Добавить любой RSS - источник (включая журнал LiveJournal) в свою ленту друзей вы можете на странице синдикации.

Исходная информация - http://planet.mozilla.org/.

Данный дневник сформирован из открытого RSS-источника по адресу http://planet.mozilla.org/rss20.xml, и дополняется в соответствии с дополнением данного источника. Он может не соответствовать содержимому оригинальной страницы. Трансляция создана автоматически по запросу читателей этой RSS ленты.

По всем вопросам о работе данного сервиса обращаться со страницы контактной информации.

[Обновить трансляцию]

Mozilla Reps Community: Reps Weekly Call – June 11th 2015 |

Last Thursday we had our weekly call about the Reps program, where we talk about what’s going on in the program and what Reps have been doing during the last week.

Summary

- Featured Events.

- EU Code Week / Africa Code Week.

- Bangladesh Community Meetup.

- What’s going on at community forums.

AirMozilla video

Detailed notes

Shoutouts to @emma_irwin, @ThePhoenixBird and @gautha91, who have just left their one year Council term, Bangladesh community for creating all the plans to support the launch of the Webmaker app in Bangladesh and @mkohler for all his awesome work and help in bugzilla.

Featured events

These are some of the events that took place last week.

- DevTalk Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania. 11th

- FSA Leaders Camp, Mataasnakahoy, Philippines. 12th, 13th

- Webmaker meetup Bucaramanga, Bucaramanga, Colombia. 12th-14th.

- Mombassa Webmaker Party, Coast, Kenya. 13th.

Don’t forget to add your event to Discourse, and share some photos, so it can be shared on Reps Twitter account

EU Code Week / Africa Code Week

We were invited to either organize an event during the EU Code week and Africa Code week or join an event that has been organized by other people. To add your event to our Coding Map of Europe please visit the events page. You can use #codeEU Toolkit for organizers and a list of resources to help get started.

If you need help or have a question you can get in touch with EU Code Week Ambassadors in your country.

Bangladesh Community meetup

Core members of the Bangladesh community got together for the first time and worked on planning the launch of Webmaker in Bangladesh: very ambitious goal: 10000 downloads!

They also started thinking about the projects that will come after Webmaker: a push for Fennec (Firefox for Android). Most smartphone users in Bangladesh are on Android so there’s a great opportunity for Mozilla there.

What’s going on at community forums?

There are some interesting conversations that are currently going on at the community forums you might want to check out:

- Channel for mozillians to suggest new feature changes

- Building the Mozilla we want: Response to the recent anonymous emails

- New Council onboarded

- Reps and Firefox Tiles

Also as a reminder, the Participation team has its own public category where the team communicates their daily work.

Don’t forget to comment about this call on Discourse and we hope to see you next week!

https://blog.mozilla.org/mozillareps/2015/06/12/reps-weekly-call-june-11th-2015/

|

|

Mozilla Release Management Team: Firefox 39 beta3 to beta4 |

Beta 4 contains a small number of patches (beta 5 will have more). A beta release mostly focused on graphic issues.

- 19 changesets

- 38 files changed

- 657 insertions

- 301 deletions

| Extension | Occurrences |

| js | 16 |

| cpp | 8 |

| h | 4 |

| jsm | 3 |

| ini | 3 |

| css | 2 |

| xml | 1 |

| html | 1 |

| Module | Occurrences |

| browser | 13 |

| toolkit | 10 |

| gfx | 5 |

| media | 4 |

| testing | 2 |

| mobile | 1 |

| js | 1 |

| embedding | 1 |

| dom | 1 |

List of changesets:

| Edwin Flores | Bug 1160445 - Add detailed logging for EME promise failures. r=cpearce, r=bholley, a=lizzard - 263f9318751a |

| Chris Pearce | Bug 1160101 - Revert browser.eme.ui.enabled pref change from Bug 1160101. r/a=backout - 51f5d060b146 |

| Terrence Cole | Bug 1170665 - Disable the windows segfault popup in the shell. r=jandem, a=NPOTB - f5030585d5c0 |

| Mike Connor | Bug 1171730 - Funnelcake builds should use geo-specific defaults. r=florian, a=sledru - e25fcbbd93a4 |

| James Graham | Bug 1171916 - Disable another unstable navigation-timing test on osx. a=test-only - b009c272abac |

| Erik Vold | Bug 1142734 - Use Timer.jsm and add some logs to jetpack-addon-harness.js. r=mossop, a=test-only - b2455e4eca11 |

| Gijs Kruitbosch | Bug 1166066 - Fix opening new windows from a private window. r=jdm, a=lizzard - a7f385942c76 |

| Matt Woodrow | Bug 1153123 - Don't upload in the ImageBridge thread if A8 texture sharing is broken. r=Bas, a=lizzard - d744ad902c75 |

| David Major | Bug 1167189 - Use a size annotation on the OOM abort. r=bholley, a=lizzard - 561e0bdf9614 |

| David Anderson | Bug 1170211 - Fix a startup crash when attempting to test D3D11 texture sharing. r=jmuizelaar, a=lizzard - ec9c793f24ad |

| Mark Hammond | Bug 1170079 - Don't treat an old readinglist last-sync-date as a prolonged error if it's disabled. r=adw, a=lizzard - 9dd33c2b4304 |

| Richard Newman | Bug 1170819 - Enable payments in Fennec release channel. r=mfinkle, r=AndyM, a=lizzard - a2c9c4c49319 |

| Gijs Kruitbosch | Bug 1172270 - backed out changeset b38b8126e4d1 (Bug 1160775), a=backout/relman - 62f75a6439dd |

| Richard Marti | Bug 1169981 - Add win10 media query to listitem and treechildren. r=dao, a=lizzard - 0c1d5e2461d4 |

| Marco Bonardo | Bug 1167915 - "Add a Keyword for this Search" does not work anymore on POST forms. r=ttaubert, a=lizzard - d810a18a0e0f |

| Mark Hammond | Bug 1170926 - Have the hamburger menu notice the 'needs reauthentication' state. r=adw, a=lizzard - 7cee52e60929 |

| Jeff Muizelaar | Bug 1171094 - Disallow D3D11 ANGLE with old DisplayLink drivers. r=Bas, a=lizzard - da14f82d9caf |

| Randell Jesup | Bug 1132318 - Merge SelectSendFrameRate with SelectSendResolution. r=bwc, a=abillings - 48c9f45a00f2 |

| Matt Woodrow | Bug 1170143 - Disable texture sharing if we've blacklisted direct2d. r=Bas, a=lizzard - 4241def0561b |

http://release.mozilla.org/statistics/39/2015/06/12/fx-39-b3-to-b4.html

|

|

Karl Dubost: Just Patch This! (or 101 for patching Firefox) |

Contributing to Mozilla projects can be done in many ways. This week, a Webcompat bug about behavior differences in between browsers led me to propose a patch on Firefox and get it accepted. I learned a couple of things along the way. That might be useful for others.

The Webcompat Bug - Search Placeholder On Mobile Sites

It started with a difference of behavior in between Chrome and Firefox on Android devices for Nikkei Web site reported by kudodo from Mozilla Japan. I looked at the bug and checked the differences in Firefox 40 (Gecko 40) and Opera 30 (Blink/Chrome 43).

Indeed the placeholder text appears in Gecko and not in Blink.

span> id="searchBlank" action="" method="get">

span> id="searchBox" placeholder="

|

|

John O'Duinn: The canary in the coal mine |

After my recent “We are ALL Remoties” presentation at Wikimedia, I had some really great followup conversations with Arthur Richards at WikiMedia Foundation. Arthur has been paying a lot of attention to scrum and agile methodologies – both in the wider industry and also specifically in the context of his work at Wikimedia Foundation, which has people in different locations. As you can imagine, we had some great fun conversations – about remoties, about creating culture change, and about all-things-scrum – especially the rituals and mechanics of doing daily standups with a distributed team.

