинг. ќна представл€ла " расоту ƒуши" - сонет, который –оссетти написал в сопровождение картины. —кромно одета€ —ибил сидит в храме, окружЄнна€ эмблемами Ћюбви - упидон, —мерти - череп и “айны - сфинкс. ¬ противоположность этому Ћилит восхищаетс€ собой в зеркале. ѕервоначально контраст между картинами был очень заметен, но в 1872-3 году –оссетти переписал голову ‘аннии-Ћилит, заменив еЄ по требованию покупател€ на јлексу ¬айлдинг и оригинальна€ концепци€ была разрушена. “аким образом дл€ Ћилит модел€ми послужили и ‘анни и јлекса.

Can you imagine the Virgin, or Christina Rossetti, like this?

ј вот и ещЄ порци€ ню, эскиз к —в€той ≈лизавете венгерской. 1852. (ћог же, когда хотел).

ј вот и ещЄ порци€ ню, эскиз к —в€той ≈лизавете венгерской. 1852. (ћог же, когда хотел).

—ивилла ѕальмифера.

Sibylla Palmifera

Ёта величественна€ картина демонстрирует св€зь между поэзией и живописью, характерную дл€ –оссетти. ќдин из сонетов из "ƒома жизни" толкует образ —ивиллы (или расоты ƒуши).

Ќа картине множество символических деталей: —ивилла держит пальмовую ветвь, что означает ѕобеду и —лаву, некоторые источники утверждают, что –оссетти стремилс€ выразить победу души над смертью. ¬ самом деле, другие символы кажетс€ поддерживают такую интерпретацию. Ѕабочки, порхащие на заднем фоне - это символы воскресшей души, а маки, изображЄнные в вернем правом углу, часто используютс€ как символы сна или смерти. ѕозади —ивиллы јмур с пов€зкой на глазах, а под ним неугасимый светильник любви. — другой стороны изображЄн череп-символ смерти и сфинкс - сивол загадки. —ивилла ѕальмифера это также пример главной одержимости –оссетти - изображение прекрасной женщины, идеального образа преследующего его воображение. ћоделью художника на этой картине была јлекса ¬айлдинг, одна из "потр€сающих воображение" моделей прерафаэлитов. ќна позировала и дл€ других картин –оссетти (например, Ћилит) и других прерафаэлитов, например —идони€ фон Ѕорк Ѕерн- ƒжонса.

The magnificent painting Sibylla Palmifera demonstrates the connections artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti often made between his paintings and his poetry. One of the sonnets from the House of Life reveals the subject of Sibylla Palmifera (or "Soul's Beauty"): This is that Lady Beauty, in whose praiseThy voice and hand shake still, - long known to theeBy flying hair and fluttering hem, - the beatFollowing her daily of thy heart and feet,How passionately and irretrievably,In what fond flight, how many ways and days! The painting features a great deal of symbolic detail. The woman holds a palm, which suggests victory - some sources state that Rossetti meant to represent the victory of the soul over death. Indeed, other symbols in the work seem to reinforce this interpretation. The butterflies that hover in the background are symbols of the soul, and the poppies that appear in the upper right corner are often used to symbolize sleep or death in art. Sibylla Palmifera is also an example of one of Rossetti's primary artistic obsessions - depicting the beautiful woman that so haunted his imagination. In this image, the artist's model was the 'stunner' Alexa Wilding. In addition to Sibylla Palmifera, the lovely Alexa Wilding appears in several of Rossetti's other works, including his Lady Lilith, La Sidonia von Bork" by Edward Burne-Jones, 1860 (Tate Gallery London).

Bocca Baciata

Bocca Baciata

Year1859

Oil on canvas 33,7*30,5 см.

Location Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston

Ёта картина –оссетти представл€ет поворотный пункт в его карьере. ¬первые он изображает одну женскую фигуру и создаЄт стиль, который впоследствии стал "подписью" его работ. ћоделью послужила ‘анни орнфорт, главна€ вдохновительница чувственных женских образов у –оссетти.

Ќазвание, буквально означающее "уже целованные губы" намеккает на сексуальную опытность предмета и вз€то из италь€нской пословицы, которую жудожник записал на обратной стороне холста:"Bocca baciata non perde ventura, anzi rinnova come fa la luna." "√убы, которые целовали, не тер€ют своей свежести, они обновл€ютс€ как луна".

–оссетти, изысканный перводчик италь€нской поэзии, веро€тно прочитал поговорку в ƒекамероне Ѕокаччо, где она использована, как кульминаци€ новеллы об Alatiel, прекрасной сарацинской принцессе, котораф€ несмотр€ на секс дес€ток тыс€ч раз с восемью различными любовниками в течение четырЄх лет успешно представл€ет себ€ королю как невеста-девственница.