Next time you see a group of people standing together looking at a wall, and moving postit notes around, ask yourself: “how do remote people stay involved and contribute?” Taking photographs of the wall of postit notes, or putting the remote person on a computer-with-camera-on-wheeled-cart feels like a duct-tape workaround; a

MacGyver fix done quickly, with the best of intentions, genuinely wanting to help the remote person be involved, but still not-a-great experience for remoties.

There has to be a better way.

We both strongly agree that having people in different locations is just a way to uncover the internal communication problems you didn’t know you already have… the remote person is the canary in the coal mine. Having a “we are all remoties” mindset helps everyone become more organized in their communications, which helps remote people *and* also the people sitting near each other in the office.

Arthur talked about this idea in his recent (and lively and very well attended!) presentation at the Annual Scrum Alliance “Global Scrum Gathering” event in Phoenix, Arizona. His slides are now visible here and here.

Arthur talked about this idea in his recent (and lively and very well attended!) presentation at the Annual Scrum Alliance “Global Scrum Gathering” event in Phoenix, Arizona. His slides are now visible here and here.

If you work in an agile / scrum style environment, especially with a geo-distributed team of humans, it’s well worth your time to read Arthur’s presentation! Thought provoking stuff, and nice slides too!

http://oduinn.com/blog/2015/06/11/the-canary-in-the-coal-mine/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Brown Bag Talk: Passwords and Login Problems |

How can Mozilla improve the user experience around logins and passwords? Over the past six weeks, the Passwords team, joined by Amelia Abreu, has spent...

How can Mozilla improve the user experience around logins and passwords? Over the past six weeks, the Passwords team, joined by Amelia Abreu, has spent...

https://air.mozilla.org/brown-bag-talk-passwords-and-login-problems/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Participation at Mozilla |

The Participation Forum

The Participation Forum

|

|

Air Mozilla: Assembl'ee G'en'erale de l'ADULLACT |

3 Conf'erences sur le logiciel libre suivies de l'AG de l'ADULLACT (rapports, pr'esentation des comptes, approbation des comptes, budget pr'evisionnel, renouvellement de mandats, questions/r'eponses).

3 Conf'erences sur le logiciel libre suivies de l'AG de l'ADULLACT (rapports, pr'esentation des comptes, approbation des comptes, budget pr'evisionnel, renouvellement de mandats, questions/r'eponses).

|

|

Air Mozilla: Mozilla Hosts NewCo Silicon Valley with VP Platform Engineering David Bryant |

NewCo is a festival for innovation where innovative companies invite the community to their spaces to hear directly about the impact they are making.

NewCo is a festival for innovation where innovative companies invite the community to their spaces to hear directly about the impact they are making.

|

|

Air Mozilla: Quality Team (QA) Public Meeting |

This is the meeting where all the Mozilla quality teams meet, swap ideas, exchange notes on what is upcoming, and strategize around community building and...

This is the meeting where all the Mozilla quality teams meet, swap ideas, exchange notes on what is upcoming, and strategize around community building and...

https://air.mozilla.org/quality-team-qa-public-meeting-20150610/

|

|

Air Mozilla: Tech Talk: Shipping Firefox |

Lawrence Mandel will be speaking on shipping Firefox or how to push code from thousands of developers to hundreds of millions of users.

Lawrence Mandel will be speaking on shipping Firefox or how to push code from thousands of developers to hundreds of millions of users.

|

|

Air Mozilla: Product Coordination Meeting |

Duration: 10 minutes This is a weekly status meeting, every Wednesday, that helps coordinate the shipping of our products (across 4 release channels) in order...

Duration: 10 minutes This is a weekly status meeting, every Wednesday, that helps coordinate the shipping of our products (across 4 release channels) in order...

https://air.mozilla.org/product-coordination-meeting-20150610/

|

|

Air Mozilla: The Joy of Coding (mconley livehacks on Firefox) - Episode 18 |

Watch mconley livehack on Firefox Desktop bugs!

Watch mconley livehack on Firefox Desktop bugs!

https://air.mozilla.org/the-joy-of-coding-mconley-livehacks-on-firefox-episode-18/

|

|

Mozilla WebDev Community: Extravaganza – June 2015 |

Once a month, web developers from across Mozilla get together to plot which C-level executive we’re going to take out next. Meanwhile, we find time to talk about the work that we’ve shipped, share the libraries we’re working on, meet new folks, and talk about whatever else is on our minds. It’s the Webdev Extravaganza! The meeting is open to the public; you should stop by!

You can check out the wiki page that we use to organize the meeting, or view a recording of the meeting in Air Mozilla. Or just read on for a summary!

Shipping Celebration

The shipping celebration is for anything we finished and deployed in the past month, whether it be a brand new site, an upgrade to an existing one, or even a release of a library.

Lazy-loading Fonts on MDN

First up was shobson with news about lazy-loading CSS fonts on MDN. The improvement allows users to see content immediately and avoids text flashing associated with displaying the fonts after they’ve loaded. The pull request is available for review for anyone interested in how it was achieved.

Lazy-loading Tabzilla on Air Mozilla

Next was peterbe, who told us about how Air Mozilla is now lazy-loading Tabzilla, the white Mozilla tab at the top of many of our websites. By not loading the extra code for the tab until the rest of the page has loaded, they were able to reduce the load time of the initial document by 0.7 seconds. Check out the bug for more info.

ContributeBot

pmac stopped by to show off ContributeBot, an Hubot script that reads contribute.json files and welcomes new visitors when the channel is quiet with information from the file. It gives new users info about where to find documentation, as well as pinging important people in the project to let them know that there’s someone new.

Open-source Citizenship

Here we talk about libraries we’re maintaining and what, if anything, we need help with for them.

pyelasticsearch 1.3

ErikRose wanted to let people know that pyelasticsearch 1.3 is out. It now has HTTPS support as well as new constructor arguments that help reduce the number of times you repeat yourself while using the library.

New Hires / Interns / Volunteers / Contributors

Here we introduce any newcomers to the Webdev group, including new employees, interns, volunteers, or any other form of contributor.

| Name | Role | Work |

|---|---|---|

| Gloria Dwomoh | Outreachy Intern | Air Mozilla |

| Michael Nolan | Intern | Air Mozilla |

| Peter Elmers | Intern | DXR |

This was a… productive month.

If you’re interested in web development at Mozilla, or want to attend next month’s Extravaganza, subscribe to the dev-webdev@lists.mozilla.org mailing list to be notified of the next meeting, and maybe send a message introducing yourself. We’d love to meet you!

See you next month!

https://blog.mozilla.org/webdev/2015/06/10/extravaganza-june-2015/

|

|

Mozilla Addons Blog: Add-ons Update – Week of 2015/06/10 |

I post these updates every 3 weeks to inform add-on developers about the status of the review queues, add-on compatibility, and other happenings in the add-ons world.

The Review Queues

- Most nominations for full review are taking less than 10 weeks to review.

- 233 nominations in the queue awaiting review.

- Most updates are being reviewed within 7 weeks.

- 101 updates in the queue awaiting review.

- Most preliminary reviews are being reviewed within 10 weeks.

- 268 preliminary review submissions in the queue awaiting review.

If you’re an add-on developer and would like to see add-ons reviewed faster, please consider joining us. Add-on reviewers get invited to Mozilla events and earn cool gear with their work. Visit our wiki page for more information.

Firefox 39 Compatibility

The Firefox 39 compatibility blog post is up. The automatic compatibility validation will be run probably later this week.

Firefox 40 Compatibility

The Firefox 40 compatibility blog post is also coming up.

As always, we recommend that you test your add-ons on Beta and Firefox Developer Edition (formerly known as Aurora) to make sure that they continue to work correctly. End users can install the Add-on Compatibility Reporter to identify and report any add-ons that aren’t working anymore.

Extension Signing

We announced that we will require extensions to be signed in order for them to continue to work in release and beta versions of Firefox.

Yesterday I posted this update of where we are with signing on AMO. In a nutshell, all AMO extensions for Firefox that passed review have been signed, and all new versions will be signed once they pass review. We have enabled Unlisted extension submission, but it’s currently under testing, so expect some bugs. The major issues will be resolved in the coming week and we’ll make an announcement on this blog to indicate we’re ready for your submissions.

The wiki page on Extension Signing has information about its timeline, as well as responses to some frequently asked questions.

Electrolysis

Electrolysis, also known as e10s, is the next major compatibility change coming to Firefox. In a nutshell, Firefox will run on multiple processes now, running content code in a different process than browser code. This should improve responsiveness and overall stability, but it also means many add-ons will need to be updated to support this.

We will be talking more about these changes in this blog in the future. For now we recommend you start looking at the available documentation.

https://blog.mozilla.org/addons/2015/06/10/add-ons-update-66/

|

|

Adrian Gaudebert: Rethinking Socorro's Web App |

Credits @lxt

I have been thinking a lot about what we could do better with Socorro's webapp in the last months (and even more, the first discussions I had about this with phrawzty date from Spring last year). Recently, in a meeting with Lonnen (my manager), I said "this is what I would do if I were to rebuild Socorro's webapp from scratch today". In this post I want to write down what I said and elaborate it, in the hope that it will serve as a starting point for upcoming discussions with my colleagues.

State of the Art

First, let's take a look at the current state of the webapp. According to our analytics, there are 5 parts of the app that are heavily consulted, and a bunch of other less used pages. The core features of Socorro's front-end are:

- The home page graph

- Top Crashers

- Super Search

- The signature report page (currently report/list/)

- Individual crash report pages

Those we know people are looking at a lot. Then there are other pages, like Crashes per User, Top Changers, Explosive Crashes, GC Crashes and so on that are used from "a lot less" to "almost never". And finally there's the public API, on which we don't have much analytics, but which we know is being used for many different things (for example: Spectateur, crash-stats-api-magic, Are we shutting down yet?, Such Comments).

The next important thing to take into account is that our users oftentimes ask us for some specific dataset or report. Those are useful at a point in time for a few people, but will soon become useless to anyone. We used to try and build such reports into the webapp (and I suppose the ones from above that are not used anymore fall into that category), but that costs us time to build and time to maintain. And that also means that the report will have to be built by someone from the Socorro team who has time for it, it will go through review and testing, and by the time it hits our production site it might not be so useful anymore. We have all been working on trying to reduce that "time to production", which resulted in the public API and Super Search. And I'm quite sure we can do even better.

Building Reports

Every report is, at its core, a query of one or several API endpoints, some logic applied to the data from the API, and a view generated from that data. Some reports require very specific data, asking for dedicated API endpoints, but most of them could be done using either Super Search alone or some combination of it with other API endpoints. So maybe we could facilitate the creation of such reports?

Let us put aside the authentication and ACL features, the API, the admin panel, and a few very specific features of the web app, to focus on the user-facing features. Those can be simply considered as a collection of reports: they all call one or several models, have a controller that does some logic, and then are displayed via a Django template. I think what we want to give our users is a way to easily build their own reports. I would like them to be able to answer their needs as fast as possible, without depending on the Socorro team.

The basic brick of a fresh web app would thus be a report builder. It would be split in 3 parts:

- the model controls the data that should be fetched from the API;

- the controller gets that data and performs logic on it, transforming it to fit the needs of the user;

- and the view will take the transformed data and turn it into something pretty, like a table or a graph.

Each report could be saved, bookmarked, shared with others, forked, modified, and so on. Spectateur is a prototype of such a report builder.

We developers of Socorro would use that report system to build the core features of the app (top crashers, home page graphs, etc. ), maybe with some privileges. And then users will be able to build reports for their own use or to share with teammates. We know that users have different needs depending on what they are working on (someone working on FirefoxOS will not look at the same reports than someone working on Thunderbird), so this would be one step towards allowing them to customize their Socorro.

One Dashboard to Rule Them All

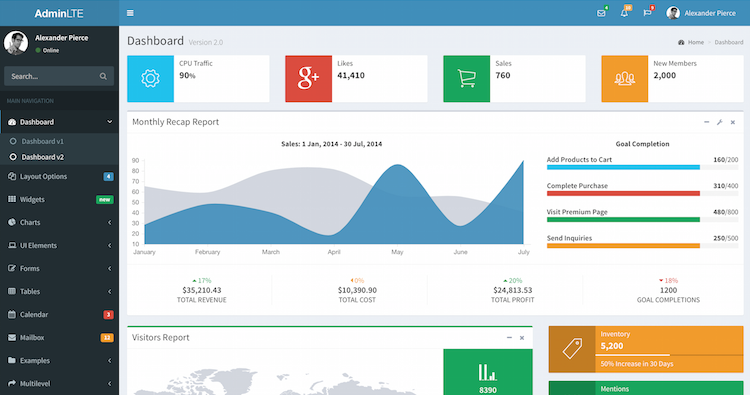

So users can build their own reports. Now what if we pushed customization even further? Each report has a view part, and that's what would be of interest to people most of the time. Maybe we could make it easy for a user to quickly see the main reports that are of interest to them? My second proposal would be to build a dashboard system, which would show the views of various reports on a single page.

A dashboard is a collection of reports. It is possible to remove or add new reports to a dashboard, and to move them around. A user can also create several dashboards: for example, one for Firefox Nightly, one for Thunderbird, one for an ongoing investigation... Dashboards only show the view part of a report, with links to inspect it further or modify it.

An example of what a dashboard could look like.

Socorro As A Platform

The overall idea of this new Socorro is to make it a platform where people can find what they want very quickly, personalize their tool, and build whatever feature they need that does not exist yet. I would like it to be a better tool for our users, to help them be even more efficient crash killers.

I can see several advantages to such a platform:

- time to create new reports is shorter;

- people can collaborate on reports;

- users can tweak existing reports to better fit their needs;

- people can customize the entire app to be focused on what they want;

- when you give data to people, they build things that you did not even dream about. I expect that will happen on Socorro, and people will come up with incredibly useful reports.

I Need Feedback

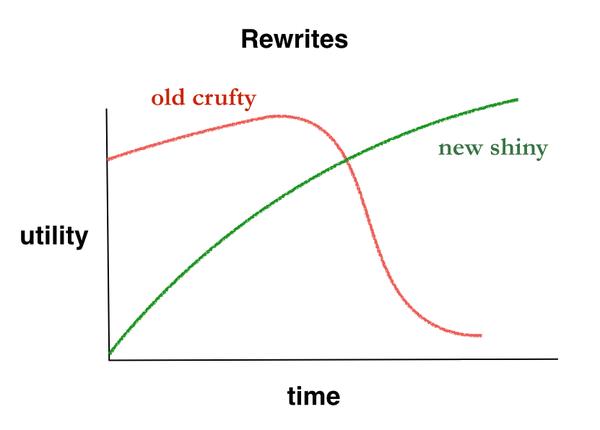

Concretely, the plan would be to build a brand new app along the existing one. The goal won't be to replace it right away, but instead to build the tools that would then be used to replace what we currently have. We would keep both web apps side by side for a time, continuing to fix bugs in the Django app, but investing all development time in the new app. And we would slowly push users towards the new one, probably by removing features from the Django app once the equivalent is ready.