–оссети объ€сн€ет в письме William Bell Scott, что он пыталс€ писать плоть более плотно, выпукло и избежать "того, что € знаю, €вл€етс€ моей посто€нной ошибкой, довольно распостранЄнной в живописи прерафаэлитов - "пунктирное" изображение тела... ƒаже у хороших старых мастеров портреты и простые сюжеты почти всегда шедевры по цвету и исполнению, € думаю, то помн€ об этом, можно наконец научитс€ живописи". ¬озможно, на картину оказал вли€ние портрет сводной сестры ћилле —офи √рей, который ћилле написал двум€ годами ранее.

Sophie Gray.

Bocca Baciata (1859) is a painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti which represents a turning point in his career. It was the first of his pictures of single female figures, and established the style that was later to become a signature of his work. The model was Fanny Cornforth, the principal inspiration for Rossetti's sensuous figures.

The title, meaning "mouth that has been kissed", refers to the sexual experience of the subject and is taken from the Italian proverb written on the back of the painting:

Bocca baciata non perde ventura, anzi rinnova come fa la luna.

‘The mouth that has been kissed does not lose its savour,

indeed it renews itself just as the moon does.’

Rossetti, an accomplished translator of early Italian literature, probably knew the proverb from Boccaccio’s Decameron where it is used as the culmination of the tale of Alatiel: a beautiful Saracen princess who, despite having had sex on perhaps ten thousand occasions with eight separate lovers in the space of four years, successfully presents herself to the King of the Algarve as his virgin bride.

Rossetti explained in a letter to William Bell Scott that he was attempting to paint flesh more fully, and to "avoid what I know to be a besetting fault of mine - & indeed rather common to PR painting - that of stipple in the flesh...Even among the old good painters, their portraits and simpler pictures are almost always their masterpieces for colour and execution; and I fancy if one kept this in view, one might have a better chance of learning to paint at last."

The painting may have been influenced by Millais' portrait of his sister-in-law Sophie Gray, completed two years earlier.

–ќ——≈““» и ЁЋ»«јЅ≈“ —»ƒƒјЋ, любовь в стиле ¬озрождени€.

First Anniversary 1853

42*61 cm

Ёлизабет —иддал Ёлизабет —иддал.

ќна впервые по€вл€етс€ на акварели «ѕерва€ годовщина смерти ¬еатриче» и становитс€ любимой моделью, товарищем по искусству и возлюбленной –оссетти.

Ћюбовь к Ёлизабет —иддал (модели ћилле дл€ ќфелии) оказала большое вли€ние на жизнь и карьеру –оссетти. »нтересно, что, как

правило, –оссетти получал своих возлюбленных из вторых рук; —иддал от ћилле, ƒжейн ћоррис от ћорриса, јнни ћиллер от ’анта, то есть говор€ проще имел завидущие глаза и загребущие руки, не говор€ уж о том, что у господина «большое сердце». »таль€нец, что с него возьмЄшь. ƒом на „атам ѕлэйс, в который они переехали в 1852 году стал декорацией к их страстным любовным отношени€м, он был одержим —иддал, как моделью и она стала ему товарищем и коллегой в художественном творчестве. — самого начала –оссетти направл€л и побуждал еЄ рисовать и писать стихи. ’от€ поэтические работы молодой женщины не были широко известны, еЄ графика скоро завоевала значительную репутацию. — 1855 по 57 год ƒжон –ускин выплачивал ей пособие в обмен на все еЄ работы. ќни очень напоминали работы –оссетти и отражали их завораживающие и клаустрофобические любовные отношени€.

—ам –оссетти спроецировал свою страсть к —иддал в живописи, иллюстрирующей историю любви ƒанте и ¬еатриче, например Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1855) and Dantis Amor (1859-60). Ёто панно первоначально представл€ло собой центральную из трЄх дверок в верхней части большого лар€, бывшего частью мебели ћорриса на ѕлощади расного Ћьва и затем в расном ƒоме.

–оссетти разрывалс€ между идеальной любовью к —иддал и своими св€з€ми с орнфорт, проституткой из —охо и јнни ћиллер, любовницей ’анта. ќн в конце концов женилс€ на —иддал в 1860 году.

Rossetti fell in love with Elizabeth Siddal (the model Millais used for Ophelia) and their intense relationship profoundly affected his life and career. The hose in Chatham Place to which tey moved in 1852 was the backdrop to their complex and passionate love affair, in which Elizabeth Siddal became his obsessional model and his artistic double. From the start of their relationship, Rossetti guided and encouraged her to draw and to compose poetry. Although the young woman’s poems were not wildly known, her graphic work soon gained a considerable reputation. From 1855 to 1857 John Ruskin gave her a kind of allowance in exchange for all her works. They showed a strong resemblance to Rossetti’s, reflecting a claustrophobic and fascinating love affair.

Rossetti himself projected his passionate feelings for her into paintings illustrating the story of Dante and Beatrice, such as Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1855) and Dantis Amor (1859-60); this panel was originally the centre door out of three on the upper section of a large settle that was part of Morris’ furniture at Red Lion Square and then at the Red House. Rossetti was torn between his idealized love for Elizabeth Siddal and his liaisons with some of his other models: Fanny Cornforth, a Soho prostitute, and Annie Miller, who was also Hunt’s mistress. He eventually married Siddal in 1860.