I would love to discuss this with anyone interested. The upcoming all-hands meeting in Whistler is probably going to be the perfect occasion to have a beer and share opinions, but other options would be fine (email, IRC... ). Let me know what you think!

http://adrian.gaudebert.fr/blog/post/2015/06/10/rethinking-socorro-s-web-app

|

|

Morgan Phillips: service "Dockerized Firefox Builds" status |

"Behold child, 'tis buildbot"

In moving [Linux] jobs from buildbot to TaskCluster, I've worked on docker containers which will build Firefox with all of the special options that RelEng needs. This is really cool because it means developers can download our images and work within them as well, thus creating parity between our CI infrastructure and their local environments (making it easier to debug certain bugs). So, what's my status update?

The good news: the container for Linux64 jobs is in tree, and working for both Desktop and Android builds!

The better news: these new jobs are already working in the Try tree! They're hidden in treeherder, but you can reveal them with the little checkbox in the upper right hand corner of the screen. You can also just use this link: https://treeherder.mozilla.org/#/jobs?repo=try&exclusion_profile=false

# note: These are running alongside the old buildbot jobs for now, and hidden. The container is still changing a few times a week (sometimes breaking jobs), so the training wheels will stay on like this for a little while.

The best news: You can run the same job that the try server runs, in the same environment simply by installing docker and running the bash script below.

Bonus: A sister 32 bit container will be coming along shortly.

#!/bin/bash -e

# WARNING: this is experimental mileage may vary!

# Fetch docker image

docker pull mrrrgn/desktop-build:16

# Find a unique container name

export NAME='task-CCJHSxbxSouwLZE_mZBddA-container';

# Run docker command

docker run -ti \

--name $NAME \

-e TOOLTOOL_CACHE='/home/worker/tooltool-cache' \

-e RELENGAPI_TOKEN='ce-n-est-pas-necessaire' \

-e MH_BUILD_POOL='taskcluster' \

-e MOZHARNESS_SCRIPT='mozharness/scripts/fx_desktop_build.py' \

-e MOZHARNESS_CONFIG='builds/releng_base_linux_64_builds.py' \

-e NEED_XVFB='true' \

mrrrgn/desktop-build:16 \

/bin/bash -c /home/worker/bin/build.sh \

;

# Delete docker container

docker rm -v $NAME;|

|

Mike Hommey: PSA: mach now stores its log automatically |

It’s been a frustration for a long time: oftentimes, you need to dig the log of the build or test run you just did, but didn’t redirect it. When you have enough backlog in your terminal, that can work itself out, but usually, what happens is that you rerun the command, redirecting it to a log file, hoping what you’re looking for will happen again.

For people working on the build system, it’s even worse because it involves someone else: someone comes and say “my build fails with $message”, and usually, thanks to parallel builds, the actual error message is buried deep in their terminal history… when they have a terminal history (Windows console, I’m looking at you).

Anyways, as of bug 985857, as long as you don’t already redirect mach‘s output to a file, it will now save it for you automatically.

At the moment, the feature is basic, and will store the last log of the last command (mostly). So if you run mach build followed by mach xpcshell-test, only the log for the latter will be available, and the log of the former will be lost.

The log is stored in the same format as mach uses when you give it the -l argument, which is an aggregate of many json pieces, and not very user friendly. Which is why mach now also has a new command to read those logs:

mach show-log

By default, it will display the last log mach stored, but you can also give it the path to any log you got out of mach with the -l argument.

So you can do either:

machmach show-log

or

mach -l log-file.jsonmach show-log log-file.json

Note that show-log will spawn less automatically, so that you have paging and search abilities.

|

|

First off, the single most important note about React I ever wrote.

Let me start this blog post with the most important thing about React, so that we understand why things happen the way they do:

If used correctly, your users will think they are manipulating a UI, when in fact they are manipulating React, which may then update the UI

Sounds simple, doesn't it? But it has a profound effect on how UI interactions work, and how you should be thinking about data flow in React applications. For instance, let's say we have a properly written React application that consists of a page with some text, and a slider for changing the text's opacity. I move the slider. What happens?

In traditional HTML, I move the slider, a change event is triggered, and if I had an eventListener hooked up for that, I could then do things based on that change.

React doesn't work like that

Another short and sweet sentence: React doesn't work with "changes to the UI" as you make them; React doesn't allow changes to the UI without its consent. Instead, React intercepts changes to the UI so they don't happen, then triggers the components that are tied to the UI the user thinks they're interacting with, so that those components can decide whether or not a UI update is necessary.

In a well written React application, this happens:

- I try to move the slider.

- The event is intercepted by React and killed off.

- As far as the browser knows, nothing has happened to that slider.

- React then takes the information about my UI interaction, and sends it to the component that owns the slider I tried to manipulate.

- If that component accepts my attempt at changing the UI, it will update its state such that it now renders in a way that makes it look identical to the traditional HTML case:

- As far as I'm concerned, as a user, I just moved the slider. Except in reality I didn't, my UI interaction asked React to have that interaction processed and that processing caused a UI update.

This is so different from traditional HTML that you're going to forget that. And every time you do, things will feel weird, and bugs might even be born. So, just to hopefully at least address that a tiny bit, once more:

If used correctly, your users will think they are manipulating a UI, when in fact they are manipulating React, which may then update the UI

Now then, try to remember this forever (I know, simple request, right?) and let's move on.

Revisiting the core concepts of modeling "your stuff" with React

If you've been working with React for a while it's easy to forget where "your mental construct of a thing" ends and where your UI components begin, and that makes it hard to reason about when to use React's state, when to use props, when to use instance variables, and when to offload things entirely to imported functionality objects. So, a quick refresher on the various bits that we're going to be looking at, and how to make use of them:

Your thing

This is an abstract idea, and generally breaks up into lots of tiny things that all need to "do something" to combine into a larger whole that actual humans like to think in. "A blog post", "A page", or "a markdown editor" all fall into this category. When thinking about "your thing", it's tempting to call the specific instantiation of everything that this thing needs "its state", but I'm going to have to be curt and tell you to not do that. At least, let's be specific: whenever we talk about the thing's state, let's call it "the full state". That way we won't get confused later. If it doesn't have "full" in the description, it's not your thing's abstract meta all encompassing state.

React components

These are extremely concrete things, representing UI elements that your users will interact with. Components need not map one-to-one to those abstract ideas you have in your head. Think of components as things with three levels of data: properties, state, and "plain old javascript stuffs".

Component properties: "this.props"

These are "constructor" properties, and are dictated by whoever creates an instance of the component. However, React is pretty clever and can deal with some situations in ways you may not expect coming at React from a traditional HTML programming paradigm. Let's say we have the following React XML - also known as JSX (This isn't HTML or even XML, it's just a more convenient way to write out programming intent, and maps directly to a React.createElement call. You can write React code without ever using JSX, and JSX is always first transformed back to plain JS before React runs it. Which is why you can get JavaScript errors "in your XML", which makes no sense if you still think that stuff you wrote really is XML):

Parent = React.createClass({

render() {

return (

<...>

The child's position is always the same in this case, and when the Parent first renders, it will create this Child with some content. But this isn't what really happens. React actually adds a level of indirection between the code you wrote, and the stuff you see client-side (e.g. the browser, a native device, etc.): a VIRTUAL DOM has been created based on your JSX, and it is that VIRTUAL DOM that actually controls how things are changed client-side. Not your code. So the diffrence kicks in when we change the content that should be in that child and we rerender, to effect a new child:

- Something happens to Parent that changes the output of

getCurrentChildContent - Parent renders itself, which means the

- React updates the VIRTUAL element associated with the Parent, and one of the updates is for the VIRTUAL Child element, which has a new property value

- Rather than destroying the old Child and building a new one with the new property, React simply updates the VIRTUAL element so that it is indistinguishable from what things would have been had we destroyed and created anew.

- the VIRTUAL DOM, once marked as fully updated, then reflects itself onto client the so that users see an updated UI.

The idea is that React is supposed to do this so fast you can't tell. And the reason React is so popular is that it actually does. React is fast. Really fast.

Where in traditional HTML you might remove(old) and then append(new), React will always, ALWAYS, first try to apply a "difference patch", so that it doesn't need to waste time on expensive construction and garbage collection. That makes React super fast, but also means you need to think of your components as "I am supplying a structure, and that structure will get updated" instead of "I am writing HTML elements". You're not.

Component state: "this.state"

This is the state of the React component. A react component that represents a piece of interactive text, for instance, will have that text bound as its state, because that state can be changed by the component itself. Components do not control what's in their props (beyond the limited 'use these default values for props that were not passed along during construction'), but they do control their state, and every update to the state triggers a render() call.

This can have some interesting side effects, and requires some extra thinking: If you have a text element, and you type to change that text, that change needs to be reflected to the state before it will actually happen.

Remember that important sentence from the start of the post:

If used correctly, your users will think they are manipulating a UI, when in fact they are manipulating React, which may then update the UI

And then let's look at what happens:

- the user types a letter in what they think is a text input field of some sort

- the event gets sent to React, which kills it off immediately so the browser never deals with it, and then sends it on to the component belonging to the VIRTUAL element that backs the UI that the user interacted with

- the component handles the event by extracting the data and updating its state so that its text reflects the new text

- the component renders itself, which updates the VIRTUAL element that backs the UI that the user sees, replacing its old text (pre-user-input) with the next text (what-the-user-thinks-they-wrote). This change is then reflected to the UI.

- the user sees the updated content, and all of this happened so fast that they never even notice that all this happens behind the scenes. As far as they know, they simply typed a letter.

If we didn't use this state reflecting, instead this would happen:

- user types a letter

- React kills off the event to the VIRTUAL element

- there is no handler to accept the event, extract its value, and update the component state, so:

- nothing happens.

The user keeps hitting the keyboard, but no text shows up, because nothing changes in React, and so nothing changes in the UI. As such, state is extremely important to get right, and remembering how React works is of crucial importance.

Semantically refactored state: mixins

In additional to properties and state, React has a "mixin" concept, which allows you to write utility code that can tack into/onto any React class you're working with. For instance, let's look at an input component:

var Thing = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return { input: this.props.input || "" };

},

render: function() {

return

},

updateInput: function(evt) {

this.setState({ input: evt.target.value }, function() {

if (this.props.onUpdate) {

this.props.onUpdate(this.state.input);

}

});

}

});

Perfectly adequate, but if we have lots of components that all need to work with inputs, we can also do this:

var inputMixin = {

getInitialState: function() {

return {

input: this.props.input || ""

};

},

updateInput: function(evt) {

this.setState({ input: evt.target.value }, function() {

if (this.props.onUpdate) {

this.props.onUpdate(this.state.input);

}

});

}

};

var Thing = React.createClass({

mixins: [ inputMixin ],

render: function() {

return

},

});

We've delegated the notion of input state tracking and UI handling to a "plain JavaScript" object. But, one that hooks into React's lifecycle functions, so even though we define the state variable input in the mixin, the component will end up owning it and this.state.input anywhere in its code will resolve just fine.

Mixins allow you to, effectively, organise state and behaviour in a finer-grained way than just components allow. Multiple components that have nothing in common with respects to your abstract model can be very efficiently implemented by looking at which purely UI bits they share, and modeling those with single mixins. Less repetition, smaller components, better control.

Of course, it gets tricky if you refer to a state variable that a mixin introduces outside of that mixin, so that's a pitfall: ideally, mixins capture "everything" so that your components don't need to know they can do certain things, "they just work". As such, I like to rewrite the previous code to the following, for instance:

var inputMixin = {

getInitialState: function() {

return {

input: this.props.input || ""

};

},

updateInput: function(evt) {

this.setState({ input: evt.target.value }, function() {

if (this.props.onUpdate) {

this.props.onUpdate(this.state.input);

}

});

},

// JSX generator function, so components using this mixin don't need to

// know anything about the mixin "internals".

generateInputJSX: function() {

return

}

};

var Thing = React.createClass({

mixins: [ inputMixin ],

render: function() {

return (

...

{ this.generateInputJSX() }

...

);

},

});

Now the mixin controls all the things it needs to, and the component simply relies on the fact that if it's loaded a mixing somethingsometingMixin, it can render whatever that mixin introduces in terms of JSX with a call to the generateSomethingsomethingJSX function, which will do the right thing. If the state for this component needs to be saved, saving this.state will include everything that was relevant to the component and the mixin, and loading the state in from somewhere with a setState(stateFromSomewhere()) call will also do the right thing.

So now we can have two completely different components, such as a "Portfolio" component and a "User Signup" component, which have absolutely nothing to do with each other, except that they will both need the UI and functionality that the inputMixin can provide.

(Note that while it is tempting to use Mixins for everything, there is a very simple criterium for whether or not to model something using mixins: does it rely on hooking into React class/lifecycle functions like getInitialState, componentDidUpdate, componentWillUnmount, etc.? If not, don't use a mixin. If you just want to put common functions in a mixin, don't. Just use a library import, that's what they're for)

Instance variables and externals

These things are handy for supporting the component, but as far as React is concerned they "don't matter", because updates to them do nothing for the UI unless there is extra code for manually triggering a state change. And you can't trigger a state change on an instance variable, state changes happen through setState and property updates by parents.

That said, React components are just plain JavaScript, so there is nothing preventing you from using the same JS constructs that we use outside of React:

var library = require("libname");

var Thing = React.createClass({

mixins: [

require("somemixin"),

require("someothermixin")

],

getInitialState: function() {

this.elements = library.getStandardList();

return { elements: this.elements };

},

addElement: function(e) {

this.elements.push(e);

this.setState({ elements: this.elements });

},

render: function() {

return this.state.elements.map(...);

}

});

Perfect: in fact, using instance variables sometimes drastically increases legibility and ease of development, such as in this example. Calling addElement() several times in rapid succession, without this.elements, has the potential to lose state updates, effectively doing this:

var l1 = this.state.elements;+l1.push(e)+setState({ elements: l1 });var l2 = this.state.elements;+l2.push(e)+setState({ elements: l2 });var l3 = this.state.elements;+l3.push(e)+setState({ elements: l3 });

Now, if l3 is created before setState for l2 has finished, then l3 is going to be identical to l1, and after it's set, l2 could be drop over it, losing us data twice!

Instance variables to the rescue.

Static properties on the component class

Finally, components can also be defined with a set of static properties, meaning they exist "on the class", not on specific instances:

var Thing = React.createClass({

statics: [

mimetypes: require("mimetypes")

],

render() {

return I am a { this.props.type }!;

}

});

var OtherThing = React.createClass({

render: function() {

Of course like all good JS, statics can be any legal JS reference, not just primitives, so they can be objects or functions and things will work quite well.

Back to React: hooking up components

The actual point of this blog post, in addition to the opener sentence, was to look at how components can be hooked up, by choosing how to a) model state ownership, b) model component interactions, and c) data propagation from one component to another.

This is going to be lengthy (but hopefully worth it) so let's just do this the itemized list way and work our way through. We have two lists:

State ownership:

- centralized ownership

- delegated ownership

- fragmented ownership

- black box ownership

Component interactions:

- Parent to Child

- Parent to Descendant

- Child to Parent

- Child to Ancestor

- Sibling to Sibling

Data propagation:

- this.props chains

- targeted events using publish/subscribe

- blind events broadcasting

So I'm going to run through these, and then hopefully at the end tie things back together by looking at which of these things work best, and why I think that is the case (with which you are fully allowed to disagree and we should talk! Talking is super useful).

Deciding on State Ownership

Centralized ownership

The model that fits the traditional HTML programming model best is the centralized approach, where one thing "owns" all the data, and all changes go through it. In our editor app, we can model this as one master component, "Parent", with two child components, "Post" and "Editor", which take care of simply showing the post, and editing the post, respectively.