Beginning in 1853, with his watercolor, The First Anniversary of the Death of Beatrice, Rossetti painted her in many works. In this piece, Lizzie portrays a regal woman, who visits the distinguished Dante as he writes his autobiography. Too absorbed with his overwhelming passion for Beatrice, Dante initially fails to notice the other people present in the room. Wearing a long, tailored blue gown and a teal headdress, Lizzie clearly occupies a position of considerable rank and beauty. Following this work, Rossetti used Lizzie in other Dante-related pieces, including Dante's Vision of Rachel and Leah (1855) and Beatrice Meeting Dante at a Marriage Feast, Denies him her Salutation (1851).

In the latter painting, Lizzie represented Dante's obsession, Beatrice, and again wore a distinguished, long green dress and possessed exquisite beauty. Surrounded by throngs of supporters, she confronts Dante with a defiance that attests to her authority.

Ѕлаженна€ Ѕеатриче

–оссетти начал картину через год после смерти —иддал.

Beata Beatrix

86,4*66 cm

Dante Gabriel Rossetti began "Beata Beatrix" a year after Siddal's death.

рушение семейной жизни отрицательно сказалось на творчестве –оссетти, только спуст€ годы вернулс€ он к жанру женского портрета. Ѕеату Ѕеатрикс он писал много лет, с 1864 по 1870 год. Ёто было воспоминание о жене. ќснованна€ на сюжете смерти Ѕеатриче из "Ќовой жизни" ƒанте, она стала одной из известнейших произведений символизма. ¬ жЄлтой дымке Ћиззи - Ѕеатриче сидит в позе умирающей с закрытыми глазами и подн€тым подбородком, кажетс€,она остро сознаЄт приближающуюс€ смерть, птица - вестник смерти вкладывает цветок мака (символ смерти) в еЄ руку. ћак, как символ, весьма двусмысленен, если вспомнить, что —иддал умерла (покончила с собой?) как раз от передозировки опи€. Ќа заднем планет фигуры ƒанте и Ћюбви, в центе мост ¬еккио во ‘лоренции. ритики приветствовали картину за еЄ эмоциональное воздействие, которое передаЄтс€ даже просто через колорит и композицию. —мысл истинной истории любви –оссетти и его жены ещЄ углубл€етс€, Ћиззи всЄ ещЄ оказывала сильное вли€ние на его творчество.

Rossetti again represented Lizzie as Dante's Beatrice in one of his most famous works, Beata Beatrix, (1864-1870) which he painted as a memorial to Lizzie after her death. This piece also mimicked the death of Dante's love in his autobiographical work, Vita Nuova. In the work, amidst a yellow haze of relatively indistinct shapes, including Florence's Ponte Vecchio and the figures of Dante and Love, Lizzie sits, representing Dante's Beatrice. With an upturned chin and closed eyes, Lizzie appears keenly aware of her impending fate, death. A bird, which serves as the messenger of death, places a poppy in her hands. Critics have praised the piece for its emotional resonance, which can be felt simply through the work's moving coloring and composition. The true history of Rossetti and his beloved wife further deepens its meaning; although their love had waned at that point, Lizzie still exerted a powerful influence on the artist.

Beata Beatrix 1877

Oil on canvas.

Width: 682 mm

Height: 864 mm

ќдна из нескольких версий данной темы. Ёта картина осталась незаконченной к моменту смерти –оссетти и фон был завершон ‘орд ћэдокс Ѕрауном. ¬ этой версии маки красные, возможно. как €вный намЄк на опиум. ≈щЄ одна верси€ картины в коллекции “ейт. »меютс€ многочисленные наброски карандашом к этой картине в музее Ѕирмингема.

One of several versions of this subject, this painting was unfinished at the time of Rossetti's death and the background was completed by Ford Madox Brown. In this version, the poppies are red, perhaps an explicit reference to opium-derived laudanum. Another version of the painting is in the Tate collection. There are also numerous related pencil studies in the Birmingham collection, as well as a large ornamental maijolica dish painted with a scene of Rossetti's 'Dante's Dream'.

The dove symbolise a messenger of death. Usually the dove represents Peace or the Holy Spirit. Here, it is the messenger of death. In other versions of the painting the dove is red, symbolising passion and death.

The poppy symbolise Death. This is an opium poppy sometimes used to make the drug laudanum. Rossetti's wife died from a drug overdose.

The sundial represent the passing of time. The shadow on the sundial falls on 9 o'clock. This is time of Beatrice's death in the poem.

Why is Beatrice's tunic green and the dress purple? Green for life, purple for sorrow. Green means spring life and hope. Purple means sorrow and death.

ƒјЋ≈≈ ќ –ќ——≈““»:next page следующа€ страница.

| омментировать | « ѕред. запись — дневнику — —лед. запись » | —траницы: [1] [Ќовые] |