Out post will consist of:

var marked = require("marked");

var Post = React.createClass({

render: function() {

var innerHTML = {

dangerouslySetInnerHTML: {

__html: marked(this.props.content);

}

};

return ;

}

});

Our editor will consist of:

var tinyMCE = require("tinymce");

var Editor = React.createClass({

render: function() {

var innerHTML = {

dangerouslySetInnerHTML: {

__html: tinymce({

content: this.props.content,

updateHandler: this.onUpdate

});

}

};

return ;

},

onUpdate: function(evt) {

this.props.onUpdate(evt);

}

});

And our parent component will wrap these two as:

var Parent = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {

content: "",

editing: false

};

},

render: function() {

return (

);

},

// triggered when we click the post

switchToEditor: function() {

this.setState({

editing: true

});

},

// Called by the editor component

onUpdate: function(evt) {

this.setState({

content: evt.updatedContent,

editing: false

});

}

});

In this setup, the Parent is the lord and master, and any changes to the content must run through it. Saving and loading of the post to and from a data repository would, logically, happen in this Parent class. When a user clicks on the post, the "hidden" flag is toggled, which causes the Parent to render with the Editor loaded instead of the Post, and the user can modify the content to their heart's content. Upon completion, the Editor uses the API that the Parent passed down to ensure that its latest data gets reflected, and we return to the Post view.

The important question is "where do we put save and load", and in this case that choice is obvious: in Parent.

var staterecorder = {

componentWillMount: function() {

this.register(this, function loadState(state) {

this.setState(state);

});

},

register

componentWillUnmount: function() {

this.unregister(this);

},

}

var Parent = React.createClass({

mixins: [

require("staterecorder")

]

getInitialState: function() {

...

},

getDefaultProps: function() {

return { id: 1};

},

render: function() {

...

},

...

});

But: why would the Parent be in control? While this design mirrors our "abstract idea", this is certainly not the only way we can model things. And look closely: why would that Post not be the authoritative source for the actual post? After all, that's what we called it. Let's have a look at how we could model the idea of "a Post" by acknowledging that our UI should simply "show the right thing", not necessary map 1-on-1 to our abstract idea.

Delegated state management

In the delegated approach, each component controls what it controls. No more, no less, and this changes things a little. Let's look at our new component layout:

Out post is almost the same, except it now controls the content, and as such, this is now its state and it has an API function for updating the content if a user makes an edit (somehow) outside of the Post:

var marked = require("marked");

var database = require("database");

var Post = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

content: ""

},

componentWillMount: function() {

database.getPostFor({id : this.props.id}, function(result) {

this.setState({ content: result });

};

},

render: function() {

var innerHTML = {

dangerouslySetInnerHTML: {

__html: marked(this.props.content);

}

};

return ;

},

setContent: function(newContent) {

this.setState({

content: newContent

});

}

});

Our editor is still the same, and it will do pretty much what it did before:

var tinyMCE = require("tinymce");

var Editor = React.createClass({

render: function() {

var innerHTML = {

dangerouslySetInnerHTML: {

__html: tinymce({

content: this.props.content,

updateHandler: this.onUpdate

});

}

};

return ;

},

onUpdate: function(evt) {

this.props.onUpdate(evt);

}

});

And our parent, however, has rather changed. It no longer controls the content, it is simply a convenient construct that marries the authoritative component, with some id, to an editor when the user needs it:

var Parent = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {

editing: false

};

},

render: function() {

return (

);

},

// triggered when we click the post

switchToEditor: function() {

??????

this.setState({

editing: true

});

},

// Called by the editor component

onUpdate: function(evt) {

this.setState({

editing: false

}, function() {

this.refs.setContent(evt.newContent);

});

}

});

You may have spotted the question marks: how do we now make sure that when we click the post, we get its content loaded into the editor? There is no convenient "this.props" binding that we can exploit, so how do we make sure we don't duplicate things all over the place? For instance, the following would work, but it would also be a little ridiculous:

var Parent = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {

editing: false,

localContent: ""

};

},

render: function() {

return (

);

},

bindContent: function(newContent) {

this.setSTate({

localContent: newContrent

});

},

// triggered when we click the post

switchToEditor: function() {

this.setState({

editing: true

});

},

// Called by the editor component

onUpdate: function(evt) {

this.setState({

editing: false

}, function() {

this.refs.post.setContent(evt.newContent);

});

}

});

We've basically turned the Parent into a surrogate Post now, again with its own content state variables, even though the set out to eliminate that. This is not a path to success. We could try to circumvent this by linking the Post to the Editor directly in the function handlers:

var Parent = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {

editing: false

};

},

render: function() {

return (

);

},

// triggered when we click the post

switchToEditor: function() {

this.refs.editor.setContent(this.refs.post.getContent(), function() {

this.setState({

editing: true

});

});

},

// Called by the editor component

onUpdate: function(evt) {

this.setState({

editing: false

}, function() {

this.refs.post.setContent(evt.newContent);

});

}

});

This might seem better, but we've certainly not made the code easier to read by putting in all those async interruptions...

Fragmenting state across the UI

What if we took the genuinely distributed approach? What if we don't have "a Parent", with the Post and Editor being, structurally, sibling elements? This would certainly rule out the notion of duplicated state, but also introduces the issue of "how do we get data from the editor into the post":

var Post = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

content: ""

},

componentWillMount: function() {

database.getPostFor({id : this.props.id}, function(result) {

this.setState({ content: result });

};

somewhere.listenFor("editor:update", this.setContent);

},

render: function() {

var innerHTML = {

dangerouslySetInnerHTML: {

__html: marked(this.props.content);

},

onClick: this.onClick

};

return ;

},

onClick: function() {

// somehow get an editor, somewhere, to open...

somewhere.trigger("post:edit", { content: this.state.content });

},

setContent: function(newContent) {

this.setState({

content: newContent

});

}

});

The obvious thing to notice is that the post now needs to somehow be able to trigger "an editor", as well as listen for updates.

var Editor = React.createClass({

componentWillMount: function() {

somewhere.listenFor("post:edit", function(evt) {

this.contentString = evt.content;

});

},

render: function() {

var innerHTML = {

dangerouslySetInnerHTML: {

__html: tinymce({

content: this.contentString,

updateHandler: this.onUpdate

});

}

};

return ;

},

onUpdate: function(evt) {

somewhere.trigger("editor:update", evt);

}

});

Again, this seems less than ideal. While the Post and Editor are now nice models, we're spending an aweful lot of time in magical-async-event-land, and as designers, programmers, and contributors, we basically have no idea what's going on without code diving.

Remember, you're not just writing code for you, you're also writing code for people you haven't met yet. We want to make sure we can onboard them without going "here are the design documents and flowcharts, if you see anything you don't understand, please reach out and good luck". We want to go "here's the code. It's pretty immediately obvious how everything works, just hit F3 in your code editor to follow the function calls".

Delegating all state to an external black box

There is one last thing we can try: delegating all state synchronizing to some black box object that "knows how to state, yo". For instance, a database interfacing thing through which we perform lookups and save/load all state changes. Of all the options we have, this is the one that is absolutely the most distributed, but it also comes with some significant drawbacks.

var api = {

save: function(component, state) {

// update our data store, and once that succeeds, update the component

datastore.update(component, state).success(function() {

component.setState(state);

});

}

};

var Post = React.createClass({

...

componentWillMount: function() {

api.load(this, function(state) {

this.setState(state);

});

},

setContent: function(newContent) {

api.save(this, {

content: newContent

});

}

});

This seems pretty handy! we don't update our UI until we know the datastore has the up to date state, so are application is now super portable, and multiple people can, in theory, all work on the same data. That's awesome, free collaboration!

The downside is that this is a UI blocking approach, meaning that if for some reason the data store fails, components won't get updated despite there being no technical reason for that to happen, or worse, the data store can be very slow, leading to actions the user took earlier conflicting with their current actions because the updates happen while the user's already trying to make the UI do something else.

Of course, we can reverse the order of commits and UI updates, but that introduces an even harder problem: invalidating the UI if it turns out the changes cannot be committed. While the api approach has neat benefits, they rely on your infrastructure being reliable, and fast. If that cannot be guaranteed, then contacting a data store for committing states manually may be a better solution because it limits the store interactions to bootstrapping (i.e. loading previously modified components) and user-initiated synchronization (save buttons, etc).

Dealing with Component Relations

Parent to Child: construction properties

This is the classic example of using construction properties. Typically the parent should never tell the Child to do things via API calls or the like, but simply set up need property values, so that the Child can do "whatever it needs to do based on those".

Parent to Descendant: a modeling error

In React, this relationship is essentially void. Parents should only be concerned about what their children look like, and nothing else. If there are things hanging under those children, those things should be irrelevant to the Parent. If they're not, this is a sign that the choice of which components map to which abstract concepts was not thought out well enough (yet), and needs redoing.

Child to Parent: this.props

Children can trigger behaviour in their Parents as long as the Parent supplies the API to do so via construction properties. If a Parent has an API for "doing something based on a Child doing something", that API can be passed into along during Child construction in the same way that primitive properties are passed in. React's JSX is just 'JavaScript, with easier to read syntax' so the following:

render: function() {

return ;

}

is equivalent to:

render: function() {

return React.createElement("Child", {

content: this.state.content,

onUpdate: this.handleChildUpdate

});

}

And the child can call this.props.onUpdate locally whenever it needs the Parent to "do whatever it needs to do".

Child to Ancestor: a modeling error

Just like how Parents should not rely on descendants, only direct children, Children should never care about their Ancestors, only their Parents. If the Child needs to talk to its ancestor, this is a sign that the choice of which components map to which abstract concepts was, again, not thought out well enough (yet), and needs redoing.

Sibling to Sibling:

As "intuitive" as it might seem for siblings to talk to each other (after all, we do this in traditional HTML setting all the time), in React the notion of "siblings" is irrelevant. If a child relies on a sibling to do its own job, this is yet another sign that the choice of which components map to which abstract concepts was not thought out well enough (yet), and needs redoing.

Deciding on how to propagate data

Chains of this.props.fname() function calls

The most obvious way to effect communication is via construction properties (on the Parent side) and this.props (on the Child side). For simple Parent-Child relationships this is pretty much obvious, after all it's what makes React as a technology, but what if we have several levels of components? Let's look at a page with menu system:

Page -> menu -> submenu -> option

When the user clicks on the option, the page should do something. This feels like the option, or perhaps the submenu, should be able to tell the Page that something happened, but this isn't entirely true: the semantics of the user interaction changes at each level, and having a chain of this.props calls might feel "verbose", but accurately describes what should happen, and follows React methodology. So let's look at those things:

var Options = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return { this.props.label } ;

}

});

var Submenu = React.createClass({

render: function() {

var options = this.props.options.map(function(option) {

return

});

return { options }

;

},

select: function(label) {

this.props.

}

});

var Menu = React.createClass({

render: function() {

var submenus = this.props.menus.map(function(menu) {

return

{ this.formSections() }

);

},

navigate: function(category, topic) {

// load in the appropriate section for the category/topic pair given.

}

});

At each stage, the meaning of what started with "a click" changes. Yes, ultimately this leads to some content being swapped in in the Page component, but that behaviour only matters inside the Page component. Inside the menu component, the important part is learning what the user picked as submenu and option, and communicating that up. Similarly, in the Submenu the important part is known which option the user picked. Contrast this to the menu, where it is also important to know which submenu that "pick" happened in. Those are similar, but different, behaviours. Finally in the Option, the only thing we care about is "hey parent: the user clicked us. Do something with that information".

"But this is arduous, why would I need to have a full chain when I know that Menu and Submenu don't care?" Well, for starters, they probably do care, because they'll probably want to style themselves when the user picks an option, such that it's obvious what they picked. It's pretty unusual to see a straight up, pass-along chain of this.props calls, usually a little more happens at each stage.

But what if you genuinely need to do something where the "chain" doesn't matter? For instance, you need to have any component be able to throw "an error" at an error log or notifying component that lives "somewhere" in the app and you don't know (nor care) where? Then we need one of the following two solutions.

Targeted events using the Publish/Subscribe model

The publish/subscribe model for event handling is the system where you have a mechanism to fire off events "at an event monitor", who will then deliver (copies of) that event to anyone who registered as a listener. In Java, this is the "EventListener" interface, in JavaScript's it's basically the document.addEventListener + document.dispatch(new CustomEvent) approach. Things are pretty straight forward, although we need to make sure to never, ever use plain strings for our event names, because hot damn is that asking for bugs once someone starts to refactor the code:

var EventNames = require("eventnames");

var SomeThingSomewhere = React.createClass({

mixins: [

pubsub: require(...)

],

componentWillMount: function() {

if (retrieval of something crucial failed) {

this.pubsub.generate(EventNames.ERROR, {

msg: "something went terribly wrong",

code: 13

});

}

},

render: function() {

...

},

...

});

var ErrorNotifier = React.createClass({

mixins: [

pubsub: require(...)

],

getInitialState: function() {

return { errors: [] };

},

componentWillMount: function() {

pubsub.register(EventNames.ERROR, this.showError);

},

render() {

...

},

showError: function(err) {

this.setState({

errors: this.state.errors.slice().concat([err])

});

}

});

We can send off error messages into "the void" using the publish/subscribe event manager, and have the ErrorNotifier trigger each time an error event comes flying by. The reason we can do this is crucial: when a component has "data that someone might be able to use, but is meaningless to myself" then sending that data off over an event manager is an excellent plan. If, however, the data does have meaning to the component itself, like in the menu system above, then the pub/sub approach is tempting, but arguably taking shortcuts without good justification.

Of course we can take the publish/subscribe model one step further, by removing the need to subscribe...

Events on steroids: the broadcasting approach

In the walkie-talkie method of event management, events are sent into the manager, but everybody gets a copy, no ifs, no buts, the events are simply thrown at you and if you can't do anything with them, then you ignore them, a bit like a bus or taxi dispatcher, when everyone's listening in on the same radio frequency, which is why in the Flux pattern this kind of event manager is called the Dispatcher.

A Dispatcher pattern simplifies life by not needing to explicitly subscribe for specific events, you just see all the events fly by and if you know that you need to do something based on one or more of them, you just "do your job". The downside of course is that there will generally be more events that you don't care about than events that you do, so the Dispatcher pattern is great for applications with lots of independent "data generators" and "consumers", but not so great if you have a well modelled application, where you (as designer) can point at various components and say what they should reasonably care about in terms of blind events.

You promised to circle back, so: what should I go with?

Perhaps not surprisingly, I can't really tell you, at least not with authority. I have my own preferences, but need trumps preference, so choose wisely.

If you're working with React, then depending on where you are in your development cycle, as well as learning curve, many of the topics covered are things you're going to run into, and it's going to make life weird, and you'll need to make decisions on how to proceed based on what you need.

As far as I'm concerned, my preference is to "stick with React" as much as you can: a well modeled centralized component that maintains state, with this.props chaining to propagate and process updates, letting render() take care of keeping the UI in sync with what the user thinks they're doing, dipping sparingly into the publish/subscribe event model when you have to (such as a passive reflector component, like an error notifier that has no "parent" or "child" relationships, it's just a bin to throw data into).

I also prefer to solve problems before they become problems by modeling things in a way that takes advantage of everything it has to offer, which means I'm not the biggest fan of the Dispatcher model, because it feels like when that becomes necessary, an irreparable breakdown of your model has occurred.

I also don't think you should be writing your components in a way that blocks them from doing the very thing you use React for: having a lightning fast, easy to maintain user interface. While I do think you should be saving and syncing your state, I have strong opinions on "update first, then sync" because the user should never feel like they're waiting. The challenge then is error handling after the fact, but that's something you generally want to analyse and solve on a case-by-case basis.

I think you should use state to reflect the component state, no more, no less, and wherever possible, make that overlap with the "full state" that fits your abstract notion of the thing you're modeling; the more you can props-delegate, and the less you need to rely on blind events, the better off your code base is going to be. Not just for you, but also for other developers and, hopefully, contributors.

And before closing, an example: implementing editable elements.

Let's look at something that is typical of the "how do we do this right?" problem: editable forms. And I mean generic forms, so in this case, it's a form that lets you control various aspects of an HTML element.

This sounds simple, and in traditional HTML, sort of is simple: set up a form with fields you can change, tie their events to "your thing"s settings, and then update your thing based on user interaction with the form. In React things have to necessarily happen a little differently, but to the user it should feel the same. Change form -> update element.

Let's start with something simple: the element. I know, React already has pre-made components for HTML elements, but we want a freely transformable and stylable one. In abstract, we want something like this:

element:

attributeset:

- src

- alt

- title

transform:

- translation

- rotation

- scale

- origin

styling:

- opacity

- border

Which, at a first stab, could be the following React component:

var utils = require("handyHelperUtilities");

var Element = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return utils.getDefaultElementDefinition(this.props);

},

render: function() {

var CSS = utils.convertToCSS(this.state);

return (

);

}

});

);

}

});

But, does that make sense? Should this component ever be able to change its internal state? Yes, the abstract model as expressed as, for instance, a database record would certainly treat "changed data" as the same record with new values but the same id, but functionally, the component is just "expressing a bunch of values via the medium of a UI component", so there isn't actually any reason for these values to be "state", as such. Let's try this again, but this time making the Image a "dumb" element, that simply renders what it is given:

var utils = require("handyHelperUtilities");

var Element = React.createClass({

getInitialProps: function() {

return utils.getDefaultElementDefinition(this.props);

},

render: function() {

var CSS = utils.convertToCSS(this.props);

return (

);

}

});

);

}

});

Virtually identical, but this is a drastically different thing: instead of suggesting that the values it expresses is controlled by itself, this is simply a UI component that draws "something" based on the data we pass it when we use it. But we know these values can change, so we need something that does get to manipulate values. We could call that an Editor, but we're also going to use it to show the element without any editorial options, so let's make sure we use a name that describes what we have:

var EditableElement = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return ...?

},

componentWillMount: function() {

...?

},

render: function() {

var flatProperties = utils.flatten(this.state);

return Let's build that out: we want to be able to edit this editable element, so let's also write an editor:

var utils = require(...) = {

...

generateEditorComponents: function (properties, updateCallback) {

return properties.map(name => {

utils.getEditorComponent(name, properties[name], updateCallback);

});

},

getEditorComponent: function(name, value, updateCallback) {

var Controller = utils.getReactComponent(name);

return Now: how do we get these components linked up?

EditableElement -> (Editor, Image)

The simplest solution is to rely on props to just "do the right thing", with updates triggering state changes, which trigger a render() which will consequently just do the right thing some more:

var EditableElement = React.createClass({

...

render: function() {

var flatProperties = utils.flatten(this.state);

flatProperties.onUpdate = this.onUpdate;

return (

{ this.state.editing ? In fact, with this layout, we can even make sure the Editor has a preview of the element we're editing:

var Editor = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

Excellent! The thing to notice here is that the EditableElement holds all the strings: it decides whether to show a plain element, or the editor-wrapped version, and it tells the editor that any changes it makes, it should communicate back, directly, via the onUpdate function call. If an update is sent over, the EditableElement updates its state to reflect this change, and the render chain ensures that everything "downstream" updates accordingly.

Doesn't that mean we're updating too much?

Let's say the Editor has a slider for controlling opacity, and we drag it from 1.0 to 0.5. The Editor calls this.props.onUpdate("opacity", 0.5), which makes the EditableElement call setState({opacity: 0.5}), which calls render(), which sees an update in state, which means React propages the new values to the Editor, which sees an update in its properties and so calls its own render(), which then redraws the UI to match the exact same thing as what we just turned it into. Aren't we wasting time and processing on this? We're just getting the Editor's slider value up into the Element, we don't need a full redraw, do we?

Time to repeat that sentence one more time:

If used correctly, your users will think they are manipulating a UI, when in fact they are manipulating React, which may then update the UI

In redux, this means we did not first change that slider to 0.5, and so we definitely need that redraw, because nothing has changed yet! You're initiating a change-event that React gets, after which updates may happen, but the slider hasn't updated yet. React takes your requested change, kills it off as far as the browser is concerned, and then forwards the "suggestion" in your event to whatever handles value changes. If those changes get rejected, nothing happens. For example, if our element is set to ignore opacity changes, then despite us trying to drag the opacity slider, that slider will not budge, no matter how much we tug on it.

Extended editorial control

We can extend the editor so that it becomes more and more detailed, while sticking with this pattern. For instance, say that in addition to the simple editing, we also want some expert editing: there's some "basic" controls with sliders, and some "expert" controls with input fields:

var SimpleControls = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return utils.generateSimpleEditorComponents(this.props, this.onUpdate);

}

});

var ExpertControls = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return utils.generateExpertEditorComponents(this.props, this.onUpdate);

}

});

var Editor = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

);

},

onUpdate: function(propertyLookup, newValue) {

this.props.onUpdate(propertyLookup, newValue);

}

});

Done. The Editor is still responsible for moving data up to the EditableElement, and the simple vs. expert controls simply tap into the exact same properties. If the parent is rendered with updates, they will "instantly" propagate down.

And that's it...

If you made it all the way to the bottom, I've taken up a lot of your time, so first off: thanks for reading! But more importantly, I hope there was some new information in this post that helps you understand React a little better. And if there's anything in this post that you disagree with, or feel is weirdly explained, or know is outright wrong: let me know! I'm not done learning either!

|

|

Mozilla Security Blog: Changes to the Firefox Bug Bounty Program |

The Bug Bounty Program is an important part of security here at Mozilla. This program has paid out close to 1.6 million dollars to date and we are very happy with the success of it. We have a great community of researchers who have really contributed to the security of Firefox and our other products.

Those of us on the Bug Bounty Committee did an evaluation of the Firefox bug bounty program as it stands and decided it was time for a change.

First, we looked at how much we award for a vulnerability. The amount awarded was increased to $3000 five years ago and it is definitely time for this to be increased again. We have dramatically increased the amount of money that a vulnerability is worth. On top of that, we took a look at how we decided how much we should pay out. Rather than just one amount that can be awarded, we are moving to a variable payout based on the quality of the bug report, the severity of the bug, and how clearly the vulnerability can be exploited.

Finally, we looked into how we decide what vulnerability is worth a bounty award. Historically we would award $3000 for vulnerabilities rated Critical and High. Issues would come up where a vulnerability was interesting but was ultimately rated as Moderate. From now on, we will officially be paying out on Moderate rated vulnerabilities. The amount that is paid out will be determined by the committee, but the general range is $500 to $2000. This doesn’t mean that all Moderate vulnerabilities will be awarded a bounty but some will.

All of these changes can be found on our website here: here

Another exciting announcement to make is the official release of our Firefox Security Bug Bounty Hall of Fame! This page has been up for a while but we haven’t announced it until now. This is a great place to find your name if you are a researcher who has found a vulnerability or if you want to see all the people who have helped make Firefox so secure.

We will be making a Web and Services Bug Bounty Hall of Fame page very soon. Keep an eye out for that!

https://www.mozilla.org/en-US/security/bug-bounty/hall-of-fame/